Screw (magazine)

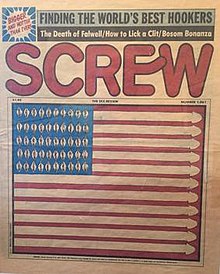

The cover of issue #1,061 (July 3, 1989), which replaced the stars and stripes of the U.S. flag with female and male genitals. Designed by Mikhail Armalinsky. | |

| Editor | Bruce David (1970s) |

|---|---|

| Categories | Pornographic men's |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Circulation | 140,000 |

| Publisher | Phil Autelitano (2018–) Kevin Hein (2004–2007) Al Goldstein/Milky Way Productions (1968–2003) |

| Founder | Al Goldstein and Jim Buckley |

| First issue | 1968 |

| Company | AMG, LLC |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City (1968–2007) Miami, Florida (2020–present) |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

Screw is a pornographic online magazine published in the United States aimed at heterosexual men; it was originally published as a weekly tabloid newspaper.

The publication, which was described as "raunchy, obnoxious, usually disgusting, and sometimes political",[1] was a pioneer in bringing hardcore pornography into the American mainstream during the late 1960s and early 1970s.[2][3][4] Founder Al Goldstein won a series of nationally significant court cases addressing obscenity.[5] At its peak, Screw sold 140,000 copies a week.[6][7]

Publication history

[edit]In November 1968 in New York, Al Goldstein and his partner Jim Buckley, investing $175 each, founded Screw as a weekly underground newspaper.[8][2] An an initial price of 25¢, a statement on the cover offered "Jerk-Off Entertainment for Men".[9]

Beginning in 1969, Screw co-founder Jim Buckley founded Screw's "sister" tabloid Gay,[10] edited by Screw columnists Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke. Contributors to Gay included Dick Leitsch, Randy Wicker, Lilli Vincenz, Peter Fisher, John Paul Hudson, Arthur Bell, Vito Russo, and George Weinberg. Gay reached "a broad audience and went on to become the most profitable LGBT newspaper in the U.S.;" it continued until early 1974.[11]

In 1973, Screw published nude photos of former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, which led to scandal — and issue sales of more than a half-million copies.[2][12] (Nude photos of Onassis had previously appeared in the Italian softcore magazine Playmen and later were published by the American hardcore magazine Hustler.)[13]

Goldstein tried, unsuccessfully, to expand Screw's reach beyond New York City. In 1976–1977 National Screw was published, only lasting nine issues. The June 1977 issue of the magazine contained, according to its cover, a new story by William Burroughs and an interview with Allen Ginsberg.[14] Other issues contained original adult comic strip work from cartooning legends Wally Wood, Guido Crepax, and Will Eisner.[15]

In 1979–1980, Goldstein's company, Milky Way Productions, published Screw West out of an office in Hollywood, California. According to an advertisement, it was intended to answer such questions as, "Where can I get laid in San Francisco? What's the best swinger's club in Los Angeles? How do I find all those out-of-the-way Pacific Coast nude beaches? And what are those bawdy brothels outside Las Vegas really like?" Screw West is known to have published 54 issues.[16]

One of Goldstein's best friends was Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler magazine, founded seven years after Screw. Goldstein claimed that Hustler stole its format from Screw, but that he was not angry. According to Goldstein, Flynt succeeded in creating a national publication, at which he had failed.[17]

Screw folded in 2003, unable to make payroll;[18] only 600 copies were sold of the last issue.[19] Goldstein's Milky Way Productions, which published Screw and Midnight Blue, entered bankruptcy in 2004, having lost sales and subscribers as a result of the proliferation of internet pornography, abetted by Goldstein's financial mismanagement.[20]

2004 relaunch

[edit]In 2004 the Screw periodical was restarted by former employees led by Kevin Hein, with writer Mike Edison coming onboard as the new editor. (Edison had started writing as a freelancer for Screw almost two decades earlier.) In late 2006 Edison announced that he was leaving the editor-in-chief position. Soon after, in 2007, Screw ceased physical publication as the title neared, but did not reach, its 2,000th issue.[21]

Original founder Al Goldstein died in 2013.[2][4]

