Chennai Central railway station

Chennai Central | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Main entrance of Chennai Central | |||||||||

| General information | |||||||||

| Other names | M.G.R. Chennai Central, Chennai Central, Madras Central | ||||||||

| Location | Grand Western Trunk Road, Kannappar Thidal, Periyamet, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, 600003 | ||||||||

| Coordinates | 13°04′57″N 80°16′30″E / 13.0825°N 80.2750°E | ||||||||

| Elevation | 3.465 metres (11.37 ft) | ||||||||

| Owned by | Government of India | ||||||||

| Operated by | Southern Railway zone of Indian Railways | ||||||||

| Line(s) | Chennai–New Delhi Chennai–Howrah Chennai–Mumbai Chennai–Bengaluru | ||||||||

| Platforms | 17 (12 Main station + 5 Chennai Suburban Terminal) | ||||||||

| Tracks | 17 | ||||||||

| Connections | MTC, Suburban Rail, MRTS, Dr. M.G.R. Chennai Central Metro. | ||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||

| Structure type | Romanesque[1] | ||||||||

| Parking | Available | ||||||||

| Accessible | |||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||

| Status | Functioning | ||||||||

| Station code | MAS | ||||||||

| Zone(s) | Southern Railway zone | ||||||||

| Division(s) | Chennai | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| Opened | 1873[2] | ||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1959 (first) 1998 (second) | ||||||||

| Electrified | 1931[3] | ||||||||

| Previous names |

| ||||||||

| Passengers | |||||||||

| 530,000/day[4] (200 trains (including 46 pairs of express/mail trains)/day[4]) | |||||||||

| Services | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

Chennai Central (officially Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central Railway Station, formerly Madras Central) (station code: MAS[5]), is an NSG–1 category Indian railway station in Chennai railway division of Southern Railway zone.[6] It is the main railway terminus in the city of Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. It is the busiest railway station in South India and one of the most important hubs in the country. It is connected to Moore Market Complex railway station, Chennai Central metro station, Chennai Park railway station, and Chennai Park Town railway station. It is about 1.8 km (1.1 mi) from the Chennai Egmore railway station. The terminus connects the city to major cities of India, including Bangalore, Kolkata, Mumbai, and New Delhi, and different parts of India.

The century-old building of the railway station, designed by architect George Harding, is one of the most prominent landmarks in Chennai.[7] The station is also a main hub for the Chennai Suburban Railway system. It lies adjacent to the current headquarters of the Southern Railway and the Ripon Building. During the British Raj, the station served as the gateway to South India, and the station is still used as a landmark for the city and the state.

The station was renamed twice: first to reflect the name change of the city from Madras to Chennai in 1998, it was renamed from Madras Central to Chennai Central, and then to honour the AIADMK founder and the former chief minister of Tamil Nadu M. G. Ramachandran, it was renamed as Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central Railway Station on 5 April 2019.[8]

About 550,000 passengers use the terminus every day, making it the busiest railway station in South India.[9] Along with Chennai Egmore and Coimbatore Junction, the Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central is among the most profitable stations of the Southern Railway.[10] As per a report published in 2007 by the Indian Railways, Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central and Secunderabad Junction were awarded 183 points out of a maximum of 300 for cleanliness, the highest in the country.[11]

History

[edit]Marking the initial days of the railways in the Indian subcontinent, the Madras Railway Company began to network South India in 1856. The first station was built at Royapuram, which remained the main station at that time. Expansion of the Madras Railways network, particularly the completion of the Madras–Vyasarpadi line,[13] called for a second station in Madras, resulting in Madras Central coming into being.[7]

Madras Central was built in 1873 at Park Town around the slopes of Periamet, then known as Narimedu or Hog's Hill,[14] as a second terminus to decongest the Royapuram harbour station, which was being used for port movements. The station was built on the open grounds that had once been called John Pereira's Gardens, belonging to Joao Pereira de Faria (John Pereira), a Portuguese merchant in the port town of Negapatam (present-day Nagapattinam) who settled in Madras in 1660. The garden had a house used by Pereira for rest and recreation. Having fallen into disuse, the garden had become a gaming den, with cockfighting being the favourite sport at that time, until when the Trinity Chapel was built nearby in 1831 and the Railways moved into the area in the 1870s.[13]

In 1907, Madras Central was made the Madras Railway Company's main station.[15] The station gained prominence after the beach line was extended further south in the same year, and Royapuram was no longer a terminus for Madras.[16] All trains were then terminated at Madras Central instead. The Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway Company was formed in 1908 and took over the Central station from the Madras Railway Company.[15] The station's position was further strengthened after the construction of the headquarters of the Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway (erstwhile Madras Railway and now known as the Southern Railway) adjacent to it in 1922.[17]

