Megatherium

| Megatherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| M. americanum skeleton, Natural History Museum, London | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Clade: | †Megatheria |

| Family: | †Megatheriidae |

| Subfamily: | †Megatheriinae |

| Genus: | †Megatherium Cuvier, 1796 |

| Type species | |

| †Megatherium americanum Cuvier, 1796

| |

| Subgenera | |

|

Megatherium

| |

| |

| Map showing the distribution of all Megatherium species in red, inferred from fossil finds | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

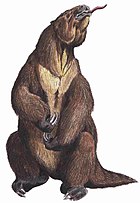

Megatherium (/mɛɡəˈθɪəriəm/ meg-ə-THEER-ee-əm; from Greek méga (μέγα) 'great' + theríon (θηρίον) 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene[1] through the end of the Late Pleistocene.[2] It is best known for the elephant-sized type species Megatherium americanum, primarily known from the Pampas, but ranging southwards to northernmost Patagonia and northwards to southern Bolivia during the late Middle Pleistocene and Late Pleistocene. Various other species belonging to the subgenus Pseudomegatherium ranging in size comparable to considerably smaller than M. americanum are known from the Andean region.

The first (holotype) specimen of Megatherium was discovered in 1787 on the bank of the Luján River in what is now northern Argentina. The specimen was then shipped to Spain the following year wherein it caught the attention of the French paleontologist Georges Cuvier, who named the animal in 1796 and was the first to determine, by means of comparative anatomy, that Megatherium was a giant sloth.

Megatherium is part of the sloth family Megatheriidae, which also includes the closely related and similarly giant Eremotherium, comparable in size to M. americanum, which was native to tropical South America, Central America and North America as far north as the southern United States.

Megatherium americanum is thought to have been a browser that fed on the foliage and twigs of trees and shrubs using a black rhinoceros–like prehensile upper lip. Despite its large body size, Megatherium americanum is widely thought to have been able to adopt a bipedal posture at least while standing, which allowed it to feed on high-growing leaves, as well as possibly to use its claws for defense.

Megatherium became extinct around 12,000 years ago as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event, simultaneously with the majority of other large mammals in the Americas. The extinctions followed the first arrival of humans in the Americas, and one and potentially multiple kill sites where M. americanum was slaughtered and butchered is known, suggesting that hunting could have been a factor in its extinction.[3]

Research history

The earliest specimen of Megatherium americanum was discovered in 1787 by Manuel de Torres, a Dominican friar and naturalist, from a ravine on the banks of the Lujan River in what is now northern Argentina, which at the time was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in the Spanish Empire. Torres described the bones as a ‘wonder and providence of the Lord’. On the orders of the then viceroy of la Plata, Nicolás Cristóbal del Campo, Marqués de Loreto, the specimen was moved to the capital Buenos Aires. There the skeleton was drawn for the first time by José Custodio Sáa y Faria in a horse-like posture. Campo summoned a number of local indigenous leaders to ask if they had heard of the animal. The skeleton was then transferred by Campo to the Royal Cabinet of Natural History of Madrid (now the National Museum of Natural Sciences MNCN) in 7 crates, which had arrived and been unpacked by late 1788.[4]

At the direction of the cabinets main taxidermist Juan Bautista Bru, the specimen was then mounted for public exhibition (which remains unaltered in the modern museum display). In 1796 a scientific description of the skeleton was published authored by Bru along with engineer Joseph Garriga, with engravings by Manuel Navarro. As the work was going through the process of publication in 1795, preliminary prints of the paper were obtained by French diplomat Philippe-Rose Roume who was in Madrid at the time, who sent them to the National Museum of Natural History (Muséum national d'histoire naturelle) in Paris, France, where they were seen by French anatomist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier.[4]

Cuvier, working solely from the prints from Madrid and not visiting the specimen personally,[4] and using comparative anatomy with "edentate" mammals (now recognised as members of the order Xenarthra) in the collection of the Paris museum,[5] correctly recognised that the remains represented those of a giant sloth, and an animal that was entirely extinct and not living. In early 1796, somewhat before the full publication of the work by Bru, Garriga and Navarro, Cuvier published a paper naming the species Megatherium americanum (literally "Great American beast"),[4] becoming the first fossil mammal to be identified with both a genus and species name. Which description had priority has been controversial in the past. Cuvier later wrote a fuller description in 1804, which was republished in his famous 1812 book Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes. Cuvier identified Megatherium as a sloth primarily on the basis of its skull morphology, the dental formula and the shoulder, while regarding the anatomy of its limbs as more similar to armadillos and anteaters. Cuvier suggested that based on the proportions of its limbs (which are approximately equal to each other), that Megatherium did not jump or run, nor crawl like living sloths, with the presence of a clavicle and well developed crests on the humerus, suggesting to Cuvier that the animal probably used its forelimbs to grasp.[5] A later publication in 1823 by Cuvier suggested that giant carapaces found in the Pampas also belonged to Megatherium, but British paleontologist Richard Owen in 1839 demonstrated that these actually belonged to another extinct group of xenarthrans called glyptodonts that were related to armadillos.[6]