2019–2020 relaunch

[edit]In 2019, Screw returned as an adult, subscription-based television channel ("SCREW TV") on Roku, developed and produced by longtime Goldstein friend and associate Phil Autelitano.[22]

On November 4, 2020, the 52nd anniversary of its initial launch, Screw resumed publishing in digital-only format, published by Autelitano (as "Phil Italiano") and Autelitano Media Group of Miami, Florida.[23]

Contents

[edit]Screw features reviews of porn movies, peep shows, erotic massage parlors, brothels, escorts, and other offerings of the adult entertainment industry. Such items are interspersed with sexual news, book reviews of sexual books, and hardcore "gynecological" pictorials. The original paper regularly ran, without permission, photos and drawings of celebrities.

According to author Will Sloan:

Goldstein was the first journalist to seriously review porn films. Had he not written a rave review of a low-budget film called Deep Throat ('I was never so moved by any theatrical performance since stuttering through my own bar mitzvah'), it would never have become a hit at New York's World Theater, would never have been targeted by the vice squad, would never have spawned a First Amendment cause célèbre, and might not have led to the modern porn industry.[19]

Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke's column "The Homosexual Citizen", which launched in 1968, was the first LGBT-interest column in a non-LGBT publication.[24] As a result of this column, Nichols and Clarke became known as "The most famous gay couple in America."[citation needed]

On May 2, 1969, Screw published the first reference in print to J. Edgar Hoover's sexuality, entitled "Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?"[25][1][26][27] A few issues later, Screw became the first publication to print the word "homophobia" (a term coined by George Weinberg).[28] The word appeared in an article written for the May 23, 1969, issue, in which the word was used to refer to heterosexual men's fear that others might think they are gay.[29]

In December 1970, New York City music teacher Pat Bond placed an ad in Screw that led Bond to connect with Fran Nowve, and for the two of them to form The Eulenspiegel Society, the first BDSM organization founded in the United States.[30]

Screw's most successful issue, published in 1973, contained unauthorized photos of Jacqueline Kennedy nude.[31]

Stripper and erotic performance artist Honeysuckle Divine wrote a column, "Diary of a Dirty Broad", for Screw for several years in the mid-1970s.[32] Divine's specialty was inserting objects such as pickles in her vagina, shooting out many of them. She put the pickles in baggies and sold them to patrons. Goldstein said that her act "was unbelievably disgusting, so naturally, we made her our symbol."[19] Divine was the only female associated with Screw over any period of time;[citation needed] she also appeared in the 1975 feature production SOS: Screw on the Screen.[33]

Legal battles

[edit]In 1974, publishers Goldstein and Buckley were charged with 12 counts of obscenity in a federal court in Kansas. (Goldstein believed that the case began as a result of Screw's May 1969 article, "Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?")[1] The case dragged on for three years through two trials and was finally settled when Goldstein agreed to pay a $30,000 fine.[34]

In 1977, Alabama governor George Wallace sued Screw for $5 million for publishing the claim that he had learned to perform sexual acts from reading the magazine. The two parties settled for $12,500, and Screw agreed to print an apology.[35]

In 1978, Screw set in motion a precedent-setting case that established fair-use protections for publication of registered trademarks in sexually explicit parodies in the United States.[36] Known as Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions, the case stemmed from an illustration in Screw depicting a figure resembling the Pillsbury Dough Boy in various lewd sexual acts, including fellatio and sexual intercourse. The parody also featured Pillsbury's barrelhead trademark and two lines from the refrain of a two-stanza song entitled "The Pillsbury Baking Song". The illustration was published in the February 20, 1978, issue of Screw. The Pillsbury Company filed an initial complaint several weeks after the original publication of the cartoon, contending that the manner in which the magazine presented the picture implied that Pillsbury placed it in the magazine as an advertisement. Pillsbury alleged several counts of copyright infringement, federal statutory, common law trademark infringement, violations of the Georgia Uniform Deceptive Trade Practices Act and of the Georgia "anti-dilution" statute, and several counts of tortious tarnishment of its marks, trade characters, and jingle. The judge presiding in the case issued a temporary injunction against Screw on April 21, 1978, which the defendant disobeyed.[37] Ultimately, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia held that the pictures were editorial or social commentary and, thus, protected under fair use.[38]

Contributors

[edit]Larry Brill and Les Waldstein were the original designers for Screw, having earlier designed Famous Monsters of Filmland and other Jim Warren publications in the late 1960s. Brill and Waldstein later went on to become the publishers of The Monster Times. Steven Heller later served as the paper's art director, before moving on to The New York Times.

