Russian invasion of Ukraine

| Russian invasion of Ukraine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Ukrainian War (outline) | |||||||

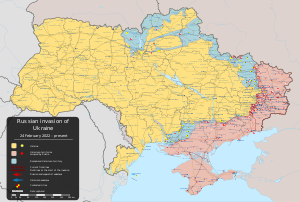

Map of Ukraine as of 1 December 2024[update] (details): Continuously controlled by Ukraine

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Order of battle | Order of battle | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Pre-invasion at border: 169,000–190,000[e][5][6][7] Pre-invasion total: 900,000 military[8] 554,000 paramilitary[8] In February 2023: 300,000+ active personnel in Ukraine[9] In June 2024: 700,000 active personnel in the area[10] |

Pre-invasion total: 196,600 military[11] 102,000 paramilitary[11] July 2022 total: up to 700,000[12] September 2023 total: over 800,000[13] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

"ARMADURA Z29 HELMET ARMOR Z29" by OSCAR CREATIVO | |||||||

|

| |||||||

On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which started in 2014. The invasion, the largest and deadliest conflict in Europe since World War II,[14][15][16] has caused hundreds of thousands of military casualties and tens of thousands of Ukrainian civilian casualties. As of 2024, Russian troops occupy about 20% of Ukraine. From a population of 41 million, about 8 million Ukrainians had been internally displaced and more than 8.2 million had fled the country by April 2023, creating Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II.

In late 2021, Russia massed troops near Ukraine's borders and issued demands including a ban on Ukraine ever joining the NATO military alliance. After repeatedly denying having plans to attack Ukraine, on 24 February 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin announced a "special military operation", saying that it was to support the Russian-backed breakaway republics of Donetsk and Luhansk, whose paramilitary forces had been fighting Ukraine in the Donbas conflict since 2014. Putin espoused irredentist and neo-imperialist views challenging Ukraine's legitimacy as a state, falsely claimed that Ukraine was governed by neo-Nazis persecuting the Russian minority, and said that Russia's goal was to "demilitarize and denazify" Ukraine. Russian air strikes and a ground invasion were launched on a northern front from Belarus towards the capital Kyiv, a southern front from Crimea, and an eastern front from the Donbas and towards Kharkiv. Ukraine enacted martial law, ordered a general mobilization and severed diplomatic relations with Russia.

Russian troops retreated from the north and the outskirts of Kyiv by April 2022, after encountering stiff resistance and logistical challenges. The Bucha massacre was uncovered after their withdrawal. In the southeast, Russia launched an offensive in the Donbas and captured Mariupol after a destructive siege. Russia continued to bomb military and civilian targets far from the front, and struck the energy grid through the winter months. In late 2022, Ukraine launched successful counteroffensives in the south and east, liberating most of Kharkiv province. Soon after, Russia announced the illegal annexation of four partly-occupied provinces. In November, Ukraine liberated Kherson. In June 2023, Ukraine launched another counteroffensive in the southeast, but made few gains. After small but steady Russian advances in the east in the first half of 2024, Ukraine launched a cross-border offensive into Russia's Kursk Oblast in August of that year. The United Nations Human Rights Office reports that Russia is committing severe human rights violations in occupied Ukraine.

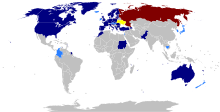

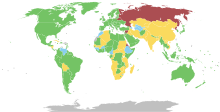

The invasion was met with widespread international condemnation. The United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution condemning the invasion and demanding a full Russian withdrawal. The International Court of Justice ordered Russia to halt military operations, and the Council of Europe expelled Russia. Many countries imposed sanctions on Russia and its ally Belarus, and provided humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine. The Baltic states and Poland declared Russia a terrorist state. Protests occurred around the world, with anti-war protesters in Russia being met by mass arrests and greater media censorship. The Russian attacks on civilians have led to allegations of genocide.[17][18][19][20] War-related disruption to Ukrainian agriculture and shipping contributed to a world food crisis, while war-related environmental damage has been described as ecocide. The International Criminal Court (ICC) opened an investigation into crimes against humanity, war crimes, abduction of Ukrainian children, and genocide against Ukrainians. The ICC issued arrest warrants for Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, and for four Russian military officials.

Background

Post-Soviet relations

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the newly independent states of the Russian Federation and Ukraine maintained cordial relations. In return for security guarantees, Ukraine signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1994, agreeing to dismantle the nuclear weapons the former USSR had left in Ukraine.[21] At that time, Russia, the UK, and the USA agreed in the Budapest Memorandum to uphold Ukraine's territorial integrity.[22] In 1999, Russia signed the Charter for European Security, affirming the right of each state "to choose or change its security arrangements" and to join alliances.[23] In 2002, Putin said that Ukraine's relations with NATO were "a matter for those two partners".[24]

Russian forces invaded Georgia in August 2008 and took control of the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, demonstrating Russia's willingness to use military force to attain its political objectives.[25] The United States "was accused of appeasement and naivete" in their reaction to the invasion.[26]

Ukrainian revolution, Russian intervention in Crimea and Donbas

In 2013, Ukraine's parliament overwhelmingly approved finalising an association agreement with the European Union (EU).[27] Russia had put pressure on Ukraine to reject it.[28] Kremlin adviser Sergei Glazyev warned in September 2013 that if Ukraine signed the EU agreement, Russia would no longer acknowledge Ukraine's borders.[29] In November, Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych suddenly withdrew from signing the agreement,[30] choosing closer ties to the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union instead. This coerced withdrawal triggered a wave of protests known as Euromaidan, culminating in the Revolution of Dignity in February 2014. Yanukovych fled and was removed from power by parliament, ending up in Russia.

Russian soldiers with no insignia occupied the Ukrainian territory of Crimea, and seized the Crimean Parliament.[31] Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014, after a widely disputed referendum held under occupation. Pro-Russian unrest immediately followed in the Ukrainian cities of Donetsk and Luhansk. The war in Donbas began in April 2014 when armed Russian-backed separatists seized Ukrainian government buildings and proclaimed the independent Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic.[32][33] Russian troops were directly involved in these conflicts.[34]

The annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas sparked a wave of Russian nationalism. Analyst Vladimir Socor called Putin's 2014 speech following the annexation a "manifesto of Greater-Russia irredentism".[35] Putin began referring to "Novorossiya" (New Russia), a former Russian imperial territory that covered much of southern Ukraine.[36] Russian-backed forces were influenced by Russian neo-imperialism and sought to create a new Novorossiya.[37][38] Putin referred to the Kosovo independence precedent and NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as a justification for the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas,[39][40][41][42] while historians note the similarities with Nazi Germany's Anschluss of Austria.[43][44]

Because of Russia's occupation of Crimea and its invasion of the Donbas, Ukraine's parliament voted in December 2014 to remove the neutrality clause from the Constitution and to seek Ukraine's membership in NATO.[45][46] However, it was impossible for Ukraine to join NATO at the time, as any applicant country must have no "unresolved external territorial disputes".[47] In 2016, President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, said that it would take 20–25 years for Ukraine to join the EU and NATO.[48]

The Minsk agreements, signed in September 2014 and February 2015, aimed to resolve the conflict, but ceasefires and further negotiations repeatedly failed.[50]

Economic aspects

In August 2012, the Ukrainian government of Mykola Azarov, who, like the then Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, maintained good relations with the Russian leadership, commissioned a consortium including Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, OMV Romania and the Ukrainian state-owned NAK Nadra Ukrainy to extract oil and natural gas in the Ukrainian part of the Black Sea.[51][52] In 2013, Italy's largest oil and gas producer, Eni, was granted a license to extract oil and gas on the east coast of Crimea. In 2014, it was reported that if Crimea were annexed, the production licenses could be reassigned and previous license holders would find themselves in a legal grey area.[52]

Economic interests were also a motive for Russia's attack on Ukraine and its annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts. Lithium deposits in the Donbas and Ukraine's grain wealth would mean a "monopoly on the world market" for Russia if it took over Ukraine.[53] In 2022, Russian General Vladimir Ovchinsky confirmed that the "Russian special operation" was aimed at seizing Ukrainian lithium deposits. He claimed that Russia was thereby getting ahead of the United States. In fact, it was the Australian company European Lithium that received the mining rights for lithium deposits in Donetsk Oblast and Kirovohrad Oblast at the end of 2021. Almost at the same time, the Chinese company Chengxin Lithium had also applied for this, but was rejected.[54][55]

