NHS targets

NHS targets are performance measures used by NHS England, NHS Scotland, NHS Wales, and the Health and Social Care service in Northern Ireland. These vary by country but assess the performance of each health service against measures such as 4 hour waiting times in Accident and Emergency departments, weeks to receive an appointment and/or treatment, and performance in specific departments such as oncology.

History

[edit]The Major Conservative government first set public targets for the NHS in the 1990s – for example, guaranteeing a maximum two-year wait for non-emergency surgery and reducing rates of death from specific diseases.

The subsequent Labour government introduced far more targets and managed performance far more aggressively - a management regime sometimes referred to as 'targets and terror'.[1] Targets were blamed for distorting clinical priorities,[2] and in particular for one organisation achieving a target at the expense of another. For example, ambulances have been forced to queue up outside a busy emergency departments so that the ambulances might not be able to meet their target in responding to emergency calls,[3] but the hospital can meet its A&E target. Excess emphasis on the targets can mean that other important aspects of care, especially those not easily measured, may be neglected.[4] Some have however praised targets for producing faster reductions in waiting times in England than other UK countries between 1996 and 2006.[5]

NHS England under the Conservative governments reduced the number of targets, in particular removing most of those relating to health inequality, and encouraged a system wide approach. However shortage of staff and funding meant that performance against targets nonetheless declined.[6] Guidance published in February 2018 conceded that most of the targets would not be met before April 2019.[7] The hospital care and A&E performance measures for October 2019 were the worst ever recorded.[8]

Sajid Javid called for a ‘proper review of NHS targets’ in September 2021.[9]

According to Jeremy Hunt the Stafford Hospital scandal showed that concentrating on national targets led to managers deprioritising the safety and well-being of patients. Targets can benefit patients but they can also lead to bureaucracy, gaming and poor patient care, or as David Nicholson famously put it - "hitting the target and missing the point". But they are alluring to politicians. Hunt says the effectiveness of targets is in inverse proportion to their quantity and points out that no other country runs its healthcare system by targets. Goodhart's law applies: "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure".[10]

National approaches

[edit]England

[edit]The NHS Constitution for England specifies waiting times in the accompanying Handbook, but does not provide a remedy should they be breached. Non-acute crisis response waiting time targets are to be introduced by NHS England for integrated care systems from April 2022. Performance is to be measured on the percentage of services delivered within two hours. Mental health targets are also planned, although no start date has been set, requiring require that urgent referrals to community crisis services should be seen within 24 hours, and “very urgent” referrals should be seen within four hours. Mental health patients referred from emergency departments should be seen face-to-face by liaison teams within one hour.[11]

Scotland

[edit]The Patient Rights (Scotland) Act 2011 establishes the treatment time guarantee, but also does not specify a remedy should it not be met.[12]

Northern Ireland

[edit]Targets in Northern Ireland are set by the Health and Social Care Board and are less demanding than in the rest of the UK. None have been met since 2015, and some for considerably longer.[13]

Wales

[edit]Targets in Wales are set by the Welsh Government and set out in the NHS Wales Delivery Framework.[14] The Welsh Government has taken a different approach to some areas of care, such as becoming the first nation in the UK to have a single waiting times target for cancer treatment.[15] The Welsh NHS has broadly under-performed compared to the English NHS,[16] with higher waiting times for both urgent and routine care. However a Full Fact report by the Chief Executive of the Nuffield Trust Nigel Edwards acknowledges that the two nations targets are not directly comparable because "the Welsh population is older, sicker and more deprived than the English population—so its NHS has to work harder".[16]

Accident and emergency departments

[edit]

A four-hour target in emergency departments was introduced by the Department of Health for National Health Service acute hospitals in England. The original target was set at 100%, but lowered to reflect clinical concerns that there will always be patients who need to spend slightly longer in A&E, under observation. Setting a target that, by 2004, at least 98% of patients attending an A&E department must be seen, treated, and admitted or discharged in under four hours.[17] The target was further moved to 95% of patients within four hours in 2010 as a result of the coalition's claims that 98% was not clinically justified.[18] Trusts which failed to meet the target could be fined. In July 2016 NHS trusts were set new "performance improvement trajectories". For 47 of the 140 trusts with "type one" major A&E facilities this meant a target of less than 95% waiting under 4 hours.[19] In January 2017 Jeremy Hunt announced that the target would in future only apply to "urgent health problems".[20] In January 2018 only 77.1% of patients were admitted or discharged within four hours, the worst ever performance for type one A&E departments.[21] In December 2018 it was reported that patients with only minor ailments could be excluded from the target and a new target introduced so the most urgent cases should be seen within an hour.[22]

