Score voting

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Score voting, sometimes called range voting, is an electoral system for single-seat elections. Voters give each candidate a numerical score, and the candidate with the highest average score is elected.[1] Score voting includes the well-known approval voting (used to calculate approval ratings), but also lets voters give partial (in-between) approval ratings to candidates.[2]

Usage

[edit]Political use

[edit]Historical

[edit]A crude form of score voting was used in some elections in ancient Sparta, by measuring how loudly the crowd shouted for different candidates.[3][4][5] This has a modern-day analog of using clapometers in some television shows and the judging processes of some athletic competitions.

Beginning in the 13th century, the Republic of Venice elected the Doge of Venice using a multi-stage process with multiple rounds of score voting. This may have contributed to the Republic's longevity, being partly responsible for its status as the longest-lived democracy in world history.[6][7] Score voting was used in Greek legislative elections beginning in 1864, during which time it had a many-party system; it was replaced with party-list proportional representation in 1923.[8]

According to Steven J. Brams, approval was used for some elections in 19th century England.[9]

Current

[edit]Score voting is used to elect candidates who represent parties in Latvia's Saeima (parliament) in an open list system.[10]

The selection process for the Secretary-General of the United Nations uses a variant on a three-point scale ("Encourage", "Discourage", and "No Opinion"), with permanent members of the United Nations Security Council holding a veto over any candidate.[11][12]

Proportional score voting was used in Swedish elections in the early 20th century, prior to being replaced by party-list proportional representation. It is still used for local elections.

| Governor Candidates |

Score each candidate by filling in a number (0 is worst; 9 is best) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Candidate A | → | ⓿①②③④⑤⑥⑦⑧⑨ |

| 2: Candidate B | → | ⓪①②③④⑤⑥⑦⑧❾ |

| 3: Candidate C | → | ⓪①②③④⑤⑥❼⑧⑨ |

In 2018, Fargo, North Dakota, passed a local ballot initiative adopting approval voting for the city's local elections, becoming the first US city to adopt the method.[13][14][15]

Score voting is used by the Green Party of Utah to elect officers, on a 0–9 scale.[16]

Non-political use

[edit]Members of Wikipedia's Arbitration Committee are elected based on a three-point scale ("Support", "Neutral", "Oppose").[17]

Non-governmental uses of score voting are common, such as in Likert scales for customer satisfaction surveys and mechanism involving users rating a product or service in terms of "stars" (such as rating movies on IMDb, products at Amazon, apps in the iOS or Google Play stores, etc.). Judged sports such as gymnastics generally rate competitors on a numeric scale.

A multi-winner proportional variant called Thiele's method or reweighted range voting is used to select five nominees for the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects rated on a 0–10 scale.[18]

Example

[edit]

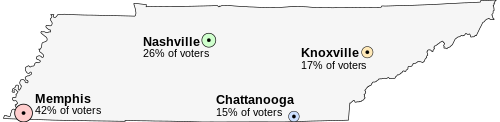

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Suppose that 100 voters each decided to grant from 0 to 10 points to each city such that their most liked choice got 10 points, and least liked choice got 0 points, with the intermediate choices getting an amount proportional to their relative distance.

| Voter from/ City Choice |

Memphis | Nashville | Chattanooga | Knoxville | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 420 (42 × 10) | 0 (26 × 0) | 0 (15 × 0) | 0 (17 × 0) | 420 |

| Nashville | 168 (42 × 4) | 260 (26 × 10) | 90 (15 × 6) | 85 (17 × 5) | |

| Chattanooga | 84 (42 × 2) | 104 (26 × 4) | 150 (15 × 10) | 119 (17 × 7) | 457 |

| Knoxville | 0 (42 × 0) | 52 (26 × 2) | 90 (15 × 6) | 170 (17 × 10) | 312 |

Nashville, the capital in real life, likewise wins in the example.

For comparison, note that traditional first-past-the-post would elect Memphis, even though most citizens consider it the worst choice, because 42% is larger than any other single city. Instant-runoff voting would elect the 2nd-worst choice (Knoxville), because the central candidates would be eliminated early (and Chattanooga voters preferring Knoxville above Nashville). In approval voting, with each voter selecting their top two cities, Nashville would win because of the significant boost from Memphis residents.

