History of Alabama

| History of Alabama |

|---|

|

|

The history of what is now Alabama stems back thousands of years ago when it was inhabited by indigenous peoples. The Woodland period spanned from around 1000 BC to 1000 AD and was marked by the development of the Eastern Agricultural Complex.[1] This was followed by the Mississippian culture of Native Americans, which lasted to around the 1600 AD. The first Europeans to make contact with Alabama were the Spanish, with the first permanent European settlement being Mobile, established by the French in 1702.

After being a part of the Mississippi Territory (1798–1817) and then the Alabama Territory (1817–1819), Alabama would become a U.S. state on December 14, 1819. After Indian Removal forcibly displaced most Southeast tribes to west of the Mississippi River to what was then called Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), European Americans arrived in large numbers, with some of them bringing or buying African Americans in the domestic slave trade.

From the early to mid-19th century, the state's wealthy planter class considered slavery essential to their economy. As one of the largest slaveholding states, Alabama was among the first six states to secede from the Union. It declared its secession in January 1861, joining the Confederate States of America in February 1861. During the ensuing American Civil War (1861–1865) Alabama saw moderate levels of warfare and battles. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 freed all remaining enslaved people. The Southern capitulation in 1865 ended the Confederate state government, in which afterwards Alabama would transition into the Reconstruction era (1865–1877). During that time, its biracial government established the first public schools and welfare institutions in the state.

For a half century following the Civil War, Alabama was mostly economically poor and heavily rural, with few industries within the state. Agriculture production, based primarily on cotton exports, would be the state's main economic driver. Most farmers were tenants, sharecroppers or laborers who did not own land. Reconstruction ended when Democrats, calling themselves "Redeemers" regained control of the state legislature by both legal and extralegal means (including violence and harassment). In 1901, Southern Democrats in Alabama passed a state Constitution that effectively disfranchised most African Americans (who in 1900 comprised more than 45 percent of the state's population), as well as tens of thousands of Poor Whites in the state.[2][3] By 1941, a total 600,000 poor whites and 520,000 African Americans had been disfranchised.[2]

African Americans living in Alabama in the early-to-mid 20th century experienced the inequities of disfranchisement, segregation, violence and underfunded schools. Tens of thousands of African Americans from Alabama joined the Great Migration out of the South from 1915 to 1930[4] and moved for better opportunities in industrial cities, mostly in the North and Midwest. The black exodus escalated steadily in the first three decades of the 20th century; 22,100 emigrated from 1900 to 1910; 70,800 between 1910 and 1920; and 80,700 between 1920 and 1930.[5][6] As a result of African American disenfranchisement and rural white control of the legislature, state politics were dominated by Democrats, as part of the "Solid South."[7]

The Great Depression of the 1930s would hit Alabama's state economy hard. However, New Deal farm programs helped increase the price of cotton, bringing some economic relief. During and after World War II, Alabama started to see some economic prosperity, as the state developed a manufacturing and service base. In the mid-20th century cotton would fade in economic importance, with mechanization technologies, the reduced need for farm labor, as well as their now being new job opportunities in different industries. Following years of struggles, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolished segregation, along with African Americans being able to again exercise their constitutional right to vote.

In the mid-to-late 20th century, the formation of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, would help the states economic growth by developing an aerospace industry. In 1986, the election of Guy Hunt as governor marked a shift in Alabama toward becoming a Republican stronghold in Presidential elections as its voters also leaned Republican in statewide elections. The Democratic Party still dominated many local and legislative offices, but total Democrat dominance had ended.[8] In the early 21st century, Alabama's economy was fueled in part by aerospace, agriculture, auto production, and the service sector.[9]

Indigenous peoples, early history

[edit]Precontact

[edit]

At least 12,000 years ago, Native Americans or Paleo-Indians appeared in what is today referred to as "The South".[10] Paleo-Indians in the Southeast were hunter-gatherers who pursued a wide range of animals, including the megafauna, which became extinct following the end of the Pleistocene age. Their diets were based primarily on plants, gathered and processed by women who learned about nuts, berries and other fruits, and the roots of many plants.[10] The Woodland period from 1000 BCE to 1000 CE was marked by the development of pottery and the small-scale horticulture of the Eastern Agricultural Complex.

The Mississippian culture arose as the cultivation of Mesoamerican crops of corn and beans led to crop surpluses and population growth. Increased population density gave rise of urban centers and regional chiefdoms, of which the greatest was the city known as Cahokia, in present-day Illinois near the confluence of the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. The culture spread along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and their tributaries. Its population of 20,000 to 30,000 at its peak exceeded that of any of the later European cities in North America until 1800. Stratified societies developed, with hereditary religious and political elites, and flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from 800 to 1500 C.E.

Trade with the Northeast indigenous peoples via the Ohio River began during the Burial Mound Period (1000 BC–AD 700) and continued until European contact.[11] The agrarian Mississippian culture covered most of the state from 1000 to 1600 AD, with one of its major centers being at the Moundville Archaeological Site in Moundville, Alabama, the second-largest complex of this period in the United States. Some 29 earthwork mounds survive at this site.[12][13]

Analysis of artifacts recovered from archaeological excavations at Moundville were the basis of scholars' formulating the characteristics of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC).[14] Contrary to popular belief, the SECC appears to have no direct links to Mesoamerican culture, but developed independently. The Ceremonial Complex represents a major component of the religion of the Mississippian peoples; it is one of the primary means by which their religion is understood.[15]

The early historic Muscogee are considered likely descendants of the Mississippian culture along the Tennessee River in modern Tennessee,[16] Georgia and Alabama. They may have been related to the Utinahica of southern Georgia. At the time the Spanish made their first forays inland from the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, many political centers of the Mississippians were already in decline, or abandoned.[17]

Among the historical tribes of Native American people living in the area of present-day Alabama at the time of European contact were the Muskogean-speaking Alabama (Alibamu), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Koasati, and Mobile peoples. Also in the region were the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee, from a different family and cultural group. They are believed to have migrated south at an earlier time from the Great Lakes area, based on their language's similarity to those of the Iroquois Confederacy and other Iroquoian-speaking tribes around the Great Lakes.[18] The history of Alabama's Native American peoples is reflected in many of its place names.

European colonization

[edit]

The Spanish were the first Europeans to enter Alabama, claiming land for their Crown. They named the region as La Florida, which extended to the southeast peninsular state now bearing the name.

Although a member of Pánfilo de Narváez's expedition of 1528 may have entered southern Alabama, the first fully documented visit was by explorer Hernando de Soto. In 1539 he made an arduous expedition along the Coosa, Alabama and Tombigbee rivers.

The Alabama region at the period of European contact is best described as a collection of moderately sized native chiefdoms (such as the Coosa chiefdom on the upper Coosa River and the Tuskaloosa chiefdom on the lower Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Alabama Rivers), interspersed with completely autonomous villages and tribal groups. Many of the settlements de Soto encountered had platform mounds and villages fortified with defensive palisades with bastions for archers. The South Appalachian Mississippian culture Big Eddy phase has been tentatively identified as the protohistoric Province of Tuskaloosa encountered by the de Soto expedition in 1540. The Big Eddy phase Taskigi Mound is a platform mound and fortified village site located at the confluence of the Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Alabama Rivers near Wetumpka, Alabama. It is preserved as part of the Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson State Historic Site and is one of the locations included on the University of Alabama Museums "Alabama Indigenous Mound Trail".[19][20]

The English also laid claims to the region north of the Gulf of Mexico. Charles II of England included most of the territory of modern Alabama in the Province of Carolina, with land granted to certain of his favorites by the charters of 1663 and 1665. English traders from Carolina frequented the valley of the Alabama River as early as 1687 to trade for deerskins with the Native American peoples.

The French also colonized the region. In 1702 they founded a settlement on the Mobile River near its mouth, constructing Fort Louis. For the next nine years this was the French seat of government of New France, or La Louisiane (Louisiana). In 1711, they abandoned Fort Louis because of repeated flooding. Settlers rebuilt a fort on higher ground known as Fort Conde. This was the start of what developed as present-day Mobile, the first permanent European settlement in Alabama. Biloxi was another early French settlement on the Gulf Coast, to the west in what is now Mississippi.

