Odonata

| Odonata Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Aeshna juncea hovering over a pond. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| (unranked): | Dicondylia |

| Subclass: | Pterygota |

| Division: | Palaeoptera |

| Superorder: | Odonatoptera |

| Order: | Odonata Fabricius, 1793 |

| Suborders | |

For extinct groups, see text | |

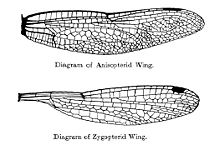

Odonata is an order of predatory flying insects that includes the dragonflies and damselflies (as well as the Epiophlebia damsel-dragonflies). The two major groups are distinguished with dragonflies (Anisoptera) usually being bulkier with large compound eyes together and wings spread up or out at rest, while damselflies (suborder Zygoptera) are usually more slender with eyes placed apart and wings folded together along body at rest. Adult odonates can land and perch, but rarely walk.

All odonates have aquatic larvae called naiads or nymphs, and all of them, larvae and adults, are carnivorous and are almost entirely insectivorous, although at the larval stage they will eat anything that they can overpower, including small fish, tadpoles, and even adult newts. The adults are superb aerial hunters and their legs are specialised for catching prey in flight.

Odonata in its narrow sense forms a subgroup of the broader Odonatoptera, which contains other dragonfly-like insects.

Etymology and terminology

[edit]Johan Christian Fabricius coined the term Odonata in 1793 from the Ancient Greek ὀδών odṓn (Ionic form of ὀδούς odoús) "tooth". One hypothesis is that it was because their maxillae are notably toothed.[1]

The word dragonfly usually denotes only Anisoptera, but is sometimes used to mean all Odonata.[2] Odonata enthusiasts avoid ambiguity by using the term true dragonfly,[3] or simply anisopteran,[4] when they mean just the Anisoptera. An alternative term warriorfly has been proposed.[5]

External morphology

[edit]Size

[edit]The largest living odonate is the giant Central American helicopter damselfly Megaloprepus coerulatus (Zygoptera: Pseudostigmatidae) with a wing span of 191 mm (7.5 in). The heaviest living odonates are Tetracanthagyna plagiata (Anisoptera: Aeshnidae) with a wing span of 165 mm (6.5 in), and Petalura ingentissima (Anisoptera: Petaluridae) with a body length of 117 mm (4.6 in) (some sources 125 mm (4.9 in)) and wing span of 160 mm (6.3 in). The longest extant odonate is the Neotropical helicopter damselfly Mecistogaster linearis (Zygoptera: Pseudostigmatidae) with a body length of 135 mm (5.3 in).[6]

The smallest living dragonfly is Nannophya pygmaea (Anisoptera: Libellulidae) from east Asia, with a body length of 15 mm (0.59 in) and a wing span of 20 mm (0.79 in). The smallest damselflies (and also the smallest odonates) are species of the genus Agriocnemis (Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae) with a wing span of only 17–18 mm (0.67–0.71 in).[7]

Description

[edit]

These insects characteristically have large rounded heads covered mostly by well-developed, compound eyes, which provide good vision, legs that facilitate catching prey (other insects) in flight, two pairs of long, transparent wings that move independently, and elongated abdomens. They have three ocelli and short antennae. The mouthparts are on the underside of the head and include simple chewing mandibles in the adult.[8]

Flight in the Odonata is direct, with flight muscles attaching directly to the wings; rather than indirect, with flight muscles attaching to the thorax, as is found in the Neoptera. This allows active control of the amplitude, frequency, angle of attack, camber and twist of each of the four wings entirely independently.[9]

In most families, there is a structure on the leading edge near the tip of the wing called the pterostigma. This is a thickened, hemolymph–filled and often colorful area bounded by veins. The functions of the pterostigma are not fully known, but it most probably has an aerodynamic effect and may also have a visual function. More mass at the end of the wing may also reduce the energy needed to move the wings up and down. The right combination of wing stiffness and wing mass could reduce the energy consumption of flying. A pterostigma is also found among other insects, such as bees.[10]

The nymphs have stockier, shorter, bodies than the adults. In addition to lacking wings, their eyes are smaller, their antennae longer, and their heads are less mobile than in the adult. Their mouthparts are modified, with the labium being adapted into a unique prehensile organ called a labial mask for grasping prey.[11] Damselfly nymphs breathe through external gills on the abdomen, while dragonfly nymphs respire through an organ in their rectum.[8]

Evolution

[edit]Fossil history

[edit]

