Second Italo-Senussi War

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Second Italo-Senussi War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the interwar period | |||||||

Senussi rebel leader Omar al-Mukhtar (the man in traditional clothing with a chain on his left arm) after his arrest by Italian armed forces in 1931. Mukhtar was executed in a public hanging shortly afterward. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,582 deaths[2] | 40,000–70,000 deaths[3] | ||||||

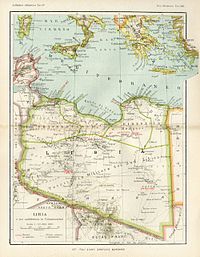

The Second Italo-Senussi War, also referred to as the Pacification of Libya, was a conflict that occurred during the Italian colonization of Libya between Italian military forces (composed mainly by colonial troops from Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia)[4] and indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi Order. The war lasted from 1923 until 1932,[5][6][7] when the principal Senussi leader, Omar al-Mukhtar, was captured and executed.[8] The Libyan genocide took place during and after the conflict.

| Events leading to World War II |

|---|

Fighting took place in all three of Libya's provinces (Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica), but was most intense and prolonged in the mountainous Jebel Akhdar region of Cyrenaica.[9] The war led to the mass deaths of the indigenous people of Cyrenaica, totalling one quarter of the region's population of 225,000.[10] Italian war crimes included the use of chemical weapons, execution of surrendering combatants, and the mass killing of civilians,[1] while the Senussis were accused of torture and mutilation of captured Italians and refusal to take prisoners since the late 1910s.[11][12][13] Italian authorities forcibly expelled 100,000 Bedouin Cyrenaicans, half the population of Cyrenaica, from their settlements, many of which were then given to Italian settlers.[14][15]

Background

[edit]Italy had seized military control of Libya from the Ottoman Empire during the Italo-Turkish War in 1912,[16] but the new colony had swiftly revolted, transferring large swaths of territory to local Libyan rule.[17] Conflict between Italy and the Senussis – a Muslim political-religious tariqa based in Libya – erupted into major violence during World War I, when Senussis in Libya began collaborating with the Ottomans against Italian troops. The Libyan Senussis also escalated the conflict by attacking British forces stationed in Egypt.[18] Conflict between the British and the Senussis continued until 1917.[19]

In 1917, an exhausted Italy signed the Treaty of Acroma, which acknowledged the effective independence of Libya from Italian control.[20] In 1918, Tripolitanian rebels founded the Tripolitanian Republic, though the rest of the country remained under nominal Italian rule.[20] Local resistance against Italy continued, such that by 1920, the Italian government was forced to recognize Senussi leader Sayid Idris as Emir of Cyrenaica and grant him autonomy.[20] In 1922, Tripolitanian leaders offered Idris the position of Emir of Tripolitania;[20] however, before Idris could accept the position, the new Italian government of Benito Mussolini initiated a campaign of reconquest.[20][21]

Since 1911, claims had been made of killings of Italian soldiers and civilians by Ottoman and local Muslim guerrillas, such as a slaughter in Sciara Sciat:[22]

I saw (in Sciara Sciat) in one mosque seventeen Italians, crucified with their bodies reduced to the status of bloody rags and bones, but whose faces still retained traces of their hellish agony. Long rods had been passed through the necks of these wretched men and their arms rested on these rods. They were then nailed to the wall and died slowly with untold suffering. It is impossible for us to paint the picture of this hideous rotted meat hanging pitifully on the bloody wall. In a corner another body was crucified, but as an officer he was chosen to experience refined sufferings. His eyes were stitched closed. All the bodies were mutilated and castrated; so indescribable was the scene and the bodies appeared swollen as shapeless carrion. But that's not all! In the cemetery of Chui, which served as a refuge from the Turks and to whence soldiers retreated from afar, we could see another show. In front of one door near the Italian trenches five soldiers had been buried up to their shoulders, their heads emerged from the black sand stained with their blood: heads horrible to see and there you could read all the tortures of hunger and thirst. –– Gaston Leroud, correspondent for Matin-Journal (1917)[11]

