Andrew Johnson and slavery

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 16th Vice President of the United States 17th President of the United States Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns Post-presidency Family  |

||

Andrew Johnson, who became the 17th U.S. president following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was one of the last U.S. Presidents to personally own slaves.[a] Johnson also oversaw the first years of the Reconstruction era as the head of the executive branch of the U.S. government. This professional obligation clashed with Johnson's long-held personal resentments: "Johnson's attitudes showed much consistency. All of his life he held deep-seated Jacksonian convictions along with prejudices against blacks, sectionalists, and the wealthy."[2] Johnson's engagement with Southern Unionism and Abraham Lincoln is summarized by his statement, "Damn the negroes; I am fighting these traitorous aristocrats, their masters!"[2]

According to Reconstruction historian Manisha Sinha, Johnson is remembered today for making white supremacy the overriding principle of his presidency through "his obdurate opposition to Reconstruction, the project to establish an interracial democracy in the United States after the destruction of slavery. He wanted to prevent, as he put it, the 'Africanization' of the country. Under the guise of strict constructionism, states' rights and opposition to big government, previously deployed by Southern slaveholders to defend slavery, Johnson vetoed all federal laws intended to protect former slaves from racial terror and from the Black Codes passed in the old Confederate states. This reduced African-Americans to a state of semi-servitude. Johnson peddled the racist myth that Southern whites were victimized by black emancipation and citizenship, which became an article of faith among Lost Cause proponents in the postwar South."[3]

In 1935, W. E. B. DuBois included an essay called "Transubstantiation of a Poor White" in his book Black Reconstruction in America. The topic was Johnson's Presidential Reconstruction, about which DuBois wrote: "Andrew Johnson could not include Negroes in any conceivable democracy. He tried to, but as a poor white, steeped in the limitations, prejudices, and ambitions of his social class, he could not; and this is the key to his career...For [the future of the] Negroes...he had nothing...except the bare possibility that, if given freedom, they might continue to exist and not die out."[4]

Personal ownership of slaves

[edit]Andrew Johnson typically said he owned between eight and 10 slaves, although the exact number is "surprisingly difficult to determine."[5] Eight people enslaved by Johnson are listed below; Liz, Florence, and William Johnson were born enslaved. Additional people enslaved by Johnson may be Sam Johnson's wife Margaret and their first three children, Dora, Robert, and Hattie, although their inclusion from a legal standpoint is entirely speculative, as the documentary record of Johnson's slave holdings is scant.[6] Other possible candidates are an unnamed child who may have been born to Dolly between Florence and William Andrew but who died young,[6] and possibly the wife of Henry Brown.[7]

When meeting with Frederick Douglass and other African-American leaders about the prospects for black male suffrage, Andrew Johnson's counterargument to black empowerment was a feigned victimhood. He told the group of visitors: "'I might say, however, that practically, so far as my connection with slaves has gone, I have been their slave instead of their being mine. Some have even followed me here, while others are occupying and enjoying my property with my consent.'"[8] Similarly, in March 1869, shortly after the end of his term in the White House, a newspaperman from Cincinnati found the ex-president at his home in Greeneville and conducted an interview. When asked about slavery, Johnson's reply was rich in me, my, and I statements, as was typical for him:[9] "I never bought but two or three slaves in my life, and I never sold one. The fact is [laughs] I was always more of a slave than any I owned. Slavery existed here among us, and those that I bought I bought because they wanted me to."[10] The most charitable possible interpretation of this statement, which implies a number of shocking presumptions, is that on some level Johnson understood that his slaves had substantially more character than he himself, a man who has been described as "all in all one of the most unlovable characters in U.S. presidential history,"[9] and "in some respects...the most pitiful figure of American history. A man who, despite great power and great ideas, became a puppet, played upon by mighty fingers and selfish, subtle minds; groping, self-made, unlettered and alone; drunk, not so much with liquor, as with the heady wine of sudden and accidental success."[4]

| Image | Name | Slave name | Purchase date | Purchase price | Freedom date | Born | Died | Family | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sam Johnson | Sam | 1842-11-29 | US$549 (equivalent to $17,333 in 2023) | 1863-08-08 | 1835 | after 1883 | Married, children | Emancipation Day traditions |

