Real-time clock

A real-time clock (RTC) is a computer clock (most often in the form of an integrated circuit) that keeps track of the current time.

Although the term often refers to the devices in personal computers, servers and embedded systems, RTCs are present in almost any electronic device which needs to keep accurate time.

Terminology

The term real-time clock is used to avoid confusion with ordinary hardware clocks which are only signals that govern digital electronics, and do not count time in human units. RTC should not be confused with real-time computing, which shares its three-letter acronym but does not directly relate to time of day.

Purpose

Although keeping time can be done without an RTC,[1] using one has benefits:

- Low power consumption[2] (important when running from alternate power)

- Frees the main system for time-critical tasks

- Sometimes more accurate than other methods

A GPS receiver can shorten its startup time by comparing the current time, according to its RTC, with the time at which it last had a valid signal.[3] If it has been less than a few hours, then the previous ephemeris is still usable.

Power source

RTCs often have an alternate source of power, so they can continue to keep time while the primary source of power is off or unavailable. This alternate source of power is normally a lithium battery in older systems, but some newer systems use a supercapacitor,[4][5] because they are rechargeable and can be soldered. The alternate power source can also supply power to battery backed RAM.[6]

Timing

Most RTCs use a crystal oscillator,[7][8] but some have the option of using the power line frequency.[9] The crystal frequency is usually 32.768 kHz,[7] the same frequency used in quartz clocks and watches. Being exactly 215 cycles per second, it is a convenient rate to use with simple binary counter circuits. The low frequency saves power, while remaining above human hearing range. The quartz tuning fork of these crystals does not change size much from temperature, so temperature does not change its frequency much.

Some RTCs use a micromechanical resonator on the silicon chip of the RTC. This reduces the size and cost of an RTC by reducing its parts count. Micromechanical resonators are much more sensitive to temperature than quartz resonators. So, these compensate for temperature changes using an electronic thermometer and electronic logic.[10]

Typical crystal RTC accuracy specifications are from ±100 to ±20 parts per million (8.6 to 1.7 seconds per day), but temperature-compensated RTC ICs are available accurate to less than 5 parts per million.[11][12] In practical terms, this is good enough to perform celestial navigation, the classic task of a chronometer. In 2011, chip-scale atomic clocks became available. Although vastly more expensive and power-hungry (120 mW vs. <1 μW), they keep time within 50 parts per trillion (5×10−11).[13]

Examples

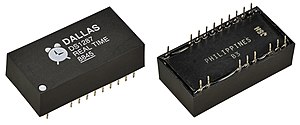

Many integrated circuit manufacturers make RTCs, including Epson, Intersil, IDT, Maxim, NXP Semiconductors, Texas Instruments, STMicroelectronics and Ricoh. A common RTC used in single-board computers is the Maxim Integrated DS1307.

The RTC was introduced to PC compatibles by the IBM PC/AT in 1984, which used a Motorola MC146818 RTC. Later, Dallas Semiconductor made compatible RTCs, which were often used in older personal computers, and are easily found on motherboards because of their distinctive black battery cap and silkscreened logo.

In newer systems, the RTC is integrated into the southbridge chip.[14]

Some microcontrollers have a real-time clock built in, generally only the ones with many other features and peripherals.

Radio-based RTCs

Some modern computers receive clock information by digital radio and use it to promote time-standards. There are two common methods: Most cell phone protocols (e.g. LTE) directly provide the current local time. If an internet radio is available, a computer may use the network time protocol. Computers used as local time servers occasionally use GPS[15] or ultra-low frequency radio transmissions broadcast by a national standards organization (i.e. a radio clock[16]).

Software-based RTCs

The following system is well-known to embedded systems programmers, who sometimes must construct RTCs in systems that lack them. Most computers have one or more hardware timers from quartz crystals or ceramic resonators with inaccurate absolute timing (more than 100 parts per million) that is very repeatable (often less than 1 ppm). Software can do the math to make these into RTCs. The hardware timer can produce a periodic interrupt, e.g. 50 Hz, to mimic a historic RTC (see below). However, it uses math to adjust it for accuracy:

time = time + rate.

When the "time" variable exceeds a constant, usually a power of two, the nominal, calculated clock time (say, for 1/50 of a second) is subtracted from "time", and the clock's timing-chain software is invoked to count fractions of seconds, seconds, etc. With 32-bit variables for time and rate, the mathematical resolution of "rate" can exceed one part per billion. The clock remains accurate because it will occasionally skip a fraction of a second, or increment by two fractions. The tiny skip is imperceptible for almost all real uses of an RTC.

