SMS Pommern

SMS Pommern in 1907

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Pommern |

| Namesake | Pomerania |

| Builder | AG Vulcan, Stettin |

| Laid down | 22 March 1904 |

| Launched | 2 December 1905 |

| Commissioned | 6 August 1907 |

| Fate | Sunk by British destroyers at the Battle of Jutland, 1 June 1916 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 127.6 m (418 ft 8 in) |

| Beam | 22.2 m (72 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 7.7 m (25 ft 3 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 5,830 nmi (10,800 km; 6,710 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Pommern[a] was one of five Template:Sclass- pre-dreadnought battleships built for the Kaiserliche Marine between 1904 and 1906. Named after the Prussian province of Pomerania, she was built at the AG Vulcan yard at Stettin, Germany (now Szczecin, Poland), where she was laid down on 22 March 1904 and launched on 2 December 1905. She was commissioned into the navy on 6 August 1907. The ship was armed with a battery of four 28 cm (11 in) guns and had a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). The ships of her class were already outdated by the time they entered the service, being inferior in size, armor, firepower, and speed to the revolutionary new battleship HMS Dreadnought.

After commissioning, Pommern was assigned to the II Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet, where she served throughout her peacetime career and the first two years of World War I. Before the war, the fleet was primarily occupied with cruises and extensive training exercises, developing strategic concepts for use in a future conflict. At the start of the war, Pommern and the rest of the II Battle Squadron were tasked with supporting the defenses of the German Bight, and were stationed at the mouth of the Elbe. They also participated in several fruitless sorties into the North Sea in attempts to lure out and destroy a portion of the British Grand Fleet.

These offensive operations culminated in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916. She and her sisters briefly engaged the British battlecruisers commanded by David Beatty late on the first day, and Pommern was hit once by a 12 in (30.5 cm) shell from the battlecruiser HMS Indomitable. During the confused night actions in the early hours of 1 June, she was hit by one, or possibly two, torpedoes from the British destroyer HMS Onslaught, which detonated one of Pommern's 17-centimeter (6.7 in) gun magazines. The resulting explosion broke the ship in half and killed the entire crew. Pommern was the only battleship of either side sunk during the battle.

Design

The passage of the Second Naval Law in 1900 under the direction of Vizeadmiral (VAdm—Vice Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz secured funding for the construction of twenty new battleships over the next seventeen years. The first group, the five Template:Sclass-s, were laid down in the early 1900s, and shortly thereafter work began on a follow-on design, which became the Template:Sclass-. The Deutschland-class ships were broadly similar to the Braunschweigs, featuring incremental improvements in armor protection. They also abandoned the gun turrets for the secondary battery guns, moving them back to traditional casemates to save weight.[1][2] The British battleship HMS Dreadnought—armed with ten 12-inch (30.5 cm) guns—was commissioned in December 1906.[3] Dreadnought's revolutionary design rendered every capital ship of the German navy obsolete, including Pommern.[4]

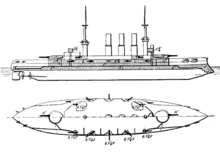

Pommern was 127.6 m (418 ft 8 in) long overall, with a beam of 22.2 m (72 ft 10 in), and a draft of 8.21 m (26 ft 11 in). She displaced 14,218 metric tons (13,993 long tons) at full loading. The ship was equipped with two heavy military masts and triple expansion engines that were rated at 17,453 indicated horsepower (13,015 kW). She had a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), though she significantly exceeded that speed on trials, being the fastest member of the class. Steam was provided by twelve Schulz-Thornycroft boilers; three funnels vented smoke from burning coal in the boilers. The ship had a fuel capacity of up to 1,540 metric tons (1,520 long tons; 1,700 short tons) of coal. In addition to being the fastest ship of her class, Pommern was the most fuel efficient. At a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), she could steam for 5,830 nautical miles (10,800 km; 6,710 mi).[5] Her crew numbered 35 officers and 708 enlisted men.[6]

Pommern's primary armament consisted of four 28 cm (11 in) SK L/40 guns in two twin turrets.[b] Her secondary battery was fourteen 17 cm (6.7 in) SK L/40 guns mounted in casemates and twenty 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 naval guns in pivot mounts. The ship was also armed with six 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, all submerged in the hull. One was in the bow, one in the stern, and four on the broadside. Krupp cemented armor protected the ship. Her armored belt was 240 millimeters (9.4 in) thick in the central portion, where it protected her magazines and machinery spaces, while thinner plating covered the ends of the hull. Her main-deck armor was 40 mm (1.6 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 280 mm (11 in) of armor plating.[8][9]

Service history

Pommern was ordered under the contract name "O", as a new addition to the fleet's numerical strength.[10] She was laid down on 22 March 1904 at the AG Vulcan dockyard in Stettin.[1] She was originally scheduled to be launched on 19 November 1905, but the water level in the harbor was too low. As a result, the ship could not be launched until 2 December.[11] The Oberpräsident (High Commissioner) of Pommern, Helmuth von Maltzahn, gave the launching speech.[10] In July 1907 Pommern was transferred to Kiel where she had her main battery of four 28 cm (11 in) guns installed.[11] She was commissioned for trials on 6 August; during her speed run, she reached 19.26 knots (35.67 km/h; 22.16 mph), which made her the fastest pre-dreadnought battleship in the world.[12]

