Karagöz and Hacivat

| Karagöz | |

|---|---|

Karagöz (left) and Hacivat (right) | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Reference | 180 |

| Region | Anatolia |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2009 (4th session) |

Karagöz (lit. 'Blackeye' in Turkish) and Hacivat (shortened in time from "Hacı İvaz" meaning "İvaz the Pilgrim", and also sometimes written as Hacivad) are the lead characters of the traditional Turkish shadow play, popularized during the Ottoman period and then spread to most nation states of the Ottoman Empire. It is most prominent in Turkey, Syria, Egypt, Greece, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Adjara (autonomous republic of Georgia). In Greece, Karagöz is known by his local name Karagiozis; in Bosnia and Herzegovina, he is known by his local name Karađoz.

Overview

[edit]The central theme of the plays is the contrasting interaction between the two main characters. These are perfect foils of each other: in the Turkish version, Karagöz represents the illiterate but straightforward public, whereas Hacivat belongs to the educated class, speaking Ottoman Turkish and using a poetical and literary language. Although Karagöz is the more popular character with the Turkish peasantry, Hacivat is the one with a level head. Though Karagöz always outmatches Hacivat's superior education with his "native wit," he is also very impulsive and his never-ending deluge of get-rich-quick schemes always results in failure.

Hacivat continually attempts to "domesticate” Karagöz, without much progress. According to the Turkish dramaturge Kırlı, Hacivat emphasizes the upper body with his refined manners and aloof disposition, while Karagöz is more representational of "the lower body with eating, cursing, defecation and the phallus."[1] Other characters in the plays are different ethnic characters living under Ottoman domain such as (in the Turkish version) Armenians, Albanians, Greeks, French, and Arabs, each with their unique, stereotypical traits.

Karagöz–Hacivat plays are especially associated with Ramadan in Turkey, whereas they are associated with the whole year in Greece. Until the rise of radio and film, it was one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Turkey, while in Greece it continues to be popular and televised.

History

[edit]When the plays were first performed is unclear. Some believe that it originates from the island of Java where shadow puppet shows (wayang kulit) were played already as early as in the 11th century and arrived in the Ottoman Empire via traders. The first Karagöz–Hacivat play was performed for Sultan Selim I (reigned 1512–1520) in Egypt after his conquest of the country in 1517, but 17th century writer Evliya Çelebi stated that it had been performed in the Ottoman palace as early as the reign of Bayezid I (reigned 1389–1402). In the 16th century, Ottoman Grand Mufti Muhammad Ebussuud el-İmadi issued a celebrated opinion allowing the performance of Karagöz plays.[2]

According to one Turkish legend, the first performance of karagöz occurred when a lowly commoner visited the sultan. Rather than simply making a complaint, as most commoners did, he put on a short puppet show to tell a tale about the sultan's corrupt officials. The myth states that the sultan was delighted by the performance so much that he appointed the puppeteer as his Grand Vizier and punished the corrupt officials that had inspired the puppeteer's tale. Another story is that the two main characters, Karagöz and Hacivat were actual people. These two legendarily clownish individuals were construction workers on a mosque in Bursa sometime in the mid-14th century. As a result of the slander of others distracted the other workers, slowing down the construction, and the ruler at the time ordered their execution. They were so sorely missed that they were immortalized as the silly puppets that entertained the Ottoman Empire for centuries.[1]

The theatres had an enormous following and would take place in coffee houses and in rich private houses and even performed before the sultan. Every quarter of the city had its own Karagöz.[3] The month of Ramadan saw many performances of Karagöz plays. After a day of fasting, crowds would wander the streets and celebrate, eating, drinking, dancing, watching street performers, and going into the coffeehouses to see Karagöz plays that drew large crowds.[4] Up until Tanzimat, a series of Westernizing reforms in the 19th century, the plays had frequently had an unlimited amount of satirical and obscene license, making many sexual references and political satire. Eventually, however, the puppets began to face repression from Ottoman authorities, up until the founding of the Turkish Republic, when Karagöz had become almost entirely unrecognizable from its original form.[4]

Before the twentieth century, many Karagöz performers were Jews, who had an active presence in popular Ottoman art forms ranging from music to theater.[5]

