Fossil fuel

A fossil fuel[a] is a carbon compound- or hydrocarbon-containing material[2] formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the buried remains of prehistoric organisms (animals, plants or planktons), a process that occurs within geological formations. Reservoirs of such compound mixtures, such as coal, petroleum and natural gas, can be extracted and burnt as fuel for human consumption to provide energy for direct use (such as for cooking, heating or lighting), to power heat engines (such as steam or internal combustion engines) that can propel vehicles, or to generate electricity via steam turbine generators.[3] Some fossil fuels are further refined into derivatives such as kerosene, gasoline and diesel, or converted into petrochemicals such as polyolefins (plastics), aromatics and synthetic resins.

The origin of fossil fuels is the anaerobic decomposition of buried dead organisms. The conversion from these organic materials to high-carbon fossil fuels typically requires a geological process of millions of years.[4] Due to the length of time it takes nature to form them, fossil fuels are considered non-renewable resources.

In 2022, over 80% of primary energy consumption in the world and over 60% of its electricity supply were from fossil fuels.[5] The large-scale burning of fossil fuels causes serious environmental damage. Over 70% of the greenhouse gas emissions due to human activity in 2022 was carbon dioxide (CO2) released from burning fossil fuels.[6] Natural carbon cycle processes on Earth, mostly absorption by the ocean, can remove only a small part of this, and terrestrial vegetation loss due to deforestation, land degradation and desertification further compounds this deficiency. Therefore, there is a net increase of many billion tonnes of atmospheric CO2 per year.[7] Although methane leaks are significant,[8]: 52 the burning of fossil fuels is the main source of greenhouse gas emissions causing global warming and ocean acidification. Additionally, most air pollution deaths are due to fossil fuel particulates and noxious gases, and it is estimated that this costs over 3% of the global gross domestic product[9] and that fossil fuel phase-out will save millions of lives each year.[10][11]

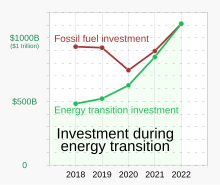

Recognition of the climate crisis, pollution and other negative impacts caused by fossil fuels has led to a widespread policy transition and activist movement focused on ending their use in favor of renewable and sustainable energy.[12] Because the fossil-fuel industry is so heavily integrated in the global economy and heavily subsidized,[13] this transition is expected to have significant economic impacts.[14] Many stakeholders argue that this change needs to be a just transition[15] and create policy that addresses the societal burdens created by the stranded assets of the fossil fuel industry.[16][17] International policy, in the form of United Nations' sustainable development goals for affordable and clean energy and climate action, as well as the Paris Climate Agreement, is designed to facilitate this transition at a global level. In 2021, the International Energy Agency concluded that no new fossil fuel extraction projects could be opened if the global economy and society wants to avoid the worst impacts of climate change and meet international goals for climate change mitigation.[18]

Origin

The theory that fossil fuels formed from the fossilized remains of dead plants by exposure to heat and pressure in Earth's crust over millions of years was first introduced by Andreas Libavius "in his 1597 Alchemia [Alchymia]" and later by Mikhail Lomonosov "as early as 1757 and certainly by 1763".[20] The first recorded use of the term "fossil fuel" occurs in the work of the German chemist Caspar Neumann, in English translation in 1759.[21] The Oxford English Dictionary notes that in the phrase "fossil fuel" the adjective "fossil" means "[o]btained by digging; found buried in the earth", which dates to at least 1652,[22] before the English noun "fossil" came to refer primarily to long-dead organisms in the early 18th century.[23]

Aquatic phytoplankton and zooplankton that died and sedimented in large quantities under anoxic conditions millions of years ago began forming petroleum and natural gas as a result of anaerobic decomposition. Over geological time this organic matter, mixed with mud, became buried under further heavy layers of inorganic sediment. The resulting high temperature and pressure caused the organic matter to chemically alter, first into a waxy material known as kerogen, which is found in oil shales, and then with more heat into liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons in a process known as catagenesis. Despite these heat-driven transformations, the energy released in combustion is still photosynthetic in origin.[24]

