Denali

| Denali | |

|---|---|

From the north, with Wonder Lake in the foreground | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 20,310 ft (6,190 m) top of snow[1][2] NAVD88 |

| Prominence | 20,194 ft (6,155 m)[3] |

| Parent peak | Aconcagua[3] |

| Isolation | 4,621.1 mi (7,436.9 km)[3] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 63°04′10″N 151°00′27″W / 63.0695°N 151.0074°W[4] |

| Geography | |

| |

| Interactive map of Denali | |

| Location | Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska, U.S. |

| Parent range | Alaska Range |

| Topo map | USGS Mt. McKinley A-3 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | June 7, 1913 by |

| Easiest route | West Buttress Route (glacier/snow climb) |

Denali (/dəˈnɑːli/;[5][6] also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name)[7] is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of 20,310 feet (6,190 m) above sea level. It is the tallest mountain in the world from base-to-peak on land, measuring 18,000 ft (5,500 m),[8] with a topographic prominence of 20,194 feet (6,155 m)[3] and a topographic isolation (the distance to the nearest peak of equal or greater height) of 4,621.1 miles (7,436.9 km),[3] Denali is the third most prominent and third-most isolated peak on Earth, after Mount Everest and Aconcagua. Located in the Alaska Range in the interior of the U.S. state of Alaska, Denali is the centerpiece of Denali National Park and Preserve.

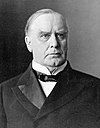

The Koyukon people who inhabit the area around the mountain have referred to the peak as "Denali" for centuries. In 1896, a gold prospector named it "Mount McKinley" in support of then-presidential candidate William McKinley, who later became the 25th president; McKinley's name was the official name recognized by the federal government of the United States from 1917 until 2015. In August 2015, 40 years after Alaska had done so, the United States Department of the Interior announced the change of the official name of the mountain to Denali.[9][10] On January 20, 2025, Donald Trump signed an executive order requiring the Secretary of the Interior to revert this name change within 30 days of the order's signing.[11]

In 1903, James Wickersham recorded the first attempt at climbing Denali, which was unsuccessful. In 1906, Frederick Cook claimed the first ascent, but this ascent is unverified and its legitimacy questioned. The first verifiable ascent to Denali's summit was achieved on June 7, 1913, by climbers Hudson Stuck, Harry Karstens, Walter Harper, and Robert Tatum, who went by the South Summit. In 1951, Bradford Washburn pioneered the West Buttress route, considered to be the safest and easiest route, and therefore the most popular currently in use.[12]

On September 2, 2015, the U.S. Geological Survey measured the mountain at 20,310 feet (6,190 m) high,[1] 10 ft lower than the 20,320 feet (6,194 m) measured in 1952 using photogrammetry.

Geology and features

Denali is a granitic pluton, mostly pink quartz monzonite, lifted by tectonic pressure from the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the North American Plate; at the same time, the sedimentary material above and around the mountain was stripped away by erosion.[13][14] The forces that lifted Denali also caused many deep earthquakes in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. The Pacific Plate is seismically active beneath Denali, a tectonic region that is known as the "McKinley cluster".[15]

Structural geology

The high topography of Denali is related to the complex structural relationships created by the right-lateral Denali Fault and Denali Fault Bend. The Denali Fault is caused by stresses created by the low-angle subduction of the Yakutat microplate underneath Alaska. The Denali Fault Bend is characterized as a gentle restraining bend.[16] The Denali Fault Bend represents a curvature in the Denali Fault that is approximately 75 km long. This curvature creates what is known as a "space problem." As the right-lateral movement along the Denali Fault continues, high compressional forces created at the fault bend essentially push the crust up in a vertical fashion. The longer the crust stays within the restraining bend, the higher the topography will be. Several active normal faults north of the restraining bend have recently been mapped with slip rates of approximately 2–6 mm/year.[16] These normal faults help to accommodate the unusual curvature of the restraining bend.[citation needed]

Elevation

Denali has a summit elevation of 20,310 feet (6,190 m) above sea level, making it the highest peak in North America and the northernmost mountain above 19,685 feet (6,000 m) elevation in the world.[1] Measured from base to peak at some 18,000 ft (5,500 m), it is among the largest mountains situated entirely above sea level. Denali rises from a sloping plain with elevations from 1,000 to 3,000 ft (300 to 910 m), for a base-to-peak height of 17,000 to 19,000 ft (5,000 to 6,000 m).[17] By comparison, Mount Everest rises from the Tibetan Plateau at a much higher base elevation. Base elevations for Everest range from 13,800 ft (4,200 m) on the south side to 17,100 ft (5,200 m) on the Tibetan Plateau, for a base-to-peak height in the range of 12,000 to 15,300 ft (3,700 to 4,700 m).[18] Denali's base-to-peak height is little more than half the 33,500 ft (10,200 m) of the volcano Mauna Kea, which lies mostly under water.[19]

Geography of the mountain

Denali has two significant summits: the South Summit is the higher one, while the North Summit has an elevation of 19,470 ft (5,934 m)[13] and a prominence of approximately 1,270 ft (387 m).[20] The North Summit is sometimes counted as a separate peak (see e.g., fourteener) and sometimes not; it is rarely climbed, except by those doing routes on the north side of the massif.

Five large glaciers flow off the slopes of the mountain. The Peters Glacier lies on the northwest side of the massif, while the Muldrow Glacier falls from its northeast slopes. Just to the east of the Muldrow, and abutting the eastern side of the massif, is the Traleika Glacier. The Ruth Glacier lies to the southeast of the mountain, and the Kahiltna Glacier leads up to the southwest side of the mountain.[21][22] With a length of 44 mi (71 km), the Kahiltna Glacier is the longest glacier in the Alaska Range.

