Gilgit-Baltistan

Gilgit-Baltistan

گلگت بلتستان | |

|---|---|

Region administered by Pakistan as an administrative territory | |

| |

Interactive map of Gilgit-Baltistan | |

| Coordinates: 35°21′N 75°54′E / 35.35°N 75.9°E | |

| Administering country | Pakistan |

| Established | 1 November 1948 (Gilgit-Baltistan Independence Day) |

| Capital | Gilgit |

| Largest city | Skardu[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Administrative territory |

| • Body | Government of Gilgit-Baltistan |

| • Governor | Syed Mehdi Shah |

| • Chief Minister | Gulbar Khan |

| • Chief Secretary | Ahmed Ali Mirza (BPS 21-PAS)[4] |

| • Legislature | Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly |

| • High Court | Supreme Appellate Court Gilgit-Baltistan[5] |

| Area | |

• Total | 72,496 km2 (27,991 sq mi) |

| [7] | |

| Population (2017) | |

• Total | 1,492,924[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PKT) |

| ISO 3166 code | PK-GB |

| Languages | Balti, Shina, Wakhi, Burushaski, Khowar, Domaki, Purgi, Changthang, Brokskat, Ladakhi, Urdu (administrative) |

| HDI (2019) | 0.592 Medium |

| Assembly seats | 33[9] |

| Divisions | 3 |

| Districts | 14[10] |

| Tehsils | 31[11] |

| Union Councils | 113 |

| Website | gilgitbaltistan |

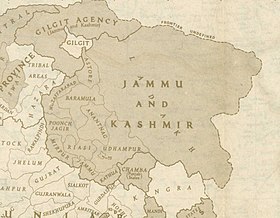

Gilgit-Baltistan (/ˌɡɪlɡɪt ˌbɔːltɪˈstɑːn, -stæn/; Urdu: گِلْگِت بَلْتِسْتان [12] ⓘ),[a] formerly known as the Northern Areas,[13] is a region administered by Pakistan as an administrative territory and consists of the northern portion of the larger Kashmir region, which has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947 and between India and China since 1959.[1] It borders Azad Kashmir to the south, the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west, the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan to the north, the Xinjiang region of China to the east and northeast, and the Indian-administered union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh to the southeast.

The region, together with Azad Kashmir in the southwest, is grouped and referred to by the United Nations and other international organisations as "Pakistan-administered Kashmir".[note 1] Gilgit-Baltistan is six times larger than Azad Kashmir in terms of geographical area.[18]

The territory of present-day Gilgit-Baltistan became a separate administrative unit in 1970 under the name "Northern Areas". It was formed by the amalgamation of the former Gilgit Agency, the Baltistan district, and several small former princely states, the largest of which were Hunza and Nagar.[19] In 2009, the region was renamed "Gilgit-Baltistan" and granted limited autonomy through the Self-Governance Order signed by then Pakistani president Asif Ali Zardari, a move that was reportedly intended to also empower the territory's people; however, scholars state that the real power rests with the governor and not with the chief minister or elected assembly.[20][21] Much of the population of Gilgit-Baltistan reportedly wants the territory to become integrated with Pakistan proper as a fifth province, and opposes integration with the rest of the Kashmir region.[22][23] The Pakistani government had rejected calls from the territory for provincial status on the grounds that granting such a request would jeopardise Pakistan's demands for the entire Kashmir conflict to be resolved according to all related United Nations resolutions.[24] However, in November 2020, Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan announced that Gilgit-Baltistan would attain provisional provincial status after the 2020 Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly election.[25][26][27]

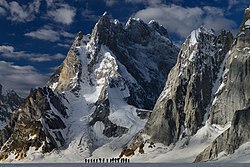

Gilgit-Baltistan covers an area of over 72,971 km2 (28,174 sq mi)[7] and is highly mountainous. It had an estimated population of 1.249 million people in 2013[28][29] (estimated to be 1.8 million in 2015 (Shahid Javed Burki (2015)). Its capital city is Gilgit with an estimated population of 216,760. The economy is dominated by agriculture and the tourism industry.[30] The region is home to five of the 14 eight-thousanders, including K2, and has more than fifty mountain peaks above 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). Three of the world's longest glaciers outside of Earth's polar regions are found in Gilgit-Baltistan. The main tourism activities are trekking and mountaineering, and this industry has been growing in importance throughout the region.

History

Early history

The rock carvings found in various places in Gilgit-Baltistan, especially in the Passu village of Hunza, suggest a human presence since 2000 BC.[32] Within the next few centuries of human settlement on the Tibetan plateau, this region became inhabited by Tibetans, who preceded the Balti people of Baltistan. Today Baltistan bears similarity to Ladakh physically and culturally (although not in religion). Dards are found mainly in the western areas. These people are the Shina-speaking peoples of Gilgit, Chilas, Astore and Diamir, while in Hunza and the upper regions, Burushaski and Khowar speakers predominate. The Dards find mention in the works of Herodotus,[note 2] Nearchus, Megasthenes, Pliny,[note 3] Ptolemy,[note 4] and the geographical lists of the Puranas.[33] In the 1st century, the people of these regions were followers of the Bon religion while in the 2nd century, they practised Buddhism.

Between 399 and 414, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Faxian visited Gilgit-Baltistan.[34] In the 6th century Somana Palola (greater Gilgit-Chilas) was ruled by an unknown king. Between 627 and 645, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang travelled through this region on his pilgrimage to India.

According to Chinese records from the Tang dynasty, between the 600s and the 700s, the region was governed by a Buddhist dynasty referred to as Bolü (Chinese: 勃律; pinyin: bólǜ), also transliterated as Palola, Patola, Balur.[35] They are believed to have been the Patola Shahis dynasty mentioned in a Brahmi inscription,[36] and devout adherents of Vajrayana Buddhism.[37] At the time, Little Palola (Chinese: 小勃律) was used to refer to Gilgit, while Great Palola (Chinese: 大勃律) was used to refer to Baltistan. However, the records do not consistently disambiguate the two.

In mid-600s, Gilgit came under Chinese suzerainty after the fall of the Western Turkic Khaganate to Tang military campaigns in the region. In the late 600s CE, the rising Tibetan Empire wrestled control of the region from the Chinese. However, faced with growing influence of the Umayyad Caliphate and then the Abbasid Caliphate to the west, the Tibetans were forced to ally themselves with the Islamic caliphates. The region was then contested by Chinese and Tibetan forces, and their respective vassal states, until the mid-700s.[38] Rulers of Gilgit formed an alliance with the Tang Chinese, and held back the Arabs with their help.[39]

Between 644 and 655, Navasurendrāditya-nandin became king of the Palola Sāhi dynasty in Gilgit.[40] Numerous Sanskrit inscriptions, including the Danyor Rock Inscriptions, were discovered to be from his reign.[41] In the late 600s and early 700s, Jayamaṅgalavikramāditya-nandin was king of Gilgit.[40]

According to Chinese court records, in 717 and 719 respectively, delegations of a ruler of Great Palola (Baltistan) named Su-fu-she-li-ji-li-ni (Chinese: 蘇弗舍利支離泥; pinyin: sūfúshèlìzhīlíní) reached the Chinese imperial court.[42][43] By at least 719/720, Ladakh (Mard) became part of the Tibetan Empire. By that time, Buddhism was practised in Baltistan, and Sanskrit was the written language.