Pommern was assigned to the II Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet alongside her sisters, replacing the battleship Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm, though she was not fully ready for active duty until 11 November.[13] Pommern participated in fleet maneuvers in February 1908 in the Baltic Sea and more fleet training off Helgoland in May–June. In July, Pommern and the rest of the fleet sailed into the Atlantic Ocean to conduct a major training cruise. Prince Heinrich had pressed for such a cruise the previous year, arguing that it would prepare the fleet for overseas operations and would break up the monotony of training in German waters, though tensions with Britain over the developing Anglo-German naval arms race were high. The fleet departed Kiel on 17 July, passed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to the North Sea, and continued on to the Atlantic. The fleet returned to Germany on 13 August, and the annual autumn maneuvers followed from 27 August to 12 September.Later that year, the fleet toured coastal German cities as part of an effort to increase public support for naval expenditures.[14]

The next year—1909—followed much the same pattern. Another cruise into the Atlantic was conducted from 7 July to 1 August, and while on the way back to Germany, the High Seas Fleet was received by the British Royal Navy in Spithead.[15] Late in the year, VAdm Henning von Holtzendorff became the commander of the High Seas Fleet. His tenure as fleet commander was marked by strategic experimentation, owing to the increased threat the latest underwater weapons posed, and because the new Template:Sclass-s were too wide to pass through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. Accordingly, the fleet was transferred from Kiel to Wilhelmshaven on 1 April 1910. In May 1910, the fleet conducted training maneuvers in the Kattegat, between Norway and Denmark. These were in accordance with Holtzendorff's strategy, which envisioned drawing the Royal Navy into the narrow waters in the Kattegat. The annual summer cruise went to Norway, and was followed by fleet training, during which another fleet review was held in Danzig on 29 August. A training cruise into the Baltic followed at the end of the year.[16]

In March 1911, the fleet conducted exercises in the Skagerrak and Kattegat. Pommern and the rest of the fleet received British and American naval squadrons in Kiel in June and July. The year's autumn maneuvers were confined to the Baltic and the Kattegat. Another fleet review was held during the exercises for a visiting Austro-Hungarian delegation that included Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli. In mid-1912, due to the Agadir Crisis, the summer cruise only went into the Baltic to avoid exposing the fleet during the period of heightened tension with Britain and France.[17] Pommern took part in several celebrations commemorating the fiftieth anniversaries of events from the Second Schleswig War. The first, on 17 March, took place at Swinemünde, on the anniversary of the Battle of Jasmund participated in ceremonies at Sonderburg on 2 May 1914 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Dybbøl.[13]

World War I

In July 1914, about two weeks after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Pommern was with the High Seas Fleet during its annual summer cruise to Norway. As a result of rising international tensions, the cruise was cut short and the German fleet was back in Wilhelmshaven by 29 July.[18] At midnight on 4 August, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany for violating Belgium's neutrality.[19] Pommern remained with the High Seas Fleet throughout the first two years of the naval war.[11] At the outbreak of war, the German command deployed the II Squadron in the German Bight to defend Germany's coast from a major attack from the Royal Navy that the Germans presumed was imminent. Pommern and her squadron mates were stationed in the mouth of the Elbe to support the vessels on patrol duty in the Bight.[20]

Once it became clear that the British would not attack the High Seas Fleet, the Germans began a series of operations designed to lure out part of the numerically superior British Grand Fleet and destroy it.[21] The German navy was aiming to force a decisive battle in the southern portion of the North Sea after achieving a rough equality of forces.[22] Pommern and the rest of the II Battle Squadron then rejoined the High Seas Fleet as part of the battleship support for the battlecruisers in the I Scouting Group that bombarded Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby on 15–16 December 1914.[23] The main fleet acted as distant support for Konteradmiral (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Franz von Hipper's battlecruiser squadron while it raided the coastal towns. On the evening of 15 December, the fleet came to within 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) of an isolated squadron of six British battleships. However, skirmishes between the rival destroyer screens in the darkness convinced the German fleet commander, VAdm Friedrich von Ingenohl, that the entire Grand Fleet was deployed before him. Under orders from Wilhelm II to avoid battle if victory was not certain, von Ingenohl broke off the engagement and turned the battlefleet back towards Germany.[24]

Two fruitless fleet advances followed on 17–18 and 21–23 April 1915. A third took place on 17–18 May, and a fourth occurred on 23–24 October.[23] On 24–25 April 1916, Pommern and her sisters joined the dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet to support the battlecruisers, which were again tasked with conducting a raid of the English coast.[25] While en route to the target, a mine damaged the battlecruiser Seydlitz. She was detached to return home, and the rest of the ships continued with the mission. Due to poor visibility, the battlecruisers conducted a brief bombardment of the ports of Yarmouth and Lowestoft. The operation was quickly called off, preventing the British fleet from being able to intervene.[26]