|

Dolly Johnson | Dolly | 1843-01-02 | US$500 (equivalent to $16,350 in 2023) | 1863-08-08 | 1825–1830 (est.) | after 1886 | Married, children | Emancipation Day traditions |

| Elizabeth Johnson Forby | Liz | Born enslaved under U.S. law because Johnson owned her mother | 1863-08-08 | 1846-03 | 1905-10-03 | Married, children | |||

|

Florence Johnson Smith | Florence | Born enslaved under U.S. law because Johnson owned her mother | 1863-08-08 | 1850-05 | 1920-09-20 | Married, children; she was survived by her son Edgar Smith;[11] | Worked as a maid at the White House during Johnson's presidency; died at Knoxville[6][12] | |

|

William Andrew Johnson | William Andrew | Born enslaved under U.S. law because Johnson owned her mother | 1863-08-08 | 1858 | 1943 | No spouse, no children | ||

| Henry Brown | Unknown, Henry is implied or presumed to have been a former slave, and has likely been historically conflated with Henry Johnson;[13] his exact legal status before the Civil War is unknown | Unknown | 1866-10-25 | Married | Worked at the White House during Andrew Johnson's presidency, and died there of cholera; had previously been a family servant for a long time[7] | ||||

| Henry Johnson | 1857-05-06 | US$1,050 (equivalent to $34,335 in 2023) | 1863-08-08 | about 1844 | 1890 | Unknown | Worked at the White House during Andrew Johnson's presidency, later worked at the post office; died at Knoxville[6] | ||

| Bill | Unknown | Unknown | 1863-08-08 | Married, children | Robert W. Winston, an early 20th century biographer, describes Bill as a "manservant" whose wife worked as the Johnson family cook[14][b] |

Paternity of Dolly Johnson's children

[edit]

Since the late 20th century historians have begun to speculate or insinuate that Andrew Johnson may have been the father of two, if not all three, of Dolly Johnson's children.[8][15][16][17][18][19][20] Dolly was enslaved by Johnson from 1843 until 1863.[8] Robert Johnson, Andrew Johnson's second-born son, was listed as father on William Andrew Johnson's death certificate in 1943.[21] There is no concrete evidence either proving or disproving paternity, and there have been no suggested alternate candidates over the last 175 years.[8] The National Park Service, which operates the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, notes "questionable paternity,"[22] and dedicates a page on their website to "Dolly's Children" but goes no further.[23] The father of Dolly Johnson's children could have been "anybody in Greeneville" and yet the relationship between the white and black Johnsons led "Tennessee whites to speculate that Andrew Johnson maintained a 'colored concubine.'"[24] Hints that the black Johnsons and the white Johnsons had an unusually close relationship include various combinations of them sharing households for years/decades after slavery ended, multiple cases of duplicated names amongst the children and grandchildren, Dolly being the recipient of furniture and household goods from the family, the inclusion of William Andrew Johnson in family-organized events honoring Johnson well into the mid-20th century, an account of Andrew Johnson paying for Florence to go to cooking school, the fact that Mary left Liz property in her will, and the fact that after Johnson died intestate his widow Eliza made that certain that Dolly could keep her house, etc.[25]

Interestingly, writes historian Annette Gordon-Reed:

[Johnson] fixated on the 'problem' of interracial sex. In fact, he believed that slavery promoted it because it brought blacks and whites into such intimate and daily contact with one another. In the days when the writing was on the wall, and he knew that slavery would die at the hands of the Civil War, Johnson adopted an antislavery stance and began to denounce the institution. All his speeches on the subject 'dwell almost obsessively on racial miscegenation as the institution's main evil.'...the slaveholding Johnson may have used all this hard talk against racial mixture as a cover for his own circumstances. He would not have been the first, or the last, southern white man to travel this tortured psychological route."[17]

