Old St Paul's Cathedral

| Old St Paul's Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| History | |

| Authorising papal bull | None |

| Events | Cathedral and chanonry destroyed by fire—1087, 1666 |

| Associated people | John of Gaunt John Beauchamp John Donne |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Diocese of London (Londinium) |

| Deanery | City of London Paddington St Margaret St Marylebone |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | William Warham Edmund Bonner Edwin Sandys William Laud |

Old St. Paul's is a name used to refer to the Gothic cathedral in the City of London built between 1087 and 1314.[1] At its peak, the cathedral was the third longest church in Europe and had one of the tallest spires. The cathedral was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666, and the current domed St. Paul's Cathedral — in an English Baroque style — was subsequently erected on the site by Sir Christopher Wren.

Construction

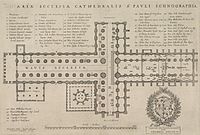

The cathedral was the fourth church on the site at Ludgate Hill dedicated to St Paul, and was begun by the Normans following a devastating fire in 1087 (detailed in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) which destroyed much of the city. Work took over 200 years, and a great deal was lost in another fire in 1136. The roof was once more built of wood, which was ultimately to doom the building. The church was consecrated in 1240, but a change of heart led to the commencement of an enlargement programme in 1256. This 'New Work' was completed in 1314 — the cathedral had been consecrated in 1300. It was the third-longest church in Europe.[2] Excavations in 1878 by Francis Penrose showed it was 586 feet (179 m) long (excluding the porch later added by Inigo Jones) and 100 feet (30 m) wide (290 feet across the transepts and crossing). The cathedral had one of Europe's tallest spires, the height of which is traditionally given as 489 feet (149 m), however, Wren judged that an overestimate and gave 460 feet (140 m)[1]. By way of comparison, the current cathedral is 574 feet (175 m) in length including the portico, and 246 feet (75 m) across the transepts.

Interior

The finished cathedral of the Middle Ages was renowned for its interior beauty. William Benham wrote in 1902: "It had not a rival in England, perhaps one might say in Europe."[1] The nave's immense length was particularly notable, with a Norman triforium and vaulted ceiling. The length earned it the nickname "Paul's walk". The stained glass was reputed to be the best in the country, and the east-end Rose window was particularly exquisite. Indeed, in The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer uses the windows as a metaphor in "The Miller's Tale".[3]

The walls were lined with the tombs of mediæval bishops and nobility. Two Anglo-Saxon kings were buried inside, Sebbi, King of the East Saxons, and Ethelred the Unready. A number of historic figures such as John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and John Beauchamp, 3rd Baron Beauchamp de Somerset had particularly large monuments constructed. The cathedral was also to later contain the tombs of the poet and clergyman John Donne and the Crown minister Nicholas Bacon.[1]

Decline

By the 16th century the building was decaying. Under Henry VIII and Edward VI, the Dissolution of the Monasteries and Chantries Acts led to the destruction of interior ornamentation and the cloisters, charnels, crypts, chapels, shrines, chantries and other buildings in the churchyard. Many of these former religious sites in St Paul's Churchyard, having been seized by the crown, were sold as shops and rental properties, especially to printers and booksellers, such as Thomas Adams, who were often evangelical Protestants. Buildings that were razed often supplied ready-dressed building material for construction projects, such as the Lord Protector's city palace, Somerset House.[2]

Crowds were drawn to the northeast corner of the Churchyard, St Paul's Cross, where open-air preaching took place. It was there in the Cross Yard in 1549 that radical Protestant preachers incited a mob to destroy many of the cathedral's interior decorations. In 1561 the spire was destroyed by lightning and it was not replaced;[4] this event was taken by both Protestants and Catholics as a sign of God's displeasure at the other faction's actions. Queen Elizabeth contributed towards the cost of repairs.[5]

England's first classical architect, Inigo Jones, added the cathedral's west front in the 1630s, but there was much defacement and mistreatment of the building by Parliamentarian forces during the English Civil War, when the old documents and charters were dispersed and destroyed and the nave was used as a stable for cavalry horses.[6]

The Great Fire

Old St Paul's was completely gutted in the Great Fire of London of 1666, which destroyed the roof and much of the stonework. Samuel Pepys recalls the building in flames in his diary:[7]

"Up by five o'clock, and blessed be God! find all well, and by water to Paul's Wharf. Walked thence and saw all the town burned, and a miserable sight of Paul's Church, with all the roof fallen, and the body of the choir fallen into St. Faith's; Paul's School also, Ludgate, and Fleet Street.

Temporary repairs were made to the building, but while it might have been salvageable, albeit with almost complete reconstruction, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style instead, a step which had been contemplated even before the fire. Following the appointment of Sir Christopher Wren, the Surveyor to the King's Works, demolition of the remains of the old cathedral began. Wren initially utilised the then-new technique of using gunpowder to bring down the surviving stone walls. Like many experimental techniques, the use of gunpowder was not easy to control and nearby residents complained about noise and damage. Eventually, Wren resorted to using a battering ram instead. Building work on the new cathedral begin in June 1675.[8]

Gallery

-

Old St. Paul's prior to 1561, with intact spire. The height depicted appears exaggerated compared to later engravings.

-

Old St Paul's Cathedral from the Thames, between 1630 and 1666

-

Old St Paul's Cathedral from the north, between 1630 and 1666

-

Old St Paul's Cathedral in flames, 1666

References

- ^ a b c d

- Benham, William (1902). Old St. Paul's Cathedral. London: Seeley & Co at Project Gutenberg

- ^ a b 1086 cathedral, St. Paul's official website, accessed 28 January 2007.

- ^

- Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Miller's Tale”, The Canterbury Tales at Project Gutenberg "His rode was red, his eyen grey as goose,

In hosen red he went full fetisly." - ^ Reynolds, H., The Churches of the City of London, London:Bodley Head, 1922

- ^ St. Paul's Cathedral timeline, URL accessed 28 January 2007.

- ^ S.E. Kelly, editor, Charters of St Paul's, London, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^

- Pepys, Samuel (1666). Diary at Project Gutenberg

- ^ 1668 — The Demolition, St. Paul's official website, accessed 30 January 2007.

External links

- Official website, with history of Old St. Paul's

- three paintings of Old St Paul's from the Society of Antiquaries (4th row down)

- History of Old St Paul's