Roxelana

| Hürrem Sultan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Titian titled La Sultana Rossa, c. 1550 | |||||

| Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Imperial Consort) | |||||

| Tenure | c. 1533 – 15 April 1558 | ||||

| Predecessor | position established | ||||

| Successor | Nurbanu Sultan | ||||

| Born | Aleksandra Anastazja Lisowska c. 1504 Rohatyn, Ruthenia, Kingdom of Poland (now Ukraine) | ||||

| Died | 15 April 1558 (aged 53–54) Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire (now Istanbul, Turkey) | ||||

| Burial | Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman (by marriage) | ||||

| Father | Hawryło Lisowski[1] | ||||

| Mother | Leksandra Lisowska[1] | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam, previously Eastern Orthodox Christian | ||||

Hürrem Sultan (Turkish: [hyɾˈɾæm suɫˈtan]; Ottoman Turkish: خرّم سلطان, "the joyful one"; c. 1504 – 15 April 1558), also known as Roxelana (Ukrainian: Роксолана, romanized: Roksolana), was the chief consort, Haseki Sultan and legal wife of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She became one of the most powerful and influential women in Ottoman history,[2] and as well a prominent figure during the period known as the Sultanate of Women.

Born in Ruthenia (then an eastern region of the Kingdom of Poland, now Rohatyn, Ukraine) to a Ruthenian Orthodox family, she was captured by Crimean Tatars during a slave raid and eventually taken via the Crimean trade to Constantinople, the Ottoman capital.[3]

She entered the Imperial Harem where her name was changed to Hürrem, rose through the ranks and became the favourite concubine of Sultan Suleiman. Breaking Ottoman tradition, he married Hürrem, making her his legal wife. Sultans had previously married only foreign freeborn noblewomen. She was the first imperial consort to receive the title, created for her, to Haseki Sultan. Hürrem remained in the sultan's court for the rest of her life, enjoying a close relationship with her husband, and having six children with him, including the future sultan, Selim II, which makes Hürrem an ancestor of all following sultans and currently living members of the Ottoman dynasty. Of Hürrem's six children, five were male, breaking the Ottoman custom according to which each concubine could only give the Sultan one male child, to maintain a balance of power between the various consorts. However, not only did Hürrem bear more children to the sultan after the birth of her first son in 1521, but she was also the mother of all of Suleiman's children born after her entry into the harem at the beginning of his reign.

Hürrem eventually achieved power, influencing the politics of the Ottoman Empire. Through her husband, she played an active role in affairs of the state. She probably acted as the sultan's advisor, wrote diplomatic letters to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland (r. 1548–1572) and patronized major public works (including the Haseki Sultan Complex and the Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse). She died in 1558, in Constantinople and was buried in a mausoleum within the Süleymaniye Mosque complex.

Names

[edit]Leslie P. Peirce has written that her birth name may have been either Aleksandra or Anastazja Lisowska. Among the Ottomans, she was known mainly as Haseki Hürrem Sultan or Hürrem Haseki Sultan. Hürrem or Khurrem (Persian: خرم) means "the joyful one" in Persian. The name Roxalane derives from Roksolanes, which was the generic term used by the Ottomans to describe girls from Podolia and Galicia who were taken in slave raids.[4][5]

Origin

[edit]Sources are mostly in agreement to indicate that Hürrem was originally from Ruthenia, which was then part of the Polish Crown.[6] She was born in the town of Rohatyn 68 km (42 mi) southeast of Lwów (Lviv) , a major city of the Ruthenian Voivodeship of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland,[5][7] in what is now Ukraine. Her native language was Ruthenian, the precursor to modern Ukrainian.[8] According to late 16th-century and early 17th-century sources, such as the Polish poet Samuel Twardowski (died 1661), who researched the subject in Turkey, Hürrem was seemingly born to a man named Hawrylo Lisovski, who was an Orthodox priest of Ruthenian origin, and his wife Leksandra.[7][9][10]

During the reign of Selim I,[11] which was some time between 1512 and 1520, Crimean Tatars kidnapped her during one of their Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe. The Tatars may have first taken her to the Crimean city of Kaffa, a major centre of the Ottoman slave trade, before she was taken to Constantinople.[7][9][10] Shaykh Qutb al-Din al-Nahrawali, a Meccan religious figure, who visited Constantinople in 1558, noted in his memoirs that she had been a servant in the household of Hançerli Hanzade Fatma Zeynep Sultan, daughter of Şehzade Mahmud, one of the sons of Sultan Bayezid II, who gifted her to Suleiman when he rose to the throne.[12]

In Constantinople, Hafsa Sultan, mother of Suleiman, selected Hürrem as a gift for her son. Other versions claim that it was Suleiman's confidant and future Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha who introduced Hürrem into his harem. Hürrem later managed to become the first Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman imperial harem.[6] Michalo Lituanus wrote in the 16th century that "the most beloved wife of the present Turkish emperor – mother of his first [son] who will govern after him, was kidnapped from our land".[i][13]

