The Red Book (Jung)

Liber Novus, original of 'The Red Book' | |

| Author | Carl Gustav Jung |

|---|---|

| Original title | Liber Novus ("New Book") |

| Translator | Mark Kyburz John Peck Sonu Shamdasani |

| Illustrator | Carl Jung |

| Language | German (First published alongside English translation) |

| Genre | diary |

| Publisher | Philemon Foundation and W. W. Norton & Co. |

Publication date | 2009 |

| Pages | 404 |

| ISBN | 978-0-393-06567-1 |

| OCLC | 317919484 |

| 150.19/54 22 | |

| LC Class | BF109.J8 A3 2009 |

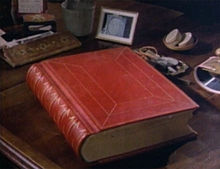

The Red Book: Liber Novus is a folio manuscript so named due to its original red leather binding. The work was crafted by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung between 1914[1]: 40 (ft.124) and about 1930. It follows, records and comments in fair copy on the author's psychological observations and experiments on himself between 1913 and 1916, and draws on working drafts contained in a series of notebooks or journals, now known as the Black Books. Jung produced these beginning in 1913 and continued until 1917.[2][3] Despite being considered as the origin of Jung's main oeuvre,[4] it was probably never intended for conventional publication and the material was not published nor made otherwise accessible for study until 2009.

In October 2009, with the cooperation of Jung's estate, The Red Book was published by W. W. Norton in a facsimile edition, complete with an English translation, three appendices, and over 1,500 editorial notes.[5] Editions and translations in several other languages soon followed.

In December 2012, Norton additionally released a "Reader's Edition" of the work; this smaller format edition includes the complete translated text of The Red Book along with the introduction and notes prepared by Sonu Shamdasani, but it omits the facsimile reproduction of Jung's original calligraphic manuscript.[1]

While the work has in past years been commonly referred to as "The Red Book", Jung did emboss a formal title on the spine of his leather-bound folio: his chosen title for the work was Liber Novus—Latin for "New Book". His manuscript is now increasingly cited as Liber Novus, and under this title implicitly includes draft material intended for but never finally transcribed into the red leather folio proper.[3]

Context and composition

[edit]Jung was closely associated with his senior colleague from Vienna Sigmund Freud for a period of approximately six years, beginning in 1907. Over those years, their relationship produced many fruitful exchanges, but also cemented and highlighted each man's attachment to his convictions as to the nature and dynamics of the human psyche. Inevitably, their collaboration became increasingly fractious. When the final break in the relationship came in 1913, it was to have far reaching consequences. Jung retreated from many of his professional activities to reconsider intensely his personal and professional path.[6] The creative activity that produced Liber Novus came in this period, from 1913 to about 1917. Its genesis coincided with the gathering storm clouds of World War I, its outbreak and engulfing conflict.

Biographers and critics have disagreed whether these years in Jung's life should be seen as "a creative illness", a period of introspection, a psychotic breakdown or simply as a period of madness.[7] Anthony Storr, reflecting on Jung's own judgment that he was "menaced by a psychosis" during this time, concluded that the period represented a psychotic episode.[8] According to Sonu Shamdasani, Storr's opinion is unsustainable in light of currently available documentation.[9] Jung himself stated that: "To the superficial observer, it will appear like madness".[10] It appears that Jung had anticipated the arguments of the likes of Storr and Jung biographer Paul Stern and, in riposte, would likely have regarded the analyses of Storr and Stern as superficial.[8]

During the years Jung engaged with his "nocturnal work" on Liber Novus, he continued to function in his daytime activities without apparent impairment.[11] He maintained a busy professional practice, seeing on average five patients a day. He carried out research, lectured, wrote, and remained active in professional associations.[12] Throughout this period he also served as an officer in the Swiss army and was on active duty for several extended periods between 1914 and 1918 during World War I.[13]

Jung referred to his imaginative or visionary venture during these years as "my most difficult experiment".[14] This experiment involved a voluntary confrontation with the unconscious through wilful engagement of what Jung later termed "mythopoetic imagination".[15][16] In his introduction to Liber Novus, Shamdasani explains:

From December 1913 onward, he carried on in the same procedure: deliberately evoking a fantasy in a waking state, and then entering into it as into a drama. These fantasies may be understood as a type of dramatized thinking in pictorial form.... In retrospect, he recalled that his scientific question was to see what took place when he switched off consciousness. The example of dreams indicated the existence of background activity, and he wanted to give this a possibility of emerging, just as one does when taking mescaline.[17]

Jung initially recorded his "visions", or "fantasies", or "imaginations"—all terms used by Jung to describe his activity[18]—in a series of six journals now known collectively as the "Black Books".[19] This journal record begins on 12 November 1913, and continues with intensity through the summer of 1914; subsequent entries were added up through at least the 1930s.[2] Biographer and psychoanalyst Barbara Hannah, who was close to Jung throughout the last three decades of his life, compared Jung's imaginative experiences recounted in his journals to the encounter of Menelaus with Proteus in the Odyssey. Jung, she said, "made it a rule never to let a figure or figures that he encountered leave until they had told him why they had appeared to him."[20]