Terrestrial plants tended to form coal and methane. Many of the coal fields date to the Carboniferous period of Earth's history. Terrestrial plants also form type III kerogen, a source of natural gas. Although fossil fuels are continually formed by natural processes, they are classified as non-renewable resources because they take millions of years to form and known viable reserves are being depleted much faster than new ones are generated.[25][26]

Importance

Fossil fuels have been important to human development because they can be readily burned in the open atmosphere to produce heat. The use of peat as a domestic fuel predates recorded history. Coal was burned in some early furnaces for the smelting of metal ore, while semi-solid hydrocarbons from oil seeps were also burned in ancient times,[29] they were mostly used for waterproofing and embalming.[30]

Commercial exploitation of petroleum began in the 19th century.[31]

Natural gas, once flared-off as an unneeded byproduct of petroleum production, is now considered a very valuable resource.[32] Natural gas deposits are also the main source of helium.

Heavy crude oil, which is much more viscous than conventional crude oil, and oil sands, where bitumen is found mixed with sand and clay, began to become more important as sources of fossil fuel in the early 2000s.[33] Oil shale and similar materials are sedimentary rocks containing kerogen, a complex mixture of high-molecular weight organic compounds, which yield synthetic crude oil when heated (pyrolyzed). With additional processing, they can be employed instead of other established fossil fuels. During the 2010s and 2020s there was disinvestment from exploitation of such resources due to their high carbon cost relative to more easily-processed reserves.[34]

Prior to the latter half of the 18th century, windmills and watermills provided the energy needed for work such as milling flour, sawing wood or pumping water, while burning wood or peat provided domestic heat. The wide-scale use of fossil fuels, coal at first and petroleum later, in steam engines enabled the Industrial Revolution. At the same time, gas lights using natural gas or coal gas were coming into wide use. The invention of the internal combustion engine and its use in automobiles and trucks greatly increased the demand for gasoline and diesel oil, both made from fossil fuels. Other forms of transportation, railways and aircraft, also require fossil fuels. The other major use for fossil fuels is in generating electricity and as feedstock for the petrochemical industry. Tar, a leftover of petroleum extraction, is used in the construction of roads.

The energy for the Green Revolution was provided by fossil fuels in the form of fertilizers (natural gas), pesticides (oil), and hydrocarbon-fueled irrigation.[35][36] The development of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer has significantly supported global population growth; it has been estimated that almost half of the Earth's population are currently fed as a result of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer use.[37] According to head of a fertilizers commodity price agency, "50% of the world's food relies on fertilisers."[38]

Environmental effects

The burning of fossil fuels has a number of negative externalities – harmful environmental impacts where the effects extend beyond the people using the fuel. These effects vary between different fuels. All fossil fuels release CO2 when they burn, thus accelerating climate change. Burning coal, and to a lesser extent oil and its derivatives, contributes to atmospheric particulate matter, smog and acid rain.[39][40][41] Air pollution from fossil fuels in 2018 has been estimated to cost US$2.9 trillion, or 3.3% of the global gross domestic product (GDP).[9]

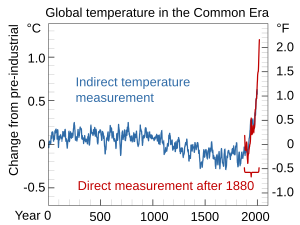

Climate change is largely driven by the release of greenhouse gases like CO2, and the burning of fossil fuels is the main source of these emissions. In most parts of the world climate change is negatively impacting ecosystems.[44] This includes contributing to the extinction of species and reducing people's ability to produce food, thus adding to the problem of world hunger. Continued rises in global temperatures will lead to further adverse effects on both ecosystems and people; the World Health Organization has said that climate change is the greatest threat to human health in the 21st century.[45][46]

Combustion of fossil fuels generates sulfuric and nitric acids, which fall to Earth as acid rain, impacting both natural areas and the built environment. Monuments and sculptures made from marble and limestone are particularly vulnerable, as the acids dissolve calcium carbonate.