European ambassadors of that period called her Roxelana, meaning "Ruthenian woman"[14] or "the Ruthenian one" for her alleged Ruthenian origins.[15] She is the sultan's consort with the most portraits in her name in the Ottoman Empire, though the portraits are imaginary depictions by painters.[16]

Relationship with Suleiman

[edit]

Hürrem Sultan probably entered the harem around sixteen years of age. The precise year that she entered the harem is unknown, but it believe that she became Suleiman's concubine around the time he became sultan in 1520, because their first child was born in 1521.[17]

Hürrem's unprecedented rise from harem slave to Suleiman's legal wife attracted jealousy and disfavor not only from her rivals in the harem, but also from the general populace.[6] She soon became Suleiman's most prominent consort beside Gülbahar Mahidevran Hatun and their relationship was monogamous. While the exact dates for the births of her children are disputed, there is academic consensus that the births of her first five children —Şehzade Mehmed, Mihrimah Sultan, Selim II, Şehzade Abdullah and Şehzade Bayezid – occurred quickly over the next five to six years.[17]: 130 Suleiman and Hürrem's last child, Şehzade Cihangir was born later, in 1531, but by that time Hürrem had given birth to enough healthy sons to secure the future of the Ottoman dynasty.[17]: 131

Hürrem was allowed to give birth to more than one son which was a stark violation of the old imperial harem principle, "one concubine mother – one son," which was designed to prevent both the mother's influence over the sultan and the feuds of the blood brothers for the throne.[13] She was to bear the majority of Suleiman's children. Hürrem gave birth to her first son Mehmed in 1521 (who died in 1543) and then to four more sons, destroying Mahidevran's status as the mother of the sultan's only surviving son.[18]

Suleiman's mother, Hafsa Sultan, partially suppressed the rivalry between the two women.[19] According to Bernardo Navagero's report, as a result of the bitter rivalry a fight between the two women broke out, with Mahidevran beating Hürrem, which angered Suleiman.[20] According to Necdet Sakaoğlu, a Turkish historian, these accusations were not truthful. After the death of Suleiman's mother Hafsa Sultan in 1534, Hürrem's influence in the palace increased, and she took over the ruling of the harem.[21] Hürrem became the only partner of the ruler and received the title of Haseki, which means the favorite. When Suleiman freed and married her, or in the years before, she became the Haseki Sultan (adding the word sultan to a woman's name or title indicated that she was a part of the dynasty).[22]

Around 1533,[23] Suleiman married Hürrem[13] in a magnificent formal ceremony. Never before had a former slave been elevated to the status of the sultan's lawful spouse, a development which astonished observers in the palace and in the city.[24] The wedding celebration took place in 1534.[23]

Hürrem became the first consort to receive the title Haseki Sultan.[25] This title, used for a century, reflected the great power of imperial consorts (most of them were former slaves) in the Ottoman court, elevating their status higher than Ottoman princesses. In this case, Suleiman not only broke the old custom, but began a new tradition for the future Ottoman sultans: to marry in a formal ceremony and to give their consorts significant influence on the court, especially in matters of succession. Hürrem's salary was 2,000 akçe a day, making her one of the highest-paid Ottoman Imperial women. After the wedding, the idea circulated that the sultan had limited his autonomy and was dominated and controlled by his wife.[26] Also, in Ottoman society, mothers played more influential roles in their sons' educations and in guiding their careers.[26]

After the death of Suleiman's mother, Hafsa Sultan, in 1534, Hürrem became Suleiman's most trusted news source. In one of her letters to Suleiman, she informs him about the situation of the plague in the capital. She wrote, "My dearest Sultan! If you ask about Istanbul, the city still suffers from the plague; however, it is not like the previous one. God willing, it will go away as soon as you return to the city. Our ancestors said that the plague goes away once the trees shed their leaves in autumn."[27] Later, Hürrem became the first woman to remain in the sultan's court for the duration of her life. In the Ottoman imperial family tradition, a sultan's consort was to remain in the harem only until her son came of age (around 16 or 17), after which he would be sent away from the capital to govern a faraway province, and his mother would follow him. This tradition was called Sancak Beyliği. The consorts were never to return to Constantinople unless their sons succeeded to the throne.[28] In defiance of this age-old custom, Hürrem stayed behind in the harem, even after her sons went to govern the empire's remote provinces.

Moreover, remaining in Costantinople, she moved out of the harem located in the Old Palace (Eski Saray) and permanently moved into the Topkapı Palace after a fire destroyed the old harem. Some sources say she moved to Topkapı, not because of the fire, but as a result of her marriage to Suleiman. Either way, this was another significant break from established customs, as Mehmed the Conqueror had specifically issued a decree to the effect that no women would be allowed to reside in the same building where government affairs were conducted.[17]: 131 After Hürrem resided at Topkapı it became known as the New Palace (saray-ı jedid).[29]

She wrote many love letters to Suleiman when he was away for campaigns. In one of her letters, she wrote:

- "After I put my head on the ground and kiss the soil that your blessed feet step upon, my nation's sun and wealth my sultan, if you ask about me, your servant who has caught fire from the zeal of missing you, I am like the one whose liver (in this case, meaning heart) has been broiled; whose chest has been ruined; whose eyes are filled with tears, who cannot distinguish anymore between night and day; who has fallen into the sea of yearning; desperate, mad with your love; in a worse situation than Ferhat and Majnun, this passionate love of yours, your slave, is burning because I have been separated from you. Like a nightingale, whose sighs and cries for help do not cease, I am in such a state due to being away from you. I would pray to Allah to not afflict this pain even upon your enemies. My dearest sultan! As it has been one-and-a-half months since I last heard from you, Allah knows that I have been crying night and day waiting for you to come back home. While I was crying without knowing what to do, the one and only Allah allowed me to receive good news from you. Once I heard the news, Allah knows, I came to life once more since I had died while waiting for you.[27]

Under his pen name, Muhibbi, Sultan Suleiman composed this poem for Hürrem Sultan:

"Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight.

My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence, my Sultan, my one and only love.

The most beautiful among the beautiful...

My springtime, my merry faced love, my daytime, my sweetheart, laughing leaf...

My plants, my sweet, my rose, the one only who does not distress me in this world...

My Istanbul, my Caraman, the earth of my Anatolia

My Badakhshan, my Baghdad and Khorasan

My woman of the beautiful hair, my love of the slanted brow, my love of eyes full of mischief...

I'll sing your praises always

I, lover of the tormented heart, Muhibbi of the eyes full of tears, I am happy."[30]

State affairs

[edit]Hürrem Sultan is known as the first woman in Ottoman history to concern herself with state affairs. Hürrem Sultan was able to achieve what no concubine before her had achieved. She officially became Suleiman's wife, and although there were no laws at the time prohibiting marriages between sultans and concubines, the entire Ottoman court was against the marriage. Suleiman had not respected traditions. The wedding probably took place in June 1533, although the exact date of this event is still unknown. Hürrem's position was unique, as was the title of Haseki.

Suleiman spent most of his time on military campaigns, consequently he needed someone reliable to provide him with information about the situation in the palace: he chose Hürrem Sultan. The letters written by Suleiman to Hürrem have been preserved; from these emerges the great feeling of love that the sultan felt for Roxelana and the lack of her that he felt of her.

Historical scholars note that, in the early stages of his reign, Suleiman relied on correspondence, not with Haseki, but with his mother, as Hürrem did not know the language well enough. In fact, the first letters to the sultan written by Hürrem contain bureaucratic language, which suggests that they were written with the help of the court scribe. In her letters to her husband, she conveyed the greetings of the statesmen and the Sheikh-ul-Islam of Istanbul, and talked about the problems in Istanbul.[31]

Hürrem was one of the most educated women in the world at that time and she played an important role in the political life of the Ottoman Empire. Thanks to her intelligence, she acted as Suleiman's chief adviser on matters of state, and seems to have had an influence upon foreign policy and international politics. She freely communicated with the ambassadors of European countries, corresponded with the rulers of Venice and Persia, and stood by Suleiman at receptions and banquets. She imprinted her seal and watched the council meetings through a wire mesh window. With many other revolutionary movements like these, she had started an era in Ottoman Empire called the Sultanate of Women.[32] Hürrem's Influence over Suleiman was so significant that rumors circulated around the Ottoman court that the sultan had been bewitched.[6]

Her influence with Suleiman made her one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history and in the world at that time. Even as a consort, her power was comparable with the most powerful woman of the Imperial Harem, who by tradition was the sultan's mother or valide sultan. Hürrem Sultan was the most powerful Haseki Sultan, because she was the only one who obtained the role and power of a Valide Sultan when she legally married the Sultan. For this reason, she has become a controversial figure in Ottoman history – subject to allegations of plotting against and manipulating her political rivals.

Controversial figure

[edit]

Hürrem's influence in state affairs not only made her one of the most influential women, but also a controversial figure in Ottoman history, especially in her rivalry with Mahidevran and her son Şehzade Mustafa, and the grand viziers Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha and Kara Ahmed Pasha.

Hürrem and Mahidevran had given birth to Suleiman's six şehzades (Ottoman princes): Mustafa, Mehmed, Selim, Abdüllah (died at three), Bayezid, and Cihangir. Of these, Mahidevran's son Mustafa was the eldest and preceded Hürrem's children in the order of succession. Traditionally, when a new sultan rose to power, he would order all of his brothers killed in order to ensure there was no power struggle. This practice was called kardeş katliamı, literally "fraternal massacring".[33]

Mustafa was supported by Ibrahim Pasha, who became Suleiman's grand vizier in 1523. Hürrem has usually been held at least partly responsible for the intrigues in nominating a successor.[17]: 132 Although she was Suleiman's wife, she exercised no official public role. This did not, however, prevent Hürrem from wielding powerful political influence. Since the empire lacked, until the reign of Ahmed I (1603–1617), any formal means of nominating a successor, successions usually involved the death of competing princes in order to avert civil unrest and rebellions. In attempting to avoid the execution of her sons, Hürrem used her influence to eliminate those who supported Mustafa's accession to the throne.[34]