Members of the crown group Odonata first appeared during the Late Triassic,[13] though members of their total group, Odonatoptera, first appeared in the Late Carboniferous, making them one of the earliest groups of winged insects.[13] The fossils of odonates and their cousins, including Paleozoic "giant dragonflies" like Meganeuropsis permiana from the Permian of North America, reached wing spans of up to 71 cm (28 in) and a body length of 43 cm (17 in), making it the largest insect of all time.[14] This insect belonged to the order Meganisoptera, the griffinflies, related to odonates but not part of the modern order Odonata in the restricted sense. They have one of the most complete fossil records going back 319 million years.[15]

The Odonata is closely related to mayflies and several extinct orders in a group called the Palaeoptera, but this grouping might be paraphyletic. What they do share with mayflies is the nature of how the wings are articulated and held in rest.[16]

Tarsophlebiidae is a prehistoric family of Odonatoptera that can be considered either a basal lineage of Odonata or their immediate sister taxon.[17]

Phylogeny

[edit]The phylogenetic tree of the orders and suborders of odonates according to Bybee et al. 2021:[18]

| Odonata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomy

[edit]In some treatments,[19] the Odonata are understood in an expanded sense, essentially synonymous with the superorder Odonatoptera, but not including the prehistoric Protodonata. In this approach, instead of Odonatoptera, the term Odonatoidea is used. The systematics of the "Palaeoptera" are by no means resolved; what can be said however is that regardless of whether they are called "Odonatoidea" or "Odonatoptera", the Odonata and their extinct relatives do form a clade.[20]

The Anisoptera was long treated as a suborder, with a third suborder, the Anisozygoptera (ancient dragonflies). However, the combined suborder Epiprocta (in which Anisoptera is an infraorder) was proposed when it was thought that the "Anisozygoptera" was paraphyletic, composed of mostly extinct offshoots of dragonfly evolution. The four living species placed in that group are (in this treatment) in the infraorder Epiophlebioptera, whereas the fossil taxa that were formerly there are now dispersed about the Odonatoptera (or Odonata sensu lato).[21][22] World Odonata List considers Anisoptera as a suborder along with Zygoptera and Anisozygoptera as well-understood and widely preferred terms.[23][24]

Cladogram of Epiprocta after Rehn et al. 2003[25]:

| Odonata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram of Odonatoptera including Odonata by Deregnaucourt et al. 2023.[26]

| Odonatoptera (Odonata sensu lato) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ecology and life cycle

[edit]

Odonates are aquatic or semi-aquatic as juveniles. Thus, adults are most often seen near bodies of water and are frequently described as aquatic insects. However, many species range far from water. They are carnivorous (or more specifically insectivorous) throughout their life, mostly feeding on smaller insects.[27]

Male Odonata have complex genitalia, different from those found in other insects. These include grasping cerci at the tip of the abdomen for holding the female, and a secondary set of copulatory organs located between the second and third abdominal segment in which the spermatozoa are stored after being produced by the primary genitals— whose external opening is known as the genital pore, on the ninth abdominal segment. This process is called intra-male sperm translocation (ST).[28][29] Because the male copulatory organ has evolved independently from that in other insects, it has been suggested the stem-group dragonflies had external sperm transfer.[30] To mate, the male claspers grasps the female by the thorax (Zygoptera) or head (Anisoptera) while the female bends her abdomen so that her own genitalia can be grasped by the copulatory organ holding the sperm. This is known as the "wheel" position.[8] In Anisoptera, males often mate while flying, lifting the females in the air, which typically last from a couple of seconds to a minute or two, whereas the males in Zygoptera mate while perched. They might even move to different spots during the mating process, which can make it last longer, anywhere between five to ten minutes. Male Odonata are very competitive when it comes to mating that in some species, the males use the cerci located at the tip of the abdomen to remove the sperm of a rival male's from the female and put in his own.[31][32]

Eggs are laid in water or on vegetation near water or wet places, and hatch to produce pronymphs which live off the nutrients that were in the egg. They then develop into instars with approximately 9–14 molts that are (in most species) voracious predators on other aquatic organisms, including small fishes. The nymphs grow and molt, usually in dusk or dawn, into the flying teneral immature adults, whose color is not yet developed. These transform into reproductive adults.[citation needed]

Odonates can act as bioindicators of water quality in rivers because they rely on high quality water for proper development in early life. Since their diet consists entirely of insects, odonate density is directly proportional to the population of prey, and their abundance indicates the abundance of prey in the examined ecosystem.[33] Species richness of vascular plants has also been positively correlated with the species richness of dragonflies in a given habitat. This means that in a location such as a lake, if one finds a wide variety of odonates, then a similarly wide variety of plants should also be present. This correlation is not common to all bioindicators, as some may act as indicators for a different environmental factor, such as the pool frog acting as a bioindicator of water quality due to its high quantity of time spent in and around water.[34]