The French and the English contested the region, each attempting to forge strong alliances with Indian tribes. To strengthen their position, defend their Indian allies, and draw other tribes to them, the French established the military posts of Fort Toulouse, near the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers, and Fort Tombecbe on the Tombigbee River.

The French and the English engaged in competition for Indian trade in what is now the state of Alabama between roughly the 1690s and the 1750s, at which point the French and Indian War broke out. It was the North American front of the Seven Years' War between these two nations in Europe. Though the French claimed the territory as their own and attempted to rule it from Fort Toulouse, so as to engage in trade with the Indians, English traders based out of the Carolinas infiltrated the region, also engaging in trade. The Chickasaw frequently favored the English in this contest. [citation needed]

Overall, during this time the English proved to be the better traders and colonizers. They operated independently, while the French government was more directly involved in its colonies. On this note Edmund Burke would later note that English colonists in America would owe their freedom more "to [the Crown's] carelessness than to its design". This was a policy referred to as "salutary neglect". The distance between the colonies and the home countries meant they could always operate with some freedom.[21][citation needed]

The English Crown's grant of Georgia to Oglethorpe and his associates in 1732 included a portion of what is now northern Alabama. In 1739, Oglethorpe visited the Creek Indians west of the Chattahoochee River and made a treaty with them.

The 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Seven Years' War after France's defeat by Britain, resulted in France ceding its territories east of the Mississippi to Britain. Great Britain came into undisputed control of the region between the Chattahoochee and the Mississippi rivers, in terms of other European powers. Of course it had not consulted with any of the numerous indigenous peoples whom it nominally "ruled." The portion of Alabama below the 31st parallel was considered a part of British West Florida. The British Crown defined the portion north of this line as part of the "Illinois Country"; the area west of the Appalachian Mountains was to be reserved for use by Native American tribes. European-American settlers were not supposed to encroach in that territory, but they soon did. In 1767, Britain expanded the province of West Florida northward to 32°28'N latitude.

More than a decade later, during the American Revolutionary War, the British informally ceded this West Florida region to Spain. By the Treaty of Versailles, September 3, 1783, Great Britain formally ceded West Florida to Spain. By the Treaty of Paris (1783), signed the same day, Britain ceded to the newly established United States all of this province north of 31°N, thus laying the foundation for a long controversy.

By the Treaty of Madrid in 1795, Spain ceded to the United States the lands east of the Mississippi between 31°N and 32°28'N. Three years later, in 1798, Congress organized this district as the Mississippi Territory. A strip of land 12 or 14 miles wide near the present northern boundary of Alabama and Mississippi was claimed by South Carolina, as part of the eastern colonies' previous hopeful extensions to the west. In 1787, during constitutional negotiations, South Carolina ceded this claim to the federal government. Georgia likewise claimed all the lands between the 31st and 35th parallels from its present western boundary to the Mississippi River, and did not surrender its claim until 1802. Two years later, the boundaries of Mississippi Territory were extended so as to include all of the Georgia cession.

In 1812, Congress added the Mobile District of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory, claiming that it was included in the Louisiana Purchase. The following year, General James Wilkinson occupied the Mobile District with a military force. The Spanish did not resist. Thus the whole area of the present state of Alabama was taken under the jurisdiction of the United States. Several powerful Native American tribes still occupied most of the land, with some formal ownership recognized by treaty with the United States. Five of the major tribes became known as the Five Civilized Tribes, as they had highly complex cultures and adopted some elements of European-American culture.

In 1817, the Mississippi Territory was divided. The western portion, which had attracted population more quickly, became the state of Mississippi. The eastern portion became the Alabama Territory, with St. Stephens on the Tombigbee River as its temporary seat of government.

Conflict between the various tribes in Alabama and American settlers increased rapidly in the early 19th century because the Americans kept encroaching on Native American territories. The great Shawnee chief Tecumseh visited the region in 1811, seeking to forge an Indian alliance among these tribes to join his resistance in the Great Lakes area. With the outbreak of the War of 1812, Britain encouraged Tecumseh's resistance movement, in the hope of expelling American settlers from west of the Appalachians. Several tribes were divided in opinion.

The Creek tribe fell to civil war (1813–1814). Violence between Creeks and Americans escalated, culminating in the Fort Mims massacre. Full-scale war between the United States and the "Red Stick" Creeks began; they were the more traditional members of their society who resisted US encroachment. The Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee Nation and other Creek factions remained neutral to or allied with the United States during the war; they were highly decentralized in bands' alliances. Some warriors from among the bands served with American troops. Volunteer militias from Georgia, South Carolina and Tennessee marched into Alabama, fighting the Red Sticks.

Later, federal troops became the main fighting force for the United States. General Andrew Jackson was the commander of the American forces during the Creek War and in the continuing effort against the British in the War of 1812. His leadership and military success during the wars made him a national hero. The Treaty of Fort Jackson (August 9, 1814) ended the Creek War. By the terms of the treaty, the Creek, Red Sticks and neutrals alike, ceded about one-half of the present state of Alabama to the United States. Due to later cessions by the Cherokee, Chickasaw and Choctaw in 1816, they retained only about one-quarter of their former territories in Alabama.

Early statehood

[edit]In 1819, Alabama was admitted as the 22nd state to the Union. Its constitution provided for equal suffrage for white men, a standard it abandoned in its constitution of 1901, which reduced suffrage of poor whites and most blacks, disenfranchising tens of thousands of voters.[22]

One of the first problems of the new state was finance. Since the amount of money in circulation was not sufficient to meet the demands of the increasing population, a system of state banks was instituted. State bonds were issued and public lands were sold to secure capital, and the notes of the banks, loaned on security, became a medium of exchange. Prospects of an income from the banks led the legislature of 1836 to abolish all taxation for state purposes. The Panic of 1837 wiped out a large portion of the banks' assets, leaving the state poor. Next came revelations of grossly careless and corrupt management. In 1843 the banks were placed in liquidation. After disposing of all their available assets, the state assumed the remaining liabilities, for which it had pledged its faith and credit.[23]

In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act under the leadership of President Andrew Jackson, authorizing federal removal of southeastern tribes to west of the Mississippi River, including the Five Civilized Tribes of Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole (in Florida). In 1832, the national government provided for the removal of the Creek via the Treaty of Cusseta. Before the removal occurred between 1834 and 1837, the state legislature organized counties in the lands to be ceded, and European-American settlers flocked in before the Native Americans had left.[24]

Until 1832, the Democratic-Republican Party was the only one in the state, descended from the time of Jefferson. Disagreements over whether a state could nullify a federal law caused a division within the Democratic party. About the same time the Whig party emerged as an opposition party. It drew support from planters and townsmen, while the Democrats were strongest among poor farmers and Catholic communities (descendants of French and Spanish colonists) in the Mobile area. For some time, the Whigs were almost as numerous as the Democrats, but they never secured control of the state government. The States' Rights faction were in a minority; nevertheless, under their persistent leader, William L. Yancey (1814–1863), they prevailed upon the Democrats in 1848 to adopt their most radical views.[25]

During the agitation over the Wilmot Proviso, which would bar slavery from territory acquired from Mexico as a result of the Mexican War (1848), Yancey induced the Democratic State Convention of 1848 to adopt what was known as the "Alabama Platform". It declared that neither Congress nor the government of a territory had the right to interfere with slavery in a territory, that those who held opposite views were not Democrats, and that the Democrats of Alabama would not support a candidate for the presidency if he did not agree with them. This platform was endorsed by conventions in Florida and Virginia and by the legislatures of Georgia and Alabama.

