President of Austria

| President of Austria Bundespräsident der Republik Österreich | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

since 26 January 2017 | |

| Style | Mr President His Excellency |

| Type | Head of state |

| Status | Supreme executive organ |

| Member of | Presidential Chancellery |

| Seat | Leopoldine Wing, Hofburg Imperial Palace Innere Stadt, Vienna |

| Nominator | Political parties or self-nomination |

| Appointer | Direct popular vote sworn in by the Federal Assembly |

| Term length | Six years, renewable once |

| Constituting instrument | Constitution of Austria |

| Precursor | Chair of the Constituent National Assembly |

| Formation | 10 November 1920 |

| First holder | Michael Hainisch |

| Succession | Line of succession |

| Salary | €349,398 annually |

| Website | www.bundespraesident.at |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Austria |

|---|

|

The president of Austria (Template:Lang-de) is the head of state of the Republic of Austria. Though theoretically entrusted with great power by the Constitution, in practice the president is largely a ceremonial and symbolic figurehead.

The office of the president was established in 1920 following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Habsburg monarchy in 1918. As head of state, the president succeeded the chair of the Constituent Assembly, the post-monarchic provisional legislature. Originally intended to be chosen directly by the Austrian people through universal suffrage every six years, the president was instead appointed by the legislative Federal Assembly until 1951, when Theodor Körner became the first popularly-elected president. Since the institution of the popular vote, only nominees of the Social Democratic Party and the People's Party had been elected to the presidency, with the exception of the Green-endorsed incumbent Alexander Van der Bellen.

The president appoints the chancellor, the vice chancellor, the ministers, the secretaries of state, and the justices of the Supreme Courts. The president can also remove the chancellor and the Cabinet at any time. Additionally, the president signs bills into law and is empowered to dissolve the National Council and the state legislatures, sign treaties with foreign countries, rule by emergency decree, and command the Armed Forces. However, most of these presidential powers have never been applied. Furthermore, the president ranks first in Austria's order of precedence, ahead of the presidium of the National Council and the chancellor.

The principal residence and workplace of the president is the Leopoldine Wing of the Hofburg Imperial Palace, situated in Vienna.

History

Background

Prior to the collapse of the multinational Austro-Hungarian Empire towards the end of World War I, what now is the Republic of Austria had been part of a monarchy with an emperor as its head of state and chief executive. The empire noticeably began to fracture in late 1917 and manifestly disintegrated into a number of independent rump states over the course of the following year.[1]

As the emperor had grown practically powerless, the members of the lower chamber of the Imperial Council – representing Cisleithania, the empire's ethnically German provinces – formed a Provisional National Assembly for their paralyzed country on 21 October 1918.[2][3] The National Assembly appointed three coequal chairmen, one of them being Karl Seitz, and established a State Council to administer the executive branch.[4]

On 11 November, Emperor Charles I dissolved the Imperial Cabinet and officially renounced any participation in government affairs but did not abdicate, seeing this move only as a temporary break from his rule.[5][6] However, the next day, the National Assembly proclaimed the Republic of German-Austria, thus effectively ending the monarchy.[7][8] The State Council assumed the remaining powers and responsibilities of the emperor that day, while the three assembly chairmen – as chairmen of the State Council – became the country's collective head of state.

Establishment

On 4 March 1919, the Constituent National Assembly, the first parliament to be elected by universal suffrage, convened and named Seitz its chairman a day later.[9][10] The National Assembly disbanded the State Council on 15 March – hence Seitz became the sole head of state[11] – and began drafting a new Constitution the same year. The Christian Social Party advocated for creating a presidency with comprehensive executive powers, similar to those of the president of the Weimar Republic. However, the Social Democratic Worker's Party, fearing that such a president would become a "substitute emperor", favored reverting to a parliamentary presidium acting as collective head of state. In the end, the framers of the Constitution opted for a presidency that is separate from the legislature but bears not even nominal authority.[12]