Additional remains of Megatherium were collected by Charles Darwin during the Voyage of the Beagle in the 1830s, these remains were assigned by Richard Owen in 1840 to the species Megatherium cuvieri, which had been named by Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest in 1822. These remains are now assigned to M. americanum.[6]

Owen later wrote a monograph series from 1851 to 1860 thoroughly describing the anatomy of M. americanum.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

From the late 19th century onward additional species of Megatherium were described. In 1888 Argentine explorer Francisco Moreno erected the species Megatherium filholi for remains found in the Late Pleistocene of Argentina.[13][14][15] In 1880 Paul Gervais and Florentino Ameghino described the species M. tarijense from remains of Pleistocene age found in Bolivia. In 1893 Rodolfo Amando Philippi erected the species M. sundti and M. medinae from remains found in the Pleistocene of Bolivia and Chile, respectively.[16][17] In 1921, Florentino's brother Carlos Ameghino and Lucas Kraglievich described the species Megatherium gallardoi based on remains found in the Pampas of Northern Argentina, of Early-Middle Pleistocene age.[18][19] In 2001, the species M. altiplanicum was described based on remains found in the Pliocene of Bolivia.[20] In 2004, the species Megatherium urbinai was erected based on remains found in Pleistocene aged deposits in Peru.[21] In 2006, the species Megatherium celendinense was erected for remains of Pleistocene age found in the Peruvian Andes.[22]

Taxonomy and evolution

Megatherium is divided into 2 subgenera, Megatherium and Pseudomegatherium. Taxonomy according to Pujos (2006) and De Iuliis et al (2009):[22][23]

- Subgenus Megatherium

- †M. altiplanicum Saint-André & de Iuliis 2001

- †M. americanum Cuvier 1796

- †M. gallardoi Ameghino & Kraglievich, 1921

- Subgenus Pseudomegatherium Kraglievich 1931

- †M. celendinense Pujos 2006

- †M. medinae Philippi 1893

- †M. sundti Philippi 1893

- †M. tarijense Gervais & Ameghino, 1880

- †M. urbinai Pujos & Salas 2004

Megatherium gallardoi Ameghino & Kraglievich, 1921 from the Pampas dating to the Early to Middle Pleistocene[15] has sometimes been regarded as a synonym of M. americanum.[19] The species Megatherium filholi Moreno, 1888 also from the Pleistocene of the Pampas region, historically regarded to be a junior synonym of M. americanum representing juvenile individuals has been suggested to be valid by some recent authors.[14] Megatherium gaudryi Moreno (1888) from Argentina, of uncertain temporal provenance but possibly Pliocene in age, may also be valid.[15]

Mitochondrial DNA sequences obtained from M. americanum indicates that three-toed sloths (Bradypus) are their closest living relatives. Phylogeny of sloths after Delsuc et al. 2019.[24]

| Folivora (sloths) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Megatheriidae is suggested to have diverged from other sloth families during the Oligocene, around 30 million years ago.[24] The subfamily to which Megatherium belongs, Megatheriinae, first appeared in the Middle Miocene in Patagonia, at least 12 million years ago, represented by the genus Megathericulus.[25] The earliest known remains of the genus Megatherium are known from the Pliocene, found in Bolivia (M. altiplanicum) and the Pampas (indeterminate species), dating to at least 3.6 million years ago.[15][20] M. altiplanicum is suggested to be more closely related to M. americanum than to species of Pseudomegatherium. Phylogeny of Megatheriinae after Pujos, 2006:[22]

| Megatheriinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Megatherium americanum first appears in the fossil record during the second half of the Middle Pleistocene, from around 400,000 years ago.[26]

Description

Size

M. americanum is one of the largest known ground sloths, with a total body length of around 6 metres (20 ft).[27] Volumetric analysis suggests that a full grown M. americanum weighed around 3,700–4,000 kilograms (8,200–8,800 lb), comparable to an Asian elephant.[28][29][30] The Late Pleistocene Andean-Altiplano Pseudomegatherium species Megatherium celendinense was likely comparable in size. These species were only rivalled in size amongst ground sloths by the closely related Eremotherium and the distantly related Lestodon. The Chilean Pseudomegatherium species M. sundti was much smaller, with an estimated body mass of only 1,253 kilograms (2,762 lb), with the Peruvian Megatherium urbinai, Bolivian Megatherium tarijense and the Chilean Megatherium medinae (all also belonging to Pseudomegatherium) also having a considerably smaller body size than M. americanum.[31] The Pliocene Megatherium (Megatherium) species M. altiplanicum has been estimated to weigh 977–1,465 kilograms (2,154–3,230 lb).[20]

