Prayagraj

Prayagraj

Allahabad | |

|---|---|

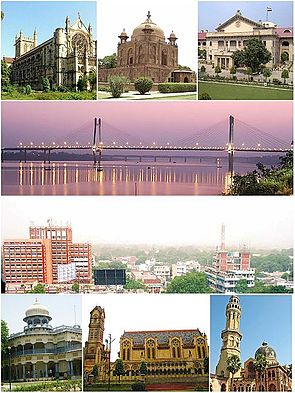

Clockwise from top left: All Saints Cathedral, Khusro Bagh, the Allahabad High Court, the New Yamuna Bridge near Sangam, the skyline of Civil Lines, the University of Allahabad, Thornhill Mayne Memorial at Chandrashekhar Azad Park and Anand Bhavan | |

| Etymology: King of the Prayagas | |

| Nicknames: | |

Location of Prayagraj in Uttar Pradesh | |

| Coordinates: 25°26′09″N 81°50′47″E / 25.43583°N 81.84639°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| Division | Prayagraj |

| District | Prayagraj |

| Earliest mention | c. 1200–1000 BCE[3] |

| Established as Ilahabas | 1584 |

| Established as a city | 1801 |

| Named for | Panch Prayag |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Prayagraj Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Ganesh Kesarwani (BJP) |

| • Lok Sabha MP | Ujjwal Raman Singh (INC) |

| Area | |

• Total | 365 km2 (140.9 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 10 |

| Elevation | 98 m (321.52 ft) |

| Population (2020–2011 hybrid)[4] | |

• Total | 1,536,218 |

| • Rank | 7th in Uttar Pradesh 36th in India |

| • Density | 4,200/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro rank | 40th |

| Demonyms | Allahabadi Ilahabadi[5] |

| Language | |

| • Official | Hindi[6] |

| • Additional official | Urdu[6] |

| • Regional | Awadhi[7] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 211001–211018 |

| Telephone code | +91-532 |

| Vehicle registration | UP-70 |

| Sex ratio | 852 ♀/1000♂ |

| Website | prayagraj |

Prayagraj (/ˈpreɪəˌɡrɑːdʒ, ˈpraɪə-/; ISO: Prayāgarāja), formerly Allahabad is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.[8][9] It is the administrative headquarters of the Prayagraj district, the most populous district in the state and 13th most populous district in India and the Prayagraj division. The city is the judicial capital of Uttar Pradesh with the Allahabad High Court being the highest judicial body in the state. As of 2011,[update] Prayagraj is the seventh most populous city in the state, thirteenth in Northern India and thirty-sixth in India, with an estimated population of 1.53 million in the city.[10][11] In 2011, it was ranked the world's 40th fastest-growing city.[12][13] The city, in 2016, was also ranked the third most liveable urban agglomeration in the state (after Noida and Lucknow) and sixteenth in the country.[14] Hindi is the most widely spoken language in the city.

Prayagraj lies close to Triveni Sangam, the "three-river confluence" of the Ganges, Yamuna, and the mythical Sarasvati.[1] It plays a central role in Hindu scriptures. The city finds its earliest reference as one of the world's oldest known cities in Hindu texts and has been venerated as the holy city of Prayāga in the ancient Vedas. Prayagraj was also known as Kosambi in the late Vedic period, named by the Kuru rulers of Hastinapur, who developed it as their capital. Kosambi was one of the greatest cities in India from the late Vedic period until the end of the Maurya Empire, with occupation continuing until the Gupta Empire. Since then, the city has been a political, cultural and administrative centre of the Doab region.

Akbarnama mentions that the Mughal emperor Akbar founded a great city in Allahabad. Abd al-Qadir Badayuni and Nizamuddin Ahmad mention that Akbar laid the foundations of an imperial city there which was called Ilahabas or Ilahabad.[15][16] In the early 17th century, Allahabad was a provincial capital in the Mughal Empire under the reign of Jahangir.[17] In 1833, it became the seat of the Ceded and Conquered Provinces region before its capital was moved to Agra in 1835.[18] Allahabad became the capital of the North-Western Provinces in 1858 and was the capital of India for a day.[19] The city was the capital of the United Provinces from 1902[19] to 1920[20] and remained at the forefront of national importance during the struggle for Indian independence.[21]

Prayagraj is one of the international tourism destinations, securing the second position in terms of tourist arrivals in the state after Varanasi.[22] Located in southern Uttar Pradesh, the city covers 365 km2 (141 sq mi).[4] Although the city and its surrounding area are governed by several municipalities, a large portion of Prayagraj district is governed by the Prayagraj Municipal Corporation. The city is home to colleges, research institutions and many central and state government offices, including High court of Uttar Pradesh. Prayagraj has hosted cultural and sporting events, including the Prayag Kumbh Mela and the Indira Marathon. Although the city's economy was built on tourism, most of its income now derives from real estate and financial services.[23]

Etymology

[edit]The location at the confluence of Ganges and Yamuna rivers has been known in ancient times as Prayāga, which means "place of a sacrifice" in Sanskrit (pra-, "fore-" + yāj-, "to sacrifice").[24] It was believed that god Brahma performed the very first sacrifice (yāga, yajna) in this place.[25][26]

The word prayāga has been traditionally used to mean "a confluence of rivers". For Allahabad, it denoted the physical meeting point of the rivers Ganges and Yamuna in the city. An ancient tradition has it that a third river, invisible Sarasvati, also meets there with the two. Today, Triveni Sangam (or simply Sangam) is a more frequently used name for the confluence.

Prayagraj (Sanskrit: Prayāgarāja), meaning "the king among the five prayāgas", is used as a term of respect to indicate that this confluence is the most splendid one of the five sacred confluencies in India.[27]

The Mughal emperor Akbar visited the region in 1575 and was so impressed by the strategic location of the site that he ordered a fort be constructed.[28] The fort was constructed by 1584 and called Ilahabas or "Abode of Allah", later changed to Allahabad under Shah Jahan. Speculations regarding its name, however, exist. Because of the surrounding people calling it Alhabas, has led to some people[who?] holding the view that it was named after Alha from Alha's story.[29] James Forbes' account of the early 1800s claims that it was renamed Allahabad or "Abode of God" by Jahangir after he failed to destroy the Akshayavat tree. The name, however, predates him, with Ilahabas and Ilahabad mentioned on coins minted in the city since Akbar's rule, the latter name became predominant after the emperor's death. It has also been thought to not have been named after Allah but ilaha (the gods). Shaligram Shrivastav claimed in Prayag Pradip that the name was deliberately given by Akbar to be construed as both Hindu ("ilaha") and Muslim ("Allah").[16]

Over the years, a number of attempts were made by the BJP-led governments of Uttar Pradesh to rename Allahabad to Prayagraj. In 1992, the planned rename was shelved when the chief minister, Kalyan Singh, was forced to resign following the Babri Masjid demolition. 2001 saw another attempt led by the government of Rajnath Singh which remained unfulfilled.[30] The rename finally succeeded in October 2018 when the Yogi Adityanath-led government officially changed the name of the city to Prayagraj.[31][32]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]The earliest mention of Prayāga and the associated pilgrimage is found in Rigveda Pariśiṣṭa (supplement to the Rigveda, c. 1200–1000 BCE).[3] It is also mentioned in the Pali canons of Buddhism, such as in section 1.7 of Majjhima Nikaya (c. 500 BCE), wherein the Buddha states that bathing in Payaga (Skt: Prayaga) cannot wash away cruel and evil deeds, rather the virtuous one should be pure in heart and fair in action.[33] The Mahabharata (c. 400 BCE–300 CE) mentions a bathing pilgrimage at Prayag as a means of prāyaścitta (atonement, penance) for past mistakes and guilt.[34] In Tirthayatra Parva, before the great war, the epic states "the one who observes firm [ethical] vows, having bathed at Prayaga during Magha, O best of the Bharatas, becomes spotless and reaches heaven."[35] In Anushasana parva, after the war, the epic elaborates this bathing pilgrimage as "geographical tirtha" that must be combined with manasa-tirtha (tirtha of the heart) whereby one lives by values such as truth, charity, self-control, patience and others.[36]

Prayāga is mentioned in the Agni Purana and other Puranas with various legends, including being one of the places where Brahma attended a yajna (homa), and the confluence of river Ganges, Yamuna and mythical Saraswati site as the king of pilgrimage sites (Tirtha Raj).[37] Other early accounts of the significance of Prayag to Hinduism is found in the various versions of the Prayaga Mahatmya, dated to the late 1st-millennium CE. These Purana-genre Sanskrit texts describe Prayag as a place "bustling with pilgrims, priests, vendors, beggars, guides" and local citizens busy along the confluence of the rivers (sangam).[38][39] Prayaga is also mentioned in the Hindu epic Ramayana, a place with the legendary Ashram of sage Bharadwaj.[40]