In antebellum Alabama, wealthy planters created large cotton plantations based in the fertile central Black Belt of the upland region, which depended on the labor of enslaved Africans. Tens of thousands of slaves were transported to and sold in the state by slave traders who purchased them in the Upper South. In the mountains and foothills, poorer whites practiced subsistence farming. By 1860 blacks (nearly all slaves) comprised 45 percent of the state's 964,201 people.

Tensions related to slavery divided many state delegations in Congress, as this body tried to determine the futures of territories beyond the Mississippi River. Following the Congressional passage of the Compromise of 1850, which assigned certain territories as slave or free, in Alabama people began to realign politically. The States' Rights faction, joined by many Democrats, founded the Southern Rights Party, which demanded the repeal of the Compromise, advocated resistance to future encroachments, and prepared for secession. The Whigs were joined by the remaining Democrats and called themselves the "Unionists". The party unwillingly accepted the Compromise and denied that the Constitution provided for secession.

Since the turn of the 19th century, development of large cotton plantations had taken place across the upland Black Belt after the invention of the cotton gin made short-staple cotton profitable. Cotton had added dramatically to the state's wealth. The owners' wealth depended on the labor of hundreds of thousands of enslaved African Americans, many initially transported in the domestic trade from the Upper South, which resulted in one million workers being relocated to the South. In other parts of the state, the soil supported only subsistence farming. Most of the yeoman farmers owned few or no slaves. By 1860 the investment and profits in cotton production resulted in planters holding 435,000 enslaved African Americans, who made up 45% of the state's population.

At the time of statehood, the early Alabama settlers adopted universal white suffrage. They were noted for a spirit of frontier democracy and egalitarianism, but this declined after the slave society developed.[26] J. Mills Thornton argues that Whigs worked for positive state action to benefit society as a whole, while the Democrats feared any increase of power in government or in state-sponsored institutions as central banks. Fierce political battles raged in Alabama on issues ranging from banking to the removal of the Creek Indians. Thornton suggested the overarching issue in the state was how to protect liberty and equality for white people. Fears that Northern agitators threatened their value system and slavery as the basis of their wealthy economy made voters ready to secede when Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860.[27]

Secession and Civil War (1861–1865)

[edit]The "Unionists" were successful in the elections of 1851 and 1852. Passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill and uncertainty about agitation against slavery led the State Democratic convention of 1856 to revive the "Alabama Platform". When the Democratic National Convention at Charleston, South Carolina, failed to approve the "Alabama Platform" in 1860, the Alabama delegates, followed by those of the other "cotton states", withdrew. Upon the election of Abraham Lincoln, Governor Andrew B. Moore, as previously instructed by the legislature, called a state convention. Many prominent men had opposed Alabama secession. In North Alabama, there was an attempt to organize a neutral state to be called Nickajack. With President Lincoln's call to arms in April 1861, most opposition to secession ended.

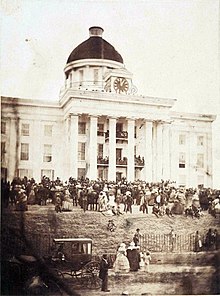

On January 11, 1861, the State of Alabama adopted the ordinances of secession[28] from the Union (by a vote of 61–39). Alabama joined the Confederate States of America, whose government was first organized at Montgomery on February 4, 1861. The CSA set up its temporary capital in Montgomery and selected Jefferson Davis as president. In May 1861, the Confederate government abandoned Montgomery before the sickly season began and relocated to Richmond, Virginia, the capital of that state. During the ensuing American Civil War Alabama had moderate levels of warfare.

Governor Moore energetically supported the Confederate war effort. Even before hostilities began, he seized Federal facilities, sent agents to buy rifles in the Northeast and scoured the state for weapons. Despite some resistance in the northern part of the state, Alabama joined the Confederate States of America (CSA). Congressman Williamson R. W. Cobb was a Unionist and pleaded for compromise. When he ran for the Confederate congress in 1861, he was defeated. (In 1863, with war-weariness growing in Alabama, he was elected on a wave of antiwar sentiment.)

Some idea of the current transportation patterns and severe internal logistic problems faced by the Confederacy can be seen by tracing Jefferson Davis' journey from his plantation in Mississippi to Montgomery. With few roads and railroads, he traveled by steamboat from his plantation on the Mississippi River down to Vicksburg, where he boarded a train to Jackson, Mississippi. He took another train north to Grand Junction, then a third train east to Chattanooga, Tennessee and a fourth train south to the main hub at Atlanta, Georgia. He took another train to the Alabama border and a last one to Montgomery in the center of the state.

As the war proceeded, the Federals seized ports along the Mississippi River, burned trestles and railroad bridges and tore up track. The frail Confederate railroad system faltered and virtually collapsed for want of repairs and replacement parts.

In the early part of the Civil War, Alabama was not the scene of military operations. The state contributed about 120,000 soldiers to Confederate service. Most soldiers were recruited locally and served with others they knew, which built esprit and strengthened ties to home. Medical conditions were severe for all soldiers. About 15% of deaths were from disease, more than the 10% from battle. Alabama had few well-equipped hospitals, but it had many on the home front who volunteered to nurse the sick and wounded. Soldiers were poorly equipped, especially after 1863. Often they pillaged the dead for boots, belts, canteens, blankets, hats, shirts and pants.

Uncounted thousands of slaves were impressed to work for Confederate troops; they took care of horses and equipment, cooked and did laundry, hauled supplies, and helped in field hospitals. Other slaves built defensive installations, especially those around Mobile. They graded roads, repaired railroads, drove supply wagons, and labored in iron mines, iron foundries and even in the munitions factories. The service of slaves was involuntary: their unpaid labor was impressed from their unpaid masters. About 10,000 slaves within the state escaped and joined the Union army.

Around 2,700 white men from Alabama who were adherent Southern Unionists served in the Union Army, many of whom served in the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment.

Thirty-nine Alabamians attained flag rank, most notably Lieutenant General James Longstreet and Admiral Raphael Semmes. Josiah Gorgas, who came to Alabama from Pennsylvania, was the chief of ordnance for the Confederacy. He located new munitions plants in Selma, which employed 10,000 workers until the Union soldiers burned the factories down in 1865. Selma Arsenal made most of the Confederacy's ammunition. The Selma Naval Ordnance Works made artillery, turning out a cannon every five days. The Confederate Naval Yard built ships and was noted for launching the CSS Tennessee in 1863 to defend Mobile Bay. Selma's Confederate Nitre Works procured niter for the Nitre and Mining Bureau for gunpowder, from limestone caves. When supplies were low, it advertised for housewives to save the contents of their chamber pots—as urine was a rich source of nitrogen.

In 1863, Union forces secured a foothold in northern Alabama in spite of the opposition of General Nathan B. Forrest. From 1861, the Union blockade shut Mobile, and, in 1864, the outer defenses of Mobile were taken by a Union fleet; the city itself held out until April 1865.[29]

Alabama soldiers fought in hundreds of battles; the state's losses at the Battle of Gettysburg were the highest loss of any battle with 1,750 dead plus more captured or wounded; the "Alabama Brigade" took 781 casualties. Governor Lewis E. Parsons in July 1865 made a preliminary estimate of losses, which totaled that around the 122,000 Alabamian soldiers who served, around 35,000 died during the war. The next year Governor Robert M. Patton estimated that 20,000 veterans had returned home with permanent disabilities. With cotton prices low, the value of farms shrank, from $176 million in 1860 to only $64 million in 1870. The livestock supply shrank too, as the number of horses fell from 127,000 to 80,000, and mules from 111,000 to 76,000. The overall population growth remained the same, the growth that might have been expected was neutralized by death and emigration out of the state.[30]

Reconstruction (1865–1875)

[edit]According to the Presidential plan of reorganization, a provisional governor for Alabama was appointed in June 1865. A state convention met in September of the same year, and declared the ordinance of secession null and void and slavery abolished. A legislature and a governor were elected in November, and the legislature was at once recognized by President Andrew Johnson, but not by Congress, which refused to seat the delegation. Johnson ordered the army to allow the inauguration of the governor after the legislature ratified the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865. But the legislature's passage of Black Codes to control the freedmen who were flocking from the plantations to the towns, and its rejection of the Fourteenth Amendment to grant suffrage, intensified Congressional hostility to the Presidential plan.

