Psilocybe hoogshagenii

| Psilocybe hoogshagenii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Psilocybe hoogshagenii in Mocoa, Putumayo Dept, Colombia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Hymenogastraceae |

| Genus: | Psilocybe |

| Species: | P. hoogshagenii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Psilocybe hoogshagenii Heim (1958)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Psilocybe caerulipes var. gastonii Singer (1958) | |

| Psilocybe hoogshagenii | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is conical or convex | |

| Hymenium is adnate or adnexed | |

| Stipe is bare | |

| Spore print is purple-brown | |

| Ecology is saprotrophic | |

| Edibility is psychoactive | |

Psilocybe hoogshagenii is a species of psilocybin mushroom in the family Hymenogastraceae. The mushroom has a brownish conical or bell-shaped cap up to 3 cm (1.2 in) wide that has an extended papilla up to 4 mm long. The stem is slender (up to 3 mm thick) and 5 to 9 cm (2.0 to 3.5 in) long. The variety P. hoogshagenii var. convexa lacks the long papilla.

The species is found in Mexico, where it grows singly or in small groups in clayey soils in subtropical coffee plantations, and from Colombia and Brazil in South America. The mushroom contains the psychedelic compounds psilocybin and psilocin, and all parts will stain blue or bluish black when handled or injured. P. hoogshagenii is used for divinatory purposes by some indigenous groups in Mexico.

Taxonomy

[edit]The species was first described scientifically by French mycologist Roger Heim in 1958.[2] It was one of several species described and illustrated in the popular American weekly magazine Life ("Seeking the Magic Mushroom"), in which R. Gordon Wasson recounted the psychedelic visions that he experienced during the divinatory rituals of the Mixtec people, thereby introducing psilocybin mushrooms to Western popular culture;[3] it was however, mislabeled as Psilocybe zaptecorum.[4] Similarly, Psilocybe specialist Gastón Guzmán suggests that P. zapotecorum, as described by Rolf Singer in 1958,[5] is misidentified as it agrees well with the type of P. hoogshagenii.[1] The species Psilocybe caerulipes var. gastonii, described by Singer in 1958,[5] is a synonym of P. hoogshagenii.[1]

The species is named in honor of American anthropologist Searle Hoogshagen,[6] who helped Heim and Wasson in their search for entheogenic mushrooms in Mexico.[1] The mushroom is known locally by several common names. In Spanish, it is called los niños or los Chamaquitos ("the little boys"), in Mazatec as pajaritos de monte ("little birds of the woods"), in Nahuatl as cihuatsinsintle or teotlaquilnanácatl ("divine mushroom that describes or paints"), and in Mixe as Atka:t ("judge") or na.shwi.ñ mush ("mushrooms of the earth").[7]

The variety P. hoogshagenii var. convexa was described by Guzmán in 1983 to account for mushrooms without an acute papilla that were otherwise roughly the same as the type variety. Psilocybe semperviva, described by Heim and Roger Cailleux in 1958,[8] was later determined by Guzmán to be synonymous with P. hoogshagenii var. convexa.[9] The varietal epithet convexa refers to the convex shape of the cap.[1]

Description

[edit]The cap ranges in shape from conical to bell-shaped to convex, reaching diameters of 0.7–3 in (18–76 mm), although a range of 1–2.5 cm (0.4–1.0 in) is most usual. It has a long, sharp papilla that is up to 4 mm (0.16 in). The cap surface is smooth, somewhat sticky when wet, and often has ridges extending halfway to the center of the cap. Its color is reddish brown to orangish brown to yellowish, and it is hygrophanous, fading when dry to a straw or fulvous color. The brownish gills have an adnate to adnexed attachment to the stem; mature gills become purplish black because of the spores. The hollow stem measures 50 to 90 mm (2.0 to 3.5 in) long by 1–3 mm thick. It is roughly equal in width throughout its length or slightly thicker at the base, and sometimes twisted. A thin rudimentary cortina-like partial veil covers the gills of immature fruit bodies, but it is fragile and disappears soon after the cap expands. The flesh in the cap is whitish, but more yellow in the stem. Both the odor and taste of the mushroom are farinaceous (similar to freshly ground flour). As is characteristic of psilocybin mushrooms, all parts of the fruit body bruise blue when handled or injured. P. hoogshagenii var. convexa lacks an acute papilla, although it occasionally has a small, rounded papilla. Its cap ranges in width from 0.5–1.5 cm (0.20–0.59 in), and it is convex to roughly bell-shaped. All other macroscopic and microscopic features are identical to the type variety.[1]

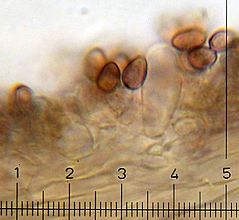

The spore print is dark purplish brown. Spores are rhomboid or nearly so in face view, and more or less ellipsoid when viewed from the side. They are thick-walled, with dimensions of 6.5–4–5.6 μm, and feature a broad germ pore. The basidia (spore-bearing cells) are usually four-spored, hyaline (translucent), roughly cylindrical or with a central constriction, and measure 12–22 by 5.5–9 μm. Pleurocystidia (cystidia on the gill face) are relatively abundant; they are ventricose (swollen), club-shaped or irregularly shaped, measuring 16–36 by 8–12 μm. The cheilocystidia (cystidia on the gill edge) are also abundant. They are 19–35 by 4.4–6.6 μm, lageniform (flask-shaped), narrowing into a long neck with a width of 1–3 μm, and either acute or somewhat capitate (ending in a roughly globular tip). Clamp connections are present in the hyphae.[1]