The effect of the target can be that patients waiting just below 4 hours get a lot of attention, but once the target is breached there is no further consequence. The average time spent by a patient in A&E who has breached four hours is around eight hours.[23]

In January 2022 research published in the Emergency Medicine Journal found that there was one extra death For every 82 admitted patients whose time to inpatient bed transfer is delayed more than 6 to 8 hours from time of arrival at the emergency department.[24]

New standards

[edit]In May 2021, after prolonged consultation NHS England announced that the 4 hour target was to be replaced by a new set of 10 metrics. The new “bundle of ten standards” includes

- Response times for ambulances

- Reducing avoidable trips (conveyance rates) to emergency departments by 999 ambulances

- Proportion of contacts via NHS 111 that receive clinical input

- Percentage of ambulance handovers (from ambulance to A&E) within 15 minutes

- Time to initial assessment — percentage within 15 minutes

- Average time in department — for non-admitted patients

- Average time in department — for admitted patients

- Clinically ready to proceed (time from when decision is made to admit or discharge, and patient is admitted or discharged)

- Patients spending more than 12 hours in A&E

- Critical time standards — aimed at ensuring the highest priority patients get care within a set timeframe such as an hour[25]

In September 2022 Thérèse Coffey said: “I can absolutely say there will be no changes to the target for four-hour waits in A&E.”[26]

Objective

[edit]The Labour government (1997-2010) had identified a requirement to promote improvements in A&E departments, which had suffered under-funding for a number of years. The target, accompanied by extra financial support, was a key plan to achieve the improvements. Prime Minister Blair felt the targets had been successful in achieving their aim. "We feel, and maybe we are wrong, that one way we've managed to do that promote improvements in A&E is by setting a clear target".[27]

48% of departments said they did not meet the target for the period ending 31 December 2004.[28] Government figures show that in 2005–06, 98.2% of patients were seen, diagnosed and treated within four hours of their arrival at A&E, the first full financial year in which this has happened.[29]

The four-hour target triggered the introduction of the acute assessment unit (also known as the medical assessment unit), which works alongside the emergency department but is outside it for statistical purposes in the bed management cycle. It is claimed that though A&E targets have resulted in significant improvements in completion times, the current target would not have been possible without some form of patient re-designation or re-labelling taking place, so true improvements are somewhat less than headline figures might suggest and it is doubtful that a single target (fitting all A&E and related services) is sustainable.[30]

Although the four-hour target helped to bring down waiting times when it was first introduced, since September 2012 (after the introduction of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and top-down reorganisation of the NHS) hospitals in England struggled to stick to it, prompting suggestions that A&E departments may be reaching a limit in terms of what can be achieved within the available resources.[31] The announcement of the reduction of the target from 98% to 95% was immediately followed by a reduction in attainment to the lower level.[32]

Performance

[edit]

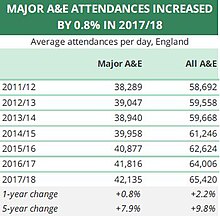

By December 2014, the number of patients being treated within four hours had fallen to 91.8%.[33] From December 2015, the 95% target over England as a whole was missed every month. From October–December 2016, only 4 out of 139 hospitals with major type 1 A&E departments met the target.[34] In November 2018, the British Medical Association reported that performance on emergency admissions, trolley waits for more than four hours and A&E patients seen within four hours in the summer of 2017 was worse than in the winters of 2011–15.[35] Performance against the four-hour wait target in the summer of 2018 was the worst second quarter performance recorded. Only 88.9% of patients were seen within four hours in September. The number of people admitted, transferred or discharged within four hours in emergency departments in September was up more than 3% compared to September 2017 with a 7% rise in emergency admissions said by John Appleby to be astonishing.[36] Attendance at A&E departments has been increasingly steadily for many years, more so at ‘type 3’ departments, like urgent care centres (where waiting times are generally lower). In the first eight months of 2018, an average of 67,000 people attended each day.[37] In January 2019, only 84.4% of patients were seen within four hours, the worst figure since the target was introduced in 2004.[38] In November 2019 not a single A&E department hit the four-hour wait time target.[39]