In 720, the delegation of Surendrāditya (Chinese: 蘇麟陀逸之; pinyin: sūlíntuóyìzhī) reached the Chinese imperial court. He was referred to in Chinese records as the king of Great Palola; however, it is unknown if Baltistan was under Gilgit rule at the time.[44] The Chinese emperor also granted the ruler of Cashmere, Chandrāpīḍa ("Tchen-fo-lo-pi-li"), the title of "King of Cashmere". By 721/722, Baltistan had come under the influence of the Tibetan Empire.[45]

In 721–722, the Tibetan army attempted but failed to capture Gilgit or Bruzha (Yasin Valley). By this time, according to Chinese records, the king of Little Palola was Mo-ching-mang (Chinese: 沒謹忙; pinyin: méijǐnmáng). He had visited the Tang court requesting military assistance against the Tibetans.[44] Between 723 and 728, the Korean Buddhist pilgrim Hyecho passed through this area. In 737/738, Tibetan troops under the leadership of Minister Bel Kyesang Dongtsab of Emperor Me Agtsom took control of Little Palola. By 747, the Chinese army under the leadership of the ethnic-Korean commander Gao Xianzhi had recaptured Little Palola.[46] Great Palola was subsequently captured by the Chinese army in 753 under military Governor Feng Changqing. However, by 755, due to the An Lushan rebellion, the Tang Chinese forces withdrew and were no longer able to exert influence in Central Asia or in the regions around Gilgit-Baltistan.[47] The control of the region was left to the Tibetan Empire. They referred to the region as Bruzha, a toponym that is consistent with the ethnonym "Burusho" used today. Tibetan control of the region lasted until late-800s CE.[48]

Turkic tribes practising Zoroastrianism arrived in Gilgit during the 7th century, and founded the Trakhan dynasty in Gilgit.[39]

Medieval history

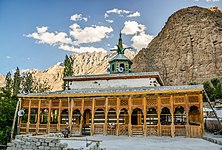

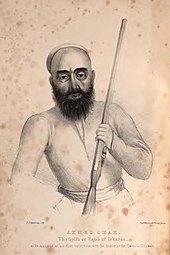

In the 14th century, Sufi Muslim preachers from Persia and Central Asia introduced Islam in Baltistan. Famous amongst them was Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, who came through Kashmir[49] while in the Gilgit region Islam entered in the same century through Turkic Tarkhan rulers. Gilgit-Baltistan was ruled by many local rulers, amongst whom the Maqpon dynasty of Skardu and the Rajas of Hunza were famous. The Maqpons of Skardu unified Gilgit-Baltistan with Chitral and Ladakh, especially in the era of Ali Sher Khan Anchan[50] who had friendly relations with the Mughal court.[51] Anchan's reign brought prosperity and entertained art, sport, and variety in architecture. He introduced polo to the Gilgit region, and sent a group of musicians from Chitral to Delhi to learn Indian music; Mughal architecture influenced the architecture of the region as well under his reign.[52] Later Anchan in his successors Abdal Khan had great influence though in the popular literature of Baltistan, where he is still alive as a dark figure by the nickname "Mizos", "man-eater". The last Maqpon Raja, Ahmed Shah, ruled all of Baltistan between 1811 and 1840. The areas of Gilgit, Chitral and Hunza had already become independent of the Maqpons.[citation needed]

Before the demise of Shribadat, a group of Shina people migrated from Gilgit Dardistan and settled in the Dras and Kharmang areas. The descendants of those Dardic people can be still found today, and are believed to have maintained their Dardic culture and Shina language up to the present time.[citation needed]

Under Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir

In November 1839, Dogra commander Zorawar Singh, whose allegiance was to Gulab Singh, started his campaign against Baltistan.[54] By 1840 he conquered Skardu and captured its ruler, Ahmad Shah. Ahmad Shah was then forced to accompany Zorawar Singh on his raid into Western Tibet. Meanwhile, Baghwan Singh was appointed as administrator (thanadar) in Skardu. But in the following year, Ali Khan of Rondu, Haidar Khan of Shigar and Daulat Ali Khan from Khaplu led a successful uprising against the Dogras in Baltistan and captured the Dogra commander Baghwan Singh in Skardu.[55]

In 1842, Dogra Commander Wasir Lakhpat, with the active support of Ali Sher Khan (III) from Kartaksho, conquered Baltistan for the second time. There was a violent capture of the fortress of Kharphocho. Haidar Khan from Shigar, one of the leaders of the uprising against the Dogras,[56] was imprisoned and died in captivity. Gosaun was appointed as administrator (Thanadar) of Baltistan and till 1860, the entire region of Gilgit-Baltistan was under the Sikhs and then the Dogras.[57][58]

After the defeat of the Sikhs in the First Anglo-Sikh War, the region became a part of the Jammu and Kashmir princely state, which since 1846 had remained under the rule of the Dogras. The population in Gilgit perceived itself as ethnically different from Kashmiris and disliked being ruled by the Kashmir state.[59] The region remained with the princely state, with temporary leases of some areas assigned to the British, until 1 November 1947.

First Kashmir War

After Pakistan's independence, Jammu and Kashmir initially remained an independent state. Later on 22 October 1947, tribal militias backed by Pakistan crossed the border into Jammu and Kashmir after Poonch rebellion and Jammu Muslim massacre.[60][61] Hari Singh made a plea to India for assistance and signed the Instrument of Accession, making his state a part of India. India air-lifted troops to defend the Kashmir Valley and the invaders were pushed back behind Uri.

Gilgit's population did not favour the State's accession to India.[62] The Muslims of the frontier ilaqas (Gilgit and the adjoining hill states) had wanted to join Pakistan.[63] Sensing their discontent, Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the Gilgit Scouts, mutinied on 1 November 1947, overthrowing the governor Ghansara Singh. The bloodless coup d'état was planned by Brown to the last detail under the code name "Datta Khel", which was also joined by a rebellious section of the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces under Mirza Hassan Khan. Brown ensured that the treasury was secured and minorities were protected. A provisional government (Aburi Hakoomat) was established by the Gilgit locals with Raja Shah Rais Khan as the president and Mirza Hassan Khan as the commander-in-chief. However, Major Brown had already telegraphed Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan asking Pakistan to take over. Pakistan's political agent, Khan Mohammad Alam Khan, arrived on 16 November and took over the administration of Gilgit.[64][65] Brown outmaneuvered the pro-Independence group and secured the approval of the mirs and rajas for accession to Pakistan.[66] According to Brown,

Alam replied [to the locals], "you are a crowd of fools led astray by a madman. I shall not tolerate this nonsense for one instance... And when the Indian Army starts invading you there will be no use screaming to Pakistan for help, because you won't get it."... The provisional government faded away after this encounter with Alam Khan, clearly reflecting the flimsy and opportunistic nature of its basis and support.[67]

The provisional government lasted 16 days. According to scholar Yaqub Khan Bangash, it lacked sway over the population. The Gilgit rebellion did not have civilian involvement and was solely the work of military leaders, not all of whom had been in favour of joining Pakistan, at least in the short term. Historian Ahmed Hasan Dani says that although there had been a lack of public participation in the rebellion, pro-Pakistan sentiments were intense in the civilian population and their anti-Kashmiri sentiments were also clear.[68] According to various scholars, the people of Gilgit as well as those of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, Punial, Hunza and Nagar joined Pakistan by choice.[69][70][71][72][73]

After taking control of Gilgit, the Gilgit Scouts along with Azad irregulars moved towards Baltistan and Ladakh and captured Skardu by May 1948. They successfully blocked Indian reinforcements sent to relieve Skardu, and proceeded towards Kargil and Leh. Indian forces mounted an offensive in the autumn of 1948 to push them back from Ladakh, but Baltistan came into the rebels' territory.[74][75]

On 1 January 1948, India took the issue of Jammu and Kashmir to the United Nations Security Council. In April 1948, the Council passed a resolution calling for Pakistan to withdraw from all of Jammu and Kashmir and for India to reduce its forces to the minimum level, following which a plebiscite would be held to ascertain the people's wishes.[76] However, no withdrawal was ever carried out. India insisted that Pakistan had to withdraw first and Pakistan contended there was no guarantee that India would withdraw afterwards.[77] Gilgit-Baltistan, along with the western districts that came to be called Azad Kashmir, have remained under the control of Pakistan ever since.[78]

Inside Pakistan

While the residents of Gilgit-Baltistan expressed a desire to join Pakistan after gaining independence from Maharaja Hari Singh, Pakistan declined to merge the region into itself because of the territory's link to Jammu and Kashmir.[72] For a short period after joining Pakistan, Gilgit-Baltistan was governed by Azad Kashmir if only "theoretically, but not practically" through its claim of being an alternative government for Jammu and Kashmir.[79] In 1949, the Government of Azad Kashmir handed over the administration of Gilgit-Baltistan to the federal government under the Karachi Agreement. According to Indian journalist Paul Sahni, this is seen as an effort by Pakistan to legitimise its rule over Gilgit-Baltistan.[80]

According to Pakistani analyst Ershad Mahmud, there were two reasons why administration was transferred from Azad Kashmir to Pakistan:

- the region was inaccessible from Azad Kashmir, and

- because both the governments of Azad Kashmir and Pakistan knew that the people of the region were in favour of joining Pakistan in a potential referendum over Kashmir's final status.[72]

According to the International Crisis Group, the Karachi Agreement is highly unpopular in Gilgit-Baltistan because Gilgit-Baltistan was not a party to it even while it was its own fate was being decided.[81]