Habitat and distribution

[edit]Fruit bodies of Psilocybe hoogshagenii grow solitarily or in small groups in humus or in muddy clay soils in subtropical coffee plantations. According to the natives of the San Agustin Loxicha region of Mexico, the fungus tends to fruit simultaneously in large flushes.[1] In Mexico, fruiting occurs in June and July, whereas in Argentina, fruiting is in February. The mushroom has been reported from Mexico in the states of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Chiapas, where it grows at elevations of 1,000 to 1,800 m (3,300 to 5,900 ft).[10] In South America, the species is known from Brazil and Colombia.[11] P. hoogshagenii var. convexa has been found in grasslands in Hidalgo, and Oacaxa, but is most common in Puebla. It fruits from June to August.[1]

Uses

[edit]Psilocybe hoogshagenii mushrooms are used for entheogenic, or spiritual, purposes by some Chinantec-speaking curanderos of the Ixtlán District in Oacaxa.[12] The mushrooms are primarily used to diagnose and prognose illness, and, to a lesser extent, to divine the location of objects or animals that have been lost or stolen.[13] Guzmán also indicates contemporary ceremonial usage by Mixe and Zapotec people.[14] Paul Stamets, in his Psilocybe Mushrooms of the World, rates the psychoactive potency of the mushroom as "moderately active", and reports psilocybin levels of 0.6% (milligrams per gram of dried mushroom), and psilocin of 0.1%. In comparison, Stamets indicates that the commonly cultivated species P. cubensis contains 0.63% and 0.60% (psilocybin and psilocin), while the widespread P. semilanceata has 0.98% and 0.02%.[15] Chemical analysis of P. hoogshagenii specimens from Brazil yielded up to 0.3% psilocybin and 0.3% psilocin.[16] This species is used by mushroom growers for the myceliated grain technique, because it produces viable amounts of psilocybin in the mycelium phase.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Guzmán G. (1983). The Genus Psilocybe: A Systematic Revision of the Known Species Including the History, Distribution, and Chemistry of the Hallucinogenic Species. Beihefte Zur Nova Hedwigia. Heft 74. Vaduz, Liechtenstein: J. Cramer. pp. 129–33. ISBN 978-3-7682-5474-8.

- ^ "Psilocybe hoogshagenii R. Heim 1958". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2012-06-25.

- ^ Wasson RG. (13 May 1957). "Seeking the magic mushroom". Life. Time Inc. pp. 101–20. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ Beug M. (2011). "The genus Psilocybe in North America" (PDF). Fungi Magazine. 4 (3): 6–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-31.

- ^ a b Singer R. (1958) [1959]. Fungi Mexicani, series secunda, Agaricales (PDF). Beihefte zur Sydowia. Vol. 12. pp. 221–43.

- ^ Hoogshagen S. (1959). "Notes on the sacred narcotic mushroom from Coatlán, Oaxaca, Mexico". Oklahoma Anthropological Society Bulletin. 7: 71–4.

- ^ Allen JW. (1997). Teonanácatl: Ancient and Contemporary Shamanic Mushroom Names of Mesoamerica and Other Regions of the World. Ethnomycological Journals. Vol. 3. Seattle, Washington: Psilly Publications. p. 6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Heim R, Cailleux R (1958). "Latin diagnosis Psilocybe semperviva Heim et Cailleux, speciei mutantis hallucinogenae mexicanae per culturam obtentae". Revue Mycologique (in Latin). 23: 352–3.

- ^ Guzmán G. (1978). "Further investigations of the Mexican hallucinogenic mushrooms with descriptions of new taxa and critical observations on additional taxa". Nova Hedwigia. 29: 625–44.

- ^ Stamets P. (1996). Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World: An Identification Guide. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. pp. 118–9. ISBN 0-89815-839-7.

- ^ Guzmán G, Allen JW, Gartz J (2000). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion" (PDF). Annali del Museo Civico di Rovereto: Sezione Archeologia, Storia, Scienze Naturali. 14: 189–280.

- ^ Ramírez-Cruz V, Guzmán G, Ramírez-Guillén F (2006). "Las especies del género Psilocybe conocidas del Estado de Oaxaca, su distribución y relaciones étnicas" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Micología (in Spanish). 23: 27–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ^ Rubel AJ, Gettelfinger-Krejci J (1976). "The use of hallucinogenic mushrooms for diagnostic purposes among some highland Chinantecs". Economic Botany. 30 (3): 235–48. Bibcode:1976EcBot..30..235R. doi:10.1007/bf02909732. JSTOR 4253740. S2CID 9249098.

- ^ Guzmán G. (2008). "Hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico: an overview". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 404–12. Bibcode:2008EcBot..62..404G. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9033-8. S2CID 22085876.

- ^ Stamets (1996), p. 39.

- ^ Stijve TC, de Meijer AA (1993). "Macromycetes from the state of Paraná, Brazil. 4. The psychoactive species". Arquivos de Biologia e Tecnologia. 36 (2): 313–29.

- ^ Smith, Patrick (2020-04-14). "A New Way to Grow Magic Mushrooms (Without the Shrooms!)". EntheoNation. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

External links

[edit]