Raymond A. Palmer

Raymond A. Palmer | |

|---|---|

Raymond A. Palmer circa 1930 | |

| Born | Raymond Arthur Palmer August 1, 1910 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | (aged 67) Portage, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer, editor |

| Genre | Science fiction |

Raymond Arthur Palmer (August 1, 1910 – August 15, 1977[1]) was an American author and editor, best known as editor of Amazing Stories from 1938 through 1949, when he left publisher Ziff-Davis to publish and edit Fate Magazine, and eventually many other magazines and books through his own publishing houses, including Amherst Press and Palmer Publications. In addition to magazines such as Mystic, Search, and Flying Saucers, he published or republished numerous spiritualist books, including Oahspe: A New Bible, as well as several books related to flying saucers, including The Coming of the Saucers, co-written by Palmer with Kenneth Arnold. Palmer was also a prolific author of science fiction and fantasy stories, many of which were published under pseudonyms.

Personal life

According to Bruce Lanier Wright, "Palmer was hit by a truck at age seven and suffered a broken back." An unsuccessful operation on Palmer's spine stunted his growth (he stood about four feet tall), and left him with a hunchback.

Palmer found refuge in science fiction, which he read voraciously. He rose through the ranks of science fiction fandom and is credited, along with Walter Dennis, with editing the first fanzine, The Comet, in May, 1930.[2]

Career

Throughout the 1930s, Palmer would have many of his stories published in several science fiction magazines of the era. When Ziff-Davis acquired Amazing Stories in 1938, editor T. O'Conor Sloane resigned and production was moved to Chicago. On the recommendation of popular author Ralph Milne Farley, the editorship was offered to Palmer. In 1939, Palmer began a companion magazine to Amazing Stories titled Fantastic Adventures, which lasted until 1953.

When Ziff-Davis moved its magazine production from Chicago to New York City in 1949, Palmer resigned and, with Curtis Fuller, another Ziff-Davis editor who did not want to leave the midwest, founded Clark Publishing Co.[3]

Science fiction magazines

As an editor, Palmer tended to favor adventurous, fast-moving space opera-type stories. His tenure at Amazing Stories was notable for his purchase of Isaac Asimov's first professional story, "Marooned Off Vesta".

Palmer was also known for his support of the long-running and controversial Shaver Mystery stories, a series of stories by Richard Sharpe Shaver. Palmer's support of the truth of Shaver's stories (which maintained that the world is dominated by insane inhabitants of the hollow earth), was controversial in the science fiction community. It is unclear whether Palmer believed the Shaver stories to be true, or if he was just using the stories to sell magazines. Palmer asked other writers to do stories in the Shaver genre, the most notable being Rog Phillips.

Palmer began his own science fiction publishing ventures while working for Ziff-Davis, eventually leaving the company to form his own publishing house, Clark Publishing Company, which was responsible for the titles Imagination and Other Worlds, among others. None of these magazines achieved the success of Amazing Stories during the Palmer years, but Palmer published Space World magazine until his death.

Paranormality magazines

In 1948, Palmer and Curtis Fuller co-founded Fate, which covered divination methods, Fortean events, belief in the survival of personality after death, predictive dreams, accounts of ghosts, mental telepathy, archaeology, flying saucer sightings, cryptozoology, alternative medicine, warnings of death, and other paranormal topics, many contributed by readers.

Curtis Fuller and his wife Mary took full control of Fate in 1955, when Palmer sold his interest in the venture. The magazine has continued in publication under a series of editors and publishers to the present day.

Another paranormal magazine Palmer created along the line of Fate was Mystic magazine, which after about two years of publication became Search magazine. [citation needed]

In the 1970s, Palmer also published Ray Palmer's News Letter which was combined into another of his publications called Forum in March 1975.[4][unreliable source?]

Flying Saucers magazine

In the first issue of Fate, Palmer published Kenneth Arnold's report of "flying discs." Arnold's sighting marked the beginning of the modern UFO era, and his story propelled the fledgling Fate to national recognition. Through Fate, Palmer was instrumental in popularizing belief in flying saucers. This interest led him to establish the magazine Flying Saucers.

Spiritual publications

Palmer's avid interest in spirituality and alternative explanations of reality was reflected in his choice of publications. His interest in the Oahspe Bible, led him on a 15-year search for a copy of the original 1882 edition published by Oahspe Publishing Assoc., New York and London. Although a later edited and revised edition was published in 1891 and reprinted over the years, the original 1882 Oahspe Bible was not available until Palmer republished a facsimile of it in 1960. It is often referred to as "The Palmer Edition" or "The Green Oahspe" among Oahspe readers. He continued to publish and reprint later editions to which he added an index and editor's notes. Oahspe was reported by the spiritualist medium John B. Newbrough to have come as automatic writing through his hands on the newly invented typewriter.

