Out-of-place artifact

An out-of-place artifact (OOPArt or oopart) is an artifact of historical, archaeological, or paleontological interest to someone that is claimed to have been found in an unusual context, which someone claims to challenge conventional historical chronology by its presence in that context. Some people might think that those artifacts are too advanced for the technology known to have existed at the time, or that human presence existed at a time before humans are known to have existed. Other people might hypothesize about a contact between different cultures that is hard to account for with conventional historical understanding.

This description of archaeological objects is used in fringe science such as cryptozoology, as well as by proponents of ancient astronaut theories, young Earth creationists, and paranormal enthusiasts.[1][2] It can describe a wide variety of items, from anomalies studied by mainstream science to pseudoarchaeology to objects that have been shown to be hoaxes or to have conventional explanations.

Critics argue that most purported OOPArts which are not hoaxes are the result of mistaken interpretation and wishful thinking, such as a mistaken belief that a particular culture could not have created an artifact or technology due to a lack of knowledge or materials. In some cases, the uncertainty results from inaccurate descriptions. For example, the cuboid Wolfsegg Iron is not really a perfect cube, nor are the Klerksdorp spheres actual perfect spheres. The Iron pillar of Delhi was said to be "rust proof", but it has some rust near its base; its relative resistance to corrosion is due to slag inclusions left over from the manufacturing conditions and environmental factors.[3]

Supporters regard OOPArts as evidence that mainstream science is overlooking huge areas of knowledge, either willfully or through ignorance.[2] Many writers or researchers who question conventional views of human history have used purported OOPArts in attempts to bolster their arguments.[2] Creation science often relies on allegedly anomalous finds in the archaeological record to challenge scientific chronologies and models of human evolution.[4] Claimed OOPArts have been used to support religious descriptions of prehistory, ancient astronaut theories, and the notion of vanished civilizations that possessed knowledge or technology more advanced than that known in modern times.[2]

Unusual artifacts

[edit]- Antikythera mechanism: A form of mechanical computer created between 150 and 100 BCE based on theories of astronomy and mathematics believed to have been developed by the ancient Greeks. Its design and workmanship reflect a previously unknown degree of sophistication and engineering.[5][6]

- Maine penny: An 11th-century Norwegian coin found in a Native American shell midden at the Goddard Site in Brooklin, Maine, United States, which some authors have argued is evidence of direct contact between Vikings and Native Americans in Maine. The coin need not imply actual exploration of Maine by the Vikings, however; mainstream belief is that it was brought to Maine from Labrador or Newfoundland (where Vikings are known to have established colonies as early as the late 10th century) via an extensive northern trade network operated by indigenous peoples.[7] If Vikings did indeed visit Maine, a much greater number and variety of Viking artifacts might be expected in the archaeological record there.[8] Of the nearly 20,000 objects found over a 15-year period at the Goddard Site, the coin was the sole non-native artifact.[citation needed]

- The Tamil Bell is a broken bronze bell with an inscription of old Tamil. The bell is a mystery due to its discovery in New Zealand by a missionary. Although nobody knows for certain how the bell came to New Zealand, one possible theory is that it was dropped off by Portuguese sailors who had acquired it from Tamil traders. Prior to being discovered by the missionary, local Maori had used it as a cooking pot. Given that it was supposedly discovered generations earlier, the artifact's exact origins could not be identified. The bell is now located at the National Museum of New Zealand.[9]

- Coins from Marchinbar Island: Five coins from the Kilwa Sultanate on the Swahili coast discovered on Marchinbar Island in the Northern Territory of Australia in 1945 alongside four coins from 18th century Netherlands. The inscriptions on the coins identify a ruling Sultan of Kilwa, but it is unclear whether the ruler was from the 10th century or the 14th century. A similar coin, also thought to be from the Medieval Kilwa sultanate, was found in Australia in 2018 on Elcho Island.[10]

- Traces of cocaine and nicotine found in Egyptian mummies, which have been variously interpreted as evidence of contact between Ancient Egypt and Pre-Columbian America or as the result of contamination.[11]