If Johnson did have a shadow family with Dolly while hypocritically upholding a race-based caste system, it would have put him in the company of U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, Supreme Court Justice John Catron, sexual-predator U.S. Senator James Henry Hammond, and in the 20th century, U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond.[26] Johnson's possibly having fathered several multiracial children would have been part of a widespread "racial and sexual double standard...in the slaveholding states [that] gave elite white men a free pass for their sexual relationships with black women, as long as the men neither flaunted nor legitimated such unions."[26] American national leaders in less-hypocritical interracial relationships included U.S. Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson[27] and most likely Thaddeus Stevens (chair of the House Ways and Means committee and one of President Johnson's fiercest Congressional opponents).[28] Andrew Johnson lectured newly emancipated blacks on the necessity of avoiding "licentiousness" and the importance of learning the "laws of marriage,"[25] but, hypocritically, he himself may not have followed those laws. In addition to suspicions about his sexual exploitation of Dolly, he was accused twice in separate sworn testimonies of being familiar with sex workers;[29][30] in 1872, he was accused of seducing his neighbor's wife;[31] and he was posthumously described as the source of a "canker" in his wife's heart "fed or created, as the gossips have said, by the marital infidelity of her graceless lord."[32] In 1856 a Knoxville newspaper argued, "Honor conferred upon him is like a jewel put into the nose of a hog—it can escape no possible defilement."[33]

Martha Johnson Patterson Bartlett told interviewers about her father selectively burning letters prior to donating Andrew Johnson's correspondence to the Library of Congress. Bartlett commented, "...things that he thought was nobody's business, he'd burn them. And I'm glad he did. And here are some of these historians who are grabbers and like to feature that stuff – the fire has consumed them! And I'm glad of it. It's family. Private!" Researchers can only speculate but not know that "perhaps intimate letters between family members revealed the identity(ies) of the father of Dolly’s offspring."[34]

Emancipation Day

[edit]

According to family and historical records, Andrew Johnson freed his personal slaves on August 8, 1863, a date that falls between Abraham Lincoln's January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, from which Tennessee was exempted, and mass emancipation in Tennessee which occurred on October 24, 1864, by declaration of military governor Johnson.[10][36] A new Tennessee constitution abolished slavery in the state as of February 22, 1865.[36] The Thirteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified in December 1865.[37] According to University of Virginia history professor Elizabeth Maron, "Fearing that emancipation by federal edict would alienate Tennessee's slaveholding Unionists, Johnson urged that the state be exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, so he could promote the issue from the inside: in August 1863, Johnson freed his own slaves, seeking to set an example for his fellow Tennesseans."[38]

The August 8 date eventually became known as Freedom Day in Tennessee, and was also eventually celebrated in some neighboring communities in Kentucky, Missouri, and southern Illinois.[20] Andrew Johnson himself attended a Freedom Day celebration organized by Sam Johnson in 1871.[6][39] For the many decades between emancipation and desegregation, the annual August 8 picnic was the only day of the year that blacks were allowed to be in Knoxville's Chilhowee Park.[37] In 1938, William Andrew Johnson, then 80 years old, spoke at a Tennessee Emancipation Day celebration at Chilhowee Park.[40]

Johnson is one of the last surviving slaves in this section. January 1 was designated as Emancipation day but Andrew Johnson freed his slaves August 8 and Negroes of East Tennessee have always observed that date as Emancipation day. The celebration this year has been changed to August 9 because August 8 is on Sunday.

— The Knoxville Journal, August 8, 1938[40]

From Moses to Pharaoh

[edit]Prior to the summer of 1863, Johnson had staunchly opposed general emancipation, but beginning in August of that year, he made a sharp heel-turn in favor of freeing the slaves. Historians find that "his opinion changed with little warning. Flattery by Northern politicians during a tour of Northern states may have swayed him; loyalty to Lincoln's war policy and ambitions to serve on a presidential ticket in 1864 assuredly influenced him as well."[41]

Andrew Johnson made what is remembered as the Moses speech, on October 24, 1864, in Nashville, Tennessee,[43] when he was military governor of Tennessee and a candidate for vice president on the Lincoln Unionist ticket. "Before an audience of ten thousand colored men...amidst cheers which shook the sky," Johnson proclaimed that he would act for their benefit and advancement as a race now that the slaves of the United States had been emancipated.[44]

I will indeed be your Moses, and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage, to a fairer future of liberty and peace. I speak, too, as a citizen of Tennessee. I am here on my own soil, and here I mean to stay and fight this great battle of truth and justice to a triumphant end. Rebellion and slavery shall, by God's good help, no longer pollute our State. Loyal men, whether white or black, shall alone control her destinies: and when this strife in which we are all engaged is past, I trust, I know, we shall have a better state of things, and shall all rejoice that honest labor reaps the fruit of its own industry, and that every man has a fair chance in the race of life.