From then until the 1990s, Gilgit-Baltistan was governed through the colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulations, which were originally created for the northwest tribal regions. They treated tribal people as "barbaric and uncivilised," levying collective fines and punishments.[82][83] People had no right to legal representation or appeal.[84][83] Members of tribes had to obtain prior permission from the police to travel anywhere, and had to keep the police informed about their movements.[85][86] There was no democratic set-up during this period. All political and judicial powers remained in the hands of the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Northern Areas (KANA). The people of Gilgit-Baltistan were deprived of rights enjoyed by citizens of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir.[87]

A primary reason for this state of affairs was the remoteness of Gilgit-Baltistan. Another factor was that the whole of Pakistan itself was deficient in democratic norms and principles, therefore the federal government did not prioritise democratic development in the region. There was also a lack of public pressure as an active civil society was absent in the region, with young educated residents usually opting to live in Pakistan's urban centers instead of staying in the region.[87]

Northern Areas

In 1970 the two parts of the territory, viz., the Gilgit Agency and Baltistan, were merged into a single administrative unit, and given the name "Northern Areas".[88][failed verification] The Shaksgam tract was ceded by Pakistan to China following the signing of the Sino-Pakistani Frontier Agreement in 1963.[89][90] In 1969, a Northern Areas Advisory Council (NAAC) was created, later renamed to Northern Areas Council (NAC) in 1974 and Northern Areas Legislative Council (NALC) in 1994. But it was devoid of legislative powers. All law-making was concentrated in the KANA Ministry of Pakistan. In 1994, a Legal Framework Order (LFO) was created by the KANA Ministry to serve as the de facto constitution for the region.[91][92]

In 1974, the former State Subject law was abolished in Gilgit Baltistan, and Pakistanis from other areas could buy land and settle.[93]

In 1984 the territory's importance shot up within Pakistan with the opening of the Karakoram Highway and the region's population became more connected to mainland Pakistan. The improved connectivity facilitated the local population to avail itself of educational opportunities in the rest of Pakistan.[94] Italso allowed the political parties of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir to set up local branches, raise political awareness in the region. According to Ershad Mahmud, these Pakistani political parties have played a 'laudable role' in organising a movement for democratic rights among the residents of Gilgit-Baltistan.[87]

In the 1988 Gilgit Massacre, groups of Islamist Sunnis, supported by Osama bin Laden, Pervez Musharraf, General Zia-ul Haq and Mirza Aslam Beg slaughtered hundreds of local Shias.[95]

Present structure

In the late 1990s, the President of Al-Jihad Trust filed a petition in the Supreme Court of Pakistan to determine the legal status of Gilgit-Baltistan. In its judgement of 28 May 1999, the Court directed the Government of Pakistan to ensure the provision of equal rights to the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, and gave it six months to do so. Following the Supreme Court decision, the government took several steps to devolve power to the local level. However, in several policy circles, the point was raised that the Pakistani government was helpless to comply with the court verdict because of the strong political and sectarian divisions in Gilgit-Baltistan and also because of the territory's historical connection with the still disputed Kashmir region, and that this prevented the determination of Gilgit-Baltistan's real status.[96]

A position of 'Deputy Chief Executive' was created to act as the local administrator, but the real powers still rested with the 'Chief Executive', who was the Federal Minister of KANA. "The secretaries were more powerful than the concerned advisors," in the words of one commentator. In spite of various reforms packages over the years, the situation is essentially unchanged.[97] Meanwhile, public rage in Gilgit-Baltistan "[grew] alarmingly." Prominent "antagonist groups" have mushroomed protesting the absence of civic rights and democracy.[98] The Pakistani government has debated granting provincial status to Gilgit-Baltistan.[99] Gilgit-Baltistan has been a member state of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization since 2008.[100] According to Antia Mato Bouzas, the PPP-led Pakistani government has attempted a compromise through its 2009 reforms between its traditional stand on the Kashmir dispute and the demands of locals, most of whom may have pro-Pakistan sentiments. While the 2009 reforms have added to the self-identification of the region, they have not resolved the constitutional status of the region within Pakistan.[101]

According to 2010 news reports, the people of Gilgit-Baltistan want to merge into Pakistan as a separate fifth province.[22][23] However, as of 2015 leaders of Azad Kashmir were opposed to any step towards integrating Gilgit-Baltistan into Pakistan.[102] The people of Gilgit-Baltistan have opposed integration with Azad Kashmir. They desire Pakistani citizenship and a constitutional status for their region.[22][23]

In 2016, for the first time in the country's Constitution, Gilgit-Baltistan had been mentioned by name.[103]

In September 2020, it was reported that Pakistan decided to elevate Gilgit-Baltistan's status to that of a full-fledged province.[104][105]

Government

The territory of present-day Gilgit-Baltistan became a separate administrative unit in 1970 under the name "Northern Areas". It was formed by the amalgamation of the former Gilgit Agency, the Baltistan District of the Ladakh Wazarat and the hill states of Hunza and Nagar. It presently consists of fourteen districts,[10][106] has a population approaching one million and an area of approximately 73,000 square kilometres (28,000 square miles), and shares borders with Pakistan, China, Afghanistan, and India. In 1993, an attempt was made by the High Court of Azad Jammu and Kashmir to annexe Gilgit-Baltistan but was quashed by the Supreme Court of Pakistan after protests by the locals of Gilgit-Baltistan, who feared domination by the Kashmiris.[24]

Government of Pakistan abolished State Subject Rule in Gilgit-Baltistan in 1974, which resulted in demographic changes in the territory.[107][108] While administratively controlled by Pakistan since the First Kashmir War, Gilgit-Baltistan has never been formally integrated into the Pakistani state and does not participate in Pakistan's constitutional political affairs.[109][110] On 29 August 2009, the Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order 2009, was passed by the Pakistani cabinet and later signed by the then President of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari.[111] The order granted self-rule to the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, by creating, among other things, an elected Gilgit-Baltistan Legislative Assembly and Gilgit-Baltistan Council. Gilgit-Baltistan thus gained a de facto province-like status without constitutionally becoming part of Pakistan.[109][112] Currently, Gilgit-Baltistan is neither a province nor a state. It has a semi-provincial status.[113] Traditionally, the Pakistani government had rejected Gilgit-Baltistani calls for integration with Pakistan on the grounds that it would jeopardise its demands for the whole Kashmir issue to be resolved according to UN resolutions.[24] However, since Imran Khan announced that it would be granted provisional provincial status, the Pakistani political parties finally agree to pass constitutional amendment to propose Gilgit-Baltistan as a province.[114][115] Some Kashmiri nationalist groups, such as the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, claim Gilgit-Baltistan as part of a future independent state to match what existed in 1947.[24] India, on the other hand, maintains that Gilgit-Baltistan is a part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that is "an integral part of the country [India]."[116]

Regions

Gilgit-Baltistan is administratively divided into three divisions: Baltistan, Diamer and Gilgit,[117] which, in turn, are divided into fourteen districts. The principal administrative centers are the towns of Gilgit and Skardu.

| Division | District | Area (km2) | Capital | Population (2013)[118] | Divisional Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltistan | Ghanche | 4,052 | Khaplu | 108,000 | Skardu |

| Shigar | 8,500 | Shigar | - | ||

| Kharmang | 5,500 | Kharmang | - | ||

| Skardu | 8,700 | Skardu | 305,000* | ||

| Roundu | NA | Dambudas | NA | ||

| Gilgit | Gilgit | 14,672 | Gilgit | 222,000 | Gilgit |

| Ghizer | 9,635 | Gahkuch | 190,000 | ||

| Hunza | 7,900 | Aliabad | 70,000 (2015)[119] | ||

| Nagar | 5,000 | Nagar | 51,387 (1998)[118] | ||

| Gupis–Yasin | NA | Phander? | NA | ||

| Diamer | Diamer | 10,936 | Chilas | 214,000 | Chilas |

| Astore | 5,092 | Eidghah | 114,000 | ||

| Darel | NA | Darel | NA | ||

| Tangir | NA | Tangir | NA |

* Combined population of Skardu, Shigar, Kharmang and Roundu districts. Shigar and Kharmang Districts were carved out of Skardu District after 1998. The estimated population of Gilgit-Baltistan was about 1.8 million in 2015[19] and the overall population growth rate between 1998 and 2011 was 63.1% making it 4.85% annually.[120][121]

Security

Security in Gilgit-Baltistan is provided by the Gilgit-Baltistan Police, the Gilgit Baltistan Scouts (a paramilitary force), and the Northern Light Infantry (part of the Pakistani Army).

The Gilgit-Baltistan Police (GBP) is responsible for law enforcement in Gilgit-Baltistan. The mission of the force is the prevention and detection of crime, maintenance of law and order and enforcement of the Constitution of Pakistan.

