Prison reform

| Criminology and penology |

|---|

|

Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of a penal system, reduce recidivism or implement alternatives to incarceration.[1] It also focuses on ensuring the reinstatement of those whose lives are impacted by crimes.[1]

In modern times, the idea of making living spaces safe and clean has extended from the civilian population to include prisons, based on ethical grounds. It is recognized that unsafe and unsanitary prisons violate constitutional prohibitions against cruel and unusual punishment. In recent times prison reform ideas include greater access to legal counsel and family, conjugal visits, proactive security against violence, and implementing house arrest with assistive technology.

History

[edit]

Prisons have only been used as the primary punishment for criminal acts in the last few centuries. Far more common earlier were various types of corporal punishment, public humiliation, penal bondage, and banishment for more severe offenses, as well as capital punishment, all of which occur today.[citation needed]

The concept of incarceration was presented circa 1750 as a more humane form of punishment than the corporal and capital punishment. They were originally designed as a way for criminals to participate in religious self-reflection and self-reform as a form of penance, hence the term penitentiary.[2]

Prisons contained both felons and debtors—the latter of which were allowed to bring in wives and children. The jailer made his money by charging the inmates for food and drink and legal services and the whole system was rife with corruption.[3] One reform of the sixteenth century was the establishment of the London Bridewell as a house of correction for women and children. This was the only place any medical services were provided.

Europe

[edit]Continental countries

[edit]The first public prison in Europe was Le Stinche in Florence, constructed in 1297, copied in several other cities. The more modern use grew from the prison workhouse (known as the Rasphuis) from 1600 in Holland. The house was normally managed by a married couple, the 'father' and 'mother', usually with a work master and discipline master. The inmates, or journeymen, often spent their time on spinning, weaving and fabricating cloths and their output was measured and those who exceeded the minimum received a small sum of money with which they could buy extras from the indoor father.[4]

An exception to the rule of forced labor were those inmates whose families could not look after them and paid for them to be in the workhouse. From the later 17th century private institutions for the insane, called the beterhuis, developed to meet this need.

In Hamburg, a different pattern occurred with the spinhaus in 1669, to which only infamous criminals were admitted. This was paid by the public treasury and the pattern spread in eighteenth-century Germany. In France the use of galley servitude was most common until galleys were abolished in 1748. After this the condemned were put to work in naval arsenals doing heavy work. Confinement originated from the hôpitaux généraux which were mostly asylums, though in Paris they included many convicts, and persisted up till the French Revolution.

The use of capital punishment and judicial torture declined during the eighteenth century and imprisonment came to dominate the system, although reform movements started almost immediately. Many countries were committed to the goal as a financially self-sustaining institution and the organization was often subcontracted to entrepreneurs, though this created its own tensions and abuse. By the mid nineteenth century several countries had initiated experiments in allowing the prisoners to choose the trades in which they were to be apprenticed. The growing amount of recidivism in the latter half of the nineteenth century led a number of criminologists to argue that "imprisonment did not, and could not fulfill its original ideal of treatment aimed at reintegrating the offender into the community".[5] Belgium led the way in introducing the suspended sentence for first-time offenders in 1888, followed by France in 1891 and most other countries in the next few years. Parole had been introduced on an experimental basis in France in the 1830s, with laws for juveniles introduced in 1850, and Portugal began to use it for adult criminals from 1861. The parole system introduced in France in 1885 made use of a strong private patronage network. Parole was approved throughout Europe at the International Prison Congress of 1910. As a result of these reforms the prison populations of many European countries halved in the first half of the twentieth century.

Exceptions to this trend included France and Italy between the world wars, when there was a huge increase in the use of imprisonment. The National Socialist state in Germany used it as an important tool to rid itself of its enemies as crime rates rocketed as a consequence of new categories of criminal behavior. Russia, which had only started to reform its penal and judicial system in 1860 by abolishing corporal punishment, continued the use of exile with hard labor as a punishment and this was increased to a new level of brutality under Joseph Stalin, despite early reforms by the Bolsheviks.

Postwar reforms stressed the need for the state to tailor punishment to the individual convicted criminal. In 1965, Sweden enacted a new criminal code emphasizing non-institutional alternatives to punishment including conditional sentences, probation for first-time offenders and the more extensive use of fines. The use of probation caused a dramatic decline in the number women serving long-term sentences: in France the number fell from 5,231 in 1946 to 1,121 in 1980. Probation spread to most European countries though the level of surveillance varies. In the Netherlands, religious and philanthropic groups are responsible for much of the probationary care. The Dutch government invests heavily in correctional personnel, having 3,100 for 4,500 prisoners in 1959.[6]

However, despite these reforms, numbers in prison started to grow again after the 1960s even in countries committed to non-custodial policies.

United Kingdom

[edit]18th century

[edit]During the eighteenth century, British justice used a variety of measures to punish criminals, including fines, the pillory and whipping. Transportation to the American colonies was used until 1776. The death penalty could be imposed for many offenses.[citation needed]

John Howard's book, The State of the Prisons was published in 1777.[7] He was particularly appalled to discover prisoners who had been acquitted but were still confined because they could not pay the jailer's fees. He proposed that each prisoner should be in a separate cell with separate sections for women felons, men felons, young offenders and debtors. The prison reform charity Howard League for Penal Reform takes its name from John Howard.