Naming

The Koyukon Athabaskans who inhabit the area around the mountain have for centuries referred to the peak as Dinale or Denali. The name is based on a Koyukon word for 'high' or 'tall'.[23] During the Russian ownership of Alaska, the common name for the mountain was Bolshaya Gora (Russian: Большая Гора; bolshaya 'big'; gora 'mountain'), which is the Russian translation of Denali.[24] It was briefly called Densmore's Mountain in the late 1880s and early 1890s[25] after Frank Densmore, a gold prospector who was the first non-native Alaskan to reach the base of the mountain.[26]

In 1896, a gold prospector named it McKinley as political support for then-presidential candidate William McKinley, who became president the following year. The United States formally recognized the name Mount McKinley after President Wilson signed the Mount McKinley National Park Act of February 26, 1917.[27] In 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson declared the north and south peaks of the mountain the "Churchill Peaks", in honor of British statesman Winston Churchill.[28] The Alaska Board of Geographic Names changed the name of the mountain to Denali in 1975, which was how it is called locally.[7][29] However, a request in 1975 from the Alaska state legislature to the United States Board on Geographic Names to do the same at the federal level was blocked by Ohio congressman Ralph Regula, whose district included McKinley's home town of Canton.[30]

On August 30, 2015, just ahead of a presidential visit to Alaska, the Barack Obama administration announced the name Denali would be restored in line with the Alaska Geographic Board's designation.[10][31] U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell issued the order changing the name to Denali on August 28, 2015, effective immediately.[9] Jewell said the change had been "a long time coming".[32] The renaming of the mountain received praise from Alaska's senior U.S. senator, Lisa Murkowski (R-AK),[33] who had previously introduced legislation to accomplish the name change,[34] but it drew criticism from several politicians from President McKinley's home state of Ohio, such as Governor John Kasich, U.S. Senator Rob Portman, U.S. House Speaker John Boehner, and Representative Bob Gibbs, who described Obama's action as "constitutional overreach" because he said an act of Congress was required to rename the mountain.[35][36][37] The Alaska Dispatch News reported that the Secretary of the Interior has authority under federal law to change geographic names when the Board of Geographic Names does not act on a naming request within a "reasonable" period of time. Jewell told the Alaska Dispatch News that "I think any of us would think that 40 years is an unreasonable amount of time."[38]

In December 2024, President-elect Donald Trump stated that he planned to revert the mountain's official name back to Mount McKinley during his second term, in honor of President William McKinley. Trump had previously proposed changing the name in 2017, drawing opposition from Alaska governor Mike Dunleavy.[39] His 2024 proposal was strongly opposed by U.S. Senators from Alaska Lisa Murkowski (R) and Dan Sullivan (R), along with Alaska State Senator Scott Kawasaki (D).[40][41][42] On January 20, 2025, shortly after his second inauguration, Trump signed an executive order requiring the Secretary of the Interior to revert the Obama era name change within 30 days of signing (i.e: renaming Denali back to Mount McKinley in official maps and communications from the American federal government). The executive order does not change the name of Denali National Park, and international entities are not obliged to follow the federal government's name change.[further explanation needed][11][43][44]

Indigenous names for Denali can be found in seven different Alaskan languages. The names fall into two categories. To the south of the Alaska Range in the Dena'ina and Ahtna languages the mountain is known by names that are translated as 'big mountain'. To the north of the Alaska Range in the Lower Tanana, Koyukon, Upper Kuskokwim, Holikachuk, and Deg Xinag languages the mountain is known by names that are translated as 'the high one',[45] 'the tall one' (Koyukon, Lower and Middle Tanana, Upper Kuskokwim, Deg Xinag, and Holikachuk).[46]

Asked about the importance of the mountain and its name, Will Mayo, former president of the Tanana Chiefs Conference, an organization that represents 42 Athabaskan tribes in the Alaskan interior, said: "It's not one homogeneous belief structure around the mountain, but we all agree that we're all deeply gratified by the acknowledgment of the importance of Denali to Alaska's people."[47]

The following table lists the Alaskan Athabascan names for Denali.[46]

| Literal meaning | Native language | Spelling in the local practical alphabet |

Spelling in a standardized alphabet |

IPA transcription |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'The tall one' | Koyukon | Deenaalee | Diinaalii | /diːˈnæli/ |

| Lower Tanana | Deenadheet, Deenadhee | Diinaadhiit, Diinaadhii | /diˈnæðid/ | |

| Middle Tanana | Diineezi | Diinaadhi | /diˈnæði/ | |

| Upper Kuskokwim | Denaze | Diinaazii | /diˈnæzi/ | |

| Deg Xinag | Dengadh, Dengadhi | Dengadh, Dengadhe | /təˈŋað, təˈŋaðə/ | |

| Holikachuk | Denadhe | Diinaadhii | /diːˈnæðiː/ | |

| 'Big mountain' | Ahtna | Dghelaay Ce'e, Deghilaay Ce'e | Dghelaay Ke'e, Deghilaay Ke'e | /dʁɛˈlɔj ˈkɛʔɛ/ |

| Upper Inlet Dena'ina | Dghelay Ka'a | Dghelay Ka'a | /dʁəˈlaj ˈkaʔa/ | |

| Lower Inlet Dena'ina | Dghili Ka'a | Dghili Ka'a | /dʁili ˈkaʔa/ |

History

The Koyukon Athabaskans, living in the Yukon, Tanana and Kuskokwim basins, were the first Native Americans with access to the flanks of the mountain.[4] A British naval captain and explorer, George Vancouver, is the first European on record to have sighted Denali, when he noted "distant stupendous mountains" while surveying the Knik Arm of the Cook Inlet on May 6, 1794.[48] The Russian explorer Lavrenty Zagoskin explored the Tanana and Kuskokwim rivers in 1843 and 1844, and was likely the first European to sight the mountain from the other side.[49]

William Dickey, a New Hampshire-born resident of Seattle, Washington who had been digging for gold in the sands of the Susitna River, wrote, after his returning from Alaska, an account in the New York Sun that appeared on January 24, 1897.[50] His report drew attention with the sentence "We have no doubt that this peak is the highest in North America, and estimate that it is over 20,000 feet (6,100 m) high." Until then, Mount Logan in Canada's Yukon Territory was believed to be the continent's highest point. Though later praised for his estimate, Dickey admitted that other prospector parties had also guessed the mountain to be over 20,000 feet (6,100 m).[51] These estimates were confirmed in 1898 by the surveyor Robert Muldrow, who measured its elevation as 20,300 feet (6,200 m).[52]

On November 5, 2012, the United States Mint released a twenty-five cent piece depicting Denali National Park. It is the fifteenth of the America the Beautiful Quarters series. The reverse features a Dall sheep with the peak of Denali in the background.[53]