Reports of these killings led to cries for retaliation and revenge in Italy, and in the early 1920s the rise to power of Benito Mussolini, leader of the National Fascist Party, as Prime Minister of Italy led to a much more aggressive approach to foreign policy. Given the importance that the Fascists gave to Libya as part of a new Italian Empire, this incident served as a useful pretext for large-scale military action to reclaim it.[23]

Campaign

[edit]War

[edit]

The war began with Italian forces rapidly occupying the Sirte desert separating Tripolitania from Cyrenaica. Using aircraft, motor transport and good logistical organization, the Italians were occupied 150,000 square kilometres (58,000 sq mi) of territory in five months,[25] cutting off the physical connection formerly held by the rebels between Cyrenaica and Tripolitania.[25] By late 1928, the Italians had taken control of Ghibla, and its tribes were disarmed.[25]

From 1923 to 1924, Italian troops regained all territory north of the Ghadames-Mizda-Beni Ulid region, with four-fifths of the estimated population of Tripolitania and Fezzan within the Italian area. In that period, they also regained the northern lowlands of Cyrenaica,[21] but attempts to occupy the forested hills of Jebel Akhtar were met with strong guerrilla resistance, led by Senussi sheikh Omar Mukhtar.[21]

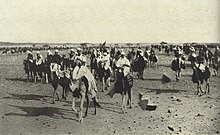

The majority of the Italian force consisted of 31,600 colonial troops from Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, along with 1900 Italian troops and about 6,000 Libyans.[26]

Attempted negotiations between Italy and Omar Mukhtar broke down and Italy then planned for the complete conquest of Libya.[27] In 1930, Italian forces conquered Fezzan and raised the Italian flag in Tummo, the southernmost region of Fezzan.[25] On 20 June 1930, Pietro Badoglio wrote to General Graziani: "As for overall strategy, it is necessary to create a significant and clear separation between the controlled population and the rebel formations. I do not hide the significance and seriousness of this measure, which might be the ruin of the subdued population...But now the course has been set, and we must carry it out to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica must perish".[28] By 1931, well over half the population of Cyrenaica were confined to 15 concentration camps where many died as result of overcrowding in combination with a lack of water, food and medicine while Badoglio had the Air Force use chemical warfare against the Bedouin rebels in the desert.[28]

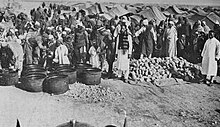

12,000 Cyrenaicans died in 1931 and all the nomadic peoples of northern Cyrenaica were forcefully removed from the region and relocated to huge concentration camps in the Cyrenaican lowlands.[27] Italian military authorities carried out the forced migration and deportation of the entire population of Jebel Akhdar in Cyrenaica, resulting in 100,000 Bedouins, half the population of Cyrenaica, being expelled from their settlements.[15] These 100,000 people, mostly women, children, and the elderly, were forced by Italian authorities to march across the desert to a series of barbed-wire concentration camp compounds erected near Benghazi, while stragglers who could not keep up with the march were shot by Italian authorities.[29] Propaganda by the Fascist regime declared the camps to be oases of modern civilization that were hygienic and efficiently run, but in reality, the camps had poor sanitary conditions, as they had an average of about 20,000 Bedouins together with their camels and other animals, crowded into an area of 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi).[29] The camps held only rudimentary medical services, with the camps of Soluch and Sisi Ahmed el Magrun with 33,000 internees each having only one doctor between them.[29] Typhus and other diseases spread rapidly in the camps as the people were physically weakened due to meagre food rations and forced labour.[29] By the time the camps closed in September 1933, 40,000 of the 100,000 total internees had already died in the camps.[29]

To close rebel supply routes from Egypt, the Italians constructed a 300-kilometre (190 mi) barbed-wire fence on the border with Egypt that was patrolled by armoured cars and aircraft.[27] The Italians persecuted the Senussi Order; zawias and mosques were closed, Senussi practices were forbidden, Senussi estates were confiscated, and preparations were made for Italian conquest of the Kufra Oasis, the last stronghold of the Senussi in Libya.[27] In 1931, Italian forces seized Kufra where Senussi refugees were bombed and strafed by Italian aircraft as they fled into the desert.[27]