Although the US government estimates that Russia's economic losses from the war and Western sanctions will amount to around $1.3 trillion by 2025, and the direct financial expenditure for conducting the war is estimated at around $250 billion (as of autumn 2024) - costs that Russia could not have foreseen. However, according to a study published in summer 2022 by the Canadian think tank SecDev, Russia controlled energy reserves, metals and minerals worth at least $12.4 trillion in the occupied territories in Donbas, including 41 coal fields (63 percent of Ukraine's coal reserves), 27 natural gas fields, 9 oil fields, 6 iron ore deposits, 2 titanium ore deposits, 1 strontium and 1 uranium deposit, 1 gold deposit and 1 large limestone quarry. The total value of national raw material stocks in Ukraine is estimated at over $26 trillion.[54] The value of lithium and rare earths in Ukraine is estimated at around $11.5 trillion.[55] In January 2024, the Russian occupation administration in Donetsk Oblast granted the Russian Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources a “permission” to mine lithium in the Shevchenko deposit near Kurakhovo, where the lithium deposit is estimated to be worth hundreds of billions of US dollars.[54]

The green transformation or energy transition in Europe is threatening Russia's usual business and existence model, the trade in fossil fuels. The energy transition is creating new dependencies, because technologies such as wind turbines, photovoltaics and electric car batteries are dependent on lithium and rare earths. Mining them in Europe would be too expensive due to high environmental regulations, low acceptance among the population and considerable labor costs (which is why they were imported from China and countries in the global south); however, Ukraine ranks fourth in the world with 800 deposits of 94 different mineral resources and would thus displace Russia as a trading partner. A few months before the start of the Russian invasion, the EU and Ukraine had signed a Green Deal or a transformation program for Ukraine, because the Ukrainian economy was at the time the most energy-intensive in the world with the most ineffective and expensive thermal power generation. The program envisaged further economic integration between the two contracting parties and climate neutrality in Ukraine by 2060. In addition to areas for the expansion of wind and solar energy, Ukraine also has infrastructure to transport green hydrogen to the EU. In addition, 22 of the 30 raw materials that the EU classified as strategically important are available in large quantities in Ukraine. Russia could only benefit from the energy transition in Europe if it acquired the resources and infrastructure on Ukrainian soil. Europe would then be even more dependent on Russia. If Russia were to achieve its war goals, Russia could steal and gain more than it would lose in peace through reduced exports to Europe.[54][55]

The Russian elite, especially Russian generals, had invested their assets and property in Ukraine for money laundering before the begin of the conflict.[53]

Prelude

There was a large Russian military build-up near the Ukraine border in March and April 2021,[56] and again in both Russia and Belarus from October 2021 onward.[57] Members of the Russian government, including Putin, repeatedly denied having plans to invade or attack Ukraine, with denials being issued up to the day before the invasion.[58][59][60] The decision to invade Ukraine was reportedly made by Putin and a small group of war hawks or siloviki in Putin's inner circle, including national security adviser Nikolai Patrushev and defence minister Sergei Shoigu.[61] Reports of an alleged leak of Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) documents by US intelligence sources said that the FSB had not been aware of Putin's plan to invade.[62]

In July 2021, Putin published an essay "On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians", in which he called Ukraine "historically Russian lands" and claimed there is "no historical basis" for the "idea of Ukrainian people as a nation separate from the Russians".[63][64] Days before the invasion, Putin claimed that Ukraine never had "real statehood" and that modern Ukraine was a mistake created by the Russian Bolsheviks.[65] American historian Timothy Snyder described Putin's ideas as Russian imperialism.[66] British journalist Edward Lucas described it as historical revisionism. Other observers found that Russia's leadership held a distorted view of Ukraine, as well as of its own history,[67] and that these distortions were propagated through the state.[68]

In December 2021, Russia issued an ultimatum to the West, which included demands that NATO end all activity in its Eastern European member states and ban Ukraine or any former Soviet state from ever joining the alliance.[69][70] Russia's government said NATO was a threat and warned of a military response if it followed an "aggressive line".[71] Some of the demands had already been ruled out by NATO. A senior US official said the US was willing to discuss the proposals, but added that there were some "that the Russians know are unacceptable".[69] Eastern European states willingly joined NATO for security reasons, and the last time a country bordering Russia had joined was in 2004. Ukraine had not yet applied, and some members were wary of letting it join.[72] Barring Ukraine would go against NATO's "open door" policy, and against treaties agreed to by Russia itself.[73] NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg replied that "Russia has no say" on whether Ukraine joins, and "has no right to establish a sphere of influence to try to control their neighbours".[74] NATO underlined that it is a defensive alliance, and that it had co-operated with Russia until the latter annexed Crimea.[73] It offered to improve communication with Russia, and to negotiate limits on missile placements and military exercises, provided Russia withdrew its troops from Ukraine's borders,[75] but Russia did not do so.

Western leaders vowed that heavy sanctions would be imposed should Putin choose to invade rather than to negotiate.[76] French President Emmanuel Macron[77] and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz met Putin in February 2022 to dissuade him from an invasion. According to Scholz, Putin told him that Ukraine should not be an independent state.[78] Scholz told Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to declare Ukraine a neutral country and renounce its aspirations to join NATO. Zelenskyy replied that Putin could not be trusted to abide by such a settlement.[79] Ukraine had been a neutral country in 2014 when Russia occupied Crimea and invaded the Donbas.[80][81] On 19 February, Zelenskyy made a speech at the Munich Security Conference, calling for Western powers to drop their policy of "appeasement" towards Moscow and give a clear time-frame for when Ukraine could join NATO.[82] As political analysts Taras Kuzio and Vladimir Socor agree, "when Russia made its decision to invade Ukraine, that country was more remote than ever not only from NATO membership but from any track that might lead to membership".[70]

Putin's invasion announcement

On 21 February, Putin announced that Russia recognized the Russian-controlled territories of Ukraine as independent states: the Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic. The following day, Russia announced that it was sending troops into these territories as "peacekeepers",[83] and the Federation Council of Russia authorised the use of military force abroad.[84]

Before 5 a.m. Kyiv time on 24 February, Putin, in another speech, announced a "special military operation", which effectively declared war on Ukraine.[85][86] Putin said the operation was to "protect the people" of the Russian-controlled breakaway republics. He falsely claimed that they had "been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kyiv regime."[87] Putin said that Russia was being threatened: he falsely claimed that Ukrainian government officials were neo-Nazis under Western control, that Ukraine was developing nuclear weapons, and that a hostile NATO was building up its forces and military infrastructure in Ukraine.[88] He said Russia sought the "demilitarization and denazification" of Ukraine, and espoused views challenging the legitimacy of the Ukrainian state.[89][65] Putin said he had no plans to occupy Ukraine.[88]

The invasion began within minutes of Putin's speech.[85]

Events

The invasion began at dawn on 24 February.[85][90] It was described as the biggest attack on a European country and the first full-scale war in Europe[91] since the Second World War. Russia launched a simultaneous ground and air attack.[92][93] Russian missiles struck targets throughout Ukraine,[94] and Russian troops invaded from the north, east, and south.[95] Russia did not officially declare war.[96] It was Russia's largest combined arms operation since the Soviet Union's Battle of Berlin in 1945.[citation needed] Fighting began in Luhansk Oblast at 3:40 a.m. Kyiv time near Milove on the border with Russia.[97] The main infantry and tank attacks were launched in four spearheads, creating a northern front launched towards Kyiv from Belarus, a southern front from Crimea, a southeastern front from Russian-controlled Donbas, and an eastern front from Russia towards Kharkiv and Sumy.[98] Russian vehicles were subsequently marked with a white Z military symbol (a non-Cyrillic letter), believed to be a measure to prevent friendly fire.[99]

Immediately after the invasion began, Zelenskyy declared martial law in Ukraine in a first video speech.[100] The same evening, he ordered a general mobilisation of all Ukrainian males between 18 and 60 years old,[101] prohibiting them from leaving the country.[102] Wagner Group mercenaries and Kadyrovites contracted by the Kremlin reportedly made several attempts to assassinate Zelenskyy, including an operation involving several hundred mercenaries meant to infiltrate Kyiv with the aim of killing the Ukrainian president.[103] The Ukrainian government said anti-war officials within Russia's FSB shared the plans with them.[104] Zelenskyy appeared defiant in video messages on 24 through 26 February, that he and his cabinet is still in Kyiv. On 26 February NATO met and its countries pledged military aid for Ukraine and on 27 February Germany called the invasion a historic watershed.[105] That day in the evening Putin put Russia's nuclear deterrence into alert.[106]