The complexity with this system is determining the instantaneous corrected value for the variable "rate". The simplest system tracks RTC seconds and reference seconds between two settings of the clock, and divides reference seconds by RTC seconds to find "rate". Internet time is often accurate to less than 20 milliseconds, so 8000 or more seconds (2.2 or more hours) of separation between settings can usually divide the forty milliseconds (or less) of error to less than 5 parts per million to get chronometer-like accuracy. The main complexity with this system is converting dates and times to counts of seconds, but methods are well known.[17]

If the RTC runs when a unit is off, usually the RTC will run at two rates, one when the unit is on and another when off. This is because the temperature and power-supply voltage in each state is consistent. To adjust for these states, the software calculates two rates. First, software records the RTC time, reference time, on seconds and off seconds for the two intervals between the last three times that the clock is set. Using this, it can measure the accuracy of the two intervals, with each interval having a different distribution of on and off seconds. The rate math solves two linear equations to calculate two rates, one for on and the other for off.

Another approach measures the temperature of the crystal with an electronic thermometer, (e.g. a thermistor and ADC) and uses a polynomial to calculate "rate" about once per minute. The most common quartz crystals in a system are SC-cut crystals, and their rates over temperature can be characterized with a 3rd-degree polynomial. So, for these, the rate is measured at four temperatures. The common tuning-fork-style crystals used in watches and many RTC components have parabolic (2nd-degree) equations of temperature, and can be characterized with only three measurements. Then a linear regression can find the equation of temperature. Something like this approach might be used in commercial RTC ICs, but the actual methods of efficient high-speed manufacturing are proprietary.

Historic RTCs

Some older computer designs such as Novas and PDP-8s[18] used a real-time clock that was notable for its high accuracy, simplicity, flexibility and low cost. The computer's power supply produces a pulse at logic voltages for either each half-wave or each zero crossing of AC mains. A wire carries the pulse to an interrupt. The interrupt handler software counts cycles, seconds, etc. In this way, it can provide an entire clock and calendar.

The clock also usually formed the basis of computers' software timing chains; e.g. it was usually the timer used to switch tasks in an operating system. Counting timers used in modern computers provide similar features at lower precision, and may trace their requirements to this type of clock. (e.g. in the PDP-8, the mains-based clock, model DK8EA, came first, and was later followed by a crystal-based clock, DK8EC.)

A software-based clock must be set each time its computer is turned on. Originally this was done by computer operators. When the Internet became commonplace, network time protocols were used to automatically set clocks of this type.

In Europe, North America and some other grids, this RTC works because the frequency of the AC mains is adjusted to have a long-term frequency accuracy as good as the national standard clocks. That is, in those grids this RTC is superior to quartz clocks and less costly.

This design of RTC is not practical in portable computers or grids (e.g. in South Asia) that do not regulate the frequency of AC mains. Also it might be thought inconvenient without Internet access to set the clock.

Clockless CPUs

Some motherboards are made without real time clocks. The real time clock is omitted either out of the desire to save money (as in the Raspberry Pi system architecture) or because real time clocks may not be needed at all (as in the Arduino system architecture).

See also

- High Precision Event Timer

- IRQ 8

- Real-time clock alarm

- System time

- Timer

- Wall-clock time

- Time formatting and storage bugs

References

- ^ Ala-Paavola, Jaakko (2000-01-16). "Software interrupt based real time clock source code project for PIC microcontroller". Archived from the original on 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ Enabling Timekeeping Function and Prolonging Battery Life in Low Power Systems, NXP Semiconductors, 2011

- ^ US 5893044 Real time clock apparatus for fast acquisition or GPS signals

- ^ New PCF2123 Real Time Clock Sets New Record in Power Efficiency, futurle

- ^ Application Note 3816, Maxim/Dallas Semiconductor, 2006

- ^ Torres, Gabriel (24 November 2004). "Introduction and Lithium Battery". Replacing the Motherboard Battery. hardwaresecrets.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Application Note 10337, ST Microelectronics, 2004, p. 2

- ^ Application Note U-502, Texas Instruments, 2004, p. 13

- ^ Application Note 1994, Maxim/Dallas Semiconductor, 2003

- ^ "Maxim DS3231m" (PDF). Maxim Inc. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Highly Accurate Real-Time Clocks". Maxim Semiconductors. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Drown, Dan (3 February 2017). "RTC comparison".

- ^ "Chip Scale Atomic Clock". Microsemi. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "ULi M1573 Southbridge Specifications". AMDboard.com. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ "GPS Clock Synchronization". Spectracom. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Product: USB Radio Clock". Meinburg. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Calendrical Applications". U.S. Naval Observatory. U.S. Navy. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Digital Equipment Corp. "PDP-8/E Small Computer Handbook, 19" (PDF). Gibson Research. pp. 7–25, the DK8EA. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

External links

Media related to Real-time clocks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Real-time clocks at Wikimedia Commons