Paris by Night

| Paris by Night | |

|---|---|

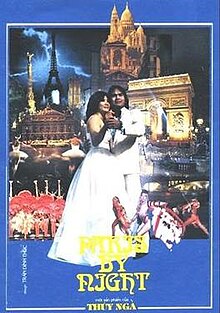

VHS cover of first show | |

| Genre | Variety show |

| Created by | Tô Văn Lai |

| Presented by | Nguyễn Ngọc Ngạn Nguyễn Cao Kỳ Duyên |

| Country of origin | United States Canada France |

| Original languages | Vietnamese English (occasionally) French (occasionally) |

| No. of episodes | 135 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Executive producers | Marie Tô Paul Huỳnh |

| Producer | John Nguyen (coordinator) |

| Production location | (see Venues section of article) |

| Running time | Originally up to two hours, now up to five hours |

| Production company | Thúy Nga |

| Original release | |

| Release | 1983 – present |

Paris by Night (commonly abbreviated as PBN) is a direct-to-video series featuring Vietnamese-language musical variety shows produced by Thúy Nga Productions. Hosted mainly by Nguyễn Ngọc Ngạn and Nguyễn Cao Kỳ Duyên, the series includes musical performances by modern pop stars, traditional folk songs, one-act plays, and sketch comedy.[1]

Background

[edit]Paris By Night was conceived by immigrant Tô Văn Lai in 1983, in Paris, France, to "fill the cultural void" felt by Vietnamese refugees living in France. Shortly afterwards, the show's production company transferred to Orange County, California, which has a larger Vietnamese community.[2]

Themes

[edit]The show is set up with "melodramatic performances, catchy pop tunes, Vaudeville-esque comedy, and elaborate set designs", with a large emphasis of production focusing on expressing Vietnamese culture. In recent years, the rising popularity of K-pop and J-pop has applied creative pressure to Thúy Nga CEO Marie Tô, who responded by insisting on keeping with the Vietnamese style, commenting "Of course, K-pop is very big now…but we kind of want to create our own image. The singer[s] we produce, we want to create their image—not imitating K-pop or anything." The show has since been noted as not only a form of entertainment, but a "way to connect to a larger identity".[3]

Production

[edit]Crew

[edit]While most of the staff and crew remain the same from show to show, the directors may vary based on the filming location. Richard Valverde served as director for shows in Paris, Michael Watt directed shows in Canada and the United States, and Victor Fable directed in the United States. Notable directors include The Voice's Alan Carter, who directed six shows in the United States, CEO of production company A. Smith & Co. Kent Weed, of six shows in the United States, and NBC director Ron de Moraes, who directed five shows.

| Director | PBN Shows Directed |

|---|---|

| Jean Pierre Barry | 10 - 15 |

| Richard Valverde | 16 - 37; 53 - 54; 60 - 62; 65 - 66; 69 - 70; 134; 136 |

| Pascal Cresegut | 23 |

| Michael Watt | 38 - 50; 56; 58 - 59; 72 - 87; 91 |

| Lưu Huỳnh | 49 |

| Đinh Anh Dũng | 49 |

| Christian Oshea | 52 |

| Kent Weed | 57; 63 - 64; 67 - 68; 71; |

| Danielle Phương Thảo | 59 |

| Alan Carter | 88; 90; 92 - 99; Divas; 100 - 106; 108; 111; 120; 123; 129 |

| Seounghyun Oh | 89 |

| Ron de Moraes | 107; 109 - 110; 112; 114 - 119; 124; 126 - 128 |

| Ken Nguyễn | PBN VIP Parties; 113; 121 - 122; Divos; Gloria 1 - 3; 125; 131; 135 |

| Manuel Bonilla | 130; 132 - 133; 137 |

Starting with Paris by Night 34: Made in Paris, Shanda Sawyer worked as the production's main choreographer.

Filming

[edit]Originally, Paris by Night was filmed exclusively in Paris, with its intended target audience consisting of the Vietnamese population in France. However, by the late 1980s, the production moved to Orange County, California following demand from the more populous Vietnamese American community for the production to host shows in the United States and the fact that most Vietnamese language performers from the former South Vietnam lived in the country, with filming beginning in the country in the mid-1990s.[4]

Except for several tapings, Paris by Night has been filmed live before an audience. The show has since been filmed in France, the United States, Canada, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand. It has never been filmed in Vietnam.[3][5]

Video release

[edit]Since the beginning of the show's run, the producers have been releasing videos of the shows on VHS and, more recently, DVD. Since the digital age, however, Paris by Night sales have dropped significantly, and the company has since switched to a video on demand service and subscription services similar to Netflix. Full shows and music clips have been made on the official Thúy Nga YouTube channel, supported with ad revenue. The company has also allowed IP addresses in Vietnam to stream shows for free,[3] countering the country's ban on the show's sales. Production coordinator John Nguyen states “All the copies in Vietnam are bootleg or through illegal downloads."[2]