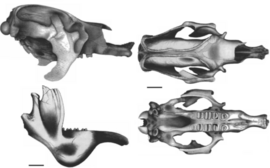

Skull and jaws

The head of Megatherium is relatively small compared to body size.[29] The skull of M. americanum has a relatively narrow snout/muzzle with a ossified nasal septum, and is suggested to have had a thick prehensile upper lip, similar to that of the living black rhinoceros.[32] The morphology of the hyoid bones in Megatherium suggests that they were relatively rigid, this along with the short distance between the hyoid and the mandibular symphysis (the joint connecting the two halves of the lower jaw) suggests that the tongue had limited ability to protrude, and thus Megatherium lacked the long prehensile tongue often attributed to it historically.[33] The skull is roughly cylindrical in shape, with the cranial region of the skull being narrow. The jugal bone of M. americanum has strongly developed ascending and descending processes.[34] The skull of M. americanum has a relatively small cranial cavity (and thus brain) relative to skull size, with the skull having extensive sinus spaces.[35] In many species of Megatherium, the lower jaw is relatively deep, which served to accommodate the very long hypselodont (evergrowing) teeth,[20] which are considerably proportionally longer than those of other ground sloths. Like other ground sloths, the number of teeth in the jaw is reduced to 5 and 4 teeth in each half of the upper and lower jaws, respectively, and the teeth lack enamel. The teeth of Megatherium americanum have sharp crests separated by v-shaped valleys, which interlock with the teeth on the opposing jaw.[34] These teeth were self-sharpening, akin to rodent incisors.[36] The skull and jaws of M. americanum show adaptation to powerful vertical biting.[34] M. americanum and M. altiplanicum are distinguished from species of the subgenus Pseudomegatherium by the fusion of the maxilla and premaxilla, while members of Pseudomegatherium are distinguished from those species by their flat occipital condyles.[22]

Axial skeleton

Like other xenarthrans, the posterior trunk vertebrae of Megatherium americanum have additional xenarthrous processes that articulate with the other vertebrae. The ischium was connected to the caudal vertebrae, forming a synsacrum. The sacrum was composed of 5 vertebrae. The pubic symphysis is reduced. The tail is large in size.[29]

Limbs

The bones of the forelimbs of M. americanum are relatively elongate and thin. The three fingers in the middle of the hand bore claws, while the cuneiform hand bones did not touch the ulna.[29] The olecranon process of the ulna was relatively short.[37] Like other xenarthrans, but unlike most other mammals, Megatherium possesses clavicles (collarbones), which serves to support the forelimb. Like other sloths, the clavicle is merged with the acromion of the scapula.[38] The femur was massive and roughly rectangular in shape.[29] As in most megatheriines, the tibia and fibula of Megatherium species are fused together at their proximal (closest to hip) end, while in M. americanum and M. tarijense, they are also fused together at their distal (closest to foot) ends.[39] The foot was heavily modified from those of other mammals and earlier ground sloths, with a reduction in the number of digits on the inner part of the foot (digits I and II being lost), the increase in the size and robustness (thickness) of the metapodial elements of the outer digits, with the loss or reduction of the phalangeal bones. The calcaneum is wide and elongate posteriorly. The foot is suggested to have been inwardly rotated, historically the foot was suggested to be near vertical, though a recent study suggests that the angle was much shallower. The weight was primarily borne on the outer digits and the calcaneum.[40] M. urbinai differs from M. americanum based on various characters of the feet and hands.[21]

Ecology

Remains of Megatherium americanum have been found in low elevation areas to the east of the Andes mountains in northern Patagonia, the Pampas and adjacent areas in what is now northern Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, southern Bolivia and Rio Grande do Sul in southern Brazil.[31] Megatherium americanum inhabited temperate, arid-to semi arid open habitats.[41] During the Last Glacial Period, the Pampas was generally drier than it is at present with many areas exhibiting a steppe-like environment dominated by grass, with some areas of woodland.[31]

Although some authors have suggested that Megatherium was an omnivore,[37] isotopic analysis has supported an entirely herbivorous diet for Megatherium.[42] Megatherium americanum is suggested to have been a browser that was a selective feeder on the foliage, twigs and fruits of trees and shrubs.[32][43] The sharp cusps of the teeth served to shear plant material.[36] Megatherium is widely thought to have been able to adopt a bipedal posture to use its forelimbs to grasp vegetation, though whether it was capable of moving in this posture is uncertain.[44] Analysis of injuries on the clavicles of M. americanum individuals suggests that the species probably habitually moved in a quadrupedal posture and assumed a bipedal posture next to trees to feed on high-growing leaves, likely using its forelimbs to brace itself against the tree trunk, as well as to pull down higher branches within reach of its prehensile lip.[38] Isotopic analysis suggests that some individuals of M. americanum at certain times and places also consumed grass.[45] The smaller Megatherium tarijense has been suggested to have had a mixed feeding-browsing diet.[46] Preserved coprolites attributed to Megatherium suggests that its diet included plants like Fabiana, Ephedra (Ephedra breana), beebrush, Junellia, and Chuquiraga.[47]

