Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna | |

|---|---|

Painting of Nāgārjuna from the Shingon Hassozō, a series of scrolls authored by the Shingon school of Buddhism. Japan, Kamakura Period (13th-14th century) | |

| Born | c. 150 CE |

| Died | c. 250 CE India |

| Occupation(s) | Buddhist teacher, monk and philosopher |

| Known for | Credited with founding the Madhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism |

Nāgārjuna (c. 150 – c. 250 CE; simplified Chinese: 龙树; traditional Chinese: 龍樹; pinyin: Lóngshù; Template:Lang-bo) was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered as one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.[2] Furthermore, according to Jan Westerhoff, he is also "one of the greatest thinkers in the history of Asian philosophy."[3]

Nāgārjuna is widely considered to be the founder of the madhyamaka (centrism, middle-way) school of Buddhist philosophy and a defender of the Mahāyāna movement.[2][4] His Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Root Verses on Madhyamaka, MMK) is the most important text on the madhyamaka philosophy of emptiness. The MMK inspired a large number of commentaries in Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan, Korean and Japanese and continues to be studied today.[5]

History

Background

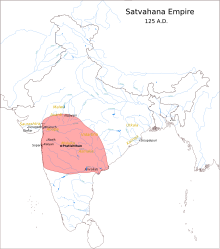

India in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE was divided into various states, including the Kushan Empire and the Satavahana Kingdom. At this point in Buddhist history, the Buddhist community was already divided into various Buddhist schools and had spread throughout India.

At this time, there was already a small and nascent Mahāyāna movement. Mahāyāna ideas were held by a minority of Buddhists in India at the time. As Joseph Walser writes, "Mahāyāna before the fifth century was largely invisible and probably existed only as a minority and largely unrecognized movement within the fold of nikāya Buddhism."[6] By the second century, early Mahāyāna Sūtras such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā were already circulating among certain Mahāyāna circles.[7]

Life

Very little is reliably known of the life of Nāgārjuna and modern historians do not agree on a specific date (1st to 3rd century CE) or place (multiple places in India suggested) for him.[8] The earliest surviving accounts were written in Chinese and Tibetan centuries after his death and are mostly hagiographical accounts that are historically unverifiable.[8]

Some scholars such as Joseph Walser argue that Nāgārjuna was an advisor to a king of the Sātavāhana dynasty which ruled the Deccan Plateau in the second century.[9][10] This is supported by most of the traditional hagiographical sources as well.[11] Archaeological evidence at Amarāvatī indicates that if this is true, the king may have been Yajña Śrī Śātakarṇi (c. second half of the 2nd century). On the basis of this association, Nāgārjuna is conventionally placed at around 150–250 CE.[9][10]

Walser thinks that it is most likely that when Nāgārjuna wrote the Ratnavali, he lived in a mixed monastery (with Mahāyānists and non-Mahāyānists) in which Mahāyānists were the minority. The most likely sectarian affiliation of the monastery according to Walser was Purvasailya, Aparasailya, or Caityaka (which were Mahāsāṃghika sub-schools).[12]

He also argues that "it is plausible that he wrote the Ratnavali within a thirty-year period at the end of the second century in the Andhra region around Dhanyakataka (modern-day Amaravati)."[9]

Traditional hagiography

According to Walser, "the earliest extant legends about Nāgārjuna are compiled into Kumārajīva’s biography of Nāgārjuna, which he translated into Chinese in about 405 c.e."[11] According to this biography, Nāgārjuna was born into a Brahmin family[13] in Vidarbha[14][15][16] (a region of Maharashtra) and later became a Buddhist. The traditional religious hagiographies place Nāgārjuna in various regions of India (Kumārajīva and Candrakirti place him in South India, Xuanzang in south Kosala).[11]

Traditional religious hagiographies credit Nāgārjuna with being associated with the teaching of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras as well as with having revealed these scriptures to the world after they had remained hidden for some time. The sources differ on where this happened and how Nāgārjuna retrieved the sutras. Some sources say he retrieved the sutras from the land of the nāgas.[17]

