U.S. national anthem protests

Protests during the playing of the United States national anthem have had many causes, including civil rights, anti-conscription, anti-war, anti-nationalism, and religious reservations. Such protests have occurred since at least the 1890s, well before "The Star-Spangled Banner" was adopted and resolved by Congress as the official national anthem in 1916 and 1931, respectively. Earlier protests typically took place during the performance of various unofficial national anthems, including "My Country, 'Tis of Thee" and "Hail, Columbia". These demonstrations may include refusal to stand or face the American flag during the playing of the Anthem. Some of the protestors object to honoring the slaveowner and author of the lyrics, Francis Scott Key.

On political grounds

[edit]Early examples

[edit]In 1892, three men, including a friend of Ida B. Wells, were lynched by a white mob while in police custody in Memphis, Tennessee, in an event known as the People's Grocery lynching. This act sparked a national outcry. At a meeting of one thousand people at Bethel A. M. E. Church, Reverend W. Gaines called for the crowd to sing the then de facto national anthem, "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," but the call was refused, one member of the audience declaring, "I don't want to sing that song until this country is what it claims to be, 'sweet land of liberty'".[1][2] The Reverend substituted the Civil War-era song about the abolitionist martyr, "John Brown's Body". Well's husband, Ferdinand L. Barnett, closed the meeting appealing for calm and a careful response, but also expressing great frustration and concern that the violence against blacks may one day lead to reprisals.[1][2]

Early 20th century

[edit]

Refusal to stand during the national anthem became a widespread form of protest during World War I. In some cases, this was related to protest of conscription.[3] Newspapers at the time associated the protests with support for socialism,[4][5] Bolshevism,[6] or communism. In one case, supporters of anarchist Emma Goldman refused to stand for the national anthem.[7] The act of protest was very controversial, and many people were highly offended, so that even accidentally remaining seated could result in violence.[8]

Protests during the anthem continued after World War I. For example, during the build-up towards World War II, a group of students at Haverford College in Philadelphia refused to stand because they felt the custom was leading to "rabid nationalism".[9] In 1943 in Arizona, a federal judge ruled that members of Jehovah's Witnesses cannot be suspended from school for refusing to stand during the national anthem.[10]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]

In the 1960s, refusal to stand during the anthem took place for a number of reasons. In the late 1960s, the protest became increasingly common among athletes and at schools, both as an opposition to the Vietnam War and as a protest of nationalism. Some of the cases involving students included the following. In December 1968, Chris Wood, co-captain of the Adelbert College basketball team was removed from the team for not standing, saying, "We believe in the fellowship of man. We don't believe in nationalism."[11] Five white high school students were suspended in Cumberland, Maryland in February 1970.[12] A federal judge Joseph P. Kinneary ordered reinstatement of a pair of students in Columbus, Ohio, saying that forcing anyone to participate in "symbolic patriotic ceremonies" against their will was a violation of the First Amendment to the US Constitution.[13] In 1978, on The New York Times, Daniel A. Jenkins suggested "making it a Federal offense to have it [the anthem] played at any professional sporting event of any kind" to better serve "a nation sick to death of war".[14][15]

From 1968 onwards, Jimi Hendrix performed an instrumental version using feedback, distortion and other effects to deconstruct the music with the sonic images of rockets and bombs. Common interpretations link this to an opposition to the Vietnam War, as opposed to Hendrix's own explanation: "We're all Americans ... it was like 'Go America!' ... We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see".[16]

Donald Sutherland, Gary Goodrow, Peter Boyle, and Jane Fonda developed an anti-war comedy show which featured a skit about people refusing to stand during the anthem which toured about 20 cities in 1971.[17]

Civil rights activities

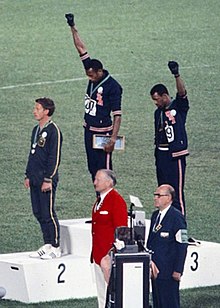

[edit]At the same time, Civil Rights became an important cause which led to anthem protests. The 1968 Olympics Black Power salute was a political demonstration conducted by African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City. After having won gold and bronze medals, respectively, in the 200 meter running event, they turned on the podium to face their flags, and to hear the American national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner". Each athlete raised a black-gloved fist, and kept them raised until the anthem had finished. In addition, Smith, Carlos, and Australian silver medalist Peter Norman all wore human rights badges on their jackets. In his autobiography, Silent Gesture, Smith stated that the gesture was not a "Black Power" salute, but a "human rights salute". The event is regarded as one of the most overtly political statements in the history of the modern Olympic Games.[18][19]

