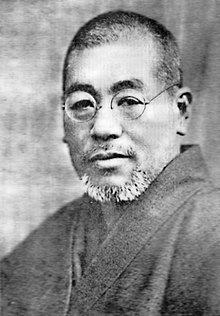

Mikao Usui

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Mikao Usui | |

|---|---|

臼井甕男 | |

| Born | 15 August 1865 Taniai (now called Miyama cho) (Gifu) |

| Died | 9 March 1926 (aged 60) Fukuyama (福山市) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation | Reiki Master |

| Known for | Reiki |

Mikao Usui (臼井甕男, 15 August 1865 – 9 March 1926, commonly Usui Mikao in Japanese) was the father of a form of energy medicine and spiritual practice known as Reiki,[1]: 108–10 [2][3][4][5][6] used as an alternative therapy for the treatment of physical, emotional, and mental diseases. According to the inscription on his memorial stone, Usui taught Reiki to over 2,000 people during his lifetime. Eleven of these students continued their training to reach the Shinpiden level, a level equivalent to the Western third degree, or Master level.[1]: 16

Early life, family and education

[edit]Usui was born on 15 August 1865[7] in the village of Taniai (now called Miyama cho) in the Yamagata district of the Gifu Prefecture, Japan, which is now located near present-day Nagoya.[8] Usui's father's common name was Uzaemon,[9] and his mother was from the Kawai family.[9] His brothers, Sanya and Kuniji, became a doctor and a policeman, respectively. He also had an older sister called Tsuru. Usui's ancestors were the once influential Chiba clan and were Hatamoto samurai. According to the inscription on his memorial, Tsunetane Chiba,[9] a military commander during the end of the Heian period and the start of the Kamakura period (1180–1230), was one of Usui's ancestors. In 1551, Toshitane Chiba conquered the city Usui and thereafter all family members acquired that name.[10] Usui was raised as a samurai from childhood, specifically in the martial arts techniques of aiki (合氣術).[11]

Although there are many stories extant in the United States that Mikao Usui earned a doctorate of theology at the theological seminary of the University of Chicago,[12] it is evident from further research that he never attended, let alone received any degree from the University of Chicago.[13]

Career and activities

[edit]As an adult, it is believed that he traveled to several Western countries, including the Americas, Europe, and China as a part of his continued study.[9] His studies included history, medicine, Buddhism, Christianity, psychology, and Taoism.[11][10][14]

It is believed that the aim of Usui's teachings was to provide a method for students to achieve connection with the "universal life force" energy that would help them in their self-development. What sets Usui's teachings apart from other hands-on healing methods is his use of reiju or attunement to remind students of their spiritual connection. It seems that all students of Usui received five principles to live by and those with a further interest in the teachings became dedicated students. There does not appear to have been a distinction between clients and students in the beginning though this may have changed at some point. People began coming to Usui Mikao possibly for different purposes – some for healing and others for the spiritual teachings.

Shugendō is a Japanese mountain ascetic shamanism, which incorporates Shinto and Buddhist practices.[15] The roles of Shugendō practitioners include offering religious services such as fortune telling, divination, channelling, prayer, ritual incantations and exorcism. Shugendo was often used by family clans to heal disease or to avoid misfortune.[11]

Claims of Reiki's Christian origins

[edit]Hawayo Takata, a Reiki Master under the tutelage of Chujiro Hayashi (林 忠次郎, 1880–1940), lied about Reiki's history of development to make Reiki more appealing to the West.[16] To this end she made a relation of Reiki with Jesus Christ and not with Buddhism. She also falsely presented Usui as the dean of a Christian school. While he had obtained the knowledge of Reiki from the Buddhist religious book Tantra of the Lightning Flash, Takata claimed that he had been inspired from the story of Jesus Christ, who had healed with the touch of his hand, and so had come to America to learn Reiki. She told this to spread Reiki among Christians too, believing it would otherwise be extinct[citation needed]. However, Reiki originated from Buddhism.[17] In reality, Takata charged people thousands of dollars for each Reiki degree, each degree being more expensive than the prior degree.

