Running the gauntlet

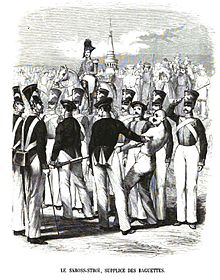

To run the gauntlet means to take part in a form of corporal punishment in which the party judged guilty is forced to run between two rows of soldiers, who strike out and attack them with sticks or other weapons.

Metaphorically, this expression is also used to convey a public trial that one must overcome.

Etymology and spelling

[edit]The word gauntlet originates from Swedish gatlopp, from gata 'lane' and lopp 'course, running'.[1] It was borrowed into English in the 17th century, probably from English and Swedish soldiers fighting in the Protestant armies during the Thirty Years' War. The punishment itself was rarely used in the Swedish Army during the reign of the monarch Gustav III in the 1770s and was abolished in the Swedish Army in 1851.[2][3][4][5][6]

The word in English was originally spelled gantelope or gantlope,[7] but soon its pronunciation was influenced by the unrelated word gauntlet, meaning an armored glove, derived from the French: gantelet.[1] The spelling changed with the pronunciation. Both senses of gauntlet had the variant spelling gantlet.[1] For the punishment, the spelling gantlet is preferred in American English usage guides by Bryan Garner and Robert Hartwell Fiske[8][9] and is listed as a variant spelling of gauntlet by American dictionaries.[1][10] British dictionaries label gantlet as American.[11][12]

Usage and severity

[edit]

A naval version of the gauntlet was historically used in the Royal Navy as a punishment for minor offences such as leaving the crew berths in an unsanitary state, or failing to return on time from leave. The condemned was ordered to make a prescribed number of circuits around the ship's deck, while his shipmates struck him with improvised versions of the cat o' nine tails.[13] Runs of the gauntlet could also be preceded by a dozen lashes from the boatswain's cat o' nine tails, so that any subsequent blows from the crew would aggravate the lacerations on his back.[14] The effectiveness of the punishment would somewhat depend on the popularity of the sailor being punished, and the seriousness of the offence. In 1760, Francis Lanyon, a seaman aboard the guardship HMS Royal George, was sentenced to three runs of the gauntlet, for failing to return from leave. The crew clearly disagreed with the punishment, as the ship's lieutenant later recorded that Lanyon received no substantial injury from the process.[13] The naval punishment of running the gauntlet was abolished by Admiralty Order in 1806.[14]

In the early records of the Dutch colonial settlement of New Amsterdam appears a detailed description of running the "Gantlope/Gantloppe" as a punishment for the "Court Martial of Melchior Claes" (a soldier). It states "... The Court Marshall doe adjudge that hee shall run the Gantlope once the length of the fort, where according to the Custome of that punishment the souldyers shall have switches delivered to them with which they shall strike him as he passes through them stript to the wast, and at the fort gate the Marshall is to receive him and there to kick him out of the Garrison as a cashiered person where hee is no more to returne ..."[15]

Native American usage

[edit]

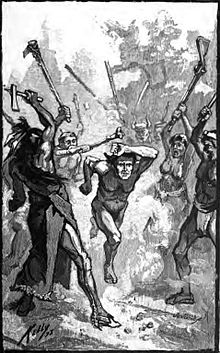

Several Native American tribes of the Eastern Woodlands cultural area forced prisoners to run the gauntlet (see Captives in American Indian Wars).[citation needed] The Jesuit Isaac Jogues was subject to this treatment while a prisoner of the Iroquois in 1641. He described the ordeal in a letter that appears in the book The Jesuit Martyrs of North America: "Before arriving (at the Iroquois Village) we met the young men of the country, in a line armed with sticks...", and he and his fellow Frenchmen were made to walk slowly past them "for the sake of giving time to anyone who struck us."[16]

In 1755, Charles Stuart was taken prisoner by Lenape warriors during the Great Cove massacre, and upon arriving at the village of Kittanning, was forced to run the gauntlet. He provides a description of the practice:

on Entring into the Town we were obliged to Pass Between Two Rows of Indians Containing abt 100 on Each Side, who were arm'd with various kind of Weapons such as Axes Tomhawks Cutlasses Hoop Poles, Pieces of Wood &c, But they did not strike with the Axes, and only Used the Heads and Handles of their Tomhawks, But used the Blades of the Cutlasses, tho' not with so much Severity as To Kill. I had however the Misfortune to receive a Blow on the Side of my Forehead With one of them wch Cut me To the Bone, & a Billet of Wood Strikeing on the Head abt the Same time, Between Both I was Knock'd down to the Ground - It was, only the more elderly People both, Male and Female wch rece'd this Useage - the young prisioners of Both Sexes Escaped without it.[17]: 66