Madras Central was part of South Indian Railway Company during the British rule. The company was established in 1890 and was initially headquartered in Trichinopoly. Egmore railway station was made its northern terminus in 1908.[15] It was then shifted to Madurai and later to Madras Central. With the opening of the Egmore railway station, plans were first made of linking Madras Central and Egmore, which was later dropped.[15] The company operated a suburban electric train service for Madras city from May 1931 onwards in the Madras Beach–Tambaram section.[18] In 1959, additional changes were made to the station.[7] Electrification of the lines at the station began in 1979, when the section up to Gummidipoondi was electrified on 13 April 1979. The lines up to Tiruvallur were electrified on 29 November 1979 while the tracks along Platforms 1 to 7 were electrified on 29 December 1979.[19]

Expansion

[edit]In the 1980s, the Southern Railway required land for expansion of the terminus and was looking for the erstwhile Moore Market building located next to the terminus. In 1985, when the market building caught fire and was destroyed, the structure was transferred to the Railways by the government, and the Railways built a 13-storied complex to house the suburban terminus and railway reservation counter. The land in front of the building was made into a car park.[20] Following the renaming of the city of Madras in 1996, the station became known as Chennai Central. Due to increasing passenger movement, the main building was extended in 1998 with the addition of a new building on the western side with a similar architecture to the original. After this duplication of the main building, the station had 12 platforms.[7] Capacity at the station was further augmented when the multi-storeyed Moore Market Complex was made a dedicated terminus with three separate platforms for the Chennai Suburban Railway system. In the 1990s, when the IRCTC was formed, modular stalls came up and food plazas were set up.[21]

In 2005, the buildings were painted a light brown colour, but concurring with the views of a campaign by the citizens of Chennai and also to retain the old nostalgic charm, they were repainted in their original brick-red colour.[22] The station is the first in India to be placed on the cyber map.[7]

Location

[edit]

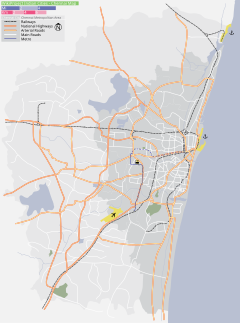

The terminus lies on the southern arm of the diamond junction of Chennai's railway network, where all the lines of the Chennai Suburban Railway meet. The terminus is located about 19 km from Chennai International Airport. The main entrance is located at Park Town at the intersection of the arterial Poonamallee High Road, Pallavan Salai, and Wall Tax Road between the People's Park and the Southern Railways headquarters. The station premises is located on the grounds known as the Kannappar Thidal in Periyamet, on either side of the Buckingham Canal, formerly known as Cochrane's Canal, which separates the main station and the suburban terminus. Wall Tax Road runs alongside the station on the eastern side. There are two other entrances on the eastern and western sides of the complex. The eastern entrance on Wall Tax Road leads to platform no. 1,[23] and the western entrance lies at the entrance of the suburban terminus. The station is connected with the Park railway station and the Government General Hospital, both located across the road, by means of subways. During the building of the Chennai Metro the connection from Chennai Park to Chennai Central is by means of a steel footbridge.

Layout

[edit]Architecture

[edit]Built in the Gothic Revival style, the original station was designed by George Harding and consisted of four platforms[24][25] and a capacity to accommodate 12-coach trains.[21] It took another five years for the work to be completed, when the station was modified further by Robert Fellowes Chisholm with the addition of the central clock tower, Travancore 'caps' on the main towers, and other changes.[26] The redesign was eventually completed in 1900.[7] The main building, a combination of Gothic and Romanesque styles[7] has been declared as a heritage building.[27] The clock tower with the flagstaff, the tallest of the towers of the main building, has four faces and reaches a height of 136 ft.[28] It is set to chime every quarter of an hour and every hour.[7][21]

The station has a platform area of 51,182 square metres (excluding the suburban station building) and the total building area of the main station is 14,062 square metres.[29]

Platforms

[edit]

Chennai Central is a terminal station with bay platforms. The average length of railway tracks in the station is 600 metres.[30] The entire complex has 17 platforms to handle long-distance trains with 5 platforms exclusively for suburban trains. The total length of the station is about 950 m. The main building has 12 platforms and handles long-distance trains. The complex for suburban trains is popularly known as the Moore Market complex. There is a platform 2A between platforms 2 and 3; it is used to handle short-length trains like the Chennai Rajadhani Express, Vijayawada Jan Shatabdi Express, Bengaluru Shatabdi Express, Mysuru Shatabdi Express and the Gudur Passenger. The 13-storied annexe building, the Moore Market Complex building, has 5 platforms and handles north- and westbound suburban trains.

Chennai Central used to have trains with special liveries until the early 1990s. The Brindavan Express used to have green livery with a yellow stripe running above and below the windows; Nilgiri Express (popularly known as the Blue Mountain Express) had blue livery. All trains now have the standard blue livery (denoting air-braked bogies). Notable exceptions include the Rajadhani, Shatabdi and the Jan Shatabdi expresses. The Sapthagiri Express, Tirupati Express has a vivid green/cream livery combination with a matching WAM4 6PE locomotive from Arakkonam (AJJ) electric locomotive shed.

