John Romita Jr.

| John Romita Jr. | |

|---|---|

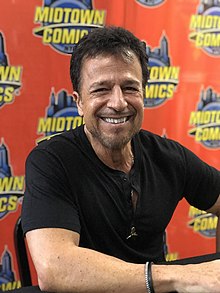

Romita at a signing at Midtown Comics in Manhattan | |

| Born | August 17, 1956 New York City, U.S. |

| Area(s) | Penciller |

| Pseudonym(s) | JRJR |

Notable works | The Amazing Spider-Man Daredevil Iron Man Kick-Ass Superman Uncanny X-Men |

| Awards | Inkpot Award (1994) Eisner Award (2002) |

John Salvatore Romita[1] (/rəˈmiːtə/; born August 17, 1956)[2] is an American comics artist best known for his extensive work for Marvel Comics from the 1970s to the 2010s. He is the son of artist John Romita Sr.

Early life

[edit]John Romita Jr. was born August 17, 1956,[2] the son of Virginia (Bruno) and comic book artist John Romita Sr., one of the signature Spider-Man artists since the 1960s.[3][4] He studied advertising art and design at Farmingdale State College in East Farmingdale, New York, graduating in 1976.[5]

Career

[edit]Romita Jr.'s first contribution to Marvel Comics was at the age of 13 with the creation of the original Prowler, a sketch of which Romita had produced. Editor Stan Lee liked the name but not the costume; Romita combined the name with a design that he had previously intended for a character called the Stalker that was intended for the never-published The Spectacular Spider-Man #3.[6] Inspired by Romita's drawing, Lee, John Buscema and Jim Mooney created the Hobie Brown version of the character that would debut in The Amazing Spider-Man #78 (Nov. 1969).[7]

Romita Jr. began his career at Marvel UK, doing sketches for covers of reprints. His American debut was a pin-up on Kid Colt Outlaw #218 and two months later with a six-page story entitled "Chaos at the Coffee Bean!" in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #11 (1977).[1][8]

Romita's early popularity began with his run on Iron Man with writer David Michelinie and artist Bob Layton which began in 1978. The creative team introduced several supporting characters, including Tony Stark's bodyguard girlfriend Bethany Cabe[9] and rival industrialist Justin Hammer.[10] In the early 1980s, he had his first regular run on the series The Amazing Spider-Man and also was the artist for the launch of the Dazzler series. He and writer Dennis O'Neil introduced Madame Web in The Amazing Spider-Man #210 (Nov. 1980)[11] and Hydro-Man in issue #212 (Jan. 1981).[12] In 1982, Romita Jr. drew Marvel Super Hero Contest of Champions[13] the first limited series published by Marvel Comics. Working with writer Roger Stern on The Amazing Spider-Man, he co-created the character Hobgoblin.[14] From 1983 to 1986 he had a run on the Uncanny X-Men with Dan Green and author Chris Claremont and co-created Forge.[15] Romita has downplayed the significance of his run, saying that few of the characters introduced during this time were co-created by him and that his style has had no discernible influence on succeeding X-Men artists. His relationship with Claremont was rather cool at the time, as Claremont did not like his work as much as the artists he had previously worked with.[16] He would return for a second run on Uncanny X-Men in 1993,[8] which he said he liked better "because of getting to work with [writer] Scott Lobdell."[16]

After he ended his first run on The Uncanny X-Men, Romita was assigned to Star Brand, one of the titles on Marvel's New Universe imprint, which featured a character the Romita was told would be Marvel's version of Superman. The title did not do well in sales, and Romita could not return to the X-Men. This experience, and personality conflicts that he had with those in editorial left Romita so disillusioned that he considered quitting the industry entirely. However, editor Ralph Macchio approached him one day as Romita was leaving the Marvel offices and asked him to consider working on Daredevil. Romita had never considered working on that character, despite the fact that his father had done so, but Macchio said he would be paired with writer Ann Nocenti, and that he would not only be allowed to do full pencils for the first time[17] (having previously been restricted to doing only breakdowns[18]), but would also collaborate on plots, and be allowed to choose his own inker. A skeptical Romita jokingly said he wanted Al Williamson, and was surprised when Williamson was assigned was confirmed a day later.[17] For Romita himself, his stint on Daredevil was most significant for being both the first time he was allowed to do full pencils, and the first time he had a working relationship with the writer on a series. He later remarked that "I finally felt like I was part of the creation process for the first time while I was on DD."[18] In a 2017 interview with SyFy Wire, Romita stated this run reinvigorated his enthusiasm for comics work, marking a turning point in his career. His run on the title from 1988 to 1990 included the creation of long-running Daredevil nemesis Typhoid Mary.[19] After Daredevil #282, Romita left the series to pursue other projects, though his experience on Daredevil would influence his later return to the character with Frank Miller.[17]

Stan Lee interviewed Romita and his father in Episode 8 of the 1991–1992 documentary series The Comic Book Greats.