Performance in the first three months of 2019-20 was the worst since records began in 2011.[40]

National A&E performance

[edit]Scotland

[edit]In Scotland, the target is for 95% of A&E patients to be either admitted, transferred or discharged in four hours. It was last met in July 2017.[41] Scotland has performed best on this measure out of the four UK nations, a position it has held since September 2015.[42] However like all other UK nations this performance has recently declined.[42] In Scotland this target has dropped 5% between May 2018 and September 2019.[42]

England

[edit]In England, the target is also for 95% of A&E patients to be treated, transferred, and discharged within four hours. However performance has fluctuated between 90 and 84% between 2015 and 2019,[42] consistently putting it second in the United Kingdom.[42] However performance against the target declined almost 10% between May 2018 and September 2019.[42]

In March 2022 average waits for an ambulance for stroke and heart attack patients (category 2) reached as long as two hours in some regions. The national target for reaching them is 18 minutes. According to the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives more than 3,000 patients may have suffered “severe harm” from ambulance delays in February 2022.[43] In June 2022 ambulance response times for the most serious category one incidents, including cardiac arrests, sank to an average of 9 minutes and 6 seconds, half a minute slower than in May. The target time is 7 minutes.[44] Maria Caulfield told the House of Commons on 10 July 2022 that ambulance service response time performance had improved month on month, but in fact it had deteriorated in June.[45]

Wales

[edit]In Wales, the target is also for 95% of A&E patients to be treated, transferred, and discharged within four hours.[42] While higher than the performance in Northern Ireland (60%),[42] the Welsh NHS is third in the United Kingdom, putting it 7 percent behind NHS England and 8% behind NHS Scotland.[42] The Nuffield Trust have identified Welsh underperformance as influenced by the Welsh population being older, sicker and having more deprivation than any other UK nation.[46] Performance against the target has like all other UK nations in recent years, having declined by 7.5% between May 2018 and September 2019.[42]

Northern Ireland

[edit]Targets in Northern Ireland are set by the Health and Social Care Board and are less demanding than in the rest of the UK. None have been met since 2015, and some for considerably longer.[47] A&E waits when considered using the NHS measure of 4 hours to discharge show that performance in Northern Ireland has dropped 13% between May 2018 and September 2019.[42]

Missing the target

[edit]According to the BMA[28] the main reasons for not reaching this target are:

- Not enough inpatient beds

- Delayed discharges

- Delay in accessing specialist opinion

- Not enough nurses

- Not enough middle grade doctors

- Department too small

- Delay in accessing diagnostic services

In 2014, research conducted by QualityWatch, a joint programme from the Nuffield Trust and the Health Foundation, tracked 41 million visits to A&E departments in England in order to better understand the pressures leading to increased waiting times and breaches of the four-hour target. Researchers identified a rise in older patients and related increase in long-term conditions as key factors, alongside extremes of temperature (in both summer and winter) and crowding at peak times. They noted that the majority of pressure was falling on major A&E units, and proposed that rising demand as a result of ageing and population growth may be pushing already stretched emergency departments beyond maximum capacity.[48]

In July 2017 the Royal College of Emergency Medicine produced a report saying that the NHS needed at least 5,000 more beds to achieve safe bed occupancy levels and hit the four-hour target.[49]

Pressure

[edit]Even though exceptions are allowed to the targets, concerns have been raised that the target has put pressure on A&E staff to compromise patient care. A significant proportion (90%) of A&E consultants welcomed the four hour target in a study but felt that 98% was too high a target.[27]