Fossil fuels also contain radioactive materials, mainly uranium and thorium, which are released into the atmosphere. In 2000, about 12,000 tonnes of thorium and 5,000 tonnes of uranium were released worldwide from burning coal.[47] It is estimated that during 1982, US coal burning released 155 times as much radioactivity into the atmosphere as the Three Mile Island accident.[48]

Burning coal also generates large amounts of bottom ash and fly ash. These materials are used in a wide variety of applications (see Fly ash reuse), utilizing, for example,[clarification needed] about 40% of the United States production.[49]

In addition to the effects that result from burning, the harvesting, processing, and distribution of fossil fuels also have environmental effects. Coal mining methods, particularly mountaintop removal and strip mining, have negative environmental impacts, and offshore oil drilling poses a hazard to aquatic organisms. Fossil fuel wells can contribute to methane release via fugitive gas emissions. Oil refineries also have negative environmental impacts, including air and water pollution. Coal is sometimes transported by diesel-powered locomotives, while crude oil is typically transported by tanker ships, requiring the combustion of additional fossil fuels.

A variety of mitigating efforts have arisen to counter the negative effects of fossil fuels. This includes a movement to use alternative energy sources, such as renewable energy. Environmental regulation uses a variety of approaches to limit these emissions; for example, rules against releasing waste products like fly ash into the atmosphere.[41]

In December 2020, the United Nations released a report saying that despite the need to reduce greenhouse emissions, various governments are "doubling down" on fossil fuels, in some cases diverting over 50% of their COVID-19 recovery stimulus funding to fossil fuel production rather than to alternative energy. The UN secretary general António Guterres declared that "Humanity is waging war on nature. This is suicidal. Nature always strikes back – and it is already doing so with growing force and fury." He also claimed there is still cause for hope, anticipating the US plan to join other large emitters like China and the EU in adopting targets to reach net zero emissions by 2050.[51][52][53]

Inflation effects

Fossilflation is a term that describes the impact of fossil fuels on inflation.[54][55]

According to Vox in August 2022, "Economists have pointed to energy prices as the main reason for high inflation," noting that "energy prices indirectly affect virtually every part of the economy".[54] Sectors that raise prices significantly as a result of higher fossil fuel prices include transportation, food, and shipping.[54]

History

Mark Zandi of Moody's says that fossil fuel prices have driven every big episode of inflation since WWII.[54]

The economic impact of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was a major recent example of fossil fuels causing inflation.[55] Some economists, including Isabel Schnabel, believe that dependence on fossil fuels is the main driver of the 2021-2022 inflation spike.[54][55]

Efforts to combat fossilflation

Gernot Wagner argues that commodities are undesirable energy sources because they are susceptible to volatile price swings that technologies like renewable energy are not. He also argues that technologies improve and get relatively cheaper over time.[54][56] Coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic, some argued for the possibility of a base effect phenomenon due to cheaper than normal prices, such as for oil, at the onset of the pandemic, followed by above-average prices which exacerbated the perceived inflation.[57][58]

Inflation Reduction Act

While not expected to provide much short-term relief, the Inflation Reduction Act seeks to make the United States less dependent on fossil fuels and their ability to cause inflation in the economy.[54][59][56] Moody's estimates that by 2030, the bill could reduce the typical American household's spending on energy by more than $300 each year, in 2022 dollars.[54]

Illness and deaths

Environmental pollution from fossil fuels impacts humans because particulates and other air pollution from fossil fuel combustion may cause illness and death when inhaled. These health effects include premature death, acute respiratory illness, aggravated asthma, chronic bronchitis and decreased lung function. The poor, undernourished, very young and very old, and people with preexisting respiratory disease and other ill health are more at risk.[61] Global air pollution deaths due to fossil fuels have been estimated at over 8 million people (2018, nearly 1 in 5 deaths worldwide)[62] at 10.2 million (2019),[63] and 5.13 million excess deaths from ambient air pollution from fossil fuel use (2023).[64]