Geography and climate

Gilgit-Baltistan borders Pakistan's Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province to the west, a small portion of the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan to the north, China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to the northeast, the Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir to the southeast, and the Pakistani-administered state of Azad Jammu and Kashmir to the south.

Gilgit-Baltistan is home to all five of Pakistan's "eight-thousanders" and to more than fifty peaks above 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). Gilgit and Skardu are the two main hubs for expeditions to those mountains. The region is home to some of the world's highest mountain ranges. The main ranges are the Karakoram and the western Himalayas. The Pamir Mountains are to the north, and the Hindu Kush lies to the west. Amongst the highest mountains are K2 (Mount Godwin-Austen) and Nanga Parbat, the latter being one of the most feared mountains in the world.

Three of the world's longest glaciers outside the polar regions are found in Gilgit-Baltistan: the Biafo Glacier, the Baltoro Glacier, and the Batura Glacier. There are, in addition, several high-altitude lakes in Gilgit-Baltistan:

- Sheosar Lake in the Deosai Plains, Skardu

- Naltar lakes in the Naltar Valley, Gilgit

- Satpara Tso Lake in Skardu, Baltistan

- Katzura Tso Lake in Skardu, Baltistan

- Zharba Tso Lake in Shigar, Baltistan

- Phoroq Tso Lake in Skardu, Baltistan

- Lake Kharfak in Gangche, Baltistan

- Byarsa Tso Lake in Gultari, Astore

- Borith Lake in Gojal, upper Hunza, Gilgit

- Rama Lake near Astore

- Rush Lake near Nagar, Gilgit

- Kromber Lake at Kromber Pass, Ishkoman Valley, Ghizer District

- Barodaroksh Lake in Bar Valley, Nagar

- Ghorashi Lake in Ghandus Valley, Kharmang

The Deosai Plains are located above the tree line and constitute the second-highest plateau in the world after Tibet, at 4,115 metres (13,501 ft). The plateau lies east of Astore, south of Skardu and west of Ladakh. The area was declared as a national park in 1993. The Deosai Plains cover an area of almost 5,000 square kilometres (1,900 sq mi). For over half the year (between September and May), Deosai is snow-bound and cut off from rest of Astore and Baltistan in winters. The village of Deosai lies close to Chilum chokki and is connected with the Kargil district of Ladakh through an all-weather road.

-

Satpara Lake, Skardu, in 2002

-

Upper Kachura Lake

-

Shangrila Lake, Skardu

Rock art and petroglyphs

There are more than 50,000 pieces of rock art (petroglyphs) and inscriptions all along the Karakoram Highway in Gilgit-Baltistan, concentrated at ten major sites between Hunza and Shatial. The carvings were left by invaders, traders, and pilgrims who passed along the trade route, as well as by locals. The earliest date back to between 5000 and 1000 BCE, showing single animals, triangular men and hunting scenes in which the animals are larger than the hunters. These carvings were pecked into the rock with stone tools and are covered with a thick patina that proves their age.

The ethnologist Karl Jettmar has pieced together the history of the area from inscriptions and recorded his findings in Rock Carvings and Inscriptions in the Northern Areas of Pakistan[122] and the later-released Between Gandhara and the Silk Roads — Rock Carvings Along the Karakoram Highway.[123] Many of these carvings and inscriptions will be inundated and/or destroyed when the planned Basha-Diamir dam is built and the Karakoram Highway is widened.

Climate

The climate of Gilgit-Baltistan varies from region to region, since the surrounding mountain ranges create sharp variations in weather. The eastern part has the moist zone of the western Himalayas, but going toward Karakoram and Hindu Kush, the climate gets considerably drier.[124]

There are towns like Gilgit and Chilas that are very hot during the day in summer yet cold at night and valleys like Astore, Khaplu, Yasin, Hunza, and Nagar, where the temperatures are cold even in summer.[125]

Climate Change Effects

Climate change has adversely effected this region with more rains every year. On 26 August 2022, most villages in Ghizer district and Hunza were severely effected by the ongoing flooding displacing many people.

Economy and resources

The economy of the region is primarily based on a traditional trade route, the historic Silk Road. The China Trade Organization forum led the people of the area to actively invest and learn modern trade know-how from their Chinese neighbour, Xinjiang.[citation needed] Later, the establishment of a chamber of commerce and the Sust dry port in Gojal Hunza are milestones. The rest of the economy is shouldered by mainly agriculture and tourism. Agricultural products are wheat, corn (maize), barley, and fruits. Tourism is mostly in trekking and mountaineering, and this industry is growing in importance.[126][127] As of August 2021[update], the gross state product (GSP) nominal of Gilgit-Baltistan was $2.5 billion and GSP (nominal) per capita of Gilgit-Baltistan was $1,748.[128] GSP purchasing power parity (PPP) of Gilgit-Baltistan was $10 billion and GSP (PPP) per capita of GB was $6,028.[128]

In early September 2009, Pakistan signed an agreement with the People's Republic of China for a major energy project in Gilgit-Baltistan which includes the construction of a 7,000-megawatt dam at Bunji in the Astore District.[112] The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor connects Xinjiang and the hinterland of Pakistan through Gilgit-Baltistan, and the Government of Pakistan hopes that residents of Gilgit-Baltistan will benefit from CPEC and other development projects.[105][129]

Mountaineering

Gilgit-Baltistan is home to more than 20 peaks of over 6,100 metres (20,000 ft), including K-2 the second highest mountain on Earth.[131] Other well known peaks include Masherbrum (also known as K1), Broad Peak, Hidden Peak, Gasherbrum II, Gasherbrum IV, and Chogolisa, situated in Khaplu Valley. The following peaks have so far been scaled by various expeditions:

| Name of Peak | Photos | Height | First known ascent | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.K-2 |  |

(28,250 ft) | 31 July 1954 | Karakoram |

| 2. Nanga Parbat |  |

(26,660 ft) | 3 July 1953 | Himalaya |

| 3. Gasherbrum I |  |

(26,360 ft) | 7 July 1956 | Karakoram |

| 4. Broad Peak |  |

(26,550 ft) | 9 June 1957 | Karakoram |

| 5. Muztagh Tower |  |

(23,800 ft) | 6 August 1956 | Karakoram |

| 6. Gasherbrum II |

|

(26,120 ft) | 4 July 1958 | Karakoram |

| 7. Hidden Peak |  |

(26,470 ft) | 4 July 1957 | Karakoram |

| 8. Khunyang Chhish |  |

(25,761 ft) | 4 July 1971 | Karakoram |

| 9. Masherbrum |  |

(25,659 ft) | 4 August 1960 | Karakoram |

| 10. Saltoro Kangri |  |

(25,400 ft) | 4 June 1962 | Karakoram |

| 11. Chogolisa |

|

(25,148 ft) | 4 August 1963 | Karakoram |

Basic facilities

Gilgit has not received a gas pipeline infrastructure since Pakistan's independence, unlike other cities. Through the importation of gas cylinders from other provinces, many private gas contractors offer gas cylinders. The LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) Air Mix Plant project by Sui Northern Gas Pipelines Limited was unveiled in 2020 with the goal of bringing the gas facility to Gilgit. This will significantly reduce deforestation as public uses wood from trees for heating and lighting purpose. The first head office has been built in Gilgit City.[132]

Tourism

Gilgit Baltistan is the capital of tourism in Pakistan. Gilgit Baltistan is home to some of the highest peaks in the world, including K2 the second highest peak in the world. Gilgit Baltistan's landscape includes mountains, lakes, glaciers and valleys. Gilgit Baltistan is not only known for its mountains — it is also visited for its landmarks, culture, history and people.[133] K2 Basecamp, Deosai, Naltar, Fairy Meadows Bagrot Valley and Hushe valley are common places to visit in Gilgit Baltistan.[134]

Transport

Before 1978, Gilgit-Baltistan was cut off from the rest of the Pakistan and the world due to the harsh terrain and the lack of accessible roads. All of the roads to the south opened toward the Pakistan-administered state of Azad Kashmir and to the southeast toward the present-day Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. During the summer, people could walk across the mountain passes to travel to Rawalpindi. The fastest way to travel was by air, but air travel was accessible only to a few privileged local people and to Pakistani military and civilian officials. Then, with the assistance of the Chinese government, Pakistan began construction of the Karakoram Highway (KKH), which was completed in 1978. The journey from Rawalpindi / Islamabad to Gilgit takes approximately 20 to 24 hours.