A skilled commander of Suleiman's army, Ibrahim eventually fell from grace after an imprudence committed during a campaign against the Persian Safavid empire during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), when he awarded himself a title including the word "Sultan". Another conflict occurred when Ibrahim and his former mentor, İskender Çelebi, repeatedly clashed over military leadership and positions during the Safavid war. These incidents launched a series of events which culminated in his execution in 1536 by Suleiman's order. It is believed that Hürrem's influence contributed to Suleiman's decision.[35] After three other grand viziers in eight years, Suleiman selected Hürrem's son-in-law, Damat Rüstem Pasha, husband of Mihrimah, to become the grand vizier. Scholars have wondered if Hürrem's alliance with Mihrimah Sultan and Rüstem Pasha helped secure the throne for one of Hürrem's sons.[17]: 132

Many years later, towards the end of Suleiman's long reign, the rivalry between his sons became evident. Mustafa was later accused of causing unrest. During the campaign against Safavid Persia in 1553, because of fear of rebellion, Suleiman ordered the execution of Mustafa. According to a source he was executed that very year on charges of planning to dethrone his father; his guilt for the treason of which he was accused remains neither proven nor disproven.[36] It is also rumored that Hürrem Sultan conspired against Mustafa with the help of her daughter and son-in-law Rustem Pasha; they wanted to portray Mustafa as a traitor who secretly contacted the Shah of Iran. Acting on Hürrem Sultan's orders, Rustem Pasha had engraved Mustafa's seal and sent a letter seemingly written by him to Shah Tahmasb I, and then sent the shah's response to Suleiman.[ii][citation needed] After the death of Mustafa, Mahidevran lost her status in the palace as the mother of the heir apparent and moved to Bursa.[18] She did not spend her last years in poverty, as Hürrem's son, Selim II, the new sultan after 1566, put her on a lavish salary.[36] Her rehabilitation had been possible after the death of Hürrem in 1558.[36] Cihangir, Hürrem's youngest child, allegedly died of grief a few months after of his half-brother's murder.[37]

Although the stories about Hürrem's role in executions of Ibrahim, Mustafa, and Kara Ahmed are very popular, actually none of them are based on first-hand sources. All other depictions of Hürrem, starting with comments by sixteenth and seventeenth-century Ottoman historians as well as by European diplomats, observers, and travellers, are highly derivative and speculative in nature. Because none of these people – neither Ottomans nor foreign visitors – were permitted into the inner circle of the imperial harem, which was surrounded by multiple walls, they largely relied on the testimony of the servants or courtiers or on the popular gossip circulating around Constantinople.[13]

Even the reports of the Venetian ambassadors (baili) at Suleiman's court, the most extensive and objective first-hand Western source on Hürrem to date, were often filled with the authors' own interpretations of the harem rumours. Most other sixteenth-century Western sources on Hürrem, which are considered highly authoritative today – such as Turcicae epistolae (English: The Turkish Letters) of Ogier de Busbecq, the Emissary of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I at the Porte between 1554 and 1562; the account of the murder of Şehzade Mustafa by Nicholas de Moffan; the historical chronicles on Turkey by Paolo Giovio; and the travel narrative by Luidgi Bassano – derived from hearsay.[13]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Hürrem acted as Suleiman's advisor on matters of state, and seems to have had an influence upon foreign policy and on international politics. Two of her letters to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland (reigned 1548–1572) have survived, and during her lifetime the Ottoman Empire generally had peaceful relations with the Polish state within a Polish–Ottoman alliance.

In her first short letter to Sigismund II, Hürrem expresses her highest joy and congratulations to the new king on the occasion of his ascension to the Polish throne after the death of his father Sigismund I the Old in 1548. There was a seal on the back of the letter. For the first and only time in the Ottoman Empire, a female sultan exchanged letters with a king. After that, although Hürrem's successor Nurbanu Sultan and her successor Safiye Sultan exchanged letters with queens, there is no other example of a sultana who personally contacted a king other than Hürrem Sultan.[ii][citation needed] She pleads with the King to trust her envoy Hassan Ağa, who verbally delivered another message from her. Some sentences of the letter sent to Warsaw by Haseki Sultan her are as follows:

"We learned that you became the king of Poland after your father passed away. Allah knows the truth of everything; we were very happy and pleased. Light came to our hearts, joy and happiness came to our hearts. We wish your reign to be auspicious, fruitful and long-lasting. The command belongs to Allah Almighty; we advise you to act in accordance with the decrees (orders) of Allah Almighty..."

In her second letter to Sigismund Augustus, written in response to his letter, Hürrem expresses in superlative terms her joy at hearing that the king is in good health and that he sends assurances of his sincere friendliness and attachment towards Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She quotes the sultan as saying, "with the old king we were like brothers, and if it pleases the All-Merciful God, with this king we will be as father and son." With this letter, Hurrem sent Sigismund II the gift of two pairs of linen shirts and pants, some belts, six handkerchiefs, and a hand-towel, with a promise to send a special linen robe in the future.