In 1969, University of Wyoming coach Lloyd Eaton dismissed 14 black football players who requested to wear black armbands to protest the racial slurs they faced during games, particularly against BYU. When the two teams played in 1971, about 50 students at UW refused to stand during the national anthem and wore black armbands during the game.[20] Another place where African Americans refused to stand during the anthem in 1971 was at Northern Illinois University basketball games, which led to widespread criticism.[21]

The protests became widespread, and in some cases, arrangements were made for the anthem to be played before athletes left the locker room. Lew Alcindor, later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, began to refuse to stand at UCLA basketball games, and in response the anthem was played before the players left the locker room in the UCLA-University of Washington game.[22] UCLA's coach John Wooden denied that Alcindor or any other UCLA player he coached had refused to stand for the anthem, while sometimes the anthem was played while the team was in the locker room or even during warm ups.[23] The same was done when the five starters of Florida State University's basketball team, all African American, played Tulane University in 1971 in New Orleans.[24]

At the 1972 Summer Olympics, two American 400 m runners, Vincent Matthews (gold medalist) and Wayne Collett (silver medalist), staged a protest on the victory podium, talking to each other and failing to stand at attention during the medal ceremony.[25] They were banned by the IOC, as Tommie Smith and John Carlos had been in the 1968 Summer Olympics. Since John Smith had pulled a hamstring in the final and had been ruled unfit to run, the United States were forced to scratch from the 4×400 m relay.

Civil rights based protests continued into the late 1970s. In 1978, a student was barred from receiving his diploma in Dayton, Ohio for refusing to sing.[26]

Turn of the millennium

[edit]On August 24, 1990, Irish pop singer Sinéad O'Connor threatened to boycott her scheduled performance that night at the Garden State Arts Center in Holmdel Township, New Jersey, if the U.S. national anthem were played. In her own words, she explained,

I sincerely harbor no disrespect for America or Americans, but I have a policy of not having any national anthems played before my concerts in any country, including my own, because they have nothing to do with music in general ... I am concerned though, because today, we're seeing other artists arrested at their own concerts ... There is a disturbing trend towards censorship of music and art in this country and people should be alarmed over that far more than my actions ...

The Center gave in to her demands, but not without controversy. Frank Sinatra criticized her the following evening while performing at the same venue, stating that he wished that he could "kick her in the ass." New York state Senator Nicholas Spano urged people to boycott O'Connor's subsequent show in Saratoga, saying "I'm sure Ms. O'Connor would be the first to complain if someone tried to censor her performance, yet she is trying to censor the national anthem by refusing to perform where it is played."[27]

In the NBA in 1996, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, guard for the Denver Nuggets, refused to stand during the anthem before games in protest of anti-Islamic rhetoric. He was suspended for his actions and received hostile responses and death threats.[28][29][30] It was noted at the same time that the Seattle SuperSonics’ Sam Perkins, a Jehovah's Witness, stood apart from his teammates during the national anthem. George Shinn, owner of the Charlotte Hornets, threatened to trade any player who refused to stand.[31][32] After his suspension, Abdul-Rauf stood, but with his head bowed in silent prayer.[33]

In 2003, two women's basketball players, Toni Smith of Manhattanville College and Deidra Chatman of the University of Virginia, made headlines for refusing to face the flag during the national anthem. Chatman protested for one game in March 2003 due to her anti-war views in light of the then-ongoing tensions between the U.S. and Iraq.[34] Smith, who had been boycotting the anthem all season long before being finally noticed in February 2003, said that she was also protesting the United States' involvement in Iraq, as well as a growing disparity between the rich and the poor. During one of her team's games on February 23, 2003, a fan named Jerry Kiley, a self-described Vietnam veteran, ran onto the court and confronted her with an American flag, saying, "She has not earned the right to disrespect the flag."[35]

In 2004, Carlos Delgado of the Toronto Blue Jays Major League Baseball team decided he would no longer stand during the song, "God Bless America," out of protest at America's wars in the Middle East.[32]