The Karakoram Highway connects Islamabad to Gilgit and Skardu, which are the two major hubs for mountaineering expeditions in Gilgit-Baltistan. Northern Areas Transport Corporation (NATCO) offers bus and jeep transport service to the two hubs and several other popular destinations, lakes, and glaciers in the area. Landslides on the Karakoram Highway are very common. The Karakoram Highway connects Gilgit to Tashkurgan Town, Kashgar, China via Sust, the customs and health-inspection post on the Gilgit-Baltistan side, and the Khunjerab Pass, the highest paved international border crossing in the world at 4,693 metres (15,397 ft).

In March 2006, the respective governments announced that, commencing on 1 June 2006, a thrice-weekly bus service would begin across the boundary from Gilgit to Kashgar and road-widening work would begin at 600 kilometres (370 mi) of the Karakoram Highway. There would also be one daily bus in each direction between the Sust and Taxkorgan border areas of the two political entities.[135]

Pakistan International Airlines used to fly a Fokker F27 Friendship daily between Gilgit Airport and Benazir Bhutto International Airport. The flying time was approximately 50 minutes, and the flight was one of the most scenic in the world, as its route passed over Nanga Parbat, a mountain whose peak is higher than the aircraft's cruising altitude. However, the Fokker F27 was retired after a crash at Multan in 2006. Currently, flights are being operated by PIA to Gilgit on the brand-new ATR 42–500, which was purchased in 2006. With the new plane, the cancellation of flights is much less frequent. Pakistan International Airlines also offers regular flights of a Boeing 737 between Skardu and Islamabad. All flights are subject to weather clearance; in winter, flights are often delayed by several days.

A railway through the region has been proposed; see Khunjerab Railway for details.

Demographics

Population

The population of Gilgit Baltistan is 1,492,924 as of 2017.[2] The estimated population of Gilgit-Baltistan in 2013 was 1.249 million,[28][29] and it was 873,000 in 1998.[136] Approximately 14% of the population was urban.[137] The fertility rate is 4.7 children per woman, which is the highest in Pakistan.[138]

The population of Gilgit-Baltistan consists of many diverse linguistic, ethnic, and religious sects, due in part to the many isolated valleys separated by some of the world's highest mountains. The ethnic groups include Shins, Yashkuns, Kashmiris, Kashgaris, Pamiris, Pathans, and Kohistanis.[139] A significant number of people from Gilgit-Baltistan are residing in other parts of Pakistan, mainly in Punjab and Karachi. The literacy rate of Gilgit-Baltistan is approximately 72%.

In 2017 census, Gilgit District has the highest population of 330,000 and Hunza District the lowest of 50,000.[136]

Languages

Gilgit-Baltistan is a multilingual region where Urdu being a national and official language serves as the lingua franca for inter ethnic communications. English is co-official and also used in education, while Arabic is used for religious purposes. The table below shows a break-up of Gilgit-Baltistan first-language speakers.

| Rank | Language | Detail[140][141][142][143][144][145][146][147] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shina | It is a Dardic language spoken by the majority in six tehsils (Gilgit, Diamir/Chilas, Darel/Tangir, Astore, Puniyal/Gahkuch and Rondu). |

| 2 | Balti | It is spoken by the majority in five tehsils (Skardu/Shigar, Kharmang, Gultari, Khaplu and Mashabrum). It is from the Tibetan language family and has Urdu borrowings. |

| 3 | Burushaski | It is spoken by the majority in four tehsils (Nagar 1, Hunza/Aliabad, Nagar II, and Yasin). It is a language isolate that has borrowed considerable Urdu vocabulary. |

| 4 | Khowar | It is spoken by the majority in two tehsils (Gupis and Ishkomen) but also spoken in Yasin and Puniyal/Gahkuch Tehsils. Like Shina, it is a Dardic language. |

| 5 | Wakhi | It is spoken by the majority of people in Gojal Tehsil of Hunza. But it is also spoken in the Yasin and Ishkomen tehsils of Gupis-Yasin and Ghizer districts. It is classified as eastern Iranian/ Pamiri language. |

| Unranked | Others | Pashto, Kashmiri, Domaaki (spoken by musician clans in the region) and Gojri languages are also spoken by a significant population of the region. |

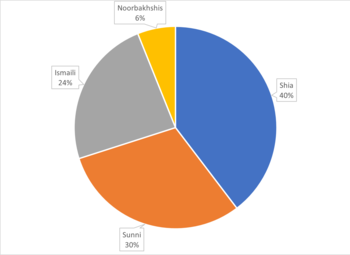

Religion

The population of Gilgit-Baltistan is entirely Muslim and is denominationally the most diverse in the country. The region is also the only Shia-plurality area in an otherwise Sunni-dominant Pakistan.[149] People in the Skardu district are mostly Shia, while Diamir and Astore districts have Sunni majorities. Ghanche has a Noorbakhshi population, and Ghizar has an Ismaili majority.[150] The populations in Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar districts are composed of a mix of all of these sects.[148] Recent surveys show that Shia Ismaili women, both rural and urban, have high rates of contraceptives usage and low fertility rates; by contrast Sunni women, especially in rural areas, have low rates of contraceptive usage and high fertility rates.[151]

| Religious group |

1891[152] | 1901[153] | 1911[154] | 1921[155] | 1931[156] | 1941[157] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |||

| Islam |

110,161 | 86.68% | 58,779 | 96.54% | 77,189 | 98.45% | 88,643 | 98.82% | 94,940 | 98.44% | 115,601 | 99.62% | ||

| Tribal | 16,615 | 13.07% | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0% | ||

| Buddhism |

239 | 0.19% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Hinduism |

77 | 0.06% | 2,001 | 3.29% | 1,112 | 1.42% | 948 | 1.06% | 1,361 | 1.41% | 295 | 0.25% | ||

| Christianity |

2 | 0% | 28 | 0.05% | 22 | 0.03% | 16 | 0.02% | 49 | 0.05% | 28 | 0.02% | ||

| Sikhism |

0 | 0% | 74 | 0.12% | 81 | 0.1% | 90 | 0.1% | 93 | 0.1% | 121 | 0.1% | ||

| Jainism |

0 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Zoroastrianism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Judaism |

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0% | ||

| Others | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Total population | 127,094 | 100% | 60,885 | 100% | 78,404 | 100% | 89,697 | 100% | 96,446 | 100% | 116,047 | 100% | ||

| Note1: 1891 figure taken from census data using the total population of Skardu District and Gilgit District in the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir that ultimately would be administered by Pakistan, in the contemporary administrative territory of Gilgit–Baltistan. Note2: 1901 figure taken from census data using the total population of Gilgit District in the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir that ultimately would be administered by Pakistan, in the contemporary administrative territory of Gilgit–Baltistan. Note3: 1911–1931 figures taken from census data by combining the total population of Gilgit District and the Frontier Ilaqas in the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir that ultimately would be administered by Pakistan, in the contemporary administrative territory of Gilgit–Baltistan. Note4: 1941 figure taken from census data by combining the total population of one district (Astore) and one agency (Gilgit) in the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir that ultimately would be administered by Pakistan, in the contemporary administrative territory of Gilgit–Baltistan. | ||||||||||||||

Culture

Gilgit-Baltistan is home to diversified cultures, ethnic groups, languages and backgrounds.[158] Major cultural events include the Shandoor Polo Festival, Babusar Polo Festival and Jashn-e-Baharan or the Harvest Time Festival (Navroz).[158] Traditional dances include: Old Man Dance in which more than one person wears old-style dresses; Cow Boy Dance (Payaloo) in which a person wears old style dress, long leather shoes and holds a stick in hand and the Sword Dance in which the participants show taking one sword in right and shield in left. One to six participants can dance in pairs.

Sports

Many types of sports are in currency, throughout the region, but most popular of them is Polo.[159][160] Almost every bigger valley has a polo ground, polo matches in such grounds attract locals as well as foreigners visitors during summer season. One of such polo tournament is held in Shandur each year and polo teams of Gilgit with Chitral participates.[161] Though very internationally unlikely, but even for some local historians like Hassan Hasrat from Skardu and for some national writers like Ahmed Hasan Dani it was originated in same region.[162] For testimonies, they present the Epic of King Gesar of balti version where king gesar started polo by killing his step son and hit head of cadaver with a stick thus started the game[163] they also held that the very simple rules of local polo game also testifies its primitiveness. The English word Polo has Balti origin, that is spoken in same region, dates back to the 19th century which means ball.[164][165]

Other popular sports are football, cricket, volleyball (mostly play in winters) and other minor local sports. with growing facilities and particular local geography Climbing, trekking and other similar sports are also getting popularity. Samina Baig from Hunza valley is the only Pakistani woman and the third Pakistani to climb Mount Everest and also the youngest Muslim woman to climb Everest, having done so at the age of 21 while Hassan Sadpara from Skardu valley is the first Pakistani to have climbed six eight-thousanders including the world's highest peak Everest (8848 m) besides K2 (8611 m), Gasherbrum I (8080 m), Gasherbrum II (8034 m), Nanga Parbat (8126 m), Broad Peak (8051 m).

