Mexican Liberal Party

Mexican Liberal Party Partido Liberal Mexicano | |

|---|---|

| |

| President | Ricardo Flores Magón |

| Vice President | Juan Sarabia (1905–1911) |

| Founded | 28 September 1905[1][2] |

| Dissolved | 1918 |

| Split from | Liberal Party |

| Headquarters | Mexico City |

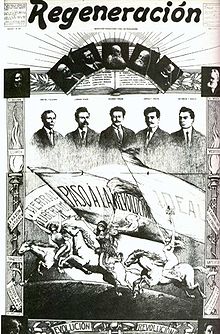

| Newspaper | Regeneración |

| Ideology | Magonism[3] Radicalism[4][5] Jacobinism[6] Anarcho-syndicalism[7] |

| Political position | Far-left |

| Colours | Red Black |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Radicalism |

|---|

|

The Mexican Liberal Party (Spanish: Partido Liberal Mexicano, PLM) was founded in August 1900 when engineer Camilo Arriaga published a manifesto entitled Invitacion al Partido Liberal (Invitation to the Liberal Party). The invitation was addressed to Mexican liberals who were dissatisfied with the way the government of Porfirio Díaz was deviating from the liberal Constitution of 1857.[8] Arriaga called on Mexican liberals to form local liberal clubs, which would then send delegates to a liberal convention.[9]

The first Mexican Liberal Party Convention was held in San Luis Potosí in February 1901. Fifty local clubs from thirteen states sent 56 delegates.[10] The Convention delegates affirmed their liberal beliefs in free speech, free press, and free assembly. They objected to the close workings of the Diaz government and the Catholic Church.[11] The convention produced fifty-one resolutions which called for the organization of the new Liberal Party, propagation of liberal principles, development of means to combat the political influence of the clergy, establishment of means to improve the administration of justice, proposals calling for guarantees of the rights of citizens and real freedom of the press, and proposals favoring complete self-government at the local level. They also called for support for free secular education in the primary schools, the spread of liberal ideas among the lower classes, the establishment of liberal publications, and the taxation of Church income.[12]

Ricardo Flores Magón attended the first Convention as a reporter for his newspaper Regeneración ("Regeneration"). He afterwards published an editorial in favorable support of the aims and aspirations. In April 1901, the new Mexican Liberal Party opened a branch in Mexico City, and Ricardo Flores Magón and his brothers joined and became active members. Always a bit more radical than most members, Flores Magón was forced into exile in January 1904. Finally settling in San Antonio, Texas, Flores Magón called for radical members of the Liberal Party to follow him in a new organization. In September 1905, the radical liberals, led by Flores Magón, formed a new organization called Junta Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM). This organization would be separate from the Liberal Party, and it would seek to coordinate the violent overthrow of the Díaz government.[13] The PLM was involved in strikes and uprisings in Mexico from 1906 to 1911.

Overview

[edit]The party controlled the northern part of Baja California in 1911, including Tijuana, Mexicali, and Tecate. In August 1911 part of the PLM militants, including Juan Sarabia, Jesús Flores Magón and Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama split from the organization and transformed into the "Liberal Party" (Spanish: Partido Liberal).[14]

The PLM was supported from exile in Texas by the feminist writer Andrea Villarreal.

Background

[edit]In February 1901, the Liberal Congress was founded in San Luis Potosí, in which representatives of fourteen states of the Mexican Republic demanded to dismiss the postulates of the Constitution of 1857. Dozens of liberal clubs were created throughout the country and an attempt was made to establish a "Confederation of Liberal Circles", but the following year its founders were arrested. Porfirio Díaz severely repressed the entire opposition and in 1902 he was re-elected as president of Mexico for the third time.

By 1904 the police persecution of the Diaz government, its political opponents were forced to seek refuge abroad, coupled with the growing political differences between the liberals, a group headed by Camilo Arriaga, went into exile in San Antonio, Texas, and another, headed by Ricardo Flores Magón, in the border city of Laredo.

Diaz agents backed by US authorities chased liberals in Texas, so they continued to move further and further north. On 28 September 1905, in Saint Louis, Missouri, United States, the Magón Flores group drafted the manifesto with which the Organizing Board of the Mexican Liberal Party was constituted. The tasks of the Organizing Board were to summon and articulate all the opposing forces to prepare the fight against the dictator.

On 1 July 1906, after almost a year of discussion on the political, economic and social situation of the country, the Manifesto and Program of the Mexican Liberal Party was published. Among the main policies of the program were the eight-hour day, prohibition of child labor, minimum wage, compensation for accidents at work, compulsory and free secular education. Years later, these policies presented by the PLM in this program formed the basis of the 1917 Constitution of Mexico, which officially ended the Mexican Revolution.

Strikes and insurrections

[edit]The PLM organized several uprisings against the Porfirio Díaz regime, all of which were violently repressed. The PLM Program influenced the Cananea strike, and Río Blanco strike, as well as the Acayucan rebellion.

