Proximity fuze

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

A proximity fuze is a fuze that is designed to detonate an explosive device automatically when the distance to target becomes smaller than a predetermined value or when the target passes through a given plane. The proximity fuze should not be confused with the more commonly used contact fuse.

One of the first practical proximity fuzes was codenamed the VT fuze, an acronym of “Variable Time fuze”, as deliberate camouflage for its operating principle. The VT fuze concept in the context of artillery shells originated in the UK with British researchers (particularly Sir Samuel Curran[1]) and was developed under the direction of physicist Merle A. Tuve at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab (APL). The fuze is considered one of the most important technological innovations of World War II. The Germans were supposedly also working on proximity fuses in the 1930s, research and prototype work at Rheinmetal being halted in 1940 to devote available resources to projects deemed more necessary. Naval magnetic mines were introduced by the Germans during World War II.

History

Before the fuze's invention, detonation had to be induced either by direct contact, or a timer set at launch, or an altimeter. All of these have disadvantages. The probability of a direct hit with a relatively small moving target is low; to set a time- or height-triggered fuze one must measure the height of the target (or even predict the height of the target at the time one will be able to get a shell or missile in its neighbourhood). With a proximity fuze, all one has to worry about is getting a shell or missile on a trajectory that, at some time, will pass close by the target. This is still not a trivial task, but it is much easier to execute than previous methods.

Use of timing to produce air bursts against ground targets requires observers to provide information for adjusting the timing. This is not practical in many situations and is slow in any event. Proximity fuzes fitted to such weapons as artillery and mortar shells solve this problem by having a range of pre-set burst heights (e.g. 2, 4 or 10 metres, or about 7, 13, or 33 feet) above ground, which can be selected by gun crews prior to firing.

World War II

Design

After receiving a German prototype the radio frequency proximity fuze concept was proposed to the British Air Defence Establishment in a May 1940, memo from W. A. S. Butement, Edward S. Shire, and Amherst F.H. Thompson.[1] A breadboard circuit was constructed by the inventors and the concept was tested in the laboratory by moving a sheet of tin at various distances. Early field testing connected the circuit to a thyratron trigger operating a tower-mounted camera which photographed passing aircraft to determine distance of fuze function. Prototype fuzes were then constructed in June 1940, and installed in unrotated projectiles (the British cover name for solid fuelled rockets) fired at targets supported by balloons.[1] During 1940-42 a private venture initiative by Pye Ltd, a leading British wireless manufacturer, worked on the development of a radio proximity fuze. Pye's research was transferred to the United States as part of the technology package delivered by the Tizard Mission when the United States entered the war.[2] It is unclear how this work relates to other British developments. The details of these experiments were passed to the United States Naval Research Laboratory and National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) by the Tizard Mission in September 1940, in accordance with an informal agreement between Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt to exchange scientific information of potential military value.[1]

Following receipt of details from the British, the experiments were successfully duplicated by Richard B. Roberts, Henry H. Porter, and Robert B. Brode under the direction of NDRC section T chairman Merle Tuve.[1] Lloyd Berkner of Tuve's staff devised an improved fuze using separate tubes (British English: thermionic valves or just "valves") for transmission and reception. In December 1940, Tuve invited Harry Diamond and Wilbur S. Hinman, Jr, of the United States National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to investigate Berkner's improved fuze.[1] The NBS team built six fuzes which were placed in air-dropped bombs and successfully tested over water on 6 May 1941.[1]

Parallel NDRC work focused on anti-aircraft fuzes. Major problems included microphonic difficulties and tube failures attributed to vibration and acceleration in gun projectiles. The T-3 fuze had a 52% success against a water target when tested in January, 1942. The United States Navy accepted that failure rate and batteries aboard cruiser USS Cleveland (CL-55) tested proximity-fuzed ammunition against drone aircraft targets over Chesapeake Bay in August 1942. The tests were so successful that all target drones were destroyed before testing was complete.[1]

The German proximity fuze in development by Rheinmetall Borsig A.G. had the following characteristics:[3][4]

- The fuze was based on electrostatic principles. It is known that the nose of the shell was electrically insulated and isolated from the rest of the shell. The program was halted in 1940, restarted in early 1944 and then terminated again due to being overrun by the Allies at the point that it was ready for production.

- Initial fuze testing demonstrated a sensitivity of 1–2 meters and a reliability of 80% when fired against a metal cable target. A circuit adjustment yielded an increase to 3–4 meters and a reliability of close to 95%. Further work showed a 10-15 meter sensitivity. This was with 88mm cannon shells. The shell to all intents and purposes was ready for production.

The shell probably could not have been easily degraded by jamming or chaff, unlike the Allied shell.

