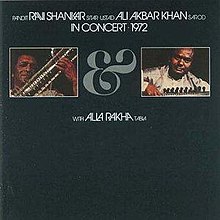

In Concert 1972

| In Concert 1972 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Live album by | |

| Released | 22 January 1973 (US) 13 April 1973 (UK) |

| Recorded | 8 October 1972 |

| Venue | Philharmonic Hall, New York |

| Genre | Hindustani classical |

| Length | 1:41:59 |

| Label | Apple |

| Producer | George Harrison, Zakir Hussain, Phil McDonald |

In Concert 1972 is a double live album by sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar and sarodiya Ali Akbar Khan, released in 1973 on Apple Records. It was recorded at the Philharmonic Hall, New York City, in October 1972, and is a noted example of the two Hindustani classical musicians' celebrated jugalbandi (duet) style of playing. With accompaniment from tabla player Alla Rakha, the performance reflects the two artists' sorrow at the recent death of their revered guru, and Khan's father, Allauddin Khan. The latter was responsible for many innovations in Indian music during the twentieth century, including the call-and-response dialogue that musicians such as Shankar, Khan and Rakha popularised among Western audiences in the 1960s.

The album features three ragas, including "Raga Sindhi Bhairavi", which Ali Akbar Khan had previously interpreted on his landmark 1955 recording Music of India. In Concert 1972 has received critical acclaim; Ken Hunt of Gramophone magazine described it as a "sometimes smouldering, sometimes fiery, masterpiece" and "the living, fire-breathing embodiment of one of the greatest partnerships ever forged in Hindustani [classical music]".[1]

In Concert 1972 was produced by George Harrison, Zakir Hussain and Phil McDonald. It was the final Shankar-related release on the Beatles' Apple label, following his and Harrison's work together on Raga and The Concert for Bangladesh. Apple issued In Concert 1972 on CD in 1996 and 2004, reuniting the 50-minute "Raga Manj Khamaj", which had previously been split over two LP sides.

Background

[edit]

Along with other leading figures in the field of Hindustani classical music such as Pannalal Ghosh and Annapurna Devi,[3] Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar trained in the Maihar gharana under Khan and Devi's father, the teacher and multi-instrumentalist Allauddin Khan.[4][5] Known as "Baba",[6] the latter is recognised as one of the great Indian classical music innovators of the twentieth century,[4][7] having composed up to 600 pieces of music and been responsible for modernising two of its most important string instruments – the sitar and the sarod.[8] Author Peter Lavazzoli credits Baba's various contributions as having "shaped ... much of what the West knows as Indian classical music" via Shankar and Khan's subsequent work.[9]

Of the two musicians, Khan, as a master sarodya, was the first to achieve international recognition,[10] with a visit to New York that culminated in his 1955 album Music of India: Morning and Evening Ragas.[11][12] The latter was the first album of Indian classical music,[11] and its success led to Shankar recording his debut, Three Ragas, in London the following year.[13] While highly regarded as solo artists, Shankar and Khan's duets, known as jugalbandi, were similarly acclaimed from the 1950s onwards.[14] Music critic Ken Hunt writes of the "tigerish potential for male (sarod) and female (sitar) dialogue" in their jugalbandi combination.[11] Another Baba legacy was the jawab-sawal (call-and-response) interplay between solo instruments and the twin hand-drum tabla – a dialogue that Shankar, especially, popularised with Western rock audiences, through his and tabla player Alla Rakha's performances at Monterrey and Woodstock in the late 1960s.[15]

Compared to the more traditional musical path adopted by Khan,[12] Shankar experimented with genres outside Indian classical music and increasingly associated with Western artists, including George Harrison and Philip Glass.[16][17] Born in East Bengal (now part of Bangladesh), Khan joined Shankar on stage at Madison Square Garden, New York, in August 1971 for the Concert for Bangladesh, organised by Harrison.[18][19] Just over a year afterwards, on 8 October 1972, Shankar and Khan were recorded at another New York venue, the Philharmonic (now Avery Fisher) Hall, accompanied again by Rakha.[20] Shankar often commented on the warm reception afforded him by audiences in America,[21] where New York had been the first Western city to embrace Indian music.[22][23][nb 1]

As at the Bangladesh shows, there was a poignancy to this 1972 performance, following the death of Allauddin Khan in September that year.[1][24] As their music guru, Baba had remained a revered figure in their lives,[25] and a man considered a saint in his home town of Maihar.[26][nb 2] In My Music, My Life, Shankar's 1968 autobiography, he writes admiringly of Baba "follow[ing] a way of life that was a beautiful fusion of the best of both Hinduism and Islam", and being similarly broadminded in his musical vision by "[leading] us away from the confines of narrow specialization that prevailed in our music".[29][nb 3] The ensuing duet at the Philharmonic Hall was a passionate musical exchange between Shankar and Khan, a performance that "far surpasses a tribute frozen in time", according to Hunt.[1]

