Pakicetus

| Pakicetus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of P. attocki, Canadian Museum of Nature | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | †Pakicetidae |

| Genus: | †Pakicetus Gingerich & Russell 1981 |

| Type species | |

| †Pakicetus inachus | |

| Species | |

| |

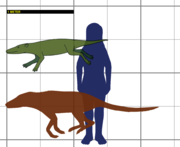

Pakicetus (meaning "whale from Pakistan") is an extinct genus of amphibious cetacean of the family Pakicetidae, which was endemic to Indian Subcontinent during the Ypresian (early Eocene) period, about 50 million years ago.[2] It was a wolf-like mammal,[3] about 1–2 m (3 ft 3 in – 6 ft 7 in) long,[4] and lived in and around water where it ate fish and other animals. The name Pakicetus comes from the fact that the first fossils of this extinct amphibious whale were discovered in Pakistan. The vast majority of paleontologists regard it as the most basal whale, representing a transitional stage between land mammals and whales. It belongs to the even-toed ungulates with the closest living non-cetacean relative being the hippopotamus.[3]

Description

[edit]Based on the sizes of specimens, and to a lesser extent on composite skeletons, species of Pakicetus are thought to have been 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in length.[4]

Pakicetus looked very different from modern cetaceans, and its body shape more resembled those of land-dwelling hoofed mammals. Unlike all later cetaceans, it had four fully functional long legs. Pakicetus had a long snout; a typical complement of teeth that included incisors, canines, premolars, and molars; a distinct and flexible neck; and a very long and robust tail. As in most land mammals, the nose was at the tip of the snout.[5]

Reconstructions of pakicetids that followed the discovery of composite skeletons often depicted them with fur; however, given their relatively close relationships with hippos, they may have had sparse body hair.[4]

The first fossil found consisted of an incomplete skull with a skull cap and a broken mandible with some teeth. Based on the detail of the teeth, the molars suggest that the animal could rend and tear flesh. Wear, in the form of scrapes on the molars, indicated that Pakicetus ground its teeth as it chewed its food. Because of the tooth wear, Pakicetus is thought to have eaten fish and other small animals. The teeth also suggest that Pakicetus had herbivorous and omnivorous ancestors.[4]

Palaeobiology

[edit]Possible semi-aquatic nature

[edit]It was illustrated on the cover of Science as a semiaquatic, vaguely crocodile-like mammal, diving after fish.[6]

Somewhat more complete skeletal remains were discovered in 2001, prompting the view that Pakicetus was primarily a land animal about the size of a wolf. Thewissen et al. 2001 wrote that "Pakicetids were terrestrial mammals, no more amphibious than a tapir."[7]

However, Thewissen et al. 2009 argued that "the orbits ... of these cetaceans were located close together on top of the skull, as is common in aquatic animals that live in water but look at emerged objects. Just like Indohyus, limb bones of pakicetids are osteosclerotic, also suggestive of aquatic habitat"[8] (since heavy bones provide ballast). "This peculiarity could indicate that Pakicetus could stand in water, almost totally immersed, without losing visual contact with the air."[9]

Sensory capabilities

[edit]The Pakicetus skeleton reveals several details regarding the creature's unique senses and provides a newfound ancestral link between terrestrial and aquatic animals. As previously mentioned, the Pakicetus' upward-facing eye placement was a significant indication of its habitat. Even more so, however, was its auditory abilities. Like all other cetaceans, Pakicetus had a thickened skull bone known as the auditory bulla, which was specialized for underwater hearing.[4] Cetaceans also all categorically exhibit a large mandibular foramen within the lower jaw, which holds a fat pack and extends towards the ear, both of which are also associated with underwater hearing. "Pakicetus is the only cetacean in which the mandibular foramen is small, as is the case in all terrestrial animals. It thus lacked the fat pad, and sounds reached its eardrum following the external auditory meatus as in terrestrial mammals. Thus the hearing mechanism of Pakicetus is the only known intermediate between that of land mammals and aquatic cetaceans."[10]

History of discovery

[edit]The first fossil, a skull fragment of P. inachus, was found in 1981 in Pakistan. Subsequent fossils of Pakicetus were also found in Pakistan, hence the generic name Pakicetus. The fossils were found in the Kuldana Formation west of Islamabad in northern Pakistan and were dated as early to early-middle Eocene in age.[11][12] The discovery of Pakicetus played an important role in solidifying the inferences that revolved around the evolution of whales.[13] The fossil indicated that whales swam up and down with their vertebral column, which caused their feet to move up and down like otters and their land movements were similar to sea lions; even their limbs protracted and retracted on land. In contrast, the origin of cetaceans, which includes whales, began as four-legged land animals who actively used locomotion and were great runners as a result.[14]

The fossils came out of red terrigenous sediments bounded largely by shallow marine deposits typical of coastal environments caused by the Tethys Ocean.[15] Speculation is that many major marine banks flourished with the presence of this prehistoric whale. According to the location of fossil findings, the animals preferred a shallow habitat that neighbored decent-sized land. Assortments of limestone, dolomite, stone mud and other varieties of different coloured sands have been predicted to be a favourable habitat for Pakicetus. During the Eocene, modern day Pakistan was part of an independent island-continent off the coastal region of Eurasia, and therefore an ideal habitat for the evolution and diversification of the Pakicetidae. [citation needed]

