Milltown Cemetery

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

| Milltown Cemetery | |

|---|---|

The entrance to Milltown Cemetery: 546 Falls Road | |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1869 |

| Location | West Belfast |

| Coordinates | 54°34′57″N 5°58′25″W / 54.58250°N 5.97361°W |

| Style | Primarily Irish Roman Catholic funerary art |

| Size | 55 acres (220,000 m2) |

| No. of graves | 50,000 |

| No. of interments | 200,000 |

| Find a Grave | Milltown Cemetery |

Milltown Cemetery (Irish: Reilig Bhaile an Mhuilinn) is a large cemetery in west Belfast, Northern Ireland. It lies within the townland of Ballymurphy, between Falls Road and the M1 motorway.

History

[edit]Milltown Cemetery opened in 1869 as part of the broader provision of services for the city of Belfast's expanding Catholic population. [1] The cemetery was an important development in the episcopal reign of Bishop Patrick Dorrian of the Diocese of Down and Connor. [2]

Although the cemetery's history and story is often presented as a nationalist and Irish Republican site, in fact the overwhelming majority of the approximately 200,000 of Belfast dead who are buried there were ordinary Catholics, many in unmarked graves.[3]

Within the cemetery there are three large sections of open space, each about the size of a football pitch, designated as "poor ground". Over 80,000 people are buried in the cemetery's poor grounds, many of whom died in the flu pandemic of 1919.[3] Since 2007, the 55-acre (220,000 m2) cemetery has undergone extensive work, reversing years of neglect.[4]

Republicanism

[edit]The cemetery has, for some, become synonymous with Irish republicanism. Irish Republican Army prisoner Bobby Sands, who died on hunger strike on 5 May 1981, is buried in the cemetery. Fellow hunger-strikers, Kieran Doherty, Joe McDonnell and Pat McGeown (who died of a heart attack in 1996) are also buried there. In total, 77 IRA volunteers are buried in what is known as the 'New Republican Plot', a further 34 volunteers are buried in what is known as the County Antrim Memorial Plot and which was used between 1969 and 1972.[5] Throughout the cemetery, many more IRA volunteers are buried in family graves. These include Tom Williams, who was executed in Crumlin Road Prison on 2 September 1942. Williams' body lay in a prison grave until January 2000, when a campaign, by the National Graves Association, Belfast, to have his remains re-interred in Milltown was successful.[6] Members of the INLA, IPLO and Workers' Party are also buried there.[3]

The cemetery was the scene of the Milltown Cemetery attack on 16 March 1988, when loyalist Michael Stone attacked a funeral, killing three mourners as IRA volunteers Dan McCann, Seán Savage and Mairéad Farrell, were being buried.[citation needed] All three had been killed by members of the SAS at Gibraltar during Operation Flavius.[citation needed]

Graves

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2016) |

- Harbinson Plot

- William Harbinson died while interned in Belfast Prison and was buried at Portmore, Ballinderry. A Celtic cross was erected to his memory, and that of other republicans who were imprisoned in County Antrim jails, in Milltown cemetery in 1912. This plot contains the remains of 5 IRA volunteers:

- Joe McKelvey, Liam Mellows, Dick Barrett, and Rory O'Connor were captured when Free State forces attacked the Four Courts in Dublin. Without charge or trial, on 8 December 1922, they were executed by firing squad. In 1924, McKelvey was re-interred in Milltown.

- Sean McCartney was shot dead while engaging in paramilitary activities on 8 May 1921 in the Lappinduff Mountains, County Cavan. He was a member of a Belfast Flying Column which operated there.

- Terence Perry, in 1939, as part of the IRA's Expeditionary Force, volunteered for paramilitary activities in England. Captured, he was imprisoned in Parkhurst Prison, where he died on 7 July 1942.

- Sean Gaffney, an IRA volunteer was imprisoned on the prison ship HMS Al Rawdah, moored at Strangford Lough. On 18 November 1940, he died while still in prison.

- Seamus "Rocky" Burns, while interned, escaped from Derry jail. He was in Belfast when he was shot by RUC personnel in Castle Street. He died on 12 February 1944.[7]

- County Antrim Memorial Plot

- Unveiled on the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, the plot honours the county's republican dead.[8] 34 IRA volunteers who died while involved in paramilitary activity during the late 1960s and early 1970s are buried there.