Artist René Moncada became a major contributor to Screw beginning in the late 1960s, which provided an outlet for the artist's early erotic illustrations, and a forum for his later anti-censorship diatribes.[39]

A number of underground and alternative cartoonists got their start doing illustrations and comics for Screw, including Bill Griffith, Milton Knight, Leslie Cabarga, Drew Friedman,[40] Tony Millionaire, Eric Drooker, Kaz, Danny Hellman, Glenn Head, Bob Fingerman, Michael Kupperman, and Molly Crabapple. Spain Rodriguez contributed cover art to more than a dozen issues of Screw from 1976 to 1998. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Paul Kirchner did several dozen covers for the publication. "Good girl" artist Bill Ward also did a number of covers for Screw.[41]

Writer Josh Alan Friedman's first published work was for Screw in the late 1970s. He continued to write for the magazine for several years, eventually holding the position of Senior Editor through 1982. He covered the Times Square beat for Screw during a perilous time when few, if any writers, ventured there. He also worked as a producer on Screw's cable television show, Midnight Blue.

David Aaron Clark edited Screw for five years in the early 1990s.

Screw in other media

[edit]Movies and television

[edit]In 1973, "Screw Magazine present[ed]" It Happened in Hollywood, a pornographic movie produced by Jim Buckley. At the Second Annual New York Erotic Film Festival it won awards for Best Picture, Best Female Performance, and Best Supporting Actor.[42]

In 1974 Goldstein began Screw Magazine of the Air, soon renamed Midnight Blue, a thrice-weekly hour-long adult-oriented public-access television program that ran for nearly 30 years on Manhattan Cable's Channel J.[43][4]

SOS: Screw on the Screen appearing in 1975, was a stridently unsexy attempt at a cinematic newsmagazine that included a lot of goofy comedy, a gay scene, and several minutes of Goldstein ranting about America's sexual hypocrisy. Also appearing was Honeysuckle Divine (who often appeared in Screw).

The Screw Store

[edit]The May 17, 1976, issue ran an ad for the "Screw Store", which offered dildos, including a "Bicentennial Dildo", vibrating Ben wa eggs, and a vibrating cock ring.[44] Selling dildos brought one of Goldstein's many arrests.[19][45]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Davis, Marc (November 18, 2013). "The Screw-y, Filthy World of Al Goldstein". Jewniverse. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Newman, Andy (December 19, 2013). "Al Goldstein, a Publisher Who Took the Romance Out of Sex, Dies at 77". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ Cavaliere, Victoria (December 19, 2013). "Al Goldstein, pornography pioneer who claimed free speech, dies". Reuters. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Screw magazine publisher Al Goldstein dies aged 77". The Guardian. Associated Press. December 19, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ Frumkes, Roy (December 21, 2008). "FIR '08 Stocking Stuffer". Films in Review. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ^ West, Ashley. "Remembering Al Goldstein: A Happy Jew," The Rialto Report (January 5, 2014). Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Whitby, Bob (February 22, 2001). "Screwed". Broward/Palm Beach New Times. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "Defunct or Suspended Magazines, 2003". The Association of Magazine Media. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ "Screw Magazine Tumblr account". www.tumblr.com. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "Advertisement for Gay from the pages of Screw (March 11, 1974)". Tumblr. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Shockley, Jay (December 2022). "GAY Newspaper Offices". NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

- ^ "SCREW PUBLISHED NUDE PAPARAZZI PHOTOGRAPHS OF FORMER FIRST LADY JACQUELINE KENNEDY ONASSIS". Avenue Magazine. May–June 2023.