Climbing history

During the summer of 1902 scientist Alfred Brooks explored the flanks of the mountain as a part of an exploratory surveying party conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey. The party landed at Cook Inlet in late May, then traveled east, paralleling the Alaska Range, before reaching the slopes of Denali in early August. Camped on the flank of the mountain on August 3, Brooks noted later that while "the ascent of Mount McKinley had never been part of our plans", the party decided to delay one day so "that we might actually set foot on the slopes of the mountain". Setting off alone, with good weather, on August 4, Brooks aimed to reach a 10,000 feet (3,048 m) shoulder. At 7,500 feet (2,286 m), Brooks found his way blocked by sheer ice and, after leaving a small cairn as a marker, descended.[54] After the party's return, Brooks co-authored a "Plan For Climbing Mt McKinley", published in National Geographic magazine in January 1903, with fellow party-member and topographer D. L. Raeburn, in which they suggested that future attempts at the summit should approach from the north, not the south.[55] The report received substantial attention, and within a year, two climbing parties declared their intent to summit.[56]

During the early summer of 1903, Judge James Wickersham, then of Eagle, Alaska, made the first recorded attempt to climb Denali, along with a party of four others. The group attempted to get as close to the mountain as possible via the Kantishna river by steamer, before offloading and following Chitsia Creek with a poling boat, mules and backpacks, a route suggested to them by Tanana Athabaskan people they met along the way. The party received further navigational assistance at Anotoktilon, an Athabaskan hunting camp, where residents gave the group detailed directions to reach the glaciers at the foot of Denali. On reaching the mountain, the mountaineers set up base camp on the lower portion of Peters Glacier. Aiming for the northwest buttress of Denali's north peak, they attempted to ascend directly; however, crevasses, ice fall and the lack of a clear passage caused them to turn and attempt to follow a spur via Jeffery Glacier where they believed they could see a way to the summit. After a dangerous ascent, at around 10,000 feet (3,048 m), Wickersham found that the route did not connect as it had appeared from below, instead discovering "a tremendous precipice beyond which we cannot go. Our only line of further ascent would be to climb the vertical wall of the mountain at our left, and that is impossible." This wall, now known as the Wickersham Wall, juts 15,000 feet (4,572 m) upwards from the glacier to the north peak of Denali.[57] Because of the route's history of avalanche danger, it was not successfully climbed until 1963.[58]

Later in the summer of 1903, Dr. Frederick Cook directed a team of five men on another attempt at the summit. Cook was already an experienced explorer and had been a party-member on successful arctic expeditions commanded both by Robert Peary and Roald Amundsen.[57][59] Yet he struggled to obtain funding for his own expedition, eventually organizing it "on a shoestring budget"[60] without any other experienced climbers.[59] The party navigated up the Cook inlet and followed the path of the 1902 Brooks party towards Denali. Cook approached the mountain via the Peters Glacier, as Wickersham had done; however, he was able to overcome the ice fall that had caused the previous group to turn up the spur towards the Wickersham Wall. Despite avoiding this obstacle, on August 31, having reached an elevation of about 10,900 feet (3,322 m) on the northwest buttress of the north peak, the party found they had reached a dead end and could make no further progress. On the descent, the group completely circumnavigated the mountain, the first climbing party to do so.[61] Although Cook's 1903 expedition did not reach the summit, he received acclaim for the accomplishment, a 1,000 miles (1,609 km) trek in which he not only circled the entire mountain but also found, on the descent, an accessible pass northeast of the Muldrow Glacier following the headwaters of the Toklat and Chulitna rivers.[57]

In 1906, Cook initiated another expedition to Denali with co-leader Herschel Parker, a Columbia University professor of electrical engineering with extensive mountaineering experience. Belmore Browne, an experienced climber and five other men comprised the rest of the group. Cook and Parker's group spent most of the summer season exploring the southern and southeastern approaches to the mountain, eventually reaching a high point on Tokositna glacier, 25 miles (40 km) from the summit.[61] During their explorations the party mapped out many of the tributaries and glaciers of the Susitna river along the mountain's south flank.[57] As the summer ended, the team retreated to the coast and began to disperse. In September 1906, Cook and a single party-member, horseman Robert Barrill, journeyed towards the summit again, in what Cook later described as "a last desperate attempt" in a telegram to his financial backers.[57] Cook and Barrill spent 12 days in total on the attempt, and claimed to have reached the summit via the Ruth Glacier.[60]

Upon hearing Cook's claims, Parker and Browne were immediately suspicious. Browne later wrote that he knew Cook's claims were lies, just as "any New Yorker would know that no man could walk from the Brooklyn Bridge to Grant's Tomb [a distance of eight miles] in ten minutes."[60] In May 1907, Harper's Magazine published Cook's account of the climb along with a photograph of what appeared to be Barrill standing on the summit. By 1909, Barrill had recanted at least part of his story about the climb, and others publicly questioned the account; however, Cook continued to assert his claim[62] The controversy continued for decades. In 1956, mountaineers Bradford Washburn and Walter Gonnason tried to settle the matter, with Gonnason attempting to follow Cook's purported route to the summit. Washburn noted inconsistencies between Cook's account of locations of glaciers and found a spot, at 5,400 feet (1,646 m) and 19 miles (31 km) southeast of the summit that appeared identical to the supposed summit image. Gonnason was not able to complete the climb, but because he was turned back by poor weather, felt that this did not definitely disprove Cook's story.[63] In 1998, historian Robert Bryce discovered an original and un-cropped version of the "fake peak" photograph of Barrill standing on the promontory. It showed a wider view of surrounding features, appearing to definitively discount Cook's claim.[64]

Given the skepticism concerning Cook's story, interest in claiming the first ascent remained. Miners and other Alaskans living in Kantishna and Fairbanks wanted the honors to go to local men. In 1909, four Alaska residents – Tom Lloyd, Peter Anderson, Billy Taylor, and Charles McGonagall – set out from Fairbanks, Alaska during late December with supplies and dogs that were in part paid for by bettors in a Fairbanks tavern. By March 1910, the men had established a base camp near one of the sites where the Brooks party had been and pressed on from the north via the Muldrow glacier. Unlike some previous expeditions, they discovered a pass, since named McGonagall Pass, which allowed them to bypass the Wickersham Wall and access the higher reaches of the mountain. At roughly 11,000 feet (3,353 m), Tom Lloyd, old and less physically fit than the others, stayed behind. According to their account, the remaining three men pioneered a route following Karstens Ridge around the Harper Icefall, then reached the upper basin before ascending to Pioneer Ridge. The three men carried a 14-foot-long (4.3 m) spruce pole. Around 19,000 feet (5,791 m), Charles McGonagall, older and having exhausted himself carrying the spruce pole, remained behind. On April 3, 1910, Billy Taylor and Peter Anderson scrambled the final few hundred feet to reach the north peak of Denali, at 19,470 feet (5,934 m) high, the shorter of the two peaks. The pair erected the pole near the top, with the hope that it would be visible from lower reaches to prove they had made it.[65]