Twelve hour target

[edit]England

[edit]At the same time as the four target was introduced a target that no patient should wait longer than 12 hours before they are admitted to a ward, if that is required, was introduced. In England time was measured from the point a decision to admit is made and not from the moment the patient arrives. Between January and March 2012 only 15 patients in England waited more than 12 hours, but in the same months in 2017 1,597 patients breached the target.[50] In January 2018 1,043 patients waited over 12 hours for a bed, the worst figure ever recorded. 272 were at University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust.[21] Problems at Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust led to more than 1,000 cases of patients waiting over 12 hours for admission in 2018–19. This was about a third of all the 12 hour breaches, which were mostly mental health cases - where admission to a ward is not within the control of the trust running the A&E department. A review found that some patients in Lancashire were “potentially being held against their will without appropriate legal provision”. Some were detained in seclusion rooms for more than a week under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983, which only provides that patients can be lawfully detained for 24 hours, with a possible 12-hour extension.[51] In December 2019 trusts in London were told to set up dedicated spaces to care for three mental health patients in every A&E department.[52]

In December 2019 there were 2,347 breaches, compared with 284 recorded in December 2018.[53] In February 2022 there were 16,404 breaches and in March 2022 22,506.[54] The NHS Standard Contract for 2022-23 requires hospitals to count 12-hour waits from time of patients’ arrival in the Emergency Department to the time they are admitted to a ward.[55] Measured in this way February and March 2022 show around one in five admissions through ED waited more than 12 hours from arriving until being admitted to a ward – equating to around 158,000 cases, 22% of attendances.[56] Problems were particularly severe for people with mental health problems, with many examples of mental health patients waiting up to three days in emergency departments for a mental health inpatient bed to become available.[57] When time was measured from time of arrival in the department to admission to a ward the figures of people waiting more than 12 hours were about six times greater than the nationally published figures[58] which in July reached 29,317.[59]

Wales

[edit]The Welsh NHS sets a measure of patients waiting more than 12 hours to be treated, transferred, and discharged by A&E. In January 2019, the Welsh NHS has recorded a record 6,882 patients waiting more than 12 hours in A&E, and Morriston Hospital in Swansea represented 15% of all A&E patients waiting more than 12 hours.[42] The Welsh NHS Confederation responded to the figure by stating its disappointment but acknowledging numbers of patients attending with complex needs were increasing in Wales.[42] Ambulance response times however improved and hit their target for the first time since October.[42]

Cancer

[edit]All across the UK the target is that patients should be treated within 62 days of an urgent referral, but the way this is measured varies.[60] In Northern Ireland the target has not been met since 2015.[13]

The Welsh Government in 2019 became the first nation in the UK to have a single waiting times target for cancer treatment.[15]

In England 93% of patients referred for investigation of breast symptoms, even if cancer is not initially suspected, should be seen by a specialist within two weeks.[61] Only 77.5% of patients referred for breast symptoms between April and June 2019 were seen within 2 weeks.[62]

Only 38% of hospitals met the target in 2019 and 22.5% of people waited longer than two months for their first treatment.[63] In February 2022 10.7% of patients treated waited more than 104 days.[64]

Planned treatment

[edit]Over four million patients were waiting for non urgent hospital care as of July 2017. The Royal College of Surgeons together with other medical groups fear patients are waiting longer in anxiety and pain for hospital procedures.[65] The target was that 90% of patients admitted to hospital for treatment and 95% of those not admitted should receive consultant-led care within 18 weeks unless it is clinically appropriate not to do so, or they choose to wait. The proportion of people waiting more than the six week target for diagnostic tests was at its highest since records began in September 2018.[36] By August 2019 less than 49% of hospital services were achieving the target and across England the average wait was around 23 weeks.[66] The clinical commissioning group joint committee for mid and south Essex in December 2019 reported that local hospitals were “now working” to a 40-week referral to treatment target.[67]

One year wait

[edit]In December 2017 there were 1,750 patients waiting a year or more, the highest total since August 2012. 242 were at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, 156 at Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust and 114 at Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust. 11.8% of those waiting for a procedure had waited 18 weeks or more.[68] By March 2018 there were 2,647. The largest numbers were at Northern Lincolnshire and Goole Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust and East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust.[69] 2,432 patients had waited longer than a year in November 2018. In January 2019 NHS England announced that in future both providers and commissioners would be fined £2,500 for each such patient.[70] In February 2022 299,478 patients had been on the list for over 52 weeks. Of those 23,281 had been waiting more than 2 years.[71]