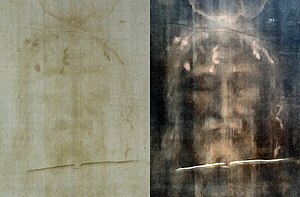

- The Shroud of Turin contains an image that resembles a sepia photographic negative, established by radiocarbon dating to have been produced between the years 1260 and 1390.[12] The technology of photographic negatives was introduced in 1839 by Henry Fox Talbot and the fact that the image on the shroud is much clearer when it is converted to a positive image wasn't discovered until Secondo Pia photographed it in 1898. The actual method that resulted in this image has not yet been conclusively identified; no traces of pigments or dyes have been found, and hypotheses about a medieval proto-photographic process, a rubbing technique, natural chemical processes or some kind of radiation have not convinced many researchers.[13] Mention of the shroud first appeared in historical records in 1357. All hypotheses put forward to challenge the radiocarbon dating have been scientifically refuted,[12] including the medieval repair hypothesis,[14][15][16] the bio-contamination hypothesis[17] and the carbon monoxide hypothesis.[18] It has traditionally been believed that the cloth is the burial shroud in which Jesus of Nazareth was wrapped after crucifixion.

Questionable interpretations

[edit]

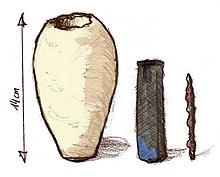

- Baghdad Battery: A ceramic vase, a copper tube, and an iron rod made in Parthian or Sassanid Persia, discovered in 1936. Fringe theorists have hypothesized that it may have been used as a galvanic cell for electroplating, though no electroplated artifacts from this era have been found.[19][20] The "battery" strongly resembles another type of object with a known purpose – storage vessels for sacred scrolls from nearby Seleucia on the Tigris.[21]

- Dorchester Pot: A metal pot claimed to have been blasted out of solid rock in 1852. Mainstream commentators identify it as a Victorian-era candlestick or pipe holder.[22][23]

- Kingoodie artifact: An object resembling a corroded nail, said to have been encased in solid rock. It was handled a number of times before being reported and there are no photographs of it.[24][25]

- Lake Winnipesaukee mystery stone: Originally thought to be a record of a treaty between tribes, subsequent analysis has called its authenticity into question.[26][27]

- Sivatherium of Kish: An ornamental war chariot figurine discovered in the Sumerian ruins of Kish, in what is now central Iraq, in 1928. The figurine, dated to the Early Dynastic I period (2800–2750 BCE), depicts a quadrupedal mammal with branched horns, a nose ring, and a rope tied to the ring. Because of the shape of the horns, Edwin Colbert identified it in 1936 as a depiction of a late-surviving, possibly domesticated Sivatherium, a vaguely moose-like relative of the giraffe that lived in North Africa and India during the Pleistocene but was believed to have become extinct early in the Holocene extinction event.[28] Henry Field and Berthold Laufer instead argued that it represented a captive Persian fallow deer and that the antlers had broken over the years. The missing antlers were indeed found in the Field Museum's storeroom in 1977.[29] After restoration in 1985, it was conclusively identified as a depiction of a Caspian red deer (Cervus elaphus maral).[30]

- Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca head: A terracotta offering head seemingly of Roman appearance found beneath three intact floors of a burial site in Mexico and dated between 1476 and 1510. There are disputed claims that its dating is older. Ancient Roman or Norse provenance has not been excluded.[31][32]

- The Westford Knight: A pattern, variously interpreted as a carving or a natural feature, or a combination of both, located on a glacial boulder in Westford, Massachusetts in the United States. Pseudohistorical interpertations have labeled it as evidence of pre-Columbian contact with Medieval Europe.

Alternative interpretations

[edit]

- Abydos helicopter: A pareidolia based on palimpsest carving in an ancient Egyptian temple.[33]

- Dendera Lamps: Supposed to depict light bulbs, but made in Ptolemaic Egypt, debunked by the analysis of the epigraphic text. The motif actually represents a lotus flower.[34][35][36]

- Sabu disk: a disk of notable precision apparently from ancient times in Saqqara. Its purpose is unknown.[37]

- Iron Man (Eiserner Mann): An old iron pillar, said to be a unique oddity in Germany, but consistent with medieval methods of ironworking.[38]

- Iron pillar of Delhi: A "rust-proof" iron pillar which supposedly demonstrates more advanced metallurgy than was available in India before 1000 CE.[39]

- London Hammer: Also known as the "London Artifact", a hammer made of iron and wood that was found in London, Texas, in 1936. Part of the hammer is encased in "400-million-year-old" ("Ordovician era") rock. In 1985, anthropologist John R. Cole[40] hypothesized that the stone surrounding the hammer is a historic carbonate soil concretion.