On 1 October, the Federal Constitutional Law, the centerpiece of the new Constitution, was ratified by the National Assembly and on 10 November, it became effective, making Seitz president of Austria in all but name.[13] The new Constitution established that president is to be elected by the Federal Assembly, a joint session of both houses of the now-bicameral Parliament. On 9 December 1920, the Federal Assembly elected Michael Hainisch to become the first president of Austria.[14]

First Republic

The parliamentary system erected by the new Constitution was highly unpopular. This led to surging support for the authoritarian and paramilitary Heimwehr movement, which preferred a system granting substantially more powers to the president. On 7 December 1929, under growing pressure from the Heimwehr, the Constitution was amended to give the president sweeping executive and legislative authority.[16][17] Although most of these powers were to be exercised through the ministers, on paper the president now had powers equivalent to those of presidents in presidential systems. It also called for the office to be elected by popular vote and expanded the president's term to six years. The first election was scheduled for 1934. However, owing to the financial ramifications of the Great Depression, all parties agreed to suspend the election in favor of having Wilhelm Miklas reelected by the Federal Assembly.[18]

Three years later, Engelbert Dollfuss and the Fatherland Front tore down Austrian parliamentarism altogether, formally annulling the Constitution on 1 May 1934.[19] It was replaced by an authoritarian and corporatist system of government that concentrated power in the hands of the chancellor, not the president. Miklas was stripped of the authority he had gained in 1929, but agreed to act as a figurehead for the sake of institutional continuity anyway. He was not entirely powerless, however; during the Anschluss crisis, he provided some of the stiffest resistance to Nazi demands.[20] He technically remained in office until 13 March 1938, the day Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany and thus lost its sovereignty.

When Austria re-established itself as an independent state on 27 April 1945, the party leaders forming the provisional government decided not to write a new Constitution, instead restoring that of 1920, as amended in 1929.[21] Even though this revision was still somewhat controversial at that point, it was part of Austria's most recent constitutional framework, giving it at least some much-needed form of democratic legitimacy. The party leaders were also afraid that lengthy discussion might provoke the Red Army, then in control of Vienna, to barge in and impose Communist rule. The Constitution thus reenacted, effective 1 May, therefore still entailed the provision calling for popular election of the president. Following the November 1945 legislative election, however, the Federal Assembly temporarily suspended this provision and installed Karl Renner as the president of Austria as of 20 December.[22] The suspension in question seemed to have been motivated mainly by a lack of money; no attempt was ever made to prolong it, and Renner had already been the universally accepted, de facto head of state anyway. Starting with the 1951 election of Renner's successor Theodor Körner, all presidents have in fact been elected by the people.[23]

Second Republic

The presidency of Adolf Schärf was characterized by strict nonpartisanship, which created a precedent that lasts to this day. Since the Second Republic, presidents have taken an increasingly passive role in day-to-day politics and are rarely ever the focus of the press, except during presidential elections and political upheavals. A notable exception was Kurt Waldheim, who became the subject of international debate and controversy, after his service in the Sturmabteilung and the Wehrmacht garnered widespread public attention.[24] Another exception was Thomas Klestil, who attempted to assume a far more active political role. He called for the grand coalition to remain in power and demanded to represent Austria in the European Council but ultimately failed on both counts.[25]

Election

Procedure

The president of Austria is elected by popular vote for a term of six years and is limited to two consecutive terms of office.[26][27][28][29] Voting is open to all people entitled to vote in general parliamentary elections, which in practice means that suffrage is universal for all Austrian citizens over the age of sixteen that have not been convicted of a jail term of more than one year of imprisonment. (Even so, they regain the right to vote six months after their release from prison.)

Until 1 October 2011, with the exception of members of any ruling or formerly ruling dynastic houses (a measure of precaution against monarchist subversion, and primarily aimed at members of the House of Habsburg), anyone entitled to vote in elections to the National Council who is at least 35 years of age is eligible for the office of president. The exception of ruling or formerly ruling dynasties has been abolished meanwhile within the Wahlrechtsänderungsgesetz 2011 (Amendment of the law on the right to vote 2011) due to an initiative by Ulrich Habsburg-Lothringen.[30]

The president is elected under the two-round system. This means that if no candidate receives an absolute majority (i.e. more than 50%) of valid votes cast in the first round, then a second ballot occurs in which only those two candidates who received the greatest number of votes in the first round may stand. However, the constitution also provides that the group that nominates one of these two candidates may instead nominate an alternative candidate in the second round. If there is only one candidate standing in a presidential election then the electorate is granted the opportunity to either accept or reject the candidate in a referendum.