In Jainism

[edit]

Purimtal Jain Tirth, located in Prayagraj (formerly known as Purimtal and later known as Allahabad), is a site of religious and historical significance for Jains. This ancient pilgrim site is revered as the spot where Rishabhanatha, the first Tirthankara, achieved Kevala jnana as per Jain beliefs.[41] As documented in Vividha Tirtha Kalpa by Acharya Jinaprabhasuri, Purimtal once featured numerous Jain temples. Rishabhanatha is said to have attained omniscience under the Akshayavat tree. This tree, often referred to as the "indestructible" tree in legends, is a point of spiritual reverence in other religions as well. The site also holds importance in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Originally, sandalwood footprints of Rishabhanatha were placed beneath the tree, which were later replaced with stone replicas following theft.[42]

Acharya Hemachandrasuri's Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra describes Purimtal as a 'hub of Jain activity', where multiple Tirthankaras, including Mahavira, visited and meditated. Mahavira is said to have practiced deep meditation in the Shakatmukh Udyan nearby, and a divine Samavasaran (transl. three-tiered pavilion for delivering sermons) was constructed here. Acharya Arnikaputra is also said to have attained omniscience and moksha near the Triveni Sangam, the confluence of the Ganges, Yamuna, and Saraswati rivers.[43]

In the 15th century, Akbar constructed a fort enclosing the Akshayavat tree. During British rule, public access to the fort was restricted, and the shrine was relocated to the Patalpuri Śvetāmbara Jain Temple on the fort’s outskirts. While the Patalpuri Śvetāmbara Jain Temple houses a tree worshiped as the Akshayvat, many believe the original Akshayvat is in an underground temple within the fort. Maps from the British Library confirm this, showing the original temple’s location at the fort's center.[44]

Purimtal is home to five Jain temples, including four Digambara and one Śvetāmbara temple. The Śvetāmbara Jain temple features a marble idol of Rishabhanatha, dating back to the 11th century CE. Alongside the idol, the temple enshrines images of other Tirthankaras, such as Vimalnatha, Parshvanatha, Mahavira, and Shantinatha. Footprints of Jain monks are also installed here. The Allahabad Museum further highlights the region's Jain heritage, displaying ancient idols and artefacts excavated from nearby areas.[45]

Purimtal is associated with numerous milestones in Jain history, including: -

- Rishabhanatha's attainment of omniscience beneath the Akshayvat tree.[42][43]

- The creation of the first Samavasaran (transl. multistoreyed divine preaching hall) of this Avasarpiṇī.[42][43]

- The establishment of the first Chaturvidha Jain Sangh (fourfold Jain congregation) of this Avasarpiṇī.[42][43]

- Marudevi's attainment of moksha, marking the first moksha of this Avasarpiṇī.[42][43]

- The composition of the first Dvādaśāṅgī scriptures by Ganadhara Pundarika, a disciple of Rishabhanatha.[42][43]

The Akshayvat tree remains a key attraction. Ongoing efforts to preserve and document Purimtal’s Jain heritage ensure its enduring relevance to the community and the broader historical narrative.[45]

Archaeology and inscriptions

[edit]

Inscription evidence from the famed Ashoka edicts containing Allahabad Pillar – also referred to as the Prayaga Bull pillar – adds to the confusion about the antiquity of this city.[47][48] Excavations have revealed Northern Black Polished Ware dating to 600–700 BCE.[37] According to Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti, "... there is nothing to suggest that modern Prayag (i e. modern Allahabad) was an ancient city. Yet it is inconceivable that one of the holiest places of Hinduism, Prayag or the confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna should be without a major ancient city." Chakrabarti suggests that the city of Jhusi, opposite the confluence, must have been the "ancient settlement of Prayag".[49] Archaeological surveys since the 1950s has revealed the presence of human settlements near the sangam since c. 800 BCE.[47][48]

Along with Ashoka's Brahmi script inscription from the 3rd century BCE, the pillar has a Samudragupta inscription, as well as a Magha Mela inscription of Birbal of Akbar's era. It states,

In the Samvat year 1632, Saka 1493, in Magha, the 5th of the waning moon, on Monday, Gangadas's son Maharaja Birbal made the auspicious pilgrimage to Tirth Raj Prayag. Saphal scripsit.

– Translated by Alexander Cunningham (1879)[50]

These dates correspond to about 1575 CE, and confirm the importance and the name Prayag.[50][51] According to Cunningham, this pillar was brought to Allahabad from Kaushambi by a Muslim Sultan, and that in some later century before Akbar, the old city of Prayag had been deserted.[52] Other scholars, such as Krishnaswamy and Ghosh disagree.[51] In a paper published in 1935, they state that the pillar was always at its current location based on the inscription dates on the pillar, lack of textual evidence for the move in records left by Muslim historians and the difficulty in moving the massive pillar.[53] Further, like Cunningham, they noted that many smaller inscriptions were added on the pillar over time. Quite many of these inscriptions include a date between 1319 CE and 1575 CE, and most of these refer to the month Magha. According to Krishnaswamy and Ghosh, these dates are likely related to the Magh Mela pilgrimage at Prayag, as recommended in the ancient Hindu texts.[54]

In papers published about 1979, John Irwin – a scholar of Indian Art History and Archaeology, concurred with Krishnaswamy and Ghosh that the Allahabad pillar was never moved and was always at the confluence of the rivers Ganges and Yamuna.[47][48] According to Irwin, an analysis of the minor inscriptions and ancient scribblings on the pillar first observed by Cunningham, also noted by Krishnaswamy and Ghosh, reveals that these included years and months, and the latter "always turns out to be Magha, which also gives it name to the Magh Mela", the Prayaga bathing pilgrimage festival of the Hindus.[48] He further stated that the pillar origins were undoubtedly pre-Ashokan based on the new evidence from the archaeological and geological surveys of the triveni site (Prayaga), the major and minor inscriptions as well as textual evidence, taken together.[47][48] Archaeological and geological surveys done since the 1950s, states Irwin, have revealed that the rivers – particularly Ganges – had a different course in distant past than now. The original path of river Ganges at the Prayaga confluence had settlements dating from the 8th century BCE onwards.[48] According to Karel Werner – an Indologist known for his studies on religion particularly Buddhism, the Irwin papers "showed conclusively that the pillar did not originate at Kaushambi", but had been at Prayaga from pre-Buddhist times.[55]

Early medieval period

[edit]The 7th-century Buddhist Chinese traveller Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) in Fascicle V of Dà Táng Xīyù Jì (Great Tang Records on the Western Regions) explicitly mentions Prayaga as both a country and a "great city" where the Yamuna river meets Ganges river. He states that the great city has hundreds of "deva temples" and to the south of the city are two Buddhist institutions (a stupa built by Ashoka and a monastery). His 644 CE memoir also mentions the Hindu bathing rituals at the junction of the rivers, where people fast near it and then bathe believing that this washes away their sins. Wealthy people and kings come to this "great city" to give away alms at the Grand Place of Almsgiving. According to Xuanzang's travelogue, the confluence is to the east of this "great city" and the site where alms are distributed every day.[56][57] Kama MacLean – an Indologist who has published articles on the Kumbh Mela predominantly based on the colonial archives and English-language media,[58] states based on emails from other scholars and a more recent interpretation of the 7th-century Xuanzang memoir, that Prayag was also an important site in 7th-century India of a Buddhist festival. She states that Xuanzang festivities at Prayag featured a Buddha statue and involved alms giving, consistent with Buddhist practices.[59] According to Li Rongxi – a scholar credited with a recent and complete translation of a critical version of the Dà Táng Xīyù Jì, Xuanzang mentions that the site of the alms-giving is a deva temple, and the alms-giving practice is recommended by the "records at this temple". Rongxi adds that the population of Prayaga was predominantly heretics (non-Buddhists, Hindus), and affirms that Prayaga attracted festivities of deva-worshipping heretics and also the orthodox Buddhists.[56]

Xuanzang also describes a ritual-suicide practice at Prayaga, then concludes it is absurd. He mentions a tree with "evil spirits" that stands before another deva temple. People commit suicide by jumping from it in the belief that they will go to heaven.[56] According to Ariel Glucklich – a scholar of Hinduism and Anthropology of Religion, the Xuanzang memoir mentions both the superstitious devotional suicide and narrates a story of how a Brahmin of a more ancient era tried to put an end to this practice.[57] Alexander Cunningham believed the tree described by Xuanzang was the Akshayavat tree. It still existed at the time of Al-Biruni who calls it as "Prayaga", located at the confluence of Ganga and Yamuna.[60]