Venues

[edit]This is a partial list of the venues and locations used in Paris By Night:

| Studio/Theatre/Venue | City | State/Province | Country | PBN Shows Produced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taratata Studio, Euromedia France | Paris | Île-de-France | France | PBN 01 - 23, 25 - 28, 30, 31, 33 - 35, 48, 51, 53, 54, 60, 61, 65 & 66 |

| Cerritos Center for The Performing Arts | Cerritos | California | United States | PBN 24 |

| Caesars Palace | Paradise | Nevada | United States | PBN 29 & 37 |

| Shrine Auditorium | Los Angeles | California | United States | PBN 32 |

| Houston Music Hall | Houston | Texas | United States | PBN 36 |

| CBC Studio 40, Canadian Broadcasting Centre | Toronto | Ontario | Canada | PBN 38, 39, 41, 43 - 45, 47, 49, 56, 58, 59, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 82, 85 |

| John Bassett Theatre, Metro Toronto Convention Centre | Toronto | Ontario | Canada | PBN 42, 50 |

| Terrace Theatre, Long Beach Performing Arts & Convention Center | Long Beach | California | United States | PBN 46, 52, 57, 73, 77, 81, 90, 91, 94, 95 |

| Théâtre de l'Empire | Paris | Île-de-France | France | PBN 62 |

| Charles M. Schulz Theater, Knott's Berry Farm | Buena Park | California | United States | PBN 63, 64, 68, 83, 86, 87, 92, 93, 96, 97, 99, 102 & 103 |

| San Jose Center for the Performing Arts | San Jose | California | United States | PBN 67, 71, 75 & 79 |

| Studio Carrere | Paris | Île-de-France | France | PBN 69 & 70 |

| Atlanta Civic Center | Atlanta | Georgia | United States | PBN 84 |

| Hobby Center for the Performing Arts | Houston | Texas | United States | PBN 88 |

| Olympic Fencing Gymnasium, Seoul Olympic Park | Seoul | Seoul Capital Area | South Korea | PBN 89 |

| Zappos Theater, Planet Hollywood Las Vegas | Paradise | Nevada | United States | PBN 98, 100, 104, 106, 109, 111, 115, 123, 128 & 129, 133 |

| Pechanga Showroom Theater, Pechanga Resort & Casino | Temecula | California | United States | PBN 101, 107, 110, 112, 114, 116 - 119, 121, 122, 124, 127, 132, 135, 137 |

| MGM Grand Theater, Foxwoods Resort Casino | Ledyard | Connecticut | United States | PBN 56, 105, 108 |

| Saigon Performing Arts Center | Fountain Valley | California | United States | PBN 113, 125 |

| Choctaw Casino & Resort | Durant | Oklahoma | United States | PBN 120 |

| Mystic Lake Casino | Prior Lake | Minnesota | United States | PBN 126 |

| Resorts World Sentosa | Sentosa | Sentosa Island | Singapore | PBN 130 |

| Premiere Studio | Fountain Valley | California | United States | PBN 131 |

| Royal Paragon Hall, Siam Paragon | Bangkok | Bangkok | Thailand | PBN 134, 136 |

Demographics

[edit]When first produced in the 1980s, the show was made for Vietnamese people who had been living in France in the 1960s and 1970s. However, the show found a larger audience in the United States by the late 1980s. As a result of the digital age of the 21st century, the show has become more readily accessible online. According to Thúy Nga, the main demographic of the shows consisted of people under the age of 40.[3] Presenter Nguyễn Cao Kỳ Duyên commented on the show's popularity in Vietnam, noting "We actually give the Vietnamese audience in Vietnam a very high level of entertainment unmatched by what they have now."[2]

Controversies

[edit]As an overseas Vietnamese production and classified as a "reactionary cultural product" by the Vietnamese government, Paris by Night cannot be legally purchased in Vietnam, although unauthorized copies can be easily obtained in the black market. It sometimes features performances that are related to historical events, critical of the ruling Vietnamese Communist Party. In 2004, in Paris by Night 74, Hoang Oanh sang a song about Operation Passage to Freedom and a video montage was shown depicting beleaguered-looking northern Vietnamese fleeing to the anti-communist south during the partition of Vietnam, where they were met by Ngô Đình Diệm and his government's officials. This performance coincided with the 50th anniversary of the migration. In 2005, Paris by Night 77 was devoted to the 30-year anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, and included songs explicitly critical of communist rule, lack of human rights, accompanied by montages of the closing stages of the Ho Chi Minh Campaign, the flight of distressed anti-communist refugees, and interpretative dancing critical of VCP rule, such as throat-slitting gestures. It also included documentary segments on the progress of Vietnamese immigrant communities since 1975, including one segment praising American support for South Vietnam and Operation Babylift—the communist government views the babylift of orphans as "abduction"—and gave awards to Vietnamese humanitarians and American political officials who helped Vietnamese refugees, as well as the Republic of Vietnam Air Force fighter pilot Nguyễn Qúy An.