While in office the president cannot belong to an elected body or hold any other position.

Oath of office

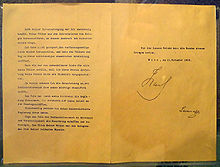

Article 62 of the Austrian Constitution provides that the president must take the following oath or affirmation of office in the presence of the Federal Assembly (although the addition of a religious asseveration is admissible):[31][32]

I solemnly swear that I will faithfully observe the Constitution and all the laws of the Republic and fulfill my duty to the best of my knowledge and conscience.

Latest elections

Powers and duties

Presidential powers and responsibilities are chiefly established by the Federal Constitutional Law,[33][34] additional powers may be defined by federal statute, judicial interpretations and legal precedents. While the Austrian political system as a whole can often be compared with that of Germany, the Austrian presidency can hardly be compared with the German one; since the president of Austria has much more power. The president of Austria appoints the head of government and their Cabinet, can dismiss the head of government and their Cabinet, appoints the highest-ranking government officials, signs bills into law, and is the military commander-in-chief.

Executive role

Appointing the Cabinet

The president appoints the chancellor, the vice chancellor, and the ministers, which collectively form the Cabinet of Austria.[35][36]

A new National Council, the powerful lower chamber of Parliament, is elected at least every five years by universal suffrage. Following such an election the president conventionally charges the chancellor candidate[a] of the party that won either an absolute majority or a plurality of seats with the formation of a new Cabinet. Theoretically, the president could appoint any adult citizen (with some minor constraints) chancellor of Austria. However, the National Council can adopt a motion of no confidence against the chancellor, a minister, or the entire Cabinet at any time, thus substantially limiting the president's actual options.

If the winning party did not receive an absolute majority (the common electoral outcome since 1983), the victor will search for a junior coalition partner, to create a politically stable Cabinet that commands the support of the National Council. This process will kick off with a series of rather brief "exploratory discussions" (Sondierungsgespräche) with all parties, which usually lasts several weeks. During this time, the victor will commonly look out for the party that demands the least ministerial posts and is the most willing to compromise. The victor will subsequently enter more serious and comprehensive "coalition negotiations" (Koalitionsverhandlungen) with that party, a process usually lasting several months. During the coalition negotiations, both parties most produce a cabinet agenda (Regierungsprogramm), a coalition contract (Koalitionsvertrag), and a ministers' list (Ministerliste), which defines the Cabinet's composition; the victor commonly claims the chancellorship, while leader of the junior coalition party commonly asserts the vice chancellorship and an additional ministerial position.

The list is then introduced to the president, who can either accept or reject it. If the president accepts, the new Cabinet will be appointed and officially sworn in at an inauguration ceremony about a week later. If the president rejects the list, there are several possibilities; the president asks the victor to rewrite the list and/or omit certain nominees, the president strips the victor of their responsibility to form a Cabinet and charges someone else, or the president calls a new legislative election.

So far, there have only been three cases where a president refused to appoint a Cabinet nominee; Karl Renner denied to re-appoint a minister suspected of corruption, Theodor Körner dismissed the call of Chancellor Leopold Figl to appoint a Cabinet with the participation of the far-right Federation of Independents, Thomas Klestil declined to appoint a ministerial nominee involved in criminal proceedings and a ministerial nominee who had made frequent extremist and xenophobic statements.

Dismissing the Cabinet

The president can dismiss the chancellor or the entire Cabinet at any time, such at will. However, individual Cabinet members can only be dismissed by the president on the advice of the chancellor.[35][36] So far, the dismissal of an entire Cabinet against its will has never occurred. President Wilhelm Miklas did not make use of this power when Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß absolished the Constitution to establish the dictatorial Federal State of Austria.