Many years before he became a hero of the American Revolution at the Battle of Bennington, John Stark was captured by natives and forced to run a gauntlet. Knowing what was about to happen Stark stunned them by grabbing the weapon away from the first person about to strike him and proceeded to attack the warrior with it. The warriors and the chief were so surprised by this that they stopped the gauntlet and adopted him into their tribe. He was later ransomed along with Amos Eastman for $163 and returned home.[18]

Modern use

[edit]Fitness trail in communist Poland

[edit]During the days of the Polish People’s Republic, the communist authorities forced political dissidents, criminals, protestors, and prisoners through a gauntlet-like process, which they called the ścieżka zdrowia (literally 'health path', but idiomatically used to mean early fitness trails).

In KOR, A History of the Worker's Defense Committee in Poland, 1976–1981, Jan Józef Lipski documents the experience of one such criminal during the June 1976 protests:

On the first day I walked the "path of health" on the way from a truck to the police van, about 50 metres. They ordered me to walk slowly so that each one could hit me. They beat me with fists, clubs, boots. At the very end, I fell down. I couldn't get up again under the hail of clubs... A "path of health" from the van to the second floor... When they took us to get haircuts – another "path of health" some 40 metres long, from the door of the room all the way to the car... Yet another 10 metres in the corridor leading to the table... Then, a "path of health" (10 metres) to cell number nine... to the court in a prison truck; of course another "path of health"... then again a "path" from prison to prison. I survived another "path of health" in the morning when they took me to Kielce.

— Waldemar Michalski, [19]

Military custom

[edit]Similar practices are used in other initiations and rites of passage, as on pollywogs (those passing the equator for the first time [20] includes a paddling version)

In one Tailhook Association convention for Navy and Marine Corps pilots, female participants were allegedly forced to run the gauntlet in a hotel hallway as male participants fondled them.[21]

Sports

[edit]

In certain team sports, such as lacrosse and ice hockey, the gauntlet is a common name for a type of drill whereby players are blocked or checked by the entire team in sequence.[22]

In Brazilian jiu-jitsu, when a student is promoted to their next coloured belt, they are sometimes required to run between two rows of their fellow students, who strike them with their own belts.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "gaunt·let2 also gant·let". American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". 2011-01-04. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 2004, "Gantelope"

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 2004, "Gauntlet"

- ^ Word Origins, 2005, A&C Black, "Gauntlet"

- ^ Word Histories and Mysteries, 2004, Houghton Mifflin, "Gauntlet"

- ^ Maddox, Maeve. "Running the Gamut and Running the Gauntlet". www.dailywritingtips.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Garner, Bryan (2009). "gantlet; gantlope". Garner's Modern American Usage (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0199888771.

- ^ Fiske, Robert Hartwell (2006). "Gauntlet". The Dictionary of Disagreeable English (Deluxe ed.).

- ^ "gantlet". Merrian-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ "gantlet". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ "gauntlet2". British & World English dictionary. Oxford dictionaries. Archived from the original on September 29, 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ a b Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0870219871.

- ^ a b The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, Peter Kemp ed., 1976 ISBN 0-586-08308-1

- ^ Peter R. Christoph, ed., New York Historical Manuscripts: English, Vol. 22, "Administrative Papers of Governors Richard Nicolls and Francis Lovelace, 1664–1673," (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1980), pp 163–64. 22:123 [Minutes of the Court Martial of Melchior Claes, accused of theft] ... held at Fort James the 28th day of December 1671

- ^ Wynne, John Joseph (1925). The Jesuit Martyrs of North America. Universal Knowledge Foundation. p. 163.

- ^ Beverly W. Bond, "The Captivity of Charles Stuart, 1755-57," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Jun., 1926, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 58-81

- ^ Stark, Caleb; Stark, John (1860). Memoir and official correspondence of Gen. John Stark, with notices of several other officers of the Revolution. Also, a biography of Capt. Phinehas Stevens and of Col. Robert Rogers, with an account of his services in America during the "Seven Years' War.". Harvard University. Concord, G.P. Lyon.

- ^ KOR, A history of the Worker's Defense Committee in Poland, 1976–1981, by Jan Jósef Lipski, Translated by Olga Amsterdamska and Gene M. Moore, University of California Press, 1985, page 35

- ^ The U. S. S. West Virginia: Crossing the Equator, West Virginia Division of Culture and History

- ^ Office of the Inspector General (31 December 2003). The Tailhook Report. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-312-30212-2. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- ^ "The Drill – Running the Gauntlet". CBC. Archived from the original on 2013-07-25. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- ^ "The Gauntlet (Belt Whipping)". BJJ Heroes. Retrieved 2018-07-27.