In September 1931, during the Battle of Uadi Bu Taga, Mukhtar was wounded and then captured by the Libyan Savari of the Italian Army,[30] followed by a court martial and his public execution by hanging at Suluq.[27] Mukhtar's death effectively ended the resistance, and in January 1932, Badoglio proclaimed the end of the campaign.[31] Mukhtar's aides were executed later that year on 24 September 1932.[32]

Repression focus on the non-combatant population

[edit]After the failed negotiations with Omar Mukhtar, the Italian occupying power renewed its repressive policy against the Cyrenean resistance with arrests and shootings in November 1929. Since Badoglio had not gotten a grip on the guerrillas in Cyrenaica until 1930, Mussolini appointed General Rodolfo Graziani as the new lieutenant governor of Cyrenaica at the suggestion of Colonial Minister Emilio De Bono. Graziani, notorious for his firmness in fascist principles, had just completed the conquest of Fezzan and had made a name for himself as the "butcher of Fessan" in years of guerrilla warfare. Literally interpreting the regime's slogans, he understood the pacification of the country as the submission of “barbarians” to “Romans”. On 27 March 1930 Graziani moved into the Governor's Palace of Benghazi.[33] Colonial Minister De Bono regarded an escalation of violence as inevitable for the “pacification” of the region and on 10 January 1930, in a telegram to Badoglio, suggested the establishment of concentration camps (""campi di concentramento"") for the first time. Badoglio had also come to the conclusion that the "rebels" could not be permanently subjugated to the counter-guerrilla with the methods they had previously used. From then on, both appeared as pioneers and strategists in genocidal warfare within the framework defined by Mussolini, while Graziani fulfilled the role of executor.[34]

The Italians had originally divided the Libyan population into two groups, on the one hand the armed resistance "rebels", on the other hand the non-fighting, subjugated population (sottomessi), which had surrendered in the eyes of the colonial administration. In doing so, they wanted to undermine the unity of the people and act more efficiently against the armed fighters. Now, after the failure of the military offensive against the resistance movement, the Italians changed their attitude. It became clear that a clear distinction between the two groups was not possible since the resistance movement was supported both materially and morally by the "subject population". The civilians paid taxes; donated weapons, clothing or food to Omar Mukhtar's desert warriors; or made horses available to them. Since the non-combatant population ensured the reproductive conditions of the adwar system and formed the social basis of the resistance movement, they were now classified as dangerous potential by the colonial administration.[35]

During the spring and summer of 1930, Graziani systematically targeted the social environment of the guerrillas. As a first measure, he had the Islamic cultural centres (zâwiyas) closed. The Qu'ran scholars who led them were captured and deported to the Italian prison island of Ustica. Their lands were expropriated; Hundreds of houses and 70,000 hectares of prime land including the cattle on them changed hands. In addition, Graziani ordered the complete disarmament of the non-combatant population as well as draconian punishments in the event of civilians cooperating with Omar Mukhtar's adwar combat groups. Anyone who owned a weapon or provided support to the Senussi Order had to face execution. In the colonial administration, Graziani began a purge of Arab employees who were accused of treason. He had the battalions of Libyan colonial troops, which in the past often indirectly supported Omar Mukhtar's resistance, disbanded. All forms of trade with Egypt were banned in order to control the smuggling of goods to the insurgents. Last but not least, Graziani began expanding a road network in the Jebel Akhdar Mountains - a project that none of his predecessors had previously carried out. Simultaneously with these measures, a mass exodus of the Cyrenean population to the surrounding countries began.[36]

In a carefully prepared and coordinated operation with ten differently-composed columns, Graziani tried from 16 June 1930, to encircle and destroy the units of Omar Mukhtar. However, the Senussi adwar combat units were again informed in good time by the local population and by deserters from Italian colonial troops. By dividing them into smaller groups, they escaped the Italian columns with slight losses.[37]