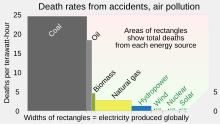

While all energy sources inherently have adverse effects, the data show that fossil fuels cause the highest levels of greenhouse gas emissions and are the most dangerous for human health. In contrast, modern renewable energy sources appear to be safer for human health and cleaner. The death rates from accidents and air pollution in the EU are as follows per terawatt-hour (TWh):

| Energy source | Nos. of deaths per TWh |

Greenhouse gas emissions (thousand tonnes/TWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Coal | 24.6 | 820 |

| Oil | 18.4 | 720 |

| Natural gas | 2.8 | 490 |

| Biomass | 4.6 | 78–230 |

| Hydropower | 0.02 | 34 |

| Nuclear energy | 0.07 | 3 |

| Wind | 0.04 | 4 |

| Solar | 0.02 | 5 |

[65] As the data shows, coal, oil, natural gas, and biomass cause higher death rates and higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions than hydropower, nuclear energy, wind, and solar power. Scientists propose that 1.8 million lives have been saved by replacing fossil fuel sources with nuclear power.[66]

Phase-out

Just transition

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: Needs to incorporate developments in international law and climate law which now recognise just transition. (September 2024) |

Divestment

Fossil fuel divestment or fossil fuel divestment and investment in climate solutions is an attempt to reduce climate change by exerting social, political, and economic pressure for the institutional divestment of assets including stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments connected to companies involved in extracting fossil fuels.[71]

Fossil fuel divestment campaigns emerged on college and university campuses in the United States in 2011 with students urging their administrations to turn endowment investments in the fossil fuel industry into investments in clean energy and communities most impacted by climate change.[72] In 2012, Unity College in Maine became the first institution of higher learning to divest[73] its endowment from fossil fuels.

By 2015, fossil fuel divestment was reportedly the fastest growing divestment movement in history.[74] As of July 2023, more than 1593 institutions with assets totalling more than $40.5 trillion in assets worldwide had begun or committed some form of divestment of fossil fuels.[75]

Divesters cite several reasons for their decisions. To some, it is a means of aligning investments with core values; to others, it is a tactic for combatting the fossil fuel industry; to others, it is a way to protect portfolios from climate-related financial risk.[76] Financial research suggests that, in the longer term, fossil fuel divestment has positively impacted investors' returns.[77][78]Industrial sector

In 2019, Saudi Aramco was listed and it reached a US$2 trillion valuation on its second day of trading,[79] after the world's largest initial public offering.[80]

Subsidies

Fossil fuel subsidies are energy subsidies on fossil fuels. Under a narrow definition, fossil fuel subsidies totalled around $1.5 trillion in 2022.[81] Under more expansive definition, they totalled around $7 trillion.[81] They may be tax breaks on consumption, such as a lower sales tax on natural gas for residential heating; or subsidies on production, such as tax breaks on exploration for oil. Or they may be free or cheap negative externalities; such as air pollution or climate change due to burning gasoline, diesel and jet fuel. Some fossil fuel subsidies are via electricity generation, such as subsidies for coal-fired power stations.

Eliminating fossil fuel subsidies would reduce the health risks of air pollution,[82] and would greatly reduce global carbon emissions thus helping to limit climate change.[83] As of 2021[update], policy researchers estimate that substantially more money is spent on fossil fuel subsidies than on environmentally harmful agricultural subsidies or environmentally harmful water subsidies.[84] The International Energy Agency says: "High fossil fuel prices hit the poor hardest, but subsidies are rarely well-targeted to protect vulnerable groups and tend to benefit better-off segments of the population."[85]

Despite the G20 countries having pledged to phase-out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,[86] as of 2023[update] they continue because of voter demand,[87][88] or for energy security.[89]Lobbying activities

The fossil fuels lobby includes paid representatives of corporations involved in the fossil fuel industry (oil, gas, coal), as well as related industries like chemicals, plastics, aviation and other transportation.[90] Because of their wealth and the importance of energy, transport and chemical industries to local, national and international economies, these lobbies have the capacity and money to attempt to have outsized influence on governmental policy. In particular, the lobbies have been known to obstruct policy related to environmental protection, environmental health and climate action.[91]

