Escape room

An escape room, also known as an escape game, puzzle room, exit game, or riddle room is a game in which a team of players discover clues, solve puzzles, and accomplish tasks in one or more rooms in order to accomplish a specific goal in a limited amount of time.[1][2] The goal is often to escape from the site of the game.

Most escape games are cooperative, but competitive variants exist.[3] Escape rooms became popular in North America, Europe, and East Asia in the 2010s. Permanent escape rooms in fixed locations were first opened in Asia[4] and followed later in Hungary, Serbia, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, and South America.[5]

Definition

[edit]

Escape rooms are inspired by escape room video games – this is also the likely source of their name.[6][7] They are also referred to as "room escapes," "escape games," "exit games," or "live escapes."

In spite of the name, escaping a room may not be the main goal for the players, nor is the game necessarily confined to a single room.[8]

Gameplay overview

[edit]The participants in an escape room normally play as a cooperative team of two to ten players.[7] Games are set in a variety of fictional locations, such as prison cells, dungeons, and space stations. The player's goals and the challenges they encounter usually align with the theme of the room.[9]

The game begins with a brief introduction to the rules of the game and how to win. This can be delivered in the form of video, audio, or a live gamemaster.[2]

Players enter a room or area wherein a clock is started and they have a limited time to complete the game, typically 45 to 60 minutes. During this time, players explore, find clues, and solve puzzles that allow them to progress further in the game. Some escape rooms, especially horror-themed variants, may also include escaping from restraints such as handcuffs or zip ties.[1] Challenges in an escape room generally are more mental than physical, and it is usually not necessary to be physically fit or dexterous.[8] Different skills are required for different types of puzzles, ranging from chemistry to mathematics, geography, and a basic understanding of other subjects. Well-designed escape room puzzles don't require players to have expert knowledge in any particular field; any specialized or little-known information required to solve a puzzle should be obtainable within the room itself.

If players get stuck, there may be a mechanism in place by which they can ask for hints. Hints may be delivered in written, video, or audio form, or by a live gamemaster or actor present in the room.[10]

The players "fail" the room if they are unable to complete all of the puzzles within the allotted time, but most escape room operators strive to ensure that their customers have fun even if they don't win.[8] Players may be given different experiences depending on their success or loss in forms of "good endings" and "bad endings" within the room if they win or fail, respectively. Good endings are usually represented by either escaping "alive" within the time limit, completing the room's objective, or even stopping the threat or antagonist of the story, while bad endings usually represent the players getting "killed" by the main driving force of the story or an antagonist of the room coming to get the players once the timer has run out. Some venues allow players extra time or an expedited walk-through of the remaining puzzles.

Sometimes, teams with fast times are placed on a leaderboard, and records are kept for future teams to beat.

Game design

[edit]

Puzzle solving

[edit]Escape rooms test the problem-solving, lateral thinking ("thinking outside the box"), and teamwork skills of participants by providing a variety of puzzles and challenges that unlock access to new items or areas in the game when solved.[11]

Escape room puzzles include word games, numbers, and "arranging things into patterns"[12] such as substitution cyphers, riddles, crosswords, Sudoku, word search, and mathematics; puzzles involving physical objects such as jigsaw puzzles, matchstick puzzles, and chess; and physical activity such as searching for a hidden physical object, assembling an object, navigating mazes, or undoing a rope knot.

History

[edit]Different attractions contained elements similar to modern escape rooms and could thus be seen as precursors to the idea, including haunted houses, scavenger hunts, entertainment center 5 Wits or interactive theater (such as Sleep No More, inaugurated in 2003).[13]

The format of a room or area containing puzzles or challenges has been featured in multiple TV game shows over the years, including Now Get Out of That (1981-1984),[14] The Adventure Game (1980-86),[15] The Crystal Maze,[15] Fort Boyard and Knightmare.[16] Similar experiences can be found in interactive fiction software and escape the room video games.[17]

An additional impetus for escape rooms came from the "escape the room" genre of video games. Escape the room games, which initially began as Flash games for web browsers and then moving onto mobile apps, challenged the player to locate clues and objects within a single room.[6][18]

An early concept resembling modern escapes room was True Dungeon, which premiered at GenCon Indy in Indianapolis, USA, in July 2003.[19][20] Created by Jeff Martin (True Adventures LLC), True Dungeon had many of the same elements that people associate with escape rooms today: a live-action team-based game where players explored a physical space and cooperatively solved mental and physical puzzles to accomplish a goal in a limited amount of time. True Dungeon "focuses on problem solving, teamwork, and tactics while providing exciting sets and interactive props".[21]

Four years later, Real Escape Game (REG) in Japan was developed by 35-year-old Takao Kato,[22] of the Kyoto publishing company, SCRAP Co., in 2007.[6] It is based in Kyoto, Japan and produces a free magazine by the same name. Beyond Japan, Captivate Escape Rooms appeared in Australia and Singapore from 2011,[23] the market growing to over 60 games by 2015.[2] Kazuya Iwata, a friend of Kato, brought Real Escape Game to San Francisco in 2012.[24] The following year, Seattle-based Puzzle Break founded by Nate Martin became the first American-based escape room company.[25] Japanese games were primarily composed of logical puzzles, such as mathematical sequences or color-coding, just like the video games that inspired them.