The removal of a minister against their will occurred only once, when Chancellor Sebastian Kurz asked President Alexander Van der Bellen to remove Interior Minister Herbert Kickl. Ensuing the Ibiza affair and a likely collapse of the Cabinet, Kickl swiftly appointed Peter Goldgruber – with whom he had close ties – to the office of director general for the Public Security, which would have indefinitely granted him direct operational control over the vast majority of Austrian law enforcement agencies.[b][37][38] President Alexander Van der Bellen refused to assent Goldgruber's appointment – following a convention to avoid high-level appointments during transition periods – thus preventing him from taking office. [39]

Appointing federal and state officials

From the official and legal point of view, the president appoints all officers of the federal government, not just the members of Cabinet and the justices of the supreme courts. This includes all military officers and soldiers, all judges, as well as all ordinary functionaries and bureaucrats.[40][41] In practice however, this power of appointment is delegated to the ministers and their subordinates, although the highest-ranking officers of government are always personally appointed by the president.[42][43]

Because the governors of the states do not only serve as the chief executives of their respective state but also as the chief representatives of the federal government within that state, the president swears in all governors, following their election by the state diet.

Legislative role

Signing bills into law

As state notary of Austria, the president signs bills into law.[44][45] Signing bills into law is a constitutionally mandated duty of the president and not a discretionary power; it is not comparable with the presidential veto in the United States or the Royal Assent in the United Kingdom. In their capacity as state notary, the president scrutinises the constitutionality of the lawmaking process undertaken to enact a piece of legislation. If the president finds the bill to have been crafted in an unconstitutional way, the president is compelled to deny their signature, which strikes down the piece of legislation. All bills on federal level, no matter if they affect statutory or even constitutional law, must be signed by the president to take effect.

The president generally does not verify if an enacted statute complies with constitutional law; that is subject to the Constitutional Court, once the statute becomes effective and is legally challenged. Judicial interpretations regarding the scrutiny extent of this presidential responsibility have varied, with some arguing that the president may deny signature if provisions of an enacted statute are undoubtedly unconstitutional. President Heinz Fischer established a precedent for that, by refusing to sign a statute – containing retrospective criminal provisions – into law; this remains the only time a president has denied signature.

Once a bill is introduced in Parliament, it must pass the National Council with the requisite quorums and be approved by the Federal Council to become 'enacted'.[46] After its enactment the bill is forwarded to the chancellor, who submits it to the president. The president then signs the bill into law (if it has been enacted in accordance with constitutional requirements).[47] The chancellor subsequently countersigns and then promulgates the bill in the federal law gazette, ultimately rendering it effective.[48][49]

If the president refuses to sign any or particular bills into law – that are not in obvious or direct violation of the Constitution – the president may be impeached by the Federal Assembly before the Constitutional Court and subsequently removed from office through conviction for failing their constitutional responsibilities.

Dissolving the National Council

The president may dissolve the National Council at the request of Cabinet, but only once for the same reason.[50][51] The legal consequences of a dissolution of the National Council by the president differ from those of a parliamentary self-dissolution. If the president terminates the legislative period, the National Council is immediately dissolved and thereby incapacitated. However, the Standing Subcommittee of the National Council's Principal Committee remains as an emergency body until the newly-elected National Council convenes. Prior to that, the president may issue emergency decrees on the request of the Cabinet and with the consent of the Standing Subcommittee of the Principal Committee. In the case of self-dissolution, the old National Council keeps meeting until a new one is elected.

So far, only President Wilhelm Miklas has made use of this power, after the Christian Social Party had lost its coalition partner and thus a majority in Parliament.

Dissolving state diets

The president can dissolve every state diet at the request of Cabinet and with the consent of the Federal Council.[52][53] However, the president may only do so once for the same reason; as with the dissolution of the National Council. The Federal Council must agree to the dissolution by a two-thirds majority. The delegation of the state whose diet is to be dissolved, may not partake in the vote.

The dissolution of a state diet is viewed as an encroachment on federalism, as the national government directly intervenes into state affairs. Like with the presidential dissolution of the National Council, a dissolved state diet is considered incapacitated until after a new election. This power has never been applied by any president yet.