There are reasons to believe that these two letters were more than just diplomatic gestures, and that Suleiman's references to brotherly or fatherly feelings were not a mere tribute to political expediency. The letters also suggest Hürrem's strong desire to establish personal contact with the king. In his 1551 letter to Sigismund II concerning the embassy of Piotr Opaliński, Suleiman wrote that the Ambassador had seen "Your sister and my wife." Whether this phrase refers to a warm friendship between the Polish King and Ottoman Haseki, or whether it suggests a closer relation, the degree of their intimacy definitely points to a special link between the two states at the time.[13]

Some of her embroideries, or at least made under her supervision, have come down to us, such as those given in 1547 to Tahmasp I Shah of Iran and in 1549 to Sigismund II Augustus of Poland . Esther Handali acted as her secretary and intermediary on several occasions.

Charities

[edit]

Aside from her political concerns, Hürrem engaged in several major works of public buildings, from Makkah to Jerusalem (Al-Quds), perhaps modelling her charitable foundations in part after the caliph Harun al-Rashid's consort Zubaida.

Among her first foundations were a mosque, two Quranic schools (madrassa), a fountain, and a women's hospital near the women's slave market (Avret Pazary) in Constantinople (Haseki Sultan Complex). It was the first complex constructed in Constantinople by Mimar Sinan in his new position as the chief imperial architect. The mosque was completed in 1538–39, the madrasa was completed a year later in 1539–40 and the soup-kitchen in 1540–41. The hospital was not completed until 1550–51.[38]

She built mosque complexes in Adrianopole and Ankara. She commissioned a bath, the Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse, to serve the community of worshippers in the nearby Hagia Sophia. It was Constructed in 1556 and was designed by Mimar Sinan[38]. In Jerusalem she established the Haseki Sultan Imaret in 1552, a public soup kitchen to feed the poor,[39][40][41] which was said to have fed at least 500 people twice a day.[42] She built a public soup kitchen in Makkah.[13]

In a foundation charter (Vakfiye) signed by a judge (Qādī ) and witnesses, not only were the buildings concerned listed, but their long-term maintenance was also ensured.[43][41] Such documented maintenance could also refer to existing foundations of her own or those of other donors. Hurrem's foundation charters from 1540 and 1551 record donations for the maintenance of long-established dervish convents in various Istanbul districts.[44][45]

She had a Kira who acted as her secretary and intermediary on several occasions, although the identity of the kira is uncertain (it may have been Strongilah.[46]).

Death

[edit]

Hürrem died on 15 April 1558 due to an unknown illness. In the last years of her life she was in very poor health. It is said that the Sultan, in order not to disturb the peace of his wife during the course of her illness, ordered all the musical instruments in the palace to be burned. He did not leave Hurrem's bed until the last day, when she died. The farewell dedications written by the Sultan to Haseki after her death, which have been preserved to the present day, demonstrated Suleiman's love for Hürrem.

She was buried in a domed mausoleum (türbe) decorated in exquisite Iznik tiles depicting the garden of paradise, perhaps in homage to her smiling and joyful nature.[47] Her mausoleum is adjacent to Suleiman's, a more somber, domed structure, at the courtyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque.

Personality

[edit]Hürrem's contemporaries describe her as a woman who was strikingly good-looking, and different from everybody else because of her red hair.[48] Hürrem was also intelligent and had a pleasant personality. Her love of poetry is considered one of the reasons behind her being heavily favoured by Suleiman, who was a great admirer of poetry.[48]

Hürrem is known to have been very generous to the poor. She built numerous mosques, madrasahs, hammams, and resting places for pilgrims travelling to the Islamic holy city of Makkah. Her greatest philanthropical work was the Great Waqf of AlQuds, a large soup kitchen in Jerusalem that fed the poor.[49]

It is believed that Hürrem was a cunning, manipulative and stony-hearted woman who would execute anyone who stood in her way. However, her philanthropy is in contrast to this as she cared for the poor. Prominent Ukrainian writer Pavlo Zahrebelny describes Hürrem as "an intelligent, kind, understanding, openhearted, candid, talented, generous, emotional and grateful woman who cares about the soul rather than the body; who is not carried away with ordinary glimmers such as money, prone to science and art; in short, a perfect woman."[50]

Legacy

[edit]Hürrem is well-known both in modern Turkey and in the West, and is the subject of many artistic works. In 1561, three years after her death, the French author Gabriel Bounin wrote a tragedy titled La Soltane.[51] This tragedy marks the first time the Ottomans were introduced on stage in France.[52] She has inspired paintings, musical works (including Joseph Haydn's Symphony No. 63), an opera by Denys Sichynsky, a ballet, plays, and several novels written mainly in Russian and Ukrainian, but also in English, French, German and Polish.