Properties

[edit]Score voting allows voters to express preferences of varying strengths, making it a rated voting system.

Score voting is not vulnerable to the less-is-more paradox, i.e. raising a candidate's rating can never hurt their chances of winning. Score also satisfies the participation criterion, i.e. a candidate can never lose as a result of voters turning out to support them. Score voting satisfies independence of irrelevant alternatives, and does not tend to exhibit spoiler effects.

It does not satisfy the Condorcet criterion, i.e. the method does not always agree with the majority rule. However, when voters all vote strategically, basing their votes on polling or past election results, the majority-preferred candidate will win.[19]

Strategy

[edit]Ideal score voting strategy for well-informed voters is generally identical to their optimal approval voting strategy; voters will want to give their least and most favorite candidates a minimum and a maximum score, respectively. The game-theoretical analysis shows that this claim is not fully general, but holds in most cases.[20] Another strategic voting tactic is given by the weighted mean utility theorem, maximum score for all candidates preferred compared to the expected winners weighted with winning probability and minimum score for all others.[21]

Papers have found that "experimental results support the concept of bias toward unselfish outcomes in large elections." The authors observed what they termed ethical considerations dominating voter behavior as pivot probability decreased. This would imply that larger elections, or those perceived as having a wider margin of victory, would result in fewer tactical voters.[22]

How voters precisely grade candidates is a topic that is not fully settled, although experiments show that their behavior depends on the grade scale, its length, and the possibility to give negative grades.[23]

STAR voting (Score Then Automatic Runoff) is a variant proposed to address some concerns about strategic exaggeration in score voting. Under this system, each voter may assign a score (from 0 to the maximum) to any number of candidates. Of the two highest-scoring candidates, the winner is the one most voters ranked higher.[24] The runoff step was introduced to mitigate the incentive to exaggerate ratings in ordinary score voting.[25][26]

Advocacy

[edit]Albert Heckscher was one of the earliest proponents, advocating for a form of score voting he called the "immanent method" in his 1892 dissertation, in which voters assign any number between -1 and +1 to each alternative, simulating their individual deliberation.[27][28][29]

Currently, score voting is advocated by The Center for Election Science.[citation needed] Since 2014, the Equal Vote Coalition advocates a variant method (STAR) with an extra second evaluation step to address some of the criticisms of traditional score voting.[30][31]

See also

[edit]- Borda count

- Cardinal voting

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- Consensus decision-making

- Decision making

- Democracy

- Implicit utilitarian voting

- Utilitarian social choice rule

- Majority judgment — similar rule based on medians instead of averages

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Score Voting". The Center for Election Science. 2015-05-21. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Simplified forms of score voting automatically give skipped candidates the lowest possible score for the ballot they were skipped. Other forms have those ballots not affect the candidate's rating at all. Those forms not affecting the candidates rating frequently make use of quotas. Quotas demand a minimum proportion of voters rate that candidate in some way before that candidate is eligible to win.

- ^ Baujard, Antoinette; Igersheim, Herrade; Lebon, Isabelle; Gavrel, Frédéric; Laslier, Jean-François (2014-06-01). "Who's favored by evaluative voting? An experiment conducted during the 2012 French presidential election" (PDF). Electoral Studies. 34: 131–145. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.11.003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2019-12-22.

voting rules in which the voter freely grades each candidate on a pre-defined numerical scale. .. also called utilitarian voting

- ^ James S. Fishkin: The Voice of the People: Public Opinion & Democracy, Yale University Press 1995

- ^ Girard, C. (2010). "Going from Theory to Practice: The Mixed Success of Approval Voting". In Laslier, Jean-François; Sanver, M. Remzi (eds.). Handbook on Approval Voting. Studies in Choice and Welfare. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 15–17. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02839-7_3. ISBN 9783642028380.

- ^ Stille, Alexander (2001-06-02). "Adding Up the Costs of Cyberdemocracy". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ Lines, Marji (1986). "Approval Voting and Strategy Analysis: A Venetian Example". Theory and Decision. 20 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1007/BF00135090. S2CID 121512308.

