Philip DeFranco

| Philip DeFranco | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

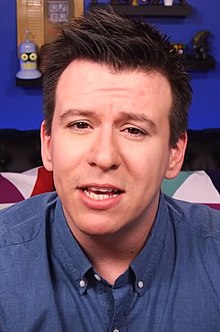

DeFranco in 2018 | ||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||

| Born | Philip James Franchini Jr. December 1, 1985 New York City, U.S. | |||||||||

| Nationality | American | |||||||||

| Occupation |

| |||||||||

| Spouse |

Lindsay Doty (m. 2015) | |||||||||

| Children | 2 | |||||||||

| Website | beautifulbastard | |||||||||

| YouTube information | ||||||||||

| Channels | ||||||||||

| Years active | 2006–present | |||||||||

| Genres |

| |||||||||

| Subscribers |

| |||||||||

| Total views |

| |||||||||

| Network | Revision3 / Discovery Digital Networks (2012–2017) Rogue Rocket (2018–present) | |||||||||

| Associated acts | SourceFed | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Last updated: October 12, 2023[1][2] | ||||||||||

Philip James DeFranco[3] (born Philip James Franchini Jr.;[4] born December 1, 1985), commonly known by his online nickname PhillyD, and formerly known as sxephil, is an American media host and YouTube personality. He is best known for The Philip DeFranco Show, a news commentary show centered on current events in politics and pop culture.

DeFranco has also been involved in the creation of other successful channels on YouTube, including personal vlog channel Philly D, the YouTube Original news channel SourceFed and its nerd culture spinoff SourceFed Nerd, gaming channel Super Panic Frenzy, and family vlogging channel TheDeFrancoFam. His primary channel has accumulated over 6.5 million subscribers and 1.5 billion views, as of January 2024. Over his decade-long YouTube career, he has been cited as a pioneer of YouTube and news coverage online, and has won various awards for his online content.

Early life

[edit]DeFranco was born Philip James Franchini Jr. in The Bronx, New York City, New York.[3][5][6] He is of Italian descent.[4] He has a stepmother who works at a car dealership.[7]

He was a student at the University of South Florida (USF),[8] a biology student at Asheville–Buncombe Technical Community College,[9][10] and later a junior at East Carolina University.[11] In 2007, DeFranco lived in Tampa, Florida, and later Atlanta, Georgia.[11] Once in Florida, he used his USF student loan to purchase a computer and camera.[12][13][8] He worked as a waiter in a number of restaurants while making videos in 2007.[14]

DeFranco lived in a car until moving back with his father in Tampa, Florida, on condition that he would return to college, which he ultimately did not do.[15]

DeFranco was raised Catholic but later identified as atheist.[16]

YouTube

[edit]2006–2011: Early years

[edit]Launching The Philip DeFranco Show

[edit]

On September 15, 2006,[17] DeFranco created his YouTube account during his finals at East Carolina University, originally registered as "sxephil", in which he talks about "newsie type stuff, and things that matter to [him] today."[15][18] DeFranco has cited his early influences as Ze Frank, Dane Cook, and the Vlogbrothers.[19][20] Early on, he began calling his news-centered videos The Philip DeFranco Show.[15] All of his sxephil videos from before March 13, 2017, have been made private or deleted from the channel.

Before the YouTube partner program was available, he asked for donations from his viewers after claiming to have run out of money, and selling everything except his Mac, camera, and clothes, and overdrawing his bank account so he could spend a night in a hotel as he found it too scary sleeping in a car in Brooklyn.[21]

An online viewer census from 2007 showed that one-third of his viewers were 16- and 17-year-old girls.[9] In the same year, DeFranco opened his second YouTube channel, "PhilipDeFranco", which includes a series of vlogs which he calls "The Vloggity".[22] He streamed on BlogTV twice a week and took a cut of the revenue which was up to $12 CPMs.[23]

In August 2007, DeFranco conducted an experiment by uploading a video titled "Big Boobs and You". The video's thumbnail image was what the title described, except that the image only flashed for a split second. The rest of the video's content was DeFranco talking. It quickly became his most successful video at the time, with 1.8 million views. From then on he changed his content to sex, gossip, and news.[24] In 2012, YouTube redesigned their website, as videos with cleavage thumbnails attracted many clicks but were abandoned instead of being watched.[25]

Fan-voting competitions and Hooking Up

[edit]DeFranco used his large audience to win the Spore Creature Creator, a game promotion competition, and in doing so beat celebrities such as Stan Lee, Katy Perry, and Elijah Wood.[26] The winner's prize was to choose which charity would receive a donation of $15,000. He chose the PKD Foundation,[27] an organization dedicated to fighting polycystic kidney disease (PKD), which he attributed to his family's history with the condition.[11] DeFranco's large online audience also enabled him to win Wired's Sexiest Geek of 2008 competition, a reader-voted contest.[28]