Chennai Central, unlike many other major railway stations in India, is a terminus. The next station to Chennai Central, the Basin Bridge Junction, is the railway junction where three different lines meet.

As of 2015, all platforms except 2A platforms, in the station were able to accommodate trains with 24 coaches. Platform 2A is the shortest of all platforms in the station and can accommodate trains with 18 coaches.[31] Chennai Central is the only station that has a platform numbered 2A. Though it was built actually for delivering water and goods to the station staff, the Shatabdi Express now starts from here.

Bridge

[edit]Bridge No.7 across the Buckingham Canal connects the terminus with the railway yards and stations to the north. The bridge, measuring 33.02 m in length and carrying six tracks, acts as the gateway to the terminus. The bridge was originally resting on cast iron screw pile. Following the 2001 accident of Mangalore Chennai Mail killing 57 passengers, Southern Railway started replacing all bridges resting on screw piles, and the bridge was replaced with a new RCC box bridge resting on well foundation in September 2010, with ancillary works getting completed by March 2011.[32]

Traffic

[edit]On an average, 89 trains are operated daily from the station of which 12 have 24 coaches.[31] About 400 trains arrive and depart at the station daily, including about 86 pairs of mail/express trains, in addition to 857 suburban trains handled by the five platforms at the station's suburban terminus.[33][34][35] About 400,000 passengers use the terminus every day,[9] in addition to 20,000 visitors accompanying them to see-off or receive them,[21] generating a revenue of ₹6,590,214,293 (US$79 million) as of 2012–2013, making it the top revenue-generating station of the Southern Railway. There is likely to be around 180,000 passengers in the station at a given point.[21] As of 2015–16, the main station alone (excluding the suburban station) has an average passenger footfall of 95,560 per day. Passenger earnings in the same period amounted to ₹ 8947.4 million. The station managed 491 trains a day. It has been projected that the number of passengers using the main station per day in the next 40 years will be 650,000.[29]

The terminus also faces traffic problems. Often, express trains and EMU services that arrive at the Basin Bridge Junction in time have to be detained for non-availability of platforms at Chennai Central. Blocking of lines is a daily challenge owing to the traffic.[36]

Services

[edit]Chennai Central railway station is a major transit point for shipment of inland and sea fish in South India through trains. The terminus handles fish procured from Kasimedu which is sent to Kerala and sea fish from the West Coast which is brought to Chennai and ferried to West Bengal. As of 2012, on an average, the terminus handles transportation of 200 boxes of fish, each comprising 50 kilograms (110 lb) to 70 kilograms (150 lb) of consumable fish.[37] The station also handles 5,000 postal bags daily.[38]

Facilities

[edit]

The station has bookshops, restaurants, accommodation facilities, internet browsing centres, and a shopping mall. The main waiting hall can hold up to 1,000 people.[39] In spite of being the most important terminus of the region, the station lacks several facilities such as coach position display boards.[40] The main concourses too have long exhausted their capacity to handle the increasing passenger crowd.[41] There are passenger operated enquiry terminals and seven touch-screen PNR status machines in the station.[42] The station has three split-flap timing boards,[43] electronic display boards and plasma TVs that mention train timings and platform number.[35][44] A passenger information center in the station has been upgraded with "Spot your Train" live train display facility, information kiosks and passenger digital assistance booths.[33] The terminus, however, has only 10 toilets, which is inadequate to its 350,000 passengers.[45]

In September 2018, a 5,000-litre drinking water vending reverse osmosis plant was commissioned in the station.[46]

As of 2008, there were 607 licensed railway porters in Chennai Central.[47] Four-seater battery operated vehicles are available to cater to the needs of the elderly and the physically impaired.[48]

On 26 September 2014, Chennai Central became the first in the country to get free Wi-Fi connectivity. The facility is being provided by RailTel, a public sector telecom infrastructure provider.[49]

Emergency medical care

[edit]In November 2012, a public interest writ petition was filed in the Madras High Court citing the lack of a full-fledged emergency medical care centre at the terminus.[50] Further to this, the Southern Railway invited expression of interest from several hospitals in the city to establish a medical care centre.[51][52]

On 15 April 2013, a new emergency medical care centre was opened. The centre has three beds, two doctors on duty and another on standby, four nurses, a paramedic team, and a round-the-clock ambulance. The centre is equipped with oxygen cylinders, an ECG, a defibrillator and resuscitation equipment. The terminus is the first railway station in the country to have facilities of an ambulance.[53]

Parking

[edit]The station has parking facilities for more than 1,000 two-wheelers.[54] About 1,000 cars are parked in the standard car park every day. Since March 2008, a premium car park facility for 80 cars in addition to its regular car park is functioning at the station. The cement-concrete-paved premium parking is located between the Moore Market reservation complex and the station's main building.[55][56] However, the station still faces parking problems. About 3,000 taxis arrives at the station every day.[57]