After the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Jung perceived that his visionary experiences were not only of personal relevance, but were entwined with a nodal historical moment. In late-1914 and 1915 he compiled the visions jotted in the journals, along with his additional commentary on each imaginative episode, into a clean manuscript. This manuscript was the beginning of Liber Novus.[21]

In 1915 Jung began transcribing his draft text into the illuminated calligraphic volume that would subsequently become known as the Red Book. In 1917 he compiled a further supplementary manuscript of visionary material and commentary, which he entitled "Scrutinies". This also was apparently intended for transcription into his red folio volume, the "Red Book".[22] Although Jung laboured on the decorated transcription of the corpus of manuscript material into the calligraphic folio of the Red Book for sixteen years, he never completed the task. Only approximately two-thirds of Jung's manuscript text was transcribed into the Red Book by 1930, when he abandoned further work on the detailed transcriptions.[23] The published edition of The Red Book: Liber Novus includes all of Jung's manuscript material prepared for Liber Novus, and not merely the portion of the text transcribed by Jung himself into the calligraphic folio volume.[24]

In 1957, near the end of his life, Jung spoke to Aniela Jaffé about the Red Book and the process which gave rise to it. In that interview he stated:

The years ... when I pursued the inner images, were the most important time of my life. Everything else is to be derived from this. It began at that time, and the later details hardly matter anymore. My entire life consisted in elaborating what had burst forth from the unconscious and flooded me like an enigmatic stream and threatened to break me. That was the stuff and material for more than only one life. Everything later was merely the outer classification, scientific elaboration, and the integration into life. But the numinous beginning, which contained everything, was then.[25]

In 1959, after having left the book more or less untouched for about 30 years, Jung wrote a short epilogue: "To the superficial observer, it will appear like madness."[10]

Creation and physical description

[edit]

Jung worked on his text and images in the Red Book using a calligraphic pen, multicoloured ink, and gouache paint. The text is written in German but includes quotations from the Vulgate in Latin, a few inscriptions and names written in Latin and Greek, and a brief marginal quotation from the Bhagavad Gita given in English.

The initial seven folios (or leaves) of the book—which contain what is now entitled Liber Primus (the 'First Book') of Liber Novus—were composed on sheets of parchment in a highly illuminated medieval style. However, as Jung proceeded with work on the parchment sheets, it became apparent that their surface was not holding his paint properly and that his ink was bleeding through. These first seven leaves (fourteen pages, recto and verso) now show heavy chipping of paint, as will be noted on close examination of the facsimile edition reproductions.

In 1915, Jung commissioned the folio-sized volume to be bound in crimson leather.[26] The bound volume contained approximately 600 blank pages of paper of weight and quality suitable for ink and paint. The folio-sized volume, 11.57 inches (29.4 cm) by 15.35 inches (39.0 cm), is bound in fine red leather with gilt accents. Though Jung and others usually referred to the book simply as the "Red Book", he had the top of the spine of the book embossed in gilt with the book's formal title, Liber Novus ("The New Book").

Jung subsequently interleaved the seven original parchment sheets at the beginning of the bound volume. After receiving the bound volume in 1915, he began transcribing his text and illustrations directly onto the bound pages. Over the next many years, Jung ultimately filled only 191 of the approximately 600 pages bound in the Red Book folio.[27] About a third of the manuscript material he had written was never entered into the Red Book. Inside the book there are now 205 completed pages of text and illustrations (including the loose parchment sheets), all by Jung's hand:[28] 53 full-page images, 71 pages with both text and artwork, and 81 pages entirely of calligraphic text.

The Red Book is currently held, along with other valuable and private items from Jung's archive, in a bank vault in Zurich.

Publication and display

[edit]During Jung's life, several people saw his Red Book—it was often present in his office—but only a very few individuals who were personally trusted by him had the opportunity to read it. After Jung's death in 1961, his heirs held the book as a private legacy, and refused access to it by scholars or other interested parties.[29]

After many years of careful deliberations, the estate of C. G. Jung finally decided in 2000 to allow publication of the work, and thereafter began preparations for it. The decision to publish was apparently aided by representations made by London-based scholar Sonu Shamdasani, who had already discovered substantial private transcriptions of portions of The Red Book in archival repositories.[10] Editorial work and preparation for publication were underwritten by major funding from the Philemon Foundation.

USA publishing event

[edit]In the United States, on the occasion of the publication in October 2009, the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City displayed the original book along with three of Jung's original "Black Book" journals and several other related artifacts. The exhibition was open from 7 October 2009 to 25 January 2010. The Red Book was subsequently exhibited at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles from April 11 – June 6, 2010. It formed the centre of a major display and conference at the Library of Congress from June 17 – September 25, 2010.[30]

Subsequently, The Red Book was the focus of museum displays in Zurich, Geneva, Paris, and other major cities.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Jung, Carl Gustav (2012). Shamdasani, Sonu (ed.). The Red Book (Liber Novus): A Reader's Edition. Translated by Shamdasani, Sonu; Peck, John; Kyburz, Mark (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08908-0. OCLC 822339865. Note that in this edition several footnotes are updated and typographical errors found in the original printings of the facsimile edition are corrected.

