Moulin Rouge

The Moulin Rouge in 2011 | |

| |

| Address | 82 Boulevard de Clichy Paris France |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 48°53′03″N 2°19′57″E / 48.88417°N 2.33250°E |

| Type | Cabaret |

| Capacity | 850 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 6 October 1889 |

| Architect | Adolphe Willette and Édouard-Jean Niermans |

| Website | |

| Moulinrouge.fr | |

Moulin Rouge[1] (/ˌmuːlæ̃ ˈruːʒ/, French: [mulɛ̃ ʁuʒ]; lit. '"Red Mill"') is a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche, the intersection of, and terminus of Rue Blanche.

In 1889, the Moulin Rouge was co-founded by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Paris Olympia. The original venue was destroyed by fire in 1915, reopening in 1925 after rebuilding. Moulin Rouge is southwest of Montmartre, in the Paris district of Pigalle on Boulevard de Clichy in the 18th arrondissement, and has a landmark red windmill on its roof. The closest métro station is Blanche.

Moulin Rouge is best known as the birthplace of the modern form of the can-can dance. Originally introduced as a seductive dance by the courtesans who operated from the site, the can-can dance revue evolved into a form of entertainment of its own and led to the introduction of cabarets across Europe. Today, the Moulin Rouge is a tourist attraction, offering predominantly musical dance entertainment for visitors from around the world. The club's decor still contains much of the romance of fin de siècle France.

History

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Creation and early success

[edit]On 6 October 1889, the Moulin Rouge opened as the Jardin de Paris,[2][3][4] an outdoor garden café-concert,[5] at the foot of the Montmartre hill. Its creator Joseph Oller and his Manager Charles Zidler were formidable businessmen who understood the public's tastes. The aim was to attract wealthy individuals to experience the ambiance of the fashionable district of Montmartre, which was perceived as a form of slumming. The elaborate setting, featuring a garden adorned with a large elephant, provided an environment where individuals from various social strata could interact. This included workers, local residents, artists, the middle class, businessmen, stylish women, and tourists passing through Paris. Nicknamed "The First Palace of Women" by Oller and Zidler, the cabaret swiftly garnered significant acclaim. Key factors contributing to its success included:[1]

- Revolutionary auditorium architecture enabling rapid changes of décor and fostering social interaction among all patrons.

- Champagne evenings characterized by lively entertainment and dancing, featuring regularly changing amusing acts like Le Pétomane.

- A new dance, inspired by the quadrille and gaining popularity, known as the Can-can. Dancers performed this energetic dance to a lively rhythm while wearing provocative costumes.

- Prominent dancers from the era included figures such as la Goulue, Jane Avril, la Môme Fromage, Grille d'Egout, Nini Pattes en l'Air, Yvette Guilbert, Valentin le désossé, and the clown Cha-U-Kao.

- A favored venue among artists, including Toulouse-Lautrec, whose posters and paintings contributed to the rapid and international renown of the Moulin Rouge.

- Art and posters

-

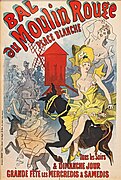

Bal au Moulin Rouge, Place Blanche, poster by Jules Chéret, 1889

-

Zidler's assistant and Moulin-Rouge manager, Tremolada, pointing at Jules Chéret's 1889 poster, Bal du Moulin Rouge with Toulouse-Lautrec, Place Blanche, Paris, 1892[6]

-

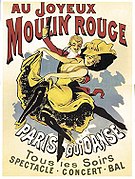

Advertising poster of the Moulin Rouge by Alfred Choubrac, 1896

-

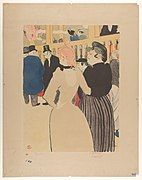

At the Moulin Rouge, La Goulue and her Sister (Au Moulin Rouge, La Goulue et sa sœur) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1892