Lobbies are active in most fossil-fuel intensive economies with democratic governance, with reporting on the lobbies most prominent in Canada, Australia, the United States and Europe; however, the lobbies are present in many parts of the world. Big Oil companies such as ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, TotalEnergies, Chevron Corporation, and ConocoPhillips are among the largest corporations associated with the fossil fuels lobby.[92] The American Petroleum Institute is a powerful industry lobbyist for Big Oil with significant influence in Washington, D.C.[93][94][95] In Australia, Australian Energy Producers, formerly known as the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association (APPEA), has significant influence in Canberra and helps to maintain favorable policy settings for Oil and Gas.[96]

The presence of major fossil fuel companies and national oil companies at global forums for decision making, like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,[97] Paris Climate Agreement negotiations,[97] and United Nations Climate Change conferences has been criticised.[98] The lobby is known for exploiting international crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic,[99] or the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine,[100][101] to try to roll back existing regulations or justify new fossil fuel development.[99][100] Lobbyists try to retain fossil fuel subsidies.[102]See also

- Abiogenic petroleum origin – a proposal that petroleum is not a fossil fuel

- Bioremediation

- Carbon bubble

- Eco-economic decoupling

- Environmental impact of the energy industry

- Fossil Fools Day

- Fossil Fuel Beta

- Hydraulic fracturing

- Liquefied petroleum gas

- Low-carbon power

- Peak coal

- Peak gas

- Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles

- Shale gas

Notes

- ^ The term has been considered a misnomer because it does not actually originate from fossils, but from preserved organic matters.[1]

References

- ^ Fleckenstein, Joseph E. (2016). Three-phase electrical power. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4987-3778-4. OCLC 958799795.

- ^ "Fossil fuel". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Fossil fuels". Geological Survey Ireland. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Paul Mann, Lisa Gahagan, and Mark B. Gordon, "Tectonic setting of the world's giant oil and gas fields", in Michel T. Halbouty (ed.) Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade, 1990–1999, Tulsa, Okla.: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, p. 50, accessed 22 June 2009.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (28 November 2020). "Energy". Our World in Data.

- ^ "EDGAR - The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research". edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "What Are Greenhouse Gases?". US Department of Energy. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ "Chapter 2: Emissions trends and drivers" (PDF). Ipcc_Ar6_Wgiii. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Quantifying the Economic Costs of Air Pollution from Fossil Fuels" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2020.

- ^ Zhang, Sharon. "Air Pollution Is Killing More People Than Smoking—and Fossil Fuels Are Largely to Blame". Pacific Standard. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Lelieveld, J.; Klingmüller, K.; Pozzer, A.; Burnett, R. T.; Haines, A.; Ramanathan, V. (9 April 2019). "Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (15): 7192–7197. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.7192L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1819989116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6462052. PMID 30910976.

the potential benefits of a phaseout .... can avoid an excess mortality rate of 3.61 (2.96–4.21) million per year

- ^ Dickie, Gloria (4 April 2022). "Factbox: Key takeaways from the IPCC report on climate change mitigation". Reuters. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Price Spike Fortifies Fossil Fuel Subsidies". Energy Intelligence. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Why are fossil fuels so hard to quit?". Brookings. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "IPCC: We can tackle climate change if big oil gets out of the way". the Guardian. 5 April 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Monga, Jean Eaglesham and Vipal (20 November 2021). "Trillions in Assets May Be Left Stranded as Companies Address Climate Change". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Bos, Kyra; Gupta, Joyeeta (1 October 2019). "Stranded assets and stranded resources: Implications for climate change mitigation and global sustainable development". Energy Research & Social Science. 56: 101215. Bibcode:2019ERSS...5601215B. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.025. hdl:11245.1/2da1dc94-53d0-46d2-a6fc-8f0e44c37356. ISSN 2214-6296. S2CID 198658515.

- ^ "No new oil, gas or coal development if world is to reach net zero by 2050, says world energy body". the Guardian. 18 May 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Oil fields map Archived 6 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. quakeinfo.ucsd.edu

- ^ Hsu, Chang Samuel; Robinson, Paul R. (2017). Springer Handbook of Petroleum Technology (2nd, illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 360. ISBN 978-3-319-49347-3. Extract of p. 360

- ^ Caspar Neumann; William Lewis (1759). The Chemical Works of Caspar Neumann ... (1773 printing). J. and F. Rivington. pp. 492–.

