Pseudoexfoliation syndrome

| Pseudoexfoliation syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pseudoexfoliation of the lens, exfoliation syndrome |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Pseudoexfoliation syndrome, often abbreviated as PEX[1] and sometimes as PES or PXS, is an aging-related systemic disease manifesting itself primarily in the eyes which is characterized by the accumulation of microscopic granular amyloid-like protein fibers.[2] Its cause is unknown, although there is speculation that there may be a genetic basis. It is more prevalent in women than men, and in persons past the age of seventy. Its prevalence in different human populations varies; for example, it is prevalent in Scandinavia.[2] The buildup of protein clumps can block normal drainage of the eye fluid called the aqueous humor and can cause, in turn, a buildup of pressure leading to glaucoma and loss of vision[3] (pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, exfoliation glaucoma). As worldwide populations become older because of shifts in demography, PEX may become a matter of greater concern.[4]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Patients may have no specific symptoms. In some cases, patients may complain of lessened visual acuity or changes in their perceived visual field, and such changes may be secondary to or different from symptoms normally associated with cataracts or glaucoma.[4]

PEX is characterized by tiny microscopic white[5] or grey[6] granular flakes[4] which are clumps of proteins within the eye which look somewhat like dandruff when seen through a microscope and which are released by cells.[7] The abnormal[8] flakes, sometimes compared to amyloid-like material,[2][4] are visible during an examination of the lens of an eye by an ophthalmologist or optometrist, which is the usual diagnosis.[7] The white fluffy material is seen in many tissues both ocular and extraocular,[8] such as in the anterior chamber structures,[4][5] trabecular meshwork, central disc, zonular fibres, anterior hyaloid membrane, pupillary and anterior iris, trabecula, and occasionally the cornea.[9][10] The flakes are widespread.[8] One report suggested that the granular flakes were from abnormalities of the basement membrane in epithelial cells, and that they were distributed widely throughout the body and not just within structures of the eye. There is some research suggesting that the material may be produced in the iris pigment epithelium, ciliary epithelium, or the peripheral anterior lens epithelium.[4] A similar report suggests that the proteins come from the lens, iris, and other parts of the eye.[3] A report in 2010 found indications of an abnormal ocular surface in PEX patients, discovered by an eye staining method known as rose bengal.[11]

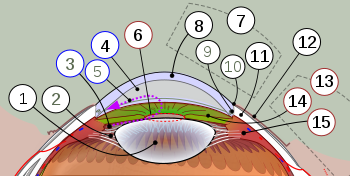

1. Lens, 2. Zonule of Zinn or ciliary zonule, 3. Posterior chamber and 4. Anterior chamber with 5. Aqueous humour flow; 6. Pupil, 7. Corneosclera with 8. Cornea, 9. Trabecular meshwork and Schlemm's canal. 10. Corneal limbus and 11. Sclera; 12. Conjunctiva, 13. Uvea with 14. Iris, 15. Ciliary body.

PEX can become problematic when the flakes become enmeshed in a "spongy area" known as the trabecular meshwork and block its normal functioning,[2] and may interact with degenerative changes in the Schlemm's canal and the juxtacanalicular area.[4] The blockage leads to greater-than-normal elevated intraocular pressure[2] which, in turn, can damage the optic nerve.[7] The eye produces a clear fluid called the aqueous humor which subsequently drains such that there is a constant level of safe pressure within the eye, but glaucoma can result if this normal outflow of fluid is blocked. Glaucoma is an umbrella term indicating ailments which damage the neural cable from the eye to the brain called the optic nerve, and which can lead to a loss of vision. In most cases of glaucoma, typically called primary open-angle glaucoma, the outflow does not happen normally but doctors can not see what is causing the blockage; with PEX, however, the flakes are believed to be a cause of the blockage.[7] PEX flakes by themselves do not directly cause glaucoma, but can cause glaucoma indirectly by blocking the outflow of aqueous humor, which leads to higher intraocular pressure, and this can cause glaucoma.[4] PEX has been known to cause a weakening of structures within the eye which help hold the eye's lens in place, called lens zonules.[2]

Causes

[edit]The cause of pseudoexfoliation glaucoma is generally unknown.[2][4][7]