-

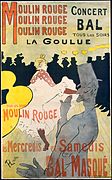

Poster by Jules Chéret, 1890

Greatest moments

[edit]During its early years, the Moulin Rouge featured extravagant shows inspired by the circus, along with attractions that gained widespread fame, such as Pétomane. Concert-dances were organized daily at 10 pm. Between 1886 and 1910, the comic duo Footit and Chocolat, comprising a white authoritarian clown and a black long-suffering Auguste, gained popularity and were frequently featured on Moulin Rouge posters. On 19 April 1890, the first revue, "Circassiens et Circassiennes," debuted. On 26 October 1890, during a private visit to Paris, the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, reserved a table to witness a quadrille at the Moulin Rouge, where La Goulue famously greeted him with the exclamation, "Hey, Wales, the champagne's on you!" In 1891, Toulouse-Lautrec created his first poster for the Moulin Rouge, featuring La Goulue. In 1893, the "Bal des Quat'z'Arts" sparked scandal with its procession featuring a nude Cleopatra surrounded by young naked women. On 12 November 1897, the Moulin Rouge closed for the first time to mourn the passing of its manager and co-founder, Charles Zidler. Yvette Guilbert paid homage to him, saying, "You have the knack of creating popular pleasure, in the finest sense of the word, of entertaining crowds with subtlety, according to the status of those to be entertained." In 1900, the Universal Exhibition attracted visitors from around the world to the Moulin Rouge, solidifying Paris's reputation as a city of decadent pleasure. This led to the establishment of imitation "Moulin Rouges" and "Montmartres" in many other countries.

Operetta and grand shows

[edit]

In January 1903, the Moulin Rouge underwent renovation and improvement under the direction of Édouard Niermans, a prominent architect of the Belle Époque era, amongst other works he designed the brasserie Mollard, the Casino de Paris, the Folies Bergère in Paris, the Palace Hôtel in Ostend in Belgium, the rebuilding of the Hôtel du Palais in Biarritz, and the creation of the Hotel Negresco on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. This included the addition of aperitif concerts, attracting the fashionable elite for dining and entertainment in a luxurious setting.

Until the outbreak of the First World War, the Moulin Rouge became renowned for its operetta performances. Successful shows during this period included Voluptata, La Feuille de Vigne, Le Rêve d'Egypte, Tais-toi tu m'affoles, among others, each with evocative titles. On 3 January 1907, during the performance of Le Rêve d'Egypte, Colette exchanged scandalous kisses that revealed her connection to the Duchess of Morny, leading to the show being banned. Mistinguett made her debut at the Moulin Rouge on 29 July 1907 in the Revue de la Femme, showcasing her undeniable talent. She quickly rose to fame, achieving immense success the following year with Max Dearly in La Valse chaloupée. Born into poverty, Mistinguett's sharp wit and determination propelled her to become a successful businesswoman, touring extensively across Europe and the United States. On 9 April 1910, a former lady-in-waiting to Empress Eugénie attended a showing of the Revue Amoureuse at the Moulin Rouge and was so captivated by the faithful recreation of a ceremony for the return of troops from Italy that she exclaimed, "Long Live the Empress!" Tragically, on 27 February 1915, the Moulin Rouge was destroyed by fire during building works, resulting in a nine-year closure.[7] In 1925, the rebuilt Moulin Rouge reopened its doors to the public.

-

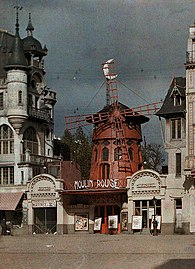

The Moulin Rouge, June 1912

-

The Moulin Rouge in Autochrome Lumière color, before the 1915 fire

-

Moulin Rouge, la revue Cache Ton Nu !, 24 June 1914, by Stéphane Passet[8]

Mistinguett years

[edit]

Following World War I, Francis Salabert assumed management of the Moulin Rouge. As a businessman rather than a showman, he entrusted Jacques-Charles, a prominent impresario, with revitalizing the cabaret. The Moulin Rouge experienced a resurgence with the performances of stars such as Mistinguett, Jeanne Aubert, and Maurice Chevalier, as well as the introduction of American revues featuring the Hoffmann Girls.