- ^ "fossil". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) – "fossil [...] adj. [...] Obtained by digging; found buried in the earth. Now chiefly of fuels and other materials occurring naturally in underground deposits; esp. in FOSSIL FUEL n."

- ^ "fossil". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) – "fossil [...] n. [...] Something preserved in the ground, esp. in petrified form in rock, and recognizable as the remains of a living organism of a former geological period, or as preserving an impression or trace of such an organism."

- ^ "thermochemistry of fossil fuel formation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2015.

- ^ Miller, G.; Spoolman, Scott (2007). Environmental Science: Problems, Connections and Solutions. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-38337-6. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ahuja, Satinder (2015). Food, Energy, and Water: The Chemistry Connection. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-800374-9. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "World Energy Investment 2023" (PDF). IEA.org. International Energy Agency. May 2023. p. 61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b Bousso, Ron (8 February 2023). "Big Oil doubles profits in blockbuster 2022". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. ● Details for 2020 from the more detailed diagram in King, Ben (12 February 2023). "Why are BP, Shell, and other oil giants making so much money right now?". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica, use of oil seeps in ancient times". Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ Bilkadi, Zayn (1992). "Bulls From the Sea: Ancient Oil Industries". Aramco World. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

- ^ Ball, Max W.; Douglas Ball; Daniel S. Turner (1965). This Fascinating Oil Business. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 978-0-672-50829-5.

- ^ Kaldany, Rashad (13 December 2006). Global Gas Flaring Reduction: A Time for Action! (PDF). Global Forum on Flaring & Gas Utilization. Paris: World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ "Oil Sands Global Market Potential 2007". PRLog. 10 August 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (12 December 2017). "Insurance giant Axa dumps investments in tar sands pipelines". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ Eating Fossil Fuels. EnergyBulletin. Archived June 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Soaring fertilizer prices put global food security at risk". Axios. 6 May 2022.

- ^ Erisman, Jan Willem; MA Sutton, J Galloway, Z Klimont, W Winiwarter (October 2008). "How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world". Nature Geoscience. 1 (10): 636–639. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..636E. doi:10.1038/ngeo325. S2CID 94880859. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Butler, Sarah; Ambrose, Jillian (20 October 2021). "Fears global energy crisis could lead to famine in vulnerable countries". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Oswald Spengler (1932). Man and Technics (PDF). Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-8371-8875-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Griffin, Rodman (10 July 1992). "Alternative Energy". CQ Researcher. 2 (2): 573–596.

- ^ a b Michael Stephenson (2018). Energy and Climate Change: An Introduction to Geological Controls, Interventions and Mitigations. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0128120217.

- ^ Neukom, Raphael; Barboza, Luis A.; Erb, Michael P.; Shi, Feng; et al. (2019). "Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era". Nature Geoscience. 12 (8): 643–649. Bibcode:2019NatGe..12..643P. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0400-0. ISSN 1752-0908. PMC 6675609. PMID 31372180.

- ^ "Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change". NASA. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ EPA (19 January 2017). "Climate Impacts on Ecosystems". Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ "WHO calls for urgent action to protect health from climate change – Sign the call". World Health Organization. November 2015. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ WMO Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2019. WMO-No. 1248. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. 2020. ISBN 978-92-63-11248-4. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Gabbard, Alex. "Coal Combustion: Nuclear Resource or Danger". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007.

- ^ Aubrecht II, Gordon J. (2003). "Nuclear proliferation through coal burning" (PDF). Physics Education Research Group, Department of Physics, Ohio State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- ^ American Coal Ash Association. "CCP Production and Use Survey" (PDF).[permanent dead link] [dead link]