In 1867, the congressional plan of Reconstruction was completed and Alabama was placed under military government. The freedmen were enrolled as voters. Only whites who could swear the Ironclad oath could be voters; that is they had to swear they had never voluntarily supported the Confederacy. This provision was insisted upon by the whites in the northern hill counties so they could control local government. As a result, Republicans controlled 96 of the 100 seats in the state constitutional convention.[31] The new Republican party, made up of freedmen, southern white Union sympathizers (scalawags), and northerners who had settled in the South (carpetbaggers), took control two years after the war ended. The constitutional convention in November 1867 framed a constitution which conferred universal manhood suffrage and imposed the iron-clad oath, so that whites who had supported the Confederacy were temporarily prohibited from holding office. The Reconstruction Acts of Congress required every new constitution to be ratified by a majority of the legal voters of the state. Most whites boycotted the polls and the new constitution fell short. Congress enacted that a majority of the votes cast should be sufficient. Thus the constitution went into effect, the state was readmitted to the Union in June 1868, and a new governor and legislature were elected.

Many whites resisted postwar changes, complaining that the Republican governments were notable for legislative extravagance and corruption. But the Republican biracial coalition created the first system of public education in the state, which would benefit poor white children as well as freedmen. They also created charitable public institutions, such as hospitals and orphanages, to benefit all citizens. The planters had not made public investment but kept their wealth for themselves. As the state tried to improve institutions and infrastructure for the future, the state debt and state taxes rose. The state endorsed railway bonds at the rate of $12,000 and $16,000 a mile until the state debt had increased from eight million to seventeen million dollars. The native whites united, peeling many Alabama Scalawags away from the Republican coalition, and elected a governor and a majority of the lower house of the legislature in 1870, in an election characterized by widespread violence and fraud. As the new administration was overall a failure, in 1872, voters re-elected Republicans.

By 1874, however, the power of the Republicans was broken, and Democrats regained power in all state offices. A commission appointed to examine the state debt found it to be $25,503,000; by compromise, it was reduced to $15,000,000. A new constitution was adopted in 1875, which omitted the guarantee of the previous constitution that no one should be denied suffrage on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude. Its provisions forbade the state to engage in internal improvements or to give its credit to any private enterprise, an anti-industrial stance that persisted and limited the state's progress for decades into the 20th century.[32]

In the South, the interpretation of the tumultuous 1860s has differed sharply by race. Americans often interpreted great events in religious terms. Historian Wilson Fallin contrasts the interpretation of Civil War and Reconstruction in white versus black using Baptist sermons in Alabama. White preachers expressed the view that:

- God had chastised them and given them a special mission – to maintain orthodoxy, strict biblicism, personal piety and traditional race relations. Slavery, they insisted, had not been sinful. Rather, emancipation was a historical tragedy, and the end of Reconstruction was a clear sign of God's favor.

In sharp contrast, black preachers interpreted the Civil War, emancipation and Reconstruction as:

- God's gift of freedom. They appreciated opportunities to exercise their independence, to worship in their own way, to affirm their worth and dignity and to proclaim the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. Most of all, they could form their own churches, associations and conventions. These institutions offered self-help, racial uplift and provided places where the gospel of liberation could be proclaimed. As a result, black preachers continued to insist that God would protect and help them: God would be their rock in a stormy land.[33]

Democratic politics and disfranchisement

[edit]After 1874, the Democratic party had constant control of the state administration. The Republican Party by then was chiefly supported by African Americans. Republicans held no local or state offices, but the party did have some federal patronage. It failed to make nominations for office in 1878 and 1880 and endorsed the ticket of the Greenback party in 1882.[34][35]

The development of mining and manufacturing was accompanied by economic distress among the farming classes, which found expression in the Jeffersonian Democratic party, organized in 1892. The regular Democratic ticket was elected and the new party was merged into the Populist party. In 1894, the Republicans united with the Populists, elected three congressional representatives, and secured control of many of the counties. They did not succeed in carrying the state. The Populist coalition had less success in the next campaigns. Partisanship became intense, and Democratic charges of corruption of the black electorate were matched by Republican and Populist accusations of fraud and violence by Democrats.[36]

Despite opposition by Republicans and Populists, Democrats completed their dominance with passage of a new constitution in 1901 that restricted suffrage and effectively disenfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites, through requirements for voter registration, such as poll taxes, literacy tests and restrictive residency requirements. From 1900 to 1903, the number of white registered voters fell by more than 40,000, from 232,821 to 191,492, despite a growth in population. By 1941 a total of more whites than blacks had been disenfranchised: 600,000 whites to 520,000 blacks. This was due mostly to effects of the cumulative poll tax.[37]

The damage to the African-American community was severe and pervasive, as nearly all its eligible citizens lost the ability to vote. In 1900 45% of Alabama's population were African American: 827,545 citizens.[38] In 1900 fourteen Black Belt counties (which were primarily African American) had more than 79,000 voters on the rolls. By June 1, 1903, the number of registered voters had dropped to 1,081. While Dallas and Lowndes counties were each 75% black, between them only 103 African-American voters managed to register. In 1900 Alabama had more than 181,000 African Americans eligible to vote. By 1903 only 2,980 had managed to "qualify" to register, although at least 74,000 black voters were literate. The shut out was long-lasting. The effects of segregation suffered by African Americans were severe. At the end of WWII, for instance, in the black Collegeville community of Birmingham, only eleven voters in a population of 8,000 African Americans were deemed "eligible" to register to vote.[2] Disfranchisement also meant that blacks and poor whites could not serve on juries, so were subject to a justice system in which they had no part.

Progressive era (1900–1930)

[edit]

The Progressive Movement in Alabama, while not as colorful or successful as in some other states, drew upon the energies of a rapidly growing middle class, and flourished from 1900 to the late 1920s.[39] Reforms that were enacted included the corrupt practices act of 1915; the registration law of 1915; the direct election of U.S. senators; encouraging the establishment of commission government in the towns and cities; and the ratification of the 19th amendment to allow women the right to vote. They replaced nomination by party convention with primary elections for nominating candidates. While the Progressives denied Blacks and many poor white people the right to vote, they did facilitate much more opportunity for participation in the government to middle class whites.[40]

B. B. Comer (1848–1927) was the state's most prominent progressive leader, especially during his term as governor (1907–1911). Middle-class reformers placed high on their agenda the regulation of railroads, and a better school system, with compulsory education and the prohibition of child labor.[41] Comer sought 20 different railroad laws, to strengthen the railroad commission, reduce free passes handed out to grasping politicians, lobbying, and secret rebates to favored shippers. The Legislature approved his package, except for a provision that tried to forbid freight trains operating on Sundays. The result was a reduction in both freight and passenger rates. Railroads fought back vigorously in court, and in the arena of public opinion. The issue was fiercely debated for years, making Alabama laggard among the southern states in terms of controlling railroad rates. Finally in 1914 a compromise was reached, in which the railroads accepted the reduced passenger rates, but were free to seek higher freight rates through the court system.[42][43]

Progressive reforms cost money, especially for the improved school system. Eliminating the inefficiencies of the tax collection system helped a bit. Reformers wanted to end the convict lease system, but it was producing a profit to the government of several hundred thousand dollars a year. That was too lucrative to abolish; however the progressives did move control over convict lease from the counties to a statewide system. Finally the legislature increased statewide funding for the schools, and established the policy of at least one high school in every county; by 1911 half the counties operated public high schools for whites. Compulsory education was opposed by working-class families who wanted their children to earn money, and who distrusted the schooling the middle class was so insistent upon. But it finally passed in 1915; it was enforced for whites only and did not apply to farms. By 1910 Alabama still lagged with 62 percent of its children in school, compared to a national average of 71 percent.