— Andrew Johnson

Johnson refers to the Biblical figure Moses from the book of Exodus, who led the enslaved Jews of ancient Egypt out of bondage with the aid of his god, who parted the Red Sea so that they might pass, and then released the waters upon their pursuers.

Johnson betrayed those who trusted in this campaign promise. As a 1989 book review put it, "Nowhere was Johnson's duplicitous nature more cruelly evident than on questions of race."[45] Per historian Robert S. Levine, "...Johnson worked to undermine the Freedmen's Bureau, to dismantle other Reconstruction initiatives, and to prevent African Americans from attaining equal rights through federal legislation."[46] The betrayal, which contributed to the failure of Reconstruction and another 100 years of racial oppression,[46] continues to be a central focus of historians, but was recognized and criticized in his own time.[47] Johnson's turn from staunch Unionist to Confederate apologist, and his centrality to the diminishment of the goals of Reconstruction, was also gratefully lauded by his fellow white supremacists of the legacy South:[48]

To show the great change effected in Mr. Johnson, no further proof is needed than extracts from Southern papers. The Memphis Argus, one of the most uncompromising rebel sheets published, said in 1862:

"We should to like to see Andrew Johnson's lying tongue torn from his foul mouth, and his miserable carcass thrown to the dogs, or hung on a gibbet as high as Haman to feed the carrion buzzards."

The same paper, edited by the same man, says in 1866:

"The iron firmness, the undismayed soul of a single man (Andrew Johnson) is all that stands between us and the fatal vortex of anarchy and resultant despotism which has engulphed the lives and fortunes of many millions before us.—Let us rally to the side of that man, determined to save or perish with the Republic."[48]

In a report about Johnson's supposed tears over superficial gestures of national comity at the pro-Johnson 1866 National Union Convention in Philadelphia: "There is good reason to believe, that when Miss Columbia, in imitation of Miss Pharaoh, fished among the bulrushes and slimy waters of Southern plebeianism for a little Moses, she slung out a young crocodile instead. He is a crocodile by nature, although he calls himself Moses. He craunches and gulps down whatever stands in his way, without any signs of mercy, yet is always prepared to shed tears to order."[49] The image that Johnson provided of himself-as-Moses was sufficiently rich that it continues to be applied with grim irony to present day.[50][51]

Congressmen, including U.S. Senator Sumner, referenced the Moses speech during the Andrew Johnson impeachment hearings:[52]

Andrew Johnson is the impersonation of the tyrannical slave power. In him it lives again. He is the lineal successor of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis; and he gathers about him the same supporters. Original partisans of slavery north and south; habitual compromisers of great principles; maligners of the Declaration of Independence; politicians without heart; lawyers, for whom a technicality is everything, and a promiscuous company who at every stage of the battle have set their faces against equal rights; these are his allies. It is the old troop of slavery, with a few recruits, ready as of old for violence...With the President at their head, they are now entrenched in the Executive Mansion. Not to dislodge them is to leave the country a prey to one of the most hateful tyrannies of history...Not a month, not a week, not day should be lost. The safety of the Republic requires action at once. The lives of innocent men must be rescued from sacrifice. I would not in this judgment depart from that moderation which belongs to the occasion; but God forbid that, when called to deal with so great an offender, should affect a coldness which I cannot feel. Slavery has been our worst enemy, assailing all, murdering our children, filling our homes with mourning, and darkening the land with tragedy; and now it rears its crest anew, with Andrew Johnson as its representative. Through him assumes once more to rule the Republic and to impose its cruel law. The enormity of his conduct is aggravated by his bare faced treachery. He once declared himself the Moses of the colored race. Behold him now the Pharaoh.