In Paris by Night 91, for the 40th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, one medley involved Quang Lê singing about the beauty of the former Huế, backed by female dancers, before an explosion knocks them and the bridge over the Perfume River to the ground, something perpetrated by the communists during the Battle of Huế during the Tet Offensive. Khánh Ly then proceeded to sing Trịnh Công Sơn's "Song for dead bodies" about the communist massacre at Huế, which killed thousands. A video montage of the massacre, inconsolable relatives and the subsequent exhumation and religious reburial was shown in the background during Khanh Ly's performance.

It is also the subject of some controversies among the overseas Vietnamese population due to what some perceive as its support of the current government of Vietnam. Paris by Night 40, with the topic of motherhood, featured a song by the composer Trịnh Công Sơn titled "Ca Dao Mẹ", which was performed by Don Hồ. The song included a reenactment of a bombing during the Vietnam War and showed a mother grieving over the death of her child and her husband. Some were offended by the song's antiwar message while others see this as an indictment against American and South Vietnamese troops even though the scene did not make it clear which side was doing the bombing. After a boycott, Thúy Nga reissued Paris by Night 40 with the bombing scenes removed. Paris by Night 40 is the most commercially successful production.[6] The director of the segment, Lưu Huỳnh, later went on to direct The White Silk Dress in Vietnam, a film with similar themes.

In Paris by Night 96, Thúy Nga Productions's Nguyễn Ngọc Ngạn wrote a skit about a Vietnamese American gay kid, starring Bang Kieu. This sparked conversations among Vietnamese American parents and their gay children. It helped build more tolerance for the Vietnamese American LGBT community overseas. This shows the company's cultural influence over the Vietnamese American culture, experience and audience.

There has also been increasing recent criticism of the production over-Americanizing its shows, with traditional Vietnamese culture and aspects no longer being emphasized as before, as well as the production largely losing its original French cabaret influence and roots. In fact, Paris by Night has not been filmed in its namesake city since 2003, Paris by Night 70.

Recurring performers

[edit]Male

[edit]- Bằng Kiều

- Don Hồ

- Dương Triệu Vũ

- Lâm Nhật Tiến

- Luong Tung Quang

- Nguyễn Ngọc Ngạn

- Quang Lê

- Roni Trọng

- Thanh Bùi

- Thế Sơn

- Tommy Ngô

- Tuấn Ngọc

- Trường Vũ

- Mạnh Quỳnh

- Trần Thái Hòa

- Nguyễn Hưng

- Trịnh Lam

- Mai Tiến Dũng

- Đan Nguyễn

- Hoài Lâm

- Ngoc Ngu

- Tuấn Vũ

- Tuấn Phước

Female

[edit]- Ái Vân

- Ánh Minh

- Diễm Liên

- Hồ Lệ Thu

- Hương Lan

- Hương Thủy

- Khánh Ly

- Lâm Thúy Vân

- Lynda Trang Đài

- Loan Châu

- Minh Tuyết

- Nguyễn Cao Kỳ Duyên

- Như Loan

- Như Quỳnh

- Tâm Đoan

- Thanh Hà

- Thủy Tiên

- Tóc Tiên

- Trần Thu Hà

- Mai Thiên Vân

- Quỳnh Vi

- Hạ Vy

- Diễm Sương

- Như Ý

- Myra Trần

- Hoàng Mỹ An

- Hoàng Nhung

- Châu Ngọc Hà

- Phương Yến Linh

- Hoàng Oanh

- Thanh Tuyền

- Phương Hồng Quế

References

[edit]- ^ "We'll Always Have Paris By Night". San Francisco Weekly. 2010-06-23. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- ^ a b c "For Vietnamese, 'Paris By Night' is a mix of Vegas, nostalgia and pre-war culture". Public Radio International. 2014-02-10. Retrieved 2014-05-31.

- ^ a b c d Nguyen, Michael (2015-11-12). "A Decades-Old Vietnamese Variety Show Goes Digital". NBC News. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- ^ Karim, Karim Haiderali (2003). The Media of Diaspora. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780415279307. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ^ "Paris By Night 130 in Singapore - November 23 & 24, 2019". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- ^ Nguyen, Mimi Thi (2007). Alien Encounters. Duke University Press. pp. 203. ISBN 9780822339229. Retrieved 2019-05-29.