The progressives worked hard to upgrade the hospital and public health system, with provisions to require the registration of births and deaths to provide the information needed. When the Rockefeller Foundation identified the hookworm as a critical element in draining energy out of Southern workers, Alabama discovered hookworm cases in every county, with rates as high as 60 percent. The progressive genius for organization and devotion to the public good was least controversial in the public health area and probably most successful there.[44] Prohibition was a favorite reform for Protestant churches across this entire country, and from the 1870s to the 1920s, Alabama passed a series of more restrictive laws that were demanded by the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and other reform elements.[45][46]

Middle-class business and professional activists in the cities were frustrated with the old-fashioned politicized city governments and demanded a commission formed in which municipal affairs would be very largely run by experts rather than politicians. Emmet O'Neal, elected governor in 1910, made the commission system his favored reform, and secured its passage by the legislature in 1911. The cities of Birmingham, Montgomery and Mobile quickly adopted the commission form[47]

Women energized by the prohibition wars turned their crusading energies to woman suffrage. They were unable to overcome male supremacy until the national movement passed the 19th amendment, granting women the right to vote in 1920.[48]

Railroads and industry

[edit]The economy of Alabama in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was largely based on agriculture and industry. Cotton was the primary crop grown in the state, and it was supplemented by corn and livestock. Timber was also an important part of the economy, as large tracts of pine forests were harvested for lumber and naval stores such as turpentine and rosin. Iron ore was mined from the Appalachian Mountains and shipped to the state's steel mills. By the 1880s, Alabama was a major producer of coal, and the state's railroads helped to transport the coal to other markets. Manufacturing also began to take hold in the state, with the establishment of cotton mills, sawmills, and other industries.[49]

By the 1920s, the urban economy was largely based on manufacturing, with the production of cotton textiles, timber products, and iron and steel being the major industries. The Great Depression of the 1930s, however, caused a significant decline in the state's economy[49]

Birmingham was founded on June 1, 1871, by real estate promoters who sold lots near the planned crossing of the Alabama & Chattanooga and South & North railroads. The site was notable for the nearby deposits of iron ore, coal and limestone—the three principal raw materials used in making steel. Its founders adopted the name of England's principal industrial city to advertise the new city as a center of iron and steel production. Despite outbreaks of cholera, the population of this 'Pittsburgh of the South' grew from 38,000 to 132,000 from 1900 to 1910, attracting rural white and black migrants from all over the region.[50] Birmingham experienced such rapid growth that it was nicknamed "The Magic City." By the 1920s, Birmingham was the 19th largest city in the U.S. and held more than 30% of the population of the state. Heavy industry and mining were the basis of the economy. Chemical and structural constraints limited the quality of steel produced from Alabama's iron and coal. These materials did, however, combine to make ideal foundry iron. Because of low transportation and labor costs, Birmingham quickly became the largest and cheapest foundry iron-producing area. By 1915, twenty-five percent of the nation's foundry pig iron was produced in Birmingham.[51][52]

New South era beginnings (1914–1945)

[edit]Despite Birmingham's powerful industrial growth and its contributions to the state economy, its citizens, and those of other newly developing areas, were underrepresented in the state legislature for years. The rural-dominated legislature refused to redistrict state House and Senate seats from 1901 to the 1960s. In addition, the state legislature had a senate based on one for each county. The state legislative delegations controlled counties. This led to a stranglehold on the state by a white rural minority. The contemporary interests of urbanizing, industrial cities and tens of thousands of citizens were not adequately represented in the government.[53] One result was that Jefferson County, home of Birmingham's industrial and economic powerhouse, contributed more than one-third of all tax revenue to the state. It received back only 1/67th of the tax money, as the state legislature ensured taxes were distributed equally to each county regardless of population.

From 1910 to 1940, tens of thousands of African Americans migrated out of Alabama in the Great Migration to seek jobs, education for their children, and freedom from lynching in northern and midwestern cities, such as St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. These cities had many industrial jobs, but the migrants also had to compete with new waves of European immigrants. The rate of population growth in Alabama dropped from 20.8% in 1900 and 16.9% in 1910, to 9.8% in 1920, reflecting the impact of the outmigration. Formal disenfranchisement was ended only after the mid-1960s after African Americans led the Civil Rights Movement and gaining Federal legislation to protect their voting and civil rights. But the state devised new ways to reduce their political power. By that time, African Americans comprised a smaller minority than at the turn of the century, and a majority in certain rural counties.

A rapid pace of change across the country, especially in growing cities, combined with new waves of immigration and migration of rural whites and blacks to cities, all contributed to a volatile social environment and the rise of a second Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the South and Midwest after 1915. In many areas it represented itself as a fraternal group to give aid to a community. Feldman (1999) has shown that the second KKK was not a mere hate group; it showed a genuine desire for political and social reform on behalf of poor whites. For example, Alabama Klansmen such as Hugo Black were among the foremost advocates of better public schools, effective Prohibition enforcement, expanded road construction, and other "progressive" measures to benefit poor whites. By 1925, the Klan was a powerful political force in the state, as urban politicians such as J. Thomas Heflin, David Bibb Graves, and Hugo Black manipulated the KKK membership against the power of the "Big Mule" industrialists and especially the Black Belt planters who had long dominated the state.[54]

In 1926, Democrat Bibb Graves, a former chapter head, won the governor's office with KKK members' support. He led one of the most progressive administrations in the state's history, pushing for increased education funding, better public health, new highway construction, and pro-labor legislation. At the same time, KKK vigilantes—thinking they enjoyed governmental protection—launched a wave of physical terror across Alabama in 1927, targeting both blacks and whites. The Republicans responded: The major newspapers kept up a steady, loud attack on the Klan as violent and un-American. Sheriffs cracked down on Klan violence, and a national scandal among Klan leaders in the 1920s turned many members away. The state voted for Democrat Al Smith in 1928, although he was Roman Catholic (a target of the KKK). The Klan's official membership plunged to under six thousand by 1930.

World War II

[edit]Alabama was an important player in the United States home front during World War II. The state provided thousands of soldiers, sailors and airmen to the military. It provided large amounts of food, ammunition, and other supplies. Alabama was also the site of numerous military bases and factories that produced military supplies and equipment and warships. In addition, the state was home to several prisoner of war camps and Army and Navy hospitals. The iron and steel industries in Birmingham smoothly transitioned to wartime production, with furnaces that had closed during the Great Depression reopening to meet the demands of War Production Board contracts. Alabama's Ingalls Iron Works became a leader in the construction of Liberty ships, launching the first fully welded ship in October 1940, helping revolutionize the ship building industry.[55][56]

On February 12, 1945, a devastating tornado outbreak occurred across the Southeastern United States, which killed 45 people and injured 427 others.[57][58] This outbreak included a devastating tornado that struck Montgomery, Alabama, which killed 26 people.[58] The United States Weather Bureau described this tornado as "the most officially observed one in history" as it reached within 0.5 miles (0.80 km) from the U.S. Weather Bureau's office.[58] Tornado expert Thomas P. Grazulis estimated the intensity of the Montgomery tornado to be F3 on the Fujita scale.[57]

Civil Rights Movement and redistricting (1945–1975)

[edit]Economically, the major force in Alabama was the mechanization and consolidation of agriculture. Mechanical cotton pickers became available in the postwar era, reducing the need for many agricultural workers. They tended to move into the region's urban areas. Still, by 1963, only about a third of the state's cotton was picked by machine.[59] Diversification from cotton into soybeans, poultry and dairy products also drove more poor people off the land.[60] In the state's thirty-five Appalachian counties, twenty-one lost population between 1950 and 1960. What was once a rural state became more industrial and urban.[61]

Following service in World War II, many African-American veterans became activists for civil rights, wanting their rights under the law as citizens. The Montgomery bus boycott from 1955 to 1956 was one of the most significant African-American protests against the policy of racial segregation in the state. Although constituting a majority of bus passengers, African Americans were discriminated against in seating policy. The protest nearly brought the city bus system to bankruptcy and changes were negotiated. The legal challenge was settled in Browder v. Gayle (1956), a case in which the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama found the segregation policy to be unconstitutional under Fourteenth Amendment provisions for equal treatment; it ordered that public transit in Alabama be desegregated.