- Meister Print: A supposed human footprint from the Cambrian period, long before humans existed, which has been debunked as the result of a natural geologic process known as spall formation.[41]

- Pacal's sarcophagus lid: Described by Erich von Däniken as a depiction of a spaceship's cockpit.[42]

- Piri Reis map: Several authors, and others such as Gavin Menzies and Charles Hapgood, have suggested that this map, compiled by the Turkish admiral Piri Reis, shows Antarctica long before it was discovered (cf. Terra Australis).[43][44]

- Quimbaya airplanes: Golden objects found in Colombia and made by the Quimbaya civilization, which have been alleged to represent modern airplanes. In the Gold Museum, Bogotá, they are described as figures of birds and insects. Some of the artifacts have also been debunked as forgeries.[45]

- Saqqara Bird: Supposedly depicts a glider, but made in Ancient Egypt.[46]

- Shakōkidogū: Small humanoid and animal figurines made during the late Jōmon period (14,000–400 BCE) of prehistoric Japan, said to resemble extraterrestrial astronauts.[47]

- Stone spheres of Costa Rica: Inaccurately described as being perfectly spherical, and therefore demonstrating greater stone-working skill in pre-Columbian times than has previously been known.[48]

- Fuente Magna, a large stone vessel that was discovered in Bolivia in 1950, with many engravings on its inside that have been compared to Sumerian cuneiform writing. Archeologist and historian of the Near East Alexander H. Joffe has described the patterns as "geometric filler or deliberate gibberish" and thought the face on the interior resembles local Tiwanaku culture. He suggested it could be a fake or a local oddity.[49]

Natural objects mistaken for artifacts

[edit]

- Aix-en-Provence petrified tools: Likely petrified tree remains.[50][51]

- Baigong pipes: Their natural origins have been challenged.[52][53][54]

- Bosnian pyramid complex: Unproven claim that there is a pyramid complex in the vicinity of town of Visoko in Bosnia, made by ancient Bosnians.

- Eltanin Antenna: Actually a sponge.[55][56]

- Eoliths: Miocene knapped flint nodules mistaken in the 19th century for extremely primitive stone tools, which helped back the authenticity of Piltdown Man.

- Face on Mars: A pareidolia of a rock formation on Mars caused by the poor resolution of early orbital photography of the planet.[57]

- Klerksdorp spheres: Actually pre-Cambrian concretions.[58][59]

- Gunung Padang pyramid: megalithic site built on the slopes of an ancient volcano which has been misidentified as a 20,000 year old pyramid.[60]

- Paluxy River tracks: Identified as giant humanoid footprints found alongside dinosaur tracks. Actually tracks of theropod dinosaurs, and 1930s forgeries.

- Yonaguni Monument: An unusual underwater rock formation near the southern Ryukyu Islands. Was considered a man-made monolith because of the even cracks.[61][62]

- Ararat anomaly: The Ararat anomaly is a structure appearing on photographs of the snowfields near the summit of Mount Ararat, Turkey, initially believed by some Christian believers to be the remains of Noah's Ark. Located on the northwest corner of the Western Plateau of Mount Ararat, approximately 15,500 ft high, it was first filmed during a U.S. Air Force aerial reconnaissance mission in 1949. The Defense Intelligence Agency later indicated that the anomaly represents linear facades in the glacial ice, rather than an ancient structure.[63][64]

Erroneously dated objects

[edit]- Aiud object: An aluminum wedge found in 1974 in the Mureș River in central Romania, near the town of Aiud; it has been claimed by Romanian ufologists to be of ancient and/or extraterrestrial origin,[65] yet it is more likely a fragment of modern machinery lost during excavation work.[66]

- Coso artifact: Claimed to be prehistoric; actually a 1920s spark plug.[4]

- Malachite Man: Thought to be from the early Cretaceous; actually a post-Columbian burial.[67][68]

- Nampa figurine: Was a clay fired doll found in Nampa, Idaho during a well drilling. Early dating attempts believed the artifact to be 2 million years old due to the rock layer it was found in.[69] Later assessments found that the artifact was either only a few thousand years old[70] or a 19th-century Native American doll. Many have criticized the object as a likely hoax.[71]