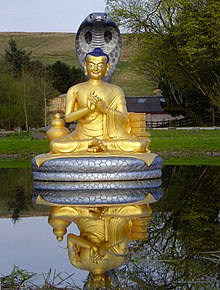

Indeed, Nāgārjuna is often depicted in composite form comprising human and nāga characteristics. Nāgas are snake-like supernatural beings of great magical power that feature in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain mythology.[18] Nāgas are found throughout Indian religious culture, and typically signifies an intelligent serpent or dragon, who is responsible for the rains, lakes and other bodies of water. In Buddhism, it is a synonym for a realised arhat, or wise person in general.[19]

Traditional sources also claim that Nāgārjuna practiced aryuvedic alchemy (rasayāna). Kumārajīva's biography for example, has Nāgārjuna making an elixir of invisibility, and Bus-ton, Taranatha and Xuanzang all state that he could turn rocks into gold.[20]

Tibetan hagiographies also state that Nāgārjuna studied at Nālanda University. However, according to Walser, this university was not a strong monastic center until about 425. Also, as Walser notes, "Xuanzang and Yijing both spent considerable time at Nālanda and studied Nāgārjuna’s texts there. It is strange that they would have spent so much time there and yet chose not to report any local tales of a man whose works played such an important part in the curriculum."[21]

Some sources (Bu-ston and the other Tibetan historians) claim that in his later years, Nāgārjuna lived on the mountain of Śrīparvata near the city that would later be called Nāgārjunakoṇḍa ("Hill of Nāgārjuna").[22][23] The ruins of Nāgārjunakoṇḍa are located in Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh. The Caitika and Bahuśrutīya nikāyas are known to have had monasteries in Nāgārjunakoṇḍa.[22] The archaeological finds at Nāgārjunakoṇḍa have not resulted in any evidence that the site was associated with Nagarjuna. The name "Nāgārjunakoṇḍa" dates from the medieval period, and the 3rd-4th century inscriptions found at the site make it clear that it was known as "Vijayapuri" in the ancient period.[24]

Other Nāgārjunas

There are a multitude of texts attributed to "Nāgārjuna", many of these texts date from much later periods. This has caused much confusion for the traditional Buddhist biographers and doxographers. Modern scholars are divided on how to classify these later texts and how many later writers called "Nāgārjuna" existed (the name remains still popular today in Andhra Pradesh).[25]

Some scholars have posited that there was a separate aryuvedic writer called Nāgārjuna which wrote numerous treatises on rasayana. Also, there is a later Tantric Buddhist author by the same name who may have been a scholar at Nālandā University and wrote on Buddhist tantra.[26][25]

There is also a Jain figure of the same name who was said to have traveled to the Himalayas. Walser thinks that it is possible that stories related to this figure influenced Buddhist legends as well.[25]

Works

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

There exist a number of influential texts attributed to Nāgārjuna; however, as there are many pseudepigrapha attributed to him, lively controversy exists over which are his authentic works.

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā

The Mūlamadhyamakakārikā is Nāgārjuna's best-known work. It is "not only a grand commentary on the Buddha's discourse to Kaccayana,[27] the only discourse cited by name, but also a detailed and careful analysis of most of the important discourses included in the Nikayas and the Agamas, especially those of the Atthakavagga of the Sutta-nipata.[28]

Utilizing the Buddha's theory of "dependent arising" (pratitya-samutpada), Nagarjuna demonstrated the futility of [...] metaphysical speculations. His method of dealing with such metaphysics is referred to as "middle way" (madhyama pratipad). It is the middle way that avoided the substantialism of the Sarvastivadins as well as the nominalism of the Sautrantikas.[29]

In the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, "[A]ll experienced phenomena are empty (sunya). This did not mean that they are not experienced and, therefore, non-existent; only that they are devoid of a permanent and eternal substance (svabhava) because, like a dream, they are mere projections of human consciousness. Since these imaginary fictions are experienced, they are not mere names (prajnapti)."[29]

Major attributed works

According to David Seyfort Ruegg, the Madhyamakasastrastuti attributed to Candrakirti (c. 600 – c. 650) refers to eight texts by Nagarjuna:

the (Madhyamaka)karikas, the Yuktisastika, the Sunyatasaptati, the Vigrahavyavartani, the Vidala (i.e. Vaidalyasutra/Vaidalyaprakarana), the Ratnavali, the Sutrasamuccaya, and Samstutis (Hymns). This list covers not only much less than the grand total of works ascribed to Nagarjuna in the Chinese and Tibetan collections, but it does not even include all such works that Candrakirti has himself cited in his writings.[30]