The Russian invasion was unexpectedly met by fierce Ukrainian resistance.[107] In Kyiv, Russia failed to take the city and was repulsed in the battles of Irpin, Hostomel, and Bucha. The Russians tried to encircle the capital, but its defenders under Oleksandr Syrskyi held their ground, effectively using Western Javelin anti-tank missiles and Stinger anti-aircraft missiles to thin Russian supply lines and stall the offensive.[108]

On the southern front, Russian forces had captured the regional capital of Kherson by 2 March. A column of Russian tanks and armoured vehicles was ambushed on 9 March in Brovary and sustained heavy losses that forced them to retreat.[109] The Russian army adopted siege tactics on the western front around the key cities of Chernihiv, Sumy and Kharkiv, but failed to capture them due to stiff resistance and logistical setbacks.[110] In Mykolaiv Oblast, Russian forces advanced as far as Voznesensk, but were repelled and pushed back south of Mykolaiv. On 25 March, the Russian Defence Ministry stated that the first stage of the "military operation" in Ukraine was "generally complete", that the Ukrainian military forces had suffered serious losses, and the Russian military would now concentrate on the "liberation of Donbas."[111] The "first stage" of the invasion was conducted on four fronts, including one towards western Kyiv from Belarus by the Russian Eastern Military District, comprising the 29th, 35th, and 36th Combined Arms Armies. A second axis, deployed towards eastern Kyiv from Russia by the Central Military District (northeastern front), comprised the 41st Combined Arms Army and the 2nd Guards Combined Arms Army.[112]

A third axis was deployed towards Kharkiv by the Western Military District (eastern front), with the 1st Guards Tank Army and 20th Combined Arms Army. A fourth, southern front originating in occupied Crimea and Russia's Rostov oblast with an eastern axis towards Odesa and a western area of operations toward Mariupol was opened by the Southern Military District, including the 58th, 49th, and 8th Combined Arms Army, the latter also commanding the 1st and 2nd Army Corps of the Russian separatist forces in Donbas.[112] By 7 April, Russian troops deployed to the northern front by the Russian Eastern Military District pulled back from the Kyiv offensive, reportedly to resupply and redeploy to the Donbas region in an effort to reinforce the renewed invasion of southeastern Ukraine. The northeastern front, including the Central Military District, was similarly withdrawn for resupply and redeployment to southeastern Ukraine.[112][113] On 26 April, delegates from the US and 40 allied nations met at Ramstein Air Base in Germany to discuss the formation of a coalition that would provide economic support in addition to military supplies and refitting to Ukraine.[114] Following Putin's Victory Day speech in early May, US Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines said no short term resolution to the invasion should be expected.[115]

Ukraine's reliance on Western-supplied equipment constrained operational effectiveness, as supplying countries feared that Ukraine would use Western-made matériel to strike targets in Russia.[116] Military experts disagreed on the future of the conflict; some suggested that Ukraine should trade territory for peace,[117] while others believed that Ukraine could maintain its resistance due to Russian losses.[118]

By 30 May, disparities between Russian and Ukrainian artillery were apparent, with Ukrainian artillery being vastly outgunned, in terms of both range and number.[116] In response to US President Joe Biden's indication that enhanced artillery would be provided to Ukraine, Putin said that Russia would expand its invasion front to include new cities in Ukraine. In apparent retribution, Putin ordered a missile strike against Kyiv on 6 June after not directly attacking the city for several weeks.[119] On 10 June 2022, deputy head of the SBU Vadym Skibitsky stated that during the Severodonetsk campaign, the frontlines were where the future of the invasion would be decided: "This is an artillery war now, and we are losing in terms of artillery. Everything now depends on what [the west] gives us. Ukraine has one artillery piece to 10 to 15 Russian artillery pieces. Our western partners have given us about 10% of what they have."[120]

On 29 June, Reuters reported that US Intelligence Director Avril Haines, in an update of past US intelligence assessments on the Russian invasion, said that US intelligence agencies agree that the invasion will continue "for an extended period of time ... In short, the picture remains pretty grim and Russia's attitude toward the West is hardening."[121] On 5 July, BBC reported that extensive destruction by the Russian invasion would cause immense financial damage to Ukraine's reconstruction economy, with Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal telling nations at a reconstruction conference in Switzerland that Ukraine needs $750bn for a recovery plan and Russian oligarchs should contribute to the cost.[122]

Initial invasion (24 February – 7 April 2022)

The invasion began on 24 February, launched out of Belarus to target Kyiv, and from the northeast against the city of Kharkiv. The southeastern front was conducted as two separate spearheads, from Crimea and the southeast against Luhansk and Donetsk.

Kyiv and northern front

Russian efforts to capture Kyiv included a probative spearhead on 24 February, from Belarus south along the west bank of the Dnipro River. The apparent intent was to encircle the city from the west, supported by two separate axes of attack from Russia along the east bank of the Dnipro: the western at Chernihiv, and from the east at Sumy. These were likely intended to encircle Kyiv from the northeast and east.[92][93]

Russia tried to seize Kyiv quickly, with Spetsnaz infiltrating into the city supported by airborne operations and a rapid mechanised advance from the north, but failed.[123][124] The United States contacted Zelenskyy and offered to help him flee the country, lest the Russian Army attempt to kidnap or kill him on seizing Kyiv; Zelenskyy responded that "The fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride."[125] The Washington Post, which described the quote as "one of the most-cited lines of the Russian invasion", was not entirely sure of the comment's accuracy. Reporter Glenn Kessler said it came from "a single source, but on the surface it appears to be a good one."[126] Russian forces advancing on Kyiv from Belarus gained control of the ghost town of Chernobyl.[127] Russian Airborne Forces attempted to seize two key airfields near Kyiv, launching an airborne assault on Antonov Airport,[128] and a similar landing at Vasylkiv, near Vasylkiv Air Base, on 26 February.[129]

By early March, Russian advances along the west side of the Dnipro were limited by Ukrainian defences.[93][92] As of 5 March, a large Russian convoy, reportedly 64 kilometres (40 mi) long, had made little progress toward Kyiv.[130] The London-based think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) assessed Russian advances from the north and east as "stalled."[131] Advances from Chernihiv largely halted as a siege began there. Russian forces continued to advance on Kyiv from the northwest, capturing Bucha, Hostomel and Vorzel by 5 March,[132][133] though Irpin remained contested as of 9 March.[134] By 11 March, the lengthy convoy had largely dispersed and taken cover.[135] On 16 March, Ukrainian forces began a counter-offensive to repel Russian forces.[136] Unable to achieve a quick victory in Kyiv, Russian forces switched their strategy to indiscriminate bombing and siege warfare.[137][138] On 25 March, a Ukrainian counter-offensive retook several towns to the east and west of Kyiv, including Makariv.[139][140] Russian troops in the Bucha area retreated north at the end of March. Ukrainian forces entered the city on 1 April.[141] Ukraine said it had recaptured the entire region around Kyiv, including Irpin, Bucha, and Hostomel, and uncovered evidence of war crimes in Bucha.[142] On 6 April, NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg said that the Russian "retraction, resupply, and redeployment" of their troops from the Kyiv area should be interpreted as an expansion of Putin's plans for Ukraine, by redeploying and concentrating his forces on eastern Ukraine.[113] Kyiv was generally left free from attack apart from isolated missile strikes. One did occur while UN Secretary-General António Guterres was visiting Kyiv on 28 April to discuss the survivors of the siege of Mariupol with Zelenskyy. One person was killed and several were injured in the attack.[143]

Northeastern front

Russian forces advanced into Chernihiv Oblast on 24 February, besieging its administrative capital within four days of fighting. On 25 February Ukrainian forces lost control over Konotop.[144][145] As street fighting took place in the city of Sumy, just 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the Russo-Ukrainian border, Ukrainian forces claimed that on 28 February that 100 Russian armoured vehicles had been destroyed and dozens of soldiers captured following a Bayraktar TB2 drone and artillery attack on a large Russian column near Lebedyn in Sumy Oblast.[146] Russian forces also attacked Okhtyrka, deploying thermobaric weapons.[147]