2016–present

[edit]

During 2016, several professional athletes protested police brutality during the United States (U.S.) national anthem. The protests began in the National Football League (NFL) after San Francisco 49ers quarterback (QB) Colin Kaepernick sat during the anthem, as opposed to the tradition of standing, before his team's third preseason game of 2016. At first, Kaepernick's quiet demonstrations went unnoticed until a former Army Green Beret named Nate Boyer suggested the quarterback kneel as a more respectful sign toward veterans, which is exactly what made Kaepernick stand out. People started to notice a kneeling player, rather than one who was hidden behind standing players while he sat on the bench.[36] The protests have generated mixed reactions and have since spread to other U.S. sports leagues.

Shortly after, his demonstrations spread nationwide to sports on every level, including college football and volleyball, high school football, a Texas youth football team, along with Major League Baseball's (MLB) Oakland A's, the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the U.S. national women's soccer team.[37] Stemming from the Kaepernick controversy, before the beginning of the 2016 World Cup of Hockey tournament in Toronto, Canada, Team USA coach John Tortorella told in an interview that if any one of his players were to sit out during the anthem, they would sit on the bench for the entire duration of the game.[38] By the time the first Sunday of the regular season started in September 2016, several other players starting taking part in Kaepernick's protests, including: his teammate Eric Reid, Seattle Seahawks' Jeremy Lane, Denver Broncos' Brandon Marshall (who lost three endorsement deals for his actions), four Miami Dolphins players, Kansas City Chief's Marcus Peters, and New England Patriots' Martellus Bennett and Devin McCourty. When various players first took part in these acts, the NFL came out with a statement saying that individual teams would receive a fine if its players sat or knelt during the anthem.[39] Kaepernick's Twitter and Instagram platforms were soon filled with acknowledgements about the racial injustice and brutality against young African American men. He publicized his reasoning for why he chose to kneel during the National Anthem. As the protests continued, Colin Kaepernick, the man who started the protests, was featured on the October cover of Time Magazine for stirring up conversations regarding his movement. In September 2018, Nike made Kaepernick the face of its campaign- Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything- which promoted debate over his protests and boycotts against Nike. [40]

On the grounds of spectators' experience

[edit]Sports spectators felt the anthem performance was integrated poorly to the sports game. In 1989, on the New York Times, an opinion wrote, "Nowadays, sports promoters don't even try to get people to participate [by singing along] and the anthem is either presented like an aria from Tannhauser or used as a launch pad for a rock star's ego trip."[41][15]

Many sports spectators afraid of being yelled for not conforming sing along as a "joyless act performed for the sake of keeping out of trouble", which relegated the performance to a "mass display of ritualized obedience" and "performative patriotism". It is also argued that playing the anthem thousands of times a year before every sporting event makes the anthem not as special as it deserves to be. Hence, saving the anthem for truly deserving circumstances would make the anthem a genuinely patriotic experience.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Not Their Country, The Decatur Herald (Decatur, Illinois) March 29, 1892, page 1". The Decatur Herald. 1892-03-29. p. 1. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ a b "Wouldn't Sing America," The Evening World (New York, New York) March 28, 1892, page 3". The Evening World. 1892-03-28. p. 3. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From The St. Louis Star and Times". The St. Louis Star and Times. 1917-06-01. p. 3. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Asked to Resign, The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California) October 30, 1917, page 13". The Los Angeles Times. 1917-10-30. p. 13. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From The Oregon Daily Journal". The Oregon Daily Journal. 1918-06-18. p. 4. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From Harrisburg Telegraph". Harrisburg Telegraph. 1918-12-09. p. 16. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Reds Turned Out at Trial of Emma, The Sun (New York, New York) July 7, 1917, page 4". The Sun. 1917-07-07. p. 4. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From The St. Louis Star and Times". The St. Louis Star and Times. 1917-12-10. p. 3. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, The Evening News". Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, The Evening News. 1934-05-31. p. 21. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From The San Bernardino County Sun". The San Bernardino County Sun. 1963-08-30. p. 11. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From El Paso Herald-Post". El Paso Herald-Post. 1968-12-11. p. 24. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Clipped From The Daily Courier". The Daily Courier. 1970-02-25. p. 19. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Anthem Protest Pair Reinstated, Lubbuck Avalanche-Journal (Lubbock, Texas) July 8, 1970, page 75". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. 1970-07-08. p. 75. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ Jenkins, Daniel A. (4 July 1978). "A Rational Anthem". New York Times. p. 24.