The rural white minority's hold on the legislature continued, however, suppressing attempts by more progressive elements to modernize the state. A study in 1960 concluded that because of rural domination, "A minority of about 25 per cent of the total state population is in majority control of the Alabama legislature."[53] Given the legislature's control of the county governments, the rural interests had even more power. Legislators and others filed suit in the 1960s to secure redistricting and reapportionment. It took years and Federal court intervention to achieve the redistricting necessary to establishing "one man, one vote" representation, as a result of Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964). The court ruled that, in addition to the states having to redistrict to reflect decennial censuses in congressional districts, both houses of state governments had to be based on representation by population districts, rather than by geographic county as the state senate had been, as the senate's make-up prevented equal representation. These court decisions caused redistricting in many northern and western states as well as the South, where often rural interests had long dominated state legislatures and prevented reform.

In 1960 on the eve of important civil rights battles, 30% of Alabama's population was African American or 980,000.[62]

As Birmingham was the center of industry and population in Alabama, in 1963 civil rights leaders chose to mount a campaign there for desegregation. Schools, restaurants and department stores were segregated; no African Americans were hired to work in the stores where they shopped or in the city government supported in part by their taxes. There were no African-American members of the police force. Despite segregation, African Americans had been advancing economically. But from 1947 to 1965, Birmingham suffered "about 50 racially motivated bomb attacks."[63] Independent groups affiliated with the KKK bombed transitional residential neighborhoods to discourage blacks' moving into them; in 19 cases, they bombed black churches with congregations active in civil rights, and the homes of their ministers.[63])

To help with the campaign and secure national attention, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth invited members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to Birmingham to help change its leadership's policies, as non-violent action had produced good results in some other cities. The Reverends Martin Luther King Jr. and Wyatt Tee Walker, SCLC's president and executive director, respectively, joined other civil rights movement leaders who travelled to Birmingham to help.

In the spring and summer of 1963, national attention became riveted on Birmingham. The media covered the series of peaceful marches that the Birmingham police, headed by Police Commissioner Bull Connor, attempted to divert and control. He invited high school students to join the marches, as King intended to fill the jails with nonviolent protesters to make a moral argument to the United States. Dramatic images of Birmingham police using police dogs and powerful streams of water against children protesters filled newspapers and television coverage, arousing national outrage. The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing during a Sunday service, which killed four African-American girls, caused a national outcry and gained support for the civil rights cause in the state. 16th Street Baptist Church had been a rallying point and staging area for civil rights activities in Birmingham prior to the bombing. Finally, Birmingham leaders King and Shuttlesworth agreed to end the marches when the businessmen's group committed to end segregation in stores and public facilities.

Before his November 1963 assassination, President John F. Kennedy had supported civil rights legislation. In 1964 President Lyndon B. Johnson helped secure its passage and signed the Civil Rights Act. The Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965 attracted national and international press and TV coverage. The nation was horrified to see peaceful protesters beaten as they entered the county. That year, Johnson helped achieve passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act to gain federal oversight and enforcement to ensure the ability of all citizens to vote.

Court challenges related to "one man, one vote" and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 finally provided the groundwork for federal court rulings. In 1972, the federal court required the legislature to create a statewide redistricting plan to correct the imbalances in representation in the legislature related to population patterns.[53] Redistricting, together with federal oversight of voter registration and election practices, enabled hundreds of thousands of Alabama citizens, both white and black, to vote and participate for the first time in the political system.

Late 20th century (1975–2000)

[edit]Throughout the 1970s, Alabama continued to struggle with issues related to racial inequality and segregation. In 1972, federal court ordered the city of Birmingham to desegregate its public schools. The state continued to be a focal point of the Civil Rights Movement, with organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee remaining active in the state. In 1991, a federal court ordered the state to redraw its congressional districts to ensure greater representation for African American voters.[64]

In 1974, George Wallace, who as governor stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama in 1963 to block the enrollment of African American students, was re-elected to the governorship for a third term. However, Wallace was no longer a segregationist. He now focused more on issues such as economic development and support for education during his final terms in office.

As agriculture faded in importance, the manufacturing and finance sectors flourished. Tourist attractions such as Gulf Shores and Orange Beach drawing visitors from across the country. Crisis locations in the Civil Rights era became tourist attractions.[65]

21st century (2001–present)

[edit]The 21st century saw Alabama continue to emphasize economic growth and a political transformation away from Democrats toward the Republican Party in state and national elections. It made significant investments in education, health care, infrastructure, and economic development. Alabama elected the first Republican governor since Reconstruction, Bob Riley, in 2002. He narrowly defeated incumbent Don Siegelman, the last Democrat to be governor. Riley improved the public education system, expanded Medicaid, and implemented a tax reform plan. He was reelected in 2006. In May 2007, he announced that the German corporation ThyssenKrupp would build a state-of-the-art steel mill north of Mobile. Total cost ran up to $5 billion, the largest foreign project in U.S. business history. The mill now employs 2,700 workers.[66] Automobile manufacturers came to Alabama, with Mercedes-Benz in Tuscaloosa County, and Hyundai Motors in Montgomery County. Aerospace giant, Airbus, built a large manufacturing facility in Mobile County.[67] Huntsville, in north Alabama's Tennessee River Valley, is the fastest growing metropolitan region of Alabama, that is home to one of the per capita most educated regions in the United States. Huntsville is home to NASA's U.S. Space & Rocket Center and Space Camp. Huntsville also has a large defense industry presence.[68]

In 2015, state budget reductions of $83 million resulted in the closing of five parks per Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources ($3 million). In addition, the state cut services at driver's license offices, closing most in several black-majority counties. This made voter registration more difficult, as the offices had offered both services.[69] As of 2018, the state of Alabama offers online voter registration.

See also

[edit]- Thomas M. Owen – Historian of Alabama

- List of the oldest buildings in Alabama

- History of Baptists in Alabama

- Black Belt in the American South

- Deep South

- Women's suffrage in Alabama

- History of slavery in Alabama

- City timelines

- Timeline of Birmingham, Alabama

- Timeline of Huntsville, Alabama

- Timeline of Mobile, Alabama

- Timeline of Montgomery, Alabama

References

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alabama". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 01 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 459–464.

- ^ "Woodland Period - Fort Smith National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ a b c Glenn Feldman. The Disenfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, p.136

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1900 Federal Census, University of Virginia "Geostat Center: Historical Census Browser". Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2010., accessed March 15, 2008

- ^ Sernett, Milton C. (1997). Bound for the Promised Land: African American Religion and the Great Migration. Duke University Press. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-0-8223-1993-1.

- ^ Sernett, Bound for the Promised Land, 37.

- ^ Tolnay, Stewart Emory; E. M. Beck (1995). A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882–1930. University of Illinois Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-252-06413-5.

- ^ Thomas, James D.; William Histaspas Stewart (1988). Alabama Government & Politics. U of Nebraska Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8032-9181-2.

- ^ Bullock, Charles S.; Mark J. Rozell (2006). The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7425-5344-6.

- ^ Alabama - HISTORY. history.com. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Prentice, Guy (2003). "Basteln Bastelanleitung Bastelanleitungen Bastelvorlagen Bastelideen". Southeast Chronicles. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ^ "Alabama". The New York Times Almanac 2004. August 11, 2006. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Welch, Paul D. (1991). Moundville's Economy. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0512-2. OCLC 21330955.

- ^ Walthall, John A. (1990). Prehistoric Indians of the Southeast-Archaeology of Alabama and the Middle South. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0552-1. OCLC 26656858.

- ^ Townsend, Richard F. (2004). Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10601-7. OCLC 56633574.

- ^ F. Kent Reilly; James Garber, eds. (2004). Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71347-5. OCLC 70335213.