On 4 March, Frederick Kagan wrote that the Sumy axis was then "the most successful and dangerous Russian avenue of advance on Kyiv", and commented that the geography favoured mechanised advances as the terrain "is flat and sparsely populated, offering few good defensive positions."[92] Travelling along highways, Russian forces reached Brovary, an eastern suburb of Kyiv, on 4 March.[93][92] The Pentagon confirmed on 6 April that the Russian army had left Chernihiv Oblast, but Sumy Oblast remained contested.[148] On 7 April, the governor of Sumy Oblast said that Russian troops were gone, but had left behind rigged explosives and other hazards.[149]

Southern front

On 24 February, Russian forces took control of the North Crimean Canal, allowing Crimea to obtain water from the Dnieper, which had been cut off since 2014.[150] On 26 February, the siege of Mariupol began as the attack moved east linking to separatist-held Donbas.[147][151] En route, Russian forces entered Berdiansk and captured it.[152] On 25 February, Russian units from the DPR were fighting near Pavlopil as they moved on Mariupol.[153] By evening, the Russian Navy began an amphibious assault on the coast of the Sea of Azov 70 kilometres (43 mi) west of Mariupol. A US defence official said that Russian forces were deploying thousands of marines from this beachhead.[154]

The Russian 22nd Army Corps approached the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant on 26 February[155] and besieged Enerhodar. A fire began,[156][157] but the Ukrainian military said that essential equipment was undamaged.[158] A third Russian attack group from Crimea moved northwest and captured the bridge over the Dnieper.[159] On 2 March, Russian troops took Kherson; this was the first major city to fall to Russian forces.[160] Russian troops moved on Mykolaiv and attacked it two days later. They were repelled by Ukrainian forces.[161]

After renewed missile attacks on 14 March in Mariupol, the Ukrainian government said more than 2,500 had died.[162] By 18 March, Mariupol was completely encircled and fighting reached the city centre, hampering efforts to evacuate civilians.[163] On 20 March, an art school sheltering around 400 people, was destroyed by Russian bombs.[164] The Russians demanded surrender, and the Ukrainians refused.[98][165] On 27 March, Ukrainian deputy prime minister Olha Stefanishyna said that "(m)ore than 85 percent of the whole town is destroyed."[166]

Putin told Emmanuel Macron in a phone call on 29 March that the bombardment of Mariupol would only end when the Ukrainians surrendered.[167] On 1 April, Russian troops refused safe passage into Mariupol to 50 buses sent by the United Nations to evacuate civilians, as peace talks continued in Istanbul.[168] On 3 April, following the retreat of Russian forces from Kyiv, Russia expanded its attack on southern Ukraine further west, with bombardment and strikes against Odesa, Mykolaiv, and the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant.[169][170]

Eastern front

In the east, Russian troops attempted to capture Kharkiv, less than 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the Russian border,[171] and met strong Ukrainian resistance. On 25 February, the Millerovo air base was attacked by Ukrainian military forces with OTR-21 Tochka missiles, which according to Ukrainian officials, destroyed several Russian Air Force planes and started a fire.[172] On 1 March, Denis Pushilin, head of the DPR, announced that DPR forces had almost completely surrounded the city of Volnovakha.[173] On 2 March, Russian forces were repelled from Sievierodonetsk during an attack against the city.[174] On the same day, Ukrainian forces initiated a counter-offensive on Horlivka,[175] controlled by the DPR.[176] Izium was captured by Russian forces on 1 April[177] after a monthlong battle.[178]

On 25 March, the Russian defence ministry said it would seek to occupy major cities in eastern Ukraine.[179] On 31 March, PBS News reported renewed shelling and missile attacks in Kharkiv, as bad or worse than before, as peace talks with Russia were to resume in Istanbul.[180]

Amid the heightened Russian shelling of Kharkiv on 31 March, Russia reported a helicopter strike against an oil supply depot approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) north of the border in Belgorod, and accused Ukraine of the attack.[181] Ukraine denied responsibility.[182] By 7 April, the renewed massing of Russian invasion troops and tank divisions around the towns of Izium, Sloviansk, and Kramatorsk prompted Ukrainian government officials to advise the remaining residents near the eastern border of Ukraine to evacuate to western Ukraine within 2–3 days, given the absence of arms and munitions previously promised to Ukraine by then.[183]

Southeastern front (8 April – 5 September 2022)

By 17 April, Russian progress on the southeastern front appeared to be impeded by opposing Ukrainian forces in the large, heavily fortified Azovstal steel mill and surrounding area in Mariupol.[184]

On 19 April, The New York Times confirmed that Russia had launched a renewed invasion front referred to as an "eastern assault" across a 480-kilometre (300 mi) front extending from Kharkiv to Donetsk and Luhansk, with simultaneous missile attacks again directed at Kyiv in the north and Lviv in western Ukraine.[185] As of 30 April, a NATO official described Russian advances as "uneven" and "minor."[186] An anonymous US Defence official called the Russian offensive "very tepid", "minimal at best", and "anaemic."[187] In June 2022 the chief spokesman for the Russian Ministry of Defence Igor Konashenkov revealed that Russian troops were divided between the Army Groups "Centre" commanded by Colonel General Aleksander Lapin and "South" commanded by Army General Sergey Surovikin.[188] On 20 July, Lavrov announced that Russia would respond to the increased military aid being received by Ukraine from abroad as justifying the expansion of its special military operation to include objectives in both the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts.[189]

Russian Ground Forces started recruiting volunteer battalions from the regions in June 2022 to create a new 3rd Army Corps within the Western Military District, with a planned strength estimated at 15,500–60,000 personnel.[190] Its units were deployed to the front around the time of Ukraine's 9 September Kharkiv oblast counteroffensive, in time to join the Russian retreat, leaving behind tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and personnel carriers: the 3rd Army Corps "melted away" according to Forbes, having little or no impact on the battlefield along with other irregular forces.[191]

Fall of Mariupol

On 13 April, Russian forces intensified their attack on the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works in Mariupol, and the remaining Ukrainian personnel defending it.[192] By 17 April, Russian forces had surrounded the factory. Ukrainian prime minister Denys Shmyhal said that the Ukrainian soldiers had vowed to ignore the renewed ultimatum to surrender and to fight to the last soul.[184] On 20 April, Putin said that the siege of Mariupol could be considered tactically complete, since the 500 Ukrainian troops entrenched in bunkers within the Azovstal iron works and estimated 1,000 Ukrainian civilians were completely sealed off from any type of relief.[193]

After consecutive meetings with Putin and Zelenskyy, UN Secretary-General Guterres on 28 April said he would attempt to organise an emergency evacuation of survivors from Azovstal in accordance with assurances he had received from Putin on his visit to the Kremlin.[194] On 30 April, Russian troops allowed civilians to leave under UN protection.[195] By 3 May, after allowing approximately 100 Ukrainian civilians to depart from the Azovstal steel factory, Russian troops renewed their bombardment of the steel factory.[196] On 6 May, The Daily Telegraph reported that Russia had used thermobaric bombs against the remaining Ukrainian soldiers, who had lost contact with the Kyiv government; in his last communications, Zelenskyy authorised the commander of the besieged steel factory to surrender as necessary under the pressure of increased Russian attacks.[197] On 7 May, the Associated Press reported that all civilians were evacuated from the Azovstal steel works at the end of the three-day ceasefire.[198]

After the last civilians evacuated from the Azovstal bunkers, nearly two thousand Ukrainian soldiers remained barricaded there, 700 of them injured. They were able to communicate a plea for a military corridor to evacuate, as they expected summary execution if they surrendered to Russian forces.[199] Reports of dissent within the Ukrainian troops at Azovstal were reported by Ukrainska Pravda on 8 May indicating that the commander of the Ukrainian marines assigned to defend the Azovstal bunkers made an unauthorised acquisition of tanks, munitions, and personnel, broke out from the position there and fled. The remaining soldiers spoke of a weakened defensive position in Azovstal as a result, which allowed progress to advancing Russian lines of attack.[200] Ilia Somolienko, deputy commander of the remaining Ukrainian troops barricaded at Azovstal, said: "We are basically here dead men. Most of us know this and it's why we fight so fearlessly."[201]