- ^ a b Spiegel, Allen D.; Spiegel, Marc B. (1998). "Redundant patriotism: The United States national anthem as an obligatory sports ritual". Culture, Sport, Society (1): 32.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 271.

- ^ "Anti-War Show has SRO Crowd, The Troy Record (Troy, New York) March 15, 1927, page 1". The Troy Record. 1971-03-15. p. 1. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ Lewis, Richard (8 October 2006). "Caught in Time: Black Power salute, Mexico, 1968". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen L. (2017-09-24). "They didn't #TakeTheKnee: The Black Power protest salute that shook the world in 1968". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ Wyoming President Says Black 14 Issues Remain, The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah) October 21, 1971, page 19, accessed October 21, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7116500//

- ^ Banning Anthem Discraceful Action, Belvidere Daily Republican (Belvidere, Illinois) December 20, 1971, page 6, accessed October 21, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7116534//

- ^ Walt Brown, Athletes, Celebrities Personal Moments: The 60s and 70s, AuthorHouse, Mar 10, 2016

- ^ Hy Gardner, "Glad You Asked That," The Indiannapolis Star, Dec. 06, 1969, 86 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/62382199/alcindor-at-ucla-stand-for-anthem/

- ^ FSU Starters Refuse to Stand for Anthem, Albuquerque Journal (Albuquerque, New Mexico) January 14, 1971, page 25, accessed October 21, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7116445//

- ^ Schiller, K.; Young, C. (2010). The 1972 Munich Olympics and the Making of Modern Germany. Weimar and now. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26213-3. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ "Won't Sing Anthem, so no Diploma, The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois) June 4, 1978, page 10". The Pantagraph. 1978-06-04. p. 10. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "Legislator Urges Boycott Over Sinead's Anthem Ban". Los Angeles Times. Times Wire Services. p. 10. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Home, Hostile Home, New York Times (August 8, 2013)

- ^ Jim Hodges (March 13, 1996). "NBA Sits Abdul-Rauf for Stance on Anthem". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Sarah J. Black Celebrity, Racial Politics, and the Press: Framing Dissent. Routledge, 2014. p117-118

- ^ McCallum, Jack, "Oh Say Should We Sing?" Sports Illustrated, March 25, 1996, accessed October 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Abrams, Roger I. Playing Tough: The World of Sports and Politics. UPNE, 2013. p4

- ^ Abrams 2014, p 125

- ^ Reedy, Jim (March 4, 2003). "U-Va. Protest Takes an About Face". Washington Post. WP Company. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Pennington, Bill (February 26, 2003). "Player's Protest Over the Flag Divides Fans". New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ "All you need to know about why NFL players are taking a knee and where it came from". The Independent. 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Gregory, Sean (22 September 2016). "October 3rd, 2016 | Vol. 188, No. 13". Time. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ "Tortorella 'will sit' any Team USA player who protests anthem - Sportsnet.ca". Sportsnet.ca. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- ^ Gregory, Sean (22 September 2016). "October 3rd, 2016 | Vol. 188, No. 13". Time. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ "Colin Kaepernick kneeling timeline: How protests during the national anthem started a movement in the NFL". www.sportingnews.com. 13 September 2020. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Redding, James (22 July 1989). "Give Us a Better National Anthem and We'll Sing". New York Times. p. 24. Archived from the original on 2015-05-25.

- ^ Fisher, Anthony L. (2021-02-13). "For the love of America, stop playing the national anthem before sporting events". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2021-02-13.

- Cross, Charles R. (2005). Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix. Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-8841-2.

- Anti-racism in the United States

- Anti-war movement

- Civil rights protests in the United States

- U.S. national anthem protests (2016–present)

- Islam and politics

- Beliefs and practices of Jehovah's Witnesses

- Music and politics

- Police brutality in the United States

- Politics and race in the United States

- Politics and sports

- Protests in the United States

- Religion and politics

- Sports controversies

- The Star-Spangled Banner

- Athlete activism in the United States