Recording

[edit]Friends, we dedicate this evening's recital to late Ustad Allauddin Khan ... He died little over a month [ago], and his loss to our music is something which cannot ever be repaired, because he was the greatest musician, the greatest instrumentalist, that we had.[33][34]

In a role that he had introduced[35] as an ambassador for Indian classical music,[36] Shankar first addressed the New York audience, to explain what the loss of Allauddin Khan meant to Indian music.[1] He then introduced the first piece, "Raga Hem Bihag", as "one of [Baba's] creations".[33] As with all the selections, the lead performers received the composer's credit, however,[20] in keeping with Hindustani tradition, which allows for greater improvisation on a recognised composition compared with the more structured Karnatak tradition.[37]

Providing the drone-like accompaniment behind Shankar and Khan during the concert were two tambura players, named as Ashoka and Susan on the album credits.[38] Lavezzoli writes of Shankar's longstanding association with his tabla player that Rakha was "the ideal partner", given the drummer's broad training.[39] Continuing Baba's efforts to elevate tabla from its previous, secondary status, Shankar allowed the drums more space in his performances,[40] ensuring that the tabla became recognised as a solo instrument.[41]

"Hem Bihag", an evening raga, was followed by a night raga, "Manj Khamaj",[33] a piece that had appeared on Shankar's 1970 live album At the Woodstock Festival.[42] The final selection was a morning raga, "Sindhi Bhairavi".[33] Khan had recorded this piece as side one of Music of India, and Shankar similarly included it on The Sounds of India, a 1957 album that Lavezzoli describes as "his own counterpart" to Khan's debut release.[43][nb 4]

The Philharmonic Hall recording became In Concert 1972, made up of the three ragas spread over four LP sides and totalling over 140 minutes of music.[20] An Apple Records release via Shankar's friendship with Harrison, the double album was produced in London by Harrison midway through sessions for his Living in the Material World album.[48] Harrison's co-producers were Rakha's son[49] Zakir Hussain, and sound engineer Phil McDonald.[50]

Release

[edit]Apple Records issued In Concert 1972 in January 1973 in the United States (as Apple SVBB 3396),[51] and three months later in Britain (as Apple SAPDO 1002).[20] Billboard magazine carried an Apple trade ad with a tagline beginning: "Within the small community of Brilliantly Gifted Musicians there exists an even smaller world of Masters. Two of these masters recently joined together in concert …"[52]

The double album appeared at the same time as a flurry of other Apple releases,[53] some of them two-record sets also, in the case of Yoko Ono's Approximately Infinite Universe and the Beatles compilations 1962–1966 and 1967–1970.[54][55] Despite such an output of product, the label was being wound down from this point on.[56] In Concert 1972 was the final Shankar-related release on Apple Records, following his Joi Bangla EP and Raga film soundtrack[18] and the Concert for Bangladesh triple album, all issued in 1971.[57]

Reissue

[edit]By the time In Concert 1972 was available in the UK, in April 1973,[20] Shankar, Harrison, Rakha and Khan's sarod-playing son Aashish were working in Los Angeles on the Shankar Family & Friends album.[58][59] The latter, which would be a Dark Horse Records release,[60] was remastered and reissued in 2010 as part of the Collaborations box set,[61][62] at the same time as Shankar's East Meets West Music reissued the equally rare Raga documentary and soundtrack album.[63][64] In Concert 1972 was not included in these reissue projects, but it was released on CD as part of Apple's 1996–97 repackaging campaign.[65] The 2004 two-CD version reunited the two halves of "Raga Manj Khamaj".[66]

Reception and legacy

[edit]On release, Billboard's reviewer described the trio of Shankar, Khan and Rakha as "[t]he greatest all-star line-up of raga players" and suggested that the album's "fiery and hypnotic" music could make it "the best-selling raga record of recent years".[67] Record Mirror said that the LP sleeve's statement regarding a "meeting of souls" was an appropriate one, adding that the performance featured "some quite astonishing technical achievements" by the musicians.[68]