- ^ "Annual CO2 emissions by world region" (chart). ourworldindata.org. Our World in Data. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ Damian Carrington (2 December 2020). "World is 'doubling down' on fossil fuels despite climate crisis – UN report". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (2 December 2020). "Humanity is waging war on nature, says UN secretary general". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ "The Production Gap: The discrepancy between countries' planned fossil fuel production and global production levels consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C". UNEP. December 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Leber, Rebecca (12 August 2022). "Fight climate change. End fossilflation. Here's how". Vox. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Horowitz, Julia (13 December 2022). "Analysis: Inflation is finally falling. But the days when prices rose just 2% may never return | CNN Business". CNN. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ a b Wagner, Gernot (23 February 2024). "The Ukraine War Blew Up the World's Energy Economy". heatmap.news. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

Throughout the most recent U.S. spike in inflation in 2022, the energy category alone was responsible for around half of total inflation. And that's just counting the direct effects. Indirectly, a good portion of the food price increases ever since are also due to higher energy costs. If the farmer pays more to harvest the crop, soon those commodity prices increase as well. Of course, it isn't all fossil fuels...The IRA has not and will not cut inflation overnight. But that fight is indeed a big part of the bill's legacy: Play the long game of tackling all three types of climate-related inflation — fossilflation, climateflation, and greenflation — at their very core, and indeed justify the law's name.

- ^ Koester, Gerrit; Lis, Eliza; Nickel, Christiane (2022). "Inflation Developments in the Euro Area Since the Onset of the Pandemic". Intereconomics. 2022 (2): 69–75.

- ^ Van Doorslaer, Hielke; Vermeiren, Mattias (3 September 2021). "Pushing on a String: Monetary Policy, Growth Models and the Persistence of Low Inflation in Advanced Capitalism". New Political Economy. 26 (5): 797–816. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1858774. ISSN 1356-3467. S2CID 230588698.

- ^ Wagner, Gernot (12 August 2022). "Opinion | Greening Your Home Will Be Cheaper, but Expect Growing Pains". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2021). "What are the safest and cleanest sources of energy?". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Data sources: Markandya & Wilkinson (2007); UNSCEAR (2008; 2018); Sovacool et al. (2016); IPCC AR5 (2014); Pehl et al. (2017); Ember Energy (2021).

- ^ Liodakis, E; Dashdorj, Dugersuren; Mitchell, Gary E. (2011). The nuclear alternative: Energy Production within Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 1342. p. 91. Bibcode:2011AIPC.1342...91L. doi:10.1063/1.3583174.

- ^ February 19; Chaisson, 2021 Clara (19 February 2021). "Fossil Fuel Air Pollution Kills One in Five People". NRDC. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Vohra, Karn; Vodonos, Alina; Schwartz, Joel; Marais, Eloise A.; Sulprizio, Melissa P.; Mickley, Loretta J. (April 2021). "Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem". Environmental Research. 195: 110754. Bibcode:2021ER....19510754V. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.110754. PMID 33577774. S2CID 231909881.

- ^ Lelieveld, Jos; Haines, Andy; Burnett, Richard; Tonne, Cathryn; Klingmueller, Klaus; Munzel, Thomas; Pozzer, Andrea (29 November 2023). "Air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels: observational and modelling study". The BMJ. 383: e077784. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-077784. PMC 10686100. PMID 38030155.

- ^ "What are the safest and cleanest sources of energy?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Jogalekar, Ashutosh. "Nuclear power may have saved 1.8 million lives otherwise lost to fossil fuels, may save up to 7 million more". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Energy Transition Investment Now On Par with Fossil Fuel". Bloomberg NEF (New Energy Finance). 10 February 2023. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023.

- ^ "Climate Frontlines Briefing – No Jobs on a Dead Planet" (PDF). International Trade Union Confederation. March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Just Transition Platform". European Commission – European Commission. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Divestment Commitments". Gofossilfree.org. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Gulliver, Robyn (10 October 2022). "Australian Campaign Case Study : Divestment Campaign 2013 - 2021". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Gibson, Dylan; Duram, Leslie (2020). "Shifting Discourse on Climate and Sustainability: Key Characteristics of the Higher Education Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement". Sustainability. 12 (23): 10069. Bibcode:2020Sust...1210069G. doi:10.3390/su122310069.

- ^ "Divestment from Fossil Fuels". Unity College. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Fossil fuel divestment: a brief history". The Guardian. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "The database of fossil fuel divestment commitments made by institutions worldwide". Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Database managed by Stand.earth. 26 July 2023.