In October 2008, DeFranco co-starred with Jessica Rose and Kevin Wu in Hooking Up, written and directed by Woody Tondorf as a promo for HBOLabs (the online arm of HBO). Hooking Up is a scripted 10-episode web series set at a fictional university where the students spend most of their time emailing and using Facebook, but still manage to miscommunicate.[29][30] Guest appearances on Hooking Up were made by Kevin Nalty, Michael Buckley, and other popular Internet celebrities.[31]

By the show's second day on YouTube, it had received more than 450,000 views.[32][33] Bobbie Johnson of The Guardian said that many Web surfers have "scoffed at what they see as a cynical attempt to cash in."[34]

In 2008, he stated in an interview that his listed salary of $250,000 from a number of sources on the Internet, including and beyond YouTube, was initially a joke, but would become accurate.[11][35] He has been paid by companies to create videos to promote Carl's Jr.'s burgers,[36] and the US television series Lie to Me and Fringe.[37]

The Station, Like Totally Awesome, and other projects

[edit]DeFranco was a founding member of The Station, but left only a few months after it was created.[38] DeFranco's early attempts at launching channels with scopes outside of his eponymous news series included BamBamKaboosh and TheDeFrancoUpdate.[39] DeFranco also launched Like Totally Awesome (LTA), in which video reviews of a movie, video game, or technology were submitted by viewers and compiled into an episode of a video series called The Quad.[40] The show was run by Sarah Penna, the creator of the YouTube multi-channel network Big Frame.[41] Early in his YouTube career, Penna aided DeFranco, securing him coverage in news articles and magazines, such as Fast Company. One of those articles mentioned that DeFranco frequently collaborated with the advertising agency, Mekanism.[42][43]

DeFranco entered the 2010s having his "sxephil" channel as the fifth-most subscribed on the platform.[44] In July 2010, DeFranco attended the first VidCon event, where he was a speaker.[45] Also in the month, DeFranco co-created CuteWinFail, along with Toby Turner; the online series was described by Fruzsina Eördögh of ReadWrite as "essentially the YouTube equivalent of America's Funniest Home Videos."[46] DeFranco launched a merchandise line called ForHumanPeoples in 2011.[47]

2012–2017: SourceFed and Discovery/Group Nine years

[edit]Launching SourceFed

[edit]

In January 2012, DeFranco launched SourceFed, which at the time was produced by James Haffner.[48][49][50] This came around the same time in which DeFranco signed with Revision3, a multi-channel network.[51][52][53] In February, DeFranco stated he paid himself $100,000 a year, and reinvests the rest back into his company.[38][54]

Later in the year, DeFranco hosted the 25th anniversary of Discovery Channel's Shark Week.[53][55][56][57]

DeFranco, along with SourceFed co-hosts Elliott Morgan and Meg Turney, joined journalists at the 2012 Republican National Convention and the Democratic National Convention as part of YouTube's "Elections Hub".[15][58][59] The Philip DeFranco Show and SourceFed were nominated for awards in the 3rd installment of the Streamy Awards.[60]

In September, it was reported that DeFranco received almost 30 million views a month,[55] while by October, his channel was noted to have accumulated 2 million subscribers.[53] The Philip DeFranco Show and SourceFed were nominated for Streamy Awards; The PDS was nominated for Best First-Person Series and Best News and Culture Series. SourceFed was also nominated for Best News and Culture Series, as well as Best Live Series and its "#PDSLive 2012 Election Night Coverage" program was nominated for Best Live Event.[60]

In January 2013, DeFranco took part in a Google+ Hangout with United States Vice President Joe Biden and Guy Kawasaki, discussing gun laws.[61][62] In February, DeFranco was a featured as a guest judge on the second season of Internet Icon.[63]

Expanding his network

[edit]Later, in May, SourceFed Nerd, a branch of SourceFed, was launched.[64] In the same month, DeFranco's assets, including The Philip DeFranco Show and SourceFed, were acquired by Revision3, which itself was a subsidiary of Discovery Digital Networks.[65][66] Upon the acquisition, DeFranco became added as an exec of Revision3, the Senior VP of a new Revision3 subsidiary, Phil DeFranco Networks and Merchandise.[67][68] In October, as part of his new network, DeFranco launched the ForHumanPeoples channel, based on his clothing and merchandise line.[69] In November 2013, DeFranco was a special guest in a live pre-show simulcast for the Doctor Who 50th anniversary from YouTube Space LA.[70] Additionally, DeFranco has organized live shows and meetup events in locations such as Arizona, Los Angeles, and Toronto.[71][72][73]

DeFranco aspired to have launched channels within his network by the end of 2013, though due to "the logistical complications of joining Discovery, adding staff and strategizing the future," those plans did not materialize.[74] DeFranco later planned 2014 to be the year that he would begin launching new channels.[74] These plans once again fell through, but in 2015, DeFranco was involved in the launching of Super Panic Frenzy, a gaming network, including a YouTube channel and a Twitch live-stream show.[75][76]