Whether or not Megatherium had a slow metabolism like living tree sloths is uncertain. Analysis of the nutrient foramina in the diaphysis (shaft) of the femur of Megatherium americanum shows that they are more similar to those of other large living mammals like elephants than living tree sloths, which may suggest that it had a metabolism more similar to non-xenarthran mammals and was capable of vigorous activity similar to living elephants.[48] However, isotopic analysis of teeth suggests that Megatherium had a somewhat lower body temperature than non-xenarthran mammals, around 30–32 °C (86–90 °F), comparable to that of living tree sloths, implying a lower metabolic rate.[49] Megatherium americanum has been traditionally reconstructed as being covered with a thick coat of fur.[49] Due to its very large body size, some authors have alternatively argued that Megatherium americanum was probably hairless like modern elephants for thermodynamic reasons.[50] However this has been disputed, with other authors suggesting based on thermodynamic modelling assuming a living xenarthran-like metabolism that Megatherium species probably had a dense coat of fur around 3 centimetres (1.2 in) thick to be able to tolerate the relatively cool environments they inhabited.[49]

Based on fossil trackways and the anatomy of its inner ear, which is considerably different from living sloths and more similar to those of armadillos, species of Megatherium, while probably not capable of moving at considerable speed due to limitations of their skeletal anatomy (with one study estimating a max speed of approximately 2.2 metres per second (7.2 ft/s) or 7.92 kilometres per hour (4.92 mph), a fraction of the 5–6 metres per second (16–20 ft/s) or 18–21.6 kilometres per hour (11.2–13.4 mph) top speed observed for living elephants[49]) were likely significantly more agile and mobile than living sloths, which are only capable of moving 0.5–0.6 kilometres per hour (0.31–0.37 mph). Species of Megatherium likely relied on their large adult body size to protect themselves against predators.[51] Like many other large mammals, Megatherium is suggested to have had a slow life cycle in accordance with a K-selection strategy. Megatherium americanum is suggested to have given birth to a single large offspring at a time.[52]

The anatomy of its forelimb bones suggests that M. americanum had the ability to rapidly and powerfully extend its arms, which likely made its claws effective stabbing weapons.[37] It may have used its claws like this to defend itself, as living tree sloths do.[38] Although some authors in the 19th century suggested that Megatherium engaged in digging behaviour, this has been disputed by other scholars, and the morphology of its limb bones do not appear to display significant adaptations to digging unlike some ground sloths such as mylodontids.[53]

In the Pampas, Megatherium americanum lived alongside other megafauna species, including the large ground sloth Lestodon, along with the smaller (but still large) ground sloths Mylodon, Glossotherium, and Scelidotherium, the glyptodonts (very large armadillos with fused round carapaces covering the body) Glyptodon, Doedicurus, and Panochthus, the large camel-like ungulate Macrauchenia and rhinoceros-like Toxodon, the gomphothere (elephant-relative) Notiomastodon, the equines Hippidion and Equus neogeus, the large short-faced bear Arctotherium, and the large sabertooth cat Smilodon.[54] The range of Megatherium americanum overlaps little with its similarly sized tropical relative Eremotherium, with their co-occurrence only confidently reported from a few localities in Southern Brazil, and it is unclear whether they were contemporary at these localities.[55]

Relationship with humans and extinction

During the Late Pleistocene, six species of Megatherium were present in South America, including M. americanum in the Pampas and adjacent regions, and the 5 species of Pseudomegatherium in the vicinity of the Andes.[31]

The youngest unambiguous dates for Megatherium are from the end of the Late Pleistocene. Supposed early Holocene dates obtained for Megatherium americanum and other Pampas megafauna have been questioned, with suggestions that they are likely due to humic acid contamination of the collagen used to radiocarbon date the bones.[3] Megatherium disappeared simultaneously along with the vast majoriy (>80%) of other large (megafaunal) South American mammals, as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event.[56] The use of bioclimatic envelope modeling indicates that the area of suitable habitat for Megatherium had shrunk and become fragmented by the mid-Holocene. While this alone would not likely have caused its extinction, it has been cited as a possible contributing factor.[57]

Towards the end of the Late Pleistocene, humans first arrived in the Americas, with some of the earliest evidence of humans in South America being the Monte Verde II site in Chile, dating to around 14,500 years Before Present (~12,500 BC).[58] The extinction interval of Megatherium and other megafauna coincides with the appearance and abundance of Fishtail points, which are suggested to have been used to hunt megafauna, across the Pampas region and South America more broadly.[59] At the Paso Otero 5 site in the Pampas of northeast Argentina, Fishtail points are associated with burned bones of Megatherium americanum and other extinct megafauna. The bones appear to have been deliberately burned as a source of fuel. Due to the poor preservation of the bones there is no clear evidence of human modification.[60]