Notable people

- Amen Aamir, first woman from Gilgit-Baltistan to qualify as a pilot

See also

- Northern Pakistan

- List of cities in Gilgit Baltistan

- List of cultural heritage sites in Gilgit-Baltistan

- List of mountains in Pakistan

Notes

- ^ The Indian government and Indian sources refer to Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan as "Pakistan-occupied Kashmir" ("PoK")[14] or "Pakistan-held Kashmir" ("PhK").[15] Sometimes Azad Kashmir alone is meant by these terms.[14] "Pakistan-administered Kashmir" and "Pakistan-controlled Kashmir"[16][17] are used by neutral sources. Conversely, Pakistani sources refer to the territories under Indian control as "Indian-occupied Kashmir" ("IoK") or "Indian-held Kashmir" ("IhK").[14]

- ^ He twice mentions a people called Dadikai, first along with the Gandarioi, and again in the catalogue of king Xerxes's army invading Greece. Herodotus also mentions the gold-digging ants of Central Asia.

- ^ In the 1st century, Pliny repeats that the Dards were great producers of gold.

- ^ Ptolemy situates the Daradrai on the upper reaches of the Indus

References

- ^ a b The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the tertiary sources (a) through (e), reflecting due weight in the coverage. Although "controlled" and "held" are also applied neutrally to the names of the disputants or to the regions administered by them, as evidenced in sources (h) through (i) below, "held" is also considered politicised usage, as is the term "occupied," (see (j) below).

(a) Kashmir, region Indian subcontinent, Encyclopaedia Britannica, archived from the original on 13 August 2019, retrieved 15 August 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "Kashmir, region of the northwestern Indian subcontinent ... has been the subject of dispute between India and Pakistan since the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. The northern and western portions are administered by Pakistan and comprise three areas: Azad Kashmir, Gilgit, and Baltistan, the last two being part of a territory called the Northern Areas. Administered by India are the southern and southeastern portions, which constitute the state of Jammu and Kashmir but are slated to be split into two union territories.";

(b) Pletcher, Kenneth, Aksai Chin, Plateau Region, Asia, Encyclopaedia Britannica, archived from the original on 2 April 2019, retrieved 16 August 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "Aksai Chin, Chinese (Pinyin) Aksayqin, portion of the Kashmir region, at the northernmost extent of the Indian subcontinent in south-central Asia. It constitutes nearly all the territory of the Chinese-administered sector of Kashmir that is claimed by India to be part of the Ladakh area of Jammu and Kashmir state.";

(c) "Kashmir", Encyclopedia Americana, Scholastic Library Publishing, 2006, p. 328, ISBN 978-0-7172-0139-6, archived from the original on 17 January 2023, retrieved 6 November 2019 C. E Bosworth, University of Manchester Quote: "KASHMIR, kash'mer, the northernmost region of the Indian subcontinent, administered partly by India, partly by Pakistan, and partly by China. The region has been the subject of a bitter dispute between India and Pakistan since they became independent in 1947";

(d) Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003), Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Taylor & Francis, pp. 1191–, ISBN 978-0-415-93922-5, archived from the original on 17 January 2023, retrieved 12 June 2023 Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir: Territory in northwestern India, subject to a dispute between India and Pakistan. It has borders with Pakistan and China."

(e) Talbot, Ian (2016), A History of Modern South Asia: Politics, States, Diasporas, Yale University Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 978-0-300-19694-8 Quote: "We move from a disputed international border to a dotted line on the map that represents a military border not recognized in international law. The line of control separates the Indian and Pakistani administered areas of the former Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir.";

(f) Skutsch, Carl (2015) [2007], "China: Border War with India, 1962", in Ciment, James (ed.), Encyclopedia of Conflicts Since World War II (2nd ed.), London and New York: Routledge, p. 573, ISBN 978-0-7656-8005-1,The situation between the two nations was complicated by the 1957–1959 uprising by Tibetans against Chinese rule. Refugees poured across the Indian border, and the Indian public was outraged. Any compromise with China on the border issue became impossible. Similarly, China was offended that India had given political asylum to the Dalai Lama when he fled across the border in March 1959. In late 1959, there were shots fired between border patrols operating along both the ill-defined McMahon Line and in the Aksai Chin.

(g) Clary, Christopher (2022), The Difficult Politics of Peace: Rivalry in Modern South Asia, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, p. 109, ISBN 9780197638408,Territorial Dispute: The situation along the Sino-Indian frontier continued to worsen. In late July (1959), an Indian reconnaissance patrol was blocked, "apprehended," and eventually expelled after three weeks in custody at the hands of a larger Chinese force near Khurnak Fort in Aksai Chin. ... Circumstances worsened further in October 1959, when a major class at Kongka Pass in eastern Ladakh led to nine dead and ten captured Indian border personnel, making it by far the most serious Sino-Indian class since India's independence.

(h) Bose, Sumantra (2009), Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Harvard University Press, pp. 294, 291, 293, ISBN 978-0-674-02855-5 Quote: "J&K: Jammu and Kashmir. The former princely state that is the subject of the Kashmir dispute. Besides IJK (Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir. The larger and more populous part of the former princely state. It has a population of slightly over 10 million, and comprises three regions: Kashmir Valley, Jammu, and Ladakh.) and AJK ('Azad" (Free) Jammu and Kashmir. The more populous part of Pakistani-controlled J&K, with a population of approximately 2.5 million.), it includes the sparsely populated "Northern Areas" of Gilgit and Baltistan, remote mountainous regions which are directly administered, unlike AJK, by the Pakistani central authorities, and some high-altitude uninhabitable tracts under Chinese control."

(i) Fisher, Michael H. (2018), An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge University Press, p. 166, ISBN 978-1-107-11162-2 Quote: "Kashmir's identity remains hotly disputed with a UN-supervised "Line of Control" still separating Pakistani-held Azad ("Free") Kashmir from Indian-held Kashmir.";

(j) Snedden, Christopher (2015), Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris, Oxford University Press, p. 10, ISBN 978-1-84904-621-3 Quote:"Some politicised terms also are used to describe parts of J&K. These terms include the words 'occupied' and 'held'." - ^ a b "Gilgit-Baltistan". City Population. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "Skardu". Skardu. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Nagri, Jamil (26 October 2023). "Gilgit-Baltistan gets new chief secretary". Dawn. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "Supreme Appellate Court GB". sacgb.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Sökefeld, Martin (2015), "At the margins of Pakistan: Political relationships between Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir", in Ravi Kalia (ed.), Pakistan's Political Labyrinths: Military, Society and Terror, Routledge, p. 177, ISBN 978-1-317-40544-3: "While AJK formally possesses most of the government institutions of a state, GB now formally has the institutions of a Pakistani province. However, AJK remains a quasi-state and GB a quasi-province because neither territory enjoys the full rights and powers connected with the respective political formations. In both areas, Pakistan retains ultimate control."

- ^ a b "UNPO: Gilgit Baltistan: Impact Of Climate Change On Biodiversity". unpo.org. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Legislative Assembly will have directly elected 24 members, besides six women and three technocrats. "Gilgit Baltistan: New Pakistani Package or Governor Rule Archived 25 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine" 3 September 2009, The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO)

- ^ a b "GB notifies four more districts, total number of districts now 14", Pakistan Today, 17 June 2019, archived from the original on 15 June 2020, retrieved 16 March 2020

- ^ "Gilgit-Baltistan at a Glance, 2020" (PDF). PND GB. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2021.

- ^ "گلگت بلتستان اسمبلی کادوسرا اجلاس". Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly (in Urdu). 19 December 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Hinman, Bonnie (15 September 2011), We Visit Pakistan, Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc., p. 41, ISBN 978-1-61228-103-2, archived from the original on 21 July 2023, retrieved 20 June 2016

- ^ a b c Snedden 2013, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Chandra, Bipan; Mukherjee, Aditya; Mukherje, Mridula (2008). India since Independence. Penguin Books India. p. 416. ISBN 978-0143104094.

- ^ Bose, Sumantra (2009). Contested lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus and Sri Lanka. Harvard University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0674028562.

- ^ Behera 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Dutta, Prabhash K. (25 March 2017). "Gilgit-Baltistan: Story of how region 6 times the size of PoK passed on to Pakistan". India Today. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ a b Shahid Javed Burki 2015.