The Penitentiary Act 1779 (19 Geo. 3. c. 74) which passed following his agitation introduced solitary confinement, religious instruction and a labor regime and proposed two state penitentiaries, one for men and one for women. These were never built due to disagreements in the committee and pressures from wars with France and jails remained a local responsibility. But other measures passed in the next few years provided magistrates with the powers to implement many of these reforms and eventually in 1815 jail fees were abolished.

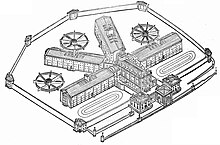

Quakers such as Elizabeth Fry continued to publicize the dire state of prisons as did Charles Dickens in his novels David Copperfield and Little Dorrit about the Marshalsea. Samuel Romilly managed to repeal the death penalty for theft in 1806, but repealing it for other similar offences brought in a political element that had previously been absent. The Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline, founded in 1816, supported both the Panopticon for the design of prisons and the use of the treadwheel as a means of hard labor. By 1824, 54 prisons had adopted this means of discipline.[8] Robert Peel's Gaols Act 1823 (4 Geo. 4. c. 64) attempted to impose uniformity in the country but local prisons remained under the control of magistrates until the Prison Act 1877 (40 & 41 Vict. c. 21).

19th century

[edit]The American separate system attracted the attention of some reformers and led to the creation of Millbank Prison in 1816 and Pentonville prison in 1842. By now the end of transportation to Australia and the use of hulks was in sight and Joshua Jebb set an ambitious program of prison building with one large prison opening per year. The main principles were separation and hard labour for serious crimes, using treadwheels and cranks. However, by the 1860s public opinion was calling for harsher measures in reaction to an increase in crime which was perceived to come from the 'flood of criminals' released under the penal servitude system. The reaction from the committee set up under the commissioner of prisons, Colonel Edmund Frederick du Cane, was to increase minimum sentences for many offences with deterrent principles of "hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed".[9] In 1877 he encouraged Disraeli's government to remove all prisons from local government and held a firm grip on the prison system till his forced retirement in 1895. He also established a tradition of secrecy which lasted till the 1970s so that even magistrates and investigators were unable to see the insides of prisons.[10] By the 1890s the prison population was over 20,000.

1877–1914

[edit]The British penal system underwent a transition from harsh punishment to reform, education, and training for post-prison life. The reforms were controversial and contested. In 1877–1914 era a series of major legislative reforms enabled significant improvement in the penal system. In 1877, the previously localized prisons were nationalized in the Home Office under a Prison Commission. The Prison Act 1898 (61 & 62 Vict. c. 41) enabled the Home Secretary to and multiple reforms on his own initiative, without going through the politicized process of Parliament. The Probation of Offenders Act 1907 (7 Edw. 7. c. 17) introduced a new probation system that drastically cut down the prison population while providing a mechanism for transition back to normal life. The Criminal Justice Administration Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 58) required courts to allow a reasonable time before imprisonment was ordered for people who did not pay their fines. Previously tens of thousands of prisoners had been sentenced solely for that reason. The Borstal system after 1908 was organized to reclaim young offenders, and the Children Act 1908 (8 Edw. 7. c. 67) prohibited imprisonment under age 14, and strictly limited that of ages 14 to 16. The principal reformer was Sir Evelyn Ruggles-Brise. the chair of the Prison Commission.[11][12]

Winston Churchill

[edit]Major reforms were championed by The Liberal Party government in 1906–1914. The key player was Winston Churchill when he was the Liberal Home Secretary, 1910–11.[13] He first achieved fame as a prisoner in the Boer war in 1899. He escaped after 28 days and the media, and his own book, made him a national hero overnight.[14] He later wrote, "I certainly hated my captivity more than I have ever hated any other in my whole life... Looking back on those days I've always felt the keenest pity for prisoners and captives."[15] As Home Secretary he was in charge of the nation's penal system. Biographer Paul Addison says. "More than any other Home Secretary of the 20th century, Churchill was the prisoner's friend. He arrived at the Home Office with the firm conviction that the penal system was excessively harsh." He worked to reduce the number sent to prison in the first place, shorten their terms, and make life in prison more tolerable, and rehabilitation more likely.[16] His reforms were not politically popular, but they had a major long-term impact on the British penal system.[17][18]

Borstal system

[edit]During 1894–95, Herbert Gladstone's Committee on Prisons showed that criminal propensity peaked from the mid-teens to the mid-twenties. He took the view that central government should break the cycle of offending and imprisonment by establishing a new type of reformatory, that was called Borstal after the village in Kent which housed the first one. The movement reached its peak after the first world war when Alexander Paterson became commissioner, delegating authority and encouraging personal responsibility in the fashion of the English Public school: cellblocks were designated as 'houses' by name and had a housemaster. Cross-country walks were encouraged, and no one ran away. Prison populations remained at a low level until after the second world war when Paterson died and the movement was unable to update itself.[19] Some aspects of Borstal found their way into the main prison system, including open prisons and housemasters, renamed assistant governors and many Borstal-trained prison officers used their experience in the wider service. But in general the prison system in the twentieth century remained in Victorian buildings which steadily became more and more overcrowded with inevitable results.