In early modern Spain, she appears or is alluded to in works by Quevedo and other writers as well as in a number of plays by Lope de Vega. In a play entitled The Holy League, Titian appears on stage at the Venetian Senate, and stating that he has just come from visiting the Sultan, displays his painting of Sultana Rossa or Roxelana.[53]

In 2007, Muslims in Mariupol, a port city in Ukraine opened a mosque to honour Roxelana.[54]

In the 2003 TV miniseries, Hürrem Sultan, she was played by Turkish actress and singer Gülben Ergen. In the 2011–2014 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, Hürrem Sultan is portrayed by Turkish-German actress Meryem Uzerli from seasons one to three. For the series' last season, she is portrayed by Turkish actress Vahide Perçin. Hürrem is portrayed by Megan Gale in the 2022 movie Three Thousand Years of Longing.

In 2019, a mention of a Russian origin for Hürrem was removed from the visitor panel near her tomb at the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul at the request of the Ukrainian embassy in Turkey.[55]

Visual tradition

[edit]

Although male European artists were denied access to Hürrem in the harem, there are many Renaissance paintings of the famous sultana. Scholars thus agree that European artists created a visual identity for Ottoman women that was largely imagined.[56] The artists Titian, Melchior Lorich and Sebald Beham were all influential in creating a visual representation of Hürrem. Images of the chief consort emphasized her beauty and wealth, and she is almost always depicted with elaborate headwear.

The Venetian painter Titian is reputed to have painted Hürrem in 1550. Although he never visited Constantinople, he either imagined her appearance or had a sketch of her. In a letter to Philip II of Spain, the painter claims to have sent him a copy of this "Queen of Persia" in 1552. The Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida, purchased the original or a copy around 1930.[57] Titian's painting of Hürrem is very similar to his portrait of her daughter, Mihrimah Sultan.[56]

Issue

[edit]

With Suleiman, she had five sons and one daughter:

- Şehzade Mehmed (1521, Old Palace, Constantinople – 7 November 1543, Manisa Palace, Manisa, buried in Şehzade Mosque, Constantinople). Hürrem's firstborn. He became the sanjak-bey of Manisa and presumptive heir to the throne from 1541 until his death.

- Mihrimah Sultan (1522, Old Palace, Constantinople – 25 January 1578, Constantinople, buried in Suleiman I Mausoleum, Süleymaniye Mosque). Hürrem's only daughter. She was married to Rüstem Pasha, later Ottoman Grand Vizier, on 26 November 1539, and had a daughter and at least a son.

- Selim II (28 May 1524, Old Palace, Constantinople – 15 December 1574, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque). He was sanjak-bey of Karaman, then of Manisa after Mehmed's death and later governor of Konya and Kütahya. Suleiman's only son that survived after him, he ascended to the throne on 7 September 1566 as Selim II.

- Şehzade Abdullah (c. 1525, Old Palace, Constantinople – c. 1528, Old Palace, Constantinople, buried in Yavuz Selim Mosque).[58][59]

- Şehzade Bayezid (1527, Old Palace, Constantinople – 25 September 1561, Qazvin, Safavid Empire, buried in Melik-i Acem Türbe, Sivas). He was governor of Karaman, Kütahya and later Amasya. He rebelled against his father for the throne and was, for this, executed by him, together with his sons.[59]

- Şehzade Cihangir (1531, Old Palace, Constantinople – 27 November 1553, Aleppo, buried in Şehzade Mosque, Istanbul). Born with kyphosis and in poor health, for this he was judged unfit as an heir and was therefore not assigned any province to govern. For the same reason, he was not allowed to have concubines or father children.

Gallery

[edit]-

18th century portrait of Hürrem Sultan kept at Topkapı Palace.

-

A portrait of Hürrem in the British Royal Collection, c. 1600–70

-

A painting of Hürrem Sultan by a follower of Titian, 16th century

-

Hürrem and Süleyman the Magnificent by the German baroque painter Anton Hickel, (1780)

-

Engraving by Johann Theodor de Bry, (1596)

-

16th century oil on wood painting of Hürrem Sultan

-

Tribute to Hürrem on 1997 Ukrainian postage stamp

-

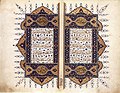

Serlevha (illuminated frontispiece) from the Endowment Charter (Waqfiyya) pertaining to the architectural complex commissioned by Hürrem Sultan in the Aksaray district of Istanbul. 1540. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts

-

The Hagia Sophia Hürrem Sultan Bathhouse built in 1556

In popular culture

[edit]- She was portrayed by German–Turkish actress Meryem Uzerli as young adult and adult Hürrem, and by Turkish actress Vahide Perçin as middle age Hürrem in the television series Muhteşem Yüzyıl.

- She was portrayed by Turkish actress Gülben Ergen in the television mini-series Hürrem Sultan.

- She was portrayed by Australian actress Megan Gale in the movie Three Thousand Years of Longing.

- The novel Roxelana şi Soliman by Romanian author Vintilă Corbul is a fictionalized account of the love story between Hürrem, whose origin is identified as Polish noblewoman Alexandra Lisowska, and Suleiman the Magnificent.

See also

[edit]- Ottoman dynasty

- Ottoman family tree

- List of mothers of the Ottoman sultans

- List of consorts of the Ottoman sultans

- Haseki Sultan Complex, Fatih, Istanbul

- Hagia Sophia Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse, Fatih, Istanbul

- Haseki Sultan Imaret, Jerusalem

- Suleiman the Magnificent

- Sultanate of Women

Notes

[edit]- ^ The title of his book is De moribus tartarorum, lituanorum et moscorum or On the customs of Tatars, Lithuanians and Moscovians.