FBI File: CIA UFO Connection

Ray Palmer was investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation beginning early 1953 to mid 1954, after being falsely accused of spreading Soviet Communist propaganda in several Mystic Magazine articles. Chicago FBI Special Agents interviewed Palmer after he ran a story, "Venusians Walk Our Streets," by science fiction author, Frank M. Vest. The story claimed the FBI laboratories were researching a mystery metal from Venus mentioned in the article. The FBI did a records search, and found that their laboratories had never received any such metal and that no such research was being performed. When confronted with this falsehood, Palmer claimed that he did not catch the FBI reference and the "mystery metal," in his final edit, but quickly apologized for the mistake, and even offered to run a retraction. During the course of the interview Palmer did confess to Special Agents that he was however, involved in forwarding "Letters To The Editor," accounts of Flying Saucers to the Central Intelligence Agency office in Chicago. He stated that the magazine received some 50 letters a week regarding flying sauser sightings, and that he forwarded the most feasible accounts to the Chicago office of the Central Intelligence Agency. The FBI released Ray Palmer's secret and confidential file on 22 June, 2018,under the Freedom Of Information Act(FOIA).[5]

Tributes

The secret identity of DC Comics superhero the Atom – introduced by science fiction writer Gardner Fox in 1961 – is named after Palmer.

A newer edition of Oahspe as a tribute edition to Ray Palmer was published in 2009 titled Oahspe - Raymond A. Palmer Tribute Edition.

In September 2013, Palmer was posthumously named to the First Fandom Hall of Fame in a ceremony at the 71st World Science Fiction Convention.[6]

In 2013, Tarcher/Penguin published a biography of Palmer called The Man From Mars and written by Fred Nadis.

Palmer is also the subject of Richard Toronto's 2013 book, War over Lemuria: Richard Shaver, Ray Palmer and the Strangest Chapter of 1940s Science Fiction, which attempts to give a detailed history of the Shaver Mystery and its two main proponents.

Bibliography

Short stories

- The Time Ray of Jandra, Wonder Stories (June 1930)

- The Man Who Invaded Time, Science Fiction Digest (October 1932)

- Escape from Antarctica, Science Fiction Digest (Juneau 1933)

- The Girl from Venus, Science Fiction Digest (September 1933)

- The Return to Venus, Fantasy Magazine (May 1934)

- The Vortex World, Fantasy Magazine (1934)

- The Time Tragedy, Wonder Stories (December 1934)

- Three from the Test-Tube, Wonder Stories (1935)

- The Symphony of Death, Amazing Stories (December 1935)

- Matter Is Conserved, Astounding Science-Fiction (April 1938)

- Catalyst Planet, Thrilling Wonder Stories (August 1938)

- The Blinding Ray, Amazing Stories (August 1938)

- Outlaw of Space, Amazing Stories (August 1938)

- Black World (Part 1 of 2), Amazing Stories (March 1940)

- Black World (Part 2 of 2), Amazing Stories (April 1940)

- The Vengeance of Martin Brand (Part 1 of 2), Amazing Stories (August 1942)

- The Vengeance of Martin Brand (Part 2 of 2), Amazing Stories (September 1942)

- King of the Dinosaurs, Fantastic Adventures (October 1945)

- Toka and the Man Bats, Fantastic Adventures (February 1946)

- Toka Fights the Big Cats, Fantastic Adventures (December 1947)

- In the Sphere of Time, Planet Stories (Summer 1948)

- The Justice of Martin Brand, Other Worlds Science Stories (July 1950)

- The Hell Ship, Worlds of If (March 1952)

- Mr. Yellow Jacket, Other Worlds (June 1951)

- I Flew in a Flying Saucer (Part 1 of 2), Other Worlds Science Stories (October 1951)

- I Flew in a Flying Saucer (Part 2 of 2), Other Worlds Science Stories (December 1951)

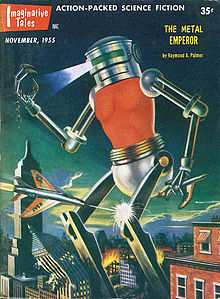

- The Metal Emperor, Imaginative Tales (November 1955)

Nonfiction

- The Coming of the Saucers (with Kenneth Arnold) (1952)

- The Secret World (with Richard Shaver) (1975)

See also

References

- ^ Contemporary Authors, Volume 111, Gale 1984. According to this work, Palmer died following a series of strokes.

- ^ Moskowitz, Sam; Joe Sanders (1994). "The Origins of Science Fiction Fandom: A Reconstruction". Science Fiction Fandom. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 17–36.

- ^ Harry Warner, Jr. All Our Yesterdays, pgs 75-78.

- ^ Files of astronomer Donald Menzel

- ^ https://documents.theblackvault.com/documents/fbifiles/paranormal/raymondpalmer-fbi1.pdf

- ^ Glyer, Mike (September 3, 2013). "2013 First Fandom Hall of Fame". File 770. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

External links

- Works by Raymond A. Palmer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Raymond A. Palmer at the Internet Archive

- The Positively True Story of Kenneth Arnold - Part Four at Saturday Night Uforia

- Raymond A. Palmer at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Shavertron magazine about Ray Palmer involvement in the Shaver Mystery

- Fear Down Below: The Curious History of the Shaver Mystery, by Bruce Lanier Wright

- Fate magazine official site

- I Flew In A Flying Saucer A PDF scan of an 'Other Worlds' Sci Fi magazine story from 1951

- The Cosmos Project - Bringing to life the Cosmos sci-fi serial novel from 1933

- 1910 births

- 1977 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- American science fiction writers

- Science fiction editors

- Amazing Stories

- American male short story writers

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- People associated with ufology

- Forteana

- Pseudoscience literature