PEX is generally believed to be a systemic disorder,[2][4][6] possibly of the basement membrane of the eye.[2] Researchers have noticed deposits of PEX material in various parts of the body, including in the skin, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and elsewhere.[6] Nevertheless, what is puzzling is that PEX tends to happen in only one eye first, which scientists call unilaterality,[2] and in some cases, gradually affects the other eye, which is termed bilaterality.[4][9] According to this reasoning, if PEX were a systemic disorder, then both eyes should be affected at the same time, but they are not.[9] There are contrasting reports about the extent and speed with which PEX moves from one eye to both eyes. According to one report, PEX develops in the second eye in 40% of cases. A contrasting report was that PEX can be found in both eyes in almost all situations if an electron microscope is used to examine the second eye, or if a biopsy of the conjunctiva was done, but that the extent of PEX is the second eye was much less than the first one.[4] A different report suggested that two thirds of PEX patients had flakes in only one eye.[9][12] In one long-term study, patients with PEX in only one eye were studied, and it was found that over time, 13% progressed to having both eyes affected by PEX.[9] Scientists believe that elevated levels of plasma homocysteine are a risk factor for cardiovascular disease,[4] and two studies have found higher levels of plasma homocysteine in PEX patients,[13] or elevated homocysteine concentrations in tear fluids produced by the eye.[14]

There is speculation that PEX may be caused by oxidative damage and the presence of free radicals, although the exact nature of how this might happen is still under study.[4] Studies of PEX patients have found a decrease in the concentrations of ascorbic acid,[15] increase in concentrations of malondialdehyde,[16] and an increase in concentrations of 8-iso-prostaglandinF2a.[17]

There is speculation that genetics may play a role in PEX.[4][6] A predisposition to develop PEX later in life may be an inherited characteristic, according to one account.[4] One report suggested the genetic component was "strong".[1] One study performed in Iceland and Sweden has associated PEX with polymorphisms in gene LOXL1.[5] A report suggested that a specific gene named LOXL1 which was a member of the family of enzymes which play a role in the linking of collagen and elastin inside cells. LOXL1 was responsible for "all the heritability" of PEX, according to one source. Two distinct mutations in which a single nucleotide was changed, or called a single nucleotide polymorphism or SNP, was discovered in Scandinavian populations and confirmed in other populations, and may be involved with the onset of PEX.[6]

The gene is called LOXL1 ... Because pseudoexfoliation syndrome is associated with abnormalities of the extracellular matrix and the basement membrane, this gene could reasonably play a role in the pathophysiology of the condition.

— Dr. Allingham[6]

Researchers are investigating whether factors such as exposure to ultraviolet light, living in northern latitudes, or altitude influence the onset of PEX. One report suggested that climate was not a factor related to PEX.[4] Another report suggested a possible link to sunlight as well as a possible autoimmune response, or possibly a virus.[1]

Diagnosis

[edit]PEX is usually diagnosed by an eye doctor who examines the eye using a microscope. The method is termed slit lamp examination and it is done with an "85% sensitivity rate and a 100% specificity rate."[4] Since the symptom of increased pressure within the eye is generally painless until the condition becomes rather advanced, it is possible for people affected by glaucoma to be in danger yet not be aware of it. As a result, it is recommended that persons have regular eye examinations to have their levels of intraocular pressure measured, so that treatments can be prescribed before there is any serious damage to the optic nerve and subsequent loss of vision.[7]

Treatment

[edit]

While PEX itself is untreatable as of 2011[update], it is possible for doctors to minimize the damage to vision and to the optic nerves by the same medical techniques used to prevent glaucoma.

- Eyedrops. This is usually the first treatment method. Eyedrops can help reduce intraocular pressure within the eye. The medications within the eyedrops can include beta blockers (such as levobunolol or timolol) which slow the production of the aqueous humor. And other medications can increase its outflow, such as prostaglandin analogues (e.g. latanoprost). And these medicines can be used in various combinations.[7] In most cases of glaucoma, eyedrops alone will suffice to solve the problem.