- ^ Mowbray, Miranda; Gollmann, Dieter (July 2007). Electing the Doge of Venice: analysis of a 13th Century protocol (PDF). IEEE Computer Security Foundations Symposium. Venice, Italy. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Mavrogordatos, George Th. (1983). Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece 1922–1936. University of California Press. pp. 351–352.

- ^ Brams, Steven J. (April 1, 2006). The Normative Turn in Public Choice (PDF) (Speech). Presidential Address to Public Choice Society. New Orleans, Louisiana. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2010. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "14. SAEIMAS VĒLĒŠANAS". sv2022.cvk.lv. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "The "Wisnumurti Guidelines" for Selecting a Candidate for Secretary-General" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- ^ Tharoor, Shashi (October 21, 2016). "The inside Story of How I Lost the Race for the UN Secretary-General's Job in 2006". OPEN Magazine. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ One of America's Most Famous Towns Becomes First in the Nation to Adopt Approval Voting Archived November 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, accessed November 7, 2018

- ^ Moen, Mike (June 10, 2020). "Fargo Becomes First U.S. City to Try Approval Voting". Public News Service. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ Piper, Kelsey (November 15, 2018). "This city just approved a new election system never tried before in America". Vox. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ "Utah Green Party Hosts Dr. Stein; Elects New Officers". Independent Political Report. 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

Using the following Range Voting System, the Green Party of Utah elected a new slate of officers

- ^ "Wikipedia:Arbitration Committee Elections December 2017". Wikipedia. 2018-03-28.

- ^ "89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS OF MERIT" (PDF). 2016. RULE TWENTY-TWO SPECIAL RULES FOR THE VISUAL EFFECTS AWARD.

Five productions shall be selected using reweighted range voting to become the nominations for final voting for the Visual Effects award.

- ^ Laslier, J.-F. (2006) "Strategic approval voting in a large electorate", IDEP Working Papers No. 405 (Marseille, France: Institut d'Économie Publique)

- ^ Nunez, Matias; Laslier, Jean-François (2014). "Preference intensity representation: strategic overstating in large elections" (PDF). Social Choice and Welfare. 42 (2): 313–340. doi:10.1007/s00355-013-0728-0. S2CID 5738643.

- ^ Approval Voting, Steven J. Brams, Peter C. Fishburn, 1983

- ^ Feddersen, Timothy; Gailmard, Sean; Sandroni, Alvaro (2009). "Moral Bias in Large Elections: Theory and Experimental Evidence". The American Political Science Review. 103 (2): 175–192. doi:10.1017/S0003055409090224. JSTOR 27798496. S2CID 55173201.

- ^ Baujard, Antoinette; Igersheim, Herrade; Lebon, Isabelle; Gavrel, Frédéric; Laslier, Jean-François (2014). "How voters use grade scales in evaluative voting" (PDF). European Journal of Political Economy. 55: 14–28. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.09.006.

- ^ "Equal Vote Coalition". Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ "Score Runoff Voting: The New Voting Method that Could Save Our Democratic Process". IVN.us. 2016-12-08. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ "Strategic SRV? - Equal Vote Coalition". Equal Vote Coalition. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ Lagerspetz, Eerik (2014-06-01). "Albert Heckscher on collective decision-making". Public Choice. 159 (3–4): 327–339. doi:10.1007/s11127-014-0169-z. ISSN 0048-5829. S2CID 155023975.

- ^ Eerik, Lagerspetz (2015-11-26). Social choice and democratic values. Cham. p. 109. ISBN 9783319232614. OCLC 930703262.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Heckscher, Albert Gottlieb (1892). Bidrag til Grundlæggelse af en Afstemningslære: om Methoderne ved Udfindelse af Stemmeflerhed i Parlamenter (in Danish).

- ^ "About The Equal Vote Coalition". Equal Vote Coalition. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ^ "STAR Voting campaign". Retrieved 2019-09-02.

External links

[edit]- The Center for Range Voting and its simplified introductory homepage

- The Center for Election Science includes an article on Score Voting

- Equal Vote Coalition, which promotes a STAR voting, a variant of score voting, in the United States

- Simulation of various voting models for close elections Article by Brian Olson.

- Mechanic, Michael; William Poundstone (2007-01-02). "The verdict is in: our voting system is a loser". Mother Jones. The Foundation for National Progress. Archived from the original on 2008-02-09. Retrieved 2008-02-04.