- Wolfsegg Iron: Thought to be from the Tertiary epoch; actually from an early mining operation. Inaccurately described as a perfect cube.[72]

Modern-day creations, forgeries and hoaxes

[edit]

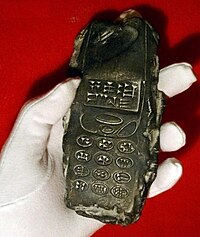

- Babylonokia: A clay tablet shaped like a mobile phone and created as an artwork in 2012. Fringe scientists and alternative archaeology proponents subsequently misrepresented a photograph of the artwork as showing an 800-year-old archaeological find. The story was popularised in a video on the YouTube channel Paranormal Crucible and led to the object being reported by some press sources as a mystery.[73]

- Acámbaro figures: Mid-20th-century figurines of dinosaurs, attributed by Waldemar Julsrud to an ancient society.[74]

- Calaveras Skull: A human skull found by miners in Calaveras County, California, which was purported to prove that humans, mastodons, and elephants had coexisted in prehistoric California. It was later revealed to be a hoax.[75]

- Cardiff Giant: A 19th-century hoax of a ten-foot-tall supposedly petrified man exhibited as a giant from biblical times. Quickly debunked by experts, and by the confession of the forger,[76] it was nonetheless a popular marvel of the day.[77]

- Crystal skulls: Supposedly demonstrate more advanced stone-cutting skill than was previously known from pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Appear to have been made in the 19th century.[78]

- Gosford Glyphs: A collection of Egyptian hieroglyphs on the Central Coast, Australia, that have been dismissed as a hoax by authorities and academics after their discovery in the 1970s.[79]

- Ica stones: Depict Inca dinosaur-hunters, surgery, and other modern or fanciful topics. Collected by Javier Cabrera Darquea, who claimed them to be prehistoric. Later revealed to be a forgery created by a local farmer.[80]

- Japanese Paleolithic hoax: Perpetrated by discredited amateur archaeologist Shinichi Fujimura.[81]

- Kensington Runestone: A runestone purportedly unearthed in 1898 in Kensington, Minnesota entangled in the roots of a tree. Runologists have dismissed the inscription's authenticity on linguistic evidence, while geologists disagree as to whether the stone shows weathering that would indicate a medieval date.[82]

- Los Lunas Decalogue Stone: Supposedly made by pre-Columbian Israelite visitors to the Americas. Generally believed to be a modern-day hoax.[83]

- Michigan relics: Supposedly ancient artifacts which have been alleged as proof that people of an ancient Near Eastern culture had lived in the U.S. state of Michigan; they are archaeological forgeries.[84]

- Newark Holy Stones: Hoax "artifacts" used as extremely unlikely evidence that Hebrew peoples lived in the Precolumbian Americas.[85]

- Piltdown Man: Supposedly skull parts from a "missing link" hominid, but exposed as an elaborate hoax 41 years after its "discovery".[86]

- Tucson artifacts: Thirty-one lead objects that Charles E. Manier and his family found in 1924 near Picture Rocks, Arizona, which were initially thought by some to be created by early Mediterranean civilizations that had crossed the Atlantic in the first century, but were later determined to be a hoax.[87]

See also

[edit]- Acheiropoieta

- Anachronism

- Ancient technology

- Geofact

- Lazarus taxon

- Lost inventions

- Pseudohistory

- Silurian hypothesis

Authors and works

[edit]- Charles Fort, researcher of anomalous phenomena

- Chariots of the Gods?, 1968 book by Erich Von Daniken

- Fortean Times

- Peter Kolosimo

- Fingerprints of the Gods, 1995 book by Graham Hancock

- Vadim Chernobrov, researcher of anomalous phenomena, writer

- Michael Cremo, author of several books including Forbidden Archeology (1993)

- Charles Berlitz, linguist and writer of anomalous phenomena

- The Mysterious Origins of Man, originally aired on NBC in 1996

References

[edit]- ^ Benjamin B. Olshin (2019). Lost Knowledge: The Concept of Vanished Technologies and Other Human Histories. Brill. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-90-04-35272-8.

- ^ a b c d O'Hehir, Andrew (August 31, 2005). "Archaeology from the dark side". Salon.com. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ R. Balasubramaniam (2001). "New Insights on the Corrosion Resistant Delhi Iron Pillar". In Rao, Ramachandra Patcha; Goswami, Nani Gopal (eds.). Metallurgy in India: a retrospective (PDF). India International Publisher. pp. 104–133.