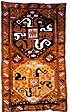

Craft and preparation

[edit]The making and manipulating of the puppets was a very skilled craft where puppeteers had their own guilds. Puppets were made to be about 15 inches or 35–40 centimeters high and oiled to make them look translucent. The puppets were made of either horse, water buffalo or calf skin but the best were made of camel skin (to avoid the puppet being warped and buckle up). They had movable limbs and were jointed with waxed thread at the neck, arms, waist and knees and manipulated from rods in their back and held by the finger of the puppet master. The hide is worked until it is semi-transparent; then it is colored, resulting in colorful projections.[3][1]

The Karagöz theatre consisted of a three sided booth covered with a curtain printed with branches and roses and a white cotton screen by about three feet by four which was inserted in the front. The performance had a three man orchestra who sat at the foot of a small raised stage where they would play for the audience. The show would start when the puppet master lit the oil lamp. The lamp for projection is known as a şem’a (literally "candle"), but is typically an oil lamp. Images are projected onto a white muslin screen known as the ayna ("mirror"). Projections is from the rear, so the audience does not see the puppeteer.

The background and scenery would sometimes include moving ships, riders moving on horseback, swaying palm trees and even dragons. The sound effects included songs and various voices.[3]

Content and structure

[edit]

Karagöz can be deceitful, lewd, and violent, but also include comic scenes with some ribaldry and coarse jokes. Sometimes, women and children would watch from behind curtains and screens, here the jokes would be more sedated.[3][1]

Characters in these plays are the drunkard Tuzsuz Deli Bekir with his wine bottle, the long-necked Uzun Efe, the opium addict Kanbur Tiryaki with his pipe, Altı Kariş Beberuhi (an eccentric dwarf), the half-wit Denyo, the spendthrift Civan, and Nigâr, a flirtatious woman. There may also be dancers and djinns, and various portrayals of non-Turks: an Arab who knows no Turkish (typically a beggar or sweet-seller), a black servant woman, a Circassian servant girl, an Albanian security guard, a Greek (usually a doctor), an Armenian (usually a footman or money-changer), a Jew (usually a goldsmith or scrap-dealer), a Laz (usually a boatman), or an Iranian (who recites poetry with an Azeri accent).[1]

In the Greek version, Hacivat (Hatziavatis) is an educated Greek who works for the Ottoman state, and often represents the Pasha, or simply law and order, whereas Karagöz (Karagiozis) is the shrewd poor peasant Greek, nowadays with Greek-specific attributes of the rayah. The Greek version characters have been altered or altogether introduced: the Pasha, the daughter of the Vezir (both representing the state, the latter being very beautiful and courted unsuccessfully by Karagöz (Karagiozis)), Barba-Giorgos (the rustic Roumeliot shepherd who acts as an uncle to Karagöz), the Morfonios (dandy) with an enormous nose (adapted from a previous Ottoman character), Velingekas (the policeman who represents the Ottoman state following his own macho honor code) as well as innovations such as Stavrakas (the Piraeot Rebet, a tough character) and his Rebetiko band, Nionios from Zante, Manousos the Cretan, Solomon the Jew (adapted from the Ottoman character), Aglaia, wife of Karagöz, his ever hungry three boys Kollitiri, Svouras, and Birikokos, among others.

Karagöz plays are structured in four parts:

- Mukaddime: Introduction. Hacivat sings a semai (different at each performance), recites a prayer, and indicates that he is looking for his friend Karagöz, whom he beckons to the scene with a speech that always ends "Yar bana bir eğlence" ("Oh, for some amusement"). Karagöz enters from the opposite side.

- Muhavere: dialogue between Karagöz and Hacivat

- Fasil: main plot

- Bitiş: Conclusion, always a short argument between Karagöz and Hacivat, always ending with Hacivat yelling at Karagöz that he has "ruined" whatever matter was at hand and has "brought the curtain down," and Karagöz replying "May my transgressions be forgiven."