Deportations and death marches

[edit]At this point, Badoglio took the initiative again and emphatically proposed a new dimension of repressive measures: By deporting the people of the Jabal-Achdar Mountains, he literally wanted to create an empty space around the adwar combat units. On 20 June 1930 he wrote to Graziani in a letter:

Above all, one must create a broad and precise territorial division between the rebel formations and the subjugated population. I am aware of the scope and gravity of this measure, which must lead to the annihilation of the so-called subject population. But now the way has been shown to us and we have to go to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica should perish.Mattioli (2005)

— Aram Mattioli, Experimentierfeld der Gewalt. Der Abessinienkrieg und seine internationale Bedeutung 1935–1941

After a meeting with Graziani, Badoglio ordered the complete evacuation of Jabal Achdar on 25 June 1930. Three days later, the Italian army, together with Eritrean colonial troops and Libyan collaborators, began to round up the population and their cattle. Italian archival documents date the beginning of the action to the summer of 1930. The overwhelming majority of Libyan contemporary witnesses, however, agree that the first such arrests were made in autumn 1929. Specifically, Badoglio's order resulted in the forced relocation of 100,000 to 110,000 people and their internment in concentration camps, about half of the total population of Cyrenaica. While only one report of the deportation of a single tribe is available in Italian archives, the oral history of the victims reports in detail on the extent of the action, which covered the entire area from the Marmarica region on the Egyptian border in the east to the Syrte desert in the West concerned.

However, the urban population on the coast and residents of the oases inland were not affected. From the assembly points, those who had been rounded up had to set off in columns on foot or by camels, some were also deported from the coast by ships. Such a deportation had hardly any role models in the colonial history of Africa and even put Graziani's rabid counter-guerrilla methods in the shade.[38]

Guarded by mainly Eritrean colonial troops, the entire population was forced, together with their belongings and cattle, on death marches that sometimes led over hundreds of kilometers for 20 weeks. Anyone who was picked up on the Jabal Achdar after the forced evacuation had to expect an immediate execution. In the summer heat, a considerable number of the deportees did not survive the rigors of the marches, especially children and the elderly. Anyone who fell to the ground exhausted and could no longer go on was shot by the guards. The high death rate was a deliberate consequence of the marches, and the land that was freed was again passed into the hands of colonists. Of the 600,000 camels, horses, sheep, goats and cattle that were taken on the way, only about 100,000 arrived.[39] The survivors refer to the deportation in Arabic as al-Rihlan ("path of tears").[40]

War crimes

[edit]Italian war crimes included the use of chemical weapons, execution of surrendering combatants, and killing of civilians.[1] According to Knud Holmboe tribal villages were being bombed with mustard gas by the spring of 1930, and suspects were hanged or shot in the back, with estimated thirty executions taking place daily.[41] Angelo Del Boca estimated between 40,000 and 70,000 total Libyan dead due to forced deportations, starvation and disease inside the concentration camps, and hanging and executions.[3]

Mukhtar's troops reacted with the raiding of animals and intimidation against the Libyan tribes who had submitted to the Italians, such as on November 29, 1927, when they attacked a Braasa tribe camp near Slonta, which also affected women and children.[42]

Aftermath

[edit]In 2008, Italy and Libya reached agreement on a document compensating Libya for damages caused by Italian colonial rule. Muammar Gaddafi, Libya's ruler at the time, attended the signing ceremony wearing a historical photograph on his uniform that showed Cyrenaican rebel leader Omar Mukhtar in chains after being captured by Italian authorities during the war. At the ceremony, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi declared: "In this historic document, Italy apologizes for its killing, destruction and repression of the Libyan people during the period of colonial rule." He went on to say that this was a "complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era."[43]

In popular culture

[edit]The 1936 Italian movie Lo squadrone bianco, and the 1981 Libyan film Lion of the Desert by Moustapha Akkad is about the conflict.