The historic literature of Hinduism and Buddhism before the Mughal emperor Akbar use the term Prayag, and never use the term Allahabad or its variants. Its history before the Mughal Emperor Akbar is unclear.[61] In contrast to the account of Xuanzang, the Muslim historians place the tree at the confluence of the rivers. The historian Dr. D. B. Dubey states that it appears that between this period, the sandy plain was washed away by the Ganges, to an extent that the temple and tree seen by the Chinese traveller too was washed away, with the river later changing its course to the east and the confluence shifting to the place where Akbar laid the foundations of his fort.[62]

Henry Miers Elliot believed that a town existed before Allahabad was founded. He adds that after Mahmud of Ghazni captured Asní near Fatehpur, he couldn't have crossed into Bundelkhand without visiting Allahabad had there been a city worth plundering. He further adds that its capture should have been heard when Muhammad of Ghor captured Benares. However, Ghori's historians never noticed it. Akbarnama mentions that the Mughal emperor Akbar founded a great city in Allahabad. 'Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni and Nizamuddin Ahmad mention that Akbar laid the foundations of an Imperial City there which he called Ilahabas.[15]

Mughal rule

[edit]

Abul Fazal in his Ain-i-Akbari states, "For a long time his (Akbar's) desire was to found a great city in the town of Piyag (Allahabad) where the rivers Ganges and Jamuna join... On 13th November 1583 (1st Azar 991 H.) he (Akbar) reached the wished spot and laid the foundations of the city and planned four forts." Abul Fazal adds, "Ilahabad anciently called Prayag was distinguished by His Imperial Majesty [Akbar] by the former name".[63] The role of Akbar in founding the Ilahabad – later called Allahabad – fort and city is mentioned by ʽAbd al-Qadir Badayuni as well.[64]

Nizamuddin Ahmad gives two different dates for Allahabad's foundation, in different sections of Tabaqat-i-Akbari. He states that Akbar laid the foundation of the city at a place of the confluence of Ganges and Jumna which was a very sacred site of Hindus, then gives 1574 and 1584 as the year of its founding, and that it was named "Ilahabas".[64] The next generation of Mughal rulers started calling it Illahabad, and finally, the British started calling it "Allahabad" for ease of pronunciation.[65]

Akbar was impressed by its strategic location for a fort.[29] According to William Pinch, Akbar's motive may have been twofold. One, the armed fort secured the control of fertile Doab region. Second, it greatly increased his visibility and power to the non-Muslims who gathered here for pilgrimage from distant places and who constituted the majority of his subjects.[66] Later, he declared Ilahabas as a capital of one of the twelve divisions (subahs).[67] According to Richard Burn, the suffix "–bas" was deemed to "savouring too much of Hinduism" and therefore the name was changed to Ilahabad by Shah Jahan.[63] This evolved into the two variant colonial-era spellings of Ilahabad (Hindi: इलाहाबाद) and Allahabad.[63][68] According to Maclean, these variant spellings have a political basis, as "Ilaha–" means "the gods" for Hindus, while Allah is the term for God to Muslims.[68]

After Prince Salim's coup against Akbar and a failed attempt to seize Agra's treasury, he came to Allahabad and seized its treasury while setting himself up as a virtually independent ruler.[69] In May 1602, he had his name read in Friday prayers and his name minted on coins in Allahabad. After reconciliation with Akbar, Salim returned to Allahabad, where he stayed before returning in 1604.[70] After capturing Jaunpur in 1624, Prince Khurram ordered the siege of Allahabad. The siege was however, lifted after Parviz and Mahabat Khan came to assist the garrison.[71] During the Mughal war of succession, the commandant of the fort who had joined Shah Shuja made an agreement with Aurangzeb's officers and surrendered it to Khan Dauran on 12 January 1659.[72]

Nawabs of Awadh

[edit]The fort was coveted by the East India Company for the same reasons Akbar built it. British troops were first stationed at Allahabad fort in 1765 as part of the Treaty of Allahabad signed by Lord Robert Clive, Mughal emperor Shah Alam II, and Awadh's Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula.[73] The combined forces of Bengal's Nawab Mir Qasim, Shuja and Shah Alam were defeated by the English at Buxar in October 1764 and at Kora in May 1765. Alam, who was abandoned by Shuja after the defeats, surrendered to the English and was lodged at the fort, as they captured Allahabad, Benares and Chunar in his name. The territories of Allahabad and Kora were given to the emperor after the treaty was signed in 1765.

Shah Alam spent six years in the Allahabad fort and after the takeover of Delhi by the Marathas, left for his capital in 1771 under their protection.[74] He was escorted by Mahadaji Shinde and left Allahabad in May 1771 and in January 1772 reached Delhi. Upon realising the Maratha intent of territorial encroachment, however, Shah Alam ordered his general Najaf Khan to drive them out. Tukoji Rao Holkar and Visaji Krushna Biniwale in return attacked Delhi and defeated his forces in 1772. The Marathas were granted an imperial sanad for Kora and Allahabad. They turned their attention to Oudh to gain these two territories. Shuja was however, unwilling to give them up and made appeals to the English and the Marathas did not fare well at the Battle of Ramghat.[75] In August and September 1773, Warren Hastings met Shuja and concluded a treaty, under which Kora and Allahabad were ceded to the Nawab for a payment of 50 lakh rupees.[76]

Saadat Ali Khan II, after being made the Nawab by John Shore, entered into a treaty with the company and gave the fort to the British in 1798.[77] Lord Wellesley after threatening to annexe the entire Awadh, concluded a treaty with Saadat on abolishing the independent Awadhi army, imposing a larger subsidiary force and annexing Rohilkhand, Gorakhpur and the Doab in 1801.[78]

British rule

[edit]

Acquired in 1801, Allahabad, aside from its importance as a pilgrimage centre, was a stepping stone to the agrarian track upcountry and the Grand Trunk Road. It also potentially offered sizeable revenues to the company. Initial revenue settlements began in 1803.[79] Allahabad was a participant in the 1857 Indian Mutiny,[80] when Maulvi Liaquat Ali unfurled the banner of revolt.[81] During the rebellion, Allahabad, with a number of European troops,[82] was the scene of a massacre.[17]

After the mutiny, the British established a high court, a police headquarters and a public-service commission in Allahabad,[83] making the city an administrative centre.[84] They truncated the Delhi region of the state, merging it with Punjab and moving the capital of the North-Western Provinces to Allahabad (where it remained for 20 years).[20] In January 1858, Earl Canning departed Calcutta for Allahabad.[85] That year he read Queen Victoria's proclamation, transferring control of India from the East India Company to the British Crown (beginning the British Raj), in Minto Park.[86][87] In 1877 the provinces of Agra and Awadh were merged to form the United Provinces,[88] with Allahabad its capital until 1920.[20]

The 1888 session of the Indian National Congress was held in the city,[89] and by the turn of the 20th century, Allahabad was a revolutionary centre.[90] Nityanand Chatterji became a household name when he hurled a bomb at a European club.[91] In Alfred Park in 1931, Chandrashekhar Azad died when surrounded by British police.[92] The Nehru family homes, Anand Bhavan and Swaraj Bhavan, were centres of Indian National Congress activity.[93] During the years before independence, Allahabad was home to thousands of satyagrahis led by Purushottam Das Tandon, Bishambhar Nath Pande, Narayan Dutt Tiwari and others.[21] The first seeds of the Pakistani nation were sown in Allahabad:[94] on 29 December 1930, Allama Muhammad Iqbal's presidential address to the All-India Muslim League proposed a separate Muslim state for the Muslim-majority regions of India.[95]