He worked on a host of Marvel titles during the 1990s, including a return to Iron Man for the second "Armor Wars" story arc, written by John Byrne; The Punisher War Zone;[20] the Cable miniseries;[21] and the Punisher/Batman crossover. Klaus Janson was a frequent inker.[8]

Romita contacted Frank Miller and told him that he wanted to collaborate on a graphic novel, suggesting they work on Wolverine. Miller dismissed this, saying that too many other creators were producing books featuring that character, and instead sent Romita a rejected 64-page film treatment for what was essentially a "Daredevil Year One"-type story. After Romita completed adapating the story into comics form, Miller told him that he had written an addendum to be set in between Pages 17 and 18, which ended up adding 84 more pages to the book, changing its format. The result was the 144-page, 5-issue miniseries Daredevil: The Man Without Fear,[17][18] which was published in 1993,[22] The book was a retelling of the character's origin, which reunited Romita with Williamson on inks.[18] In a 2017 interview, Romita said that in terms of storytelling, he thought that Man Without Fear was the best work he had ever done,[17][18] due to the strong storytelling and the quality of the story.[3][17] Elements from the storyline were adapted into the 2015 Netflix series Daredevil.[17]

In July 1998 Dan Jurgens and Romita Jr. relaunched the Thor series.[23]

A January 1999 reboot of Peter Parker: Spider-Man was handled by Howard Mackie and Romita Jr.[24]

In 2001, Romita returned to Spider-Man for a collaboration with writer J. Michael Straczynski beginning with The Amazing Spider-Man vol. 2 #30 (June 2001).[25] The creative team produced a story for issue #36 (Dec. 2001) that served as memorial to the victims of the September 11 attacks.[26] He drew Marvel's Wolverine with author Mark Millar. In 2004, Romita's creator-owned project The Gray Area was published by Image Comics. He subsequently worked on the Marvel series Black Panther, The Sentry and "Ultimate Vision", a backup feature in the Ultimate Marvel line, written by Mark Millar.[8]

In 2006, Romita collaborated with writer Neil Gaiman on a seven-issue miniseries reinterpretation of Jack Kirby's characters the Eternals.[27][28] Romita worked with Greg Pak on the five-issue central miniseries of Marvel's 2007 crossover storyline, "World War Hulk".[29][30]

In 2008, Romita again returned to The Amazing Spider-Man.[31] He also collaborated once more with Millar, for a creator-owned series, Kick-Ass, published by Marvel's Icon imprint. This was later adapted into the 2010 film Kick-Ass. Romita, one of the producers, directed an animated flashback sequence in the film.[32]

Also in 2010 he relaunched the Avengers title with popular writer Brian Michael Bendis as part of Marvel's Heroic Age initiative.[33]

On April 9, 2011, Romita was one of 62 comics creators who appeared at the IGN stage at the Kapow! convention in London to set two Guinness World Records, the "Fastest Production of a Comic Book" and "Most Contributors to a Comic Book". With Guinness officials on hand to monitor their progress, writer Millar began work at 9 a.m. scripting a 20-page black-and-white comic book of his character Superior, with Romita and the other artists appearing on stage throughout the day to work on the pencils, inks, and lettering, each drawing a panel.[34][35] The book was completed in 11 hours, 19 minutes, and 38 seconds, and was published through Icon on November 23, 2011, with all royalties being donated to Yorkhill Children's Foundation.[34]

On May 4, 2012, Romita set out to break his own record for continuous cartooning, to support the charity Candlelighters Childhood Cancer Foundation of Nevada. He attempted to continuously sketch characters and sign comics for 50 hours straight.[36]

In 2014, Romita Jr. became the penciller of the DC Comics flagship title Superman, starting with issue #32, in collaboration with writer Geoff Johns.[37][38] Romita Jr.'s Superman pencils have been inked by Klaus Janson.[39] In 2016, Romita Jr. and writer Scott Snyder collaborated on the All-Star Batman series as part of the DC Rebirth relaunch.[40][41] Romita Jr. and writer Dan Abnett created The Silencer series as part of DC's "Dark Metal" line.[42] In addition, Romita worked with Frank Miller on the Superman: Year One mini-series.[43][44]