Activity in the 1920s

[edit]During the early 1920s, Usui did a 21-day practice on Mount Kurama called discipline of prayer and fasting, according to translator Hyakuten Inamoto. Common belief dictates that it was during these 21 days that Usui developed Reiki. As Mount Hiei is the main Tendai complex in Japan, and is very close to Kyoto, it has been surmised that Usui would also have practiced there if he had been a lay priest. This teaching included self-discipline, fasting and prayer.

In April of the 11th year of Taisho (1922 A.D.) he settled in Harajuku, Aoyama, Tokyo and set up the Gakkai to teach Reiki Ryoho and give treatments. Even outside of the building it was full of pairs of shoes of the visitors who had come from far and near.

— [who?]

In September of the 12th year (1923 A.D.) there was a great earthquake and a conflagration broke out. Everywhere there were groans of pains from the wounded. Sensei, feeling pity for them, went out every morning to go around the town, and he cured and saved an innumerable number of people.

— [who?]

Personal life and death

[edit]Usui married Sadako Suzuki, who bore children by the names of Fuji and Toshiko. Fuji (1908–1946) became a teacher at Tokyo University. Toshiko died at age 22 in 1935.

Usui died on 9 March 1926 of a stroke.

The family's ashes are buried at the grave site at the Saihō-ji Temple in Tokyo.[10]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Lübeck, Walter; Petter, Frank Arjava; Rand, William Lee (2001). The Spirit of Reiki: From Tradition to the Present. Lotus Press. ISBN 9780914955672.

- ^ Ellyard, Lawrence (2004). A Complete Guide to the Path and Practice of Reiki. Lotus Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780940985643.

- ^ McKenzie, Eleanor (1998). Healing Reiki (1st illustrated ed.). Ulysses Press. pp. 19, 42, 52. ISBN 9781569751626.

- ^ Lübeck, Walter (1996). Reiki – Way of the Heart. Lotus Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780941524919.

- ^ Boräng, Kajsa Krishni (1997). Principles of Reiki. Thorsons. p. 57.

- ^ Veltheim, John; Veltheim, Esther (1995). Reiki: The Science, Metaphysics and Philosophy. p. 72.

- ^ "臼井先生功徳之碑 原文". 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Rand, William L (2005). Reiki the Healing Touch: First and Second Degree Manual. Michigan, USA: Vision Publications. p. I-13. ISBN 1-886785-03-1.

- ^ a b c d Inscription on Usui's memorial

- ^ a b c "Reiki History – Usui Mikao". reiki.net.au. International House of Reiki. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Stiene, Bronwen; Stiene, Frans (2005). The Japanese Art of Reiki: A Practical Guide to Self-healing. Hampshire, UK: O Books. ISBN 1-905047-02-9.

- ^ Arnold, Larry E.; Nevius, Sandra (1985) [1982]. The Reiki handbook (2nd ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: PSI Press.

- ^ "History of Reiki". reiki.org. The International Center for Reiki Training. 15 October 2014.

- ^ Beckett, Don (2009). Reiki: the True Story: An Exploration of Usui Reiki. Berkeley, California: Frog Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58394-267-3.

- ^ "Shugendō". Tangorin.com Japanese Dictionary. Retrieved 27 April 2010 – via tangorin.com.

- ^ Rand, William L. (March 1998) [1991]. Reiki: The Healing Touch, First and Second Degree Manual (Expanded and Revised ed.). Michigan: Vision Publications. ISBN 1-886785-03-1.

- ^ Shah, Anuj K.; Becicka, Roman; Talen, Mary R.; Edberg, Deborah; Namboodiri, Sreela (2017). "Integrative Medicine and Mood, Emotions and Mental Health". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 44 (2). Elsevier BV: 281–304. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2017.02.003. ISSN 0095-4543.