After the expedition, Tom Lloyd returned to Fairbanks, while the three others remained in Kantishna to mine. In Lloyd's recounting, all four men made it to the top of not only the north peak, but the higher south peak as well. When the remaining three men returned to town with conflicting accounts, the entire expedition's legitimacy was questioned.[66] Several years later, another climbing group would claim to have seen the spruce pole in the distance, supporting their north peak claim.[65] However, some continue to doubt they reached the summit. Outside of the single later climbing group, who were friendly with some of the Sourdough expedition men, no other group would ever see it. Jon Waterman, author of the book Chasing Denali, which explored the controversy, outlined several reasons to doubt the claim: There was never any photographic evidence. The four men climbed during the winter season, known for much more difficult conditions, along a route that has never been fully replicated. They were inexperienced climbers, ascending without any of the usual safety gear or any care for altitude sickness. They claimed to have ascended from 11,000 feet (3,353 m) to the top in less than 18 hours, unheard of at a time when siege-style alpinism was the norm.[67] Yet Waterman says "these guys were men of the trail. They didn't care what anybody thought. They were just tough SOBs."[68] He noted that the men were largely unlettered and that some of the ensuing doubt was related to their lack of sophistication in dealing with the press and the contemporary climbing establishment.[67]

In 1912, the Parker-Browne expedition nearly reached the summit, turning back within just a few hundred yards/meters of it due to harsh weather. On July 7, the day after their descent, a 7.4-magnitude earthquake shattered the glacier they had ascended.[69][70][71]

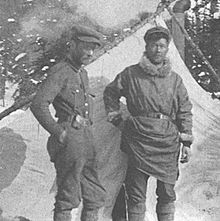

The first ascent of the main summit of Denali came on June 7, 1913, by a party directed by Hudson Stuck and Harry Karstens, along with Walter Harper and Robert Tatum. Karstens relocated to Alaska in the gold rush of 1897, and in subsequent years became involved in a variety of endeavors beyond mining, including helping establish dog mushing routes to deliver mail across vast swathes of territory and supporting expeditions led by naturalist Charles Sheldon near the base of Denali.[72] Stuck was an English-born Episcopal priest who came to Alaska by chance. He became acclimated to the often harsh Alaskan environment because of his many travels between far-flung outposts within his district, climbing mountains as a hobby.[73] At 21 years old, Harper was already known as a skilled and strong outdoorsman, the Alaska-born son of a Koyukon-Athabascan mother and Irish gold prospector father.[74][75] Tatum, also 21 years old, was a theology student working at a Tanana mission, and the least experienced of the team. His primary responsibility on the trip was as a cook.[76]

The team approached the peak from the north via the Muldrow glacier and McGonagall pass. While ferrying loads up to a camp at around 10,800 feet (3,292 m), they suffered a setback when a stray match accidentally set fire to some supplies, including several tents. The prior year's earthquake had left what had previously been described by the Parker-Browne expedition as a gentle slope ascended in no more than three days as a dangerous, ice-strewn morass on a knife-edged ridge (later named Karstens ridge). It would take the team three weeks to cover the same ground, as Karstens and Harper laboriously cut steps into the ice. On May 30, the team, with the help of some good weather, ascended to a new high camp, situated at 17,500 feet (5,334 m) in the Grand Basin between the north and south peaks. On June 7, the team made the summit attempt. Temperatures were below −20 °F (−29 °C) at times. Every man, and particularly Stuck, suffered from altitude sickness. By midday, Harper became the first climber to reach the summit, followed seconds later by Tatum and Karstens. Stuck arrived last, falling unconscious on the summit.[77]

Using the mountain's contemporary name, Tatum later commented, "The view from the top of Mount McKinley is like looking out the windows of Heaven!"[78] During the climb, Stuck spotted, via binoculars, the presence of a large pole near the North Summit; this report confirmed the Sourdough ascent, and it is widely believed presently that the Sourdoughs did succeed on the North Summit. However, the pole was never seen before or since, so there is still some doubt. Stuck also discovered that the Parker-Browne party were only about 200 feet (61 m) of elevation short of the true summit when they turned back. Stuck and Karstens' team achieved the uncontroversial first ascent of Denali's south peak; however, the news was met with muted interest by the wider climbing community. Appalachia Journal, then the official journal of the American Alpine Club, published a small notice of the accomplishment a year later.[73]

The mountain is climbed regularly nowadays. In 2003, around 58% of climbers reached the top. But by that time, the mountain had claimed the lives of nearly 100 mountaineers.[79] The vast majority of climbers use the West Buttress Route, pioneered in 1951 by Bradford Washburn,[12] after an extensive aerial photographic analysis of the mountain. Climbers typically take two to four weeks to ascend Denali. It is one of the Seven Summits; summiting all of them is a challenge for mountaineers.

On August 4, 2018, five people died in the K2 Aviation de Havilland Beaver (DHC-2) crash near Denali.[citation needed]

Accidents

From 1947 to 2018 in the United States "2,799 people were reported to be involved in mountaineering accidents"[80] and 11% of these accidents occurred on Denali.[80] Of these 2,799 accidents, 43% resulted in death and 8% of these deaths occurred on Denali.[80]

Timeline

- 1896–1902: Surveys by Robert Muldrow, George Eldridge, Alfred Brooks.[81]

- 1913: First ascent, by Hudson Stuck, Harry Karstens, Walter Harper, and Robert Tatum via the Muldrow Glacier route.[82]

- 1932: Second ascent, by Alfred Lindley, Harry Liek, Grant Pearson, Erling Strom. (Both peaks were climbed.)[83][84]

- 1947: Barbara Washburn becomes the first woman to reach the summit while her husband Bradford Washburn becomes the first person to summit twice.[85]

- 1951: First ascent of the West Buttress Route, led by Bradford Washburn.[12]

- 1954: First ascent of the very long South Buttress Route by George Argus, Elton Thayer (died on descent), Morton Wood, and Les Viereck. Deteriorating conditions behind the team pushed them to make the first traverse of Denali. The Great Traleika Cirque, where they camped just below the summit, was renamed Thayer Basin, in honor of the fallen climber.[86][87]