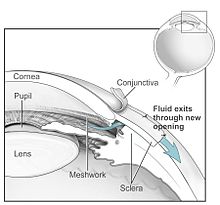

- Laser surgery. A further treatment is a type of laser therapy known as trabeculoplasty in which a high-energy laser beam is pointed at the trabecular meshwork to cause it to "remodel and open" and improve the outflows of the aqueous humor. These can be done as an outpatient procedure and take less than twenty minutes. One report suggests this procedure is usually effective.[2]

- Eye surgery. Surgery is the treatment method of last resort if the other methods have not worked. It is usually effective at preventing glaucoma.[2] Eye surgery on PEX patients can be subject to medical complications if the fibers which hold the lens have become weakened because of a buildup from the flakes; if the lens-holding fibers have weakened, then the lens may become loose, and complications from eye surgery may result.[7] In such cases, it is recommended that surgeons act quickly to repair the phacodonesis before the lenses have dropped.[18] A surgeon cuts an opening in the white portion of the eye known as the sclera, and removes a tiny area of the trabecular meshwork which enables the aqueous humor to discharge.[7] This lowers the internal pressure within the eye and lessens the chance of future damage to the optic nerve.[7] Cases with pseudophacodonesis and dislocated IOL have been increasing in number, according to one report.[18] In cataract surgery, complications resulting from PEX include capsular rupture and vitreous loss.[2]

- Drug therapy. There are speculations that if genetics plays a role in PEX, and if the specific genes involved can be identified, that possibly drugs can be developed to counteract these mutations or their effects.[6] But such drugs have not been developed as of 2011[update].

Patients should continue to have regular eye examinations so that physicians can monitor pressure levels and check whether medicines are working.

Epidemiology

[edit]Scientists are studying different populations and relationships to try to learn more about the disease. They have found associations with different groups but it is not yet clear what the underlying factors are and how they affect different peoples around the world.

- Glaucoma patients. While PEX and glaucoma are believed to be related, there are cases of persons with PEX without glaucoma, and persons with glaucoma without PEX.[4] Generally, a person with PEX is considered as having a risk of developing glaucoma, and vice versa. One study suggested that the PEX was present in 12% of glaucoma patients.[4][19] Another found that PEX was present in 6% of an "open-angle glaucoma" group.[20] Pseudoexfoliation syndrome is considered to be the most common of identifiable causes of glaucoma.[5] If PEX is diagnosed without glaucoma, there is a high risk of a patient subsequently developing glaucoma.[3]

- Country and region. Prevalence of PEX varies by geography. In Europe, differing levels of PEX were found; 5% in England, 6% in Norway, 4% in Germany, 1% in Greece, and 6% in France.[4] One contrary report suggested that levels of PEX were higher among Greek people.[21] One study of a county in Minnesota found that the prevalence of PEX was 25.9 cases per 100,000 people.[22] It is reportedly high in northern European countries such as Norway, Sweden and Finland,[2] as well as among the Sami people of northern Europe, and high among Arabic populations,[23][24] but relatively rare among African Americans and Eskimos. In southern Africa, prevalence was found to be 19% of patients in a glaucoma clinic attending to persons of the Bantu tribes.[25]

- Race. It varies considerably according to race.[4]

- Gender. It affects women more than men. One report was that women were three times more likely than men to develop PEX.[4][26]

- Age. Older persons are more likely to develop PEX.[2][4] And persons younger than 50 are highly unlikely to have PEX. A study in Norway found that the prevalence of PEX of persons aged 50–59 was 0.4% while it was 7.9% for persons aged 80–89 years.[27] If a person is going to develop PEX, the average age in which this will happen is between 69 and 75 years, according to the Norwegian study.[4] A second corroborating report suggested that it happens primarily to people 70 and older.[2] While older people are more likely to develop PEX, it is not seen as a "normal" part of aging.[4]

- Other diseases. Sometimes PEX is associated with the development of medical problems other than merely glaucoma. There are conflicting reports about whether PEX is associated with problems of the heart or brain; one study suggested no correlations[28] while other studies found statistical links with Alzheimer's disease, senile dementia, cerebral atrophy, chronic cerebral ischemia, stroke, transient ischemic attacks, heart disease, and hearing loss.[4]

History

[edit]Pseudoexfoliation syndrome (PEX) was first described by an ophthalmologist from Finland named John G. Lindberg in 1917.[4][5] He built his own slit lamp to study the condition and reported "grey flakes on the lens capsule", as well as glaucoma in 50% of the eyes, and an "increasing prevalence of the condition with age."[6] Several decades later, an ocular pathologist named Georgiana Dvorak-Theobald suggested the term pseudoexfoliation to distinguish it from a similar ailment which sometimes affected glassblowers called true exfoliation syndrome that was described by Anton Elschnig in 1922.[29] The latter ailment is caused by heat or "infrared-related changes in the anterior lens capsule" and is characterized by "lamellar delamination of the lens capsule."[4] Sometimes the two terms "pseudoexfoliation" and "true exfoliation" are used interchangeably[6] but the more precise usage is to treat each case separately.