United States

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (September 2022) |

In colonial America, punishments were severe. The Massachusetts assembly in 1736 ordered that a thief, on first conviction, be fined or whipped. The second time he was to pay treble damages, sit for an hour upon the gallows platform with a noose around his neck and then be carted to the whipping post for thirty stripes. For the third offense he was to be hanged.[20] But the implementation was haphazard as there was no effective police system and judges would not convict if they believed the punishment was excessive. The local jails mainly held men awaiting trial or punishment and those in debt.

In the aftermath of independence most states amended their criminal punishment statutes. Pennsylvania eliminated the death penalty for robbery and burglary in 1786, and in 1794 retained it only for first degree murder. Other states followed and in all cases the answer to what alternative penalties should be imposed was incarceration. Pennsylvania turned its old jail at Walnut Street into a state prison. New York built Newgate state prison in Greenwich Village and other states followed. But by 1820 faith in the efficacy of legal reform had declined as statutory changes had no discernible effect on the level of crime and the prisons, where prisoners shared large rooms and booty including alcohol, had become riotous and prone to escapes.

In response, New York developed the Auburn system in which prisoners were confined in separate cells and prohibited from talking when eating and working together, implementing it at Auburn State Prison and Sing Sing at Ossining. The aim of this was rehabilitative: the reformers talked about the penitentiary serving as a model for the family and the school and almost all the states adopted the plan (though Pennsylvania went even further in separating prisoners). This changed after Elam Lynds became agent and keeper of the prison and advanced a philosophy that no amount of punishment can reduce criminality. Lynds dismissed the concept of reform, instead treating prison labor as a resource to be exploited to the maximum capacity of the prisoner's human body. Lynds' approach became know, visitors to the U.S. to see the prisons that followed his approach included de Tocqueville, who wrote Democracy in America as a result of his visit. The system was criticized by prison reformers across the country, who preferred the Pennsylvania System and its focus on saving prisoners' souls.[21]

By the 1860s prison overcrowding became an issue, in part because of the long sentences given for violent crimes and despite harsh treatment of prisoners. An increasing proportion of prisoners were new immigrants. As a result of a tour of prisons in 18 states, Enoch Wines and Theodore Dwight produced a monumental report describing the flaws in the existing system and proposing remedies.[22] Their critical finding was that not one of the state prisons in the United States was seeking the reformation of its inmates as a primary goal.[23] They set out an agenda for reform which was endorsed by a National Congress in Cincinnati in 1870. These ideas were put into practice in the Elmira Reformatory in New York in 1876 run by Zebulon Brockway. At the core of the design was an educational program which included general subjects and vocational training for the less capable. Instead of fixed sentences, prisoners who did well could be released early.

But by the 1890s, Elmira had twice as many inmates as it was designed for and they were not only the first offenders between 16 and 31 for which the program was intended. Although it had a number of imitators in different states, it did little to halt the deterioration of the country's prisons which carried on a dreary life of their own. In the southern states, in which blacks made up more than 75% of the inmates, there was ruthless exploitation in which the states leased prisoners as chain gangs to entrepreneurs who treated them worse than slaves. By the 1920s drug use in prisons was also becoming a problem.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, psychiatric interpretations of social deviance were gaining a central role in criminology and policy making. By 1926, 67 prisons employed psychiatrists and 45 had psychologists. The language of medicine was applied in an attempt to "cure" offenders of their criminality. In fact, little was known about the causes of their behaviour and prescriptions were not much different from the earlier reform methods.[24] A system of probation was introduced, but often used simply as an alternative to suspended sentences, and the probation officers appointed had little training, and their caseloads numbered several hundred making assistance or surveillance practically impossible. At the same time they could revoke the probation status without going through another trial or other proper process.[25]

In 1913, Thomas Mott Osborne became chairman of a commission for the reform of the New York prison system and introduced a Mutual Welfare League at Auburn with a committee of 49 prisoners appointed by secret ballot from the 1400 inmates. He also removed the striped dress uniform at Sing Sing and introduced recreation and movies. Osborne published in 1916 the book Society and Prisons: Some Suggestions for a New Penology, which influenced the discussion of prison reform and contributed to a change in societal perceptions of incarcerated individuals.[26][27] Progressive reform resulted in the "Big House" by the late twenties – prisons averaging 2,500 men with professional management designed to eliminate the abusive forms of corporal punishment and prison labor prevailing at the time.