There is evidence for the butchery of Megatherium by humans. Two M. americanum bones, an ulna[61] and an atlas vertebra,[62] from separate collections, bear cut marks suggestive of butchery, with the latter suggested to represent an attempt to exploit the contents of the head.[62] A kill site dating to around 12,600 years Before Present (BP), is known from Campo Laborde in the Pampas in Argentina, where a single individual of M. americanum was slaughtered and butchered at the edge of a swamp, which is the only confirmed giant ground-sloth kill site in the Americas. At the site several stone tools were present, including the fragment of a projectile point.[3] Another possible kill site is Arroyo Seco 2 near Tres Arroyos in the Pampas in Argentina, where M. americanum bones amongst those of other megafauna were found associated with human artifacts dating to approximately 14,782–11,142 cal yr BP.[63] This hunting may have been a factor in its extinction.[59]

Cultural references

The Megatherium Club, named for the extinct animal and founded by William Stimpson, was a group of Washington, D.C.–based scientists who were attracted to that city by the Smithsonian Institution's rapidly growing collection, from 1857 to 1866.

References

- ^ a b Saint-André, P. A.; De Iuliis, G. (2001). "The smallest and most ancient representative of the genus Megatherium Cuvier, 1796 (Xenarthra, Tardigrada, Megatheriidae), from the Pliocene of the Bolivian Altiplano" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 23 (4): 625–645. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Zurita, A. E.; Carlini, A. A.; Scillato-Yané, G. J.; Tonni, E. P. (2004). "Mamíferos extintos del Cuaternario de la Provincia del Chaco (Argentina) y su relación con aquéllos del este de la región pampeana y de Chile". Revista Geológica de Chile. 31 (1): 65–87. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082004000100004.

- ^ a b c Politis, Gustavo G.; Messineo, Pablo G.; Stafford, Thomas W.; Lindsey, Emily L. (March 2019). "Campo Laborde: A Late Pleistocene giant ground sloth kill and butchering site in the Pampas". Science Advances. 5 (3): eaau4546. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.4546P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau4546. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6402857. PMID 30854426.

- ^ a b c d Pimentel, Juan (2021), Pimentel, Juan; Thurner, Mark (eds.), "Megatherium", New World Objects of Knowledge, A Cabinet of Curiosities, University of London Press, pp. 231–236, ISBN 978-1-908857-82-8, JSTOR j.ctv1vbd275.38, retrieved 2024-04-23

- ^ a b Argot, Christine (2008), Sargis, Eric J.; Dagosto, Marian (eds.), "Changing Views in Paleontology: The Story of a Giant (Megatherium, Xenarthra)", Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology, Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 37–50, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6997-0_3, ISBN 978-1-4020-6996-3, retrieved 2024-04-23

- ^ a b Fernicola, J. C., Vizcaino, S. F., & De Iuliis, G. (2009). The fossil mammals collected by Charles Darwin in South America during his travels on board the HMS Beagle. Revista De La Asociación Geológica Argentina, 64(1), 147–159. Retrieved from https://revista.geologica.org.ar/raga/article/view/1339

- ^ Owen R (1851) On the Megatherium (Megatherium americanum, Blumenbach). Part I. Preliminary observations on the exogenous processes of vertebrae. Phil Trans R Soc Lond 141:719–764

- ^ Owen R (1855) On the Megatherium (Megatherium americanum, Cuvier and Blumenbach). Part II. Vertebrae of the trunk. Phil Trans R Soc Lond 145:359–388

- ^ Owen R (1856) On the Megatherium (Megatherium americanum, Cuvier and Blumenbach). Part III. The skull. Phil Trans R Soc Lond 146:571–589

- ^ Owen R (1858) On the Megatherium (Megatherium americanum, Cuvier and Blumenbach). Part IV. Bones of the anterior extremities. Phil Trans R Soc Lond 148:261–278

- ^ Owen R (1859) On the Megatherium (Megatherium americanum, Cuvier and Blumenbach). Part V. Bones of the posterior extremities. Phil Trans R Soc Lon149:809–829

- ^ Owen R (1861) Memoir on the Megatherium, or Giant Ground-sloth of America (Megatherium americanum, Cuvier). Williams and Norgate, London

- ^ Moreno, F.P. (1888): Informe preliminar de los progresos del Museo La Plata durante el primer semestre de 1888. – Boletín del Museo La Plata, 1: 1-35.

- ^ a b Agnolin, Federico L.; Chimento, Nicolás R.; Brandoni, Diego; Boh, Daniel; Campo, Denise H.; Magnussen, Mariano; De Cianni, Francisco (2018-09-01). "New Pleistocene remains of Megatherium filholi Moreno, 1888 (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Pampean Region: Implications for the diversity of Megatheriinae of the Quaternary of South America". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen. 289 (3): 339–348. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2018/0777. hdl:11336/80117. ISSN 0077-7749. S2CID 134660849.