2017–present: Independent content creation

[edit]DeFranco Elite and 2017 coverage

[edit]In 2017, DeFranco announced he was no longer working with Group Nine Media and would instead be an independent creator again.[77] In addition to this, DeFranco announced the launch of DeFranco Elite, a crowdfunding initiative on Patreon; DeFranco Elite functioned as a way for fans to help fund The Philip DeFranco Show, which DeFranco stated would help avoid the series' funding to be tied to YouTube ad revenue.[78] By the end of the year, The Outline noted that DeFranco had over 13,000 Patreon subscribers donating an amount of money that while undisclosed was enough to rank him within the platform's top 20 creators.[79] In 2019, DeFranco was earning approximately $50,000 a month from Patreon.[80]

DeFranco's coverage of issues concerning YouTube culture—such as PewDiePie's alleged anti-Semitism controversy and the DaddyOFive child abuse story—were among those most cited by online and mainstream media publications.[81][82][83] In his stories covering the DaddyOFive channel, DeFranco highlighted the channel's creators Mike and Heather Martin, and the abuse they inflicted on their children in videos posted on the channel.[82][84] DeFranco's coverage and criticism of the channel sparked a community backlash and heightened media attention that led to the Martins losing custody of two of their children,[82] and ultimately being charged with and found guilty of child neglect.[84][85]

Another topic DeFranco was noted by media publications for covering in 2017, was that of demonetization of YouTube creators.[86][87] DeFranco continued to be frequently cited as critical of the platform, regarding issues involving ad revenue and demonetization, with noted criticism of ads being allowed on the YouTube channels of mainstream talk shows but not on those of native creators.[83][88] Due to hot-button topics that can arise when delivering the news, DeFranco's content is particularly prone to being deemed "unfriendly" to advertisers.[89]

In June 2017, DeFranco's channel was cited by The Verge as having over 5.4 million subscribers.[90] DeFranco's subscriber growth slowed down in 2017, although his channel's monthly views continued to yield growing numbers.[91]

BetterHelp controversy

[edit]In October 2018, BetterHelp gained attention from YouTube personalities after concerns were raised about alleged use of unfair pricing, paid reviews from actors, and questionable terms of service.[92] Along with creators like Shane Dawson, DeFranco faced backlash for being among their most high-profile supporters. Both DeFranco and BetterHelp CEO Alon Matas addressed the issue, giving statements to Polygon's Julia Alexander.[93] On October 15, DeFranco tweeted that he had formally ended his relationship with BetterHelp.[94]

Launching Rogue Rocket

[edit]DeFranco launched Beautiful Bastard in February 2019, a line of hair care named after his catchphrase from the introductions of his news show.[95]

Since regaining control over his properties from the Discovery Network in May 2017, DeFranco has been working towards broadening his content and reach. He began work on Rogue Rocket and would launch the news network on April 22, 2019.[96] The network's launch was accompanied by a website.[96] A YouTube channel for the network, produced by Amanda Morones and featuring news story breakdowns launched in July; these breakdowns are presented in longer formats (such as 10- to 30-minute mini-documentaries) than those seen on The Philip DeFranco Show.[97] Instead of being hosted by DeFranco, the channel features an on-camera cast of correspondents; the first of these correspondents was Maria Sosyan.[97] In addition to the website and YouTube channel, the Rogue Rocket network also comprised a podcast named A Conversation With, in which DeFranco hosts and interviews a subject.[98]

In 2020, YouTube tapped various YouTubers, with DeFranco amongst them, to interview Anthony Fauci, with the goal of bringing information related to the COVID-19 pandemic to younger audiences.[99][100]

Public image and influence

[edit]

Due to joining YouTube in 2006 and soon gaining a sizable audience on the website, DeFranco has been cited as a pioneer of both YouTube and new media, in general.[89] Lucas Shaw of TheWrap described DeFranco as "one of the first video bloggers to find success on YouTube, and has since built", as well as having an, "entrepreneurial spirit and understanding of YouTube".[74] DeFranco was described by The Washington Post as part of the first generation of YouTube's creators, with the publication writing, "there are the originals, the older ones who became famous on YouTube when the only sort of Internet fame that existed was random viral stardom: Phil DeFranco, Jenna Marbles and Hannah Hart, for instance."[101]

The Los Angeles Times has described DeFranco as, "the Walter Cronkite for the YouTube generation who generates hundreds of headlines in under 10 minutes".[102] Sarah Kessler of Fast Company has referred to DeFranco as his generation's "Jon Stewart, if not Rupert Murdoch and News Corp".[103] HuffPost has also likened DeFranco to Stewart, as well as Stephen Colbert and Bill Maher, commending DeFranco's ability to balance "important, controversial, and potentially dry topics" with pop culture stories.[53]