On 16 May, the Ukrainian General staff announced that the Mariupol garrison had "fulfilled its combat mission" and that final evacuations from the Azovstal steel factory had begun. The military said that 264 service members were evacuated to Olenivka under Russian control, while 53 of them who were "seriously injured" had been taken to a hospital in Novoazovsk also controlled by Russian forces.[202][203] Following the evacuation of Ukrainian personnel from Azovstal, Russian and DPR forces fully controlled all areas of Mariupol. The end of the battle also brought an end to the Siege of Mariupol. Russia press secretary Dmitry Peskov said Russian President Vladimir Putin had guaranteed that the fighters who surrendered would be treated "in accordance with international standards" while Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said in an address that "the work of bringing the boys home continues, and this work needs delicacy—and time." Some prominent Russian lawmakers called on the government to deny prisoner exchanges for members of the Azov Regiment.[204]

Fall of Sievierodonetsk and Lysychansk

A Russian missile attack on Kramatorsk railway station in the city of Kramatorsk took place on 8 April, reportedly killing at least 52 people[205] and injuring as many as 87 to 300.[206] On 11 April, Zelenskyy said that Ukraine expected a major new Russian offensive in the east.[207] American officials said that Russia had withdrawn or been repulsed elsewhere in Ukraine, and therefore was preparing a retraction, resupply, and redeployment of infantry and tank divisions to the southeastern Ukraine front.[208][209] Military satellites photographed extensive Russian convoys of infantry and mechanised units deploying south from Kharkiv to Izium on 11 April, apparently part of the planned Russian redeployment of its northeastern troops to the southeastern front of the invasion.[210]

On 18 April, with Mariupol almost entirely overtaken by Russian forces, the Ukrainian government announced that the second phase of the reinforced invasion of the Donetsk, Luhansk and Kharkiv oblasts had intensified with expanded invasion forces occupying of the Donbas.[211]

On 22 May, the BBC reported that after the fall of Mariupol, Russia had intensified offensives in Luhansk and Donetsk while concentrating missile attacks and intense artillery fire on Sievierodonetsk, the largest city under Ukrainian control in Luhansk province.[212]

On 23 May, Russian forces were reported entering the city of Lyman, fully capturing the city by 26 May.[213][214] Ukrainian forces were reported leaving Sviatohirsk.[215] By 24 May, Russian forces captured the city of Svitlodarsk.[216] On 30 May, Reuters reported that Russian troops had breached the outskirts of Sievierodonetsk.[217] By 2 June, The Washington Post reported that Sievierodonetsk was on the brink of capitulation to Russian occupation with over 80 per cent of the city in the hands of Russian troops.[218] On 3 June, Ukrainian forces reportedly began a counter-attack in Sievierodonetsk. By 4 June, Ukrainian government sources claimed 20% or more of the city had been recaptured.[219]

On 12 June, it was reported that possibly as many as 800 Ukrainian civilians (as per Ukrainian estimates) and 300–400 soldiers (as per Russian sources) were besieged at the Azot chemical factory in Severodonetsk.[220][221] With the Ukrainian defences of Severodonetsk faltering, Russian invasion troops began intensifying their attack upon the neighbouring city of Lysychansk as their next target city in the invasion.[222] On 20 June it was reported that Russian troops continued to tighten their grip on Severodonetsk by capturing surrounding villages and hamlets surrounding the city, most recently the village of Metelkine.[223]

On 24 June, CNN reported that, amid continuing scorched-earth tactics being applied by advancing Russian troops, Ukraine's armed forces were ordered to evacuate the Severodonetsk; several hundred civilians taking refuge in the Azot chemical plant were left behind in the withdrawal, with some comparing their plight to that of the civilians at the Azovstal steel works in Mariupol in May.[224] On 3 July, CBS announced that the Russian defence ministry claimed that the city of Lysychansk had been captured and occupied by Russian forces.[225] On 4 July, The Guardian reported that after the fall of the Luhansk oblast, that Russian invasion troops would continue their invasion into the adjacent Donetsk Oblast to attack the cities of Sloviansk and Bakhmut.[226]

Kharkiv front

On 14 April, Ukrainian troops reportedly blew up a bridge between Kharkiv and Izium used by Russian forces to redeploy troops to Izium, impeding the Russian convoy.[227]

On 5 May, David Axe writing for Forbes stated that the Ukrainian army had concentrated its 4th and 17th Tank Brigades and the 95th Air Assault Brigade around Izium for possible rearguard action against the deployed Russian troops in the area; Axe added that the other major concentration of Ukraine's forces around Kharkiv included the 92nd and 93rd Mechanised Brigades which could similarly be deployed for rearguard action against Russian troops around Kharkiv or link up with Ukrainian troops contemporaneously being deployed around Izium.[228]

On 13 May, BBC reported that Russian troops in Kharkiv were being retracted and redeployed to other fronts in Ukraine following the advances of Ukrainian troops into surrounding cities and Kharkiv itself, which included the destruction of strategic pontoon bridges built by Russian troops to cross over the Seversky Donets river and previously used for rapid tank deployment in the region.[229]

Kherson-Mykolaiv front

Missile attacks and bombardment of the key cities of Mykolaiv and Odesa continued as the second phase of the invasion began.[185] On 22 April 2022, Russia's Brigadier General Rustam Minnekayev in a defence ministry meeting said that Russia planned to extend its Mykolaiv–Odesa front after the siege of Mariupol further west to include the breakaway region of Transnistria on the Ukrainian border with Moldova.[230] The Ministry of Defence of Ukraine called this plan imperialism and said that it contradicted previous Russian claims that it did not have territorial ambitions in Ukraine and also that the statement admitted that "the goal of the 'second phase' of the war is not victory over the mythical Nazis, but simply the occupation of eastern and southern Ukraine."[230] Georgi Gotev of EURACTIV noted on 22 April that Russian occupation from Odesa to Transnistria would transform Ukraine into a landlocked nation with no practical access to the Black Sea.[231] Russia resumed its missile strikes on Odesa on 24 April, destroying military facilities and causing two dozen civilian casualties.[232]

Explosions destroyed two Russian broadcast towers in Transnistria on 27 April that had primarily rebroadcast Russian television programming, Ukrainian sources said.[233] Russian missile attacks at the end of April destroyed runways in Odesa.[234] In the week of 10 May, Ukrainian troops began to dislodge Russian forces from Snake Island in the Black Sea approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Odesa.[235] Russia said on 30 June 2022 that it had withdrawn its troops from the island, once their objectives had been completed.[236]

On 23 July, CNBC reported a Russian missile strike on the Ukrainian port of Odesa, swiftly condemned by world leaders amid a recent UN- and Turkish-brokered deal to secure a sea corridor for exports of grains and other foodstuffs.[237] On 31 July, CNN reported significantly intensified rocket attacks and bombing of Mykolaiv by Russians, which also killed Ukrainian grain tycoon Oleksiy Vadaturskyi.[238]

Zaporizhzhia front

Russian forces continued to fire missiles and drop bombs on the key cities of Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia.[185] Russian missiles destroyed the Dnipro International Airport on 10 April 2022.[239] On 2 May, the UN, reportedly with the cooperation of Russian troops, evacuated about 100 survivors from the siege of Mariupol to the village of Bezimenne near Donetsk, from whence they would move to Zaporizhzhia.[240] On 28 June, Reuters reported that a Russian missile attack on the city of Kremenchuk northwest of Zaporizhzhia detonated in a public mall and caused at least 18 deaths. France's Emmanuel Macron called it a "war crime."[241]

Ukrainian nuclear agency Energoatom called the situation at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant "extremely tense", although it was still operated by its Ukrainian staff. As many as 500 Russian soldiers controlled the plant; Kyiv's nuclear agency said they were shelling nearby areas and storing weapons and "missile systems" there. Almost the entire country went on air raid alert. "They already shell the other side of the river Dnipro and the territory of Nikopol," Energoatom president Pedro Kotin said.[242] Russia agreed on 19 August to allow IAEA inspectors access to the Zaporizhzhia plant after a phone call from Macron to Putin. As of July 2023, however, access to the plant remained limited and required extensive negotiation.[243]

Russia reported that 12 attacks with explosions from 50 artillery shells had been recorded by 18 August at the plant and the company town of Enerhodar.[244] Tobias Ellwood, chair of the UK's Defence Select Committee, said on 19 August that any deliberate damage to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant that could cause radiation leaks would be a breach of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, under which an attack on a member state of NATO is an attack on them all. US congressman Adam Kinzinger said the following day that any radiation leak would kill people in NATO countries, an automatic activation of Article 5.[245][246]