- ^ Finger, John R. (2001). Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Indiana University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-253-33985-5.

- ^ About North Georgia (1994–2006). "Moundbuilders, North Georgia's early inhabitants". Golden Ink. Archived from the original on June 4, 2001. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^ "Alabama Indian Tribes". Indian Tribal Records. AccessGenealogy.com. 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "Mound at Fort Toulouse – Fort Jackson Park". University of Alabama.

- ^ Jenkins, Ned J.; Sheldon, Craig T. (2016). "Late Mississippian/Protohistoric Ceramic Chronology and Cultural Change in the Lower Tallapoosa and Alabama River Valleys". Journal of Alabama Archaeology. 62.

- ^ William Garrott Brown, Albert James Pickett, A History of Alabama, for Use in Schools: Based as to Its Earlier Parts on the Work of Albert J. Pickett, University Publishing Company, 1900, p. 56

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alabama". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 01 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 459–464, see pages 462 to 464.

History.—...

- ^ Murray Rothbard (1962). The Panic of 1819: Reactions and Policies. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 81. ISBN 9781610163705.

- ^ John T. Ellisor (2010). The Second Creek War: Interethnic Conflict and Collusion on a Collapsing Frontier. U of Nebraska Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780803234215.

- ^ Austin L. Venable, "William L. Yancey's Transition from Unionism to State Rights." Journal of Southern History 10.3 (1944): 331–342.

- ^ Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, "A Meaning for Turner's Frontier: Part II: The Southwest Frontier and New England." Political Science Quarterly 69.4 (1954): 565–602 in JSTOR.

- ^ J. Mills Thornton, III, Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800–1860 (1978)

- ^ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Ordinances and Constitution of the State of Alabama Archived February 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rogers, ch 12

- ^ Walter Lynwood Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (1905) pp 251–4 online edition

- ^ Rogers et al. Alabama p 244-45

- ^ Rogers et al. Alabama, p 247-58

- ^ Wilson Fallin Jr., Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama (2007), pp 52–53

- ^ Rogers, et al. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (1994) 288–342

- ^ Frances Roberts, "William Manning Lowe and the Greenback Party in Alabama." Alabama Review 5 (1952): 100–21.

- ^ William Warren Rogers, "The Farmers Alliance in Alabama," Alabama Review 15 (1962): 5–18.

- ^ Rogers, et al. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (1994) 343-54.

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1900 US Census, University of Virginia[permanent dead link], accessed March 15, 2008

- ^ Sheldon Hackney, Populism to Progressivism in Alabama (1969), Covers 1892 1910

- ^ Allen Jones, "Political reforms of the Progressive era" Alabama Review (1968) 21#3 pp 173-194 in Wiggins, ed., From Civil War to Civil Rights—Alabama, 1860–1960: An Anthology from the Alabama Review (1987) pp 203–220.

- ^ Rogers, et al. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (1994) 355-75

- ^ James Fletcher Doster, Railroads in Alabama politics: 1875–1914 (1957).

- ^ James F Doster, "Comer, Smith and Jones: Alabama's Railroad War," in Wiggins, ed., From Civil War to Civil Rights—Alabama, 1860–1960: An Anthology from the Alabama Review (1987) pp 221–30.

- ^ Rogers et al. Alabama pp 362–67

- ^ Rogers et al. Alabama pp 370–75

- ^ James Benson Sellers, The prohibition movement in Alabama, 1702 to 1943 (U of North Carolina Press, 1943.

- ^ Jones, "Political Reforms of the Progressive Era," pp. 175—206.

- ^ Mary Martha Thomas, The New Woman in Alabama: Social Reforms, and Suffrage, 1890–1920 (U of Alabama Press, 19920.

- ^ a b Rogers et al. Alabama pp 277-287.

- ^ Birmingham's Population, 1880–2000 Archived January 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ethel Armes and James R. Bennett, The story of coal and iron in Alabama (U of Alabama Press, 2011).

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2007. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c George Mason University, United States Election Project: Alabama Redistricting Summary, accessed 10 Mar 2008 Archived October 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Feldman (1999)

- ^ Birmingham's Impact on the Homefront. Vulcan Park & Museum. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Allen Cronenberg, Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II (University of Alabama Press, 2003).

- ^ a b Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant tornadoes, 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: Environmental Films. pp. 922–925. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- ^ a b c F. C. Pate (United States Weather Bureau) (October 1946). "The Tornado at Montgomery, Alabama, February 12, 1945". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 27 (8). American Meteorological Society: 462–464. JSTOR 26257954. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Flynt, Wayne (February 5, 2016). Poor But Proud. 6913: University of Alabama Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Flynt, Wayne (February 5, 2016). Poor But Proud. 6973: University of Alabama Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Flynt, Wayne (February 5, 2016). Poor But Proud. 7035: University of Alabama Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Historical Census Browser, 1960 US Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 13, 2008

- ^ a b CHANDA TEMPLE and JEFF HANSEN, "Ministers' homes, churches among bomb targets" Archived July 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, AL.com, July 16, 2000, accessed February 3, 2015

- ^ Gerald R. Webster,"Congressional redistricting and African-American representation in the 1990s: an example from Alabama." Political Geography 12.6 (1993): 549-564.

- ^ Glenn T. Eskew, "From civil war to civil rights: selling Alabama as heritage tourism." International journal of hospitality & tourism administration 2.3-4 (2001): 201-214.

- ^ "Sweet Home, Alabama: ThyssenKrupp opens steel manufacturing facility" Plant Engineering Dec 14, 2010 online

- ^ Charles J. Spindler, "Winners and losers in industrial recruitment: Mercedes-Benz and Alabama." State & Local Government Review (1994): 192–204 online.

- ^ Madhuri Sharma, "Spatial perspectives on diversity and economic growth in Alabama, 1990–2011." Southeastern Geographer 56.3 (2016): 320-345. online

- ^ Mike Cason State to close 5 parks, cut back services at driver license offices Alabama Media Group, September 30, 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]Overviews

[edit]- Encyclopedia of Alabama (2008) Online coverage of history, culture, geography, and natural environment. online

- Rogers, William Warren, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flynt. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (3rd ed. 2018; 1st ed. 1994), 816pp; the standard scholarly history online older edition; online 2018 edition

- Alabama State Department of Education. History of Education in Alabama (Bulletin 1975, No. 7.O) Online free

- Bridges, Edwin C. Alabama: The Making of an American State (2016) 264pp excerpt

- Dodd, Donald B. Historical Atlas of Alabama (1974) online free

- Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century (2004)

- Flynt, J. Wayne. "Alabama." in Religion in the Southern States: A Historical Study, edited by Samuel S. Hill. 1983

- Flynt, J. Wayne. Poor But Proud: Alabama's Poor Whites 1989.

- Flynt, J. Wayne. Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie (1998)

- Hamilton, Virginia. Alabama, a bicentennial history (1977) online; short popular history

- Holley, Howard L. A History of Medicine in Alabama. 1982.

- Owen, Thomas M. History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography 4 vols. 1921. online

- Jackson, Harvey H. Inside Alabama: A Personal History of My State (2004)

- Thomas, Mary Martha. Stepping out of the Shadows: Alabama Women, 1819–1990 (1995)

- Thornton, J. Mills. Archipelagoes of My South: Episodes in the Shaping of a Region, 1830–1965 (2016) online; scholarly essays on political episodes.

- Webb, Samuel L., and Margaret Armbrester, eds. Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State (University of Alabama Press, 2001).

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk, ed. From Civil War to Civil Rights—Alabama, 1860–1960: An Anthology from the Alabama Review (U of Alabama Press, 1987). 29 scholarly essays by experts.

- Williams, Benjamin Buford. A Literary History of Alabama: The Nineteenth Century 1979.

- WPA. Guide to Alabama (1939)

Local history

[edit]See the individual articles on each locality.