Research

[edit]Scientists and doctors are actively exploring how PEX happens, its causes, and how it might be prevented or mitigated. Research activity to explore what causes glaucoma has been characterized as "intense".[7] There has been research into the genetic basis of PEX. One researcher speculated about a possible "two-hit hypothesis" in which a single mutation in the LOXL1 gene puts people at risk for PEX, but that a second still-to-be-found mutation has some effect on the proteins, possibly affecting bonds between chemicals, such that the proteins are more likely to clump together and disrupt the outflow of aqueous humor.[6][30]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Glaucoma In-Depth Report". The New York Times. July 9, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome ... The substance is composed of proteins produced by the lens, iris, and other parts of the eye. People can have this condition and not develop glaucoma, but they are at high risk.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Yichieh Shiuey, MD (March 26, 1997). "Glaucoma Quiz 1". Digital Journal of Ophthalmology. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

... In Scandinavia, this condition represents greater than 50% of all cases of open angle glaucoma.

- ^ a b c "Glaucoma". The New York Times. August 19, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

... Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome (also known as exfoliation syndrome) is the most common identifiable condition associated with glaucoma. The substance is composed of proteins produced by the lens, iris, and other parts of the eye.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Pons, Mauricio E (July 16, 2021). "Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome (Pseudoexfoliation Glaucoma): Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Medscape Reference. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Damji, Karim F. (October 2007). "Progress in understanding pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation-associated glaucoma". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 42 (5): 657–658. doi:10.3129/I07-158. PMID 17891191.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tony Realini, M.D. "A new gene for pseudoexfoliation". EyeWorld. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

A new gene defect has been found that accounts for essentially all the heritability of pseudoexfoliation syndrome.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Arthur J. Sit, MD (April 23, 2006). "Many types of glaucoma, one kind of damage to optic nerve". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

Glaucoma is a broad term for a number of different conditions that damage the optic nerve, the 'cable' that carries visual information from the eye to the brain, thereby causing changes in vision.

- ^ a b c N Demir; T Ulus; O E Yucel; E T Kumral; E Singar; H I Tanboga (June 24, 2011). "Assessment of myocardial ischaemia using tissue Doppler imaging in pseudoexfoliation syndrome". Eye. 25 (9): 1177–1180. doi:10.1038/eye.2011.145. PMC 3178234. PMID 21701523.

- ^ a b c d e M Citirik; G Acaroglu; C Batman; L Yildiran; O Zilelioglu (2007). "A possible link between the pseudoexfoliation syndrome and coronary artery disease". Eye. 21 (1): 11–15. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702177. PMID 16557288.

- ^ Mizuno, K.; Muroi, S. (1979). "Cycloscopy of Pseudoexfoliation". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 87 (4): 513–518. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(79)90240-X. PMID 443315.

- ^ "Data from E. Viso and colleagues advance knowledge in exfoliation syndrome epidemiology". Biotech Week. NewsRX LLC: 1802. April 28, 2010. ISSN 1535-2757. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Henry, J. Charles; Krupin, Theodore; Schmitt, Michael; Lauffer, Jason; Miller, Eva; Ewing, Madeleine Q.; Scheie, Harold G. (1987). "Long-term Follow-up of Pseudoexfoliation and the Development of Elevated Intraocular Pressure". Ophthalmology. 94 (5): 545–552. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(87)33413-X. PMID 3601370.

- ^ Vessani, Roberto M; Ritch, Robert; Liebmann, Jeffrey M; Jofe, Mark (2003). "Plasma homocysteine is elevated in patients with exfoliation syndrome". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 136 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00077-1. PMID 12834668.

- ^ Roedl, Johannes B.; Bleich, Stefan; Reulbach, Udo; Rejdak, Robert; Kornhuber, Johannes; Kruse, Friedrich E.; Schl??tzer-Schrehardt, Ursula; J??nemann, Anselm G. (2007). "Homocysteine in Tear Fluid of Patients With Pseudoexfoliation Glaucoma". Journal of Glaucoma. 16 (2): 234–239. doi:10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802d6942. ISSN 1057-0829. PMID 17473737.

- ^ Koliakos, George G; Konstas, Anastasios G.P; Schlötzer-Schrehardt, Ursula; Bufidis, Theodoros; Georgiadis, Nikolaos; Ringvold, Amund (2002). "Ascorbic acid concentration is reduced in the aqueous humor of patients with exfoliation syndrome". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 134 (6): 879–883. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01797-X. PMID 12470757.