In 1923, composer and conductor Raphaël Beretta proposed a reconstruction of the Moulin Rouge's music hall on a larger scale. The iconic mill structure, supported by a central facade adorned with oval dormers, was designed by Gesmar, a 20-year-old set designer whose work became synonymous with the venue.

Jacques-Charles and Mistinguett collaborated on several acclaimed revues, including:

1925: Revue Mistinguett

1926: Ça c'est Paris

1928: Paris qui tourne

During a 1927 performance, an incident occurred when female dancers emerged from multi-tiered artificial cakes covered in real frosting. The slippery cake cream on their high heels caused them to repeatedly slip and fall on stage, resulting in disruptions to the show.[9]

Mistinguett's tenure at the Moulin Rouge produced enduring songs such as "Valencia," "Ça c'est Paris" (both by Jose Padilla), "Il m'a vue nue," "On m' suit," and "La Java de Doudoune," the latter performed with Jean Gabin.

After Mistinguett

[edit]In 1929, Mistinguett retired from the stage, leading to the transformation of the Moulin Rouge's ballroom into an ultra-modern Night Club.

From June to August 1929, the revue Lew Leslie's Blackbirds, featuring jazz singer and Broadway star Adelaide Hall,[10] along with a troop of a hundred black artists accompanied by the Jazz Plantation Orchestra, became the hit of the season at the Moulin Rouge.[11]

In 1937, the Cotton Club, renowned in New York, was showcased at the Moulin Rouge, alongside performances by Ray Ventura and his Collegians.

During the Second World War (1939–1945), the Moulin Rouge was highlighted in the German Occupation Guide as a must-visit attraction in Paris.[12] Its stage shows continued for the occupation troops and were mentioned in autobiographies of German officers such as Ernst Jünger and Gerhard Heller.[13] The Germans facilitated "recreational visits" in Paris for their troops, promoting the motto "Jeder einmal in Paris" (everyone once in Paris). The widespread prostitution during the occupation eventually led to the implementation of the Loi Marthe Richard in 1946, which closed bordellos and reduced stage shows to dancing events.

In 1944, shortly after the liberation of Paris, Edith Piaf, who had performed frequently at social gatherings for German forces during the war, returned to the stage at the Moulin Rouge. She was accompanied by Yves Montand, a newcomer chosen to perform with her.

-

Vu, issue N°77, Wednesday, 4 September 1929, front cover, with Adelaide Hall star of Blackbirds at the Moulin Rouge, titled "Au revoir Black Birds !", saying farewell after a production run of four months

-

Moulin Rouge Cinema at night, 1936.

-

Two German soldiers, with two women, in front of the Moulin Rouge, during the Nazi occupation, June 1940.

Renewal

[edit]

On 22 June 1951, Georges France, also known as Jo France, founder of the Balajo in Paris, acquired the Moulin Rouge and initiated extensive renovation efforts. Architects Pierre Devinoy, Bernard de La Tour d’Auvergne, and Marion Tournon-Branly were tasked with enhancing and outfitting the new auditorium. The envisioned décor by Jo France, largely executed by Henri Mahé, a prominent designer of the era, remains intact to this day.

The return of evening dances, acts, and the iconic French cancan marked a revival at the Moulin Rouge. On 19 May 1953, the 25th "Bal des Petits Lits Blancs," organized by novelist Guy des Cars, attracted notable figures such as French President Vincent Auriol and featured Bing Crosby's European stage debut. Between 1951 and 1960, the stage saw performances by renowned artists including Luis Mariano, Charles Trénet, and Josephine Baker.

In 1955, Jo France transferred ownership to brothers Joseph and Louis Clérico, proprietors of Le Lido,[14] with Jean Bauchet assuming the managerial role. The tradition of the French cancan continued, choreographed by Ruggero Angeletti. Doris Haug established the "Doris's Girls" troop in 1957, initially comprising four girls and later expanding to sixty.

Transformations in 1959 included renovations to the Moulin Rouge's kitchens, while the introduction of The Revue Japonaise in 1960 showcased Japanese artists and popularized Kabuki in Montmartre. In 1962, Jacki Clérico, son of Joseph Clérico, assumed leadership,[14] ushering in an era of expansion with the enlargement of the auditorium, installation of a giant aquarium, and the introduction of the first aquatic ballet. The Revue Cancan, devised by Doris Haug and Ruggero Angeletti, premiered the same year.