In contrast, the Allied fuze workings:

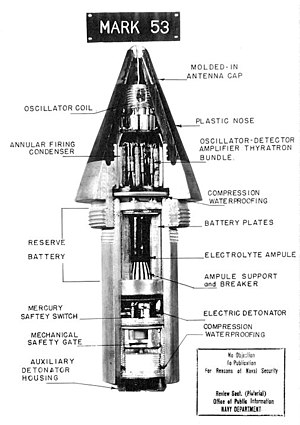

- Technically, the Allied fuze used constructive and destructive interference to detect its target.[5] The design had 4 tubes.[6] One tube was an oscillator connected to an antenna that would both transmit and receive. When there was no target nearby, the received signal would be small and have little effect on the circuit. When a target was nearby, it would reflect a portion of the oscillator's signal back to the fuze. This reflected signal would affect the oscillator depending on the round trip distance from the fuze to the target. If the reflected signal were in phase, the oscillator amplitude would increase and the oscillator's plate current would also increase. If the reflected signal were out of phase, then the plate current would decrease. When the distance between the fuze and the target changed rapidly, the phase relationship also changed. A low frequency signal developed at the oscillator's plate. Two additional amplifiers detected this low frequency and triggered the 4th tube (a gas-filled thyratron) to set off the detonator. There were many shock hardening techniques including planar electrodes and packing the components in wax and oil to equalize the stresses.

Production

First large scale production of tubes for the new fuzes[1] was at a General Electric plant in Cleveland, Ohio formerly used for manufacture of Christmas-tree lamps. Fuze assembly was completed at General Electric plants in Schenectady, New York and Bridgeport, Connecticut.[7]

By 1944 a large proportion of the American electronics industry concentrated on making the fuzes. Procurement contracts increased from $60 million in 1942, to $200 million in 1943, to $300 million in 1944 and were topped by $450 million in 1945. As volume increased, efficiency came into play and the cost per fuze fell from $732 in 1942 to $18 in 1945. This permitted the purchase of over 22 million fuzes for approximately $1,010 million. The main suppliers were Crosley, RCA, Eastman Kodak, McQuay-Norris and Sylvania.[8]

Deployment

Vannevar Bush, head of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) during this war, credited the proximity fuze with three significant effects:[9]

- First, it was important in defense from Japanese Kamikaze attacks in the Pacific. Bush estimated a sevenfold increase in the effectiveness of 5-inch antiaircraft artillery with this innovation.[10]

- It was an important part of the radar-controlled antiaircraft batteries that finally neutralized the German V-1 bomb attacks on England.[10]

- Third, it was released for use in Europe just before the Battle of the Bulge. At first the fuzes were only used in situations where they could not be captured by the Germans. They were used in land-based artillery in the South Pacific in 1944. They were incorporated into bombs dropped by the U.S. Air Force on Japan in 1945, and they were used to defend Britain against the V-1 attacks of 1944, achieving a kill ratio of about 79%. (They were ineffective against the much faster V-2 missiles.) There was no risk of a dud falling into enemy hands. The Pentagon decided it was too dangerous to have a fuze fall into German hands because they might reverse engineer it and create a weapon that would destroy the Allied bombers, or at least find a way to jam the radio signals. Therefore they refused to allow the Allied artillery use of the fuzes in 1944.

- General Dwight D. Eisenhower protested vehemently and demanded he be allowed to use the fuzes. He prevailed and the VT fuzes were first used in the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, when they made the Allied artillery far more devastating, as all the shells now exploded just before hitting the ground. It decimated German divisions caught in the open. The Germans felt safe from timed fire because they thought that the bad weather would prevent accurate observation. U.S. general George S. Patton said that the introduction of the proximity fuze required a full revision of the tactics of land warfare.[11]

- The Germans started their own independent research in the 1930s but the programme was cut in 1940 likely due to the 'fuhrer directive' (Führerbefehl) that, with few exceptions, stipulated all work that could not be put into production within 6 months was to be terminated to increase resources for those projects that could (in order to support operation Barbarossa). It was at this time that the Germans also abandoned their magnetron and microwave development teams and programs. Many other advanced and experimental programs also suffered. Upon resumption of research and testing by Rheinmetall in 1944 the Germans managed to develop and test fire several hundred working prototypes before the war ended.

Radio frequency sensing

Radio frequency sensing is the main sensing principle for artillery shells.

The device described in the WWII patent[12] works as follows: The shell contains a micro-transmitter which uses the shell body as an antenna and emits a continuous wave of roughly 180–220 MHz. As the shell approaches a reflecting object, an interference pattern is created. This pattern changes with shrinking distance: every half wavelength in distance (a half wavelength at this frequency is about 0.7 meters), the transmitter is in or out of resonance. This causes a small oscillation of the radiated power and consequently the oscillator supply current of about 200–800 Hz, the Doppler frequency. This signal is sent through a band pass filter, amplified, and triggers the detonation when it exceeds a given amplitude.

Optical sensing

Optical sensing was developed in 1935, and patented in Great Britain in 1936, by a Swedish inventor, probably Edward W. Brandt, using a petoscope. It was first tested as a part of a detonation device for bombs that were to be dropped on bombers, part of the UK's Air Ministry's "bombs on bombers" concept. It was considered (and later patented by Brandt) for use with anti-aircraft missiles. It used then a toroidal lens, that concentrated all light out of a plane perpendicular to the missile's main axis onto a photo cell. When the cell current changed a certain amount in a certain time interval, the detonation was triggered.