- 1954 (May 27) First ascent via Northwest Buttress to North Peak by Fred Beckey, Donald McLean, Charles Wilson, Henry Meybohm, and Bill Hackett [88]

- 1959: First ascent of the West Rib, now a popular, mildly technical route to the summit.[86]

- 1961: First ascent of the Cassin Ridge, named for Riccardo Cassin and the best-known technical route on the mountain.[89] The first ascent team members are: Riccardo Cassin, Luigi Airoldi, Luigi Alippi, Giancarlo Canali, Romano Perego, and Annibale Zucchi.[90][91]

- 1962: First ascent of the southeast spur, team of six climbers (C. Hollister, H. Abrons, B. Everett, Jr., S. Silverstein, S. Cochrane, and C. Wren)[92]

- 1963: A team of six climbers (W. Blesser, P. Lev, R. Newcomb, A. Read, J. Williamson, F. Wright) made the first ascent of the East Buttress. The summit was attained via Thayer Basin and Karstens Ridge. See AAJ 1964.

- 1963: Two teams make first ascents of two different routes on the Wickersham Wall.[93][94]

- 1967: First winter ascent, via the West Buttress, by Gregg Blomberg, Dave Johnston, Art Davidson and Ray Genet.[95]

- 1967: The 1967 Mount McKinley disaster; Seven members of Joe Wilcox's twelve-man expedition perish, while stranded for ten days near the summit, in what has been described as the worst storm on record. Up to that time, this was the third worst disaster in mountaineering history in terms of lives lost.[96] Before July 1967 only four men had ever perished on Denali.[97]

- 1970: First solo ascent by Naomi Uemura.[98]

- 1970: First ascent by an all-female team (the "Denali Damsels"), led by Grace Hoeman and the later famous American high altitude mountaineer Arlene Blum together with Margaret Clark, Margaret Young, Faye Kerr and Dana Smith Isherwood.[99][86]

- 1972: First descent on skis down the sheer southwest face, by Sylvain Saudan, "Skier of the Impossible".[100]

- 1976: First solo ascent of the Cassin Ridge by Charlie Porter, a climb "ahead of its time".[90]

- 1979: First ascent by dog team achieved by Susan Butcher, Ray Genet, Brian Okonek, Joe Redington, Sr., and Robert Stapleton.[86]

- 1984: Uemura returns to make the first winter solo ascent, but dies after summitting.[101] Tono Križo, František Korl and Blažej Adam from the Slovak Mountaineering Association climb a very direct route to the summit, now known as the Slovak Route, on the south face of the mountain, to the right of the Cassin Ridge.[102]

- 1988: First successful winter solo ascent. Vern Tejas climbed the West Buttress alone in February and March, summitted successfully, and descended.[103]

- 1990: Anatoli Boukreev climbed the West Rib in 10 hours and 30 mins from the base to the summit, at the time a record for the fastest ascent.[104]

- 1995: French skiers Jean-Noel Urban and Nicolas Bonhomme, made the first ski descent down the Wickersham Wall, most of the face was 50°.[105]

- 1997: First successful ascent up the West Fork of Traleika Glacier up to Karstens Ridge beneath Browne Tower. This path was named the "Butte Direct" by the two climbers Jim Wilson and Jim Blow.[106][107]

- 2015: On June 24, a survey team led by Blaine Horner placed two global positioning receivers on the summit to determine the precise position and elevation of the summit. The summit snow depth was measured at 15 ft (4.6 m). The United States National Geodetic Survey later determined the summit elevation to be 20,310 ft (6,190 metres).[1]

- 2019: On June 20, Karl Egloff (Swiss-Ecuadorian) set new speed records for the ascent (7h 40m) and round-trip (11h 44m), starting and returning to a base camp at 7,200 ft (2,200 m) on the Kahiltna Glacier.[108][109]

Weather station

The Japanese Alpine Club installed a meteorological station on a ridge near the summit of Denali at an elevation of 18,733 feet (5,710 m) in 1990.[110] In 1998, this weather station was donated to the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.[110] In June 2002, a weather station was placed at the 19,000-foot (5,800 m) level. This weather station was designed to transmit data in real-time for use by the climbing public and the science community. Since its establishment, annual upgrades to the equipment have been performed with instrumentation custom built for the extreme weather and altitude conditions. This weather station is the third-highest weather station in the world.[111]

The weather station recorded a temperature of −75.5 °F (−59.7 °C) on December 1, 2003. On the previous day of November 30, 2003, a temperature of −74.4 °F (−59.1 °C) combined with a wind speed of 18.4 miles per hour (29.6 km/h) to produce a North American record windchill of −118.1 °F (−83.4 °C).

Even in July, this weather station has recorded temperatures as low as −22.9 °F (−30.5 °C) and windchills as low as −59.2 °F (−50.7 °C).

Historical record

According to the National Park Service, in 1932 the Liek-Lindley expedition recovered a self-recording minimum thermometer left near Browne's Tower, at about 15,000 feet (4,600 m), on Denali by the Stuck-Karstens party in 1913. The spirit thermometer was calibrated down to −95 °F (−71 °C), and the lowest recorded temperature was below that point. Harry J. Liek took the thermometer back to Washington, D.C. where it was tested by the United States Weather Bureau and found to be accurate. The lowest temperature that it had recorded was found to be approximately −100 °F (−73 °C).[112] Another thermometer was placed at the 15,000-foot (4,600 m) level by the U.S. Army Natick Laboratory, and was there from 1950 to 1969. The lowest temperature recorded during that period was also −100 °F (−73 °C).[113]

Subpeaks and nearby mountains

Besides the North Summit mentioned above, other features on the massif which are sometimes included as separate peaks are:

- South Buttress, 15,885 feet (4,842 m); mean prominence: 335 feet (102 m)

- East Buttress high point, 14,730 feet (4,490 m); mean prominence: 380 feet (120 m)

- East Buttress, most topographically prominent point, 14,650 feet (4,470 m); mean prominence: 600 feet (180 m)

- Browne Tower, 14,530 feet (4,430 m); mean prominence: 75 feet (23 m)

Nearby peaks include:

- Mount Crosson

- Mount Foraker

- Mount Silverthrone

- Mount Hunter

- Mount Huntington

- Mount Dickey

- The Moose's Tooth

Taxonomic honors

- denaliensis

- Ceratozetella denaliensis (formerly Cyrtozetes denaliensis Behan-Pelletier, 1985) is a species of moss mite in the family Mycobatidae sv:Ceratozetella denaliensis

- Magnoavipes denaliensis Fiorillo et al., 2011 (literally "bird with large feet found in Denali") is a Magnoavipes ichnospecies of bird footprint from the Upper Cretaceous of Alaska and was a large heron-like bird (as large as a sandhill crane) with three toes and toe pads. pt:Magnoavipes denaliensis

- denali

- Cosberella denali (Fjellberg, 1985) is a springtail.