Rule by decree

The president is authorized to rule by emergency decree in times of crisis.[54][55] The Constitution states as follow:

To ward off irreparable damages to the general public, at a time where the National Council is not in session and cannot be convened in time, at the request of the Cabinet, and with the assent of the Standing Subcommittee of the Principal Committee of the National Council, the president is empowered to adopt provisional regulations that have the force of law.

Such emergency decrees do not affect the Constitution – which chiefly consists of the Federal Constitutional Law and the Basic Human Rights – as well as any other important legal provision. As soon as the National Council is in session again, it is ought to immediately approve or invalidate active emergency decrees. The power to rule by decree has never been applied yet.

Judicial role

Enforcer of the Constitutional Court

The president is entrusted with the enforcement of findings of fact of the Constitutional Court, when such enforcement is not subject to ordinary courts.[56][57] The request for enforcement is submitted to the president by the Court itself. The Constitution provides the president with extensive enforcement powers. Enforcement jurisdiction can comprise state and federal authorities (this includes the Armed Forces and law enforcement) as well as a state or the republic in its entirety. When wielding enforcement rights, the president obtains direct operational control over the authorities concerned. If a federal authority or the republic as a whole are affected, the president does not require countersignature.

Appointing justices

The president appoints the president, the vice president, the six further justices, and the three substitute justices of the Constitutional Court on the nomination of Cabinet; additionally, the president appoints three justices and two substitute justices on the nomination of the National Council and three justices and one substitute justice on the nomination of the Federal Council.[58][59] The president also appoints the president, the two vice presidents, the 14 presiding justices, and the 43 further justices of the Supreme Court of Justice; as well as the president, the vice president, the presiding justices, and the further justices of the Supreme Administrative Court on the nomination of Cabinet, of which all members expect the president and vice president are recommended to Cabinet by the Court itself.[60]

Diplomatic role

The president is the chief diplomat of Austria and may negotiate and sign treaties with foreign countries; some treaties require the assent of the National Council.[61][62]

When Austria joined the European Union, President Thomas Klestil and Chancellor Franz Vranitzky had a disagreement on who would represent Austria in the European Council. Ultimately, the chancellor's point of view prevailed, mainly due to legal and practical reasons. However, President Klestil argued that he had only delegated this power of representation to the chancellor.

Military role

The president is the commander-in-chief of the Austrian Armed Forces. While there is no clear juridical or scholarly consensus on the exact constitutional meaning and extent of this power, the majority of legal scholars believe that the president may, in this capacity, exercise ultimate operational direction over the Armed Forces.[63]

Article 80 of the Constitution establishes how the military is to be governed. Clause 1 of that article states "the President shall have Supreme Authority over the Armed Forces", Clause 2 that "if not the President bears disposal authority, the [Minister of Defense] shall have disposal authority within a scope of responsibility defined by the Cabinet", and Clause 3 that "command authority over the military shall be vested in the [Minister of Defense]".[64][65]

The Constitution hence distinguishes between three different types of military authority: "command authority" (Befehlsgewalt), the power to issue verbal or written directives; "disposal authority" (Verfügungsgewalt), the power to define the organization, tasks, and missions of the Armed Forces or individual military units; and "supreme authority" (Oberbefehl).[66] The latter one – which Clause 1 vests in the presidency – has particularly been ambiguous and inconclusive.[67]

As no president has ever made use of this power, precedents were never established. Day-to-day military operations are administered by the minister of defense, who is widely seen as de facto commander-in-chief,[68][69] while defense policy and key decisions are made by the Cabinet as a whole.

As commander-in-chief, the president succeeds the emperor of Austria in his capacity as supreme commander of the Austro-Hungarian military. Following the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy, the Principal Committee of the newly established National Council began serving as the main decision-making body of the Armed Forces. In 1929, the Christian Social Party transferred supreme military authority from the Principal Committee to the president.