Since 1963, following the success of the Frou-Frou revue, Jacki Clérico adopted a tradition of naming revues with titles beginning with the letter F. Throughout these productions, the famed French cancan remained a staple feature:[15]

- 1963–1965: Frou-Frou

- 1965–1967: Frisson

- 1967–1970: Fascination

- 1970–1973: Fantastic

- 1973–1976: Festival

- 1976–1978: Follement

- 1978–1983: Frénésie

- 1983–1988: Femmes, femmes, femmes

- 1988–1999: Formidable

- Since 1999: Féerie

On 7 September 1979, the Moulin Rouge marked its 90th anniversary, reaffirming its status as a prominent fixture in Parisian nightlife. The celebration featured an array of stars, including Ginger Rogers, Thierry Le Luron, Dalida, and Charles Aznavour, among others. Notable events followed, including a special presentation of the show to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on 23 November 1981. The venue hosted renowned performers such as Liza Minnelli in February 1982, followed by gala performances with Dean Martin in July 1984 and Frank Sinatra in September 1984. A milestone occurred on 1 December 1986, when world-renowned dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov premiered an original ballet by Maurice Béjart at the Moulin Rouge.

In February 1988, despite the original building's destruction in 1915, the Moulin Rouge celebrated its centenary with the premiere of the revue "Formidable," a prestigious event attended by Prince Edward. Subsequent events included performances in London and gala celebrations featuring an array of luminaries, including Charles Aznavour, Ella Fitzgerald, and Jerry Lewis. Over the years, the Moulin Rouge continued to host charitable events, such as the Cartier gala in support of the Artists' Foundation against AIDS in 1994, and the Lancôme gala in 1995. The centenary revue "Formidable" concluded in November 1999, paving the way for the debut of the new revue "Féerie" in December 1999.

In 2008, soloist dancer Aleksandar Josipović served as master of ceremonies at the 53rd Eurovision Song Contest. The venue's global reach extended further in February 2009 when it was showcased as part of the Year of France in Brazil and the Rio Carnival on Copacabana Beach. However, on 13 January 2013, Moulin Rouge owner Jacki Clérico passed away,[14] followed by the death of Doris Haug, founder of the Doris's Girls, on 10 August 2014.[16] Despite these losses, the Moulin Rouge celebrated its 125th anniversary on 6 October 2014.

On 25 April 2024, the cabaret's windmill blades collapsed onto the street, resulting in damage to the facade. No injuries were reported.[17][7] The windmill was restored on 5 July that year, in time for the Olympic torch relay that passed through the area on 15 July.[18][19]

Documentaries

[edit]- Quadrille dansé par les étoiles du Moulin-Rouge 1,2&3 (1899–1902), France – produced by Pathé (3 episodes of 20 min)

- An Evening at the Moulin Rouge (1981), Réalisé par David Niles, produced by HBO (length : 60 min)

- Les Dessous du Moulin Rouge (2000), Réalisé par Nils Tavernier, produced by Little Bear (length : 52 min)

- Coulisses d'une revue, le Moulin Rouge (2001), directed by par Philippe Pouchain and Yves Riou (length : 60 min)

- Moulin Rouge Forever (2002), directed by Philippe Pouchain and Yves Riou (length: 55 min)

- Moulin Rouge : la restauration and Une vie de passion au Moulin Rouge. Two documentaries available with the Moulin Rouge movie of John Huston.

- Au cœur du Moulin Rouge (At the heart of Moulin Rouge) (2012), Directed by Marie Vabre, produced by 3e Œil Productions (90 min).

