Riffians

الريفيون | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| Around 1.2 million (3.2% of Moroccan population; 2024 census)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Tarifit, Moroccan Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam[2][3][4] |

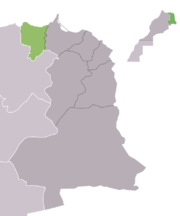

Riffians or Rifians (Tarifit: Irifiyen, singular: Arifi;[5] Arabic: الريفيون) are a Berber ethnic group originally from the Rif region of northeastern Morocco (includes the autonomous city of Spain, Melilla).[3] Communities of Riffian immigrants are also found in southern Spain, Netherlands and Belgium as well as elsewhere in Western Europe.[6] They are overwhelmingly Sunni Muslims, but retain their pre-Islamic traditions such as high status for Riffian women.[3]

According to Irina Casado i Aijon, Riffians have traditionally organized themselves under "patrilineality and patrilocality principles".[6] The oldest man in the household commands authority and responsibility for decisions, while women jointly care for the young and sick without any discrimination. Like other Berbers, temporary migration is an accepted tradition.[7] The Riffians have been a significant source of Moroccan emigrants into some European countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.[8][9][10]

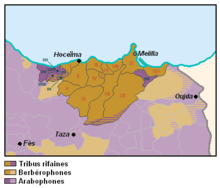

Riffians speak Tarifit, which belongs to the Zenati group of Berber languages.[3] The languages spoken depend on the region, with many Riffians who speak a Berber language also speaking Moroccan Arabic or Spanish. Nineteen groups or social units of Riffians are known: five in the west along the Mediterranean coast which speak Riffian and Moroccan Arabic, seven in the centre of which one speaks mainly Moroccan Arabic and rest Riffian, five in the east and two in the southeastern desert area also speak the Riffian language.[2]

They have inhabited an impoverished and an eroded, deforested, poorly irrigated region. Poverty rates and infant mortality rates among Riffians have been high, according to a study published in 1980 by Terri Joseph.[11] The Riffians have lived a largely settled, agricultural lifestyle, using hand tools, oxen and cattle to plow the steeply terraced land in their valleys. Horticultural produce along with sheep and goat meat, cheese, and milk provide the traditional sustenance.[11] Some practice sardine-seining along the Mediterranean coast.[2]

Riffians have experienced numerous wars over their history. Some of their cultural traditions reflects and remembers this history, such as the singing and dancing of Ayara Liyara, Ayara Labuya, which literally means "Oh Lady oh Lady, oh Lady Buya" and is accompanied by izran (couplets) and addjun (tambourine tapping).[12] This tradition, states Hsain Ilahiane, is linked to the 11th-century destruction and deaths of the Riffian fathers during the raid by the Almoravid leader Yusuf ibn Tashfin.[12] In more modern times, the Rif War caused numerous deaths of Riffian people and of Spanish as well as French soldiers. The Rif War witnessed the use of chemical weapons in the 1920s by the Spanish army.[13][14]

In 1958, some Riffians revolted against the government.[3] In the decades that followed, the Rif region has witnessed popular demonstrations and demands for better education, healthcare and job opportunities. A resurgent Riffian popular movement in 2010, their protests in 2013 and protests in 2017 for hogra – a humiliating treatment by an abusive state – has drawn public attention, as well as claims of brutal suppression by Moroccan authorities.[3][15][16]

Tribes and tribal groups

[edit]The Riffians are divided into these tribes and tribal groups:[17]

- Ait Ammart

- Ait Boufrah

- Ait Bouyahyi

- Ait Gmil

- Ait Itteft

- Ait Ourich

- Ait Said

- Ait Tafersit

- Ait Temsamane

- Ait Touzine

- Ait Waryaghar

- Ibaqouyen

- Ibdarsen

- Igzenayen

- Ikebdanen

- Iqer'iyen

- Mestassa

See also

[edit]- Ghomara language

- Senhaja de Srair language

- Senhaja de Srair in the Central Rif

- Ghomara in the Western Rif

- Jbala in the Western Rif

- Beni Iznasen in the Eastern Rif

- Beni Snous Tlemcen, Western Algeria

References

[edit]- ^ Gauthier, Christophe. "كلمة افتتاحية للسيد المندوب السامي للتخطيط بمناسبة الندوة الصحفية الخاصة بتقديم معطيات الإحصاء العام للسكان والسكنى 2024". Site institutionnel du Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ a b c The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, Rif people, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ a b c d e f James B. Minahan (2016). Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-61069-954-9.

- ^ Lucien Oulahbib, Le monde arabe existe-t-il ?, page 12, 2005, Editions de Paris, Paris.

- ^ Hart, David M. (1976). The Aith Waryaghar of the Moroccan Rif: An Ethnography and History. Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8165-0452-7.

- ^ a b Irina Casado i Aijon (2013). Laura Oso; Natalia Ribas-Mateos (eds.). The International Handbook on Gender, Migration and Transnationalism. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 450 with notes 2–8. ISBN 978-1-78195-147-7.

- ^ Irina Casado i Aijon (2013). Laura Oso; Natalia Ribas-Mateos (eds.). The International Handbook on Gender, Migration and Transnationalism. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 439–449. ISBN 978-1-78195-147-7.

- ^ Malcolm Klein; Hans-Jürgen Kerner; Cheryl Maxson; et al. (2012). The Eurogang Paradox: Street Gangs and Youth Groups in the U.S. and Europe. Springer Science. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-94-010-0882-2.

- ^ Maurice Crul; Flip Lindo; Ching Lin Pang (1999). Culture, Structure and Beyond. Het Spinhuis. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-90-5589-173-3.

- ^ James Minahan (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 1590–1592. ISBN 978-0-313-32111-5.

- ^ a b Joseph, Terri Brint (1980). "Poetry as a Strategy of Power: The Case of Rifian Berber Women". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 5 (3). University of Chicago Press: 418–434. doi:10.1086/493728. S2CID 14712463.

- ^ a b Hsain Ilahiane (2017). Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4422-8182-0.

- ^ James A. Romano Jr.; Harry Salem; Brian J. Lukey (2007). Chemical Warfare Agents: Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutics, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4200-4662-5.

- ^ Martin Thomas (2008). Empires of Intelligence: Security Services and Colonial Disorder After 1914. University of California Press. pp. 147–149. ISBN 978-0-520-25117-5.

- ^ David S. Woolman (1968). Rebels in the Rif: Abd el Krim and the Rif Rebellion. Stanford University Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-08047-066-43.

- ^ Rough in the Rif: Morocco’s unrest is worsening, The Economist (July 8, 2017), Quote: "The trouble began in October after a fishmonger called Mouhcine Fikri was crushed by a garbage compactor at a port in Al Hoceima, which is located in the Rif, a northern mountain region with a rebellious streak. Fikri was trying to retrieve fish that had been confiscated by the authorities. To locals, his death was a striking example of hogra—humiliating treatment by an abusive state. (...) The government has since exacerbated the situation with yet more hogra. In May it called the protesters separatists, though most are not, and suggested that they were foreign agents. (...) The unrest not only increased, but spread to other parts of the country, including Rabat, the capital, where on June 11th thousands of people rallied in support of the Riffians. All told, it is the largest display of public anger in Morocco since the Arab spring in 2011."

- ^ Coon, Charleton S. (1931). Tribes of the Rif. Harvard African studies.v. 9. University of Harvard. p. 4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Riffian people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Riffian people at Wikimedia Commons