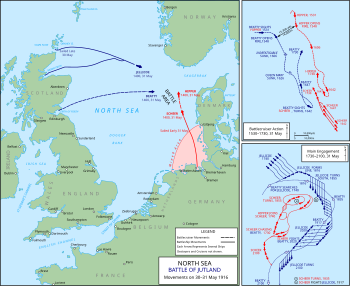

Battle of Jutland

VAdm Reinhard Scheer, the new commander of the High Seas Fleet, immediately planned another foray into the North Sea, but the damage to Seydlitz delayed the operation until the end of May.[27] On 31 May, at 02:00 CET, Hipper's battlecruisers steamed out towards the Skagerrak, followed by the rest of the High Seas Fleet an hour and a half later.[28] Pommern remained assigned to the II Battle Squadron, which was positioned at the rear of the German line and under the command of Kadm Franz Mauve.[29] During the "Run to the North," Scheer ordered the fleet to pursue the British V Battle Squadron at top speed. The slower Deutschland-class ships could not keep up with the faster dreadnoughts and quickly fell behind.[30] By 19:30, the Grand Fleet had arrived on the scene and confronted Scheer with significant numerical superiority.[31] The German fleet was severely hampered by the presence of the slower Deutschland-class ships; if Scheer ordered an immediate turn towards Germany, he would have to sacrifice the slower ships to make good his escape.[32]

Scheer decided to reverse the course of the fleet with the Gefechtskehrtwendung, a maneuver that required every unit in the German line to turn 180° simultaneously.[33] As a result of their having fallen behind, the ships of the II Battle Squadron could not conform to the new course following the turn,[34] so Pommern and the other five ships of the squadron were located on the disengaged side of the German line. Mauve considered moving his ships to the rear of the line, astern of the III Battle Squadron dreadnoughts, but decided against it when he realized the movement would interfere with the maneuvering of Hipper's battlecruisers. Instead, he attempted to place his ships at the head of the line.[35]

Later in the evening of the first day of the battle, the hard-pressed battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group were being pursued by their British opponents. Pommern and the other so-called "five-minute ships" came to their aid by steaming in between the opposing battlecruiser squadrons.[36][c] Pommern could not make out a target in the darkness, but several of her sisters could, though their shooting was ineffective.[37] The British battlecruisers scored several hits on the German ships, including one on Pommern by a 12-inch (30.5 cm) shell fired by Indomitable,[38] forcing her to haul out of line. Mauve ordered an 8-point turn to the south to disengage from the British, and they did not follow.[37]

At 3:10 on the morning of 1 June, Pommern was torpedoed by the British destroyer Onslaught. At least one torpedo, and possibly a second, struck the ship, detonating one of the 17 cm ammunition magazines.[39] A tremendous explosion broke the ship in half. The stern capsized and remained afloat for at least 20 minutes with her propellers jutting into the air.[40] Hannover, the ship directly astern of Pommern, was forced to haul out of line to avoid the wreck. Pommern's entire crew of 839 officers and enlisted men were killed when the ship sank.[41] She was the only battleship, pre-dreadnought or dreadnought, in either fleet to be sunk at Jutland;[42] her loss, coupled with the vulnerabilities of the surviving pre-dreadnoughts, prompted Scheer to leave them behind during the sortie of 18–19 August 1916.[43] The ship's bow ornament, which had been removed at the outbreak of war in July 1914, is preserved at the Laboe Naval Memorial.[13]

Footnotes

Notes

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick loading, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 caliber, meaning that the gun is 40 times as long as it is in diameter.[7]

- ^ The men of the German navy referred to ships as "five-minute ships" because that was the length of time they were expected to survive if confronted by a dreadnought.[28]

Citations

- ^ a b Staff, p. 5.

- ^ Hore, p. 69.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Herwig, p. 57.

- ^ Gröner, p. 21.

- ^ Gröner, p. 20.

- ^ Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Staff, p. 6.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 7, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Staff, p. 12.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 7, pp. 237–238.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 7, p. 238.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 2, p. 238.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 2, pp. 235, 238.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 2, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 2, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Staff, p. 11.

- ^ Herwig, p. 144.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 7, p. 249.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 27.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 136.

- ^ a b Staff, p. 14.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Staff, p. 10.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 58.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 62.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 286.

- ^ London, p. 73.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 150.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 154.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 155.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 195.

- ^ a b London, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Campbell, p. 254.

- ^ Staff, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Campbell, p. 305.

- ^ Staff, p. 13.

- ^ Campbell, p. 338.

- ^ Halpern, p. 330.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7. OCLC 57447525.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Band 2) [The German Warships (Volume 2)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Band 7) [The German Warships (Volume 7)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8364-9743-5.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- London, Charles (2000). Jutland 1916: Clash of the Dreadnoughts. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-992-8.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918 (1). Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan (2014). "Last of the Line: The German Battleships of the Braunschweig and Deutschland Classes". Warship 2014. London: Conway Maritime Press: 49–69. ISBN 978-1591149231.