The American prison system was shaken by a series of riots in the early 1950s triggered by deficiencies of prison facilities, lack of hygiene or medical care, poor food quality, and guard brutality. In the next decade all these demands were recognized as rights by the courts.[24] In 1954, the American Prison Association changed its name to the American Correctional Association and the rehabilitative emphasis was formalized in the 1955 United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

Since the 1960s the prison population in the US has risen steadily, even during periods where the crime rate has fallen. This is partly due to profound changes in sentencing practices due to a denunciation of lenient policies in the late sixties and early seventies and assertions that rehabilitative purposes do not work. As a consequence sentencing commissions started to establish minimum as well as maximum sentencing guidelines, which have reduced the discretion of parole authorities and also reduced parole supervision of released prisoners. Another factor that contributed to the increase of incarcerations was the Reagan administration's "War On Drugs" in the 1980s. This War increased money spent on lowering the number of illegal drugs in the United States. As a result, drug arrests increased and prisons became increasingly more crowded.[28] The rising prison population was made up disproportionately of African American with 90% of those sentenced to prison for drug offense in Illinois in 2002.[29] By 2010, the United States had more prisoners than any other country and a greater percentage of its population was in prison than in any other country in the world. "Mass incarceration" became a serious social and economic problem, as each of the 2.3 million American prisoners costs an average of about $25,000 per year. Recidivism remained high, and useful programs were often cut during the recession of 2009–2010. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Plata upheld the release of thousands of California prisoners due to California's inability to provide constitutionally mandated levels of healthcare.

In 2015, a bipartisan effort was launched by Koch family foundations, the ACLU, the Center for American Progress, Families Against Mandatory Minimums, the Coalition for Public Safety, and the MacArthur Foundation to more seriously address criminal justice reform in the United States.[30][31] The Kochs and their partners are combatting the systemic overcriminalization and overincarceration of citizens from primarily low-income and minority communities.[32][33] The group of reformers is working to reduce recidivism rates and diminish barriers faced by rehabilitated persons seeking new employment in the work force. In addition they have a goal in ending Asset forfeiture practices since law enforcement often deprives individuals of the majority of their private property.[34]

Decarceration in the United States includes overlapping reformist and abolitionist strategies, from "front door" options such as sentencing reform, decriminalization, diversion and mental health treatment to "back door" approaches, exemplified by parole reform and early release into community supervision programs, amnesty for inmates convicted of non-violent offenses and imposition of prison capacity limits.[35] While reforms focus on incremental changes, abolitionist approaches include budget reallocations, prison closures and restorative and transformative justice programs that challenge incarceration as an effective deterrent and necessary means of incapacitation. Abolitionists support investments in familial and community mental health, affordable housing and quality education to gradually transition and jail employees to jobs in other economic sectors.[36][37][38]

Theorists

[edit]

Numerous theorists have written on the topic of prison reform and advocated for scientific, compassionate, and evidence-based approaches to rehabilitation. One of the most famous was Thomas Mott Osborne, former prison commander of Portsmouth Naval Prison and former warden of New York's Sing Sing prison, who himself chose to live briefly as a prisoner to better understand the prison experience.[39] Osborne was a mentor to other renowned prison reform theorists, such as Austin MacCormick. Prisoners themselves, such as Victor Folke Nelson,[40] have also contributed to the theories and literature on American prison reform.

Theories of incarceration and reform

[edit]Retribution, vengeance and retaliation

[edit]This is founded on the "eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth" incarceration philosophy, which essentially states that if one person harms another, then equivalent harm should be done to them. One goal here is to prevent vigilantism, gang or clan warfare, and other actions by those who have an unsatisfied need to "get even" for a crime against them, their family, or their group. It is, however, difficult to determine how to equate different types of "harm". A literal case is where a murderer is punished with the death penalty, the argument being "justice demands a life for a life". One criticism of long term prison sentences and other methods for achieving justice is that such "warehousing" of criminals is rather expensive, this argument notwithstanding the fact that the multiple incarceration appeals of a death penalty case often exceed the price of the "warehousing" of the criminal in question. Yet another facet of this debate disregards the financial cost for the most part. The argument regarding warehousing rests, in this case, upon the theory that any punishment considered respectful of human rights should not include imprisoning humans for life without a chance of release—that even death is morally and ethically a higher road than no-parole prison sentences.

Deterrence

[edit]The criminal is used as a "threat to themselves and others". By subjecting prisoners to harsh conditions, authorities hope to convince them to avoid future criminal behavior and to exemplify for others the rewards for avoiding such behavior; that is, the fear of punishment will win over whatever benefit or pleasure the illegal activity might bring. The deterrence model frequently goes far beyond "an eye for an eye", exacting a more severe punishment than would seem to be indicated by the crime. Torture has been used in the past as a deterrent, as has the public embarrassment and discomfort of stocks, and, in religious communities, ex-communication. Executions, particularly gruesome ones (such as hanging or beheading), often for petty offenses, are further examples of attempts at deterrence. One criticism of the deterrence model is that criminals typically have a rather short-term orientation, and the possibility of long-term consequences is of little importance to them. Also, their quality of life may be so horrific that any treatment within the criminal justice system (which is compatible with human rights law) will only be seen as an improvement over their previous situation. There used to be many European Monks who disagreed with the containment of the mentally ill, and their ethics had a strong influence on Dorothea Dix's mission to find a proper way to care for the challenged people.

Rehabilitation, reform and correction

[edit]("Reform" here refers to reform of the individual, not the reform of the penal system.) The goal is to "repair" the deficiencies in the individual and return them as productive members of society. Education, work skills, deferred gratification, treating others with respect, and self-discipline are stressed. Younger criminals who have committed fewer and less severe crimes are most likely to be successfully reformed. Art therapy is also considered to be beneficial for working with challenging prison demographics.[41] "Reform schools" and "boot camps" are set up according to this model. One criticism of this model is that criminals are rewarded with training and other items which would not have been available to them had they not committed a crime.