Rough Guides' world music guidebook lists In Concert 1972 among its "very selective highlights" of all Shankar's releases, and writes of the live album: "Pyrotechnics and profundity recorded in New York, matching sitar and sarod in Hindustani music's greatest jugalbandi."[69] In a piece written not long after the death of Ali Akbar Khan in June 2009, MusicTraveler website described the album as "absolutely mesmerising".[70] Some commentators have written that Khan's sarod playing surpassed that of his father,[12][14] whose more emotional temperament led to an inconsistent quality in his live performances.[71] Noting the reverence afforded Baba for his contributions to the genre, Rough Guide remarks on such comparisons: "While it is considered unpardonable even to whisper it, many consider [Khan] the more elevating player."[72]

Reviewing the Apple CD in June 1997, Ken Hunt enthused in Gramophone magazine:

This is the living, fire-breathing embodiment of one of the greatest partnerships ever forged in Hindustani (Northern Indian) classical music. Their sarod–sitar brotherhood had begun under their guru during the 1940s. By the 1950s their combination of the robust, steel-clad sarod and the delicate sitar was highly acclaimed and in 1972 theirs was undoubtably the hottest ticket in Hindustani heaven … Two musicians pouring their hearts out for their guru: that is the most succinct description of this sometimes smouldering, sometimes fiery, masterpiece. Few Hindustani reissues – or new releases – will match its white-hot heat of creativity this year."[1]

Following Shankar's death in December 2012, David Fricke of Rolling Stone included In Concert as one of five recommended recordings by the sitarist, writing: "This wonderful recording comes from a show at New York's Philharmonic Hall with a dream team: Ali Akbar Khan on sarod and Alla Rakha on tabla. One of the three pieces, 'Raga – Manj Khamaj,' totals almost an hour, enabling you to get much closer than on most Shankar albums of the period, to the natural extension and patient exploration of an Indian classical-music evening."[66] In his book The Ambient Century, Mark Prendergast describes the double album as a "classic" and "one of the best examples of sitar, sarod, tabla and tambura interplay ever recorded".[73]

Track listing

[edit]All selections by Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan.

Side one

- "Raga Hem Bihag" – 25:17

Side two

- "Raga Manj Khamaj (Part One)" – 26:16

Side three

- "Raga Manj Khamaj (Part Two)" – 25:06

Side four

- "Raga Sindhi Bhairavi" – 25:20

Personnel

[edit]- Ravi Shankar – sitar

- Ali Akbar Khan – sarod

- Alla Rakha – tabla

- Ashoka – tambura

- Susan – tambura

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In an interview with Rolling Stone magazine in 1968, when he was playing another series of concerts at the Philharmonic, Shankar expressed surprise that acceptance had been harder to achieve in Britain, since that country "really should have been the first one to have been conscious of Indian music because of its relation to India for almost 150 to 160 years".[23]

- ^ Confusion surrounds the exact year of Allauddin Khan's birth,[27] with some sources claiming he was aged 109 when he died.[28]

- ^ During that same year, 1968, Shankar saw Baba for the final time,[30] a visit recorded in the 1971 documentary Raga.[31][32] Shankar later revealed that their relationship had been a difficult one, after his marriage to Annapurna Devi, Baba's daughter, began to fail.[30]

- ^ More recently, Shankar had adapted "Sindhi Bhairavi" for the Second Movement of Concerto for Sitar & Orchestra,[44] his 1971 collaboration with conductor André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra.[16] Indian music's most popular morning raga,[45] "Sindhi Bhairavi" also appears in another Shankar–Khan jugalbandi performance on From Dusk to Dawn,[46] a Shankar compilation released in 2000.[47]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Ken Hunt, "Review: Ravi Shankar Ali Akbar Khan, In Concert 1972", Gramophone, June 1997, p. 116.

- ^ Shankar, My Music, My Life, p. 65.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 33, 52.

- ^ a b Craig Harris, "Allauddin Khan", AllMusic (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ Massey, pp. 142–43.

- ^ Shankar, My Music, My Life, pp. 58, 60.

- ^ Arnold, pp. 203–04.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 30–31, 54.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 16.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b c Ken Hunt, "Ustad Ali Akbar Khan: Sarod maestro who played with Ravi Shankar and appeared at the Concert for Bangladesh", The Independent, 25 June 2009 (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ a b c William Grimes, "Ali Akbar Khan, Sarod Virtuoso, Dies at 87", The New York Times, 19 June 2009 (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 61.

- ^ a b World Music: The Rough Guide, p. 76.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 38, 208.

- ^ a b Reginald Massey, "Ravi Shankar obituary", The Guardian, 12 December 2012 (retrieved 1 November 2013).

- ^ Prendergast, p. 206.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli, pp. 187, 190.

- ^ Reginald Massey, "Obituary: Ali Akbar Khan", The Guardian, 22 June 2009 (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ a b c d e Castleman & Podrazik, p. 122.

- ^ Shankar, My Music, My Life, p. 99.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 58, 99.