- ^ a b c d Chimento, Nicolás R.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Brandoni, Diego; Boh, Daniel; Magnussen, Mariano; De Cianni, Francisco; Isla, Federico (April 2021). "A new record of Megatherium (Folivora, Megatheriidae) in the late Pliocene of the Pampean region (Argentina)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 107: 102950. Bibcode:2021JSAES.10702950C. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102950.

- ^ Philippi, R.A. 1893a. Vorläufige Nachricht über fossile Säugethierknochen von Ulloma, Bolivia. Zeitschrift der deutschen geologischen Gesellschaft 45: 87–96.

- ^ Philippi, R.A. 1893b. Noticias preliminares sobre huesos fósiles de Ulloma. Anales de la Universidad de Chile 82: 499–506.

- ^ C. Ameghino, L. Kraglievich Descripción del "Megatherium gallardoi" C. Amegh. descubierto en el Pampeano inferior de la ciudad de Buenos Aires Anales del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Buenos Aires, 31 (1921), pp. 134–156

- ^ a b Brandoni D., Soibelzon E. & Scarano A. 2008. — On Megatherium gallardoi (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Megatheriidae) and the Megatheriinae from the Ensenadan (lower to middle Pleistocene) of the Pampean region, Argentina. Geodiversitas 2008 (4): 793-804.

- ^ a b c d Saint-André P.-A. & de Iuliis G. 2001. — The smallest and most ancient representative of the genus Megatherium Cuvier, 1796 (Xenarthra, Tardigrada, Megatheriidae), from the Pliocene of the Bolivian Altiplano. Geodiversitas 2001 (4): 625–645.

- ^ a b Pujos, François; Salas, Rodolfo (May 2004). "A new species of Megatherium (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Sacaco and Tres Ventanas, Peru". Palaeontology. 47 (3): 579–604. Bibcode:2004Palgy..47..579P. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00376.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ^ a b c d Pujos, François (2006). "Megatherium celendinense sp. nov. from the Pleistocene of the Peruvian Andes and the phylogenetic relationships of Megatheriines". Palaeontology. 49 (2): 285–306. Bibcode:2006Palgy..49..285P. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00522.x. S2CID 84225654.

- ^ De Iuliis, Gerardo; Pujos, François; Tito, Giuseppe (2009-12-12). "Systematic and taxonomic revision of the Pleistocene ground sloth Megatherium (Pseudomegatherium) tarijense (Xenarthra: Megatheriidae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1244–1251. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1244D. doi:10.1671/039.029.0426. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 84272333.

- ^ a b Delsuc, Frédéric; Kuch, Melanie; Gibb, Gillian C.; Karpinski, Emil; Hackenberger, Dirk; Szpak, Paul; Martínez, Jorge G.; Mead, Jim I.; McDonald, H. Gregory; MacPhee, Ross D.E.; Billet, Guillaume; Hautier, Lionel; Poinar, Hendrik N. (June 2019). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E2031D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. PMID 31178321.

- ^ Brandoni, Diego; Carlini, Alfredo A; Anaya, Federico; Gans, Phil; Croft, Darin A (September 2018). "New Remains of Megathericulus patagonicus Ameghino, 1904 (Xenarthra, Tardigrada) from the Serravallian (Middle Miocene) of Bolivia; Chronological and Biogeographical Implications". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25 (3): 327–337. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9384-y. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ Prado, José Luis; Alberdi, María Teresa; Bellinzoni, Jonathan (June 2021). "Pleistocene Mammals from Pampean Region (Argentina). Biostratigraphic, Biogeographic, and Environmental Implications". Quaternary. 4 (2): 15. doi:10.3390/quat4020015. ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ Naish, Darren (November 2005). "Fossils explained 51: Sloths". Geology Today. 21 (6): 232–238. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.2005.00538.x. ISSN 0266-6979.

- ^ Brassey, Charlotte A.; Gardiner, James D. (August 2015). "An advanced shape-fitting algorithm applied to quadrupedal mammals: improving volumetric mass estimates". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (8): 150302. Bibcode:2015RSOS....250302B. doi:10.1098/rsos.150302. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 4555864. PMID 26361559.

- ^ a b c d e Casinos, Adrià (March 1996). "Bipedalism and quadrupedalism in Megatheriurn: an attempt at biomechanical reconstruction". Lethaia. 29 (1): 87–96. Bibcode:1996Letha..29...87C. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01842.x. ISSN 0024-1164.

- ^ Fariña RA, Czerwonogora A, di Giacomo M (March 2014). "Splendid oddness: revisiting the curious trophic relationships of South American Pleistocene mammals and their abundance". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 86 (1): 311–31. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420120010. PMID 24676170.