In Northern Ireland more than a third of patients, 94,222 people, had waited more than a year for their first appointment in October 2018. According to the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland the 52-week target had "not been completely achieved in over 11 years".[72]

In Wales a year target is not measured but a nine month target is monitored. As of January 2020 25,549 patients (5.5%) had been waiting more than nine months to receive treatment.[42]

Six month wait

[edit]England

[edit]445,360 in England had been waiting six months or more by the end of December 2017 - three times more than in 2013. The President of the Royal College of Surgeons said it was “completely shameful” that patients were being forced to resort to paying for operations the NHS should provide as these waiting times led to an increase of 53% between 2012 and 2016 in the numbers paying personally for private operations.[73]

In July 2021 it was reported that there was a 46% increase in patients waiting more than 104 weeks for treatment, from 2,597 to 3,802 from April to May.[74] There were 5.45 million people waiting for hospital treatment in England in JUne 2021 with very large differences in the numbers waiting in different areas, with 25 times more patients waiting for heart operations in Birmingham and Solihull than in West Lancashire.[75]

Wales

[edit]In Wales, as of January 2020 83.5% of patients were waiting less than six months to start hospital treatment. This is the lowest figure since December 2015 and was below the Welsh Government's 95% target.[42]

Cancellations

[edit]Between January and March 2018 25,475 operations were cancelled at the last minute for non-clinical reasons by NHS providers - 20% more than the first quarter of 2017, and the highest number since records began in 1994–95. This was 1.3% of all elective activity - the highest proportion recorded since 2004–05.[76]

Community services

[edit]The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan proposed a two-hour standard for urgent community response services in England. These include prescribing and reviewing medication, access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy, and help with nutrition and hydration. Data has been collected since July 2020 and was first published in June 2022. The 70% two-hour response target was met at an all-England level but there were enormous variations between areas.[77]

Proposals for improvement

[edit]Alternatives to surgery

[edit]Research has been conducted on potential approaches and activities that could reduce waiting lists and free up resources. For example in the case for surgery, invasive (surgical) treatment is not necessary the best option for everyone and might even result in worse outcomes than other treatments.[78]

Each year there are around 60,000 gallstone surgeries performed in England. However this procedures are not without risks and symptoms may remain even after surgery. Instead of surgery another option is to monitor the person (watch and wait) to see if symptoms change and provide painkillers. If symptoms get worse surgery can still be provided but many people might not need it and their quality of life will remain the same as people's who underwent surgery. Offering 'watch and wait' could provide similar results as surgery, avoid surgical risks and free up resources in healthcare.[79][80]

In England, together with Wales and Norther Ireland, around 100,000 people undergo hip replacement surgery. The majority of surgeries are successful but for some the artificial hip becomes infected. In these cases further surgery is necessary to remove and replace the hip. This can be done through a one- or a two-stage surgery. However research shows that when feasible one-stage surgery is as affective as two-stage and even results in less complications and speedier recovery. Opting for one-stage surgery when possible would reduce the number of surgeries yearly.[81][82]

Prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer in British men. Although in some cases (localised prostate cancer) this can be life threatening and require treatment, many will not worsen, cause any issues or reduce life expectancy. Treatment for prostate cancer usually consists of surgery or radiotherapy, both of which can cause serious side effects but reduce the chance of the cancer spreading to other parts of the body. An alternative approach is the active monitoring and regular testing of people with prostate cancer and only resorting to invasive treatment if the cancer seems to progress. This would spare people who would not need surgery from its side effects and reduce the number of surgeries and radiotherapy treatments. However the risk of the cancer spreading is somewhat higher (but still low) without radical treatment.[83]

Acute gut conditions such as diverticular disease, cholelithiasis, appendicitis, abdominal wall hernia and blocked bowel often result in emergency hospital admission. Many of these people undergo emergency surgery, for example there are 50,000 emergency appendectomies each year in the UK. However other non-surgical treatments are also possible or simply having surgery at a later point. These treatments might not be less effective than emergency surgery and for some, for example older people with severe frailty, they might even provide better outcomes.[84]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bevan, Gwyn; Hood, Christopher (16 February 2006). "Have targets improved performance in the English NHS?". BMJ. 332 (7538): 419–422. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7538.419. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1370980. PMID 16484272.