David Cornell of The Inquisitr News wrote that DeFranco is "one of the leading sources of news" on YouTube and one of the platform's success stories.[104] Julia Alexander of The Verge has similarly described DeFranco as "one of the most notable voices on the site,"[83] while the publication's Lizzie Plaugic described DeFranco's content as being more akin to that of a gossip or tabloid outlet. Plaugic wrote "the biggest differentiators of gossip channels are the hosts. Philip DeFranco tries to position himself as an objective, buttoned-up talk show host, even though his eponymous show is all about his take on the biggest names in YouTube drama."[90]

DeFranco's ventures in creating an online media network have also been noted. Alex Iansiti of Huffington Post (now HuffPost) noted, "The Philip DeFranco Show is a great example of a media company to sprout out of YouTube".[105] Variety similarly expressed that DeFranco has "built upon a cult following and turned his YouTube show into a bonafide media empire."[106]

Views

[edit]Politics

[edit]Politically, DeFranco has described himself as "fiscally conservative, socially liberal, for the most part."[107] He expresses support for LGBT rights, including gay marriage and transgender identity, but he holds conservative views on company taxation.[108] While on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast, DeFranco stated that prior to moving to California he was "ultra-liberal".[109] Starting a business there caused him to lean more center.[109] He voted for Libertarian nominee Gary Johnson in the 2012 United States presidential election, but he no longer labels himself a libertarian.[110] DeFranco has criticized the perceived authoritarian nature as well as Twitter activity of former U.S. president Donald Trump.[108]

Media, news, and reporting

[edit]DeFranco has noted he likes to verify the news he covers and comments on, stating "I have to see several news sources that I trust."[19] On this, Polygon has stated that DeFranco expressed paranoia relating to the need to ensure that stories are completely correct.[111] DeFranco also likes to incorporate a "human side to every story,"[19] and has been known to specifically highlight optimistic or feel-good stories to counter the typical grittiness of a news cycle.[111] When covering shootings, DeFranco only reports on known facts at the time and has a policy to not use the perpetrator's name or image.[112]

Following PewDiePie's December 2019 announcement that he would be taking a break from posting on YouTube, CNN published an article about PewDiePie, focusing on his past controversies; DeFranco cited this CNN article when he addressed what he referred to as a "crisis of credibility problem" for mainstream media outlets.[113]

YouTube

[edit]Beginning in 2016, DeFranco became notably critical of YouTube's advertising policies, as they would begin to result in widespread demonetization–a term describing an incident in which something triggered YouTube's system to remove advertisements from a video–for creators across the platform.[114][115][116] DeFranco's criticism of YouTube regarding this topic would continue in the following years.[117]

Dating as far back as 2008, DeFranco has been frequently cited as pondering a potential end to his eponymous news series or an exit from the platform altogether.[11][118][119][120] DeFranco's reasons for this have varied from a personal want to "not overrun [his] time" to being frustrated with the platform's unstable revenue source.[11][120] In April 2018, DeFranco again expressed frustrations with the YouTube platform and detailed his progress on developing a network; he hired a six-person research and investigative team, curated hosts for short- and long-form content, and tested a morning podcast, among other things in preparation for the network's launch.[121] Months later while at VidCon, he stated that he saw himself walking from hosting the PDS within three years, saying "I don't know how to do the show I'm doing now in three years without phoning it in." He also added that he would remain online in some capacity, expressing, "in some way, I will always want to make a show and have that interaction, and I think that will evolve."[111]

Personal life

[edit]DeFranco has polycystic kidney disease which he inherited from his father and grandfather.[11] He has a younger sister named Sabrina.[122]

As of 2020, DeFranco lives in Encino, Los Angeles, with his wife, media literacy and mental health advocate Lindsay Jordan DeFranco (née Doty), and their two sons. DeFranco proposed to Doty, then his longtime girlfriend, on August 16, 2013, at his "DeFranco Loves Dat AZ" show in Tempe, Arizona.[123][124] Their first son, named Philip James "Trey" DeFranco III, was born in 2014.[125] The couple married on March 7, 2015, and it was captured on social media.[126][127] Their second son, Carter William DeFranco, was born in 2017.[128] In 2019, Lindsay launched Not So Fast, a media literacy campaign.[112] The couple moved into their Encino home in late 2019 after previously living in San Fernando and Sherman Oaks.[106]

Filmography

[edit]| Year(s) | Title | Role | Episodes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007–present | The Philip DeFranco Show | Host | All, main role | |

| 2008 | Hooking Up | Nick | All, main role | [29] |

| 2013 | Internet Icon | Guest judge | 1 | [63] |

| 2018 | Hot Ones | Himself | 1 | [129] |

| 2019 | Gochi Gang | Himself | 1 | [130] |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Work | Category | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Philip DeFranco | Sexiest Geek | Wired magazine | Won | [28] |

| 2010 | Best Vlogger | 2nd Streamy Awards | Nominated | [131] | |

| 2013 | The Philip DeFranco Show | Best News Series | 2nd IAWTV Awards | Won | [132] |