- ^ In Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, residents see experiment with autonomy as 'illusion' Archived 20 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Christian Science Monitor, 28 November 2011

- ^ Sering, Senge H. (2010), "Constitutional Impasse in Gilgit-Baltistan (Jammu and Kashmir): The Fallout", Strategic Analysis, 34 (3): 354–358, doi:10.1080/09700161003658998, ISSN 0970-0161, S2CID 154847994,

Instead of the chief minister, the order rests all administrative, political and judicial authority with the governor, which makes him the supreme authority and portrays the assembly as a toothless tiger. At best, the order legitimises Pakistan's occupation and claims political rights for the locals without changing the power equation.

- ^ a b c Singh, Pallavi (29 April 2010). "Gilgit-Baltistan: A question of autonomy". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

But it falls short of the main demand of the people of Gilgit- Baltistan for a constitutional status to the region as a fifth province and for Pakistani citizenship to its people.

- ^ a b c Shigri, Manzar (12 November 2009). "Pakistan's disputed Northern Areas go to polls". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

Many of the 1.5 million people of Gilgit-Baltistan oppose integration into Kashmir and want their area to be merged into Pakistan and declared a separate province.

- ^ a b c d Schofield, Victoria (2000). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan, and the Unending War. I.B. Tauris. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9781860648984.

- ^ "Fifth province". Fifth province | The Express Tribune. The Express Tribune. 2 November 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Pakistani PM says he will upgrade status of part of Kashmir, angering India". Pakistani PM says he will upgrade status of part of Kashmir, angering India | Reuters. Reuters. 1 November 2020. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Gilgit-Baltistan to get provisional provincial status post-election: PM Imran". Gilgit-Baltistan to get provisional provincial status post-election: PM Imran. The News International. 2 November 2020. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ a b Geography & Demography of Gilgit Baltistan Archived 5 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Gilgit Baltistan Scouts, retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ a b Under Pakistan Rule, Gilgit-Baltistan Most Neglected, Backward Area in South Asia, Says New Book Archived 30 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, News18, 18 August 2019.

- ^ Paracha, Nadeem F. (22 December 2016). "Here is why Pakistan is more diverse than you thought". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Episode 1: A Window to Gilgit-Baltistan". 4 July 1997. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ By Ian Hibbert (17 November 2015). Alpamayo to Everest: It's Not About the Summit. Lulu Publishing Services. ISBN 9781483440736.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Petech, Luciano (1977). The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 A.D. Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente.

- ^ By Rafi U. Samad (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat ... Algora. ISBN 9780875868592.

- ^ Sen, Tansen (2015). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of India–China Relations, 600–1400. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442254732. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Schmidt, Ruth Laila; Kohistani, Razwal (2008). A Grammar of the Shina Language of Indus Kohistan. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447056762. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Twist, Rebecca L. (2007). Patronage, Devotion and Politics: A Buddhological Study of the Patola Sahi Dynasty's Visual Record. Ohio State University. ISBN 9783639151718. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Stein, Mark Aurel (1907). Ancient Khotan: Detailed Report of Archaeological Explorations in Chinese Turkestan. Vol. 1. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. 4–18.

- ^ a b Bradnock, Robert W. (1994). South Asian Handbook. Trade & Travel Publications. p. 1168.

- ^ a b Neelis, Jason (2011). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks. Brill. p. 177. ISBN 9789004181595. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^

Stein, Aurel (2011). "Archæological Notes form the Hindukush Region". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 76 (1–2): 5–24. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00098713. ISSN 0035-869X. S2CID 163127705.

Sri-Nava-Surendraditya-Nandideva

- ^ "Baltistan". Tibetan Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ 董誥. . [Complete collection of Tang prose] (in Chinese). Vol. 0039 – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b . [New Book of Tang] (in Chinese). Vol. 221 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Francke, August Hermann (1992). Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part 1. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120607699.

- ^ Grousset, René (1952). The Rise and Splendour of the Chinese Empire. p. 160.

- ^ By Angela Falco Howard (2006). Chinese Sculpture. Yale University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0300100655.

- ^ Mock, John (October 2013). "A Tibetan Toponym from Afghanistan" (PDF). Revue d'Études Tibétaines (27): 5–9. ISSN 1768-2959. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ By Henry Osmaston, Philip Denwood (1995). Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5: Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth ... Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120814042.

- ^ P. Stobdan (April 2008). The last colony: Muzaffarabad-Gilgit-Baltistan. India Research Press with Centre for Strategic and Regional Studies, University of Jammu. ISBN 9788183860673.

- ^ International Council on Archives, National Archives of Pakistan (1990). Guide to the Sources of Asian History: National archives, Provincial archives, District archives. National Archives of Pakistan. ISBN 9789698156022.

- ^ Philippe Fabry, Yousuf Shahid (1995). Wandering with the Indus. Ferozsons. ISBN 9789690102249.

- ^ Francke, August Hermann (1907), A History of Western Tibet: One of the Unknown Empires, Asian Educational Services, pp. 164–, ISBN 978-81-206-1043-9

- ^ By S.R. Bakshi (1997). Kashmir: History and People. Sarup & Sons. p. 158. ISBN 9788185431963.

- ^ By Sanjeev Kumar Bhasi (2006). Amazing Land Ladakh: Places, People, and Culture. Indus. ISBN 9788173871863.

- ^ By Shridhar Kaul, H. N. Kaul (1992). Ladakh Through the Ages, Towards a New Identity. Indus. ISBN 9788185182759.

- ^ Bubandt, Nils Ole; Beek, Martijn Van (12 March 2012). Varieties of Secularism in Asia: Anthropological Explorations of Religion, Politics and the Spiritual. Routledge. ISBN 9781136668647 – via Google Books.

- ^ By Peter Berger, Frank Heidemann (3 June 2013). The Modern Anthropology of India: Ethnography, Themes and Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134061112.

- ^ Bangash 2010, pp. 125–126.

- ^ "Quick guide: Kashmir dispute". BBC News. 29 June 2006. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ^ "Who changed the face of '47 war?". The Times of India. 14 August 2005. Archived from the original on 1 June 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2005.

- ^ Bangash 2010, p. 128: [Ghansara Singh] wrote to the prime minister of Kashmir: 'in case the State accedes to the Indian Union, the Gilgit province will go to Pakistan', but no action was taken on it, and in fact Srinagar never replied to any of his messages.

- ^ Snedden 2013, p. 14, "Similarly, Muslims in Western Jammu Province, particularly in Poonch, many of whom had martial capabilities, and Muslims in the Frontier Districts Province strongly wanted Jammu and Kashmir to join Pakistan."

- ^ Schofield 2003, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Bangash 2010.

- ^ Schofield, Victoria (2000). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-86064-898-4.

- ^ Bangash 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Bangash 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Bangash 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Bangash, Yaqoob Khan (9 January 2016). "Gilgit-Baltistan—part of Pakistan by choice". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

Nearly 70 years ago, the people of the Gilgit Wazarat revolted and joined Pakistan of their own free will, as did those belonging to the territories of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin and Punial; the princely states of Hunza and Nagar also acceded to Pakistan. Hence, the time has come to acknowledge and respect their choice of being full-fledged citizens of Pakistan.

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-85065-700-2.

- ^ a b c Mahmud 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Sokefeld, Martin (November 2005), "From Colonialism to Postcolonial Colonialism: Changing Modes of Domination in the Northern Areas of Pakistan" (PDF), The Journal of Asian Studies, 64 (4): 939–973, doi:10.1017/S0021911805002287, S2CID 161647755, archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2020, retrieved 14 December 2019

- ^ Schofield 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Bajwa, Farooq (2013), From Kutch to Tashkent: The Indo-Pakistan War of 1965, Hurst Publishers, pp. 22–24, ISBN 978-1-84904-230-7

- ^ Bose, Tapan K. (2004). Raṇabīra Samāddāra (ed.). Peace Studies: An Introduction To the Concept, Scope, and Themes. Sage. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-7619-9660-6.

- ^ Varshney, Ashutosh (1992), "Three Compromised Nationalisms: Why Kashmir has been a Problem" (PDF), in Raju G. C. Thomas (ed.), Perspectives on Kashmir: the roots of conflict in South Asia, Westview Press, p. 212, ISBN 978-0-8133-8343-9

- ^ Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2008). Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-415-46839-8.

- ^ Snedden 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Sahni 2009, p. 73.

- ^ Discord in Pakistan's Northern Areas 2007, p. 5.

- ^ Bansal 2007, p. 60.