Geography

[edit]Cityscape

[edit]Prayagraj's elevation is over 90 m (295 ft) above sea level. The old part of the city, at the south of Prayagraj Junction railway station, consists of neighbourhoods like Chowk, Johnstongunj, Dariyabad, Khuldabad and many more.[96] In the north of the Railway Station, the new city consists of neighbourhoods like Lukergunj, Civil Lines, Georgetown, Tagoretown, Allahpur, Ashok Nagar, Mumfordgunj, Bharadwaj Puram and others which are relatively new and were built during the British rule.[97] Civil Lines is the central business district of the city and is famous for its urban setting, gridiron plan roads[98] and high rise buildings. Built in 1857, it was the largest town-planning project carried out in India before the establishment of New Delhi.[97][98] Prayagraj has many buildings featuring Indo-Islamic and Indo-Saracenic architecture. Although several buildings from the colonial period have been declared "heritage structures", others are deteriorating.[99] Famous landmarks of the city are Allahabad Museum, New Yamuna Bridge, Allahabad University, Triveni Sangam, All Saints Cathedral, Anand Bhavan, Chandrashekhar Azad Park etc.[100] The city experiences one of the highest levels of air pollution worldwide, with the 2016 update of the World Health Organization's Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database finding Prayagraj to have the third highest mean concentration of "PM2.5" (<2.5 μm diameter) particulate matter in the ambient air among all the 2972 cities tested (after Zabol and Gwalior).[101]

Triveni Sangam and Ghats

[edit]

The Triveni Sangam (place where three rivers meet) is the meeting place of Ganges, the Yamuna and mythical Saraswati River, which according to Hindu legends, wells up from underground.[102][103] A place of religious importance and the site for historic Prayag Kumbh Mela held every 12 years, over the years it has also been the site of immersion of ashes of several national leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi in 1948.[102]

The main ghat in Prayagraj is Saraswati Ghat, on the banks of Yamuna. Stairs from three sides descend to the green water of the Yamuna. Above it is a park which is always covered with green grass. There are also facilities for boating here. There are also routes to reach Triveni Sangam by boat from here.[104][105] Apart from this, there are more than 100 raw ghats in Prayagraj.

Topography

[edit]

Prayagraj is in the southern part of Uttar Pradesh, at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna.[106][107] The region was known in antiquity first as the Kuru, then as the Vats country.[108] To the southwest is Bundelkhand, to the east and southeast is Baghelkhand, to the north and northeast is Awadh and to the west is the lower doab (of which Prayagraj is part).[106] The city is divided by a railway line running east–west.[109] South of the railway is the Old Chowk area, and the British-built Civil Lines is north of it. Prayagraj is well placed geographically and culturally.[110] Geographically part of the Ganga-Yamuna Doab (at the mouth of the Yamuna), culturally it is the terminus of the Indian west.[111] The Indian Standard Time longitude (25.15°N 82.58°E) is near the city. According to a United Nations Development Programme report, Prayagraj is in a "low damage risk" wind and cyclone zone.[112] In common with the rest of the doab, its soil and water are primarily alluvial.[113] Pratapgarh is north of the city, Bhadohi is east, Rewa is south, Chitrakoot (earlier Banda) is west, and Kaushambi, which was until recently a part of Allahabad (Prayagraj), is North-West.

Climate

[edit]Prayagraj has a humid subtropical climate common to cities in the plains of North India, designated Cwa in the Köppen climate classification.[114] The annual mean temperature is 26.1 °C (79.0 °F); monthly mean temperatures are 18–29 °C (64–84 °F).[115] Prayagraj has three seasons: a hot, dry summer, a cool, dry winter and a hot, humid monsoon. Summer lasts from March to September with daily highs reaching up to 48 °C in the dry summer (from March to May) and up to 40 °C in the hot and extremely humid monsoon season (from June to September).[115] The monsoon begins in June, and lasts until August; high humidity levels prevail well into September. Winter runs from December to February,[116] with temperatures rarely dropping to the freezing point. The daily average maximum temperature is about 22 °C (72 °F) and the minimum about 9 °C (48 °F).[117] Prayagraj never receives snow,[118] but, experiences dense winter fog due to numerous wood fires, coal fires, and open burning of rubbish—resulting in substantial traffic and travel delays.[116] Its highest recorded temperature is 48.9 °C (120.0 °F) on 9 June 2019, and its lowest is −0.7 °C (31 °F) on 26 December 1961.[115][119]

Rain from the Bay of Bengal or the Arabian Sea branches of the southwest monsoon[120] falls on Allahabad from June to September, supplying the city with most of its annual rainfall of 1,027 mm (40 in).[118] The highest monthly rainfall total, 333 mm (13 in), occurs in August.[121] The city receives 2,961 hours of sunshine per year, with maximum sunlight in May.[119]

| Climate data for Prayagraj (1991–2020, extremes 1901–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

36.3 (97.3) |

42.8 (109.0) |

46.8 (116.2) |

48.8 (119.8) |

48.9 (120.0) |

45.6 (114.1) |

42.7 (108.9) |

39.6 (103.3) |

40.6 (105.1) |

36.2 (97.2) |

32.6 (90.7) |

48.9 (120.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

34.0 (93.2) |

39.9 (103.8) |

41.7 (107.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.6 (92.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

24.9 (76.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 15.7 (60.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 17.0 (0.67) |

17.6 (0.69) |

8.8 (0.35) |

7.0 (0.28) |

13.9 (0.55) |

113.5 (4.47) |

268.0 (10.55) |

238.5 (9.39) |

184.9 (7.28) |

34.7 (1.37) |

4.6 (0.18) |

6.8 (0.27) |

915.3 (36.04) |

| Average rainy days | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 5.5 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 46.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 64 | 53 | 37 | 24 | 29 | 48 | 72 | 76 | 73 | 63 | 60 | 65 | 55 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 224.9 | 244.2 | 263.2 | 274.1 | 292.3 | 206.4 | 143.3 | 180.6 | 184.3 | 259.7 | 256.7 | 244.0 | 2,773.7 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department[122][123][124] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun 1971–1990),[125]Tokyo Climate Center (mean temperatures 1991–2020)[126] | |||||||||||||

Allahabad has been ranked 20th best "National Clean Air City" (under Category 1 >10L Population cities) in India according to 'Swachh Vayu Survekshan 2024 Results' [127]

Biodiversity

[edit]

The Ganga-Jamuna Doab, of which Prayagraj is a part, is on the western Indus-Gangetic Plain region. The doab (including the Terai) is responsible for the city's unique flora and fauna.[128][129] Since the arrival of humans, nearly half of the city's vertebrates have become extinct. Others are endangered or have had their range severely reduced. Associated changes in habitat and the introduction of reptiles, snakes and other mammals led to the extinction of bird species, including large birds such as eagles.[130] The Allahabad Museum, one of four national museums in India, is documenting the flora and fauna of the Ganges and the Yamuna.[131] To protect the rich aquatic biodiversity of river Ganges from escalating anthropogenic pressures, development of a Turtle sanctuary in Prayagraj along with a River Biodiversity Park at Sangam have been approved under Namami Gange programme.

The most common birds found in the city are doves, peacocks, junglefowl, black partridge, house sparrows, songbirds, blue jays, parakeets, quails, bulbuls, and comb ducks.[132] Large numbers of Deer are found in the Trans Yamuna area of Prayagraj. India's first conservation reserve for blackbuck is being created in Prayagraj's Meja Forest Division. Other animals in the state include reptiles such as lizards, cobras, kraits, and gharials.[128] During winter, large numbers of Siberian birds are reported in the sangam and nearby wetlands.[133]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 20,000 | — |

| 1865 | 105,900 | +429.5% |

| 1871 | 143,700 | +35.7% |

| 1881 | 148,500 | +3.3% |

| 1891 | 175,200 | +18.0% |

| 1901 | 172,032 | −1.8% |

| 1911 | 171,697 | −0.2% |

| 1921 | 157,220 | −8.4% |

| 1931 | 173,895 | +10.6% |

| 1941 | 246,226 | +41.6% |

| 1951 | 312,259 | +26.8% |

| 1961 | 411,955 | +31.9% |

| 1971 | 490,622 | +19.1% |

| 1981 | 616,051 | +25.6% |

| 1991 | 792,858 | +28.7% |

| 2001 | 975,393 | +23.0% |

| 2011 | 1,112,544 | +14.1% |

| 2020 | 1,536,218 | +38.1% |

| Sources:[134][135][4] | ||

The 2011 census reported a population of 1,112,544 in the 82 km2 (32 sq mi) area governed by Prayagraj Municipal Corporation, corresponding to a density of 13,600/km2 (35,000/sq mi).[135][137] In January 2020, the boundaries of Prayagraj Municipal Corporation were expanded to 365 km2 (141 sq mi); according to the 2011 census, 1,536,218 people lived within those boundaries; this corresponds to a population density of 4,200/km2 (11,000/sq mi).[4]

Natives of Uttar Pradesh form the majority of Prayagraj's population. With regards to Houseless Census in Prayagraj, total 5,672 families live on footpaths or without any roof cover, this is approximately 0.38 percent of the total population of Prayagraj district. The sex ratio of Prayagraj is 901 females per 1000 males and child sex ratio of is 893 girls per 1000 boys, lower than the national average.[138]

Hindi, the official state language, is the dominant language in Prayagraj. Urdu and other languages are spoken by a sizeable minority. Hindus form the majority of Prayagraj's population; Muslims compose a large minority. According to provisional results of the 2011 national census, Hinduism is majority religion in Prayagraj city with 76.03 percent followers. Islam is the second most practised religion in the city with approximately 21.94 percent following it. Christianity is followed by 0.68 percent, Jainism by 0.10 percent, Sikhism by 0.28 percent and Buddhism by 0.28 percent. Around 0.02 percent stated 'Other Religion', approximately 0.90 percent stated 'No Particular Religion'.