Books

[edit]Illustrated books

[edit]- The Moulin Rouge (1989), by Jacques Pessis and Jacques Crépineau – Publisher: St Martins

- The Moulin Rouge (2002), by Jacques Pessis and Jacques Crépineau – Publisher: Le Cherche-Midi

- Moulin Rouge, Paris (2002), by Christophe Mirambeau – Publisher: Assouline

- Flipbook Moulin Rouge Paris France 23h18, Paris (2003), by Jean-Luc Planche – Publisher: Youpeka

About Moulin Rouge and its characters

[edit]- Duret, Théodore (1920). Lautrec. Paris: Bernheim-Jeune – via Internet Archive.

- Pierre La Mure Moulin Rouge (1950), a novel based on the life of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Random House

- Jose Shercliff Jane Avril of the Moulin Rouge (1954), Macrae Smith Co

- Jean Nohain and François Caradec Le Pétomane 1857–1945 a tribute to the unique act which shook and shattered the Moulin-Rouge (1967), Souvenir Press

- Robert Burleigh Toulouse-Lautrec : The Moulin Rouge and the City of Light, (2003), Harry N. Abrams

Legacy

[edit]Enterprises

[edit]The Moulin Rouge in Paris was a source of inspiration for:

- Moulin Rouge Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada

- The nude revues at the Windmill Theatre, created by Laura Henderson and Vivian Van Damm

- The Moulin Rouge restaurant in Park Street, Kolkata is inspired by this cabaret along with the symbolic windmill.

Film

[edit]- Moulin Rouge Dancers 1&2 (1898) – United States – silent film about the Moulin Rouge

- Queen of the Moulin Rouge (1922), directed by Ray C. Smallwood and Peter Milne – United States – silent film about the Moulin Rouge

- Le Fantôme du Moulin Rouge (1925), directed by René Clair – with Sandra Milovanoff and Georges Vaultier

- Moulin Rouge (1928), directed by Ewald André Dupont – With Olga Chekhova, Eve Gray and Jean Bradin

- Moulin Rouge also titled L'étoile du Moulin Rouge (1934), directed by Sidney Lanfield – with Constance Bennett – United States

- La Chaste Suzanne (1937/1938), directed by André Berthomieu – with Raimu and Henri Garat

- La P'tite femme du Moulin Rouge (1945), directed by Benito Perojo – with Alberto Bello, Héctor Calcaño, Homero Cárpena, and Tilda Thamar

- A Night at the Moulin Rouge (1951) is a film (also circulated under the title Ding Dong!) of burlesque acts of the Moulin Rouge club in Oakland, California

- Moulin Rouge (1952), directed by John Huston- with José Ferrer, Suzanne Flon and Zsa Zsa Gabor

- French Cancan (1955), directed by Jean Renoir – with Jean Gabin, Françoise Arnoul, María Félix, Jean-Roger Caussimon, Gianni Esposito, Philippe Clay, and Michel Piccoli

- A Night at the Moulin Rouge (1957), directed by Jean-Claude Roy – with Tilda Thamar, Noël Roquevert, Armand Bernard and Jean Tissier

- La Chaste Suzanne (1963), directed by Luis César Amadori – with Armand Mestral, Noël Roquevert and Frédéric Duvallès – Spain/France

- Moulin Rouge! (2001), directed by Baz Luhrmann, with Ewan McGregor, Nicole Kidman, John Leguizamo, Jim Broadbent, and Richard Roxburgh

- Midnight in Paris (2011), directed by Woody Allen, with Owen Wilson, Marion Cotillard, Rachel McAdams, Tom Hiddleston, Corey Stoll, Kathy Bates, and Adrien Brody – Spain, US

Music

[edit]- The music video for the "Lady Marmalade" cover act by Christina Aguilera, Pink, Lil' Kim, and Mýa was filmed on a replica set of the Moulin Rouge

- Prince and his concert film Sign o' the Times (1987) featured the Moulin Rouge as part of his stage venue and props

- The second music video for The Killers' song "Mr. Brightside" was set in the Moulin Rouge

- It is the title of a 2014 single sung by Kamijo

Stage adaptations

[edit]- The 2018 musical Moulin Rouge! is an adaptation of the 2001 Baz Luhrmann film.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Histoire du Moulin Rouge". MoulinRouge.fr.