In 2003 in Spain Differend Games opened the doors of the escape room Négone first in Getafe with "La Maquina" and then in 2005 in Madrid with "La Fuga".

Parapark, a Hungarian franchise that later operated in 20 locations in Europe and Australia, was founded in 2011 in Budapest.[6][26] The founder, Attila Gyurkovics, claims he had no information about the Japanese escape games and based the game on Mihály Csíkszentmihályi's flow theory and his job experience as a personality trainer.[27] As opposed to the Japanese precursors, in Parapark's games, players mainly had to find hidden keys or reach seemingly unattainable ones in order to advance.

In 2012, the Swiss physics professor Gabriel Palacios created a scientific escape game for his students. The game was later offered to the public under the name AdventureRooms and distributed as a franchise in twenty countries. AdventureRooms introduced scientific puzzles (e.g. hidden infrared or polarized codes) to the genre.[28]

As of November 2019, there were estimated to be over 50,000 escape rooms worldwide.[29] These can be particularly lucrative for the operators, as the upfront investment has been as low as US$7,000, while a party of 4-8 customers pay around US$25–30 per person for one hour[30] to play, potentially generating annual revenue upwards of several hundred thousand dollars.[31] As the industry has grown, start up costs have increased dramatically and so has the competition. Some customers now expect higher production values and games can cost over $50,000 to create.

Reception

[edit]

The South China Morning Post described escape rooms as a hit among "highly stressed students and overworked young professionals."[32] Sometimes players damage equipment or decorations inside the game area.[33]

The use of Hong Kong room escapes as distractions from the city's living conditions has been commented on by local journalists.[34][35]

Evolution

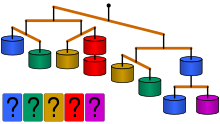

[edit]Early games consisted mainly of puzzles that were solved with paper and pencil. Some versions are digital or printable only.[36] As escape rooms became more sophisticated, physical locks were introduced that could be opened by finding combinations, hidden keys, and codes using objects found in the rooms. These ideas have evolved to include automation technology, immersive decoration,[37] and more elaborate storylines to make puzzles more interactive, and to create an experience that is more theatrical and atmospheric.[3]

Some escape rooms have begun to incorporate virtual reality elements.

Safety

[edit]

The first known fatal accident to occur in an escape room was the death of five 15-year-old girls in a fire in Koszalin, Poland, on January 4, 2019. The fire was caused by a leaky gas container inside a heater and resulted in the death of the five victims from carbon monoxide poisoning. One employee was treated for burns. According to the state firefighting service, the chief failure that led to the deaths was the lack of an effective evacuation route. Shortly after the accident, authorities ordered safety checks in escape rooms across Poland and 13 more such establishments were shut down for safety flaws as a result.[38][39]

In popular culture

[edit]Reno 911, an American comedy show, aired the episode "Escape-O-Rama Room" in August 2020.[40] Canadian comedy show Schitt's Creek aired an escape room episode, "The Bachelor Party", in March 2020. The Big Bang Theory, an American comedy, aired an escape room episode, "The Intimacy Acceleration", in 2015.[41] In 2023, the Dropout game show Game Changer aired the episode "Escape the Greenroom".

The escape room concept has also been explored in other television programs such as It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Bob's Burgers, and Harley Quinn.

In 2019, the American psychological horror film Escape Room was released in theaters, and its sequel Escape Room: Tournament of Champions came out in 2021 following several delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[42] Both films deal with a mysterious, deadly series of puzzle rooms that explore the traumatic pasts of its players. Escape Room grossed $155.7 million worldwide against a production budget of $9 million,[43] and Tournament of Champions grossed $51.8 million.[44][45]

In February 2022, the children's book Escape Room by Christopher Edge was named "Children's Book of the Week" by The Times.[46]

Escape rooms started reaching new audiences through the TikTok app.[47] Escape room companies such as Exit Game OC,[48] Breakout Games[49] and Amazing Escape Room[50] have found new customers through organic viral TikTok videos.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hall, L.E. (2021). "What Is an Escape Room?". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ a b c "Peeking Behind the Locked Door: A Survey of Escape Room Facilities" (PDF). White Paper. Retrieved 2015-05-24.