Maintenance

[edit]According to the Railway sources, as of July 2012, Chennai Central was 180 short of the sanctioned 405 maintenance employees, including mechanical, electrical and general maintenance, required for cleaning the interiors and exteriors of trains and undertaking routine mechanical and electrical maintenance of trains.[58] Contracts for cleaning the station has been awarded for a period of three years from 2010 for a value of ₹ 43.1 million.[59] In 2007, the number of dustbins in the station was 28.50 per 10,000 passengers.[11]

On average, about 51 train units depart and arrive at the station from different parts of the country every day. Of the 102 trains, a 12 are sent during the day and another 7 at night to the Basin Bridge Train Care Centre[60] for primary maintenance, which involves complete exterior and interior cleaning and total mechanical and electrical overhaul. The rest of the trains go through secondary maintenance or 'other-end attention' at the depot or 'turn back train attention' at Chennai Central itself. Secondary maintenance includes filling water, while the third is the 'other-end attention', in which the train, especially the toilets, is cleaned. The fourth category of trains, such as Sapthagiri Express and Pallavan Express, are turn-back trains, which arrive and leave in a short time from Chennai Central after toilet-cleaning and water-filling is done right at the terminus platform.[58]

The station has been divided into two zones for mechanised cleaning contracts.[61] As of 2008, Chennai Central had about 30 sanitary workers employed on a contractual basis in Zone I (platforms 1 to 6). Zone II (platforms 7 to 12) was cleaned by close to 40 railway employees.[30]

Yards and sheds

[edit]Train care centre

[edit]

A broad-gauge coach maintenance depot, called the Basin Bridge Train Care Centre, is located at the northern side of the terminus, where trains of 18 to 24 coaches are checked, cleaned and readied for its next trip after they return from round trips.[62][63] It is the largest train care centre under the Southern Railway where 30 pairs of trains are inspected every day. The yard has 14 pit lines, each 3-ft deep, to inspect undercarriage of trains, but only two lines can accommodate 24-coach trains. The rest are designed to park 18-coach trains. Five to six people are allotted to each train. As of 2012, the centre has 3,500 employees, a shortage of about 400.[63]

Water accumulated in pit lines are let out into the Buckingham Canal by means of drainage channels. However, as the yard is located in a basin area, water does not drain quickly enough.[64] In addition, the centre faces pests and other hygiene issues too.[65][66]

Electric trip shed

[edit]The terminus has an electric locomotive trip shed, the Basin Bridge electric locomotive trip shed, located north of the train care centre. It is one of the five locomotive trip sheds of the Southern Railway.[67] To lessen load on the shed, an additional electric trip shed has been created at Tondiarpet, which also serves as a crew change point for freights.[68]

Goods shed

[edit]The terminus has a goods shed attached to it at Salt Cotaurs.[69]

Renovation

[edit]

Chennai Central gets renovation after 2010, is undertaken by the building division of the Southern Railway with the technical assistance provided by the Chennai Circle of Archaeological Survey of India. The work is carried out to ensure the original character of the building is maintained. The Station building has maroon colour since its inception in 1873.[70]

In February 2019, as part of the Railway Ministry's plan to install flag masts at 75 major stations in the country, a 100-foot flag mast was installed at the front of the main building of the station at a cost of ₹ 1.5 million. Weighing around 2 tonnes, the mast is made of galvanised iron pipes. The mast is one of the tallest in the city. The polyester-and-cotton flag is 60-ft wide and weighs around 9.5 kg, and can be hoisted both manually and electronically.[71]

Connectivity

[edit]

Chennai Central is a hub for suburban trains. Suburban lines originating from Chennai Central include West North Line, North Line, and West Line.[72] Chennai Park suburban station is in proximity to the station, thus facilitating connectivity to Tambaram/Chengalpet/Tirumalpur routes through South Line and South West Line. Chennai Central can be directly reached from all suburban stations and MRTS stations in and around Chennai (except Washermanpet and Royapuram) either through its own MMC Complex for suburban trains or through the nearby Park suburban station or the Park Town MRTS station. Currently, there is only one direct suburban train that plies from Chennai Beach Junction to Chennai Central via Washermanpet and Royapuram, and hence there is no frequent direct connectivity for these two stations to Chennai Central. The Chennai Park Town MRTS station is close to Chennai Central station.