Prayagraj's literacy rate at 86.50 percent is the highest in the region.[139] Male literacy is 90.21 percent and female literacy 82.17 percent.[140] For 2001 census same figure stood at 75.81 and 46.38. As per census 2011, total 1,080,808 people are literate in Prayagraj of which males and females are 612,257 and 468,551 respectively. Among 35 major Indian cities, Prayagraj reported the highest rate of violations of special and local laws to the National Crime Records Bureau.[141]

Administration and politics

[edit]General administration

[edit]Prayagraj division, comprising four districts, is headed by the divisional commissioner of Prayagraj, who is an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer of high seniority, the commissioner is the head of local government institutions (including municipal corporations) in the division, is in charge of infrastructure development in his division, and is also responsible for maintaining law and order in the division.[142][143][144][145] The district magistrate and collector of Prayagraj reports to the divisional commissioner. The current commissioner is Ashish Kumar Goel.[146][147][148][149]

Prayagraj district administration is headed by the district magistrate and collector (DM) of Prayagraj, who is an IAS officer. The DM is in charge of property records and revenue collection for the central government and oversees the elections held in the district. The DM is also responsible for maintaining law and order in the district.[142][150][151][152] The DM is assisted by a chief development officer; five additional district magistrates for finance/revenue, city, rural administration, land acquisition and civil supply; one chief revenue officer; one city magistrate; and three additional city magistrates.[148][149] The district has eight tehsils viz. Sadar, Soraon, Phulpur, Handia, Karchhana, Bara, Meja and Kuraon, each headed by a sub-divisional magistrate.[148]

Police administration

[edit]City comes under the Prayagraj Police Zone and Prayagraj Police Range, Prayagraj Zone is headed by an additional director general-rank Indian Police Service (IPS) officer, and the Prayagraj Range is headed inspector general-rank IPS officer. The district police is headed by a senior superintendent of police (SSP), who is an IPS officer, and is assisted by eight superintendents of police or additional superintendents of police for city, either from the IPS or the Provincial Police Service.[153] Each of the several police circles is headed by a circle officer (CO) in the rank of deputy superintendent of police.[153]

Infrastructure and civic administration

[edit]The development of infrastructure in the city is overseen by the Prayagraj Development Authority (PDA), which comes under the Department of Housing and Urban Planning of Uttar Pradesh government. The divisional commissioner of Prayagraj acts as the ex-officio chairperson of PDA, whereas a vice chairperson, a government-appointed IAS officer, looks after the daily matters of the authority.[154] The current chairperson of PDA is Bhanu Chandra Goswami.[155]

The Prayagraj Nagar Nigam, also called Prayagraj Municipal Corporation, oversees the city's civic infrastructure. The corporation originated in 1864 as the Municipal Board of Allahabad, when the Lucknow Municipal Act was passed by the Government of India.[156][157] In 1867, the Civil Lines and the city were amalgamated for municipal purposes.[156][157] The Municipal Board became Municipal Corporation in 1959.[158] Allahabad Cantonment has a cantonment board. The city of Prayagraj is currently divided into 80 wards,[159] with one member (or corporator) elected from each ward to form the municipal committee. The head of the corporation is the mayor, but, the executive and administration of the corporation are the responsibility of the municipal commissioner, who is an Uttar Pradesh government-appointed Provincial Civil Service officer of high seniority. The current mayor of Prayagraj is Abhilasha Gupta, whereas the current municipal commissioner is Avinash Singh.[160][161]

Prayagraj was declared to have metropolitan status in October 2006.[9] The metropolitan area is referred to in the 2011 Indian census and other official documents as Allhabad Urban Agglomeration. It consists of Prayagraj Municipal Corporation, three census towns (the cantonment, Arail Uparhar, and Chak Babura Alimabad), and 17 Outer Growth (OG) areas listed in the table below.[135]

Allahabad cantonment

[edit]Allahabad has a cantonment, which was set up in 1857, as part of a chain of cantonments setup across north and central India to consolidate British rule.[162] At that time, it comprised covering a total area of 4464.6939 acres including civil area of 142.7129 acres.[163]

This was in line with Allahabad being made the centre of the newly -created North-west Provinces, that year, with Delhi transferred to the Punjab province and the truncated province being ruled from Allahabad for the next 20 years.[164] Allahabad cantonment came under the new Cantonments Act of 1924, and post-independence under the Cantonments Act of 2006.[162] The cantonment was counted as part of the city in censuses until the 1931 Indian census, when it was started to be counted as a separate census town.

The 4th Infantry Division, also known as the Red Eagle Division, is headquartered at Allahabad cantonment.[165]

| Population of Allahabad Urban Agglomeration and its Parts According to Census Data for 1901–2011.[135] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | ||

| Prayagraj Urban Agglomeration | 172,032 | 171,697 | 157,220 | 183,914 | 260,630 | 332,295 | 430,730 | 513,036 | 650,070 | 844,546 | 1,042,229 | 1,212,395 | ||

| Prayagraj Municipal Corporation | 172,032 | 171,697 | 157,220 | 173,895 | 246,226 | 312,259 | 411,955 | 490,622 | 616,051 | 792,858 | 975,393 | 1,112,544 | ||

| Allahabad Cantonment (included in Allahabad in the 1901–1921 figures) |

12,487 | 11,996 | 11,615 | 10,019 | 14,404 | 20,036 | 17,529 | 20,591 | 30,442 | 38,060 | 24,137 | 26,944 | ||

| Arail Uparhar | 12,190 | |||||||||||||

| Chak Babura Alimabad | 4,876 | |||||||||||||

| Total of Allahabad Outer Growth (OG) areas listed below: | 1,246 | 1,823 | 3,577 | 13,628 | 42,699 | 55,841 | ||||||||

| Subedarganj Railway Colony (OG) | 1,246 | 1,823 | 3,577 | 3,606 | 872 | 1,568 | ||||||||

| Triveni Nagar (N.E.C.S.W.) (OG) | 4,125 | 1,732 | 3,515 | |||||||||||

| T.S.L. Factory (OG) | 466 | 317 | 753 | |||||||||||

| Mukta Vihar (OG) | 461 | 509 | 534 | |||||||||||

| Bharat Pump and Compressor Factory (OG) | 631 | 628 | 648 | |||||||||||

| A.D.A. Colony (OG) | 1,155 | 12,539 | 22,774 | |||||||||||

| Doorbani Nagar (OG) | 2,312 | 783 | 543 | |||||||||||

| ITI Factory and Res. Colony (OG) | 872 | 3,764 | 221 | |||||||||||

| Shiv Nagar (OG) | 990 | 1,449 | ||||||||||||

| Gurunanak Nagar (OG) | 867 | 947 | ||||||||||||

| Gandhi Nagar, Manas Nagar, Industrial Labour Colony (OG) | 5,319 | 6,313 | ||||||||||||

| Gangotri Nagar (OG) | 1,641 | 6,749 | ||||||||||||

| Mahewa West (OG) | 7,161 | 2,136 | ||||||||||||

| Begum Bazar (OG) | 514 | 841 | ||||||||||||

| Bhagal Purwa (OG) | 680 | 988 | ||||||||||||

| Kodra (OG) | 690 | 587 | ||||||||||||

| IOC Colony, Deoghat, ADA Colony and Jhalwagaon (OG) | 3,693 | 5,275 | ||||||||||||

Politics

[edit]Prayagraj is the seat of Allahabad High Court, the highest judicial body in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Prayagraj is known as the "Prime Minister Capital of India", since, seven of fifteen Indian prime ministers of India since independence have connections with the city (Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, Gulzarilal Nanda, Vishwanath Pratap Singh and Chandra Shekhar). All seven leaders were either born in Allahabad, were alumni of Allahabad University or were elected from an Allahabad constituency.[2] Prayagraj is administered by several government agencies. As the seat of the Government of Uttar Pradesh, Prayagraj is home to local governing agencies and the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly (housed in the Allahabad High Court building).[166] The Prayagraj district has two parliamentary constituency, namely, Prayagraj and Phulpur and elects 12 members of the legislative assembly (MLAs) to the state legislature.[167]

Central government offices/organisations

[edit]Prayagraj houses various central government offices and organisations, such as-

- Headquarters of Central Zonal Council

- Rapid Action Force (101 Battalion).