- ^ a b Stromberg, P, and PV Heinrich (2004) The Coso Artifact Mystery from the Depths of Time? Archived 2007-12-14 at the Wayback Machine, Reports of the National Center for Science Education. 24(2):26–30 (March/April 2004) Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project Archived 2008-04-28 at the Wayback Machine", The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project. Retrieved 2007-07-01 Quote: "The Antikythera Mechanism is now understood to be dedicated to astronomical phenomena and operates as a complex mechanical "computer" which tracks the cycles of the Solar System."

- ^ Paphitis, Nicholas (December 1, 2006). "Experts: Fragments an Ancient Computer". The Washington Post. Athens, Greece.

Imagine tossing a top-notch laptop into the sea, leaving scientists from a foreign culture to scratch their heads over its corroded remains centuries later. A Roman shipmaster inadvertently did something just like it 2,000 years ago off southern Greece, experts said late Thursday.

- ^ "Vinland Archeology". Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 2003-12-09. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ "Bye, Columbus". Time. December 11, 1978. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007.

- ^ J., Wilkie & Co. (1918). "New Zealand Journal of Science". Technology. 1. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Stevenson, Kylie (11 May 2019). "'It could change everything': coin found off northern Australia may be from pre-1400 Africa". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ S. A. Wells. "American Drugs in Egyptian Mummies". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b Taylor, R.E.; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2014). Radiocarbon Dating: An Archaeological Perspective (2nd ed.). Left Coast Press. pp. 165–168. ISBN 978-1-59874-590-0.

- ^ "How did the Turin Shroud get its image?". BBC News. 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ Freer-Waters, Rachel A.; Jull, A. J. Timothy (2010). "Investigating a Dated Piece of the Shroud of Turin". Radiocarbon. 52 (4): 1521–1527. doi:10.1017/S0033822200056277. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ Schafersman, Steven D. (14 March 2005). "A Skeptical Response to Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin by Raymond N. Rogers". llanoestacado.org. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Ian (2010). The Shroud. London: Bantam Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-593-06359-0.

- ^ Gove, H. E. (1990). "Dating the Turin Shroud: An Assessment". Radiocarbon. 32 (1): 87–92. doi:10.1017/S0033822200039990.

- ^ Ramsey, Christopher (March 2008). "The Shroud of Turin". Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ Plating and Surface Finishing. vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 84–87. Von Handorf, D.E. (May 2002). "The Baghdad Battery—Myth or Reality?" (PDF). Platin & Surface Finishing. 89 (5): 84–87.

- ^ Flatow, I (2012) Archaeologists Revisit Iraq. interview with Elizabeth Stone, Talk of the Nation, National Public Radio. Washington, DC.

- ^ Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews (26 December 2009). "The batteries of Babylon: evidence for ancient electricity?". Bad Archaeology. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Steiger, B. (1979) Worlds Before Our Own. New York, New York, Berkley Publishing Group. 236 pp. ISBN 978-1-933665-19-1

- ^ Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K, and J Doeser (2007) Metallic vase from Dorchester, Massachusetts. Bad Archaeology.

- ^ Sir David, B (1854) Queries and Statements concerning a Nail found imbedded in a Block of Sandstone obtained from Kingoodie (Mylnfield) Quarry, North Britain. Report of the Fourteenth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science vol. 51, John Murray London.

- ^ Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K, and J Doeser (2007) A nail in Devonian sandstone from Kingoodie, Scotland. Bad Archaeology.

- ^ anonymous (nd) The Mystery Stone. Archived 2010-09-14 at the Wayback Machine Museum Exhibits, New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, New Hampshire.

- ^ Klatell, JM (July 23, 2006). New England's 'Mystery Stone': New Hampshire Displays Unexplained Artifact 134 Years Later. Associated Press. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin H. (1936). "Was the Extinct Giraffe (Sivatherium) Known to the Early Sumerians?". American Anthropologist. 38 (4): 605–608. doi:10.1525/aa.1936.38.4.02a00100.

- ^ Naish, D. (2007) What happened with that Sumerian 'sivathere' figurine after Colbert's paper of 1936? Well, a lot. Tetrapod Zoology.