- Proclossiana aphirape denali Klots, 1940 is a Boloria butterfly species of the subfamily Heliconiinae of family Nymphalidae.

- Symplecta denali (Alexander, 1955) is a species of crane fly in the family Limoniidae.

- Tipula denali Alexander, 1969 is a species of crane fly in the family Tipulidae.

- denalii

- Erigeron denalii A. Nelson, 1945 or Denali fleabane is an Erigeron fleabane species.

- Papaver denalii Gjaerevoll 1963 is an Papaver species and synonym of Papaver mcconnellii.

- mckinleyensis or mackinleyensis

- Erebia mackinleyensis (Gunder, 1932) or Mt. McKinley alpine is a butterfly species of the subfamily Satyrinae of family Nymphalidae.

- Oeneis mackinleyensis Dos Passos 1965 or Oeneis mckinleyensis Dos Passos 1949 is a butterfly species of the subfamily Satyrinae of family Nymphalidae (synonym of Oeneis bore)

- Uredo mckinleyensis Cummins 1952 or Uredo mackinleyensis Cummins 1952 is a rust fungus species.

In popular culture

- In 2019, American educational animated series Molly of Denali premiered on PBS and CBC Kids. The show depicts the daily life and culture of Molly, a young Alaskan Native girl and vlogger.[114][115][116] The animated series has received acclaim for its representation of indigenous Alaskan culture.[117][118]

See also

- List of mountain peaks of North America

- List of U.S. states by elevation

- List of the highest major summits of the United States

- List of the most prominent summits of the United States

- List of the most isolated major summits of the United States

- Extremes on Earth

References

- ^ a b c d Mark Newell; Blaine Horner (September 2, 2015). "New Elevation for Nation's Highest Peak" (Press release). USGS. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Wagner, Mary Jo (November 2015). "Surveying at 20,000 feet". The American Surveyor. 12 (10): 10–19. ISSN 1548-2669.

- ^ a b c d e PeakVisor. "Denali". Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Denali". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917]. Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 3-12-539683-2.

- ^ "Denali". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Mr. Wyden, from the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (September 10, 2013). "Senate Report 113-93 – Designation of Denali in the State of Alaska". U.S. Government Publishing Office. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

The State of Alaska changed the name of the mountain to Denali in 1975, although the U.S. Board on Geographic Names has continued to use the name Mount McKinley. Today most Alaskans refer to Mount McKinley as Denali.

- ^ Adam Helman (2005). The Finest Peaks: Prominence and Other Mountain Measures. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-5995-4. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2012. On p. 20 of Helman (2005):"the base to peak rise of Mount McKinley is the largest of any mountain that lies entirely above sea level, some 18,000 ft (5,500 m)".

- ^ a b "Denali Name Change" (PDF) (Press release). U.S. Department of the Interior. August 28, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ a b Campbell, Jon (August 30, 2015). "Old Name Officially Returns to Nation's Highest Peak". U.S. Board on Geographic Names (U.S. Geological Survey). Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Ingle, Davis (January 21, 2025). "Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness". The White House. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c Roberts, David (April 2007). "The Geography of Brad Washburn (1910–2007)". National Geographic Adventure. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Brease, P. (May 2003). "GEO-FAQS #1 – General Geologic Features" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ Yoshikawa, Kenji; Okura, Yositomi; Autier, Vincent; Ishimaru, Satoshi (2006). "Secondary calcite crystallization and oxidation processes of granite near the summit of Mt. McKinley, Alaska". Géomorphologie. 12 (6). doi:10.4000/geomorphologie.147. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Hanson, Roger A. "Earthquake and Seismic Monitoring in Denali National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 23–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 10, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Burkett, Corey (2016). "Along-fault migration of the Mount McKinley restraining bend of the Denali fault defined by late Quaternary fault patterns and seismicity, Denali National Park & Preserve, Alaska". Tectonophysics. 693: 489–506. Bibcode:2016Tectp.693..489B. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2016.05.009. hdl:10919/101887.

- ^ Clark, Liesl (2000). "NOVA Online: Surviving Denali, The Mission". NOVA. Public Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Mount Everest (Map). 1:50,000. Cartography by Bradford Washburn. 1991. ISBN 3-85515-105-9. Prepared for the Boston Museum of Science, the Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, and the National Geographic Society

- ^ "Mountains: Highest Points on Earth". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ "Mount McKinley-North Peak, Alaska". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Denali National Park and Preserve". AreaParks.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Denali National Park". PlanetWare. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ Martinson, Erica (August 30, 2015). "McKinley no more: America's tallest peak to be renamed Denali". Alaska Dispatch News. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

The name "Denali" is derived from the Koyukon name and is based on a verb theme meaning "high" or "tall," according to linguist James Kari of the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, in the book "Shem Pete's Alaska." It doesn't mean "the great one," as is commonly believed, Kari wrote.

- ^ Dictionary of Alaska Place Names (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. 1976. p. 610. ISBN 0-944780-02-4.[permanent dead link].

- ^ Norris, Frank. "Crown Jewel of the North: An Administrative History of Denali National Park and Preserve, Vol. 1" (PDF). National Park Service. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Berton, Pierre (1990) [1972]. Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush 1896–1899 (revised ed.). Penguin Books Canada. p. 84. ISBN 0-14-011759-8. OCLC 19392422.