Ceremonial role

The president has various additional powers and duties, which are typically vested in a head of state. These include, for example, the creation and conferment of honorary and professional titles, and the basically meaningless right to legitimise illegitimate children at the request of their parents.[61][62] Another power is the bestowal of the Promotio sub auspiciis Praesidentis rei publicae, a golden ring serving as the highest possible distinction and decoration for doctoral students with the most extraordinary credentials. Furthermore, the president is empowered to strike down criminal cases ("right of abolition") and to grant pardons and commutations. According to case law of the Constitutional Court, presidential pardons do not only void the sentence but also undo the conviction.[70]

Incumbency

Immunity

The president enjoys full sovereign immunity from any type of official prosecution, including civil suit and criminal prosecution. The president may only be prosecuted with the explicit consent of the Federal Assembly. If a government authority intends to prosecute the president, it must refer a request for extradition to the National Council. If the National Council approves, the chancellor must convene the Federal Assembly, which will then decide over the request for extradition.[71][72]

Removal

Popular deposition

The ordinary way of removing a sitting president from office would be through popular deposition. Since the president is elected by the people, the people also have the power to remove the president again through a plebiscite.[73][74]

Popular deposition commences with an act of the National Council requesting the convocation of the Federal Assembly. Such a resolution of the National Council is passed with a supermajority, meaning it requires the same quorums as when amending constitutional law; the attendance of at least half of the members of the National Council and a successful two-thirds vote. If passed, the president is automatically unable to "further exercise the powers and duties of the presidency" and thereby deprived of all authority, the chancellor in turn, is required to immediately call a session of the Federal Assembly. Once convened, the Federal Assembly then considers and decides over the National Council's request of administering a plebiscite.

If a plebiscite is conducted and turns out successful, the president is removed from office. However, if the plebiscite fails the Constitution treats it as a new legislative election, which triggers the immediate and automatic dissolution of the National Council; even in such a case, the president's term of office may not exceed twelve years in total.

Impeachment

The president can be impeached before the Constitutional Court by the Federal Assembly for violating constitutional law.[75][76] This process is triggered by either a resolution of the National Council or the Federal Council. Upon the passage of such a resolution, the chancellor is required to call a session of the Federal Assembly, which then considers the impeachment of the president. A supermajority is needed to impeach the president, meaning the attendance of at least half of the members of the National Council and the Federal Council as well as a successful two-thirds vote are required.[77][78]

If the Federal Assembly decides to impeach the president, it acts as the plaintiff before the Constitutional Court. If the Court convicts the president of having breached constitutional law, the president is automatically removed from office. Conversely, if the Court finds the president to have committed a minor offense, the president remains in office and is merely reprimanded.

Succession

| Part of a series on Orders of succession |

| Presidencies |

|---|

The Constitution of Austria makes no provisions for an office of vice president. Should the president become temporarily incapacitated – undergoes surgery, becomes severely ill, or visits a foreign country (excluding EU member states) – presidential powers and duties devolve upon the chancellor for a period of twenty days, although the chancellor does not become "acting president" during that time.

The powers and duties of the presidency devolve upon the Presidium of the National Council in the following three cases:

- The aforementioned period of twenty days expires, in which case the Presidium assumes presidential powers and duties on the twenty-first day;[79][80]

- The office is vacated because the president dies, resigns, or is removed from office, in which case the Presidium assumes presidential powers and duties immediately;

- The president is prevented from "further exercising the powers and duties of the presidency" because the National Council has requested the convocation of the Federal Assembly to consider the popular deposition of the president, in which case the Presidium also assumes presidential powers and duties immediately.

When exercising the powers and duties of the presidency, the three presiding officers of the National Council – forming the Presidium – act collectively as a collegiate body. If votes are divided equally, the higher-ranking presiding officer's vote takes precedence.

Compensation

The president is compensated for his or her service with €349,398 annually, the chancellor in turn is compensated with €311,962 annually.[81] This amount is particularly high when considering that the chancellor of Germany (€251,448),[82] the president of France (€179,000),[83] the prime minister of the United Kingdom (€169,284),[84] and the president of Russia (€125,973) receive a significantly lesser salary, although they are the chief executives of substantially larger countries; the Austrian president's salary is topped only by that of the president of the United States (€370,511).[85][86]

Residence

The principal residence and workplace of the president is the Leopoldine Wing in the Hofburg Imperial Palace, which is located in the Innere Stadt of Vienna.[87] The Leopoldine Wing is sometimes ambiguously referred to as the "Presidential Chancellery". In practice, the president does not actually reside in the Hofburg but retains their personal home.