In 2020, Romita drew Kelly Sue DeConnick's story "Fore" for Detective Comics' 1027th issue.[45]

In 2022 he once again returned to the Amazing Spider-Man title, this time with writer Zeb Wells[46]

Influences and techniques

[edit]Romita's art influences include his father John Romita Sr.,[3] as well as comics artists Jack Kirby[3] and John Buscema,[3] the Wyeth family of painters,[3] and illustrator Charles Dana Gibson.[3]

Having illustrated both gritty street-level stories of characters such as Spider-Man and Daredevil and cosmic stories such as those starring Thor, Romita says he prefers the former, because "that is where I grew up. I use the same approach to each of the different story types – the story tells me what to do."[3] He prefers to work in the Marvel Method.

Awards

[edit]John Romita Jr. received an Inkpot Award in 1994.[47]

With writer J. Michael Straczynski and inker Scott Hanna, Romita Jr. won a 2002 Eisner Award for Best Serialized Story: The Amazing Spider-Man #30-35: "Coming Home".[48]

Bibliography

[edit]DC Comics

[edit]- Action Comics #1017–1028 (2019–2020)

- All-Star Batman #1–5 (2016)

- Batman vol. 3 #80–81 (2019)

- Batman Black and White vol. 5 #6 (among other artists, 2021)

- Dark Days: The Casting #1 (one-shot, with Jim Lee and Andy Kubert, 2017)

- Dark Days: The Forge #1 (one-shot, with Lee and Kubert, 2017)

- Dark Knight III: The Master Race #3 (backup story, 2016)

- Dark Knight Returns: The Last Crusade (one-shot, 2016)

- Detective Comics #1027 (among other artists, 2020)

- The Silencer #1–3 (2018)

- Suicide Squad vol. 4 #11–15 (2017)

- Superman vol. 3 #32–44 (2014–2015)

- Superman: Year One #1–3 (2019)

Image Comics

[edit]- The Gray Area #1–3 (2004)

- Kick-Ass #1–6 (2018)

Marvel Comics

[edit]- The Amazing Spider-Man #208, 210–218, 223–227, 229–236, 238–250, 290–291, 432, 500–508, 568–573, 584–585, 587–588, 600, 692, Annual #11, 16 (1980–1984, 1987, 1995, 1998, 2003–2004, 2008–2009, 2012)

- The Amazing Spider-Man vol. 2, #22–27, 30–58 (2000–2003)

- The Amazing Spider-Man vol. 6 #1-5, 7-8, 11-13, 21-26, 31, 39-44, 49, 56-60 (2022-)

- The Avengers vol. 3 #35 (2000)

- The Avengers vol. 4 #1–12, 14, 16–17 (2010–2011)

- Black Panther vol. 3, #1–6 (2005)

- Cable: Blood and Metal #1-2 (miniseries, 1992)

- Captain America vol. 7, #1–10 (2013)

- Daredevil #250–257, 259–263, 265–276, 278–282, Annual #5 (1988–1990)

- Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #1-5 (1993–1994)

- Dark Reign: The List – Punisher #1 (2009)

- Dazzler #1–3 (1981)

- Eternals vol. 3 #1–7 (2006–2007)

- Fall of the Hulks: Gamma #1 (2010)

- Fallen Son: The Death of Captain America #4 (2007)

- Fantastic Four vol. 6 #35 (2021)

- Free Comic Book Day 2010: Iron Man/Thor #1 (2010)

- Ghost Rider/Wolverine/Punisher: Hearts of Darkness #1 (1991)

- Heroes for Hope Starring the X-Men #1 (1985)

- The Incredible Hulk vol. 3 #24–25, 27–28, 34–39 (2001–2002)

- Iron Man #115–117, 119–121, 123–128, 141–150, 152–156, 256, 258–266 (1978–1982, 1990–1991)

- The Last Fantastic Four Story (2007)

- Marvel Super Hero Contest of Champions #1-3 (1982)

- Marvel Super Special #5 (Kiss) (1978)

- The Mighty Avengers #15 (2008)

- Peter Parker: Spider-Man #57, 64–76, 78–84, 86–92, 94–95, 97–98 (1995–1998)