Shelling hit coal ash dumps at the neighbouring coal-fired power station on 23 August, and the ash was on fire on 25 August. The 750 kV transmission line to the Dniprovska substation, the only one of the four 750 kV transmission lines still undamaged and cut by military action, passes over the ash dumps. At 12:12 p.m. on 25 August, the line was cut off due to the fire, disconnecting the plant and its two operating reactors from the national grid for the first time since its startup in 1985. In response, backup generators and coolant pumps for reactor 5 started up, and reactor 6 reduced generation.[247]

Incoming power was still available across the 330 kV line to the substation at the coal-fired station, so the diesel generators were not essential for cooling reactor cores and spent fuel pools. The 750 kV line and reactor 6 resumed operation at 12:29 p.m., but the line was cut by fire again two hours later. The line, but not the reactors, resumed operation again later that day.[247] On 26 August, one reactor restarted in the afternoon and another in the evening, resuming electricity supplies to the grid.[248] On 29 August 2022, an IAEA team led by Rafael Grossi went to the plant to investigate.[249] Lydie Evrard and Massimo Aparo were also on the team. No leaks had been reported at the plant before their arrival, but shelling had occurred days before.[250]

Russian annexations and occupation losses (6 September – 11 November 2022)

On 6 September 2022, Ukrainian forces launched a surprise counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region, beginning near Balakliia, led by General Syrskyi.[251] An emboldened Kyiv launched a counteroffensive 12 September around Kharkiv successful enough to make Russia admit losing key positions and for The New York Times to say that it dented the image of a "Mighty Putin". Kyiv sought more arms from the West to sustain the counteroffensive.[252] On 21 September 2022, Vladimir Putin announced a partial mobilisation and Minister of Defence Sergei Shoigu said 300,000 reservists would be called.[253] He also said that his country would use "all means" to "defend itself." Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to Zelenskyy, said that the decision was predictable and that it was an attempt to justify "Russia's failures."[254] British Foreign Office Minister Gillian Keegan called the situation an "escalation",[255] while former Mongolian president Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj accused Russia of using Russian Mongols as "cannon fodder."[256]

Russian annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts

In late September 2022, Russian-installed officials in Ukraine organised referendums on the annexation of the occupied territories of Ukraine. These included the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic in Russian-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine, as well as the Russian-appointed military administrations of Kherson Oblast and Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Denounced by Ukraine's government and its allies as sham elections, the elections' official results showed overwhelming majorities in favour of annexation.[257]

On 30 September 2022, Vladimir Putin announced the annexation of Ukraine's Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts in an address to both houses of the Russian parliament.[258] Ukraine, the United States, the European Union and the United Nations all denounced the annexation as illegal.[259]

Zaporizhzhia front

An IAEA delegation visited the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant on 3 September, and on 6 September reported damage and security threats caused by external shelling and the presence of occupying troops in the plant.[260] On 11 September, at 3:14 a.m., the sixth and final reactor was disconnected from the grid, "completely stopping" the plant. Energoatom said that preparations were "underway for its cooling and transfer to a cold state."[261]

In the early hours of 9 October 2022, Russian Armed Forces carried out an airstrike on a residential building in Zaporizhzhia, killing 13 civilians and injuring 89 others.[262]

Kherson counteroffensive

On 29 August, Zelenskyy advisedly vowed the start of a full-scale counteroffensive in the southeast. He first announced a counteroffensive to retake Russian-occupied territory in the south concentrating on the Kherson-Mykolaiv region, a claim that was corroborated by the Ukrainian parliament as well as Operational Command South.[263]

On 4 September, Zelenskyy announced the liberation of two unnamed villages in Kherson Oblast and one in Donetsk Oblast. Ukrainian authorities released a photo showing the raising of the Ukrainian flag in Vysokopillia by Ukrainian forces.[264] Ukrainian attacks also continued along the southern frontline, though reports about territorial changes were largely unverifiable.[265] On 12 September, Zelenskyy said that Ukrainian forces had retaken a total of 6,000 square kilometres (2,300 sq mi) from Russia, in both the south and the east. The BBC stated that it could not verify these claims.[266]

In October, Ukrainian forces pushed further south towards the city of Kherson, taking control of 1,170 square kilometres (450 sq mi) of territory, with fighting extending to Dudchany.[267][268] On 9 November, defence minister Shoigu ordered Russian forces to leave part of Kherson Oblast, including the city of Kherson, and move to the eastern bank of the Dnieper.[269] On 11 November, Ukrainian troops entered Kherson, as Russia completed its withdrawal. This meant that Russian forces no longer had a foothold on the west (right) bank of the Dnieper.[270]

Kharkiv counteroffensive

Ukrainian forces launched another surprise counteroffensive on 6 September in the Kharkiv Oblast near Balakliia led by General Syrskyi.[251] By 7 September, Ukrainian forces had advanced some 20 kilometres (12 mi) into Russian occupied territory and claimed to have recaptured approximately 400 square kilometres (150 sq mi). Russian commentators said this was likely due to the relocation of Russian forces to Kherson in response to the Ukrainian offensive there.[271] On 8 September, Ukrainian forces captured Balakliia and advanced to within 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) of Kupiansk.[272] Military analysts said Ukrainian forces appeared to be moving towards Kupiansk, a major railway hub, with the aim of cutting off the Russian forces at Izium from the north.[273]

On 9 September, the Russian occupation administration of Kharkiv Oblast announced it would "evacuate" the civilian populations of Izium, Kupiansk and Velykyi Burluk. The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) said it believed Kupiansk would likely fall in the next 72 hours,[274] while Russian reserve units were sent to the area by both road and helicopter.[275] On the morning of 10 September, photos emerged claiming to depict Ukrainian troops raising the Ukrainian flag in the centre of Kupiansk,[276] and the ISW said Ukrainian forces had captured approximately 2,500 square kilometres (970 sq mi) by effectively exploiting their breakthrough.[277] Later in the day, Reuters reported that Russian positions in northeast Ukraine had "collapsed" in the face of the Ukrainian assault, with Russian forces forced to withdraw from their base at Izium after being cut off by the capture of Kupiansk.[278]

By 15 September, an assessment by UK's Ministry of Defence confirmed that Russia had either lost or withdrawn from almost all of their positions west of the Oskil river. The retreating units had also abandoned various high-value military assets.[279] The offensive continued pushing east and by 1 October, Ukrainian Armed Forces had liberated the key city of Lyman.[280]

Winter stalemate, attrition campaign and military surge (12 November 2022 – 7 June 2023)

After the end of the twin Ukrainian counteroffensives, the fighting shifted to a semi-deadlock during the winter,[281] with heavy casualties but reduced motion of the frontline.[282] Russia launched a self-proclaimed winter offensive in eastern Ukraine, but the campaign ended in "disappointment" for Moscow, with limited gains as the offensive stalled.[281][283] Analysts variously blamed the failure on Russia's lack of "trained men", and supply problems with artillery ammunition, among other problems.[281][283] Near the end of May, Mark Galeotti assessed that "after Russia's abortive and ill-conceived winter offensive, which squandered its opportunity to consolidate its forces, Ukraine is in a relatively strong position."[284]

On 7 February, The New York Times reported that Russians had newly mobilised nearly 200,000 soldiers to participate in the offensive in the Donbas, against Ukraine troops already wearied by previous fighting.[285] The Russian private military company Wagner Group took on greater prominence in the war,[286] leading "grinding advances" in Bakhmut with tens of thousands of recruits from prison battalions taking part in "near suicidal" assaults on Ukrainian positions.[283]

In late January 2023, fighting intensified in the southern Zaporizhzhia region, with both sides suffering heavy casualties.[287] In nearby southern parts of Donetsk Oblast, an intense, three-week Russian assault near the coal-mining town of Vuhledar was called the largest tank battle of the war to date, and ended in disaster for Russian forces, who lost "at least 130 tanks and armored personnel carriers" according to Ukrainian commanders. The British Ministry of Defence stated that "a whole Russian brigade was effectively annihilated."[288][289]