- ^ a b c d McDonald, H. Gregory (June 2023). "A Tale of Two Continents (and a Few Islands): Ecology and Distribution of Late Pleistocene Sloths". Land. 12 (6): 1192. doi:10.3390/land12061192. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ^ a b Bargo, M. Susana; Toledo, Néstor; Vizcaíno, Sergio F. (February 2006). "Muzzle of South American Pleistocene ground sloths (Xenarthra, Tardigrada)". Journal of Morphology. 267 (2): 248–263. doi:10.1002/jmor.10399. ISSN 0362-2525. PMID 16315216.

- ^ Perez, L. M.; Toledo, N.; De Lullis, G.; Bargo, M. S.; Vizcaino, S. F. (2010). "Morphology and Function of the Hyoid Apparatus of Xenarthran Fossils (Mammalia)". Journal of Morphology. 271 (9): 1119–1133. doi:10.1002/jmor.10859. PMID 20730924. S2CID 8106788.

- ^ a b c Bargo, M.S. 2001. The ground sloth Megatherium americanum: Skull shape, bite forces, and diet. – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 46,2, 173–192.

- ^ Boscaini, Alberto; Iurino, Dawid A.; Sardella, Raffaele; Gaudin, Timothy J.; Pujos, François (2023), Dozo, María Teresa; Paulina-Carabajal, Ariana; Macrini, Thomas E.; Walsh, Stig (eds.), "The Endocranial Cavities of Sloths (Xenarthra, Folivora): Insights from the Brain Endocast, Bony Labyrinth, and Cranial Sinuses", Paleoneurology of Amniotes, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 737–760, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13983-3_19, ISBN 978-3-031-13982-6, retrieved 2024-05-14

- ^ a b Green, Jeremy L.; Kalthoff, Daniela C. (2015-08-03). "Xenarthran dental microstructure and dental microwear analyses, with new data for Megatherium americanum (Megatheriidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 96 (4): 645–657. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv045. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ a b c Fariña, R. A.; Blanco, R. E. (1996-12-22). "Megatherium, the stabber". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 263 (1377): 1725–1729. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0252. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 9025315.

- ^ a b c Chichkoyan, Karina V.; Villa, Chiara; Winkler, Viola; Manuelli, Luigi; Acuña Suarez, Gabriel E. (2022-12-16). "Paleopathologies of the Clavicles of the Giant Ground Sloth Megatherium americanum (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Pleistocene of the Pampean Region (Argentina)". Ameghiniana. 59 (6). doi:10.5710/AMGH.15.10.2022.3509. ISSN 0002-7014.

- ^ Bonini, Ricardo A.; Brandoni, Diego (December 2015). "Pyramiodontherium Rovereto (Xenarthra, Tardigrada, Megatheriinae) from the Early Pliocene of San Fernando, Catamarca Province, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 52 (6): 647–655. doi:10.5710/AMGH.16.06.2015.2902. hdl:11336/42299. ISSN 0002-7014.

- ^ Toledo, Néstor; De Iuliis, Gerardo; Vizcaíno, Sergio F.; Bargo, M. Susana (December 2018). "The Concept of a Pedolateral Pes Revisited: The Giant Sloths Megatherium and Eremotherium (Xenarthra, Folivora, Megatheriinae) as a Case Study". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25 (4): 525–537. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9410-0. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ Varela, Luciano; Tambusso, P. Sebastián; Patiño, Santiago J.; Di Giacomo, Mariana; Fariña, Richard A. (December 2018). "Potential Distribution of Fossil Xenarthrans in South America during the Late Pleistocene: co-Occurrence and Provincialism". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25 (4): 539–550. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9406-9. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ Bocherens, Hervé; Cotte, Martin; Bonini, Ricardo A.; Straccia, Pablo; Scian, Daniel; Soibelzon, Leopoldo; Prevosti, Francisco J. (August 2017). "Isotopic insight on paleodiet of extinct Pleistocene megafaunal Xenarthrans from Argentina". Gondwana Research. 48: 7–14. Bibcode:2017GondR..48....7B. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2017.04.003. hdl:11336/56592.

- ^ Bargo, M. S., & Vizcaíno, S. F. (2008). Paleobiology of Pleistocene Ground Sloths (Xenarthra, Tardigrada): Biomechanics, Morphogeometry and Ecomorphology Applied to the Masticatory Apparatus. Ameghiniana, 45(1), 175–196.

- ^ Milne, Nick; Toledo, Nestor; Vizcaíno, Sergio F. (September 2012). "Allometric and Group Differences in the Xenarthran Femur". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 19 (3): 199–208. doi:10.1007/s10914-011-9171-0. hdl:11336/193251. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ Sanz-Pérez, Dánae; Hernández Fernández, Manuel; Tomassini, Rodrigo L.; Montalvo, Claudia I.; Beilinson, Elisa; Gasparini, Germán M.; Domingo, Laura (June 2022). "The Pampean region (Argentina) underwent larger variation in aridity than in temperature during the late Pleistocene: New evidence from the isotopic analysis of mammalian taxa". Quaternary Science Reviews. 286: 107555. Bibcode:2022QSRv..28607555S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107555.