According to one view, that of Christian Lindtner, the works definitely written by Nāgārjuna are:[31]

- Mūlamadhyamaka-kārikā (Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way), available in three Sanskrit manuscripts and numerous translations.[32]

- Śūnyatāsaptati (Seventy Verses on Emptiness), accompanied by a prose commentary ascribed to Nagarjuna himself.

- Vigrahavyāvartanī (The End of Disputes)

- Vaidalyaprakaraṇa (Pulverizing the Categories), a prose work critiquing the categories used by Indian Nyaya philosophy.

- Vyavahārasiddhi (Proof of Convention)

- Yuktiṣāṣṭika (Sixty Verses on Reasoning)

- Catuḥstava (Four Hymns): Lokātīta-stava (Hymn to transcendence), Niraupamya-stava (to the Peerless), Acintya-stava (to the Inconceivable), and Paramārtha-stava (to Ultimate Truth).[33]

- Ratnāvalī (Precious Garland), subtitled (rajaparikatha), a discourse addressed to an Indian king (possibly a Satavahana monarch).[34]

- Pratītyasamutpādahṝdayakārika (Verses on the heart of Dependent Arising), along with a short commentary (Vyākhyāna).

- Sūtrasamuccaya, an anthology of various sutra passages.

- Bodhicittavivaraṇa (Exposition of the awakening mind)

- Suhṛllekha (Letter to a Good Friend)

- Bodhisaṃbhāraśāstra (Requisites of awakening), a work the path of the Bodhisattva and paramitas, it is quoted by Candrakirti in his commentary on Aryadeva's four hundred. Now only extant in Chinese translation (Taisho 1660).[35]

The Tibetan historian Buston considers the first six to be the main treatises of Nāgārjuna (this is called the "yukti corpus", rigs chogs), while according to Tāranātha only the first five are the works of Nāgārjuna. TRV Murti considers Ratnaavali, Pratitya Samutpaada Hridaya and Sutra Samuccaya to be works of Nāgārjuna as the first two are quoted profusely by Chandrakirti and the third by Shantideva.[36]

Other attributed works

In addition to works mentioned above, several others are attributed to Nāgārjuna. There is an ongoing, lively controversy over which of those works are authentic. Contemporary research suggest that some these works belong to a significantly later period, either to late 8th or early 9th century CE, and hence can not be authentic works of Nāgārjuna. Several works considered important in esoteric Buddhism are attributed to Nāgārjuna and his disciples by traditional historians like Tāranātha from 17th century Tibet. These historians try to account for chronological difficulties with various theories. For example, apropagation of later writings via mystical revelation. For a useful summary of this tradition, see Wedemeyer 2007.

According to Ruegg, "three collections of stanzas on the virtues of intelligence and moral conduct ascribed to Nagarjuna are extant in Tibetan translation": Prajñasatakaprakarana, Nitisastra-Jantuposanabindu and Niti-sastra-Prajñadanda.[37]

Other works are extant only in Chinese, one of these is the Shih-erh-men-lun or 'Twelve-topic treatise' (*Dvadasanikaya or *Dvadasamukha-sastra); one of the three basic treatises of the Sanlun school (East Asian Madhyamaka).[38]

Lindtner considers that the Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa (Ta-chih-tu-lun, Taisho 1509, "Commentary on the great prajñaparamita") which has been influential in Chinese Buddhism, is not a genuine work of Nāgārjuna. This work is also only attested in a Chinese translation by Kumārajīva and is unknown in the Tibetan and Indian traditions.[39] There is much discussion as to whether this is a work of Nāgārjuna, or someone else. Étienne Lamotte, who translated one third of the work into French, felt that it was the work of a North Indian bhikṣu of the Sarvāstivāda school who later became a convert to the Mahayana. The Chinese scholar-monk Yin Shun felt that it was the work of a South Indian and that Nāgārjuna was quite possibly the author. These two views are not necessarily in opposition and a South Indian Nāgārjuna could well have studied the northern Sarvāstivāda. Neither of the two felt that it was composed by Kumārajīva, which others have suggested.