Battle of Bakhmut

Following defeat in Kherson and Kharkiv, Russian and Wagner forces focused on taking the city of Bakhmut and breaking the half year long stalemate that prevailed there since the start of the war. Russian forces sought to encircle the city, attacking from the north via Soledar. After taking heavy casualties, Russian and Wagner forces took control of Soledar on 16 January 2023.[290][291] By early February 2023, Bakhmut was facing attacks from north, south and east, with the sole Ukrainian supply lines coming from Chasiv Yar to the west.[292]

On 3 March 2023, Ukrainian soldiers destroyed two key bridges, creating the possibility for a controlled fighting withdrawal from eastern sectors of Bakhmut.[293] On 4 March, Bakhmut's deputy mayor told news services that there was street fighting in the city.[294] On 7 March, despite the city's near-encirclement, The New York Times reported that Ukrainian commanders were requesting permission from Kyiv to continue fighting against the Russians in Bakhmut.[295]

On 26 March, Wagner Group forces claimed to have fully captured the tactically significant Azom factory in Bakhmut.[296] Appearing before the House Committee on Armed Services on 29 March, General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, reported that, "for about the last 20, 21 days, the Russia have not made any progress whatsoever in and around Bakhmut." Milley described the severe casualties being inflicted upon the Russian forces there as a "slaughter-fest."[297]

By the beginning of May, the ISW assessed that Ukraine controlled only 1.89 square kilometres (0.73 sq mi) of the city, less than five percent.[298] On 18 May 2023, The New York Times reported that Ukrainian forces had launched a local counteroffensive, taking back swathes of territory to the north and south of Bakhmut over the course of a few days.[299] On 20 May 2023, the Wagner Group claimed full control over Bakhmut, and a victory in the battle was officially declared by Russia the next day,[300] following which Wagner forces retreated from the city in place of regular Russian units.[301]

2023 counteroffensives and summer campaign (8 June 2023 – 1 December 2023)

In June 2023, Ukrainian forces gradually launched a series of counteroffensives on multiple fronts, including Donetsk Oblast, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, and others.[302] On 8 June 2023, counteroffensive efforts focused near settlements such as Orikhiv, Tokmak, and Bakhmut.[303] However, counteroffensive operations faced stiff resistance from Russia,[304] and the American think tank Institute for the Study of War described the Russian defensive effort as having "an uncharacteristic degree of coherency."[305] By 12 June, Ukraine reported its fastest advance in seven months, claiming to have liberated several villages and advanced a total of 6.5 km. Russian military bloggers also reported that Ukraine had taken Blahodatne, Makarivka and Neskuchne, and were continuing to push southward.[306] Ukraine continued to liberate settlements over the next few months, raising the Ukrainian flag over the settlement of Robotyne in late August.[307]

On 24 June, the Wagner Group launched a brief rebellion against the Russian government, capturing several cities in western Russia largely unopposed before marching towards Moscow.[308] This came as the culmination of prolonged infighting and power struggles between Wagner and the Russian Ministry of Defence.[309] After about 24 hours, the Wagner Group backed down[310] and agreed to a peace deal in which Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin would go into exile in Belarus, and his forces would be free from prosecution.[308] On 27 June, the UK's Ministry of Defence reported that Ukraine were "highly likely" to have reclaimed territory in the eastern Donbas region occupied by Russia since 2014 among its advances. Pro-Russian bloggers also reported that Ukrainian forces had made gains in the southern Kherson Oblast, establishing a foothold on the left bank of the Dnipro river.[311]

In August, The Guardian reported that Ukraine had become the most mined country in the world, with Russia laying millions of mines attempting to thwart Ukraine's counteroffensive. The vast minefields forced Ukraine to extensively de-mine areas to allow advances. Ukrainian officials reported shortages of men and equipment as Ukrainian soldiers unearthed five mines for every square metre in certain places.[312]

Following Russia pulling out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, the conflict on the Black Sea escalated with Ukraine targeting Russian ships. On 4 August, Ukrainian security service sources reported that the Russian landing ship Olenegorsky Gornyak had been hit and damaged by an unmanned naval drone. Video footage released by Ukraine's security services appeared to show the drone striking the ship, with another video showing the ship seemingly listing to one side.[313] On 12 September, both Ukrainian and Russian sources reported that Russian naval targets in Sevastopol had been struck by unconfirmed weaponry, damaging two military vessels, one of them reportedly a submarine.[314] Ukraine also reported that several oil and gas drilling platforms on the Black Sea held by Russia since 2015 had been retaken.[315]

In September 2023, Ukrainian intelligence estimated that Russia had deployed over 420,000 troops in Ukraine.[316]

On 21 September, Russia began missile strikes across Ukraine, damaging the country's energy facilities.[317] On 22 September, the US announced it would send long-range ATACMS missiles to Ukraine,[318] despite the reservations of some government officials.[319] The same day, the Ukrainian Main Directorate of Intelligence launched a missile strike on the Black Sea Fleet headquarters in Sevastopol, Crimea, killing several senior military officials.[320][321]

In October 2023, it was reported that there was a growth of mutinies among Russian troops due to the large number of losses in Russian offensives around Avdiivka with a lack of artillery, food, water and poor command also being reported.[322] By November, British intelligence said that recent weeks had "likely seen some of the highest Russian casualty rates of the war so far."[323]

In mid-to-late October 2023, Ukrainian marines—partly guided by defecting Russian troops—crossed the Dnipro River (the strategic barrier between eastern and western Ukraine), downstream of the destroyed Kakhovka Dam, to attack the Russian-held territory on the east side of the river. Despite heavy losses due to intense Russian shelling and aerial bombardment, disorganisation, and dwindling resources, Ukrainian brigades invading the Russian-held side of the river continued to inflict heavy casualties on Russian forces well into late December.[324][325]

On 1 December 2023, Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated that the Ukrainian counter-offensive was not successful, citing slower than expected results.[326] Zelenskyy also stated that it will be easier for Ukraine to regain the Crimean peninsula than the Donbas region in the east of the country, because the Donbas is heavily militarised and there are frequent pro-Russian sentiments.[327] In December 2023, multiple international media outlets described the Ukrainian counteroffensive as having failed to regain any significant amount of territory or meet any of its strategic objectives.[326][328][329]

Russian spring and summer campaigns and Ukrainian incursion (1 December 2023 – present)

Russian offensive

On 17 February 2024, Russia captured Avdiivka, a longtime stronghold for Ukraine that had been described as a "gateway" to nearby Donetsk.[330][331][332] ABC News stated that Russia could use the development to boost morale with the war largely at a stalemate close to its second anniversary.[333] Described by Forbes journalist David Axe as a pyrrhic Russian victory, the Russian 2nd and 41st Combined Arms Armies ended up with 16,000 men killed, tens of thousands wounded and around 700 vehicles lost before seizing the ruins of Avdiivka.[334]

Following severe equipment shortages and struggling to build or reactivate from long-term storage enough infantry fighting vehicles to equip front-line regiments and brigades, Russian forces resorted to using Chinese desertcross ″golf-carts″ as well as Chinese and Belarusian dirt bikes as replacements. The assaults with these vehicles have resulted in multiple Russian units being destroyed by the fortified Ukrainians.[335][336][337]

Ukraine's shortage of ammunition caused by political deadlock in the US Congress and a lack of production capacity in Europe contributed to the Ukrainian withdrawal from Avdiivka, and was "being felt across the front" according to Time. The shortage resulted in Ukraine having to ration its units to fire only 2,000 rounds per day, compared to an estimated 10,000 rounds fired daily by Russia.[338]

On 10 May 2024, Russia began a renewed offensive in Kharkiv Oblast. Russia managed to capture a dozen villages, and Ukraine had evacuated more than 11,000 people from the region since the start of the offensive by 25 May. Ukraine said on 17 May that its forces had slowed the Russian advance, and by 25 May Zelenskyy said that Ukrainian forces had secured "combat control" of areas where Russian troops entered the northeastern Kharkiv Oblast. Russian officials meanwhile said that they were "advancing in every direction" and that the goal was to create a "buffer zone" for embattled border regions.[339][340] The White House said on 7 June that the offensive had stalled and was unlikely to advance further.[341]