Entertainers

[edit]

Though Karagöz theatre requires a skilled puppeteer who is capable of controlling the puppets and using different voices, it only requires about four people for a performance that can include dozens of characters. An apprentice, called the sandıkkâr, assists the puppeteer—who is called either the Karagözcü, hayalî (meaning both 'imaginary' and 'image creator') or hayalbaz— by handing him the puppets in the correct order and setting up the theatre before the show. A singer, or yardak, might sing a song in the prelude, but the yardak is never responsible for voicing a character. The yardak may be accompanied by a dairezen on a tambourine. The simple design of karagöz theatre makes it easy to transport; the puppets are all flat and the screen can be folded into a neat square, which is optimal for traveling karagöz artists. The screen and table behind it take up much less space than a stage so that a performance can be set up anywhere that is dark enough for shadows to be cast. A single hayalî impersonates every single character in the play by mimicking sounds, talking in different dialects, chanting or singing songs of the character in focus. He is normally assisted by an apprentice who sets up and tears down, and who hands him the puppets as needed. The latter task might also be performed by a sandıkkâr (from sandık, 'chest'). A yardak might sing songs, and a dairezen play the tambourine.[1]

Adaptations

[edit]Karagöz and Hacivat has also been adapted to other media, such as the 2006 Turkish film Killing the Shadows, directed by Ezel Akay.[7] The play was also featured in the Karagöz humor magazine that was published in Turkey between 1908 and 1955.[8]

In 2018, the character Hacivat appeared in the video game Fortnite: Battle Royale as a cosmetic outfit, introduced during the game's fifth season. It can be purchased with in-game currency.[9]

Karagöz plays existed in Tunisia until the start of the French protectorate, when they were banned because of their denunciation of colonialism. They are still present in national folklore.[10]

Due to the popularity of the plays in 19th-century Romania, today caraghios (feminine: caraghioasă, with variants caraghioz, caraghioază) has come to mean "ridicule, comical" in Romanian.[11]

See also

[edit]- Karagiozis, the Hellenized branch of the same shadow play tradition

- Wayang, the Indonesian or Malay shadow play tradition

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Ersin Alok, "Karagöz-Hacivat: The Turkish Shadow Play", Skylife - Şubat (Turkish Airlines inflight magazine), February 1996, p. 66–69.

- ^ Schneider, Irene (2001). "Ebussuud". In Michael Stolleis (ed.). Juristen: ein biographisches Lexikon; von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert (in German) (2nd ed.). München: Beck. p. 193. ISBN 3-406-45957-9.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Raphaela (1988). Everyday life in Ottoman Turkey. Internet Archive. New York, NY : Dorset Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-88029-175-0.

- ^ a b http://www.fatih.edu.tr/~ayasar/HIST349/Karagoz%20co-opted.pdf[permanent dead link], Serdar Oztürk

- ^ Rozen, Minna (2006). "The Ottoman Jews," in The Cambridge History of Turkey, Volume 3: the Later Ottoman Empire, 1603-1839, ed. Suraiya N. Faroqhi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 260.

- ^ Emin Senyer, Parts of Turkish Shadow Theatre Karagoz Archived 2011-09-02 at the Wayback Machine, karagoz.net. Accessed online 22 October 2007.

- ^ "Hacivat Karagöz Neden Öldürüldü? (2006) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ AKBABA, Bülent (2014). "İNKILÂP TARİHİ ÖĞRETİMİ İÇİN BİR KAYNAK: KARAGÖZ DERGİSİ". 22 (2): 12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Nicol, Haru (6 September 2018). "Fortnite Hacivat Skin: Epic Skin Leaked". GameRevolution. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Baba, Arouj. "Karakouz Ettounsi". Blogger.com. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "dexonline". dexonline.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 12 May 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Aykan, Bahar (2015). "'Patenting' Karagöz: UNESCO, nationalism and multinational intangible heritage". International Journal of Heritage Studies. 21 (10): 949–961. doi:10.1080/13527258.2015.1041413. S2CID 147307492.

- Kudret, Cevdet. 2004. Karagöz. İstanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları. 119., Sanat, 2111. ISBN 975-08-0862-2

External links

[edit]- Fictional characters introduced in the 16th century

- Theatre of Turkey

- Puppetry in Turkey

- Puppets

- Culture in Bursa

- Turkish words and phrases

- Fictional Turkish people

- Turkish folklore

- Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity

- Shadow play

- Fictional duos

- Fictional characters from the 14th century