- ^ Egli, Florian; Schärer, David; Steffen, Bjarne (1 January 2022). "Determinants of fossil fuel divestment in European pension funds". Ecological Economics. 191: 107237. Bibcode:2022EcoEc.19107237E. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107237. hdl:20.500.11850/517323. ISSN 0921-8009.

- ^ Chung, Connor; Cohn, Dan. "Passive investing in a warming world". Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Trinks, Arjan; Scholtens, Bert; Mulder, Machiel; Dam, Lammertjan (1 April 2018). "Fossil Fuel Divestment and Portfolio Performance". Ecological Economics. 146: 740–748. Bibcode:2018EcoEc.146..740T. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.11.036. hdl:10023/16794. ISSN 0921-8009.

- ^ Kerr, Simeon; Massoudi, Arash; Raval, Anjli (19 December 2019). "Saudi Aramco touches $2tn valuation on second day of trading". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Raval, Anjli; Kerr, Simeon; Stafford, Philip (5 December 2019). "Saudi Aramco raises $25.6bn in world's biggest IPO". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ a b Ritchie, Hannah (27 January 2025). "How much subsidies do fossil fuels receive?". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Local Environmental Externalities due to Energy Price Subsidies: A Focus on Air Pollution and Health" (PDF). World Bank.

- ^ "Fossil fuel subsidies: If we want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions we should not pay people to burn fossil-fuels". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Protecting Nature by Reforming Environmentally Harmful Subsidies: The Role of Business | Earth Track". www.earthtrack.net. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Fossil Fuels Consumption Subsidies 2022 – Analysis". IEA. 16 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "Update on recent progress in reform of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption" (PDF). 2021.

- ^ George, Johannes Urpelainen and Elisha (14 July 2021). "Reforming global fossil fuel subsidies: How the United States can restart international cooperation". Brookings. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Martinez-Alvarez, Cesar B.; Hazlett, Chad; Mahdavi, Paasha; Ross, Michael L. (22 November 2022). "Political leadership has limited impact on fossil fuel taxes and subsidies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (47): e2208024119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11908024M. doi:10.1073/pnas.2208024119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9704748. PMID 36375060.

- ^ Brower, Derek; Wilson, Tom; Giles, Chris (25 February 2022). "The new energy shock: Putin, Ukraine and the global economy". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Why fossil fuel lobbyists are dominating climate policy during Covid-19". Greenhouse PR. 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche (5 November 2021). "Lobbying threat to global climate action". DW.COM. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Laville, Sandra (22 March 2019). "Top oil firms spending millions lobbying to block climate change policies, says report". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ The Guardian, 19 July 2021 "How a Powerful U.S. Lobby Group Helps Big Oil to Block Climate Action" Archived 6 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yale Environment 360, 19 July 2019 "Fossil Fuel Interests Have Outspent Environmental Advocates 10:1 on Climate Lobbying" Archived 6 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Reuters Events, 23 November 2015 "Lobbying: Climate Change—Beware Hot Air" Archived 6 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gaslighting: How APPEA and its members continue to oppose genuine climate action". ACCR. 14 June 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b "IPCC: We can tackle climate change if big oil gets out of the way". The Guardian. 5 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "'Pushes us closer to the abyss': Former Azerbaijani oil executive to head COP29". France 24. 7 January 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ a b Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche (16 April 2020). "Oil and gas companies exploit coronavirus to roll back environmental regulations". DW.COM. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b "US fossil fuel industry leaps on Russia's invasion of Ukraine to argue for more drilling". The Guardian. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad (24 March 2022). "Opinion. We're in a Fossil Fuel War. Biden Should Say So". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Hodgson, Camilla (17 February 2022). "Fossil fuel and agriculture handouts climb to $1.8tn a year, study says". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

Further reading

- Barrett, Ross; Worden, Daniel (eds.), Oil Culture. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

- Bob Johnson, Carbon Nation: Fossil Fuels in the Making of American Culture. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2014.

External links

- Global Fossil Infrastructure Tracker Archived 10 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air