On 16 September, the PLM initiated their revolutionary plan. When the groups operating in the United States took over the main border customs and reinforced the supply of weapons, the 44 guerilla groups (totalling 2200 fighters) all over the republic would rise up in arms. However most of the liberals were discovered by the US police, who seized weapons and documents that discovered the insurrection plans, so it had to be postponed. 26 September was set as the new date to start the Revolution. A group of liberals attacked Jiménez but after a few hours federal forces arrived, outnumbering and forcing them to flee. Other attacks were carried out in Monclova, Zaragoza, Piedras Negras and other small towns in Coahuila, to similar results.

On 30 September, the Acayucan rebellion began, led by Hilario C. Salas and Cándido Donato Padua, PLM delegates from Veracruz and Tabasco. In Acayucan the clashes against the army lasted 4 days. Most of the rebels died, some fled to the Soteapan mountain range where they reorganized the guerrilla war, continuing the fight until 1911.

On 16 October, a third insurrectional attempt was made in Camargo, which was also defeated. On 19 October, the group from El Paso, organized by Ricardo Flores Magón, ventured into Ciudad Juarez, but were discovered crossing the border by federal soldiers, who were already aware of the uprising. The next day the rest of the insurgents were arrested in El Paso by immigration agents and Pinkerton detectives, but Magón managed to escape.

On 24 June 1908 the PLM attacked Viesca, but were repelled and defeated. The leaders were apprehended and sent to the political prison of San Juan de Ulúa in Veracruz. On 26 June, the liberals attacked Acuña, Casas Grandes and Palomas. There was also belligerent PLM activity in Oaxaca, Puebla, Tlaxcala and Morelos. The railroad strike that paralyzed the northern part of the country that year was also influenced by the PLM.

A Pinkerton agent in St. Louis declared that, in 1908, 180 members of the PLM had been arrested and placed in Mexican prisons, so "the danger of a revolution had passed".[15] But in 1909, Práxedis G. Guerrero published a series of manifestos aimed at the workers of the world, and urged Mexicans to rise up in rebellion. The most effective weapon of the PLM was the press. Even in exile, it had at least 7 publications in different locations, all of which were gradually suppressed by the authorities.[16]

The Mexican Libertarian Army

[edit]

For the Mexican Liberal Party, simply overthrowing dictator Porfirio Díaz wasn't enough if it did not guarantee communal freedom. They understood that the struggle for political freedom was useless if economic freedom didn't come with it, so in order to guarantee that freedom it would be necessary to take and defend the land in an armed rebellion. The armed groups of the PLM were organized into the Liberal Army Confederation, also known as the Mexican Libertarian Army.

On 23 September 1910, the PLM Organizing Board in Los Angeles published, in Regeneration, a libertarian manifesto that called on Mexicans to fight against the State, the Clergy and Capital, under the slogan "Land and Freedom", an ideal that a month later was taken up by Emiliano Zapata.

The most important military campaign of the Mexican Liberal Army was the Baja Revolution. Mexicans and volunteers of other nationalities participated in this anarchist and socialist revolution; reason that gave rise to the authorities intensifying their repression of the PLM. By refusing to recognize the Treaties of Ciudad Juárez, the PLM guerrillas were persecuted and exterminated by the federal army and Maderist groups during the provisional government of Francisco León de la Barra, who requested support from the United States government to transfer Mexican troops through American territory and attack the Baja revolution on two fronts.

The military campaigns of the PLM, failed again and again due to the lack of resources, police infiltration and confusion caused by counterproductive tactics. Although for some, Maderism represented the most viable political alternative; for others, supporting Madero was simply the only way to escape alive from Mexican prisons. However, there were others who preferred jail or death to betraying their ideals.[17]

Final years

[edit]After the raid on Baja California, and with Ricardo Flores Magón, Librado Rivera and Anselmo Figueroa in jail, there were other armed uprisings on behalf of the PLM. Such was the case of Primitivo Gutiérrez who on 9 February 1912, on behalf of the PLM, repealed the Constitution and declared anarchist communism in the town of Las Vacas, Coahuila.[18] In 1913 PLM groups attempted to launch themselves back into the armed struggle. While attempting to enter Mexico from Texas, they faced a group of rangers, were defeated and sentenced to 50 years or more of prison.[19] However, these actions had no major impact on the development of events in Mexico, the PLM's role in the Mexican Revolution drew to a close.

In 1915, after the death of Anselmo L. Figueroa and the lack of resources to continue Regeneration, a small group of the PLM moved to a farm located in Edendale, Los Angeles. There they lived and worked communally, raised chickens and grew vegetables that they sold for support, while carrying out the political work of the PLM, now renamed the Revolutionary Workers Union (UOR).[20]

In February 1916, Enrique and Ricardo Flores Magón were arrested at their home in Edendale, accused of defaming Venustiano Carranza. They were released months later, when a committee promoted by Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman collected the bail money demanded by the Los Angeles court. Shortly after leaving prison, Enrique Flores Magón left the UOR, along with most others. Librado Rivera and Ricardo Flores Magón remained, and together they published a manifesto in Regeneration addressed to anarchists of the world. In 1918, they were arrested, accused of conspiracy by the United States government, and sentenced to 15 and 20 years in prison respectively.