As its full name already divulges, the Hofburg is an edifice stemming from the times of the monarchy; it was built under Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I in the 13th century. Ensuing the fall of the monarchy and the formation of the republic, democratic institutions intentionally kept their distance from monarchic establishments and so the original residence of the president became the chancellery building. However, following a severe bombardment during World War II, the chancellery building became uninhabitable and the president had to find new lodging. The first president of the Second Republic, Karl Renner, deliberately chose the Leopoldine Wing; as its creation and history – in particular the interior design – was majorly influenced by Empress Maria Theresia, whose profile was generally favorable among the people at the time. The chancellery building was later renovated and now serves as the residence and workplace of the chancellor.

Today, the Leopoldine Wing harbours the offices of the Presidential Chancellery on its second and third floor. Additionally to the Hofburg, the president has a summer residence at their disposal, the Mürzsteg Hunting Lodge. Although former President Heinz Fischer pledged to sell the building while campaigning for the presidency,[88] the lodge has been used by him and his successor to host guests and foreign dignitaries.[89][90]

Protection

The president is legally protected by multiple special criminal law provisions; of which the most important is § 249 of the statutory Criminal Code:[91][92]

Anyone who attempts depose the President by force or dangerous threats or to use one of these means to coerce or prevent the exercise of his powers, in part or in their entirety, is subject to imprisonment from one to ten years.

Furthermore, the title Bundespräsident (federal president) may – even with additions or in connection with other titles – not be used by anyone other than the incumbent president.

Chancellery

The president heads the Presidential Chancellery, a small executive branch body with the purpose of aiding the president in exercising and carrying out their powers and duties.[93] The Presidential Chancellery shouldn't be confused with the Federal Chancellery, a substantially larger executive branch organization reporting to the chancellor.[94] The Presidential Chancellery is the only government body the president actually directs without being constrained by the requirement for advise and countersignature. The term "Presidential Chancellery" is sometimes interchangeably used with "Leopoldine Wing", the seat of the president and the Presidential Chancellery.[95]

List of presidents

See also

- History of Austria

- Politics of Austria

- Chancellor of Austria

- List of chancellors of Austria

- Vice-Chancellor of Austria

- Emperor of Austria

Notes

- ^ Which is commonly party leader.

- ^ Which is generally of professional and permanent nature

References

- ^ "Zerfall der Habsburger-Monarchie: Nicht nur der Krieg war schuld". DER STANDARD (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Watson. Ring of Steel. pp. 536–40.

- ^ "21. Oktober 1918: Die Provisorische Nationalversammlung konstituiert sich | Parlament Österreich". parlament.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "ÖNB-ALEX - Staatsgesetzblatt 1918-1920". alex.onb.ac.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ otto.klambauer (5 December 2011). "Habsburger Abdankung und Exil". kurier.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Der letzte Kaiser verließ Österreich unter "feierlichem..." Die Presse (in German). 22 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "12. November 1918: Die Ausrufung der Republik | Parlament Österreich". parlament.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "30. Oktober 1918: Deutschösterreich tritt ins Licht | Parlament Österreich". parlament.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Erste Nationalratswahl". hdgö - Haus der Geschichte Österreich. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Die ersten weiblichen Abgeordneten der Ersten Republik". DER STANDARD (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Kennen Sie die bisherigen Amtsinhaber?". Bundespräsident (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Ucakar, Karl; Gschiegl, Stefan (2010). Das politische System Österreichs und die EU (in German) (2 ed.). p. 125.