| Best Writing (Non-Fiction) | Nominated | [133] | |||

| Best First-Person Series | 3rd Streamy Awards | Nominated | [60] | ||

| Best News and Culture Series | Won | [60] | |||

| SourceFed | Nominated | [60] | |||

| Audience Choice for Best Series of the Year | Won | [60] | |||

| Best Live Series | Nominated | [60] | |||

| SourceFed:#PDSLive 2012 Election Night Coverage | Best Live Event | Nominated | [60] | ||

| 2014 | The Philip DeFranco Show | Audience Choice for Best Show of the Year | 4th Streamy Awards | Nominated | [134] |

| SourceFed | News and Current Events | Won | [134] | ||

| Audience Choice for Best Show of the Year | Nominated | [134] | |||

| SourceFed Nerd | Gaming | Nominated | [134] | ||

| 2015 | The Philip DeFranco Show | Best News and Culture Series | 5th Streamy Awards | Nominated | [135] |

| Audience Choice for Best Show of the Year | Nominated | [135] | |||

| 2016 | Best News and Culture Series | 6th Streamy Awards | Won | [136] | |

| Audience Choice for Best Show of the Year | Won | [136] | |||

| 2017 | Best News and Culture Series | 7th Streamy Awards | Nominated | [137] | |

| Audience Choice for Best Show of the Year | Nominated | [138] | |||

| 2018 | Best News and Culture Series | 8th Streamy Awards | Won | [139] | |

| Audience Choice for Best Show of the Year | Nominated | [139] | |||

| 2019 | News | 9th Streamy Awards | Won | [140] | |

| Show of the Year | Nominated | [140] | |||

| 2020 | News | 10th Streamy Awards | Nominated | [141] | |

| 2021 | 11th Streamy Awards | Nominated | [142] | ||

| 2022 | 12th Streamy Awards | Nominated | [143] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Philip DeFranco's YouTube Stats (Summary Profile)". Social Blade. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Philly D's YouTube Stats (Summary Profile)". Social Blade. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b DeFranco, Philip (August 20, 2016), This is a Secret I've Had for 10 Years. It's time you know…, retrieved August 22, 2016

- ^ a b DeFranco, Philip (August 28, 2012). "Also for the 3 of you freaking out that my real last name isn't DeFranco; it essentially is". Facebook. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

DeFranco is what I started telling people when they kept butchering my real last name which is Franchini pronounced Fran-keeny.

- ^ "About PhillyD.tv". Archived from the original on April 12, 2009.

- ^ "Philip DeFranco about". Facebook.com. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip (January 31, 2012). Whats New, PKD, and Things n Stuff.

my stepmum for the longest time ever to come out here for .. she works for a car dealership

- ^ a b Rampbell, Catherine (September 10, 2007). "YouTubers Try a Different Forum: Real Life". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Ratner, Andrew (September 23, 2007). "For 1 college video blogger, it's a really strange trip". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip. "sXePhil – MySpace". Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Powers, Nicole (December 31, 2008). "Philip DeFranco is sxephil". SuicideGirls. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip. "This video hurts my soul. There is a difference". Archived from the original on November 28, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip. "An update on the Book". Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Philly D. (sXePhil) (July 3, 2007). "Cool Stuff: Filed Under (Uncategorized)". PhillyD.tv. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Chmielewski, Dawn C. (August 28, 2012). "YouTube gives wacky anchorman Philip DeFranco greater exposure". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ "IDIOT ROBBER SHOT. THEN IT GETS EVEN FUNNIER". YouTube. December 3, 2013. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Philip DeFranco – YouTube about page". YouTube. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Eigenheer, Michelle (September 11, 2012). "Webshows that make you smarter". The Louisville Cardinal. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c Humphrey, Michael (August 26, 2015). "Philip DeFranco: YouTube's Original Everyman Is Growing On His Terms". Forbes. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip (November 3, 2008). End of the Road For Me. The Philip DeFranco Show. YouTube. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

"When I started this show, I was inspired by great people. Like Ze Frank or the Vlogbrothers, and knowing I could never be as good as them, I did my own thing.

- ^ "PhillyD.tv". Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Trachtenberg, Lance (June 1, 2012). "The Vloggity: Intelligent Venting". Placevine. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "BlogTV's YouTube Stars Making Real Money, Company Isn't". 22 October 2008. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Sarno, David (October 14, 2007). "The bait is sexy; be prepared for a switch". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ "YouTube Now: Why We Focus on Watch Time".