Art Therapy is a method of rehabilitation employed across the United States, especially in California. San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, formally known as San Quentin State Prison, is the oldest prison in California. Although primarily known for death row, it has recently been reformed into a hub for many rehabilitation programs under Governor Gavin Newsom.[42] The recognition of the benefits of art therapy began as at least as early as 1840.[43] California has implemented an Arts in Corrections program focused on providing incarcerated individuals across 35 adult facilities with the tools to express themselves visually, musically, and in writing. States like Colorado and Florida have provided similar resources to other facilities through adjacent initiatives like the FSU Art Therapy in Prisons Program.[41][43] There have been significant associations made between rehabilitative programs and reduced recidivism rates, but some groups think it's important to emphasize right to participate in these art programs without the focus only being on reintegration to society.[44]

Prior to its closing in late 1969, Eastern State Penitentiary, formally known as State Correctional Institution, Philadelphia, had established a far reaching program of voluntary group therapy with the goal of having all inmates in the prison involved. From 1967 when the plan was initiated, the program appears to have been successful as many inmates did volunteer for group therapy. An interesting aspect was that the groups were to be led by two therapists, one from the psychology or social work department and a second from one of the officers among the prison guard staff.[45]

Removal from society

[edit]The goal here is simply to keep criminals away from potential victims, thus reducing the number of crimes they can commit. The criticism[citation needed] of this model is that others increase the number and severity of crimes they commit to make up for the "vacuum" left by the removed criminal. For example, incarcerating a drug dealer will result in an unmet demand for drugs at that locale, and an existing or new drug dealer will then appear, to fill the void. This new drug dealer may have been innocent of any crimes before this opportunity, or may have been guilty of less serious crimes, such as being a look-out for the previous drug dealer.

Restitution or repayment

[edit]Prisoners are forced to repay their "debt" to society. Unpaid or low pay work is common in many prisons, often to the benefit of the community. In some countries prisons operate as labour camps. Critics say that the repayment model gives government an economic incentive to send more people to prison. In corrupt or authoritarian regimes, such as the former Soviet Union under the control of Joseph Stalin, many citizens are sentenced to forced labour for minor breaches of the law, simply because the government requires the labour camps as a source of income. Community service is increasingly being used as an alternative to prison for petty criminals.[46]

Reduction in immediate costs

[edit]Government and prison officials also have the goal of minimizing short-term costs; however, there could be a way for prisons to become self-sustaining independent institutions—with little need for government funds.

- In wealthy societies:

- This calls for keeping prisoners placated by providing them with things like television and conjugal visits. Inexpensive measures like these prevent prison assaults and riots which in turn allow the number of guards to be minimized. Providing the quickest possible parole and/or release also reduces immediate costs to the prison system (although these may very well increase long term costs to the prison system and society due to recidivism). The ultimate way to reduce immediate costs is to eliminate prisons entirely and use fines, community service, and other sanctions (like the loss of a driver's license or the right to vote) instead. Executions at first would appear to limit costs, but, in most wealthy societies, the long appeals process for death sentences (and associated legal costs) make them quite expensive. Note that this goal may conflict with a number of goals for criminal justice systems.

- In poor societies:

- Poor societies, which lack the resources to imprison criminals for years, frequently use execution in place of imprisonment, for severe crimes. Less severe crimes, such as theft, might be dealt with by less severe physical means, such as amputation of the hands. When long term imprisonment is used in such societies, it may be a virtual death sentence, as the lack of food, sanitation, and medical care causes widespread disease and death, in such prisons.

Some of the goals of criminal justice are compatible with one another, while others are in conflict. In the history of prison reform, the harsh treatment, torture, and executions used for deterrence first came under fire as a violation of human rights. The salvation goal, and methods, were later attacked as violations of the individual's freedom of religion. This led to further reforms aimed principally at reform/correction of the individual, removal from society, and reduction of immediate costs. The perception that such reforms sometimes denied victims justice then led to further changes.

Advocacy work

[edit]John Howard is now widely regarded as the founding father of prison reform, having travelled extensively visiting prisons across Europe in the 1770s and 1780s. Also, the great social reformer Jonas Hanway promoted "solitude in imprisonment, with proper no one asked profitable labor and a spare diet".[47] Indeed, this became the popular model in England for many decades.

United Kingdom

[edit]Within Britain, prison reform was spearheaded by the Quakers, and in particular, Elizabeth Fry during the Victorian Age. Elizabeth Fry visited prisons and suggested basic human rights for prisoners, such as privacy and teaching prisoners a trade. Fry was particularly concerned with women's rights. Parliament, coming to realize that a significant portion of prisoners had come to commit crimes as a result of mental illness, passed the County Asylums Act (1808). This made it possible for Justice of the Peace in each county to build and run their own pauper asylums.