- ^ a b Content in this edit is translated from the existing Turkish Wikipedia article at tr :Hürrem Sultan; see its history for attribution.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dr Galina I Yermolenko (2013). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culturea. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-409-47611-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017.

- ^ Galina Yermolenko (2005). Roxolana: The Greatest Empresse of the East. Muslim World, Volume 95, Issue 2, pp. 231–248.

- ^ "2 Reasons Why Hurrem Sultan and Empress Ki were similar". Hyped For History. 13 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Yermolenko, Galina I. (2016). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture. Routledge. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-317-06118-2.

- ^ a b Yermolenko, Galina (2005). "Roxolana: "The Greatest Empresse of the East"". The Muslim World. 95 (2): 231–248. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2005.00088.x. ISSN 0027-4909.

- ^ a b c d Bonnie G. Smith, ed. (2008). "Hürrem, Sultan". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195148909. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Abbott, Elizabeth (1 September 2011). Mistresses: A History of the Other Woman. Overlook. ISBN 978-1-59020-876-2.

- ^ Yermolenko, Galina I. (13 February 2010). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9781409403746.

- ^ a b "The Speech of Ibrahim at the Coronation of Maximilian II", Thomas Conley, Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Summer 2002), 266.

- ^ a b Kemal H. Karpat, Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History: Selected Articles and Essays, (Brill, 2002), p. 756.

- ^ Baltacı, Cahit. "Hürrem Sultan". İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Nahrawālī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad; Blackburn, Richard (2005). Journey to the Sublime Porte: the Arabic memoir of a Sharifian agent's diplomatic mission to the Ottoman Imperial Court in the era of Suleyman the Magnificent; the relevant text from Quṭb al-Dīn al-Nahrawālī's al-Fawāʼid al-sanīyah fī al-riḥlah al-Madanīyah wa al-Rūmīyah. Orient-Institut. pp. 200, 201 and n. 546. ISBN 978-3-899-13441-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yermolenko, Galina (April 2005). "Roxolana: 'The Greatest Empresse of the East'". The Muslim World. 95 (2): 231–248. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2005.00088.x.

- ^ Prymak, Thomas M. (2021). Ukraine, the Middle East, and the West. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 30. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1m0khf0. ISBN 978-0-2280-0771-5. S2CID 242150028.

- ^ Robert Lewis (1999). "Roxelana". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Faroqhi, Suraiya (2019). The Ottoman and Mughal Empires: Social History in the Early Modern World. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781788318723.

- ^ a b c d e f Levin, Carole (2011). Extraordinary women of the Medieval and Renaissance world: a biographical dictionary. Westport, Conn. [u.a.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30659-4.

- ^ a b "Ottoman Empire History Encyclopedia – Letter H – Ottoman Turkish history with pictures – Learn Turkish". practicalturkish.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Selçuk Aksin Somel: Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, Oxford, 2003, ISBN 0-8108-4332-3, p. 123

- ^ Peirce 1993, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Peirce 1993, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Peirce 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b Peirce 2017, pp. 9, 101

- ^ Mansel, Philip (1998). Constantinople : City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-18708-8. p, 86.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 91.

- ^ a b Peirce 1993, p. 109.

- ^ a b "Hürrem Sultan: A beloved wife or master manipulator? | Ottoman History". ottoman.ahya.net. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650 : The Structure of Power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-61386-3. p. 90.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 119.

- ^ "A Message for the Sultan – Sample Activity (Women in World History Curriculum)". womeninworldhistory.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ Pierce, Leslie. "The Imperial Harem : Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire".

- ^ Kumar, Lisa, ed. (2017). Encyclopedia of World Biography. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. pp. 305–306. ISBN 9781410324139

- ^ Akman, Mehmet (1997). Osmanlı devletinde kardeş katli. Eren. ISBN 978-975-7622-65-9.

- ^ Mansel, Phillip (1998). Constantinople : City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-312-18708-8.

- ^ Mansel, 87.

- ^ a b c Peirce, 55.

- ^ Mansel, 89.

- ^ a b "Historical Architectural Texture". Ayasofya Hürrem Sultan Hamamı. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Peri, Oded. Waqf and Ottoman Welfare Policy, The Poor Kitchen of Hasseki Sultan in Eighteenth-Century Jerusalem, pg 169

- ^ Blair, Sheila S.; Bloom, Jonathan (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam: 1250–1800. New Haven; London: Yale University Press. pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Khalidi, Walid. "Introduction." In Before Their Diaspora : A Photographic History of the Palestinians, 1876–1948, 27–35. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1991, 31.

- ^ Singer, Amy. Serving Up Charity: The Ottoman Public Kitchen, p. 486

- ^ Amy Singer: Constructing Ottoman Beneficence. An Imperial Soup Kitchen in Jerusalem. New York 2002, S. 17ff.