Other attributed works include:[40]

- Bhavasamkranti

- Dharmadhatustava (Hymn to the Dharmadhatu), uncertain authorship, according to Ruegg, it shows traces of later Mahayana and Tantrik thought.

- Salistambakarikas

- A commentary on the Dashabhumikasutra.

- Mahayanavimsika (uncertain authorship as per Ruegg)

- *Ekaslokasastra (Taisho 1573)

- *Isvarakartrtvanirakrtih (A refutation of God/Isvara)

Philosophy

Comparative philosophy

Hinduism

Nāgārjuna was fully acquainted with the classical Hindu philosophies of Samkhya and even the Vaiseshika.[41] Nāgārjuna assumes a knowledge of the definitions of the sixteen categories as given in the Nyaya Sutras, the chief text of the Hindu Nyaya school, and wrote a treatise on the pramanas where he reduced the syllogism of five members into one of three. In the Vigrahavyavartani Karika, Nāgārjuna criticises the Nyaya theory of pramanas (means of knowledge) [42]

Mahāyānaism

Nāgārjuna was conversant with many of the Śrāvaka philosophies and with the Mahāyāna tradition; however, determining Nāgārjuna's affiliation with a specific nikāya is difficult, considering much of this material has been lost. If the most commonly accepted attribution of texts (that of Christian Lindtner) holds, then he was clearly a Māhayānist, but his philosophy holds assiduously to the Śrāvaka Tripiṭaka, and while he does make explicit references to Mahāyāna texts, he is always careful to stay within the parameters set out by the Śrāvaka canon.

Nāgārjuna may have arrived at his positions from a desire to achieve a consistent exegesis of the Buddha's doctrine as recorded in the āgamas. In the eyes of Nāgārjuna, the Buddha was not merely a forerunner, but the very founder of the Madhyamaka system.[43] David Kalupahana sees Nāgārjuna as a successor to Moggaliputta-Tissa in being a champion of the middle-way and a reviver of the original philosophical ideals of the Buddha.[44]

Pyrrhonism

Because of the high degree of similarity between Nāgārjuna's philosophy and Pyrrhonism, particularly the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus,[45] Thomas McEvilley suspects that Nāgārjuna was influenced by Greek Pyrrhonist texts imported into India.[46] Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360-c. 270 BCE), the founder of this school of sceptical philosophy, was himself influenced by Indian philosophy. Pyrrho traveled to India with Alexander the Great's army and studied with the gymnosophists. According to Christopher I. Beckwith, Pyrrho's teachings are based on Buddhism, because the Greek terms adiaphora, astathmēta and anepikrita in the Aristocles Passage resemble the Buddhist three marks of existence.[47] According to him, the key innovative tenets of Pyrrho's scepticism were only found in Indian philosophy at the time and not in Greece.[48]

Philosophical positions

Sunyata

Nāgārjuna's major thematic focus is the concept of śūnyatā (translated into English as "emptiness") which brings together other key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anātman "not-self" and pratītyasamutpāda "dependent origination", to refute the metaphysics of some of his contemporaries. For Nāgārjuna, as for the Buddha in the early texts, it is not merely sentient beings that are "selfless" or non-substantial; all phenomena (dhammas) are without any svabhāva, literally "own-being", "self-nature", or "inherent existence" and thus without any underlying essence. They are empty of being independently existent; thus the heterodox theories of svabhāva circulating at the time were refuted on the basis of the doctrines of early Buddhism. This is so because all things arise always dependently: not by their own power, but by depending on conditions leading to their coming into existence, as opposed to being.

Nāgārjuna means by real any entity which has a nature of its own (svabhāva), which is not produced by causes (akrtaka), which is not dependent on anything else (paratra nirapeksha).[49]

Chapter 24 verse 14 of the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā provides one of Nāgārjuna's most famous quotations on emptiness and co-arising:[50]

sarvaṃ ca yujyate tasya śūnyatā yasya yujyate

sarvaṃ na yujyate tasya śūnyaṃ yasya na yujyate

All is possible when emptiness is possible.