Some modern air-to-air missiles use lasers. They project narrow beams of laser light perpendicular to the flight of the missile. As the missile cruises towards the target the laser energy simply beams out into space. As the missile passes its target some of the energy strikes the target and is reflected back to the missile where detectors sense it and detonate the warhead.

Acoustic sensing

Acoustic sensing used a microphone in a missile. The characteristic frequency of an aircraft engine is filtered and triggers the detonation. This principle was applied in British experiments with bombs, anti-aircraft missiles, and airburst shells (circa 1939). Later it was applied in German anti-aircraft missiles, which were mostly still in development when the war ended.

The British used a Rochelle salt microphone and a piezoelectric device to trigger a relay to detonate the projectile or bomb's explosive.

Naval mines can also use acoustic sensing, with modern versions able to be programmed to "listen" for the signature of a specific ship.

Magnetic sensing

Magnetic sensing can only be applied to detect huge masses of iron such as ships. It is used in mines and torpedoes. Fuzes of this type can be defeated by degaussing, using non-metal hulls for ships (especially minesweepers) or by magnetic induction loops fitted to aircraft or towed buoys.

Pressure sensing

Some naval mines are able to detect the pressure wave of a ship passing overhead.

VT and "Variable Time"

The designation "VT" is often said to refer to "variable time". Fuzed munitions before this invention were set to explode at a given time after firing, and an incorrect estimation of the flight time would result in the munition exploding too soon or too late. The VT fuze could be relied upon to explode at the right time—which might vary from that estimated.

One theory is that "VT" was coined simply because Section "V" of the Bureau of Ordnance was in charge of the programme and they allocated it the code-letter "T".[13] This would mean that the initials also standing for "variable time" was a happy coincidence that was supported as an intelligence smoke screen by the allies in WW2 to hide its true mechanism.

An alternative is that it was deliberately coined from the existing "VD" (Variable Delay) terminology by one of the designers.[14]

Gallery

-

120mm HE mortar shell fitted with M734 proximity fuze

-

60mm HE mortar shell fitted with proximity fuze

-

A 155mm artillery fuze with selector for point/proximity detonation (currently set to proximity).

See also

- Contact fuse

- M734 proximity fuze

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Brennen, James W. (September 1968), The Proximity Fuze Whose Brainchild?, United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- ^ http://www.pyetelecomhistory.org/prodhist/military/military.html

- ^ Truth About the Wunderwaffen by Igor Witowski

- ^ CIOS report ITEM no 3 file no XXVI -1 (1945)

- ^ Bureau of Ordinance (1946, pp. 32–37)

- ^ Bureau of Ordinance (1946, p. 36) shows a fifth tube, a diode, used for a low trajectory wave suppression feature (WSF).

- ^ Miller, John Anderson (1947), Men and Volts at War, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company

- ^ Sharpe (2003)

- ^ Bush (1970, pp. 106–112)

- ^ a b Bush (1970, p. 109)

- ^ Bush (1970, p. 112)

- ^ Radio Proximity Fuze, retrieved 2008-07-13

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|country-code=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|issue-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|patent-number=ignored (help) - ^ Ian Hogg. British and American Artillery of WW2.

- ^ http://www.navweaps.com/index_tech/tech-102.htm Proximity Fuze - what does "VT" mean?.

- Baxter, James Phinney (1968) [1946], Scientists Against Time, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0262520126

- Bureau of Ordnance (May 15, 1946), VT Fuzes For Projectiles and Spin-Stabilized Rockets, Ordnance Pamphlet, vol. OP 1480, U. S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance

- Bush, Vannevar (1970), Pieces of the Action, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

- Sharpe, Edward A. (2003), "The Radio Proximity Fuze: A survey", Vintage Electrics, 2 (1)

Further reading

- Baldwin, Ralph B. (1980), The Deadly Fuze: Secret Weapon of World War II. Baldwin was a member of the (APL) team headed by Tuve that did most of the design work.

- Bennett, Geoffrey (1976), "The Development of the Proximity Fuze", Journal of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies, 121 (1): 57–62, ISSN 0953-3559

- Collier, Cameron D. (1999), "Tiny Miracle: the Proximity Fuze", Naval History, 13 (4), U. S. Naval Institute: 43–45, ISSN 1042-1920 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Moye, William T. (2003), Developing the Proximity Fuze, and Its Legacy, U.S. Army Materiel Command, Historical Office

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) [dead link] link broken April 30, 2010

External links

- Navy Historical Centre - Radio Proximity (VT) Fuzes

- http://www.amc.army.mil/amc/ho/studies/fuze.html [dead link]

- Southwest Museum of Engineering,Communications and Computation - The Radio Proximity Fuze - A survey

- Southwest Museum of Engineering,Communications and Computation - Proximity Fuze History

- The Pacific War: The U.S. Navy-The Proximity (Variable-Time) Fuze

- The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

11100 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, Maryland 20723

• 240-228-5000 (Washington, DC, area) • 443-778-5000 (Baltimore area)