- ^ Terdiman, Daniel (September 2, 2008). "Celebrities get their chance to make 'Spore' creatures". CNET. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Polycystic kidney disease | PKD Foundation". PKD Foundation. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Wallace, Lewis (December 31, 2008). "Sexiest Geeks of 2008, as Voted by Wired.com Readers". Wired. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Hustvedt, Marc (September 8, 2008). "HBO's Latest Experiment: 'Hooking Up' YouTube Stars To Make A Web Series". Tubefilter. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Wallenstein, Andrew (September 8, 2008). "HBO offshoot launches Web video series". Reuters. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ Learmonth, Michael (September 8, 2008). "Looking For An Online Hit, HBO Tries A Bunch Of YouTube Cewebrities". Silicon Alley Insider. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ "NTV Rerun: What Constitutes an Online Hit?". GigaOM. September 24, 2008. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Russo, Maria (October 3, 2008). "Hooking Up: When YouTube stars get all cleaned up?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Bobbie (October 6, 2008). "The rise and rise of the YouTube generation, and how adults can help". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Burns, Kelli S. (2009). Celeb 2.0: How Social Media Foster Our Fascination with Popular Culture. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-313-35689-6.

- ^ Burkitt, Laurie (August 24, 2009). "Brands Flock to Niche Video Networks". Forbes.

- ^ "Hitviews Tapped by FOX to Market 'Fringe' and 'Lie to Me'". PR Newswire. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Cohen, Joshua (February 10, 2012). "Phil DeFranco Pays Himself $100K a Year". Tubefilter. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ "Shay Carl, Philip DeFranco and Kassem G Sound Off On Ray William Johnson Controversy Via Twitter". NewMediaRockstars. December 12, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Liz Shannon (January 13, 2010). "Philip DeFranco Brings Together Aspiring YouTubers for Like Totally Awesome". GigaOM. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Eördögh, Fruzsina (July 18, 2012). "Sarah Penna: The Most Influential New Media Entrepreneur You've Never Heard Of". ReadWrite. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Laporte, Nicole (March 18, 2013). "How Digital Agent Sarah Penna Makes Hollywood and YouTube Click". Fast Company. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Borden, Mark (May 1, 2010). "The Mekanism Guarantee: They Engineer Virality". Fast Company. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Leskin, Paige (December 31, 2019). "The 10 most popular YouTubers at the beginning of the decade — and where they are now". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Liz Shannon (July 5, 2010). "VidCon 2010 Promises a Celebration of Online Video". Gigaom. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Eördögh, Fruzsina (December 6, 2012). "Web Celebrity Toby Turner Fired From His Own Show: Has YouTube Gone Corporate?". ReadWrite. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (October 9, 2013). "Philip Defranco Debuts ForHumanPeoples Channel To Showcase Cool Stuff". Tubefilter. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Newton, Casey (February 6, 2012). "YouTube's Phil DeFranco building an empire". The Technology Chronicles. San Francisco Gate. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ "Philip DeFranco's latest YouTube venture is a hit". Daily Dot. January 30, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ Eördögh, Fruzsina (August 2, 2012). "YouTube Premium Channel SourceFed Racks Up 500,000 Subscribers". Readwrite. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ Baldwin, Drew (January 6, 2012). "Exclusive: Revision3 Exec On Signing Philip DeFranco". Tubefilter. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Wallenstein, Andrew (January 5, 2012). "Revision3 signs Philip DeFranco". Variety. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Shapiro, Evan (October 2, 2012). "We Have Watched 2,100 Years of 'Gangnam Style'". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ^ Zeplin, Philip (July 2, 2013). "How much money does YouTubers make?". Novel Concept. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Mahoney, Sarah (September 28, 2012). "Can One TV Brand Reach 10 Billion Devices?". MediaPost. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ Holbrook, Damian (August 16, 2012). "Phil DeFranco Bites Into Shark Week". TV Guide. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Newsome, Brad (December 6, 2012). "Pay TV: Thursday, December 6". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ Perigard, Mark (August 24, 2012). "YouTube launches 'hub' dedicated to 'round-the clock campaign coverage". Boston Herald. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Meredith, Leslie (August 23, 2012). "YouTube launches 2012 elections hub". Fox News. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "3rd Annual Nominess". Streamys. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Raghavan, Ramya (January 23, 2013). "Fireside Hangouts: Join Vice President Biden in a discussion about gun violence". Google Official Blog. Blogspot. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ White House Hangout with Vice President Joe Biden on Reducing Gun Violence. Obama White House. YouTube. January 24, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Lanning, Carly (February 12, 2013). "Ryan Higa On 'Internet Icon' Season Two and Being YouTube's #3 Most Subscribed [Interview]". New Media Rockstars. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ Cohen, Joshua (May 16, 2013). "SourceFed Launches Spinoff YouTube Channel, SourceFed Nerd". Tubefilter. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (May 30, 2013). "Discovery's Revision3 Snaps Up Phil DeFranco's YouTube Network". Variety. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (July 31, 2013). "Phil DeFranco Was Ready to Give Up on YouTube – Until Google Gave Him Money". TheWrap. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (May 30, 2013). "Revision3 Acquires Philip DeFranco's Assets, Adds DeFranco As Exec". Tubefilter. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Millar, DiAngelea (May 30, 2013). "Philip DeFranco goes from Web host to network exec". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (October 9, 2013). "Philip DeFranco Debuts ForHumanPeoples Channel To Showcase Cool Stuff". Tubefilter. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (November 19, 2013). "BBC America Slates 'Doctor Who' YouTube Live Simulcast to Promote 50th Anniversary Show". Variety. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (August 7, 2013). "Phil DeFranco Headed To Phoenix, Arizona For Live Show". Tubefilter. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (October 1, 2014). "Vimeo On Demand Offers Philip DeFranco's Los Angeles Live Show". Tubefilter. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Garwol, Deanna (October 23, 2014). "A fan meets her favorite YouTube star". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Shaw, Lucas (October 10, 2013). "YouTube Pioneer Phil DeFranco to Launch First New Channel for Discovery (Exclusive)". TheWrap. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Molly (March 20, 2015). "Amazon's Twitch adding Discovery's 'Super Panic Frenzy' gaming platform Monday". GeekWire. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Brouwer, Bree (March 16, 2015). "Discovery Debuts Gaming Network Super Panic Frenzy, Hosts Launch Giveaway". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip (May 1, 2017). It's Time For You To Know... Philip DeFranco. YouTube. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (May 1, 2017). "YouTube Star Philip DeFranco Splits With Group Nine Media, Launches Crowdfunded News Network". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ Knepper, Brent (December 7, 2017). "No one makes a living on Patreon". The Outline. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (June 25, 2019). "YouTube looks to demonetization as punishment for major creators, but it doesn't work". The Verge. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Thorne, Will (February 17, 2017). "Prominent YouTubers Rally Around PewDiePie in Anti-Semitism Saga". Variety. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Soteriou, Stephanie (May 3, 2017). "YouTubers lose custody of children after Philip DeFranco highlights abuse in their videos". Yahoo! News. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Julia (October 10, 2017). "YouTube fixing monetization issues with 'premium tier' partners after complaints". Polygon. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Weiss, Geoff (August 11, 2017). "Parents Behind DaddyOFive Charged With 2 Counts Of Child Neglect". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Augenstein, Neil (September 11, 2017). "'DaddyOFive' parents found guilty of neglect, avoid jail". WTOP News. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (October 27, 2017). "YouTube rolls out first update to fix major demonetization problems". Polygon. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Tamburro, Paul (October 9, 2017). "YouTube Branded Hypocritical For Valuing Celebrities Over Creators". Game Revolution. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (June 6, 2017). "Philip DeFranco Calls Out What He Sees As YouTube's Ad Double Standard, Vows To Take Next Show Elsewhere". Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Weiss, Geoff (June 24, 2017). "Hank Green, Philip DeFranco Discuss Adpocalypse And Aging During VidCon One-On-One". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Plaugic, Lizzie (June 7, 2017). "YouTube's gossip vloggers have created their own tabloid industry". The Verge. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Ghosh, Shona (December 31, 2017). "The world's biggest YouTube stars are seeing a massive slowdown". Business Insider. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Terms and Conditions". BetterHelp. October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (Oct 15, 2018). "Philip DeFranco, BetterHelp CEO speak out on YouTube's mental health controversy". Polygon. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ Philip DeFranco [@PhillyD] (October 15, 2018). "Before posting today's show I wanted to release a final update regarding BetterHelp. Thank you for taking the time to read" (Tweet). Retrieved October 16, 2018 – via Twitter.