- ^ "Das Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz | Parlament Österreich". parlament.gv.at. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "MICHAEL HAINISCH, EX-HEADOFAUSTRIA; First President of Nation's Republic, Who Foresaw Its Downfall, Dies at 81 URGED UNION OF GERMANS Rejoiced When Nazis Annexed His Country, Which He Led in Stormy Years, 1920-28 (Published 1940)". The New York Times. March 1940. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Austria - Authoritarianism: Dollfuss and Schuschnigg". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Bundes-Verfassungsnovelle 1929". hdgö - Haus der Geschichte Österreich. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Österreich, eine "halbpräsidentiale" Republik?". DER STANDARD (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Präsident Zauderer". DER STANDARD (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Der Staat der Mai-Verfassung: Auf Sand gebaut". DER STANDARD (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

- ^ "1945 - Wiederherstellung der Republik Österreich | Parlament Österreich". parlament.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Panzl-Schmoller, Silvia. "Dr. Karl Renner". Stadt Salzburg (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Bundesheer - Truppendienst - Ausgabe 1/2012 - General und Bundespräsident: Theodor Körner (1873-1957)". bundesheer.at (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Medien: Die Geschichte einer Recherche". www.profil.at (in German). 18 March 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "ÖCV - BP Dkfm. Dr. Thomas Klestil". oecv.at. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Wie wird man eigentlich Bundespräsident?". bundespraesident.at (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Artikel 60 B-VG". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Art. 60 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 60, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Wahlrechtsänderungsgesetz" (PDF). ris.bka.gv.at (in German).

- ^ "Art. 62 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 62, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Der Bundespräsident, seine Aufgaben und Rechte". bundespraesident.at (in German). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Art. 70 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 70, Fassung vom 28.09.2020" (in German). Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Kurz: 'Kickl kann nicht gegen sich selbst ermitteln'" [Kurz: 'Kickl can not investigate himself'] (in German). oe24. 19 May 2019. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ "Kurz will FPÖ-Minister durch Experten ersetzen". orf.at (in German). 20 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "Van der Bellen verweigert Goldgruber-Ernennung". sn.at (in German). 20 May 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "Art. 65 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 65, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 66 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 66, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Art. 47 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 47, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Der Weg der Bundesgesetzgebung". oesterreich.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Artikel 47 B-VG". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Art. 49 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Artikel 49 B-VG". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Art. 29 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 29, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 100 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 100, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 18 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 18, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 146 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 146, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 147 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 147, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Österreichischer Verwaltungsgerichtshof - Richer und Richterinnen". vwgh.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Art. 65 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 65, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Der Bundespräsident, seine Aufgaben und Rechte". bundespraesident.at (in German). Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Art. 80 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 80, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Ein Heer von Befehlshabern". addendum.org (in German). 30 October 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Österreichs oberster Kriegsherr". derstandard.at (in German). Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Tasks of the Austrian Armed Forces". bundesheer.at. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Wehrgesetz 2001 - WG 2001". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "Sammlung der Erkenntnisse des Verfassungsgerichthofes". alex.onb.ac.at (in German). Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Art. 63 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 63, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 60 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 60, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 142 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 142, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 68 B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 68, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 60 B-VG". jusline.at. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz Art. 60, Fassung vom 28.09.2020". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Politikergehälter: Was der österreichische Bundeskanzler verdient!". bruttonetto-rechner.at (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Wie hoch ist das Gehalt von Angela Merkel?". orange.handelsblatt.com (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Le salaire des politiques et des élus". journaldunet.com (in French). Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Salaries of Members of Her Majesty's Government from 9th June 2017" (PDF). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Politikergehälter: Was der österreichische Bundespräsident verdient!". bruttonetto-rechner.at (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Presidents' Salaries During and After Office". thebalance.com. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Räume, die Geschichte(n) schreiben". bundespraesident.at (in German). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Zwischen Amtsvilla und Dienstwohnung". diepresse.com (in German). 12 December 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Van der Bellen traf Landeshauptleute in Mürzsteg". sn.at (in German). 19 May 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "Ban Ki Moon zu Besuch bei Bundespräsident Fischer". nachrichten.at (in German). 29 August 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "§ 249 StGB Gewalt und gefährliche Drohung gegen den Bundespräsidenten". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Bundesrecht konsolidiert: Strafgesetzbuch § 249, Fassung vom 04.09.2017". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Art. 67a B-VG". jusline.at (in German). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Artikel 77 B-VG". ris.bka.gv.at (in German). Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Das Team der Präsidentschaftskanzlei". bundespraesident.at (in German). Retrieved 2 April 2020.