In addition, odonates are very sensitive to changes to average temperature. Many species have moved to higher elevations and latitudes as global temperature rises and habitats dry out. Changes to the life cycle have been recorded with increased development of the instar stages and smaller adult body size as the average temperature increases. As the territory of many species starts to overlap, the rate hybridization of species that normally do not come in contact is increasing. If global climate change continues many members of Odonata will start to disappear. Because odonates are such an old order and have such a complete fossil record they are an ideal species to study insect evolution and adaptation. For example, they are one of the first insects to develop flight and it is likely that this trait only evolved once in insects, looking at how flight works in odonates, the rest of flight can be mapped out.[15]

Gallery

[edit]-

A pair of Ceriagrion cerinorubellum mating

-

Libellula depressa resting

-

Nymph

-

Anax imperator in flight

See also

[edit]Various lists of Odonata species of different regions:

References

[edit]- ^ Mickel, Clarence E. (1934). "The significance of the dragonfly name "Odonata"". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 27 (3): 411–414. doi:10.1093/aesa/27.3.411.

- ^ "odonate". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Field Guide to Lower Aquarium Animals. Cranbrook Institute of Science. 1939.

- ^ Orr, A.G. (2005). Dragonflies of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Borneo: Natural History Publications. ISBN 978-983-812-103-3.

- ^ Corbet, Philip S.; Brook, Stephen J. (2008). Dragonflies. London, UK: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-715169-1.

- ^ Wilson, Keith D. P. (2009-01-01). "Dragonfly Giants". Agrion. 13 (1): 29–31. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ Kipping, Jens; Martens, Andreas; Suhling, Frank (2012). "Africa's smallest damselfly—a new Agriocnemis from Namibia (Odonata: Coenagrionidae)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 12 (3): 301–306. Bibcode:2012ODivE..12..301K. doi:10.1007/s13127-012-0084-4. ISSN 1439-6092.

- ^ a b c Hoell, H.V., Doyen, J.T. & Purcell, A.H. (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 355–358. ISBN 978-0-19-510033-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bomphrey, Richard J.; Nakata, Toshiyuki; Henningsson, Per; Lin, Huai-Ti (2016). "Flight of the dragonflies and damselflies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371 (1704): 2015.0389. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0389. PMC 4992713. PMID 27528779.

- ^ Norberg, R. Åke (1972). "The pterostigma of insect wings an inertial regulator of wing pitch". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 81 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1007/BF00693547. S2CID 23441098.

- ^ Büsse, S.; Tröger, H.-L.; Gorb, S.N. (11 August 2021). "The toolkit of a hunter – functional morphology of larval mouthparts in a dragonfly". Journal of Zoology. 315 (4): 247–260. doi:10.1111/jzo.12923.

- ^ The Biology of Dragonflies. Cambridge University Press Archive. 2018. p. 324. GGKEY:0Z7A1R071DD.

No Dragonfly at present existing can compare with the immense Meganeura monyi of the Upper Carboniferous, whose expanse of wing was somewhere about twenty-seven inches.

- ^ a b Kohli, Manpreet Kaur; Ware, Jessica L.; Bechly, Günter (2016). "How to date a dragonfly: Fossil calibrations for odonates". Palaeontologia Electronica. 19 (1): 576. doi:10.26879/576.

- ^ Mitchell, F.L.; Lasswell, J. (2005). A Dazzle of Dragonflies. Texas A&M University Press. p. 47.

- ^ a b Bybee, Seth; Córdoba-Aguilar, Alex; Duryea, M. Catherine; et al. (December 2016). "Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) as a bridge between ecology and evolutionary genomics". Frontiers in Zoology. 13 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/s12983-016-0176-7. ISSN 1742-9994. PMC 5057408. PMID 27766110.

- ^ Ninomiya, Tomoya; Yoshizawa, Kazunori (2009). "A revised interpretation of the wing base structure in Odonata". Systematic Entomology. 34 (2): 334–345. Bibcode:2009SysEn..34..334N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2008.00455.x. hdl:2115/42988. ISSN 0307-6970.

- ^ Fleck, G.; Bechly, G.; Martinez-Delclòs, X.; Jarzembowski, E.A.; Nel, A. (2004-06-01). "A revision of the Mesozoic dragonfly family Tarsophlebiidae, with a discussion on the phylogenetic positions of the Tarsophlebiidae and Sieblosiidae (Odonatoptera: Panodonata)". Geodiversitas. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ Bybee, Seth M.; Kalkman, Vincent J.; Erickson, Robert J.; et al. (2021). "Phylogeny and classification of Odonata using targeted genomics". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 160. Elsevier BV: 107115. Bibcode:2021MolPE.16007115B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107115. hdl:11093/2768. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 33609713.