An underground metro station of the Chennai Metro namely Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central metro station serves as the hub. It is one of the two metro stations where Corridor I (Blue Line) (Airport–Tiruvottiyur) of the project will intersect with Corridor II (Green Line) (Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central Metro–St. Thomas Mount via Egmore, Puratchi Thalaivi Dr. J. Jayalalithaa CMBT Metro). The metro station, is at a depth of 25 metres (82 ft), is the largest of all metro stations in the city with an area of over 70,000 square metres (750,000 sq ft).[73] The station will act as a transit point for passengers from the Central, Park Town, and Park railway stations.[74] It is estimated that more than 100,000 commuters will utilise the station daily.[73]

Chennai Central is connected to the Chennai Mofussil Bus Terminus and other parts of the city by buses operated by the Metropolitan Transport Corporation,[75] by means of separate bus lanes near the main entrance, close to the concourse. There are prepaid auto and taxi stands at the station premises.[76] However, only 30 autorickshaws are presently attached to the prepaid counter parking, as Chennai Metro Rail has acquired its parking area for station construction.[77]

The terminus is connected to the Park railway station and the Government General Hospital by two subways on either side. The two subways, which are one of the first in the city, are used by thousands of commuters day round.[78] Nevertheless, jaywalking prevails as a substantial number of commuters prefer crossing the road,[79] at times resulting in accidents.[78]

The terminus is connected with the Egmore station, the other most important terminus of the city, by a circuitous and congested route covering a distance of 11.2 km via Chennai Beach. There was initially a proposal to connect the two termini by means of an elevated section with double-line broad-gauge electrified track with two elevated platforms at Chennai Central, at the cost of ₹ 930 million, which would cut the distance to 2.5 km.[80][81] The project, approved on 8 April 2003 and initially aimed to be completed by 2005, was later scrapped owing to the expected rate of return on the project being only 1 to 2 per cent,[82] poor soil conditions on the Poonamallee High Road,[83] and other issues.[84]

Environmental impact

[edit]The portion of the Buckingham canal running near the terminus and beneath Pallavan Salai is covered for 250 m, which makes the task of maintaining the canal difficult. After being desilted in 1998, the covered stretch of the canal near the terminus was cleaned in September 2012. Garbage is dumped into the canal via the openings near the Chennai Central premises. An estimated 6,000 cubic meters of silt was removed from the 2-m-deep canal.[85]

Incidents

[edit]On 14 August 2006, a major fire broke out in Chennai Central, completely destroying a bookshop.[86]

On 29 April 2009, a suburban EMU train from Chennai Central Suburban terminal was hijacked by an unidentified man, who rammed it into a stationary goods train at the Vyasarpadi Jeeva railway station, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) northwest of Chennai Central. Four passengers were killed and 11 were injured.[87] The train, which was scheduled to depart at 5:15 am, started at 4:50 am instead.[88] The train was moving with a speed of 92 km per hour with 35 passengers on board at the time of collision.[89]

On 6 August 2012, a man hailing from Nepal perched atop the clock tower of the station's main building, creating a commotion. He was later safely persuaded back down the tower by the City Police and Southern Railway officials.[28]

On 1 May 2014, the station witnessed two low-intensity blasts in two coaches S4 and S5 of the stationary Guwahati–Bengaluru Cantt. Superfast Express, killing one female passenger and injuring at least fourteen.[90][91]

In April 2020, all trains were cancelled till 30 September, except Chennai Central - New Delhi Rajdhani Express due to COVID-19.[92][93]

Security

[edit]In a first of its kind for the railways, a bomb disposal squad of the railway protection force, equipped with state-of-the-art gadgets imported at a cost of over ₹ 2.5 million, was inaugurated at Chennai Central in May 2002. The squad functions round the clock and its personnel were trained at the National Security Guard Training Centre at Maneswar and the Tamil Nadu Commando School.[94] In 2009, following the train accident at the Vyasarpadi Jeeva railway station, surveillance cameras were installed at the suburban terminus platforms. A security boundary wall 200 m long was erected along platform 14 to check unauthorised persons entering the station. Two security booths were planned, one each at the main terminus and the suburban terminus.[95] A government railway police (GRP) station is located on the first floor at the western end,[96] headed by a DSP and two inspectors.[97]

In 2009, 39 CCTV cameras were installed in the premises along with a control room.[98] In 2012, about 120 CCTV cameras are to be installed in Chennai Central.[99] In April 2012, the GRP and the Railway Protection Force (RPF) together launched a helpline known as Kaakum karangal (literally meaning 'Protecting hands'). This involved dividing the terminus into six sectors and deploying 24 police personnel for security.[100]

On 15 November 2012, Integrated Security System (ISS) was launched at the station, which comprises sub-systems such as CCTV surveillance system with 54 IP-based cameras, under-vehicle scanning system (UVSS) for entries and exits, and personal and X-ray baggage screening system. In addition, explosive detection and disposal squad have been deployed. The sub-system will be integrated by networking and monitored at the centralised control rooms. Existing CCTV network of suburban platforms has also been integrated to this system.[99][101][102]

Future

[edit]In 2004, a second terminal was planned near the Moore Market Complex, with six platforms to be constructed in the first phase of the project and four platforms each in the second and third phases. For additional infrastructure, the goods yard at Salt Cotaurs will be closed to provide more pit line and stabling line facilities for the new terminal.[36]

In 2007, the Railway Board declared a plan to develop the terminus into a world-class one at a cost of ₹200 million (US$2.4 million),[103] along with two other stations (Thiruvananthapuram Central and Mangalore Central),[104] and a high-level committee was formed in 2009 to expedite the project at a total cost of ₹1,000 million (US$12 million).[105] The plan included creating multi-level platforms where express and suburban trains could arrive and depart from the same complex.[104] However, the project is yet to begin.[106]

In June 2012, the first skywalk in Chennai connecting Chennai Central, Park Railway Station and Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital was planned at a cost of ₹200 million (US$2.4 million).[107] It will be 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) long, linking the station with nine points, including Evening Bazaar, Government Medical College and Ripon Buildings on Poonamallee High Road.