- ^ a b "From the fringes: Gilgit-Baltistanis silently observe elections". Dawn. 1 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Priyanka Singh 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Raman 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Behera 2007, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Mahmud 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Weightman, Barbara A. (2 December 2005). Dragons and Tigers: A Geography of South, East, and Southeast Asia (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-471-63084-5.

- ^ Chellaney, Brahma (2011). Water: Asia's New Battleground. Georgetown University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-58901-771-9.

- ^ "China's Interests in Shaksgam Valley". Sharnoff's Global Views. 10 October 2013. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Discord in Pakistan's Northern Areas 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Mahmud 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ^ "GB's aspirations". Dawn. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021.

- ^ Mahmud 2008, p. 25-26.

- ^ Levy & Scott-Clark, Deception (2010), Chapter 13: "Undaunted, Musharraf had in 1988 been called on by General Beg to put down a Shia riot in Gilgit, in the north of Pakistan. Rather than get the Pakistan army bloodied, he inducted a tribal band of Pashtun and Sunni irregulars, many from the SSP which had recently put out a contract on Bhutto, led by the mercenary Osama bin Laden (who had been hired by Hamid Gul to do the same four years earlier)."

- ^ Mahmud 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Mahmud 2008, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Mahmud 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Mahmud, Ershad (24 January 2016). "Gilgit-Baltistan: A province or not". The News on Sunday. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "UNPO: Gilgit Baltistan". unpo.org. 11 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Bouzas, Antia Mato (2012). "Mixed Legacies in Contested Borderlands: Skardu and the Kashmir Dispute". Geopolitics. 17 (4): 867–886. doi:10.1080/14650045.2012.660577. S2CID 73717097.

- ^ Naqash, Tariq (9 July 2015). "AJK opposes giving provincial status to GB". Dawn. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

MUZAFFARABAD: Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) Prime Minister Chaudhry Abdul Majeed warned the federal government on Wednesday against any attempt to convert Gilgit-Baltistan into a province of Pakistan.

- ^ "Pak desire to integrate Gilgit-Baltistan may help solve Kashmir Tangle; NDT submission". mail.pakistanchristianpost.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ "Pakistan to make Gilgit-Baltistan a full-fledged province: report". The Hindu. 17 September 2020. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b Mukhopadhyaya, Ankita (13 November 2020). "Pakistan's Gilgit-Baltistan 'province': Will it make the Kashmir dispute irrelevant?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Dividing governance: Three new districts notified in G-B". The Express Tribune. 5 February 2017. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Those Troubled Peaks". 11 May 2015. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Mehdi, Tahir (16 June 2015). "GB's aspirations". Dawn. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Gilgit-Baltistan: A question of autonomy". Indian Express. 21 September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Shigri, Manzar (12 November 2009). "Pakistan's disputed Northern Areas go to polls". Reuters.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Pakistani president signs Gilgit-Baltistan autonomy order _English_Xinhua". News.xinhuanet.com. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Gilgit-Baltistan autonomy". Dawn. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Gilgit Baltistan Geography, History, Politics and Languages". 19 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Abbas, Ghulam (21 February 2022). "Govt accelerates move to grant GB provincial status". Profit by Pakistan Today. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Plan finalised to give G-B provisional status of province". Brecorder. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Gilgit-Baltistan part of Jammu and Kashmir: India". The Times of India. 10 March 2006. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Gilgit-Baltistan divided into three divisions". The Express Tribune. 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Gilgit-Baltistan: Districts & Places – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". City Population. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Shafqat Hussain 2015.

- ^ "Pak population increased by 46.9% between 1998 and 2011". The Times of India. PTI. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Statistical Booklet on Gilgit-Baltistan" (PDF). Government of Gilgit-Baltistan, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "Rock Carvings and Inscriptions along the Karakorum Highway (Pakistan) –- a brief introduction". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ "Between gandhara and the silk roads". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ "Climate of Gilgit-Baltistan (formerly Northern Areas)". WWF Pakistan. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "Weather of Gilgit, Skardu, Chitral, Chilas, Islamabad | Gilgit Baltistan - promoting culture and tourism". Gilgit Baltistan. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Baltistan (region, Northern Areas, Kashmir, Pakistan)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ "Gilgit (Kashmir region, Indian subcontinent)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ a b Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Bureau of Statistics (August 2021). "GDP OF KHYBER PUKHTUNKHWA'S DISTRICTS MEASURING ECONOMIC ACTIVITY USING NIGHTLIGHTS" (PDF). KPK Government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ Yusra, Khan. "The Economic Benefits of CPEC for Gilgit Baltistan". Centre For Peace, Security and Developmental Studies. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to PAKISTANALPINE.COM". pakistanalpine.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Baltistan in History, Banat Gul Afridi

- ^ "The Pride - Official Newsletter of SNGPL" (PDF). Sui Northern Gas Pipelines Limited. 13 (9): 9. November 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Skardu, pk. "Top 10 Most beautiful plces to visit in Pakistan". Skardu.pk. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "5 Most Beautiful Places To Visit in Gilgit Baltistan". Skardu.pk. www.skardu.pk. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ "Kashgar-Gilgit bus service planned". Dawn. 23 March 2006. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Census shows patterns the same across LoC". 21 September 2017. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Population, poverty and environment" (PDF). Northern Areas Strategy for Sustainable Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2004. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ ""Exploring the potential for fertility change: A ranking of districts based on socio-demographic conduciveness to family planning"" (PDF). United Nations Population Fund. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Pakistan's Fragile Foundations". Council on Foreign Relations. 12 March 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "International Programs". Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Khowar – South Asia Blog". 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Katy, Gardner (1999). Leif O. Manger (ed.). Muslim diversity: local Islam in global contexts. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7007-1104-8.

- ^ "Election : Gilgit-Baltistan – 8 Languages, 10 Ethnic Groups, 6 Districts, 4 Religious sects – 24 National Assembly Seats ! – GILGIT BALTISTAN (GB)". 22 January 2010. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1993), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2,

... he agreed with Grierson in seeing Rajasthani influence on Pahari and 'Dardic' influence on (or under) the whole Northwestern group + Pahari [...] Sindhi and including 'Lahnda', Dardic, Romany and West Pahari, there has been a tendency to transfer of 'r' from medial clusters to a position after the initial consonant ...

- ^ Munshi, S. (2008), Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (eds.), Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7, archived from the original on 24 March 2023, retrieved 11 May 2010,

Based on historical sub-grouping approximations and geographical distribution, Bashir (2003) provides six sub-groups of the Dardic languages ...

- ^ Malik, Amar Nath (1995), The phonology and morphology of Panjabi, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN 978-81-215-0644-1, retrieved 26 May 2010,

... drakhat 'tree' ...

- ^ electricpulp.com. "DARDESTĀN". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Sectarian conflict in Gilgit-Baltistan" (PDF). pildat. May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Naumann & Fischer-Tahir 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker & Priscilla Roberts 2008, p. 917.

- ^ Milena Marchesi, Silvia De Zordo, ed. (5 February 2016). Reproduction and Biopolitics: Ethnographies of Governance, Rationality and Resistance. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317618041.

- ^ "Census of India, 1891. Volume XXVIII, The Kashmir state : the report on the census and imperial and supplementary tables". 1891. p. 213. JSTOR saoa.crl.25352828. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. Vol. 23A, Kashmir. Pt. 2, Tables". 1901. p. 20. JSTOR saoa.crl.25366883. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1911. Vol. 20, Kashmir. Pt. 2, Tables". 1911. p. 17. JSTOR saoa.crl.25394111. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 22, Kashmir. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. p. 15. JSTOR saoa.crl.25430177. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1931. Vol. 24, Jammu & Kashmir State. Pt. 2, Imperial & state tables". 1931. p. 267. JSTOR saoa.crl.25797120. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1941. Vol. 22, Jammu & Kashmir". 1941. pp. 337–352. JSTOR saoa.crl.28215644. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Culture and Heritage of Gilgit". visitgilgitbaltistan.gov.pk. Gov.Pk. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Amanullah Khan (1999). Gilgit Baltistan, a disputed territory or a fossil of intrigues?.

- ^ F. M. Khan (2002). The story of Gilgit, Baltistan and Chitral: a short history of two millenniums AD 7-1999.

- ^ James H. Mills, ed. (2005). Subaltern Sports: Politics and Sport in South Asia. Anthem. p. 77. ISBN 9781843311683.

- ^ De Filippi, Filippo; Luigi Amedeo di Savoia (1912). Karakoram and Western Himalaya 1909. Dutton.

polo was originated in baltistan.