- ^ United States. Dept. of the Interior. Alaska Planning Group (1974). Proposed Mt. McKinley National Park Additions, Alaska: Final Environmental Statement. Alaska Planning Group, U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 558. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon B. (October 23, 1965). "Statement by the President Designating Two Peaks of Mount McKinley in Honor of Sir Winston Churchill". The American Presidency Project. University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Senator Ron Wyden (September 10, 2013). "Senate Report 113-93, Designation of Denali in the State of Alaska". US Government Publishing Office. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (1995). Drawing the Line: Tales of Maps and Cartocontroversy. Henry Holt and Company. p. 67. ISBN 0-8050-2581-2. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Richardson, Jeff (August 30, 2015). "Denali to be restored as name of North America's tallest mountain". Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. Archived from the original on January 3, 2022. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "President Obama OKs renaming of Mount McKinley to Denali". Alaska Dispatch News. August 30, 2015. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Matthew Smith "Murkowski thanks Obama for restoring Denali", (video) Archived September 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Alaska Public Radio, KNOM, Nome, August 31, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015

- ^ Memoli, Michael A. (August 30, 2015). "Mt. McKinley, America's Tallest Peak, is Getting Back its Original Name: Denali". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ "Ohio lawmakers slam Obama plans to rename Mt. McKinley 'Denali' during Alaska trip". Fox News. August 31, 2015. Archived from the original on August 31, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Glionna, John M. (August 31, 2015). "It's back to Denali, but some McKinley supporters may be in denial". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ "Ohio Gov. Kasich opposes changing name of Mount McKinley". KTUU. Associated Press. August 31, 2015. Archived from the original on September 2, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Martinson, Erica (August 30, 2015). "McKinley no more: North America's tallest peak to be renamed Denali". Alaska Dispatch News. Archived from the original on September 1, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Bohrer, Becky (January 20, 2025). "Trump order seeks to change the name of North America's tallest peak from Denali to Mount McKinley". AP News. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- ^ "President-elect Trump wants to again rename North America's tallest peak". AP News. December 23, 2024. Retrieved December 25, 2024.

- ^ Hussain, Zoe (December 23, 2024). "Trump vows to give tallest mountain its old name back". Retrieved December 25, 2024.

- ^ Venegas, Natalie (December 22, 2024). "Donald Trump Vows to Rename Tallest Mountain in United States". Newsweek.

- ^ "Trump to rename Gulf of Mexico, Denali". POLITICO. January 20, 2025. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ McHardy, Martha (January 21, 2025). "Not all Republicans are happy with Donald Trump's executive orders". Newsweek. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- ^ Hedin, Robert; Holthaus, Gary (1994). Alaska: Reflections on Land and Spirit. University of Arizona Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8165-1442-7. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ a b James, Kari (2003). "Names for Denali/Mt. McKinley in Alaska Native Languages". pp. 211–13. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Thiessen, Mark (August 31, 2015). "Renaming Mount McKinley to Denali: 9 questions answered". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Beckey 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Beckey 1993, p. 44.

- ^ Beckey 1993, p. 47.

- ^ Sherwonit, Bill (October 1, 2000). Denali: A Literary Anthology. Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. p. 9. ISBN 0-89886-710-X. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2016. See, particularly, chapter 4 (pp. 52–61): "Discoveries in Alaska" Archived July 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, 1897, by William A. Dickey.

- ^ Stuck, Hudson (1918). The Ascent of Denali (Mount McKinley). Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 159. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Denali National Park Quarter". National Park Quarters. January 20, 2011. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ Person, Grant (1953). A History of Mount McKinley National Park (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. pp. 9–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ Sherwonit, Bill (2012). To The Top of Denali: Climbing Adventures on North America's Highest Peak. Alaska Northwest Books. ISBN 978-0-88240-894-1.

- ^ Sfraga, Michael (1997). Distant Vistas: Bradford Washburn, Expeditionary Science and Landscape 1930–1960. p. 256.

- ^ a b c d e "Denali NP: Historic Resource Study (Chapter 3)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Beckey 1993, p. 139.

- ^ a b Isserman, Maurice (2016). Continental Divide: A History of American Mountaineering. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-29252-7.

- ^ a b c "A Long and Brutal Assault". Outside Online. May 2, 2004. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Beckey 1993, p. 295.

- ^ "Controversy - Frederick A. Cook Digital Exhibition". Ohio State University. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Berman, Eliza. "The Other Mount McKinley Controversy: Who Climbed Denali First". Time. Archived from the original on September 2, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Tierney, John (November 26, 1998). "Author Says Photo Confirms Mt. McKinley Hoax in 1908". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ a b "Denali NP: Historic Resource Study (Chapter 3)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ "Did they make it or fake it? Book tries to uncover truth about legendary Sourdough ascent of Denali". Anchorage Daily News. June 8, 2019. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Chasing Denali – A Story of the Most Unbelievable Feat in Mountaineering". Rock and Ice. November 2018. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ Condon, Scott (December 18, 2018). "Carbondale author explores if his heroes committed fraud or feat on Denali". Aspen Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ "North peak of Mount McKinley: A Timely Escape". The American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Heacox, Kim (2015). Rhythm of the Wild: A Life Inspired by Alaska's Denali National Park. Connecticut: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-4930-0389-1. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Stover, Carl W.; Coffman, Jerry L. (1993). Seismicity of the United States, 1568–1989 (revised ed.). United States Government Printing Office. p. 52. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

This earthquake was violent at Fairbanks and strong at Kennicott. The earth 'heaved and rolled' at the north base of Mt. McKinley and the country was scarred with landslides.

- ^ "Superintendent Harry Karstens". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Woodside, Christine (June 6, 2012). "Who Led the First Ascent of Denali?". Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "The Ultimate Triumph and Tragedy: Remembering Walter Harper 100 Years Later". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Harper-Haines, Jan. "Denali, A Universe". Alpinist. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Ehrlander, Mary (2017). Walter Harper, Alaska Native Son. University of Nebraska Press. p. 55.

- ^ "A Brief Account of the 1913 Climb of Denali". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Coombs & Washburn 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Glickman, Joe (August 24, 2003). "Man Against the Great One". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c DeLoughery, Emma P.; DeLoughery, Thomas G. (June 14, 2022). "Review and Analysis of Mountaineering Accidents in the United States from 1947–2018". High Altitude Medicine & Biology. 23 (2): 114–118. doi:10.1089/ham.2021.0085. PMID 35263173. S2CID 247361980. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Borneman 2003, p. 221.

- ^ Stuck, Hudson. The Ascent of Denali.

- ^ Borneman 2003, p. 320.