- ^ "Have targets improved NHS performance?". The King's Fund. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Watts, Robert (27 October 2012). "Don't leave patients in ambulances to hit A&E targets, hospitals told". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Have targets improved NHS performance?". Kings Fund. 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Connolly, Sheelah; Bevan, Gwyn; Mays, Nicholas (January 2010). "Funding and performance of healthcare systems in the four countries of the UK before and after devolution: a longitudinal analysis of the four countries, 1996/97, 2002/03 and 2006/07, supplemented by cross-sectional regional analysis of England, 2006/07. Technical Report" (PDF). Nuffield Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Check NHS cancer, A&E and operations targets in your area". BBC News. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "NHS allowed to miss A&E target for another year". Health Service Journal. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Hospital waiting times at worst-ever level". BBC. 14 November 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ "Javid wants review of 'nonsense' NHS targets". Health Service Journal. 12 September 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Hunt, Jeremy (2022). Zero. London: Swift Press. p. 82, 87. ISBN 9781800751224.

- ^ "Community services given first ever waiting time target". Health Service Journal. 22 July 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "The NHS paid for my new French hip". BBC. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Northern Ireland NHS 'simply unable to cope with the demands placed on it': report". Belfast Telegraph. 18 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "NHS Wales Delivery Framework and Reporting Guidance 2019-2020" (PDF). Welsh Government. March 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Mark (27 August 2019). "Wales introduces single waiting times target for cancer patients". walesonline. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Edwards, Nigel; Trust, Chief Executive of the Nuffield (6 February 2015). "Fact or Fiction? The Welsh NHS performs poorly compared to the English NHS". Full Fact. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ The Four Hour Target in Accident and Emergency

- ^ "NHS failed to meet four-hour A&E targets for past two months". 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Third of providers will still miss A&E target in March 2017". Health Service Journal. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Jeremy Hunt ditches four-hour target as A&E crisis deepens". Guardian. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Trolley waits soar to record high". Health Service Journal. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "NHS chiefs look to scrap four-hour A&E maximum wait". Guardian. 2 December 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ "Performance Watch: A sneak preview of a keenly awaited review of A&Es". Health Service Journal. 22 May 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Jones, Simon (18 January 2022). "Association between delays to patient admission from the emergency department and all-cause 30-day mortality". Emergency Medicine Journal. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "NHS England gives green light to drop four-hour A&E target". Health Service Journal. 26 May 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Recovery Watch: Will NHSE ever kill off the four-hour target?". Health Service Journal. 28 September 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ a b BBC NEWS | Health | Target 'putting A&E care at risk'

- ^ a b BMA - BMA survey of accident and emergency waiting times, March 2005

- ^ BBC NEWS | Health | A&E success 'not sustainable'

- ^ Mayhew, Les; Smith, David (December 2006). Using queuing theory to analyse completion times in accident and emergency departments in the light of the Government 4-hour target. Cass Business School. pp. 2, 34. ISBN 978-1-905752-06-5. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Blunt, Ian. "Why are people waiting longer in A&E?". QualityWatch. Nuffield Trust & Health Foundation. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Woodcock, Thomas; Poots, Alan J; Bell, Derek (March 2013). "The impact of changing the 4 h emergency access standard on patient waiting times in emergency departments in England". Emergency Medicine Journal. 30 (3): e22. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201175. PMID 22518060. S2CID 22936540.