In February 2013, as part of a national initiative to eliminate ballast tracks at major stations, washable aprons—ballast-less tracks or tracks on a concrete bed—were installed along the entire length of tracks of platforms 3, 4 and 5 at the terminus. Washable aprons that are already present for a few metres in some of the platforms at the terminus will be extended, viz. 30 metres (98 ft) on platform 3, 200 metres (660 ft) on platform 4, and 50 metres (160 ft) on platform 5, while new ones will be built on platforms with ballast tracks.[108]

Chennai Central is among the 23 stations in the country that will be privatised as part of redevelopment under the BFOT (Build, Finance, Operate, Transfer) scheme. More passengers amenities will be provided on a 1.545-acre plot of land adjacent to the Moore Market Suburban complex allotted for commercial exploitation. Additional space for operational purposes, including the station master's room, passenger information centre, movement control room, Railway Protection Force control room containing closed circuit television (CCTV) cameras, Government Railway Police station, and Travelling Ticket Examiner chart room, covering a total of 2,873.76 square metres will be built.

The developer will maintain the station premises for 15 years, while the lease period of the additional land and aerial space to be developed will be 45 years.[29]

In 2017, the state government proposed to build a commercial square called the Central Square in the around the station.[109][110][111]

Renaming

[edit]On 6 March 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced at the National Democratic Alliance political rally, which was held in Kancheepuram in the presence of then Railways Minister Piyush Goyal that the iconic station will be renamed after the AIADMK founder and the former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu M. G. Ramachandran.[112][113]

On 5 April 2019, the station was officially renamed "Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central Railway Station."[8]

The name is currently India's longest and the world's second-longest name for a railway station after Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch in Wales.[114]

In popular culture

[edit]

Chennai Central railway station is one of the most prominent landmarks in the city that is often featured in movies and other pop culture in the region. The station has been used in numerous Indian novels and film and television productions over the years. Many films and television programs have been filmed at the station, including:

- Cochin Express (1967) (Malayalam)[115]

- No.20 Madras Mail (1990) (Malayalam)

- Kadhal Kottai (1996) (Tamil)

- Mudhalvan (1999) (Tamil)

- Kushi (2000) (Tamil)

- Roja Kootam (2002) (Tamil)

- Madrasapattinam (2010) (Tamil)

- Siruthai (2011) (Tamil)

- Thodari (2016) (Tamil)

- Bigil (2019) (Tamil)

The station has been poetised by Vijay Nambisan in his 1988 award-winning poem 'Madras Central' published in 1989. The poem is regarded as a modern classic.[116][117]

In 2009, the Department of Posts featured Chennai Central in a postal stamp.[118]

See also

[edit]- Railway stations in Chennai

- Transport in Chennai

- Architecture of Chennai

- Heritage structures in Chennai

References

[edit]- ^ "Origin and development of Southern Railway" (PDF). Shodhganga. p. 6. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "IR History: Early Days – I". IRFCA. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "Electric Traction-I". IRFCA. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ a b Anbuselvan, B. (27 February 2023). "Chennai Central becomes India's first 'silent' railway station". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Station Code Index" (PDF). Portal of Indian Railways. Centre For Railway Information Systems. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "Southern Railway List of Stations As on 01.04.2023 (Category-Wise)" (PDF). Portal of Indian Railways. Centre For Railway Information Systems. 1 April 2023. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kurian, Nimi (18 August 2006). "Long history of service". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b M, Manikandan (5 April 2019). "Chennai Central railway station renamed after AIADMK founder MGR". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Central station lacks drinking water facility". Deccan Chronicle. Chennai. 6 September 2012. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Southern Railway". Yatra.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Cleanliness and Sanitation on Indian Railways" (PDF). Report No.6 of 2007. Yatra.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Madras Series A: Central Station". TuckDB. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ a b "The Railway of the South". The Hindu. Chennai. 5 March 2003. Archived from the original on 16 November 2003. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Sriram, V. (23 February 2015). "A brief history of the General Hospital – a Chennai landmark". Madras Heritage and Carnatic Music. V. Sriram. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Muthiah, S. (6 May 2012). "Integrating transport". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "The South's first station". The Hindu. Chennai. 26 February 2003. Archived from the original on 2 July 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Chapter 1 – Evolution of Indian Railways-Historical Background". Ministry of Railways website. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009.