- ^ Verschoth, Anita (March 28, 1977). "Mount Mckinley On Cross-country Skis And Other High Old Tales". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ Waterman 1998, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d "Historical Timeline". Denali National Park and Preserve. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ^ MacDonald, Dougald (June 15, 2012). "Remembering Denali's Greatest Rescue". www.climbing.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Selters, Andy (2004) Ways to the Sky. Golden, CO: the American Alpine Club Press. ISBN 0-930410-83-1

- ^ "Denali (Mount McKinley)". SummitPost.org. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ a b "Cassin Ridge" (PDF). supertopo.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Cassin Ridge" (PDF). Cascadeimages.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "We Climbed our Highest Mountain: First ascent McKinley's SE Spur and South Face". Look. Vol. 26, no. 21. October 9, 1962. pp. 60–69. ISSN 0024-6336.

- ^ Geiger, John (2009). The Third Man Factor. Weinstein Books. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-60286-116-9. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ "Climb Mount McKinley, Alaska". National Geographic. August 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ Blomberg, Gregg (1968). "The Winter 1967 Mount McKinley Expedition". American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Tabor, James M. (2007). Forever on the Mountain: The Truth Behind One of Mountaineering's Most Controversial and Mysterious Disasters. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06174-1.

- ^ Babcock, Jeffrey T. (2012). Should I Not Return: The Most Controversial Tragedy in the History of North American Mountaineering!. Publication Consultants. ISBN 978-1-59433-270-8.

- ^ Beckey 1993, p. 214.

- ^ Beckey 1993, p. 298.

- ^ "Skiing Denali: The Fast Way Down". Adventure. September 12, 2013. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ "Exposure, Weather, Climbing Alone — Alaska Mount McKinley". Accident Reports. American Alpine Journal. 5 (2): 25. 1985. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Mount McKinley, South Face, New Route". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. 26 (58). Golden, Colorado: American Alpine Club: 174. 1985. ISSN 0065-6925. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Denali First Ascents and Interesting Statistics" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ Franz, Derek (June 23, 2017). "Katie Bono sets probable women's speed record on Denali". Alpinist Magazine. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "AAC Publications - North America, United States, Alaska, Alaska Range, Mount McKinley, Ski Descent of the Wickersham Wall". publications.americanalpineclub.org. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ "North America, United States, Alaska, Denali National Park, Denali, Butte Direct". American Alpine Journal. 40 (72). Golden, Colorado: American Alpine Club: 217. 1998. ISSN 0065-6925. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Secor 1998, p. 35.

- ^ "Karl Egloff - Denali (AK) - 2019-06-20". fastestknowntime.com. June 20, 2019. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Karl Egloff Smashes Denali Speed Record". Rock and Ice Magazine. June 21, 2019. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Rozell, Ned (July 17, 2003). "Mountaineering and Science Meet on Mt. McKinley". Ketchikan, Alaska: Sitnews. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Japanese install probe on tallest US peak". The Japan Times. July 17, 2006. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Dixon, Joseph S. (1938). Fauna of the National Parks of the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Wunderground.com – Weather Extremes: The Coldest Places On Earth". Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "Get An Exclusive Sneak Peek At A Brand New Episode Of 'Molly Of Denali' On PBS Kids". Romper. April 28, 2020. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "PBS Kids orders animated series from Atomic Cartoons" Archived September 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Playback, May 9, 2018.

- ^ "Upfronts '18: CBC debuts 17 new series" Archived September 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Playback, May 24, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Julia (July 15, 2019). "With 'Molly of Denali,' PBS Raises Its Bar for Inclusion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Peabody 30 Winners". August 24, 2020. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

Bibliography

- Beckey, Fred (1993). Mount McKinley: Icy Crown of North America. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-646-4.

- Borneman, Walter R. (2003). Alaska: Saga of a Bold Land. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-050306-8. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Coombs, Colby; Washburn, Bradford (1997). Denali's West Buttress: A Climber's Guide to Mount McKinley's Classic Route. Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-516-5.

- Davidson, Art (2004). Minus 148°: First Winter Ascent of Mt. McKinley (7th ed.). The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-687-1. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Freedman, Lew (1990). Dangerous Steps: Vernon Tejas and the Solo Winter Ascent of Mount McKinley. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-2341-1.

- Rodway, George W. (March 2003). "Paul Crews' "Accident on Mount McKinley"—A Commentary". Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. 14 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2003)014[0033:PCAOMM]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1080-6032. PMID 12659247.

- Scoggins, Dow (2004). Discovering Denali: A Complete Reference Guide to Denali National Park and Mount McKinley, Alaska. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-75058-0. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Secor, R. J. (1998). Denali Climbing Guide. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2717-3. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Stuck, Hudson (1988). The ascent of Denali (Mount McKinley): a narrative of the first complete ascent of the highest peak in North America. Wolfe Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-935632-69-9. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Washburn, Bradford; Roberts, David (1991). Mount McKinley: the conquest of Denali. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-3611-9.

- Waterman, Jonathan; Washburn, Bradford (1988). High Alaska: A Historical Guide to Denali, Mount Foraker, & Mount Hunter. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-930410-41-4. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Waterman, Jonathan (1998). In the Shadow of Denali: Life and Death on Alaska's Mt. McKinley. Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-726-3. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- Waterman, Jonathan (1991). Surviving Denali: A Study of Accidents on Mt. McKinley, 1910-1990. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1-933056-66-1. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Wilson, Rodman; Mills, William J. Jr.; Rogers, Donald R.; Propst, Michael T. (June 1978). "Death on Denali". Western Journal of Medicine. 128 (6): 471–76. LCCN 75642547. OCLC 1799362. PMC 1238183. PMID 664648.

Further reading

- Drury, Bob (2001). The Rescue Season: A True Story of Heroism on the Edge of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-86479-7. OCLC 44969545. Also titled The Rescue Season: The Heroic Story of Parajumpers on the Edge of the World. About the US Air Force's 210th Rescue Squadron during the 1999 climbing season on Denali.

External links

- Mt. McKinley Weather Station

- Denali at SummitPost

- Timeline of Denali climbing history, National Park Service Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- The Ascent of Denali (Mount McKinley) at Project Gutenberg

- Mount Mckinley Quadrangle Publications, Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys

- Denali

- North American 6000 m summit

- Alaska Range

- Seven Summits

- Highest points of United States national parks

- Sacred mountains of the Americas

- Mountains of Denali Borough, Alaska

- Denali National Park and Preserve

- Religious places of the Indigenous peoples of North America

- Highest points of U.S. states

- Highest points of countries

- Naming controversies

- Ahtna