"Whereas the practice of confining such lunatics and other insane persons as are chargeable to their respective parishes in Gaols, Houses of Correction, Poor Houses and Houses of Industry, is highly dangerous and inconvenient"[48]

There is contemporary research on the use of volunteers by governments to help ensure the fair and humane detention of prisoners.[49] Research suggests that volunteers can be effective to ensure oversight of state functions and ensure accountability, however, they must be given tasks appropriately and well trained.[49]

United States

[edit]

In the 1800s, Dorothea Dix toured prisons in the U.S. and all over Europe looking at the conditions of the mentally handicapped. Her ideas led to a mushroom effect of asylums all over the United States in the mid-19th-century. Linda Gilbert established 22 prison libraries of from 1,500 to 2,000 volumes each, in six states.[citation needed]

In the early 1900s Samuel June Barrows was a leader in prison reform. President Cleveland appointed him International Prison Commissioner for the U.S. in 1895, and in 1900, Barrows became Secretary of the Prison Association of New York and held that position until his death on April 21, 1909. A Unitarian pastor, Barrows used his influence as editor of the Unitarian Christian Register to speak at meetings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction, the National International Prison Congresses, and the Society for International Law. As the International Prison Commissioner for the U.S., he wrote several of today's most valuable documents of American penological literature, including "Children's Courts in the United States" and "The Criminal Insane in the United States and in Foreign Countries". As a House representative, Barrows was pivotal in the creation of the International Prison Congress and became its president in 1905. In his final role, as Secretary of the Prison Association of New York, he dissolved the association's debt, began issuing annual reports, drafted and ensured passage of New York's first probation law, assisted in the implementation of a federal Parole Law, and promoted civil service for prison employees. Moreover, Barrows advocated improved prison structures and methods, traveling in 1907 around the world to bring back detailed plans of 36 of the best prisons in 14 different countries. In 1910 the National League of Volunteer Workers, nicknamed the "Barrows League" in his memory, formed in New York as a group dedicated to helping released prisoners and petitioning for better prison conditions.

Zebulon Brockway in Fifty Years of Prison Service outlined an ideal prison system: Prisoners should support themselves in prison though industry, in anticipation of supporting themselves outside prison; outside businesses and labor must not interfere; indeterminate sentences were required, making prisoners earn their release with constructive behavior, not just the passage of time; and education and a Christian culture should be imparted. Nevertheless, opposition to prison industries, the prison-industrial complex, and labor increased. Finally, U.S. law prohibited the transport of prison-made goods across state lines. Most prison-made goods today are only for government use—but the state and federal governments are not required to meet their needs from prison industries. Although nearly every prison reformer in history believed prisoners should work usefully, and several prisons in the 1800s were profitable and self-supporting, most American prisoners today do not have productive jobs in prison.[50]

Kim Kardashian-West has fought for prison reform, notably visiting the White House to visit President Donald Trump in on May 30, 2018. In 2018, Trump announced he was providing clemency to Alice Johnson, a week after the meeting with Kardashian-West. Johnson was given a life sentence for drug charges.[51] She has also helped with lobbying the First Step Act, reducing the federally mandated minimum prison sentences.

Rappers Jay-Z and Meek Mill have also been advocates for prison reform, both being very outspoken about the issue. In 2019, they announced the launching of an organization, REFORM Alliance, which aims to reduce the number of people who are serving probation and parole sentences that are unjust. The organization was able to pledge $50 million to debut, also deciding to bring on CNN news commentator Van Jones as CEO.[52]

Musician Johnny Cash performed and recorded at many prisons and fought for prison reform.[53][54][55][56] His song "Folsom Prison Blues" tells the tale from the perspective of a convicted killer in prison. It is named after Folsom State Prison, which is California's second oldest correctional facility. Twelve years after the song was released, Cash performed it live at the prison.

Not all prison reformers approach the problem from the left side of the political spectrum, although most do. In "How to Create American Manufacturing Jobs", it was proposed that restrictions on prison industries and labor and federal employment laws be eliminated so that prisoners and private employers could negotiate wage agreements to make goods now made exclusively overseas.[57] This would boost prison wages and revitalize prison industries away from the money-losing state industries approach that now limits prison labor and industries. Prisoners want to work, but there are not enough jobs in prison for them to be productive. Nonprofit can help voice issues as seen by inmates on the other side, however limits to funding and access to those currently incarcerated limit the ability of these NGOs.[58]

On December 21, 2018, President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act bill into law. The First Step Act has provisions to ease prison sentences for drug related crimes, and promote good behavior in federal prisons.[59] Clementine Jacoby's Recidiviz looks to reduce incarceration rates by making complex and fragmented criminal justice data usable, which enables leaders to take data-driven action and track the impacts of their decisions.[60]

See also

[edit]- Death in custody

- Decarceration in the United States

- Incarceration in Norway

- LGBT people in prison

- Mentally ill people in United States jails and prisons

- Penal Reform International

- Preservation of the Rights of Prisoners (PROP)

- Prison abolition movement

- Prison conditions in France

- Prison education

- Prison strike

- Prisoner abuse

- Prisoner suicide

- Prisoners' Union[disambiguation needed]

- Restorative justice

- Sentencing disparity

References

[edit]- ^ a b Harris, Duchess; Conley, Kate (2020). The US Prison System and Prison Life. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Essential Library. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781532119224.