- ^ Gülru Necipoğlu: Queens: Wives and Mothers of Sultans. In: The age of Sinan. Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London 2005, S. 268–271.

- ^ Klaus Brisch (Hrsg.): Schätze aus dem Topkapi-Serail. Das Zeitalter Süleymans des Prächtigen. Berlin 1988, S. 38 u. 84.

- ^ Minna Rozen: A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul, The Formative Years, 1453 – 1566 (2002).

- ^ Öztuna, Yılmaz (1978). Şehzade Mustafa. İstanbul: Ötüken Yayınevi. ISBN 9754371415.

- ^ a b Talhami, Ghada. Historical Dictionaries of Women in the World: Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Scarecrow Press, 2012. p. 271

- ^ Talhami, Ghada. Historical Dictionaries of Women in the World: Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Scarecrow Press, 2012. p. 272

- ^ Chitchi, S. "Orientalist view on the Ottoman in the novel Roxalana (Hurrem Sultan) by Ukrainian author Pavlo Arhipovich Zahrebelniy". The Journal of International Social Research Vol. 7, Issue 33, p. 64

- ^ The Literature of the French Renaissance by Arthur Augustus Tilley, p. 87 Tilley, Arthur Augustus (December 2008). The Literature of the French Renaissance. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9780559890888. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge p.418 Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 1838. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Frederick A. de Armas "The Allure of the Oriental Other: Titian's Rossa Sultana and Lope de Vega's La santa Liga," Brave New Words. Studies in Spanish Golden Age Literature, eds. Edward H. Friedman and Catherine Larson. New Orleans: UP of the South, 1996: 191–208.

- ^ "Religious Information Service of Ukraine". Archived from the original on 22 December 2012.

- ^ "Reference to Roxelana's Russian origin removed from label near her tomb in Istanbul at Ukraine's request". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ a b Madar, Heather (2011). "Before the Odalisque: Renaissance Representations of Elite Ottoman Women". Early Modern Women. 6: 11. doi:10.1086/EMW23617325. JSTOR 23617325. S2CID 164805076.

- ^ Harold Edwin Wethey The Paintings of Titian: The Portraits, Phaidon, 1971, p. 275.

- ^ Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı; Karal, Enver Ziya (1975). Osmanlı tarihi, Volume 2. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. p. 401.

- ^ a b Peirce 2017.

Works cited

[edit]- Peirce, Leslie (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1950-8677-5.

- Peirce, Leslie (2017). Empress of the East: How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire. New York Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-4650-3251-8..

Further reading

[edit]- There are many historical novels in English about Roxelana: P.J. Parker's Roxelana and Suleyman (2012; Revised 2016); Barbara Chase Riboud's Valide (1986); Alum Bati's Harem Secrets (2008); Colin Falconer, Aileen Crawley (1981–83), and Louis Gardel (2003); Pawn in Frankincense, the fourth book of the Lymond Chronicles by Dorothy Dunnett; and pulp fiction author Robert E. Howard in The Shadow of the Vulture imagined Roxelana to be sister to its fiery-tempered female protagonist, Red Sonja.

- David Chataignier, "Roxelane on the French Tragic Stage (1561–1681)" in Fortune and Fatality: Performing the Tragic in Early Modern France, ed. Desmond Hosford and Charles Wrightington (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), 95–117.

- Parker, P. J. Roxelana and Suleyman (Raider Publishing International, 2011).

- Thomas M. Prymak, "Roxolana: Wife of Suleiman the Magnificent," Nashe zhyttia/Our Life, LII, 10 (New York, 1995), 15–20. An illustrated popular-style article in English with a bibliography.

- Galina Yermolenko, "Roxolana: The Greatest Empresse of the East," The Muslim World, 95, 2 (2005), 231–48. Makes good use of European, especially Italian, sources and is familiar with the literature in Ukrainian and Polish.

- Galina Yermolenko (ed.), Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture (Farmham, UK: Ashgate, 2010). ISBN 9780754667612 318 pp. Illustrated. Contains important articles by Oleksander Halenko and others, as well as several translations of works about Roxelana from various European literatures, and an extensive bibliography.

- For Ukrainian language novels, see Osyp Nazaruk (1930) (English translation is available), Mykola Lazorsky (1965), Serhii Plachynda (1968), and Pavlo Zahrebelnyi (1980).

- There have been novels written in other languages: in French, a fictionalized biography by Willy Sperco (1972); in German, a novel by Johannes Tralow (1944, reprinted many times); a very detailed novel in Serbo-Croatian by Radovan Samardzic (1987); one in Turkish by Ulku Cahit (2001).

External links

[edit]- 1504 births

- 1558 deaths

- 16th-century consorts of Ottoman sultans

- Ruthenian people

- Converts to Islam from Eastern Orthodoxy

- People from Ruthenian Voivodeship

- People from Rohatyn

- Suleiman the Magnificent

- Former Christians from the Ottoman Empire

- Mothers of Ottoman sultans

- Women slaves

- 16th-century slaves from the Ottoman Empire

- Sultanate of Women

- Concubines of Ottoman sultans

- Royal favourites

- Haseki Sultan