Following the Russian success in the battle of Avdiivka, their forces advanced northwest of it to form a salient, and by mid-April 2024 reached the settlement of Ocheretyne, capturing it in late April[342][343] and further expanding the salient in the succeeding months.[344] Russian forces also launched an offensive towards the city of Chasiv Yar in early April,[345] a strategically important settlement west of Bakhmut, and by early July had captured its easternmost district.[346][347] Another offensive in the direction of the city of Toretsk was launched on 18 June,[348] with the goal of capturing the city,[349] and according to Ukrainian military observer and spokesperson Nazar Voloshyn, flanking Chasiv Yar from the south.[350] Russian forces advanced to expand the salient northwest of Avdiivka in July, and on 19 July, made a breakthrough allowing them to begin advancing towards the operationally significant city of Pokrovsk.[351][352]

Ukrainian offensive into Russia

On 6 August 2024, Ukraine launched their first direct offensive into Russian territory, the largest of any pro-Ukrainian incursion since the invasion's inception, into the bordering Kursk Oblast.[353] The main axis of the initial advance centred in the direction of the town of Sudzha, located 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the border,[354] which was reported by President Zelenskyy to have been captured on 15 August.[355] Ukraine, taking advantage of the lack of experienced units and defenses along the border with Kursk Oblast, was able to quickly seize territory in the opening days of the incursion.[356] The incursion caused Russia to divert thousands of troops from occupied Ukrainian territory to counter the threat,[357][358] though not from Donetsk Oblast.[358]

Russian Donbas advances

Russian troops continued advancing in eastern Ukraine, notably at a faster pace than prior to the Kursk offensive,[359] including towards the strategically important city of Pokrovsk, where their number of forces had instead been increased.[360][361][362]

In late August 2024, Russian forces seized the city of Novohrodivka, southeast of Pokrovsk, bringing them within 8 kilometres of the city,[359] while capturing Krasnohorivka[363] and Ukrainsk,[364] near Pokrovsk and west of Donetsk city, in early September.[364] In late September, a Russian assault on the long-held city of Vuhledar began,[365] leading to its fall on 1 October.[366] Ukraine's 72nd Mechanised Brigade had defended the city for over two years, and said that the Russians had suffered "numerous losses" as they stormed the elevated city. Following the Russian capture, the city with a pre-war population of about 14,000 was described as a "sprawling ruin".[367]

On 30 October, Ukrainian Major General Dmytro Marchenko was reported to have said "our front has crumbled" due to a dwindling ammunition supply, problems with military recruitment, and poor leadership. He said Zelensky's victory plan was too heavily focused on seeking more Western support. Briefings from Western officials had also become more pessimistic about Ukraine's military situation.[368][369]

Battlespaces

Command

The supreme commanders-in-chief are the heads of state of the respective governments: President Vladimir Putin of Russia and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine. Putin has reportedly meddled in operational decisions, bypassing senior commanders and giving orders directly to brigade commanders.[370]

US general Mark Milley said that Ukraine's top military commander in the war, commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, "has emerged as the military mind his country needed. His leadership enabled the Ukrainian armed forces to adapt quickly with battlefield initiative against the Russians."[371] Russia began the invasion with no overall commander. The commanders of the four military districts were each responsible for their own offensives.[372]

After initial setbacks, the commander of the Russian Southern Military District, Aleksandr Dvornikov, was placed in overall command on 8 April 2022,[373] while still responsible for his own campaign. Russian forces benefited from the centralisation of command under Dvornikov,[374] but continued failures to meet expectations in Moscow led to multiple changes in overall command:[372]

- commander of the Eastern Military District Gennady Zhidko (Eastern Military District, 26 – 8 May October 2022)

- commander of the southern grouping of forces Sergei Surovikin (early October 2022 – 11 January 2023)

- commander-in-chief of the Russian Armed Forces Valerii Gerasimov (from 11 January 2023)

Russia has suffered a remarkably large number of casualties in the ranks of its officers, including 12 generals.[375]

Missile attacks and aerial warfare

Aerial warfare began the first day of the invasion. Dozens of missile attacks were recorded across both eastern and western Ukraine,[92][93] reaching as far west as Lviv.[172]

By September 2022, the Ukrainian air force had shot down about 55 Russian warplanes.[376] In mid-October, Russian forces launched missile strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure, intended to knock out energy facilities.[377] By late November, hundreds of civilians had been killed or wounded in the attacks,[378] and rolling blackouts had left millions without power.[379]

In December 2022, drones launched from Ukraine allegedly carried out several attacks on Dyagilevo and Engels air bases in western Russia, killing 10 and heavily damaging two Tu-95 aircraft.[380]

Crimea attacks

On 31 July 2022, Russian Navy Day commemorations were cancelled after a drone attack reportedly wounded several people at the Russian Black Sea Fleet headquarters in Sevastopol.[381] On 9 August 2022, large explosions were reported at Saky Air Base in western Crimea. Satellite imagery showed at least eight aircraft damaged or destroyed. Initial speculation attributed the explosions to long-range missiles, sabotage by special forces or an accident;[382] Ukrainian general Valerii Zaluzhnyi claimed responsibility on 7 September.[383]

The base is near Novofedorivka, a destination popular with tourists. Traffic backed up at the Crimean Bridge after the explosions with queues of civilians trying to leave the area.[384] A week later Russia blamed "sabotage" for explosions and a fire at an arms depot near Dzhankoi in northeastern Crimea that also damaged a railway line and power station. Russian regional head Sergei Aksyonov said that 2,000 people were evacuated from the area.[385] On 18 August, explosions were reported at Belbek Air Base north of Sevastopol.[386] On the morning of 8 October 2022 the Kerch Bridge, linking occupied Crimea to Russia, partially collapsed due to an explosion.[387] On 17 July 2023, there was another large explosion on the bridge.[388]

Russian attacks against Ukrainian civilian infrastructure

Since fall of 2022, Russia has carried out waves of strikes on Ukrainian electrical and water systems.[389] On 6 October the Ukrainian military reported that 86 Shahed 136 kamikaze drones had been launched by Russian forces in total, and between 30 September and 6 October Ukrainian forces had destroyed 24 out of 46 launched in that period.[390] On 8 October, it was announced that General of the Army Sergey Surovikin would be commanding all Russian forces in Ukraine on the strength of his novel air assault technique.[391]

On 16 October 2022, The Washington Post reported that Iran was planning to supply Russia with both drones and missiles.[392] On 18 October the US State Department accused Iran of violating Resolution 2231 by selling Shahed 131 and Shahed 136 drones to Russia,[393] agreeing with similar assessments by France and the United Kingdom. Iran denied sending any arms to Russia for the Ukraine war.[394] On 22 October France, Britain and Germany formally called for a UN investigation.[395] On 1 November, CNN reported that Iran was preparing to send ballistic missiles and other weapons to Russia for use in Ukraine.[396]

On 15 November 2022, Russia fired 85 missiles at the Ukrainian power grid, causing major power outages in Kyiv and neighboring regions.[397]

On 21 November, CNN quoted an intelligence assessment that Iran had begun to help Russia produce Iran-designed drones in Russia.[398] A 29 December New York Times report stated that the US was working to "choke off Iran's ability to manufacture the drones, make it harder for the Russians to launch the unmanned "kamikaze" aircraft and—if all else fails—to provide the Ukrainians with the defenses necessary to shoot them out of the sky."[399]

On 31 December, Putin in his New Year address called the war against Ukraine a "sacred duty to our ancestors and descendants" as missiles and drones rained down on Kyiv.[400]

On 10 March 2023, The New York Times reported that Russia had used new hypersonic missiles in a massive missile attack on Ukraine. Such missiles are more effective in evading conventional Ukrainian anti-missile defences that had previously proved useful against Russia's conventional, non-hypersonic missile systems.[401]

The strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure were part of Russia's 'Strategic Operation for the Destruction of Critically Important Targets' (SODCIT) military doctrine, said the UK Defense Ministry, intended to demoralize the population and forcing the Ukrainian leadership to capitulate.[402] According to the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), "Russian strikes had cumulatively destroyed 9 gigawatts (GW) of Ukraine's domestic power generation by mid-June 2024. Peak consumption during the winter of 2023 was 18 GW, which means that half of Ukraine's production capacity has been destroyed."[403]

On 8 July 2024, Russia used a Kh-101 missile[404] to kill at least two people and injure at least 16 people at the Okhmatdyt Children's Hospital in Kyiv.[405][406][407] Also hit the same night were facilities in Pokrovsk and Kryvyi Rih.[408] At least 20 civilians were killed in Kyiv that night.[409]

Naval blockade and engagements