- ^ Yılmaz, Ayça; Adıgüzel, Ufuk; Tamer, Lülüfer; Yıldırım, Özlem; Öz, Özay; Vatansever, Halil; Ercan, Bahadır; Değirmenci, Ula¸s; Atik, Uğur (2005). "Serum oxidant/antioxidant balance in exfoliation syndrome: Laboratory Science". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 33 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.00944.x. ISSN 1442-6404. PMID 15670081.

- ^ Koliakos, G G (March 1, 2003). "8-Isoprostaglandin F2a and ascorbic acid concentration in the aqueous humour of patients with exfoliation syndrome". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 87 (3): 353–356. doi:10.1136/bjo.87.3.353. PMC 1771526. PMID 12598453.

- ^ a b Rich Daly. "Pseudoexfoliation syndrome's surgical challenge". EyeWorld. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

... Dr. Crandall urges surgeons to probe for such changes early because it is surgically much easier to repair the phacodonesis before the lenses have dropped.

- ^ Roth, Michael; Epstein, David L. (1980). "Exfoliation Syndrome". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 89 (4): 477–481. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(80)90054-9. PMID 7369310.

- ^ Cashwell LF Jr; Shields MB (1988). "Exfoliation syndrome in the southeastern United States. I. Prevalence in open-angle glaucoma and non-glaucoma populations". Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 184: 99–102. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1988.tb02637.x. PMID 2853929. S2CID 11580299.

- ^ "Greek population has higher prevalence of pseudoexfoliation". BioPortfolio. April 15, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

Pseudoexfoliation was found to be more prevalent in Greece than in other white populations,

- ^ Karger, Randy A.; Jeng, Samuel M.; Johnson, Douglas H.; Hodge, David O.; Good, Margaret S. (2003). "Estimated Incidence of Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome and Pseudoexfoliation Glaucoma in Olmsted County, Minnesota". Journal of Glaucoma. 12 (3): 193–197. doi:10.1097/00061198-200306000-00002. ISSN 1057-0829. PMID 12782834.

- ^ Summanen, Paula; Tönjum, Asbjörn M. (1988). "Exfoliation Syndrome Among Saudis". Acta Ophthalmologica. 66 (S184): 107–111. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1988.tb02639.x. ISSN 1755-375X. PMID 2853905.

- ^ Bialasiewicz, A. A.; Wali, U.; Shenoy, R.; Al-Saeidi, R. (2005). "Patienten mit sekundärem Offenwinkelglaukom bei Pseudoexfoliations- (PEX-)Syndrom in einer Bevölkerung mit hoher PEX-Prävalenz: Klinische Befunde, morphologische und operative Besonderheiten". Der Ophthalmologe (in German). 102 (11): 1064–1068. doi:10.1007/s00347-005-1226-2. ISSN 0941-293X. PMID 15871021.

- ^ Bartholomew, R S (January 1, 1973). "Pseudocapsular exfoliation in the Bantu of South Africa. II. Occurrence and prevalence". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 57 (1): 41–45. doi:10.1136/bjo.57.1.41. ISSN 0007-1161. PMC 1214820. PMID 4705496.

- ^ Kozart, David M.; Yanoff, Myron (1982). "Intraocular Pressure Status in 100 Consecutive Patients with Exfoliation Syndrome". Ophthalmology. 89 (3): 214–218. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(82)34804-6. PMID 7088504.

- ^ Aasved, Henry (1971). "MASS SCREENING FOR FIBRILLOPATHIA EPITHELIOCAPSULARIS: so-called senile exfoliation or pseudoexfoliation of the anterior lens capsule". Acta Ophthalmologica. 49 (2): 334–343. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1971.tb00958.x. ISSN 1755-375X. PMID 5109796.

- ^ Shrum, K.R; Hattenhauer, M.G; Hodge, D (2000). "Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality associated with ocular pseudoexfoliation". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 129 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00255-X. PMID 10653417.

- ^ A, Elshnig (1922). "Ablosung der Zonulalamelle bei Glasblasern". Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 69: 732–734.

- ^ Schlötzer-Schrehardt, Ursula; Zenkel, Matthias (2019). "The role of lysyl oxidase-like 1 (LOXL1) in exfoliation syndrome and glaucoma". Experimental Eye Research. 189: 107818. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2019.107818. PMID 31563608.