Nothing is possible when emptiness is impossible.

As part of his analysis of the emptiness of phenomena in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, Nāgārjuna critiques svabhāva in several different concepts. He discusses the problems of positing any sort of inherent essence to causation, movement, change and personal identity. Nāgārjuna makes use of the Indian logical tool of the tetralemma to attack any essentialist conceptions. Nāgārjuna's logical analysis is based on four basic propositions:

- All things (dharma) exist: affirmation of being, negation of non-being

- All things (dharma) do not exist: affirmation of non-being, negation of being

- All things (dharma) both exist and do not exist: both affirmation and negation

- All things (dharma) neither exist nor do not exist: neither affirmation nor negation [51]

To say that all things are 'empty' is to deny any kind of ontological foundation; therefore Nāgārjuna's view is often seen as a kind of ontological anti-foundationalism[52] or a metaphysical anti-realism.[53]

Understanding the nature of the emptiness of phenomena is simply a means to an end, which is nirvana. Thus Nāgārjuna's philosophical project is ultimately a soteriological one meant to correct our everyday cognitive processes which mistakenly posits svabhāva on the flow of experience.

Some scholars such as Fyodor Shcherbatskoy and T.R.V. Murti held that Nāgārjuna was the inventor of the Shunyata doctrine; however, more recent work by scholars such as Choong Mun-keat, Yin Shun and Dhammajothi Thero has argued that Nāgārjuna was not an innovator by putting forth this theory,[54][55][56] but that, in the words of Shi Huifeng, "the connection between emptiness and dependent origination is not an innovation or creation of Nāgārjuna".[57]

Two truths

Nāgārjuna was also instrumental in the development of the two truths doctrine, which claims that there are two levels of truth in Buddhist teaching, the ultimate truth (paramārtha satya) and the conventional or superficial truth (saṃvṛtisatya). The ultimate truth to Nāgārjuna is the truth that everything is empty of essence,[58] this includes emptiness itself ('the emptiness of emptiness'). While some (Murti, 1955) have interpreted this by positing Nāgārjuna as a neo-Kantian and thus making ultimate truth a metaphysical noumenon or an "ineffable ultimate that transcends the capacities of discursive reason",[59] others such as Mark Siderits and Jay L. Garfield have argued that Nāgārjuna's view is that "the ultimate truth is that there is no ultimate truth" (Siderits) and that Nāgārjuna is a "semantic anti-dualist" who posits that there are only conventional truths.[59] Hence according to Garfield:

Suppose that we take a conventional entity, such as a table. We analyze it to demonstrate its emptiness, finding that there is no table apart from its parts […]. So we conclude that it is empty. But now let us analyze that emptiness […]. What do we find? Nothing at all but the table’s lack of inherent existence. […]. To see the table as empty […] is to see the table as conventional, as dependent.[60]

In articulating this notion in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, Nāgārjuna drew on an early source in the Kaccānagotta Sutta,[61] which distinguishes definitive meaning (nītārtha) from interpretable meaning (neyārtha):

By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one reads the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "non-existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one reads the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one.

By and large, Kaccayana, this world is in bondage to attachments, clingings (sustenances), and biases. But one such as this does not get involved with or cling to these attachments, clingings, fixations of awareness, biases, or obsessions; nor is he resolved on "my self". He has no uncertainty or doubt that just stress, when arising, is arising; stress, when passing away, is passing away. In this, his knowledge is independent of others. It's to this extent, Kaccayana, that there is right view.

"Everything exists": That is one extreme. "Everything doesn't exist": That is a second extreme. Avoiding these two extremes, the Tathagata teaches the Dhamma via the middle...[62]

The version linked to is the one found in the nikayas, and is slightly different from the one found in the Samyuktagama. Both contain the concept of teaching via the middle between the extremes of existence and non-existence.[63][64] Nagarjuna does not make reference to "everything" when he quotes the agamic text in his Mūlamadhyamakakārikā.[65]