— U.S. Senator Charles Sumner (R-Massachusetts), written statement regarding impeachment vote

Andrew Johnson and civil rights

[edit]

Johnson vetoed several pieces of Congressional legislation that were designed to improve the humanitarian conditions of recently emancipated slaves and/or provide black men with rights that had previously been held only by white men.[25] Johnson would typically "claim that the future status of freed people was not an issue of racism, but an issue of constitutionality."[25] He thus opposed almost all aspects of Congressional Reconstruction, including the Fourteenth Amendment.[25] He argued that improvements in the status of black Americans would only be legitimate if passed on the state, rather than federal level,[25] but he also vetoed the D.C. Franchise Bill, and the District of Columbia is constitutionally defined as the jurisdiction of no state but solely of the U.S. Congress.[17] In American Heritage magazine, historian David Herbert Donald retold a colorful story about Johnson's use of whataboutism in discussions with Sumner about the necessity of the Freedmen's Bureau:[53]

The Senator was depressed by Johnson's 'prejudice, ignorance, and perversity' on the Negro suffrage issue. Far from listening amiably to Sumner's argument that the South was still torn by violence and not yet ready tor readmission, Johnson attacked him with cheap analogies. 'Are there no murders in Massachusetts?' the President asked.

'Unhappily yes,' Sumner replied, 'sometimes.'

'Are there no assaults in Boston? Do not men there sometimes knock each other down, so that the police is obliged to interfere?'

'Unhappily yes.'

'Would you consent that Massachusetts, on this account, should be excluded from Congress?' Johnson triumphantly queried. In the excitement of the argument, the President unconsciously used Sumner's hat, which the Senator had placed on the floor beside his chair, as a spittoon![53]

| Veto date | Bill | |

|---|---|---|

| February 19, 1866 | Freedmen's Bureau Bill | During his Swing Around the Circle Tour he complained about "the cost of the Freedmen's Bureau and of re-enslavement of the Negro by its agents"[54] |

| March 27, 1866 | Civil Rights Bill | |

| July 16, 1866 | Freedmen's Bureau Bill | |

| January 5, 1867 | District of Columbia Suffrage Act | |

| March 2, 1867 | First Military Reconstruction Act (see Reconstruction Acts) | |

| March 23, 1867 | Second Military Reconstruction Act | |

| July 19, 1867 | Third Military Reconstruction Act | |

| July 25, 1868 | Freedmen's Bureau Bill |

Previous condition of servitude

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

Andrew Johnson was probably experientially closer to chattel slavery than any other U.S. president. At age 10 he was indentured by his mother and stepfather to a tailor, to whom he was legally bound until age 21. He was required to work incessantly, and a traditional education was out of the question. He ran away at age 15. His master, James Selby, put a "runaway servant" ad in the newspaper. White supremacist[55] writer, magazine editor, and librarian/archivist John Trotwood Moore described teenage Johnson in a 1929 Saturday Evening Post article as a "slave-bound boy."[56] One study of presidential rhetorical styles argued, "no amount of success could fully compensate for the needs left from his traumatic childhood."[57]

See also

[edit]- List of United States presidential vetoes § Andrew Johnson

- Voting rights in the United States

- Bibliography of Andrew Johnson

- Presidency of Andrew Johnson

- Reconstruction era

- Freedmen's Bureau bills

- Freedmen massacres

- Reconstruction Amendments

- Nadir of American race relations

- Andrew Johnson alcoholism debate

- African Americans in Tennessee

- Woodrow Wilson and race

Notes

[edit]References

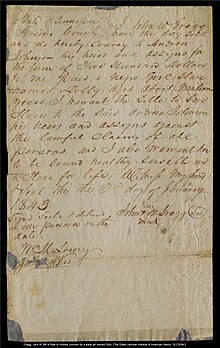

[edit]- ^ "Bill of sale to Andrew Johnson for a slave girl named Dolly". Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Greene County, Tenn. 1843. GLC02041. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- ^ a b Cimprich, John (1980). "Military Governor Johnson and Tennessee Blacks, 1862-65". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 39 (4): 459–470. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42626128.