- ^ a b Hall, L.E. (2021). "The 2010s to Now: The Rise of Escape Room Games". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ "The unbelievably lucrative business of escape rooms". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Raspopina, Sasha (2015-07-23). "Great escapes: the strange rise of live-action quest games in Russia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ a b c d Hall, L.E. (2021). "The 2000s: Precursors and the Birth of Escape Rooms". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ a b Penttilä, Katriina (14 August 2018). History of Escape Games : examined through real-life-and digital precursors and the production of Spygame (Thesis). Retrieved 5 January 2019 – via www.utupub.fi.

- ^ a b c Wiemker, Markus; Elumir, Errol; Clare, Adam (November 2015). "Escape Room Games: "Can you transform an unpleasant situation into a pleasant one?"" (PDF). White Paper.

- ^ Hall, L.E. (2021). "Making Games Yourself". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ Hall, L.E. (2021). "How Hints Work". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ Hall, L.E. (2021). "Team Building and Cohesion". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ "Popular board games to try this holiday season". NPR.org. November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Hall, L.E. (2021). "The 1980s–2020s: New Ways of Looking at Shared Spaces". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ "Now Get Out of That". Labyrinth Games. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ^ a b "Prigionieri in una scatola?". Io Gioco (in Italian). No. supplement to The Games Machine n. 346. 2017. p. 20.

- ^ Hall, L.E. (2021). "The 1970s–1990s: A Game Vocabulary for the Public". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ Hall, L.E. (2021). "Types of Rooms". Planning Your Escape. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781982140342.

- ^ Suellentop, Chris (June 4, 2014). "In Escape Rooms, Video Games Meet Real Life". The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Sjoberg, Lore (2008-08-13). "True Dungeon Lures Would-Be Dragon Slayers". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "True Dungeon: True Dungeon Timeline: 2003 Info (1/7)". new.truedungeon.com. Retrieved 2019-08-22.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "True Dungeon - Real Dungeon. Real Props. Real Cool". 2007-06-30. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ Corkill, Edan (2009-12-20). "Real Escape Game brings its creator's wonderment to life". The Japan Times Online. Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ^ Marinho, Natalie (2012-01-31). "The Real Escape Game in Singapore". recognitionpattern. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (21 June 2014). "Real-life 'escape rooms' are new US gaming trend". CNBC. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Geek of the Week: There's no escaping it — Puzzle Break's Nate Martin created his dream startup". GeekWire. 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Bence, Gyulai (2011-09-09). "ParaPark: tökéletes élmény egy romkocsma pincéjében" [ParaPark: A Perfect Experience in the Basement of a Pub's Ruins] (in Hungarian). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ^ Kummer, Krisztián (March 2013). "Room escape games the latest craze in Budapest". Budapest Business Journal.

- ^ Hess, Stéphane (September 10, 2013). "Physik: Kriminelle Energie erwünscht" (PDF). "BILDUNG SCHWEIZ" (Education Switzerland). pp. 24–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ "International Escape Room Markets analysis| The Logic Escapes Me". thelogicescapesme.com. November 2019. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ "For $28, this Alpharetta business will lock you inside a room". myajc. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ French, Sally; Shaw, Jessica Marmor (July 20, 2015). "The unbelievably lucrative business of escape rooms". MarketWatch. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ "Real-life escape games offer respite from daily stresses". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- ^ "Rooms with a different kind of view". China Daily USA. Archived from the original on 2013-09-26. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- ^ "Real-life escape games offer respite from daily stresses|". South China Morning Post. 2013-02-13. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ^ "Hong Kong Thrill Seekers think their way to freedom|". CBC News. 2013-02-22. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- ^ "Escape Room FAQ". www.fisherhuntz.com. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ "Immersion - UK Escape Game Wiki". www.escaperoomuk.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ "Escape room fire kills five teenagers in Poland". BBC News. 2019-01-04.

- ^ "Man charged after 5 girls killed in escape room fire in Poland". Global News. 2019-01-06.

- ^ "Reno 911! S07E14 - Escape-O-Rama Room (TVShow Time)". TV Time. August 24, 2020. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "'The Intimacy Acceleration'". EW.com. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 26, 2021). "Sony Moves Up Escape Room 2 To Summer, Lands On Same Date As Studio's Cinderella". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Escape Room (2019)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Escape Room: Tournament of Champions (2021)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Escape Room: Tournament of Champions". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ O'Connell, Alex (29 January 2022). "Escape Room by Christopher Edge review — gamers will love this mad, intense thriller". The Times. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Akhtar, Saima (2022-05-13). "Viral TikTok shows group performing 'ritual' in Manchester escape room". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ Law, Peih-Gee (2024-01-12). "REPOD Special Release Bonus Episode from S6E3: Going Viral with Christine Barger". Room Escape Artist. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Escape Room Worker Uses Metal Gear Solid Sneaking Skills To Help Unwitting Players". Kotaku. 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Man locks escape room employees in building and leaves clues on how to escape". UNILAD. 2023-10-02. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

External links

[edit] Media related to Escape rooms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Escape rooms at Wikimedia Commons