- ^ "Indicator: A&E waiting times". QualityWatch. Nuffield Trust & Health Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ "What's going on in A&E? The key questions answered". King's Fund. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "NHS emergency care in crisis all year round". Sky News. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ a b "A&Es miss national objective with record low performance". Health Service Journal. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "NHS Key Statistics: England, October 2018". House of Commons Library. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "A&E waits at worst level for 15 years in England". BBC. 14 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "NHS waiting list hits record high as every A&E in country missed four-hour target". Evening Standard. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ "First quarter A&E performance worst since records began". Health Service Journal. 11 July 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "SNP attacked over year of missed NHS targets". Scottish Express. 29 July 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Longest A&E waiting times hit a new record". BBC News. 20 February 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Ambulance waits hit two hours for heart attacks and strokes". Health Service Journal. 1 April 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Emergency performance slumps again as covid hits". Health Service Journal. 14 July 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Exclusive: Minister misled MPs over ambulance crisis". Health Service Journal. 14 July 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "The challenge of change in the NHS in Wales". The Nuffield Trust. 18 January 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Northern Ireland NHS 'simply unable to cope with the demands placed on it': report". Belfast Telegraph. 18 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Blunt, Ian. "Focus on: A&E attendances". QualityWatch. Nuffield Trust & Health Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ "NHS needs 5,000 more beds, warn leading A&E doctors". Health Service Journal. 7 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "12-hour patient waits in A&E increase by 10,000% in five years". Healthcare Leader. 25 September 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Revealed: Why one county saw a third of all 12-hour A&E breaches". Health Service Journal. 17 May 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "Trusts told to create 'dedicated A&E space' for mental health patients". Health Service Journal. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ "Record collapse in emergency care performance". Health Service Journal. 9 January 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Biggest ever rise in 12-hour waits". Health Service Journal. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Daily Insight: Unto the breach". Health Service Journal. 4 March 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Revealed: Secret stats show A&E crisis four times as bad as official numbers". Health Service Journal. 13 May 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Exclusive: 'Outrageous' long A&E waits for mental health patients increase 150pc". Health Service Journal. 19 July 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Trusts reveal thousands of new 12-hour waits". Health Service Journal. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Summer crisis deepens as trolley waits hit new high". Health Service Journal. 11 August 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Check NHS cancer, A&E, ops and mental health targets in your area". BBC. 13 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Trust hits waiting time target in just 8pc of cases". Health Service Journal. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Pensions crisis and staff shortages trigger record low cancer performance". Health Service Journal. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Cancer patients forced to wait 'unacceptably' long time for NHS treatment". ITV News. 11 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "Long cancer waits at highest rate since pandemic hit". Health Service Journal. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "NHS patients waiting for hospital care top 4m for first time in a decade". The Guardian. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023.

- ^ "Majority of local services are now breaching 18 weeks". Health Service Journal. 12 September 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Region 'working to 40-week target' for treatment". Health Service Journal. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Year-plus elective waiters at highest number since 2012". Health Service Journal. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Year-plus waiters rise 75 per cent". Health Service Journal. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "New fines for leaving patients waiting more than a year". Health Service Journal. 10 January 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ "Trusts with the most two-year elective breaches revealed". Health Service Journal. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Lengthy waiting time figures are 'deeply distressing'". Irish News. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Numbers 'going private' for surgery soaring as NHS rationing deepens". Telegraph. 11 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Two-year waiters for elective care up by half to just under 4,000". Health Service Journal. 9 July 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Huge discrepancy in NHS England waiting times for common procedures". Guardian. 1 September 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Last minute cancelled operations hits highest rate since 2005". Health Service Journal. 10 May 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Huge variation in referrals to flagship 'urgent response' service". Health Service Journal. 21 June 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Is surgery the best option? Research provides alternatives". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 21 November 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_65060.

- ^ "Is surgery the best option? Research provides alternatives". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 21 November 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_65060.

- ^ Gallstones: surgery might not always be needed (Report). National Institute for Health Research. 31 October 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_64805.

- ^ "Is surgery the best option? Research provides alternatives". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 21 November 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_65060.

- ^ One-stage hip revisions are as good as 2-stage surgery to replace infected artificial hips (Report). National Institute for Health Research. 25 April 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_57776.

- ^ "Is surgery the best option? Research provides alternatives". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 21 November 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_65060.

- ^ "Is surgery the best option? Research provides alternatives". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 21 November 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_65060.