- ^ Davis, Angela Y. "Imprisonment and Reform" Dimensions of Culture 2: Justice, edited by Dr. Amanda Solomon, Dr. Megan Strom, and Dr. Emily Johnson, Cognella, 2019, pp. 95-102.

- ^ Sarraf, Sanjay (April 2023). "Beyond The Walls: A Comprehensive Look At The History And Future Of Open Prisons" (PDF). Retrieved 10 October 2024 – via International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT) Volume 11, Issue 4, page 6 ISSN: 2320-2882.

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, pp. 68–72

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, pp. 210

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, pp. 218–222

- ^ John Howard (1777), The State of the Prisons in England and Wales with an account of some foreign prisons

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, p. 97

- ^ Fox 1952, p. 46

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, p. 153

- ^ R. C. K. Ensor. ‘’ England 1870-1914’’ (1937) pp 520-21.

- ^ J.W. Fox, ‘’The Modern English Prison ‘’ (1934).

- ^ Jamie Bennett, "The Man, the Machine and the Myths: Reconsidering Winston Churchill’s Prison Reforms." in Helen Johnston, ed., Punishment and Control in Historical Perspective (2008) pp. 95-114. online Archived 2018-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Candice Millard (2016). Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill. London: Random House Large Print. p. 563. ISBN 9780804194891.

- ^ Paul Addison (2005). Churchill: The Unexpected Hero. OUP Oxford. p. 51. ISBN 9780191608575. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Addison, p. 51.

- ^ Edward Moritz, Jr., "Winston Churchill - Prison Reformer," The Historian 20#4 (1958), pp. 428-440 JSTOR 24437567

- ^ Victor Bailey, "Churchill As Home-Secretary--Prison Reform." History Today vol 35 (March 1985): 10-13.

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, pp. 157–161

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, p. 113

- ^ Bernstein, Robin (2024). Freeman's Challenge: The Murder That Shook America's Original Prison for Profit. The University of Chicago Press. p. 17—19.

- ^ Enoch Wines; Theodore Dwight (1867), Report on the Prisons and Reformatories of the United States and Canada

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, p. 172

- ^ a b Morris & Rothman 1995, p. 178

- ^ Morris & Rothman 1995, p. 182

- ^ Tannenbaum, Frank (1933). Osborne of Sing Sing. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 103.

- ^ McKelvey, Blake (1977). American prisons: A history of good intentions. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith. pp. 262–265.

- ^ Miles, Kathleen (10 March 2014). "Just How Much The War On Drugs Impacts Our Overcrowded Prisons, In One Chart". Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2019 – via Huff Post.

- ^ Alexander, Michelle. "The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color Blindness." Dimensions of Culture 2: Justice, Edited by Dr. Amanda Solomon, Dr. Megan Strom, and Dr. Emily Johnston, Cognella, 2019, pp. 89-94.

- ^ Ball, Molly (Mar 3, 2015). "Do the Koch Brothers Really Care About Criminal-Justice Reform?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Mak, Tim (Jan 13, 2015). "Koch Bros to Bankroll Prison Reform". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Horwitz, Sari (Aug 15, 2015). "Unlikely Allies". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Gass Henry (Oct 20, 2015). "Congress's big, bipartisan success that might be just beginning". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Hudetz, Mary (Oct 15, 2015). "Forfeiture reform aligns likes of billionaire Charles Koch, ACLU". The Topeka Capital Journal. Archived from the original on 2016-01-14. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ^ "NCJRS Abstract - National Criminal Justice Reference Service". www.ncjrs.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "Decarceration Strategies: How 5 States Achieved Substantial Prison Population Reductions". The Sentencing Project. 5 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2022-05-20. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ Arrieta-Kenna, Ruairí (15 August 2018). "'Abolish Prisons' Is the New 'Abolish ICE'". POLITICO Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ Hyperakt (2020-05-02). "Vera Institute". Vera. Archived from the original on 2020-05-02. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ "Thomas Mott Osborne and Prison Reform – Cayuga Museum of History and Art. Archived 2022-02-09 at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved on February 8, 2022.

- ^ Prison Days and Nights, by Victor F. Nelson (New York: Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., 1936)

- ^ a b Soape, Evie; Barlow, Casey; Gussak, David E.; Brown, Jerry; Schubarth, Anna (September 2022). "Creative IDEA: Introducing a Statewide Art Therapy in Prisons Program". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 66 (12): 1285–1302. doi:10.1177/0306624X211013731. ISSN 0306-624X. PMID 33971757.

- ^ "Winter/Spring 2024". The Journal of Values-Based Leadership. 17 (1). 2023-12-20. doi:10.22543/1948-0733.1510. ISSN 1948-0733.

- ^ a b Littman, Danielle Maude; Sliva, Shannon M. (2020). "Prison Arts Program Outcomes: A Scoping Review". Journal of Correctional Education (1974-). 71 (3): 54–82. ISSN 0740-2708. JSTOR 27042216.