- ^ Sinha, Manisha (November 29, 2019). "Donald Trump, Meet Your Precursor". Opinion. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ a b DuBois, W.E.B. (1935). "Transubstantiation of a Poor White". Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1888. New York: Russell. pp. 242–244 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bowen, David Warren (1989). Andrew Johnson and the Negro. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 51–57. ISBN 978-0-87049-584-7. LCCN 88009668. OCLC 17764213.

- ^ a b c d e "Slaves of Andrew Johnson". Andrew Johnson National Historic Site (nps.gov). Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ^ a b "Washington: By Telegraph to the Tribune". New York Tribune. October 29, 1866. p. 10. Retrieved 2023-06-26 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c d Fling, Sarah (2020). "The Formerly Enslaved Households of President Andrew Johnson". WHHA (en-US). Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ a b Browne, Stephen Howard (2008). "Andrew Johnson and the Politics of Character". In Medhurst, Martin J. (ed.). Before the Rhetorical Presidency. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 194–212. ISBN 978-1-60344-626-6. Retrieved 2023-07-30 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ a b "Interviewed: A Confab with Andrew Johnson, What the ex-President Says About Matters and Things". Republican Banner. March 28, 1869. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Negro Woman, Served as White House Maid, Dies Here at Age of 80 Years". The Journal and Tribune. September 16, 1920. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ "Johnson's Housemaid". Chattanooga Daily Times. September 16, 1920. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ Holland, Jesse J. (January 2016). The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-4930-2419-3.

- ^ Winston, Robert W. (1928). Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot. New York: Henry Holt & Company. LCCN 28007534. OCLC 475518. OL 6712742M – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Boren, Rance A. (September 2022). "A case of neglect". Cortex. 154: 254–258. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2022.06.003. ISSN 0010-9452. PMID 35810499. S2CID 249650951.

- ^ Wineapple, Brenda (2020). The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation. Random House Publishing Group. p. 52. ISBN 9780812987911 – via Libby.

- ^ a b c Gordon-Reed, Annette (2011). Andrew Johnson. The American Presidents Series. New York: Times Books/Henry Holt. pp. 16, 41–42, 128–129. ISBN 978-0-8050-6948-8. LCCN 2010032595. OCLC 154806758.

- ^ Holland, Jesse J. (2016). The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press. pp. 193–201. ISBN 978-1-4930-0846-9. LCCN 2015034010. OCLC 926105956.

- ^ Bowen, David Warren (2005) [1976, 1989]. "Chapter 3: The Defender of Slavery". Andrew Johnson and the Negro. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-87049-584-7. LCCN 88009668. OCLC 17764213. Originally published as a thesis: ProQuest 7710753.

- ^ a b Miller, Zachary A. (August 2022). False Idol: The Memory of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction in Greeneville, Tennessee 1869-2022 (Master of Arts thesis). Eastern Tennessee State University. p. 117. Paper 4096.

- ^ "William A. Johnson, 16 May 1943; Death, Knox, Tennessee, United States", Tennessee Deaths, 1914-1966, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville – via FamilySearch

- ^ Greeneville, Mailing Address: Andrew Johnson National Historic Site 121 Monument Ave; Us, TN 37743 Phone: 423 638-3551 Contact. "Slaves of Andrew Johnson - Andrew Johnson National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Greeneville, Mailing Address: Andrew Johnson National Historic Site 121 Monument Ave; Us, TN 37743 Phone: 423 638-3551 Contact. "Dolly's Children - Andrew Johnson National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Egerton, Douglas R. (2014). The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America's Most Progressive Era. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-60819-566-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R.; Zuczek, Richard (June 22, 2001). Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 32–35 (Blacks, Johnson's attitude toward), 269–270 (Slaves, owned by Johnson), 305 (vetoes). ISBN 978-1-57607-030-7.