- New Republican Plot

- In 1972, the National Graves Association purchased the ground which would become the New Republican Plot. It has space for 46 graves, each to accommodate four burials (allowing for a total of 184 coffins to be buried). The first burials here took place in July of that year. This plot contains the remains of 77 IRA Volunteers who have died while engaging in paramilitary activities or as a result of imprisonment or assassination, not only in Belfast but those killed as far away as Gibraltar. Here are buried those volunteers who died as a result of hunger striking.[7]

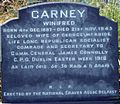

- Winifred Carney Grave

Winifred Carney, a lifelong socialist (died 21 November 1943) was a member of the Irish Citizen Army and Cumann na mBan. In 1916 during the Easter Rising she was secretary to Commadante James Connolly and the last woman to leave the G.P.O.[7]

- Sean McCaughey Grave

- INLA Plot

- The INLA Plot contains the remains of ten members of the Irish National Liberation Army

Priest's Row

[edit]Another significant section of the cemetery, facing onto the Andersonstown Road is the plot where many senior Catholic clerics, important educational, social and cultural figures in post-Partition Northern Ireland, are buried. Many of the graves are adorned with high Celtic crosses. There are over two dozen priests of the Diocese of Down and Connor buried here almost all of them with strong pastoral and familial links to West Belfast. Among the most prominent are:

- Bishop Daniel Mageean

- Canon James Clenaghan, the grave inscription is entirely in Irish reflecting his cultural interests. Former President St. Malachy's College

- Canon Patrick Rogers D.Litt., MRIA, principal of Trench House/ St Joseph's College of Education, forerunner of St Mary's University College, Belfast

- Monsignor Dean Frank Kerr, PP St Malachy's Church, Belfast – brother of Fr Hugo Kerr, after whom Hugo St is named

- Rev John A MacLaverty, Adm St. Peter's Cathedral, Belfast died 1943 [9]

- Canon Patrick McGouran, PP Sacred Heart, Belfast – a nephew of Bishop Daniel Mageean and a former chaplain to those interned on HMS Argenta in 1923 while a teacher at St Malachy's College[10]

- Monsignor Arthur H Ryan, PP St. Brigid's, Belfast [11]

- Fr John McCaughan BCL, PP St Paul's Belfast, former President St. Malachy's College, died 1939

- An tAthair Roibeard Fullerton, who led the Gaelic League & Irish language revival across Ulster, inscription entirely in Irish [12]

- Monsignor Dean Gerard Montague DD, PP St Paul's Belfast, died 1994 [13]

War Graves

[edit]The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains and registers the graves within the cemetery of British Commonwealth service personnel, covering years 1914–21 and 1939–47. There are 102 World War I and 52 World War II graves, besides 10 foreign national servicemen. The focal point is a Cross of Sacrifice erected by the commission after World War I, near which stands a Screen Wall memorial listing those of that war whose graves could not be individually marked.[14]

Belfast Blitz Memorial

[edit]The Belfast Blitz occurred in the April and May 1941 when approximately 1,000 citizens of the city, known and unknown, perished. After the burials of those who could be identified the city authorities were left with human remains where positive identification was not possible.

It was decided to have two large 'en masse' burials, one at the City Cemetery and one at Milltown where 30 unknown people, who bore effects identifying them as Catholics, are buried. In 2012 the memorial was restored. [15]

Image gallery

[edit]- Notable graves

-

Harbinson Plot

-

County Antrim Memorial Plot

-

Grave of Winifred Carney, Socialist and combatant in GPO, Dublin 1916

-

Grave of Ned Trodden

-

Grave of volunteer Sean Martin

-

Grave of volunteer Sean Gaynor

-

Photograph taken prior to restoration work

-

Photograph of New Republican Plot

-

New Republican Plot. Plaque dedicated to the ten men who died on Hunger Strike in the H Blocks of Long Kesh in 1981

-

New Republican Plot. Plaque on the grave of volunteer Bobby Sands

-

Grave of IRA volunteers Dan McCann, Mairead Farrell and Sean Savage who were killed in Gibraltar in 1988

-

Grave of volunteer Kieran Doherty who died on Hunger strike in the H Blocks of Long Kesh in 1981

-

County Antrim Memorial Plot

-

County Antrim Memorial Plot

-

INLA Plot

-

Official IRA/Workers' Party Plot

-

Workers' Party Plot

-

Celtic Cross at the entrance of the cemetery dedicated to the first priests buried there

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.dib.ie/biography/dorrian-patrick-a2719# Archived 8 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL]

- ^ "Tread lightly as you pass St Patrick's". Archived from the original on 18 August 2024. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Cemetery Records

- ^ "Milltown Cemetery announces the Digitalisation of Burial Records". 11 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 August 2024. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ National Graves Association leaflet 'Milltown Cemetery'

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ a b c National Graves Association, Belfast

- ^ Antrim's Patriot Dead 1797–1953 by National Graves Association, Belfast, Pages 7 & 9

- ^ "History – St. Mary Star of the Sea, Killyleagh". Archived from the original on 4 August 2015.

- ^ Kleinrichert, Denise (2001). Republican Internment and the Prison Ship Argenta 1922. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9780716526834.

- ^ "Arthur Ryan 1897–1982" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2018 – via eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie.

- ^ "Tuilleadh tagairtí do dhaoine a bhuanuigh oidhreacht Ghaedhealach Chúige Uladh". Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ "The Irish Times, Tuesday, November 1, 1994, p. 4". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Cemetery Details". Cwgc.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Belfast Blitz's unknown victims remembered as restored gravestone is unveiled". Belfasttelegraph. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Hartley, Tom (2014). Milltown Cemetery: the history of Belfast, written in stone. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. ISBN 978-0-85640-925-7.