- Peter Parker: Spider-Man vol. 2, #1–3, 6–12, 14–17, 19 (1999–2000)

- The Punisher War Zone #1–8 (1992)

- Scarlet Spider #2 (1995)

- Sentry vol. 2 #1–8 (miniseries, 2005–2006)

- The Spectacular Spider-Man #50, 121 (1981, 1986)

- Spider-Man: The Lost Years #0, 1–3 (miniseries, 1995)

- Star Brand #1–2, 4–7 (1986–1987)

- Thor vol. 2, #1–8, 10–13, 16–18, 21–25 (1998–2000)

- Ultimate Vision #0 (2007)

- Uncanny X-Men #175–185, 187–197, 199–200, 202–203, 206–211, 287, 300–302, 304, 306–311, Annual #4 (1980–1986, 1992–1994)

- Wolverine vol. 3, #20–31 (2004–2005)

- World War Hulk #1–5 (2007–2008)

- X-Men: Legacy #208 (2008)

- X-Men Unlimited #7 (1994)

Icon Comics

[edit]- Hit-Girl #1–5 (2012–2013)

- Kick-Ass #1–8 (with writer Mark Millar 2008–2010)

- Kick-Ass 2 #1–7 (2010–2012)

- Kick-Ass 3 #1–8 (2013–2014)

Marvel Comics / DC Comics

[edit]- Punisher/Batman: Deadly Knights (intercompany crossover, 1994)

- Thorion of the New Asgods #1 (1997)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "John Romita Jr". Lambiek Comiclopedia. June 3, 2012. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Miller, John Jackson (June 10, 2005). "Comics Industry Birthdays". Comics Buyer's Guide. Iola, Wisconsin. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Andreasen, Henrik; Keller, Katherine (November 19, 2007). "Like Father Like Son: John Romita Jr". SequentialTart.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ Ross, Alex, Introduction, in Spurgeon, Tom; Cunningham, Brian (2011). The Romita Legacy. Mount Laurel, New Jersey: Dynamic Forces. p. 5. ISBN 978-1933305271. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ "Farmingdale State College To Hold Alumni Awards Dinner Next March 31". East Farmingdale, New York: Farmingdale State College. December 10, 2015. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Wells, John (2014). American Comic Book Chronicles: 1965-1969. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 269. ISBN 978-1605490557.

- ^ DeFalco, Tom (2008). "1960s". In Gilbert, Laura (ed.). Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. Dorling Kindersley. p. 139. ISBN 978-0756641238.

Future Marvel artist John Romita, Jr. – who was thirteen years old at the time- came up with a character called the Prowler and sent a drawing to Stan Lee.

- ^ a b c d John Romita Jr. at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Sanderson, Peter "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 187: "In December [1978], co-plotters David Michelinie and Bob Layton, and penciler John Romita Jr....came up with Bethany Cabe, a highly capable professional bodyguard and a different sort of leading lady."

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 189: "Tony Stark's billionaire nemesis Justin Hammer made his first appearance in The Invincible Iron Man #120 by writer David Michelinie and artist John Romita Jr. and Bob Layton. "

- ^ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1980s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 116. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Writer Denny O'Neil's newest contribution to the Spider-Man mythos would come in the form of psychic Madame Web, a character introduced with the help of artist John Romita Jr.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 118: "In this issue, award-winning writer Denny O'Neil, with collaborator John Romita Jr., introduced Hydro-Man."

- ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 208: "Plotted by Mark Gruenwald, Steven Grant, and Bill Mantlo, and penciled by John Romita Jr., Contest of Champions eventually saw print in June 1982"

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 133: "Writer Roger Stern and artists John Romita Jr. and John Romita Sr. introduced a new – and frighteningly sane – version of the [Green Goblin] concept with the debut of the Hobgoblin."

- ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 218: "A brilliant weapons inventor Forge was the man the government hired when Tony Stark stopped building munitions."

- ^ a b Gagnon, Mike (August 2008). "The X-Traordinary John Romita, Jr". Back Issue! (29). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 73–77.

- ^ a b c d e f g "How Daredevil Saved John Romita Jr". SyFy Wire. August 23, 2017. Archived from the original on October 16, 2023. Retrieved September 19, 2023 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e Cordier, Philippe (April 2007). "Seeing Red: Dissecting Daredevil's Defining Years". Back Issue! (21). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 33–60.

- ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 237: "Mary was first introduced in Daredevil #254 by [writer] Ann Nocenti and artist John Romita Jr."

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 258: "The third ongoing series to star vigilante Frank Castle was The Punisher: War Zone, written by Chuck Dixon and with art by John Romita Jr. and Klaus Janson."

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 260

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 264: "Comic legends Frank Miller and John Romita Jr. united to tell a new version of Daredevil's origin in this carefully crafted five-issue miniseries."

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 289: "Thor thundered into his new ongoing series by writer Dan Jurgens and artist John Romita Jr."

- ^ Cowsill, Alan "1990s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 246: The second new Spidey title of the month featured a tale written by Howard Mackie and drawn by John Romita Jr."

- ^ Cowsill "2000s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 262: "J. Michael Straczynski and artist John Romita Jr. took the helm in this issue to create some of the best Spider-Man stories of the decade."

- ^ Cowsill "2000s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 265: "The most powerful Spider-Man comic of the year was Straczynski and Romita Jr.'s response to the horrific events of 9–11...Spider-Man's 9-11 story was a highly charged, beautifully produced tribute to the heroes and victims of the attack."

- ^ Richards, Dave (June 9, 2006). "Following in the Footsteps: Romita Talks Eternals". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ MacQuarrie, Jim (August 3, 2007). "CCI XTRA: Spotlight on Neil Gaiman". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ Manning "2000s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 336: "Writer Greg Pak teamed up with legendary artists John Romita Jr. and Klaus Janson for the largest crossover event of 2007, World War Hulk."

- ^ Ong Pang Kean, Benjamin (September 14, 2006). "John Romita Jr.: Returning to and with the Hulk". Newsarama. Archived from the original on March 20, 2007.

- ^ Cowsill "2000s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 314

- ^ Weintraub, Steve (2010). "John Romita Jr. Interview: Kick-Ass". Collider.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Dave Richards (February 19, 2010). "Bendis Assembles his Avengers". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ a b Butler, Tom (April 14, 2011). "Kapow! '11: Comic History Rewritten On The IGN Stage". IGN. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014.

- ^ "Guinness World Records at Kapow! Comic Con". Guinness World Records. April 9, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011.

- ^ Wright, Eddie (April 26, 2012). "John Romita Jr. to Break Guinness World Record for Heroes for Jordan". MTV. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (February 4, 2014). "Scoop: The New Look For John Romita Jr's Superman – And Confirmation That Geoff Johns Will Be Writing It". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on February 6, 2014.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (February 4, 2014). "John Romita Jr. Signs with DC for Superman with Geoff Johns". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 6, 2014.

- ^ Khouri, Andy (February 4, 2014). "Geoff Johns Returns To Superman In Collaboration With John Romita Jr". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on February 6, 2014.

- ^ Gaudette, Emily (August 11, 2016). "In All-Star, Batman Has 'A Target on Him, Nowhere to Go'". Inverse.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016.

DC has just released All-Star Batman, a dark road-trip story in the American midwest. The superhero-horror comic, created by beloved DC heavyweights Scott Snyder and John Romita Jr., is the freshest and scariest Batman story since 1988's The Cult.

- ^ Marston, George (March 29, 2016). "Scott Snyder: All-Star Batman Is 'My Long Halloween'". Newsarama. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016.

- ^ Gerding, Stephen (April 21, 2017). "Exclusive: John Romita Jr. Discusses Dark Matter Work, Influences". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017.

The artist described his and writer Dan Abnett's Silencer title as something akin to 'a female John Wick.'

- ^ Arrant, Chris (July 22, 2017). "Superman: Year One By Frank Miller & John Romita Jr". Newsarama. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (July 20, 2018). "Sneak Peek Inside DC Black Label's Batman: Damned and Superman: Year One". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018.

- ^ Dominguez, Noah (September 13, 2020). "Detective Comics #1027". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Rich Johnston (January 13, 2022). "Marvel Comics Relaunches Amazing Spider-Man #1 In April 2022". Bleeding cool. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ "Inkpot Award Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012.

- ^ "2002 Eisner Awards". Comic-Con International. December 2, 2012. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Chris (2015). "Superman redrawn". Book Club. SciFiNow. 104: 100–103.

External links

[edit]- John Romita Jr. at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- John Romita Jr. on Marvel.com

- John Romita Jr. Archived August 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at Mike's Amazing World of Comics

- John Romita Jr. at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- John Romita Jr. at IMDb