Causality

Jay L. Garfield describes that Nāgārjuna approached causality from the four noble truths and dependent origination. Nāgārjuna distinguished two dependent origination views in a causal process, that which causes effects and that which causes conditions. This is predicated in the two truth doctrine, as conventional truth and ultimate truth held together, in which both are empty in existence. The distinction between effects and conditions is controversial. In Nāgārjuna's approach, cause means an event or state that has power to bring an effect. Conditions, refer to proliferating causes that bring a further event, state or process; without a metaphysical commitment to an occult connection between explaining and explanans. He argues nonexistent causes and various existing conditions. The argument draws from unreal causal power. Things conventional exist and are ultimately nonexistent to rest in the middle way in both causal existence and nonexistence as casual emptiness within the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā doctrine. Although seeming strange to Westerners, this is seen as an attack on a reified view of causality.[66]

Relativity

Nāgārjuna also taught the idea of relativity; in the Ratnāvalī, he gives the example that shortness exists only in relation to the idea of length. The determination of a thing or object is only possible in relation to other things or objects, especially by way of contrast. He held that the relationship between the ideas of "short" and "long" is not due to intrinsic nature (svabhāva). This idea is also found in the Pali Nikāyas and Chinese Āgamas, in which the idea of relativity is expressed similarly: "That which is the element of light ... is seen to exist on account of [in relation to] darkness; that which is the element of good is seen to exist on account of bad; that which is the element of space is seen to exist on account of form."[67]

Action

Nagarjuna stated that action itself was the fundamental aspect of the universe. To him, human beings were not creatures with the ability to act. Rather, action itself manifested as human beings and as the entire universe.[68]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Kalupahana, David. A History of Buddhist Philosophy. 1992. p. 160.

- ^ a b Garfield, Jay L. (1995), The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Westerhoff (2009), p. 4.

- ^ Walser (2005) p. 3.

- ^ Garfield (1995), p. 87.

- ^ Walser (2005), p. 43.

- ^ Mäll, Linnart. Studies in the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā and other essays. 2005. p. 96

- ^ a b Walser (2005), p. 60.

- ^ a b c Walser (2005), p. 61.

- ^ a b Kalupahana, David. A History of Buddhist Philosophy. 1992. p. 160

- ^ a b c Walser (2005), p. 66.

- ^ Walser (2005), p. 87.

- ^ "Notes on the Nagarjunikonda Inscriptions", Dutt, Nalinaksha. The Indian Historical Quarterly 7:3 1931.09 pp. 633–53 "..Tibetan tradition which says that Nāgārjuna was born of a brahmin family of Vidarbha."

- ^ Geri Hockfield Malandra, Unfolding A Mandala: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Ellora, SUNY Press, 1993, p. 17

- ^ Shōhei Ichimura, Buddhist Critical Spirituality: Prajñā and Śūnyatā, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (2001), p. 67

- ^ Bkra-śis-rnam-rgyal (Dwags-po Paṇ-chen), Takpo Tashi Namgyal, Mahamudra: The Quintessence of Mind and Meditation, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (1993), p. 443

- ^ Walser (2005), pp. 69, 74.

- ^ Walser (2005), p. 74.

- ^ Berger, Douglas. "Nagarjuna (c. 150—c. 250)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Walser (2005), pp. 75-76.

- ^ Walser (2005), p. 78

- ^ a b Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. 2007. p. 242

- ^ Walser (2005), p. 72.

- ^ K. Krishna Murthy (1977). Nāgārjunakoṇḍā: A Cultural Study. Concept Publishing Company. p. 1. OCLC 4541213.

- ^ a b c Walser (2005), p. 69.

- ^ Hsing Yun, Xingyun, Tom Manzo, Shujan Cheng Infinite Compassion, Endless Wisdom: The Practice of the Bodhisattva Path Buddha's Light Publishing Hacienda Heights California

- ^ See SN 12.15 Kaccayanagotta Sutta: To Kaccayana Gotta (on Right View) Archived 29 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kalupahana 1994, p. 161.

- ^ a b Kalupahana 1992, p. 120.

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 8.

- ^ Lindtner, C. (1982). Nagarjuniana: studies in the writings and philosophy of Nāgārjuna, Copenhagen: Akademisk forlag, p. 11.

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 9.