- ^ a b Jung, Carl Gustav (2020). Shamdasani, Sonu (ed.). The Black Books. Translated by Liebscher, Martin; Peck, John. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08864-9. OCLC 1135934584.

- ^ a b Owens & Hoeller (2014), p. 1.

- ^ Liber Novus, p. 221.

- ^ Liber Novus.

- ^ Historian of psychoanalysis Shamdasani gives a detailed review Jung's development and his divergence from Freud during this period in Shamdasani (2012), pp. 49–60.

- ^ Owens (2010), p. 2.

- ^ a b Storr, Anthony (1996). Feet of Clay: Saints, Sinners and Madmen, A Study of Gurus. Free Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-684-82818-9. Paul Stern made similar claims in his biography of Jung, C. G. Jung: The Haunted Prophet ISBN 978-0440547440

- ^ Shamdasani (2005), pp. 1–3: Shamdasani rebuts the assertions made by both Anthony Storr and Paul Stern about Jung's supposed "psychosis".

- ^ a b c Corbett, Sara (16 September 2009). "The Holy Grail of the Unconscious". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ On the "nocturnal work", see Liber Novus, p. 211. Jung writes in Liber Novus that during the day, "I gave all my love and submission to things, to men, and to the thoughts of this time. I went into the desert only at night. Thus can you differentiate sick and divine delusion. Whoever does the one and does without the other you may call sick since he is out of balance." Liber Novus, p. 238.

- ^ Owens (2010), p. 11.

- ^ Shamdasani offers extensive documentation about Jung's normal professional and social functioning during this period in his introduction to Liber Novus, p. 221.

- ^ Liber Novus, pp. 198–202.

- ^ Liber Novus, p. 208.

- ^ Jung, Carl Gustav (1961). Aniela Jaffe (ed.). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. pp. 178–194.

- ^ Liber Novus, p. 200.

- ^ Owens (2010), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Shamdasani explains the nature of the "Black Books", and provides high-resolution photographs of these journals in: Shamdasani (2012), pp. 63–73.

- ^ Hannah, Barbara (1976). Jung: His Life and Work. Shambhala. p. 115. ISBN 0-87773-615-4.

- ^ See Shamdasani's introduction to the Red Book: Liber Novus for detailed explanation of this enterprise: Liber Novus, pp. 198–203.

- ^ Liber Novus, pp. 331ff.

- ^ In the last three years of his life, Jung returned to his folio volume, and made an effort to finish the transcription. He found it was beyond his ability, given his advanced age. The transcription ends in mid-sentence. Liber Novus, p. 360.

- ^ See Shamdasani's "Editorial Note": Liber Novus, pp. 225–6.

- ^ Liber Novus, p. vii.

- ^ High-resolution images of the Red Book appear in Shamdasani (2012), pp. 118–9.

- ^ Shamdasani (2012), p. 119n.

- ^ Grohol, John M. (20 September 2009). "Carl Jung's Red Book". World of Psychology. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Bair, Deirdre (2003). Jung: A Biography. Little, Brown. p. 745. ISBN 0-316-07665-1.

- ^ "The Red Book of Carl G. Jung: Its Origins and Influence". Library of Congress. 17 June – 25 September 2010. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

Works cited

[edit]- Jung, Carl Gustav (2009). Shamdasani, Sonu (ed.). The Red Book: Liber Novus. Translated by Kyburz, Mark; Peck, John; Shamdasani, Sonu. Preface by Hoerni, Ulrich. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06567-1. OCLC 317919484.

- Owens, Lance S. (July 2010). "The Hermeneutics of Vision: C. G. Jung and Liber Novus". The Gnostic: A Journal of Gnosticism, Western Esotericism and Spirituality (3).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Owens, Lance S.; Hoeller, Stephan A. (2014). "C. G. Jung and the Red Book: Liber Novus". Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion (2nd ed.). Springer Publications. ISBN 978-1-4614-6085-5.

- Shamdasani, Sonu (2005). Jung Stripped Bare By His Biographers, Even. Karnac. ISBN 1-85575-317-0.

- Shamdasani, Sonu (2012). C. G. Jung: A Biography in Books. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-0-393-07367-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Corbett, Sara (20 September 2009). "The Holy Grail of the Unconscious". The New York Times Magazine.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (2017). "The Great War of the Soul: Divine and Human Madness in Carl Gustav Jung's Liber Novus". In Greisiger, Lutz; Schüler, Sebastian; van der Haven, Alexander (eds.). Religion and Madness Around 1900: Between Pathology and Self-Empowerment. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3-95650-279-8.

External links

[edit] Media related to The Red Book at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Red Book at Wikimedia Commons- C. G. Jung and The Red Book — a series of eighteen audio lectures Lectures presented by Lance S. Owens, MD

- Carl Jung's Secret Book — an NPR interview with writer Sara Corbett, author of The New York Times Magazine article about the book

- "Philemon Foundation". Philemon Foundation. Retrieved 21 September 2009.