- ^ Hale, James (February 11, 2019). "Philip DeFranco Launches Hair Care Line 'Beautiful Bastard,' Is On Track To Sell Out Today". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b DeFranco, Philip (April 23, 2019). Meet Deborah Sue Culwell. She's a Monster. Britney Spears, & Explaining 996 Censorship & Protests. The Philip DeFranco Show. YouTube. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

As some of you already saw because I snuck it into yesterday's description, our news website roguerocket.com has now officially launched.

- ^ a b Weiss, Geoff (July 1, 2019). "YouTube Vet Philip DeFranco Hits Play On 'Rogue Rocket' Channel With New Correspondents, Deeper Dives". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Dodgson, Lindsay (October 24, 2019). "Then and Now: How 30 of the world's most famous YouTubers have changed since their first videos". Insider. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Weiss, Geoff (March 27, 2020). "YouTube Taps Lilly Singh, Philip DeFranco, Others For Coronavirus Interview Series With Dr. Fauci". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (March 29, 2020). "Dr. Anthony Fauci closes distance with social media generation". NBC News. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (June 25, 2018). "YouTube is the new way to get famous. At VidCon, the tweens want to be next in line". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Behind the scenes at YouTube's "The Philip DeFranco Show"". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ Kessler, Sarah (August 4, 2014). "Inside YouTube's Fame Factory". Fast Company. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ Cornell, David (August 18, 2013). "YouTube Proposal: Philip DeFranco Pops The Question [Video]". The Inquisitr News. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Iansiti, Alex (February 28, 2015). "The Internet Ate My Newspaper". Huffington Post. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ a b McClain, James (December 3, 2019). "YouTube's Philip DeFranco Buys Encino Tennis Court Estate". Variety. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip (January 21, 2015). Giving Back vs. Keeping Mine. The Vloggity. YouTube. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ a b On Political Views, Trump, and Free Speech (Pt. 2) | Philip DeFranco | YOUTUBERS | Rubin Report, 7 September 2017, retrieved 2021-07-16