- Indo-Tibetan Border Police (Training Institute).

- Special officer for Linguistic Minorities (Regional Headquarters).

- Headquarters of Central Air Command.

- Services Selection Board (East Centre).

Ministry of Civil Aviation (India)

- Civil Aviation Training College.

- Headquarters of North Central Railway Zone.

- Headquarters of Central Organisation for Railway Electrification.

- Railway Recruitment Control Board (Selection Centre).

- Headquarters of Accountants General, Uttar Pradesh.

Ministry of Human Resource Development

- Central Board of Secondary Education (Regional office).

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

- Botanical Survey of India (Central Regional Centre, Allahabad).

- Centre for Social Forestry and Eco-Rehabilitation.

Ministry of Science and Technology (India)

- Harish Chandra Research Institute.

- Indian Institute of Geomagnetism (Regional Center).

- National Academy of Sciences, India.

Economy

[edit]Overall Prayagraj has a stable and diverse economy comprising various sectors such as State and Central government offices, education and research institutions, real estate, retail, banking, tourism and hospitality, agriculture-based industries, railways, transport and logistics, miscellaneous service sectors, and manufacturing. Average household income of the city is US$2,299.[168]

The construction sector is a major part of Prayagraj's economy.[169] Secondary manufacturers and services may be registered or unregistered;[170] according to the third All India Census for Small Scale Industries, there are more than 10,000 unregistered small-scale industries in the city.[171][172] An integrated industrial township has been proposed for 1,200 acres (490 ha) in Prayagraj by the Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India.[173]

The city is also home to glass and wire-based industry.[174] The main industrial areas of Prayagraj are Naini and Phulpur, where several public and private sector companies have offices and factories.[175] Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited, India's largest oil company (which is state-owned), is constructing a seven-million-tonnes-per-annum (MTPA) capacity refinery in Lohgara with an investment estimated at ₹62 billion.[176] Allahabad Bank, which began operations in 1865,[171] Bharat Pumps & Compressors and A. H. Wheeler and Company have their headquarters in the city. Major companies in the city are Reliance Industries, ITI Limited, BPCL, Dey's Medical, Food Corporation of India, Raymond Synthetics, Triveni Sheet Glass, Triveni Electroplast, EMC Power Ltd, Steel Authority of India, HCL Technologies, Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative (IFFCO), Vibgyor Laboratories, Geep Industries, Hindustan Cable, Indian Oil Corporation Ltd, Baidyanath Ayurved, Hindustan Laboratories.[177][178][179]

The primary economic sectors of the district are tourism, fishing and agriculture, and the city is a hub for India's agricultural industry.[180][181] In the case of agriculture crops, paddy has the largest share followed by bajra, arhar, urd and moong, in declining order during the Kharif season. In Rabi, wheat is predominant followed by pulses and oilseed. Among oilseed crops, mustard has very little area under pure farming and is grown mainly as a mixed crop. Linseed dominates the oilseed production of the district and is mainly grown in Jamunapar area. In the case of pulses, gram has the largest area followed by pea and lentil (masoor). There is fairly good acreage under barley.[182]

Transportation and utilities

[edit]

Air

[edit]The main international and domestic airport serving Prayagraj is Prayagraj Airport (IATA: IXD, ICAO: VEAB), which began operations in February 1966. The airport is 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from the city centre and lies in Bamrauli, Prayagraj. As of now, Prayagraj is connected to eleven cities by flight, where Air India's regional arm Alliance Air connects Prayagraj to Delhi and Bilaspur, while IndiGo connects it to Bangalore, Mumbai, Kolkata, Raipur, Bhopal, Bhubaneswar and Gorakhpur.[183][184] The nearest international airports are in Varanasi and Lucknow.[185]

The world's first airmail flight took place from Allahabad (Prayagraj) to Naini in February 1911, when 6,000 cards and letters where flown by French pilot Henri Pequet.[186]

Railways

[edit]Prayagraj Junction is one of the main railway junctions in northern India and headquarters of the North Central Railway Zone.[187]

Prayagraj has following nine railway stations in its city limits :[188]

| Station Name | Station Code | Railway Zone | Number of Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prayagraj Junction | PRYJ, formerly ALD | North Central Railway | 10 |

| Prayagraj Chheoki Junction railway station | PCOI, formerly ACOI | North Central Railway | 3 |

| Naini Railway Station | NYN | North Central Railway | 4 |

| Subedarganj railway station | SFG | North Central Railway | 3 |

| Prayag Junction railway station | PRG | Northern Railway | 3 |

| Prayagraj Sangam Railway Station | PYG | Northern Railway | 5 |

| Phaphamau Railway Station | PFM | Northern Railway | 3 |

| Prayagraj Rambagh railway station | PRRB, formerly ALY | North Eastern Railway | 5 |

| Jhusi Railway Station | JI | North Eastern Railway | 3 |

The city is connected to most other Uttar Pradesh cities and major Indian cities such as Kolkata, New Delhi, Hyderabad, Patna, Mumbai, Visakhapatnam, Chennai, Bangalore, Guwahati, Thiruvananthapuram, Pune, Bhopal, Kanpur, Lucknow and Jaipur.[189]

Roads

[edit]Buses operated by Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation and Prayagraj City Transport Service are an important means of public transport for travelling to various parts of the city, state and outskirts.[190] Auto Rickshaws have been a popular mode of transportation.[191] Cycle rickshaws are the most economical means of transportation in Prayagraj along with e-rickshaws.[191][192]

There are several important National Highways that pass through Prayagraj:[193]

| NH (acc. new numbering system) | NH (acc. old numbering system) | Route | Total Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH 19 | NH 2 | Delhi » Mathura » Agra » Kanpur » Prayagraj » Varanasi » Mohania » Barhi » Palsit » Dankuni (near Kolkata) | 2542 |

| NH 30 | NH 24B & NH 27 | Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand » Bareilly » Lucknow » Raebareli » Prayagraj » Rewa » Jabalpur » Raipur » Krishna District, Andhra Pradesh | 2022 |

| NH 35 | NH 76 & NH 76 Extension | Mahoba » Banda » Chitrakoot » Prayagraj » Mirzapur » Varanasi | 346 |

| NH 330 | NH 96 | Prayagraj » Pratapgarh » Sultanpur » Faizabad » Gonda » Balrampur | 263 |

Cable-stayed, New Yamuna Bridge (built 2001–04), is in Prayagraj and connects the city to the suburb of Naini across the Yamuna.[194] The Old Naini Bridge now accommodates railway and auto traffic.[195][196] A road bridge across the Ganges also connects Prayagraj and Jhusi.[197] National Waterway 1, the longest Waterway in India, connects Prayagraj and Haldia.[198]

The city generates 5,34,760 kg of domestic solid wastes daily, while the per capita generation of waste is 0.40 kg per day. The sewer service areas are divided into nine zones in the city.[23] Prayagraj Municipal Corporation oversees the solid waste management project.[199] Prayagraj was the first city to get pre-paid meters for electricity bill in Uttar Pradesh.[200][201] The city is equipped with over 40 CCTVs at major crossings and markets.[202]

Public health

[edit]

Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Uttar Pradesh oversees the healthcare system of Prayagraj. Its healthcare system comprises hospitals, medical facilities, private clinics and diagnostic centers. These facilities are either privately owned or owned and facilitated by the government. Prayagraj has a total of twenty four hospitals run by the administration.[203] Founded in memory of Pandit Motilal Nehru in 1961, Motilal Nehru Medical College (MLN Medical College and associated hospitals) is a government medical college in Prayagraj, with Swaroop Rani Nehru Hospital, Kamla Nehru Memorial Hospital, Sarojini Naidu Children's Hospital and Manohar Das Eye Hospital serving under its affiliation.[204] Some of the known multispecialty hospitals in and around Prayagraj are Alka Hospital, Swaroop Rani Nehru Hospital,[205] Amardeep Hospital, Asha Hospital, Ashutosh Hospital and Trauma Centre, Bhola Hospital, Dwarka Hospital, D R S Hospital, Jain Hospital, Parvati Hospital Pvt. Ltd., Phoenix Hospitals Pvt. Ltd., Priya Hospital, Sangam Multispeciality Hospital, Vatsalya Hospital, Yashlok Hospital and Research Centre, etc.[206]