- ^ Horneman-Wren, Brigid (2021-09-01). "Prison art programs: Art, culture and human rights for Indigenous prisoners". Alternative Law Journal. 46 (3): 219–224. doi:10.1177/1037969X211008977. ISSN 1037-969X.

- ^ Bernard, Mazie (2005). Prison Manifesto: Recollections of a Queer Psychologist Working in a Maximum Security Prison. Bernard Mazie. ISBN 978-0-9769715-0-4.

- ^ "New York Times". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ Hanway, Jonas (1776) Solitude in Imprisonment: With Proper Profitable Labour and a Spare Diet, the Most Humane and... J. Bew. Retrieved 2006-10-30

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (1981). "Table of Statutes". The asylums index. Middlesex University, London, England. Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ^ a b Roffee, James A. (2017-01-01). "Accountability and Oversight of State Functions: Use of Volunteers to Monitor Equality and Diversity in Prisons in England and Wales". SAGE Open. 7 (1): 2158244017690792. doi:10.1177/2158244017690792. hdl:1959.3/444560. ISSN 2158-2440.

- ^ One in 100: Behind Bars in America Archived 2017-10-31 at the Wayback Machine, 2008, Pew Center's Public Safety Performance Project @ pewcenteronthestates; Stephen Garvey, "Freeing Prisoners' Labor," 50 Stanford Law Review 339, 343 (1–1998); John Dewar Gleissner, Prison & Slavery – A Surprising Comparison, Outskirts Press, 2010.

- ^ Jeremy Diamond and Kaitlan Collins (6 June 2018). "Trump commutes sentence of Alice Marie Johnson". CNN. Archived from the original on 2018-06-06. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ^ Lisa Respers France (24 January 2019). "Jay-Z and Meek Mill launch prison reform organization". CNN. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ Lundy, Zeth. "PopMatters". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ Antonino D'Ambrosio (November 9, 2009). "The bitter tears of Johnny Cash". Salon.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ Streissguth, Michael (2006-09-04). Books.google.com. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306813689. Archived from the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ Respers, Lisa (January 24, 2019). "Jay-Z and Meek Mill launch prison reform organization". CNN. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ John Dewar Gleissner, How to Create American Manufacturing Jobs, Vol. 9, Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy, Issue 3 (2013) @ https://trace.tennessee.edu/tjlp/vol9/iss3/4 Archived 2020-06-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A Voice from Prison Blog | Criminal Justice Reform & Constitutional Rights". A Voice from Prison. Archived from the original on 2022-08-13. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- ^ Lopez, German (2018-12-18). "The First Step Act, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on 2022-09-01. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ "Recidiviz | A Criminal Justice Data Platform". www.recidiviz.org. Archived from the original on 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

Further reading

[edit]- International Journal of Prisoner Health, Taylor & Francis Publishing

- Cheney, Glenn A. Lurking Doubt: Notes on Incarceration, New London Librarium, 2018. ISBN 978-1-947074-15-6

- Denborough, D. (Ed.) (1996). Beyond the prison: Gathering dreams of freedom. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications.

- Dilulio, John J., Governing Prisons: A Comparative Study of Correctional Management, Simon and Schuster, 1990. ISBN 0-02-907883-0

- Fox, Lionel W. (1952), The English Prison and Borstal Systems, Routledge and Kegan Paul, ISBN 9780415177382

- Johnston, Helen, ed., Punishment and Control in Historical Perspective (2008) online

- Morris, Norval; Rothman, David J. (1995), Oxford History of the Prison, New York, Oxford University Press

- Serrill, M. S., "Norfolk – A Retrospective – New Debate Over a Famous Prison Experiment," Corrections Magazine, Volume 8, Issue 4 (August 1982), pp. 25–32.

- United States. Congress. House of Representatives. (2014). Lessons From the States: Responsible Prison Reform: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, Homeland Security, and Investigations of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, Second Session, July 15, 2014. Washington, D.C.: G.P.O.

- SpearIt, Evolving Standards of Domination: Abandoning a Flawed Legal Standard and Approaching a New Era in Penal Reform (March 2, 2015). Chicago-Kent Law Review, Vol. 90, 2015. Online

- Wray, Harmon (1989). "Cells for Sale". Southern Changes. 8 (3): 3–6. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01.

- Wray, Harmon; Hutchison, Peggy (2002). Restorative Justice: Moving Beyond Punishment. New York: General Board of Global Ministries, the United Methodist Church. ISBN 9781890569341. OCLC 50796239.

- Magnani, Laura; Wray, Harmon L. (2006). Beyond Prisons: A New Interfaith Paradigm for our Failed Prison System. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress. ISBN 9780800638320. OCLC 805054899.

- Kaba, Mariame; Murakawa, Naomi (2021). We do this 'til we free us : abolitionist organizing and transforming justice. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books. ISBN 9781642595253. OCLC 1240267964.

External links

[edit]- Howard League for Penal Reform

- Penal Reform International (PRI)

- Preventing Prisoner Rape Project A national project in Australia, aiming to raise awareness about the issue of rape in prisons, and support survivors, their families, and workers in prisons dealing with sexual assault. Website contains free downloadable resources.

- UNODC – United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – Justice and Prison Reform

- Prison and Judicial Reform Research