- ^ a b Epifani, Mike (March 19, 2017). "You can't be socially progressive and economically conservative". Quartz. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Wampfler, Josiah (October 1, 2012). "Philip DeFranco Comes out In Support of Gary Johnson". Daily Paul. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Julia (June 22, 2018). "Philip DeFranco says his YouTube show may change in the next 3 years". Polygon. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Chavez, Paij (August 13, 2019). "Chavez: Media Literacy is Crucial for America's Future". Daily Utah Chronicle. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Tenbarge, Kat (December 17, 2019). "PewDiePie and other YouTubers are angry at the mainstream media and it's just part of a deepening culture clash". Insider. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (September 7, 2016). "Here's What We Can Learn From The Reactions To YouTube's Demonetization Controversy". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Hamedy, Saba (September 1, 2016). "Everything you need to know about the Phil DeFranco #YouTubeIsOverParty drama". Mashable. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (April 5, 2019). "The golden age of YouTube is over". The Verge. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (March 4, 2020). "YouTube is demonetizing videos about coronavirus, and creators are mad". The Verge. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip (April 22, 2010). The Last PDS and How we killed 55.8 Black people in 1787. The Philip DeFranco Show. YouTube. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

This is the final Philip DeFranco Show. It's weird to say that and actually mean it.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (December 19, 2013). "2014 May Be The Final Year Of 'The Philip DeFranco Show'". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Gutelle, Sam (June 6, 2017). "Philip DeFranco Calls Out What He Sees As YouTube's Ad Double Standard, Vows To Take Next Show Elsewhere". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Weiss, Geoff (April 17, 2018). "Citing Viewership Suppression, Philip DeFranco Again Says New Shows Won't Be Distributed YouTube-First". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ DeFranco, Philip. "my 10 yr old sis sabrina now has an iphone". Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (August 19, 2013). "Philip DeFranco Proposed To His Girlfriend In Front Of 600 Fans". Tubefilter. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Philip DeFranco, YouTube Personality, Proposes To Girlfriend During 'DeFranco Does Arizona' Show (Video)". Huffington Post. August 20, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ @PhillyD (April 22, 2014). "Welcome to the world 8 lbs 11 oz #BabyDeFranco. We're going to call him TREY bc he is Philip DeFranco III. :)" (Tweet). Retrieved April 23, 2014 – via Twitter.

- ^ Votta, Rae (March 10, 2015). "YouTube royalty Phil DeFranco and Lindsay Doty tie the knot". The Daily Dot. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Klima, Jeff (March 25, 2015). "Philip DeFranco Wedding Video Is On YouTube". New Media Rockstars. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ @LinzDeFranco (September 8, 2017). "Carter William DeFranco. Born at 12:08am on 09/08/17 . 7lbs 11oz. 23inches" (Tweet). Retrieved September 8, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ^ Gutelle, Sam (April 5, 2018). "Philip DeFranco Answers Sean Evans' Burning Questions About YouTube On 'Hot Ones'". Tubefilter. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Wagyu 101 with Sean Evans and Philip DeFranco | Gochi Ganga". Complex. November 19, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "2nd Annual Nominees & Winners". Streamys. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "2013 IAWTV Awards Winners". International Academy of Web Television. January 9, 2013. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Break Out The Award Polish And Kleenex: The IAWTV Award Nominees Are In". New Media Rockstars. November 12, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "4th Annual Streamy Awards Nominees". Streamys. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "5th Annual Winners & Nominees". Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Lincoln, Ross A. (October 2, 2016). "2016 Streamy Awards: Full Winners List". Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Kelsey (September 26, 2017). "2016 Winners Announced for the 7th Annual Streamy Awards". Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ "7th Annual Nominees". Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "8th Annual Nominees & Winners". Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ a b "Winners Announced for the 9th Annual Streamy Awards". Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "10th Annual Nominees & Winners List". Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ "11th Annual Nominees & Winners List". Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ "12th Annual Nominees & Winners List". Retrieved December 5, 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1985 births

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century atheists

- American atheists

- American businesspeople in the online media industry

- American Internet company founders

- American libertarians

- American male bloggers

- American mass media company founders

- American people of Italian descent

- American political podcasters

- Businesspeople from Los Angeles

- Businesspeople from New York City

- East Carolina University alumni

- Former Roman Catholics

- Living people

- Maker Studios people

- News YouTubers

- YouTubers from Los Angeles

- YouTubers from the Bronx

- SourceFed people

- Streamy Award winners

- University of South Florida alumni

- Video game commentators

- YouTube channels launched in 2006

- American YouTube vloggers