- ^ Trueman & Rowe (2008).

- ^ Trueman (2008).

- ^ Lohmann (1996).

- ^ Rehn (2003).

- ^ Paulson, D.; Schorr, M.; Abbott, J.; Bota-Sierra, C.; Deliry, C.; Dijkstra, K.-D.; Lozano, F. (2024). "World Odonata List". OdonataCentral, University of Alabama.

- ^ Bybee, Seth M.; Kalkman, Vincent J.; Erickson, Robert J.; Frandsen, Paul B.; Breinholt, Jesse W.; Suvorov, Anton; et al. (2021a). "Phylogeny and classification of Odonata using targeted genomics". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 160: 107115. Bibcode:2021MolPE.16007115B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107115. hdl:11093/2768. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 33609713.

- ^ Rehn (2003), pp. 181–240.

- ^ Deregnaucourt, Isabelle; Bardin, Jérémie; Villier, Loïc; Julliard, Romain; Béthoux, Olivier (August 2023). "Disparification and extinction trade-offs shaped the evolution of Permian to Jurassic Odonata". iScience. 26 (8): 107420. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.107420. PMC 10424082. PMID 37583549.

- ^ May, ML (28 February 2019). "Odonata: Who They Are and What They Have Done for Us Lately: Classification and Ecosystem Services of Dragonflies". Insects. 10 (3): 62. doi:10.3390/insects10030062. PMC 6468591. PMID 30823469.

- ^ Kirti, Jagbir S.; Singh, Archana (June 2004). "Studies on the secondary male Genitalia of the type species of some dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera: Libellulidae)". Case report. Zoos' Print Journal. 19 (6): 1505–1511. doi:10.11609/JoTT.ZPJ.984.1505-11. Archived from the original on 2024-02-28. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ Evolution and diversity of intra-male sperm translocation in Odonata: A unique behaviour in animals. agris.fao.org (Report). U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. United Nations. 2019.

- ^ Beutel, Rolf G.; Yavorskaya, Margarita I.; Mashimo, Yuta; Fukui, Makiko; Meusemann, Karen (2017). "The phylogeny of Hexapoda (Arthropoda) and the evolution of megadiversity" (PDF). Proceedings of the Arthropod and Embryological Society of Japan. 51: 1–15. ISSN 1341-1527.

- ^ "Mating and Reproduction in Odonata". www.brisbaneinsects.com. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- ^ "Odonata: Dragonflies and Damselflies". ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- ^ Golfieri, Bruno; Hardersen, Sönke; Maiolini, Bruno; Surian, Nicola (2016). "Odonates as indicators of the ecological integrity of the river corridor: Development and application of the Odonate River Index (ORI) in northern Italy". Ecological Indicators. 61: 234–247. Bibcode:2016EcInd..61..234G. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.09.022. ISSN 1470-160X.

- ^ Sahlén, Göran; Ekestubbe, Katarina (16 May 2000). "Identification of dragonflies (Odonata) as indicators of general species richness in boreal forest lakes". Biodiversity and Conservation. 10 (5): 673–690. doi:10.1023/A:1016681524097. S2CID 40735036.

Cited sources

[edit]- Lohmann, H. (1996). "Das phylogenetische System der Anisoptera (Odonata)". Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift. 106 (9): 209–266.

- Rehn, A. (2003). "Phylogenetic analysis of higher-level relationships of Odonata". Systematic Entomology. 28 (2): 181–240. Bibcode:2003SysEn..28..181R. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3113.2003.00210.x.

- Trueman, John W. H. (2008). "Pterygote Higher Relationships". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- Trueman, John W. H.; Rowe, Richard J. (20 March 2008). "Odonata. Dragonflies and damselflies". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

External links

[edit]- "Anatomy of Odonata". sunsite.ualberta.ca. Aquatic invertebrates. University of Alberta. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17.

- "Dragonflies and damselflies". Featured Creatures. IFAS. University of Florida.

- "Dragonflies and Damselflies (Odonata) of the United States". npwrc.usgs.gov. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. — U.S. state-by-state listing with distribution maps, images

- "IORI species list, photos, and social media links". iodonata.net. Archived from the original on 2007-05-29.

- "Journal of the Entomological Research Society" (main page).

- "Odonata Central". odonatacentral.org (main page).

- "Odonatologica". odonatologica.com (main page).

- "World Odonata list". pugetsound.edu. University of Puget Sound.