- ^ a b Sue C. Clark, "Ravi Shankar: The Rolling Stone Interview", Rolling Stone, 9 March 1968 (retrieved 25 November 2013).

- ^ World Music: The Rough Guide, pp. 77, 78.

- ^ Shankar, My Music, My Life, pp. 58, 65, 85.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 15, 33.

- ^ World Music: The Rough Guide, p. 77.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Shankar, My Music, My Life, pp. 59, 62.

- ^ a b Shankar, Raga Mala, p. 221.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 184.

- ^ "Howard Worth discussing Raga (2010)" on YouTube (retrieved 1 November 2013).

- ^ a b c d Booklet accompanying In Concert 1972 reissue (Apple Records, 1996; produced by George Harrison, Zakir Hussain & Phil McDonald).

- ^ "Ravi Shankar & Ali Akbar Khan in concert 1972" on YouTube (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ World Music: The Rough Guide, p. 65.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 17, 57.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 3, 21.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 203.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 105.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, p. 310.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 34, 38, 106.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar At the Woodstock Festival", AllMusic (retrieved 25 November 2013).

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 1–2, 59, 61.

- ^ Album credits, Ravi Shankar: In Celebration box set (Angel/Dark Horse, 1995; produced by George Harrison & Alan Kozlowski).

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 4–5.

- ^ World Music: The Rough Guide, p. 78.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar – From Dusk to Dawn (The Raga Collection)", Discogs (retrieved 27 November 2013).

- ^ Spizer, pp. 254, 341.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 107.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 122, 203.

- ^ Spizer, p. 341.

- ^ Apple Records trade ad, Billboard, 3 February 1973, p. 27 (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ Schaffner, p. 158.

- ^ Badman, pp. 89, 94–95.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 121, 122–23.

- ^ Leng, p. 140.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 239–40, 341.

- ^ Badman, pp. 94, 98.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 195.

- ^ Badman, p. 133.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, "George Harrison and Ravi Shankar Box Set 'Collaborations' Is a Labor of Love for Me", Spinner, 18 October 2010 (archived version from 2 January 2011; retrieved 26 October 2013).

- ^ Dan Forte, "Ravi Shankar and George Harrison Collaborations", Vintage Guitar, February 2011 (retrieved 13 August 2014).

- ^ News: "8/15/10 Raga DVD", eastmeetswest.com, 15 August 2010 (archived version retrieved 22 October 2013).

- ^ Jeff Kaliss, "Ravi Shankar Raga: A Film Journey into the Soul of India", Songlines, 26 November 2010, p. 85 (archived version from 10 July 2011; retrieved 18 November 2017).

- ^ "Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan in Concert 1972: Releases", AllMusic (retrieved 26 November 2013).

- ^ a b David Fricke, "From Monterey Pop to Carnegie Hall: The Best Recordings of Ravi Shankar", rollingstone.com, 13 December 2012 (retrieved 26 October 2013).

- ^ "Album Reviews", Billboard, 10 February 1973, p. 64 (retrieved 31 October 2013).

- ^ "Mirrorpick-LPs", Record Mirror, 26 May 1973, p. 24.

- ^ World Music: The Rough Guide, pp. 75, 78.

- ^ MusicTraveler, "Ravi Shankar & Ali Akbar Khan – In Concert 1972" Archived 11 July 2012 at archive.today, 18 September 2009 (retrieved 14 February 2012).

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 53.

- ^ World Music: The Rough Guide, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Prendergast, p. 207.

Sources

[edit]- Alison Arnold, South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent, Part 1 [Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 5], Taylor & Francis (London, 2000; ISBN 0-8240-4946-2).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- Olivia Harrison, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Abrams (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4).

- Peter Lavezzoli, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 0-8264-2819-3).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Reginald Massey, The Music of India, Abhinav Publications (New Delhi, NCT, 1996; ISBN 81-7017-332-9).

- Mark Prendergast, The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Moby – The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age, Bloomsbury (New York, NY, 2003; ISBN 1-58234-323-3).

- Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY, 1978; ISBN 0-07-055087-5).

- Ravi Shankar, My Music, My Life, Mandala Publishing (San Rafael, CA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-60109-005-8).

- Ravi Shankar, Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar, Welcome Rain (New York, NY, 1999; ISBN 1-56649-104-5).

- Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Solo on Apple Records, 498 Productions (New Orleans, LA, 2005; ISBN 0-9662649-5-9).

- World Music: The Rough Guide (Volume 2: Latin and North America, Caribbean, India, Asia and Pacific), Rough Guides/Penguin (London, 2000; ISBN 1-85828-636-0).