- ^ a b Clinton, Catherine (2010), Brooten, Bernadette J. (ed.), "Breaking the Silence: Sexual Hypocrisies from Thomas Jefferson to Strom Thurmond", Beyond Slavery, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 213–228, doi:10.1057/9780230113893_13, ISBN 978-0-230-10017-6, retrieved 2023-08-01

- ^ Potter, Leslie (February 20, 2020). "The Lost Story of Julia Chinn > KET". KET. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ "Thaddeus Stevens, Relationship with Lydia Hamilton Smith (Trefousse, 1997) | House Divided". hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ "The Impeachment Case". The Pittsburgh Daily Commercial. July 27, 1867. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ "Lucy Cobb & Lafayette Baker". Semi-Weekly Wisconsin. November 30, 1867. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ "The Greenville, Tenn. Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson". New York Daily Herald. May 29, 1872. p. 7. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ "A. Johnson, Tailor - The Curtain Raises and Delusions as to His Real Character Dispelled". Public Ledger. August 17, 1891. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ "Andrew Johnson—Still in the Gutter". The Knoxville Register. October 9, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ Wiley, Dawn (August 2, 2023). "Eliza McCardle Johnson: Conflicting Memories and Vanishing Evidence of the Enslaved Past". WHHA (en-US). Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ "Celebration at Greeneville [Sam Johnson and Emancipation Day addressed by ex-President Johnson]". Knoxville Daily Chronicle. August 9, 1871. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-06-24 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Emancipation Proclamation in Tennessee". tnmuseum.org. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ a b Brown, Fred (June 24, 2023). "Significance of this date recorded mainly in hearts; Researchers seek more (Part 1 of 1)". Local section, Appalachian Journal column. The Knoxville News-Sentinel. p. B1. Page image 22. Retrieved 2023-06-24 – via Newspapers.com. & "Journal (Part 2 of 2)". August 10, 2003. p. B2.

- ^ Varon, Elizabeth (October 4, 2016). "Andrew Johnson: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 2023-03-21. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ^ "Knoxville Daily Chronicle 09 Aug 1871, page Page 4". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ a b "William Andrew Johnson speaks at August 8th Event, 1937". The Knoxville Journal. August 6, 1937. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-05-17.

- ^ Astor, Aaron (August 9, 2013). "When Andrew Johnson Freed His Slaves". Opinionator. The New York Times. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ Nast, Thomas (April 14, 1866). "Untitled caricature collage". Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. X, no. 485. p. 232 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ ""The Moses of the Colored Men" Speech". Andrew Johnson National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "The Modern Moses". Cleveland Daily Leader. February 26, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "Book review of Trefousse biography of Andrew Johnson". American Heritage. Vol. 40, no. 5. July–August 1989. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ a b Levine, Robert S. (2021). The Failed Promise: Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass, and the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 208. ISBN 9781324004769. LCCN 2021005132.

- ^ Varon, Elizabeth R. (March 3, 2016). "Andrew Johnson and the Legacy of the Civil War". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.11. ISBN 978-0-19-932917-5. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ a b "President Johnson". The Baltimore County Union, The Towson News. September 1, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ "Tears". White Cloud Kansas Chief. August 30, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. "He Was No Moses". ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ Rothera, Evan (January 27, 2020). ""Moses in Retirement": Andrew Johnson, 1869-1876". The Gettysburg Historical Journal. 7 (1). ISSN 2327-3917.

- ^ Fleming, Walter Lynwood (1906). Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational & Industrial, 1865 to the Present Time. A.H. Clark Company. p. 471.

- ^ a b "Why They Impeached Andrew Johnson". AMERICAN HERITAGE. Retrieved 2024-01-05.

- ^ Phifer, Gregg (1952). "Andrew Johnson Argues a Case". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 11 (2): 148–170. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42621106.

- ^ Bailey, Fred Arthur (1999). "John Trotwood Moore and the Patrician Cult of the New South". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 58 (1): 16–33. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42627447.

- ^ Moore, John Trotwood (March 30, 1929). "Andrew Johnson—The Rail-Splitter's Running Mate". Saturday Evening Post. Vol. 201, no. 39. pp. 24–25, 162, 165, 166, 169.

- ^ Barber, James D. (1968). "Adult Identity and Presidential Style: The Rhetorical Emphasis". Daedalus. 97 (3): 938–968. ISSN 0011-5266. JSTOR 20023846.