- ^ Müller-Karpe, Michael (1985). "Antlers of the Stag Rein Ring from Kish". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 44: 57–58. doi:10.1086/373105. S2CID 161093625.

- ^ Hristov, RH, and S. Genoves (2001) Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca. Dept. of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- ^ Schaaf, P and GA Wagner (1991) Comments on 'Mesoamerican Evidence of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts,' by Hristov and Genovés. Ancient Mesoamerica. 10:207–213.

- ^ Darling, David. "paleocontact hypothesis". The Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Debunking the Dendera "Light Bulb"". 3 October 2019.

- ^ "Awful Archaeology Ep. 5: The Dendera Light". YouTube.

- ^ Search for Hidden Light in the Pyramids

- ^ "The Tomb of Sabu and The Tri-lobed "Schist" Bowl". www.bibliotecapleyades.net. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ Grewe, Klaus. Der Eiserne Mann im Kottenforst. Rheinlandverlag, Cologne, 1978.

- ^ "IIT team solves the pillar mystery". The Times of India. 2005.

- ^ Cole, J.R. (Winter 1985). "If I Had a Hammer". Creation Evolution Journal. 5 (15). National Center for Science Education Inc.: 46–47.

One of his principal pieces of evidence for human contemporaneity with supposedly ancient geological strata is an iron hammer with a wooden handle found near London, Texas by others in the 1930s in an "Ordovician" stone concretion..."(Baugh, 1983b).

- ^ "The "Meister Print" An Alleged Human Sandal Print from Utah". TalkOrigins. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ Turner, Derek D.; Turner, Michelle I. (2021). ""I'm not saying it was aliens": an archaeological and philosophical analysis of a conspiracy theory". In Killin, Anton; Allen-Hermanson, Sean (eds.). Explorations in Archaeology and Philosophy. Springer. pp. 7–24. ISBN 978-3-030-61051-7.

- ^ McIntosh, Gregory C. (2000). The Piri Reis Map of 1513. University of Georgia Press. p. 230.

- ^ Dutch, Steven. "The Piri Reis Map". Archived from the original on 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ Brodie, Neil; Kersel, Morag M.; Tubb, Kathryn Walker (2006-08-01), "The Plunder of the Ulúa Valley, Honduras, and a Market Analysis For Its Antiquities", Archaeology, Cultural Heritage, and the Antiquities Trade, University Press of Florida, pp. 147–172, doi:10.5744/florida/9780813029726.003.0008, ISBN 9780813029726, retrieved 2022-04-20

- ^ Desmond, Kevin (20 September 2018). Electric Airplanes and Drones: A History. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4766-6961-8. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Weintraub, Pamela (1985). Omni's Catalog of the Bizarre. Doubleday. p. 24. ISBN 9780385192613.

- ^ Dunning, Brian (3 February 2015). "Skeptoid #452: The Stone Spheres of Costa Rica". Skeptoid.

- ^ Joffe, Alex (24 January 2018). "ANE TODAY – 201609 – Ask a Near Eastern Professional: How the Sumerians Got to Peru - American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR)". American Society of Overseas Research. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Stillman, B (1820) Curious Geological Facts: The American Journal of Science. v. 2, no. 1, pp. 144–146. (November 1820). Internet Archive copy archived on May 27, 2011.

- ^ Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K (2007) Tools in rock at Aix-en-Provence. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016.

- ^ Anonymous (2002) Mysterious Pipes Left by 'ET' Reported from Qinghai. People's Daily Online, Beijing, China. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Anonymous (2002) Chinese Scientists to Head for Suspected ET Relics. People's Daily Online, Beijing, China. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Dunning, Brian. "Skeptoid #181: The Baigong Pipes". Skeptoid. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Brookesmith, P (2004) The Eltanin Enigma. Archived 2013-04-03 at the Wayback Machine Fortean Times. (May 2004). Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Heezen, BC, and CD Hollister (1971) The Face of the Deep. Oxford University Press, New York. 659 pp. ISBN 0-19-501277-1

- ^ Hoagland, Richard C. (1996). The Monuments of Mars: A City on the Edge of Forever (4th ed.). Berkeley: Frog, Ltd. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-883319-30-4.