- ^ Fernando Tola & Carmen Dragonetti, Nagarjuna's Catustava, Journal of Indian Philosophy 13 (1):1-54 (1985)

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 24.

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 29.

- ^ TRV Murti, Central philosophy of Buddhism, pp. 89–91

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 27.

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 28.

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, p. 32.

- ^ Ruegg, David Seyfort, ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1981, pp. 28-46.

- ^ TRV Murti, The central philosophy of Buddhism, p. 92

- ^ S.Radhakrishnan, Indian Philosophy Volume 1, p. 644

- ^ Christian Lindtner, Master of Wisdom. Dharma Publishing 1997, p. 324.

- ^ David Kalupahana, Mulamadhyamakakarika of Nāgārjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. Motilal Banarsidass, 2005, pp. 2, 5.

- ^ Adrian Kuzminski, Pyrrhonism: How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism 2008

- ^ Thomas McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought 2002 pp 499-505

- ^ Beckwith 2015, p. 28.

- ^ Beckwith 2015, p. 221.

- ^ S.Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy Volume 1, p. 607

- ^ Siderits, Mark; Katsura, Shoryu (2013). Nagarjuna's Middle Way: Mulamadhyamakakarika (Classics of Indian Buddhism). Wisdom Publications. pp. 175–76. ISBN 978-1-61429-050-6.

- ^ Dumoulin, Heinrich (1998) Zen Buddhism: a history, India and China, Macmillan Publishing, 43

- ^ Westerhoff, Jan. Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction.

- ^ Siderits, Mark. Nagarjuna as anti-realist, Journal of Indian Philosophy December 1988, Volume 16, Issue 4, pp 311-325.

- ^ Yìn Shùn, An Investigation into Emptiness (Kōng zhī Tànjìu 空之探究) (1985)

- ^ Choong, The Notion of Emptiness in Early Buddhism (1999)

- ^ Medawachchiye Dhammajothi Thero, The Concept of Emptiness in Pali Literature

- ^ Shi huifeng: “Dependent Origination = Emptiness”—Nāgārjuna’s Innovation?

- ^ Garfield, Jay. Empty Words: Buddhist Philosophy and Cross-cultural Interpretation, p. 91.

- ^ a b Siderits, Mark, On the Soteriological Significance of Emptiness, Contemporary Buddhism, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2003.

- ^ Garfield, J. L. (2002). Empty words, pp. 38–39

- ^ Kalupahana, David J. (1986). Nāgārjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. State University of New York Press.

- ^ Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997). SN 12.15 Kaccayanagotta Sutta: To Kaccayana Gotta (on Right View)

- ^ A.K. Warder, A Course in Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1998, pp. 55–56

- ^ For the full text of both versions with analysis see pp. 192–95 of Choong Mun-keat, The Fundamental Teachings of Early Buddhism: A comparative study basted on the Sutranga portion of the Pali Samyutta-Nikaya and the Chinese Samyuktagama; Harrassowitz Verlag, Weisbaden, 2000.

- ^ David Kalupahana, Nagarjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. SUNY Press, 1986, p. 232.

- ^ Garfield, Jay L (April 1994). "Dependent Arising and the Emptiness of Emptiness: Why Did Nāgārjuna Start with Causation?". Philosophy East and West. 44 (2): 219–50. doi:10.2307/1399593. JSTOR 1399593.

- ^ David Kalupahana, Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. The University Press of Hawaii, 1975, pp. 96–97. In the Nikayas the quote is found at SN 2.150.

- ^ Warner, Brad (31 August 2010). Sex, Sin, and Zen: Buddhist Exploration of Sex from Celibacy to Polyamory and Everything in Between. New World Library. ISBN 978-1-57731-910-8.

Sources

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia (PDF). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400866328.

- Garfield, Jay L. (1995), The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Garfield, Jay L. and Graham Priest (2003), “Nāgārjuna and the Limits of Thought”, Philosophy East and West 53 (January 2003): 1-21.

- Jones, Richard H. (2014), Nagarjuna: Buddhism's Most Important Philosopher, 2nd ed. New York: Jackson Square Books.