See also

[edit]- Battles for Murzuch

- Pacification of Algeria

- Battle and massacre at Shar al-Shatt

- Italian concentration camps in Libya

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War

- Italo-Turkish War

- Jaghbub

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Duggan, Christopher (2007). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 497.

- ^ John Gooch: Mussolini’s War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse, 1935–1943. o. O. 2020, S. 9.

- ^ a b Angelo Del Boca; Anthony Shugaar (2011). Mohamed Fekini and the Fight to Free Libya. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 9780230116337.

between 40,000 and 70,000 deaths due to forced deportations, starvation and disease inside the concentration camps, and hanging and executions

- ^ Nir Arielli (2015). "Colonial Soldiers in Italian Counter-Insurgency Operations in Libya, 1922-32". British Journal for Military History. 1 (2): 47–66.

- ^ Cooper, Tom; Grandolini, Albert (19 January 2015). Libyan Air Wars: Part 1: 1973-1985. Helion and Company. p. 5. ISBN 9781910777510.

- ^ Nina Consuelo Epton, Oasis Kingdom: The Libyan Story (New York: Roy Publishers, 1953), p. 126.

- ^ Stewart, C. C. (1986). "Islam". The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: c. 1905 – c. 1940 (PDF). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 196. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Regio Esercito - MVSN - Riconquista della Libia 1923-1931". www.regioesercito.it.

- ^ The Second Italo-Senussi War http://countrystudies.us/libya/21.htm retrvd 2-1-20

- ^ Mann, Michael (2006). The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge University Press. p. 309. ISBN 9780521538541.

- ^ a b Gaston Leroud, Matin Journal edition August 23, 1917

- ^ John Gooch (19 June 2014). The Italian Army and the First World War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-521-19307-8.

- ^ Robert Gerwarth, Erez Manela (3 July 2014). Empires at War: 1911-1923. OUP Oxford. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-100694-4.

- ^ Cardoza, Anthony L. (2006). Benito Mussolini: the first fascist. Pearson Longman. p. 109.

- ^ a b Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 358.

- ^ Martino, Antonio de] [from old catalog (27 May 1911). "Tripoli italiana, la guerra italo-turca". New York, Società libraria italiana – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Wright 1983, p. 30.

- ^ Ian F. W. Beckett. The Great War: 1914-1918. Routledge, 2013. P188.

- ^ Adrian Gilbert. Encyclopedia of Warfare: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Routledge, 2000. P221.

- ^ a b c d e Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- ^ a b c Wright 1983, p. 33

- ^ Gerwarth, Robert; Manela, Erez (3 July 2014). Empires at War: 1911-1923. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-100694-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wright 1983, pp. 32–33.

- ^ David Miller, Chris Foss. Great Book of Tanks: The World's Most Important Tanks from World War I to the Present Day. Zenith Imprint, 2003. p. 83.

- ^ a b c d Wright 1983, p. 34

- ^ Colonial soldiers in Italian Counter-Insurgency Operations in Libya 1922-32- British Journal of Military History ([1])

- ^ a b c d e f Wright 1983, p. 35

- ^ a b Grand 2004, p. 131

- ^ a b c d e Duggan 2007, p. 496

- ^ Domenico Quirico (2002). Lo squadrone bianco. Milan: Edizioni Mondadori Le Scie. p. 313.

- ^ Wright 1983, pp. 35–36

- ^ Ali Abdullatif Ahmida (2006). "When the Subaltern Speak: Memory of Genocide in Colonial Libya 1929 to 1933". Italian Studies. 61 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1179/007516306X142924. S2CID 161690236.

- ^ Ahmida 2020, pp. 59 a. 79; Gooch 2005, p. 1017; Mattioli 2004, p. 215; Wright 2012, p. 150

- ^ Gooch 2005, p. 1019; Mattioli 2004, p. 217

- ^ Abdulhakim Nagiah: Italien und Libyen in der Kolonialzeit: Faschistische Herrschaft und nationaler Widerstand. In: Sabine Frank, Martina Kamp (Hrsg.): Libyen im 20. Jahrhundert. Zwischen Fremdherrschaft und nationaler Selbstbestimmung. Hamburg 1995, S. 78; Rochat 1986, pp. 45, 47; Wright 2012, pp. 138 ff

- ^ Mattioli 2005, p. 49; Rochat 1986, pp. 69 ff

- ^ Rochat 1986, p. 71.