Prayagraj healthcare also comprises many medical research institutes. The city also has diagnostic labs, clinics, consultation providers and pathological institutes like Kriti Scanning Centre,[207] Prayag Scan & Diagnostic Centre, and Sprint Medical.[208][209]

Smart city project

[edit]IBM selected Prayagraj among 16 other global cities for its smart cities programme to help it address challenges like waste management, disaster management, water management and citizen services.[210][211] The company commenced working on solid waste management and power sector in generating renewable energy.[212]

A memorandum of understanding was signed on 25 January 2015 between the United States Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) and the Government of Uttar Pradesh for developing Prayagraj as a smart city.[213][214] The pact came into existence after the bilateral meeting between the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the US President Barack Obama in October 2014, wherein it was announced that the US would assist India in developing three smart cities, Prayagraj, Ajmer and Visakhapatnam, in a boost to India's 100 smart city programme.[215] On 27 August 2015 the official list of 98 cities to be developed as smart cities, including Prayagraj, was announced by the Government of India.[216] Prayagraj Task Force was set up by the Minister of Urban Development Venkaiah Naidu which consists of the divisional commissioner as chairperson, secretaries of housing and urban planning and urban development in Government of Uttar Pradesh, the district magistrate and collector, the vice-chairperson of Prayagraj Development Authority and the mayor in addition to the Additional Secretary (Urban Development) in the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs and representatives of the Ministry of External Affairs and the USTDA.[217][218] The project is being assisted by the U.S.-India Business Council.[219]

As a part of Smart City Project, Civil Lines is being developed on the lines of Lucknow's Hazratganj. A sum of ₹20 crore (US$3,024,000) has been sanctioned to beautify all prominent crossings of the city. As per the plan, the administration proposed uniformity in signage and colour of buildings and a parking lot to be set up to solve traffic congestion.[220] A 1.35 km long riverfront along Yamuna river would be developed by the Prayagraj Development Authority, irrigation and power departments at a cost of ₹147.36 crore. The riverfront would be developed in two phases. In the first phase, around 650 metres at Arail would be developed along with the Yamuna, while in the second phase 700 metres of the stretch between New Yamuna Bridge and Boat Club in Kydganj would be taken up.[221]

Improving city libraries is part of the Smart City Mission. ₹6.6 crore is being spent improving and restoring Allahabad Government Public Library, which is in Chandra Shekhar Azad Park. The granite and sandstone building was founded in 1864 and was designed by Richard Roskell Bayne in the Scottish baronial style. Chandra Mohan Garg, CEO of Prayagraj Smart City, said: "we are undertaking the restoration of the building, for which we have engaged conservation architects; and preservation of manuscripts dating back over 400 years, and digitisation of all library services".[222]

Plans were announced in 2024 to set up "digital smart classrooms" in 48 government-ran primary schools within the city limits.[223]

Education

[edit]

The Prayagraj educational system is distinct from Uttar Pradesh's other cities, with an emphasis on broad education.[224] Board of High School and Intermediate Education Uttar Pradesh, the world's biggest examining body, is headquartered in the city.[225][226] Although English is the language of instruction in most private schools, government schools and colleges offer Hindi and English-medium education.[227] Schools in Prayagraj follow the 10+2+3 plan. After completing their secondary education, students typically enrol in higher secondary schools affiliated with the Uttar Pradesh Board of High School and Intermediate Education, the ICSE or the CBSE.[227] and focus on liberal arts, business or science. Vocational programs are also available.[228]

Prayagraj attracts students from throughout India. As of 2017, the city has one central university, two State Universities and an open university.[229] Allahabad University, founded in 1876, is the oldest university in the state.[229] Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology, Prayagraj is a noted technical institution.[230] Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences, founded in 1910, as "Agricultural Institute", is an autonomous Christian minority university in Prayagraj.[231] Other notable institutions in Allahabad include the Indian Institute of Information Technology – Allahabad; Motilal Nehru Medical College; Ewing Christian College; Harish-Chandra Research Institute; Govind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute; and Allahabad State University[232]

Culture

[edit]Although Hindu women have traditionally worn saris, the shalwar kameez and Western attire are gaining acceptance among younger women.[233] Western dress is worn more by men, although the dhoti and kurta are seen during festivals. The formal male sherwani is often worn with chooridar on festive occasions.[233] Diwali, Holi, Kumbh Mela, Eid al-Fitr and Vijayadasami are the most popular festivals in Prayagraj.[234]

Literature

[edit]

Prayagraj has a literary and artistic heritage; the former capital of the United Provinces, it was known as Prayag in the Vedas, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[235][236] Allahabad has been called the "literary capital of Uttar Pradesh",[237] attracting visitors from East Asia;[238] the Chinese travellers Faxian and Xuanzang found a flourishing city in the fifth and seventh centuries, respectively.[238][239] The number of foreign tourists, which mostly consisted of Asians, visiting the city was 98,167 in 2010 which subsequently increased to 1,07,141 in 2014.[240] The city has a tradition of political graffiti which includes limericks and caricatures.[90] In 1900, Saraswati, the first Hindi-language monthly magazine in India, was started by Chintamani Ghosh. Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, the doyen of modern Hindi literature, remained its editors from 1903 to 1920.[241] The Anand Bhavan, built during the 1930s as a new home for the Nehru family when the Swaraj Bhavan became the local Indian National Congress headquarters, has memorabilia from the Gandhi-Nehru family.[242]

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Hindi literature was modernised by authors such as Mahadevi Varma, Sumitranandan Pant, Suryakant Tripathi 'Nirala' and Harivansh Rai Bachchan.[243] A noted poet was Raghupati Sahay, better known as Firaq Gorakhpuri.[244] Gorakhpuri and Varma have received Jnanpith Awards.[245][246][247] Prayagraj is a publication centre for Hindi literature, including the Lok Bharti, Rajkamal and Neelabh. Persian and Urdu literature are also studied in the city.[248] Akbar Allahabadi is a noted modern Urdu poet, and Nooh Narwi, Tegh Allahabadi, Shabnam Naqvi and Rashid Allahabadi hail from Prayagraj.[249] English author and 1907 Nobel laureate Rudyard Kipling was an assistant editor and overseas correspondent for The Pioneer.[250]

Entertainment and recreation

[edit]Prayagraj is noted for historic, cultural and religious tourism. Historic sites include Alfred Park, the Victoria and Thornhill Mayne Memorials, Minto Park, Allahabad Fort, the Ashoka Pillar and Khusro Bagh. Religious attractions include the Kumbh Mela, the Triveni Sangam and All Saints Cathedral. The city hosts the Maha Kumbh Mela, the largest religious gathering in the world, every twelve years and the Ardh (half) Kumbh Mela every six years.[251][252] It also hosts a Magh Mela annually on the banks of the Triveni Sangam that typically lasts for one and a half months.[253][254] Cultural attractions include the Allahabad Museum, the Jawahar Planetarium and the University of Allahabad. North Central Zone Culture Centre, under the Ministry of Culture and Prayag Sangeet Samiti are nationally renowned centres of Arts, Dance, Music, local Folk Dance and Music, Plays/Theatre etc. and nurture upcoming artists. The city has also hosted the International Film Festival of Prayag.[255]

Media

[edit]The Leader and The Pioneer are two major English-language newspapers that are produced and published from the city.[256][257] All India Radio, the national, state-owned radio broadcaster, has AM radio stations in the city. Prayagraj has seven FM stations, including two AIR stations: Gyan Vani and Vividh Bharti, four private FM channels: BIG FM 92.7, Red FM 93.5, Fever 104 FM and Radio Tadka and one educational FM radio channel Radio Adan 90.4 run by Allahabad Agricultural Institute.[258][259] There is a Doordarshan Kendra in the city.[260] Regional TV channels are accessible via cable subscription, direct-broadcast satellite service or Internet-based television.[261]

Sports

[edit]Cricket and field hockey are the most popular sports in Prayagraj,[262] with kabaddi, kho-kho, gilli danda and pehlwani mostly being played in rural areas near the city.[263] Gully cricket, also known as street cricket, is popular among city youth.[262] The famous cricket club Allahabad Cricketers has produced many national and international cricket players. Several sports complexes are used by amateur and professional athletes; these include the Madan Mohan Malviya Stadium, the Amitabh Bachchan Sports Complex and the Boys' High School and College Gymnasium.[264] There is an international-level swimming complex in Georgetown.[265] The National Sports Academy in Jhalwa trains gymnasts for the Commonwealth Games. The Indira Marathon honours the late prime minister Indira Gandhi.[266][267][268]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]- Forest Research Centre for Eco-Rehabilitation

- Korrah Sadat, a village within Prayagraj Mandal

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mani, Rajiv (21 May 2014). "Sangam city, Allahabad". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ a b "City of Prime Ministers". Government of Uttar Pradesh. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Krishnaswamy & Ghosh 1935, pp. 698–699, 702–703.