- ^ Dubé, Paul; Marchioro, Jacques. "Cafés concerts et music-halls H : Horloge, L' – Champs-Élysées, 8e". du temps des cerises aux feuilles mortes .net. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Dubé, Paul; Marchioro, Jacques. "Cafés concerts et music-halls J : Jardin de Paris – Champs-Élysées, 8e". du temps des cerises aux feuilles mortes .net. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "L'entrée du Jardin de Paris". NYPL Digital Collections. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Lawrence, Katrina (1 July 2019). "In Search of the Lost Moulin Rouge". Paris For Dreamers.

- ^ "Toulouse-Lautrec et Tremolada, adjoint de Zidler au Moulin-Rouge, 1892". La collection Toulouse-Lautrec (in French). Musées Occitanie. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ a b Henley, Jon (25 April 2024). "Moulin Rouge windmill sails collapse in Paris". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ • "CACHE TON NU!, undated (Moulin-Rouge, Paris)--Portfolio No. 34". B. J. Simmons & Co.: An Inventory of Its Costume Design Records. Harry Ransom Center. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

• "De la Belle Époque aux Années folles : le Paris de la couleur". Beaux Arts (in French). 4 November 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

• Monier, Noël (28 May 2022). "L'été trop chaud de 1914". Le 18e du mois (in French). Retrieved 28 May 2022.

• "Paris – Le Moulin Rouge". Musée Carnavalet. Paris Musées. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

• "Moulin Rouge". Le Figaro. Gallica. 20 May 1914. p. 5. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

• "Moulin Rouge". Le Bonnet rouge. Gallica. 24 July 1914. Retrieved 28 May 2022. - ^ "The big periods of the Moulin Rouge – PARISCityVISION". pariscityvision.com. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Underneath a Harlem moon : the Harlem to Paris years of Adelaide Hall | WorldCat.org". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Jaques Habas, Les secrets du moulin rouge, 2010

- ^ Emotion in Motion: Tourism, Affect and Transformation, Dr David Picard, Professor Mike Robinson, Ashgate Publishing, 28 November 2012

- ^ Compare 'Für Volk and Führer: The Memoir of a Veteran of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, Erwin Bartmann, Helion and Company, 19 October 2013'

- ^ a b c "Jacki Clerico". The Daily Telegraph. London. 18 January 2013. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ Jacques Pessis et Jacques Crépineau, The Moulin Rouge, October 2002

- ^ "Doris Haug, maîtresse de ballet du Moulin Rouge, est morte". Le Monde. 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Blades of Paris landmark Moulin Rouge windmill collapse". France 24. 25 April 2024.

- ^ "Iconic Paris cabaret club Moulin Rouge has its windmill back after structure collapse in April". Australia: ABC News. 6 July 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ https://m.independent.ie/opinion/comment/mary-kenny-paris-may-have-changed-but-2024-olympics-later-this-month-will-no-doubt-show-off-its-modern-charm/a970877267.html

External links

[edit]- Moulin Rouge official website in English

- Moulin Rouge official website in French

- Moulin Rouge – 42 Early Postcards at CPArama

- La danseuse du Moulin leshumanites Art+CultureDéveloppement

- História do Moulin Rouge

- Moulin Rouge in Times Square – New York Post

- Les 125 ans du Moulin Rouge – Radio France Internationale

![Zidler's assistant and Moulin-Rouge manager, Tremolada, pointing at Jules Chéret's 1889 poster, Bal du Moulin Rouge with Toulouse-Lautrec, Place Blanche, Paris, 1892[6]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Henri-de-Toulouse-Lautrec-with-Tremolada-standing-next-to-Jules-Cherets-1889-poster.png/211px-Henri-de-Toulouse-Lautrec-with-Tremolada-standing-next-to-Jules-Cherets-1889-poster.png)

![Moulin Rouge, la revue Cache Ton Nu !, 24 June 1914, by Stéphane Passet[8]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ef/Le_Moulin_Rouge%2C_Boulevard_de_Clichy%2C_Paris.jpg/194px-Le_Moulin_Rouge%2C_Boulevard_de_Clichy%2C_Paris.jpg)