- ^ Report on the Administration of the Madras Presidency During the Year 1875–76. Government Press. 1877. p. 260.

- ^ "IR Electrification Chronology up to 31 March 2004". History of Electrification. IRFCA.org. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Sriram, V. (10 October 2008). "To market, to market..." India Today. Chennai. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Narayanan, Arjun; Khaja, Fathima (23 August 2013). "On the TRACK". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Vydhianathan, S. (7 March 2005). "Chennai Central gets back its brick-red colour". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Chennai Central stn on alert after intel warns of 'attack'". The Times of India. Chennai. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Brief History of the Division" (PDF). Chennai Division. Indian Railways-Southern Railways. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ Venkataraman, G. "History of Historical Building and Monuments in and around Chennai" (PDF). Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Madras – The Architectural Heritage, ISBN 81-901640-0-7, p53

- ^ "Roorkee experts to help save heritage". The Hindu. 9 June 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ a b Sujatha, R. (7 August 2012). "Man perches atop clock tower of Chennai Central". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Srikanth, R. (11 June 2017). "Central Station Makeover Hits a Bump". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ a b Venkat, Vidya (22 May 2008). "Cleaning machines offer little help to sanitary workers at Central Station". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b Srikanth, R. (24 November 2009). "Four platforms to be extended at Chennai Central Station". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "A Case Study on Replacement of Screw Piles by Well Foundation Under Running Traffic" (PDF). Project Report. Indian Railway Institute of Civil Engineering. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Southern Railway—Harbinger for Progressive Changes" (PDF). GM's Article for the Annual Issue of the "Indian Railways". Southern Railway. 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Narayanan, Vivek; Petlee, Peter (27 May 2012). "SOS...Chennai Central needs doctors". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Return of display boards brings cheer to rail passengers". The Hindu. Chennai. 6 June 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ a b Vydhianathan, S. (26 October 2004). "Second terminal at Chennai Central proposed". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 1 December 2004. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "No more fish stench at Central railway station". The Indian Express. Chennai. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Lakshmi, K. (26 June 2012). "It's a long transit for parcels at Central". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Sundaram, Ram M (29 December 2015). "When Mr Bean Comes Calling at the Central Railway Station". The New Indian Express. Chennai. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Sarkar, Arita (30 June 2012). "Lack of display system on platforms at Central leaves passengers clueless". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Ananthakrishnan, G. (5 November 2012). "A waste of Central space". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Sreevatsan, Ajai (7 May 2011). "Erratic PNR machines irk passengers". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Velupillai, Krishna (3 January 2008). "New timing boards at Chennai central station". The Hindu. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "New display facility at Central". The Hindu. 30 November 2009. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Sekar, Sunitha (9 February 2013). "Stations lacking". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ Prabhakar, Siddharth (20 September 2018). "Chennai Central railway station gets 5,000 litre drinking water plant". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Vidya, Venkat (25 May 2008). "Treading rough and rugged tracks, loaded with woes". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Platform car at Chennai Central for elderly, disabled". The Times of India. Chennai. 8 January 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ Narayanan, Vivek (27 September 2014). "Central station is first in country to get free Wi-Fi". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Bustling Central lacks emergency care: PIL". The Times of India. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Subramani, A (17 December 2012). "24-hour emergency medicare facility soon at Chennai central railway station". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Set up health centre at Central Station in three months: Court". The Hindu. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Ayyappan, V. (16 April 2013). "Chennai Central gets 24/7 emergency medical centre". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Yogesh Kabirdoss (22 October 2012). "Parking fee hike at Central draws commuter's ire". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Kannal Achuthan (8 March 2008). "'Premium' parking lot for cars at Chennai Central to be opened". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Premium parking lot reopens at Central railway station". The Hindu. 14 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Liffy (30 April 2011). "Relief for car parking lot users at Central station". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ a b Karthikeyan, K. (20 July 2012). "Maintenance not on right track". The Asian Age. Chennai. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Cleanliness drive in railway stations". The Hindu. Chennai. 8 July 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Kumar, S. Vijay (25 October 2012). "Southern Railway goes in for bio-toilets in trains". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Varma, M. Dinesh (7 December 2012). "New agency undertakes cleaning of Egmore station". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ "About Us". Southern Railway. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ a b Ayyappan, V. (9 July 2012). "Railway staff battle muck, indifference". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Clean-up starts at Basin Bridge train care centre". The Times of India. Chennai. 18 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Ayyappan, V. (29 October 2012). "Passengers panic as pests overrun dirty train bogies". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Train care centre in Chennai needs thorough overhaul". The Times of India. Chennai. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Saqaf, Syed Muthahar; R. Rajaram (23 August 2010). "Electric locomotive trip shed at Tiruchi junction". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ "Locomotive Sheds". Sheds and Workshops. Irfca.org. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Goods Sheds". Freight Sheds and Marshalling Yards. Irfca.org. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Madhavan, D. (27 October 2015). "Chennai Central Station gets facelift after 5 years". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ "Tricolour flies at a 100-ft high at Central". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. 16 February 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ "Chennai suburban train time table". Indian Railways. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Chennai Central to be biggest metro station". Magic Bricks.com. Chennai: MagicBricks.com. 30 August 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Metro rail seals fate of shops near Central". The Hindu. Chennai. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Sridhar, Asha (25 April 2012). "Mini-bus facility at airport fails to take off". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ M, Lavanya (29 May 2012). "Auto and taxi drivers badly hit". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Autos in short supply at Chennai Central railway station". The Times of India. Chennai. 3 January 2012. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ a b Hemalatha, Karthikeyan (4 June 2011). "Central: Where jaywalkers, callous bus drivers face off". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "Hawkers force public to choose road over subways". Deccan Chronicle. Chennai. 6 August 2012. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Vydhianathan, S. (15 April 2003). "Central-Egmore link project stone-laying tomorrow". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Nitish lays foundation for Central-Egmore rail link". Business Line. Chennai. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Vydhianathan, S. (21 October 2002). "Central-Egmore rail link may fail to get official nod". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Metro – Urban – Suburban Systems". Irfca.org. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Balaji, J. (2 September 2008). "Central-Egmore link: Railways presses for NOC". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 3 September 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Lakshmi, K. (22 September 2012). "Out with the dirt: canal clean-up after 14 years". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Platform car at Chennai Central for elderly, disabled". Business Line. Chennai. 14 August 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ Vijaya Kumar, S.; S. Vydhianathan (30 April 2009). "Hijack leads to train collision, 4 die". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Bizarre Rail Accident in Chennai Kills 4". Outlook India. Chennai: OutlookIndia.com. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "7 killed in train accident in Tamil Nadu". India Today. Chennai: IndiaToday.in. 29 April 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Blasts at Chennai Central railway station kill 1, cops detain suspect". First Post. May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Mohan, Gopu (28 October 2014). "1 killed and 14 injured after twin blasts hit train at Chennai station". The Indian Express. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ "Passengers stranded as 16 trains from, via Chennai cancelled due to COVID-19". The New Indian Express. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "After six months, train services from Chennai to Kerala and Karnataka to resume on Sunday". The New Indian Express. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "RPF bomb squad for Chennai Central". The Hindu. Chennai. 3 May 2002. Archived from the original on 30 December 2004. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "S Railway sanctions Rs 15-cr scheme". The Times of India. Chennai. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Peter, Petlee (25 May 2009). "Rail passengers find it hard to locate police station". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "At Central, railway police feel the heat!". The Hindu. 21 May 2005. Archived from the original on 23 May 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ "Central station CCTV nets its first suspect". The Hindu. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ a b Varma, M. Dinesh (7 November 2012). "Chennai Central, Egmore to come under high-tech security blanket". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Railway police launches two helplines". The Hindu. Chennai. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Chennai Central gets 360-degree surveillance". Deccan Chronicle. Chennai. 16 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ "Hi-tech security system launched at Central, Egmore rail stations". The Hindu. Chennai. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ UNI (14 June 2007). "Chennai Central station to be upgraded". One India News. Chennai: OneIndia.in. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ a b Kumar, S. Vijaya (10 August 2009). "Chennai Central station to get world-class facilities in 5 years". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Giri, Greeshma Gopal (19 November 2009). "Rs 100-cr facelift for Chennai Central Station". The New Indian Express. Chennai: Express Publications. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Adimathra, George (30 March 2011). "Chennai Central plan diverted to slow line". Deccan Chronicle. Chennai. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "First skywalk to link Chennai Central with GH". The Hindu. Chennai. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Ayyappan, V. (14 February 2013). "Central, Egmore stns to get washable tracks". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ "Chennai to get Rs 400 crore 'Central Square'". The Times of India. 16 September 2015.

- ^ Sekar, Sunitha; Aloysius Xavier Lopez and Deepa H. Ramakrishnan (14 September 2017). "CMRL plans a towering monolith near Central". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Sekar, Sunitha (14 September 2017). "One square to link them all". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Chennai Central railway station to be renamed after MGR: Modi announces". TheNewsMinute. 6 March 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Central station sans Chennai may cause confusion among commuters". The New Indian Express. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Nanisetti, Serish (14 April 2019). "Chennai Central loses the honour of having longest railway station name by 1 letter". The Hindu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Vardhan, Harsh (October 2006). "Indian Steam in Cinema". IRFCA.org. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ "Award Winning Poems – AIPC 1988". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "India Uncut – Madras Central by Nambisan". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ Mariappan, Julie (13 July 2010). "Ripon Buildings to get stamp of recognition". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

External links

[edit] Media related to Chennai Central railway station at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chennai Central railway station at Wikimedia Commons