Flores Magón died in prison in 1922. Rivera was released and deported to Mexico where he continued denouncing the governments emanating from the revolution, he was imprisoned during the mandate of Plutarco Elías Calles and died in 1932.

Legacy

[edit]The PLM slogan "Tierra y Libertad" (Land and Liberty) also appeared in the group's Regeneración newspaper illustrations. Ricardo Flores Magón used it as the title of a play and William C. Owen used it as the title of an American anarchist newspaper.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ricardo Flores Magón – El Apóstol cautivo, tomo I, cap. 9 – El Partido Liberal Mexicano Archived 17 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine [Currently not working, use the reference below] Government of Mexico (in Spanish)

- ^ Ricardo Flores Magón – El Apóstol cautivo, tomo I, cap. 9, pg. 166 – El Partido Liberal Mexicano Library of the Department of Historic Investigations (in Spanish)

- ^ Hodges, Donald C. (2010). Mexican Anarchism after the Revolution. University of Texas Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-292-78875-6.

- ^ Bosque Lastra, Margarita (1997). La constitución de hoy y su protección hacia el siglo XXI. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. p. 132.

- ^ Suárez Cortina, Manuel (2013). Cuestión religiosa España y México en la época liberal. Ediciones Universidad Cantabria. pp. 218–219.

- ^ Córdova, Arnaldo (1973). La ideología de la Revolución Mexicana la formación del nuevo régimen. Ediciones Era. p. 122.

- ^ Buchenau, Jürgen (3 September 2015). "The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1946". Latin American History: 2. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.21. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9.

- ^ Ward Albro, "Always a Rebel" 1992, p8

- ^ Ward Albro, "Always a Rebel" 1992, p10

- ^ Ward Albro, "Always a Rebel" 1992, p10

- ^ Ward Albro, "Always a Rebel" 1992, p8

- ^ Ward Albro, "Always a Rebel" 1992, p13

- ^ Ward Albro, "Always a Rebel" 1992, p30

- ^ John Lear – Workers, Neighbors, and Citizens: The Revolution in Mexico City. Political cultures and movilization – Maderista politics

- ^ Ricardo Flores Magón: una vida en rebeldía, Salvador Hernández Padilla, September 2003

- ^ Cockcroft, D. James; Barrales, María Eunice (1971). Precursores intelectuales de la Revolución Mexicana(1900–1913). Siglo XXI. ISBN 968-23-1631-6. p. 146.

- ^ Hernández Padilla, Salvador (1984). El Magonismo: Historia de una pasión libertaria 1900–1922. Ediciones Era. ISBN 968-411-199-1. p. 193-194.

- ^ Regeneración Tomo IV, No. 77. Los Ángeles, California.17 de febrero de 1912. Archivo Electrónico Ricardo Flores Magón.

- ^ This group of condemned PLM members were known as "The Martyrs of Texas." Notes on a letter from Flores Magón to lawyer Harry Weinberger, defender of Flores Magón and the Martyrs of Texas. Kansas, 1920. Upon his return to Mexico, Librado Rivera wrote the book "Los Martires de Texas", in favor of the freedom of his fellow prisoners.

- ^ Hernández Padilla, Salvador. op. cit., p. 197.

- ^ Streeby, Shelley (8 February 2013). Radical Sensations: World Movements, Violence, and Visual Culture. Duke University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8223-9554-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Ricardo Flores Magón: Dreams of Freedom : A Ricardo Flores Magón Reader, Ak Press, 2005, ISBN 1-904859-24-0

- Javier Torres Pares: La revolucion sin frontera: El Partido Liberal Mexicano y las relaciones entre el movimiento obrero de Mexico y el de Estados Unidos, 1900–1923, Ediciones y Distribuciones Hispanicas, 1990, ISBN 968-36-1099-4

- Juan Gomez-Quiñones: Sembradores: Ricardo Flores Magón y el Partido Liberal Mexicano: A Eulogy and Critique, 1973, Chicano Studies Center Publications, ISBN 0-89551-010-3

- Jeffrey Kent Lucas, The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7734-3665-7.

- 1905 establishments in Mexico

- 1918 disestablishments in North America

- Anarchist political parties

- Anarcho-communism

- Communist parties in Mexico

- Defunct anarchist organizations in North America

- Defunct political parties in Mexico

- Far-left politics in Mexico

- Jacobinism

- Left-wing populism

- Magonism

- Political parties established in 1905

- Political parties disestablished in 1918

- Radical parties