- Brownell, Blaine A. "Birmingham, Alabama: New South City in the 1920s." Journal of Southern History 38 (1972): 21–48. in JSTOR

- English, Bertis D. Civil Wars, Civil Beings, and Civil Rights in Alabama's Black Belt: A History of Perry County (University Alabama Press, 2020).

- Fallin Jr, Wilson. The African American Church in Birmingham, Alabama, 1815–1963: A Shelter in the Storm (Routledge, 2017).

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. Urban Emancipation: Popular Politics in Reconstruction Mobile, 1860–1890. (2002). 301 pp. ISBN 0-8071-2837-6.

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. "Railroad Subsidies and Black Aspirations: The Politics of Economic Development in Reconstruction Mobile, 1865–1879." Civil War History 39#3 (1993): 240–256.

- Harris, Carl V. Political Power in Birmingham, 1871–1921 1977.

- Norrell, Robert J. "Caste in Steel: Jim Crow Careers in Birmingham, Alabama." Journal of American History 73 (December 1986): 669–94. in JSTOR

- Thornton III, J. Mills. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma (2002) excerpt

- WPA. Guide to Alabama (1939)

Pre 1876

[edit]- "Alabama" in The American year-book and national register for 1869 (1869) online pp 275–280.

- Abernethy, Thomas Perkins The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815–1828 (1922) online free

- Barney, William L. The Secessionist Impulse: Alabama and Mississippi in 1860. (1974).

- Bethel, Elizabeth. "The Freedmen's Bureau in Alabama," Journal of Southern History Vol. 14, No. 1, Feb. 1948 pp. 49–92 online at JSTOR

- Bond, Horace Mann. "Social and Economic Forces in Alabama Reconstruction," Journal of Negro History 23 (1938):290–348 in JSTOR

- Dupre, Daniel S.. Alabama's Frontiers and the Rise of the Old South (Indiana UP, 2017) online review

- Dupre, Daniel. "Ambivalent Capitalists on the Cotton Frontier: Settlement and Development in the Tennessee Valley of Alabama." Journal of Southern History 56 (May 1990): 215–40. Online at JSTOR

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. Reconstruction in Alabama: From Civil War to Redemption in the Cotton South (LSU Press, 2017) 464 pages; a standard scholarly history replacing Fleming 1905

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. "Reconstruction in Alabama" Alabama Encyclopedia (2017) online

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. "" To Give Our Votes to the Party": Black Political Agitation and Agricultural Change in Alabama, 1865–1870." Journal of American History 76#2 (1989): 489–505.

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. "Radical Republicanism and the White Yeomanry During Alabama Reconstruction, 1865–1868." Journal of Southern History 54 (1988): 565–96. JSTOR

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. "The Ku Klux Klan: property crime and the plantation system in Reconstruction Alabama." Agricultural history 71.2 (1997): 186–206.

- Fleming, Walter L. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (1905). a detailed study; Dunning School full text online from Project Gutenberg

- Going, Allen J. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874–1890. 1951.

- Hamilton, Peter Joseph. The Reconstruction Period (1906), full length history of era; Dunning School approach; 570 pp; ch 12 on Alabama

- Jordan, Weymouth T. Ante-Bellum Alabama: Town and Country. (1957).

- Kolchin, Peter. First Freedom: The Response of Alabama Blacks to Emancipation and Reconstruction (1972).

- McIlwain, Christopher Lyle. Civil War Alabama (University of Alabama Press, 2016); 456 pp; a major scholarly survey. [Will excerpt]

- McWhiney, Grady. "Were the Whigs a Class Party in Alabama?" Journal of Southern History 23 (1957): 510–22. Online at JSTOR

- Moore, A. B. "Railroad Building in Alabama During the Reconstruction Period," Journal of Southern History (1935) 1#4 pp. 421–441 in JSTOR

- Rogers, William Warren, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flynt. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (3rd ed. 2018; 1st ed. 1994), 816pp; the standard scholarly history; online 2018 edition

- Schweninger, Loren. "James Rapier of Alabama and the Noble Cause of Reconstruction," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (1982) pp. 79–100.

- Sellers, James B. Slavery in Alabama 1950.

- Severance, Ben H. "To Fight and Die for Dixie: Alabama’s Manpower Contribution to the Confederate War Effort, 1861–1865." Alabama Review,74#4 (2022), pp. 283–303. doi:10.1353/ala.2022.0029.

- Sterkx, Henry Eugene. Partners in Rebellion: Alabama Women in the Civil War (1970).

- Thornton, J. Mills III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800–1860 (1978). online edition

- Wiener, Jonathan M. Social Origins of the New South; Alabama, 1860–1885. (1978).

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865–1881 (1991)

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. "Alabama: Democratic Bulldozing and Republican Folly." in Reconstruction and Redemption in the South, edited by Otto H. Olson. (1980).

Since 1876

[edit]- Barnard, William D. Dixiecrats and Democrats: Alabama Politics, 1942–1950 (1974)

- Bond, Horace Mann. Negro Education in Alabama: A Study in Cotton and Steel (1939). online, a famous classic

- Cronenberg, Allen. Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II (University of Alabama Press, 2003).

- Feldman, Glenn. Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915–1949 (1999)

- Feldman, Glenn. "Southern Disillusionment with the Democratic Party: Cultural Conformity and 'the Great Melding' of Racial and Economic Conservatism in Alabama during World War II," Journal of American Studies 43 (Aug. 2009), 199–230.

- Feldman, Glenn. The Irony of the Solid South: Democrats, Republicans, and Race, 1865–1944 (University of Alabama Press; 2013) 480 pages; how the South became "solid" for the Democrats, then began to shift with World War II.

- Frederick, Jeff. Stand Up For Alabama: Governor George Wallace (University of Alabama Press, 2007).

- Grafton, Carl, and Anne Permaloff. Big Mules and Branchheads: James E. Folsom and Political Power in Alabama 1985.

- Hackney, Sheldon. Populism to Progressivism in Alabama 1969.

- Hamilton, Virginia. Lister Hill: Statesman from the South 1987.

- Jett, Brandon T. " 'We Crave to Become a Vital Force in this Community': Police Brutality and African American Activism in Birmingham, Alabama, 1920-1945" Alabama Review (2022) 75#1 pp. 50–72 DOI: 10.1353/ala.2022.0013

- Jones, Allen. "Political reforms of the progressive era" Alabama Review (1968) 21#3 pp 173–194.

- Key, V. O. Jr. Southern Politics in State and Nation. 1949.

- Lesher, Stephan. George Wallace: American Populist (1995)

- Norrell, Robert J. "Labor at the Ballot Box: Alabama Politics from the New Deal to the Dixiecrat Movement." Journal of Southern History 57 (May 1991): 201–34. in JSTOR

- Oliff, Martin T., ed. The Great War in the Heart of Dixie: Alabama During World War I (2008)

- Permaloff, Anne, and Carl Grafton. Political Power in Alabama (University of Georgia Press, 1995)

- Sellers, James B. The Prohibition Movement in Alabama, 1702–1943 1943.

- Thomas, Mary Martha. The New Women in Alabama: Social Reform and Suffrage, 1890–1920 (1992)

- Thomas, Mary Martha. Riveting and Rationing in Dixie: Alabama Women and the Second World War (1987)

Historiography and memory

[edit]- Atkins, Leah Rawls. “The Alabama Historical Association: The First Fifty Years.” Alabama Review 50#4 (1997): 243–266.

- Brown, Lynda et al. eds. Alabama History: An Annotated Bibliography, (Greenwood, 1998).

- Bridges, Edwin C. "A Tribute to Mills Thornton" Alabama Review (2014) 67#1 pp 4–9.

- Cox, Richard J. “Alabama’s Archival Heritage, 1850-1985.” Alabama Review 40#4 (1987): 284–307.

- Kennington, Kelly. "Slavery in Alabama: A Call to Action." Alabama Review 73.1 (2020): 3-27. excerpt

- Mathis, Ray. "Alabama Freedmen, Politics, And Progressive Historiography: An Essay-Review." Georgia Historical Quarterly 58.4 (1974): 414–421. online