- ^ Bianchi, Martín (September 11, 2023). "Jackie Kennedy and the billion dollar nude: 50 years since the first case of 'revenge porn'". El País English.

- ^ "Vintage Adult Magazine Covers". Vintageadultmagazinecovers.tumblr.com. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ "Library Catalog – National Screw". Cornell University. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "Library Catalog – Screw West". California State University. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "Goldstein on Flynt, Flynt on Goldstein" on YouTube

- ^ Nathan Thornburgh, "82 Minutes with Al Goldstein", New York [magazine], December 10, 2010; retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Sloan, Will (December 20, 2013). "Al Goldstein: The Anti-Hef". Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Newman, Andy (August 12, 2004). "68 and Sleeping on Floor, Ex-Publisher Seeks Work". The New York Times. Retrieved December 23, 2013.; Al Goldstein and Josh Alan Friedman, I, Goldstein. My Screwed Life

- ^ "The New Screw Review". New York Press. March 2, 2005. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ Walker, Reggie (June 17, 2019). "SCREW TV Brings Storied Magazine to Roku". XBIZ. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Parkman, Dave (September 18, 2020). "Miami Group to Relaunch Legacy 'Screw' Magazine". XBIZ. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Byrnes, Ronald (August 6, 1972). "The 'gay' world in sunshine and in shadow". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. p. 62. Retrieved July 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?". Screw. Vol. 1, no. 11. May 2, 1969.

- ^ "Screw : The Sex Review". Specific Object. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Edison, Mike (2011). Dirty! Dirty! Dirty!: Of —Playboys, Pigs, and Penthouse Paupers—An American Tale of Sex and Wonder. Soft Skull Press. ISBN 9781593764678. Retrieved November 21, 2014. ISBN 1593762844

- ^ Grimes, William (March 22, 2017). "George Weinberg Dies at 86; Coined 'Homophobia' After Seeing Fear of Gays". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M. (April 2004). "Beyond 'Homophobia': Thinking About Sexual Prejudice and Stigma in the Twenty-First Century" (PDF). Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 1 (2): 6–24. doi:10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6. S2CID 145788359.

- ^ Weiss, Margot (December 20, 2011). Techniques of Pleasure: BDSM and the Circuits of Sexuality. Duke University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8223-5159-7.

- ^ McShane, Larry. "Al Goldstein, Screw magazine founder and lover of hard-core porn, dies in Brooklyn at 77," New York Daily News (Dec. 19, 2013).

- ^ "Diary of a Dirty Broad". Screw. March 11, 1974. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ SOS: Screw on the Screen at IMDb

- ^ "Goldstein Pays $30,000, Ending Obscenity Trial". The New York Times. March 16, 1978.

- ^ UPI (April 13, 1977). "Wallace Settles with Screw". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ Lim, Eugene (2012). "Of Chew Toys and Designer Handbags: A Critical Analysis of the "Parody" Exception under the U.S. Trademark Dilution Revision Act". Campbell Law Review.

- ^ O'Kelley, William (December 24, 1981). "The Pillsbury Company v. Milky Way Productions, Inc. et al" (PDF). LexisNexis. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Greenstone, Richard. "Protection of Obscene Parody as Fair Use". Richard J. Greenstone Attorneys & Counselors At Law. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "An Apple A Lay". Screw. New York, NY: Goldstein Publications. April 11, 1983. p. 14.

- ^ Kelly, John. "Drew Friedman". The Comics Journal #151 July 1992.

- ^ Ward, Bill. "Cover" Screw #1305 (March 7, 1994) New York: Milky Way Productions.

- ^ "Screw Film Sweeps Awards", Screw (March 26, 1973).

- ^ Bedell Smith, Sally (March 5, 1984). "Channel J Pornography is Cause of Lockout Law". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "May 17, 1976". Screw Magazine. Tumblr. April 20, 2014. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ Friedman, Josh Alan. "Al Goldstein's Personal Ephemera". Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- Pornographic men's magazines

- Defunct magazines published in the United States

- Magazines established in 1968

- Magazines disestablished in 2003

- Magazines published in New York City

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- Pornographic magazines published in the United States

- Weekly magazines published in the United States