- ^ Ahmida 2020, pp. 3, 26, 77 & 81; Mattioli (2005), p. 49; Rochat 1986, p. 99

- ^ Ahmida 2020, pp. 61 ff; Fritz-Bauer-Institut (Hrsg.): Völkermord und Kriegsverbrechen in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 203–226, hier p. 15; Amedeo Osti Guerrazzi: Cultures of Total Annihilation? German, Italian and Japanese Armies during the Second World War. In: Miguel Alonso, Alan Kramer, Javier Rodrigo (Hg.): Fascist Warfare, 1922–1945: Aggression, Occupation, Annihilation. Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-3-030-27647-8, p. 119–142, here Sp. 125; Giulia Brogini Künzi: Italien und der Abessinienkrieg 1935/36. Kolonialkrieg oder Totaler Krieg? Paderborn u. a. 2006, p. 150; Aram Mattioli: Die vergessenen Kolonialverbrechen des faschistischen Italien in Libyen 1923–1933. In: Fritz-Bauer-Institut (Hrsg.): Völkermord und Kriegsverbrechen in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 218.

- ^ Ahmida 2020, p. 77.

- ^ Geoff Simons, Tam Dalyell (British Member of Parliament, forward introduction). Libya: the struggle for survival. St. Martin's Press, 1996. 1996 Pp. 129.

- ^ Saini Fasanotti 2012, p. 272.

- ^ Oxford Business Group (2008). The Report: Libya 2008. p. 17.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)

Sources

[edit]- Ahmida, Ali Abdullatif (6 August 2020). Genocide in Libya: Shar, a Hidden Colonial History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-16936-2.

- Grand, Alexander de (May 2004). "Mussolini's Follies: Fascism in Its Imperial and Racist Phase, 1935-1940". Contemporary European History. 13 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1017/S0960777304001602. S2CID 154458385.

- Gooch, John (2005). "Re-conquest and Suppression: Fascist Italy's Pacification of Libya and Ethiopia, 1922–39". Journal of Strategic Studies. 28 (6): 1005–1032. doi:10.1080/01402390500441024. S2CID 153977503.

- Mattioli, Aram (2004). "Die vergessenen Kolonialverbrechen des faschistischen Italien in Libyen 1923–1933.". In Fritz-Bauer-Institut (ed.). Völkermord und Kriegsverbrechen in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts (in German). Frankfurt am Main.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mattioli, Aram (2005). Experimentierfeld der Gewalt. Der Abessinienkrieg und seine internationale Bedeutung 1935–1941. Zürich.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rochat, Giorgio (1986) [1981]. "The Repression of Resistance in Cyrenaica (1927–1931)". In Santarelli, Enzo (ed.). Omar Al-Mukhtar: The Italian Reconquest of Libya. London. pp. 35–116.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wright, John (1983). Libya: A Modern History. Kent, England: Croom Helm.

- Wright, John (2012). A History of Libya. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-84904-227-7.

- Saini Fasanotti, Federica (2012). Libia 1922-1931 le operazioni militari italiane (in Italian). Rome: Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito ufficio storico.

- Interwar period

- Italian colonisation in Africa

- Italian Libya

- 1920s in Italy

- 1930s in Italy

- 1920s in Libya

- 1930s in Libya

- 1920s conflicts

- 1930s conflicts

- African resistance to colonialism

- Violence against Muslims

- Ethnic cleansing in Africa

- Genocide of indigenous peoples in Africa

- Mass murder in 1923

- Mass murder in 1932

- Senussi dynasty

- Wars involving Italy

- Italian war crimes in Libya

- Italy–Libya military relations

- Second Italo-Senussi War