Richard Swann Lull

Richard Swann Lull | |

|---|---|

Portrait by William Sergeant Kendall | |

| Born | November 6, 1867 Annapolis, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | April 22, 1957 (aged 89) |

| Alma mater | Rutgers College Columbia University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology |

| Institutions | Massachusetts Agricultural College Yale University |

| Doctoral advisor | Henry Fairfield Osborn |

| Notable students | George Gaylord Simpson[1] |

Richard Swann Lull (November 6, 1867 – April 22, 1957) was an American paleontologist and Sterling Professor at Yale University who is largely remembered for championing a non-Darwinian view of evolution, whereby mutation(s) could unlock presumed "genetic drives" that, over time, would lead populations to increasingly extreme phenotypes (and perhaps, ultimately, to extinction).

Life

[edit]

Lull was born in Annapolis, Maryland, the son of naval officer Edward Phelps Lull and Elizabeth Burton, daughter of General Henry Burton. He married Clara Coles Boggs, and he has a daughter, Dorothy. He majored in zoology at Rutgers College, where he received both his undergraduate and master's degrees (M.S. 1896). He worked for the Division of Entomology of the United States Department of Agriculture but in 1894 became an assistant professor of zoology at the State Agricultural College in Amherst, Massachusetts (now the University of Massachusetts Amherst). Lull's interest in fossil footprints began at Amherst College, renowned for its collection of fossil footprints, and eventually led him to switch from entomology to paleontology.

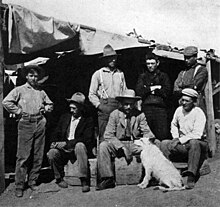

In 1899, Lull worked as a member of the American Museum of Natural History's expedition to Bone Cabin Quarry, Wyoming, helping to collect that museum's brontosaur skeleton. In 1902 he again joined an American Museum team in Montana, then studied under Columbia University professor Henry Fairfield Osborn. In 1903 he received his Ph.D. from Columbia University, and in 1906, after a brief time at Amherst, he was named assistant professor of Vertebrate Paleontology in Yale College and Associate Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Peabody Museum of Natural History. He stayed at Yale for the next 50 years. In 1933, Lull was awarded the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences.[2]

One famous example he used to support his non-Darwinian evolution theory concerned the enormous antlers of the Irish elk: he argued that these could not possibly be the result of natural selection, and instead reflected one of his "unlocked genetic drives" toward ever-increasing antler size. The poor elk, coping in each generation with ever-bigger antlers were eventually driven extinct.[3] His evolutionary theory was a form of orthogenesis.[4]

His book Organic Evolution (1917) received positive reviews and was described as an "excellent summary of the theories, facts, and factors of evolution."[5][6]

Publications

[edit]- Fossils: What They Tell Us of Plants and Animals of the Past (1931)

- A Revision of the Ceratopsia or Horned Dinosaurs (1933)

- The Ways of Life (1925)

- Organic Evolution (1917)

- Fossil Footprints of the Jura-Trias of North America (1904)

References

[edit]- ^ "Richard Swann Lull". Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Yale University. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1977). "The Misnamed, Mistreated, and Misunderstood Irish Elk". Ever Since Darwin (PDF). New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 79–90.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (1992). The Eclipse of Darwinism: Anti-Darwinian Evolution Theories in the Decades around 1900. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0801843914.

- ^ Anonymous. (1917). Organic Evolution by Richard Swann Lull. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 36 (4) 281-282.

- ^ S. W. W. (1918). Organic Evolution, a Text-Book by Richard Swann Lull. The Journal of Geology 26 (3): 285-286.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Richard Swann Lull at the Internet Archive

- Works by Richard Swann Lull at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)