Classification

[edit]Pakicetus was classified as an early cetacean due to characteristic features of the inner ear found only in cetaceans (namely, the large auditory bulla is formed from the ectotympanic bone only). It was recognized as the earliest member of the family Pakicetidae. Thus, Pakicetus represents a transitional taxon between extinct land mammals and modern cetaceans.[11]

Gingerich & Russell 1981 believed Pakicetus to be a mesonychid. However, studies from molecular biology placed today's cetaceans within the group of artiodactyls, to which the mesonychids do not belong.[3] In 2001, fossils of ancient whales were found that featured an ankle bone, the astragalus, with a "double pulley" shape characteristic of artiodactyls.[3] The redescription of the primitive, semi-aquatic small deer-like artiodactyl Indohyus, and the discovery of its cetacean-like inner ear, simultaneously put an end to the idea that whales were descended from mesonychids, while demonstrating that Pakicetus, and all other cetaceans, are artiodactyls.[16]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Bajpai, S.; Gingerich, P. D. (22 December 1998). "A new Eocene archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) from India and the time of origin of whales". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (26): 15464–15468. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9515464B. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15464. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 28065. PMID 9860991.

- ^ a b Thewissen et al. 2009.

- ^ a b c d Black, Riley (1 December 2010). "How Did Whales Evolve?". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ a b c d e Geisler, Jonathan; Ho, Melody. "Pakicetus spp". Cetacean Family Tree. NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine. Archived from the original on 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ^ Marx, Felix; Lambert, Oliver; Uhen, Mark (2016). Cetacean Paleobiology. Topics in Paleobiology (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1118561270.

- ^ Gingerich et al. 1983, Cover

- ^ Thewissen et al. 2001, p. 278

- ^ Thewissen et al. 2009, p. 277.

- ^ de Muizon 2009.

- ^ Thewissen & Hussain 1993

- ^ a b Gingerich & Russell 1981.

- ^ Cooper, Thewissen & Hussain 2009.

- ^ Gingerich et al. 1983.

- ^ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Hussain, S. T.; Arif, M. (1994). "Fossil Evidence for the Origin of Aquatic Locomotion in Archaeocete Whales". Science. 263 (5144): 210–212. Bibcode:1994Sci...263..210T. doi:10.1126/science.263.5144.210. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 2882378. PMID 17839179. S2CID 20604393.

- ^ Gingerich 2003a.

- ^ Holmes, Bob (8 October 2014). "A life spent chasing down how whales evolved". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2015-11-05. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

References

[edit]- Polly, Paul D. "Pakicetus (fossil Mammal Genus)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- Cooper, Lisa Noelle; Thewissen, J. G. M.; Hussain, S. T. (2009). "New middle Eocene archaeocetes (Cetacea: Mammalia) from the Kuldana Formation of northern Pakistan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1289–1299. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1289C. doi:10.1671/039.029.0423. S2CID 84127292.

- de Muizon, Christian (March 2009). "L'origine et l'histoire évolutive des Cétacés" [Origin and evolutionary history of cetaceans]. Comptes Rendus Palevol (in French). 8 (2–3): 295–309. Bibcode:2009CRPal...8..295D. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2008.07.002.

- Gingerich, Philip D.; Wells, N. A.; Russell, Donald E.; Shah, S. M. Ibrahim (22 April 1983). "Origin of Whales in Epicontinental Remnant Seas: New Evidence from the Early Eocene of Pakistan" (PDF). Science. 220 (4595): 403–406. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..403G. doi:10.1126/science.220.4595.403. PMID 17831411. S2CID 37602424. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Gingerich, Philip D.; Russell, Donald E. (1981). "Pakicetus inachus, A New Archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Early-Middle Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat (Pakistan)" (PDF). Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, the Museum of Michigan. 25 (11): 235–246. OCLC 742729300. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- Gingerich, Philip D. (2003a). "Land-to-sea transition in early whales: evolution of Eocene Archaeoceti (Cetacea) in relation to skeletal proportions and locomotion of living semiaquatic mammals". Paleobiology. 29 (3): 429–454. Bibcode:2003Pbio...29..429G. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0429:LTIEWE>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86600469.

- Gingerich, Philip D. (2003b). "Stratigraphic and micropaleontological constraints on the middle Eocene age of the mammal-bearing Kuldana Formation of Pakistan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3): 643–651. Bibcode:2003JVPal..23..643G. doi:10.1671/2409. S2CID 131407382.

- Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, E. M.; Roe, L. J.; Hussain, S. T. (2001). "Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls" (PDF). Nature. 413 (6853): 277–281. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..277T. doi:10.1038/35095005. PMID 11565023. S2CID 4416684. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Thewissen, J. G. M.; Cooper, Lisa Noelle; George, John C.; Bajpai, Sunil (2009). "From Land to Water: the Origin of Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2 (2): 272–288. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0135-2.

- Thewissen, J.G.M.; Hussain, S.T. (1993). "Origin Of Underwater Hearing in Whales". Nature. 361 (6411): 444–445. Bibcode:1993Natur.361..444T. doi:10.1038/361444a0. PMID 8429882. S2CID 4319369.

- West, Robert M (1980). "Middle Eocene large mammal assemblage with Tethyan affinities, Ganda Kas region, Pakistan". Journal of Paleontology. 54 (3): 508–533. JSTOR 1304193. OCLC 4899161959.