- Kalupahana, David J. (1986), The Philosophy of the Middle Way. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Kalupahana, David J. (1992), The Principles of Buddhist Psychology, Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications

- Kalupahana, David J. (1994), A history of Buddhist philosophy, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Lamotte, E., Le Traite de la Grande Vertu de Sagesse, Vol I (1944), Vol II (1949), Vol III (1970), Vol IV (1976), Institut Orientaliste: Louvain-la-Neuve.

- Mabbett, Ian, (1998), “The problem of the historical Nagarjuna revisited”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 118(3): 332–46.

- Murti, T. R. V. (1955), The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. George Allen and Unwin, London. 2nd edition: 1960.

- Murty, K. Satchidananda (1971), Nagarjuna. National Book Trust, New Delhi. 2nd edition: 1978.

- Ramanan, K. Venkata (1966), Nāgārjuna's Philosophy. Charles E. Tuttle, Vermont and Tokyo. Reprint: Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi. 1978.

- Ruegg, D. Seyfort (1981), The literature of the Madhyamaka school of philosophy in India (A History of Indian literature), Harrassowitz, ISBN 978-3-447-02204-0.

- Sastri, H. Chatterjee, ed. (1977), The Philosophy of Nāgārjuna as contained in the Ratnāvalī. Part I [ Containing the text and introduction only ]. Saraswat Library, Calcutta.

- Streng, Frederick J. (1967), Emptiness: A Study in Religious Meaning. Nashville: Abingdon Press.

- Tuck, Andrew P. (1990), Comparative Philosophy and the Philosophy of Scholarship: on the Western Interpretation of Nāgārjuna, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walser, Joseph (2002), Nagarjuna And The Ratnavali: New Ways To Date An Old Philosopher, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 25 (1-2), 209-262

- Walser, Joseph (2005), Nāgārjuna in Context: Mahāyāna Buddhism and Early Indian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Westerhoff, Jan (2010), The Dispeller of Disputes: Nāgārjuna's Vigrahavyāvartanī. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Westerhoff, Jan (2009), Nāgārjuna's Madhyamaka. A Philosophical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wedemeyer, Christian K. (2007), Āryadeva's Lamp that Integrates the Practices: The Gradual Path of Vajrayāna Buddhism according to the Esoteric Community Noble Tradition. New York: AIBS/Columbia University Press.

External links

- A Reader Guide to the Works of Nagarjuna from Shambhala Publications

- Westerhoff, Jan Christoph. "Nāgārjuna". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Rhys Davids, T. W. (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 151.

- "Nagarjuna". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Nāgārjuna - Sanskrit Buddhist texts: Acintyastava, Bodhicittavivaraṇa, Ratnāvalī, Mūlamadhyamakakārikās &c.

- Overview of traditional biographical accounts

- Online version of the Ratnāvalī (Precious Garland) in English Translated by Prof. Vidyakaraprabha and Bel-dzek

- Online version of the Suhṛllekha (Letter to a Friend) in English Translated by Alexander Berzin

- Works by or about Nagarjuna at the Internet Archive

- Works by Nagarjuna at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Nārāgjuna vis-à-vis the Āgama-s and Nikāya-s Byoma Kusuma Nepalese Dharmasangha

- ZenEssays: Nagarjuna and the Madhyamika

- Mula madhyamaka karika online Tibetan and English version translated by Stephen Batchelor

- 150 births

- 250 deaths

- Mahayana Buddhism writers

- 2nd-century Buddhist monks

- 3rd-century Buddhist monks

- 3rd-century Indian philosophers

- Indian scholars of Buddhism

- People from Guntur district

- Mahayana Buddhists

- 3rd-century Indian writers

- Madhyamaka scholars

- Mahasiddhas

- Ontologists

- Telugu people

- Tibetan Buddhist spiritual teachers

- Buddhist yogis

- Converts to Buddhism from Hinduism

- Bodhisattvas

- Idealists

- Rangtong

- Monks of Nalanda

- Writers from Andhra Pradesh

- 2nd-century Indian philosophers

- Scholars from Andhra Pradesh

- 2nd-century Indian writers

- Indian male writers

- Indian male philosophers

- Indian Buddhist monks

- Pyrrhonism

- Founders of Buddhist sects

- Sanron-shū

- Jōdo Shin patriarchs