- ^ a b c d e "Prayagraj City". allahabadmc.gov.in. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Poets' 'Allahabadi' Surnames Changed To 'Prayagraj' After UP Website Hack". NDTV.com. 29 December 2021.

- ^ a b "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Awadhi". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Metropolitan Cities of India" (PDF). cpcb.nic.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Six cities to get metropolitan status". The Times of India. 20 October 2006. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi (Benares). - ^ "Allahabad City Population Census 2011 | Uttar Pradesh". Census2011.co.in. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Allahabad Metropolitan Urban Region Population 2011 Census". Census2011.co.in. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "The world's fastest growing cities and urban areas from 2006 to 2020". City Mayors Statistics. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "10 Twin Towns and Sister Cities of Indian States". walkthroughindia.com. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Liveability Index". Institute for Competitiveness, India. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ a b Ujagir Singh (1958). Allahabad: a study in urban geography. Banaras Hindu University. pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Kama Maclean (2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0195338942. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ a b Pletcher, Kenneth (15 August 2010). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-61530-142-3. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ H.S. Bhatia (2008). Military History of British India: 1607–1947. Deep and Deep Publications'. p. 97. ISBN 978-81-8450-079-0. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b Ashutosh Joshi (2008). Town Planning Regeneration of Cities. New India Publishing. p. 237. ISBN 978-81-89422-82-0. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Kerry Ward (2009). Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ^ a b Akshayakumar Ramanlal Desai (1986). Violation of Democratic Rights in India. Popular Prakashan. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-86132-130-8. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ^ "With over 32 cr tourist arrivals in 9 months, UP turns top tourist destination". The Statesman. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b Mani, Rajiv (10 February 2011). "City generates 5,34,760 kg domestic waste daily". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Monier. "A Sanskrit–English Dictionary". www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ India Today Web Desk (15 October 2018). "Yogi Adityanath takes Allahabad to Prayagraj after 443 years: A recap of History". India Today. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ टाइम्स नाउ डिजिटल (16 October 2018). "क्या है प्रयागराज का मतलब? सृष्टि की रचना के बाद जहां ब्रह्मा ने सबसे पहले संपन्न किया था यज्ञ". Times Now (in Hindi). Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Akrita Reyar (17 October 2018). "What does 'Prayagraj' actually mean?". Times Now. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "History". Government of Uttar Pradesh. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ a b University of Allahabad Studies. University of Allahabad. 1962. p. 8.

- ^ Kama Maclean (2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0195338942. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Allahabad to Prayagraj: UP cabinet okays name change". India Today. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "UP Government Issues Notification Renaming Allahabad To Prayagraj". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Bhikkhu Nanamoli (Tr); Bhikkhu Bodhi(Tr) (1995). Teachings of The Buddha: Majjhima Nikaya. Simon and Schuster. p. 121. ISBN 978-0861710720.

- ^ Kane 1953, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (2013). India: A Sacred Geography. Three Rivers Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-385-53192-4. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Diane Eck (1981), India's "Tīrthas: "Crossings" in Sacred Geography, History of Religions, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 340–341 with footnote

- ^ a b Shiva Kumar Dubey (2001). Kumbh city Prayag. Centre for Cultural Resources and Training. pp. 31–41, 82. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Ludo Rocher (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

with footnotes

- ^ K. Krishnamoorthy (1991). A Critical Inventory of Rāmāyaṇa Studies in the World: Indian languages and English. Sahitya Academy. pp. 28–51. ISBN 978-81-7201-100-0. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ^ Rao, M. Subba. "Sachitra Shraman Bhagwan Mahavir".

- ^ a b c d e f Jinaprabhasuri, Acharya. "Vividh Tirthkalpa Sachitra".

- ^ a b c d e f www.wisdomlib.org (21 September 2017). "Part 12: Marudevī's omniscience and death". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Pedhi, Anandji Kalyanji. "Jain Tirth Sarva Sangraha Part 02".

- ^ a b Pedhi, Anandji Kalyanji. "Jain Tirth Sarva Sangraha Part 02".

- ^ Alexander Cunningham (1877). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol. 1. pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b c d John Irwin (1979). Herbert Hartel (ed.). South Asian Archaeology. D. Reimer Verlag (Berlin). pp. 313–340. ISBN 978-3-49600-1584. OCLC 8500702.

- ^ a b c d e f John Irwin (1983). "The ancient pillar-cult at Prayāga (Allahabad): its pre-Aśokan origins". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (2). Cambridge University Press: 253–280. JSTOR 25211537.

- ^ Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti (2001). Archaeological Geography of the Ganga Plain: The Lower and the Middle Ganga. Orient Blackswan. p. 263. ISBN 978-8178240169. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ a b Cunningham 1879, p. 39.

- ^ a b Krishnaswamy & Ghosh 1935, pp. 698–699.

- ^ Ujagir Singh (1958). Allahabad: a study in urban geography. Banaras Hindu University. p. 32.

- ^ Krishnaswamy & Ghosh 1935, pp. 698–703.

- ^ Krishnaswamy & Ghosh 1935, pp. 702–703.

- ^ Karel Werner (1990). Symbols in Art and Religion: The Indian and the Comparative Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-7007-0215-6. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Li Rongxi (1996), The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-886439-02-3, pp. 136–138

- ^ a b Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke (2010). "Review of Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 41 (1): 174–175. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Kama MacLean (2003). "Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbh Mela in Allahabad". The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (3): 877. doi:10.2307/3591863. JSTOR 3591863. S2CID 162404242.

- ^ K. A. Nilakanta Shastri, ed. (1978). A Comprehensive History of India, Volume 4, Part 2. Orient Longmans. p. 307.

- ^ Ujagir Singh (1958). Allahabad: a study in urban geography. Banaras Hindu University. pp. 29–30.

- ^ D. B. Dubey (2001). Prayāga, the Site of Kumbha Melā: In Temporal and Traditional Space. Aryan Books International. p. 57.

- ^ a b c R Burn (1907). "The Mints of the Mughal Emperors". Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Asiatic Society. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal: 78–79. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b Surendra Nath Sinha (1974). Subah of Allahabad under the great Mughals, 1580–1707. Jamia Millia Islamia. pp. 85–86.

with footnotes

- ^ Pandey, Vikas (7 November 2018). "Allahabad: The name change that killed my city's soul". BBC Home. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ Kama Maclean (2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954. Oxford University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-19-533894-2. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Surendra Nath Sinha (1974). Subah of Allahabad under the great Mughals, 1580–1707. Jamia Millia Islamia. pp. 25, 83–84.

- ^ a b Kama Maclean (2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-533894-2. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Abraham Eraly (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-14-100143-2. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ John F. Richards (1995). The Mughal Empire, Part 1, Volume 5. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1964). The History of India, 1000 A.D.-1707 A.D. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 587.

- ^ Abdul Karim (1995). History of Bengal: The Reigns of Shah Jahan and Aurangzib. Institute of Bangladesh Studies, University of Rajshahi. p. 305.

- ^ Kama Maclean (2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-533894-2. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ A. C. Banerjee; D. K. Ghose, eds. (1978). A Comprehensive History of India: Volume Nine (1712–1772). Indian History Congress, Orient Longman. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (1998). Anglo-Maratha relations during the administration of Warren Hastings 1772–1785, Volume 1. Popular Prakashan. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-8171545780. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Barbara N. Ramusack (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-139-44908-3. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Barbara N. Ramusack (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-139-44908-3. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Hayden J. Bellenoit (2017). The Formation of the Colonial State in India: Scribes, Paper and Taxes, 1760–1860. Taylor & Francis. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-134-49429-3. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018.

- ^ Visalakshi Menon (2003). From Movement To Government: The Congress in the United Provinces, 1937–42. SAGE Publications. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-7619-9620-0. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ^ Sugata Bose; Ayesha Jalal (2004) [1997]. Modern South Asia: History, Culture and Political Economy (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-415-30786-4. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ^ Edward John Thompson; Geoffrey Theodore Garratt (1962). Rise and Fulfilment of British rule in India. Central Book Depot. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2014.