- ^ Cairncross, B (1988) "Cosmic cannonballs" a rational explanation: The South African Lapidary Magazine. v. 30, no. 1, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Heinrich, PV (1997) Mystery spheres: National Center for Science Education Reports. v. 17, no. 1, p. 34. (January/February 1997)

- ^ Bachelard, Michael (27 July 2013). "Digging for the truth at controversial megalithic site. Sydney Morning Herald, 27 July 2013". www.smh.com.au. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Wichmann, Wolf (2003-03-29). "Zeugnis einer untergegangenen Hochkultur Asiens oder einfach nur ein Felsklotz im Meer?: Das Yonaguni-Monument". Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 2019-06-16.

- ^ Peet, Preston (2013). Disinformation Guide to Ancient Aliens, Lost Civilizations, Astonishing Archaeology & Hidden History. Red Wheel Weiser. ISBN 978-1938875038.

- ^ "Noah's Ark Found in Turkey?". 2010-04-29. Archived from the original on 2010-04-29. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ Green, Lauren (2015-03-26). "Noah's Ark Hoax Claim Doesn't Deter Believers". Fox News. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ RealitateaTV (2014) "Specialist despre obiectul preistoric neidentificat din depozitele muzeului de istorie: 'aparţine unui robot primitiv'" Archived 2018-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, RealitateaTV.net.

- ^ Hilblairious (2014) "Aluminum, Aliens (1): What "THEY" left Behind in Aiud", Hilblairious.blogspot.ca.

- ^ Coulam, NJ, and AR Schroedl (1995) The Keystone azurite mine in southeastern Utah. Utah Archaeology. 8(1): 1–12.

- ^ Kuban, GJ, (2005) "Moab Man" – "Malachite Man". The Paluxy Dinosaur/"Man Track" Controversy. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Whipkey, Rockey (October 2012). "How deep do we dig? The pros and cons of a controversial ceramic figurine" (PDF). Pleistocene Coalition News. 4 (3).

- ^ Wright, George Frederick (1912). Origin and Antiquity of Man. Bibliotheca sacra Company. pp. 268–290.

- ^ Lippard, Jim (1989). "Out-of-Order Human Artifacts" (PDF). Creation/Evolution (25): 25.

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Jerome Agel (2000). Carl Sagan's Cosmic Connection. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 0-521-78303-8.

- ^ Evon, Dan (4 January 2016). "FALSE: 800-Year-Old Alien Cellphone Found". snopes. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Isaak, M. (2007). The Counter-Creationism Handbook. University of California Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0520249264.

- ^ Taylor, R. E.; Payen, Louis A.; Slota, Peter J. Jr (April 1992). "The Age of the Calaveras Skull: Dating the "Piltdown Man" of the New World". American Antiquity. 57 (2): 269–275. doi:10.2307/280732. JSTOR 280732. S2CID 162187935.

- ^ "An Alleged Revelation by Hull, the Giant Maker". Buffalo Morning Express. 1869-12-13. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ Rose, Mark (November–December 2005). "When Giants Roamed the Earth". Archeology. 58 (6). Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Craddock, Paul (2009). Scientific Investigation of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries. Oxford, UK and Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 415. ISBN 978-0750642057. OCLC 127107601.

- ^ "Egyptologist debunks new claims about 'Gosford glyphs'". ABC News. 14 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ "Jurassic library - The Ica Stones | Articles | Features | Fortean Times UK". 2008-08-27. Archived from the original on 2008-08-27. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- ^ "Oda Shizuo's 1985 Criticisms". www.t-net.ne.jp. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ "Calcite Weathering and the Age of the Kensington Rune Stone Inscription (Lightning Post)". Andy White Anthropology. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Feder (2011, pp. 159-62).

- ^ Ashurst-McGee, Mark (2001). "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics". BYU Studies. 40 (3): 178.

- ^ Lepper, Bradley (12 December 2014). "CONCLUSIVE PROOF THAT THE NEWARK DECALOGUE STONE IS A FORGERY (AND NOT A VERY GOOD ONE AT THAT)". Ohio History Connection. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ End as a Man. Time Magazine 30 Nov 1953 Archived 30 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 11 November 2010

- ^ Thompson, Raymond H. (2004). "Glimpses of the Young Emil Haury". Journal of the Southwest. 46 (1).

External links

[edit]- Critical perspective on Creationist and New Age claims related to out-of-place artifacts at Bad Archaeology

- Archaeology from the dark side at Salon.com

- Out-of-place artifacts article at Bad Archaeology