- ^ Dantas, Mário A. T.; Campbell, Sean Cody; McDonald, H. Gregory (December 2023). "Paleoecological inferences about the Late Quaternary giant sloths". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 30 (4): 891–905. doi:10.1007/s10914-023-09681-5. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ H. Gregory McDonald and Gerardo de Iuliis: Fossil history of sloths. In: Sergio F. Vizcaíno and WJ Loughry (eds.): The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida, 2008, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Varela, Luciano; Tambusso, Sebastián; Fariña, Richard (2024-08-07). "Femora nutrient foramina and aerobic capacity in giant extinct xenarthrans". PeerJ. 12: e17815. doi:10.7717/peerj.17815. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 11316464. PMID 39131616.

- ^ a b c d Deak, Michael D.; Porter, Warren P.; Mathewson, Paul D.; Lovelace, David M.; Flores, Randon J.; Tripati, Aradhna K.; Eagle, Robert A.; Schwartz, Darin M.; Butcher, Michael T. (March 2025). "Metabolic skinflint or spendthrift? Insights into ground sloth integument and thermophysiology revealed by biophysical modeling and clumped isotope paleothermometry". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 32 (1). doi:10.1007/s10914-024-09743-2. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ Fariña, R. A. (2002). Megatherium, the hairless: appearance of the great Quaternary sloths (Mammalia; Xenarthra). Ameghiniana, 39(2), 241–244.

- ^ Billet, G.; Germain, D.; Ruf, I.; de Muizon, C.; Hautier, L. (December 2013). "The inner ear of Megatherium and the evolution of the vestibular system in sloths". Journal of Anatomy. 223 (6): 557–567. doi:10.1111/joa.12114. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 3842198. PMID 24111879.

- ^ Andrea, Elissamburu (July 2016). "Prediction of offspring in extant and extinct mammals to add light on paleoecology and evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 453: 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.033.

- ^ Amson, Eli; Nyakatura, John A. (December 2018). "The Postcranial Musculoskeletal System of Xenarthrans: Insights from over Two Centuries of Research and Future Directions". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25 (4): 459–484. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9408-7. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ S.F. Vizcaíno, R.A. Fariña, J.C. Fernicola Young Darwin and the ecology and extinction of Pleistocene South American fossil mammals Rev. Asoc. Geol. Argent., 64 (1) (2009), pp. 160-169

- ^ Lopes, Renato Pereira; Dillenburg, Sergio Rebello; Pereira, Jamil Corrêa; Sial, Alcides Nóbrega (2021-09-26). "The paleoecology of Pleistocene giant megatheriid sloths: stable isotopes (δ13C, δ18O) of co-occurring Megatherium and Eremotherium from southern Brazil". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 24 (3): 245–264. doi:10.4072/rbp.2021.3.06.

- ^ Barnosky, Anthony D.; Koch, Paul L.; Feranec, Robert S.; Wing, Scott L.; Shabel, Alan B. (2004). "Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents". Science. 306 (5693): 70–75. Bibcode:2004Sci...306...70B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.574.332. doi:10.1126/science.1101476. PMID 15459379. S2CID 36156087.

- ^ Lima-Ribeiro, Matheus Souza; et al. (December 2012). "Potential Suitable Areas of Giant Ground Sloths Dropped Before its Extinction in South America: the Evidences from Bioclimatic Envelope Modeling". Natureza & Conservação. 10 (2): 145–151. doi:10.4322/natcon.2012.022.

- ^ Dillehay, Tom D.; Pino, Mario; Ocampo, Carlos (2021-01-02). "Comments on Archaeological Remains at the Monte Verde Site Complex, Chile". PaleoAmerica. 7 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1080/20555563.2020.1762399. ISSN 2055-5563. S2CID 224935851.

- ^ a b Prates, Luciano; Perez, S. Ivan (2021-04-12). "Late Pleistocene South American megafaunal extinctions associated with rise of Fishtail points and human population". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 2175. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.2175P. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22506-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8041891. PMID 33846353.

- ^ G. Martínez, M. A. Gutiérrez, Paso Otero 5: A summary of the interdisciplinary lines of evidence for reconstructing early human occupation and paleoenvironment in the Pampean region, Argentina, in Peuplements et Préhistoire de l’Amérique, D. Vialou, Ed. (Muséum National d’ Histoire Naturelle. Departement de Prehistoire, U.M.R, Paris, 2011), pp. 271–284.

- ^ Chichkoyan, Karina V.; Martínez-Navarro, Bienvenido; Moigne, Anne-Marie; Belinchón, Margarita; Lanata, José L. (June 2017). "The exploitation of megafauna during the earliest peopling of the Americas: An examination of nineteenth-century fossil collections". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (4): 440–451. Bibcode:2017CRPal..16..440C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2016.11.003.

- ^ a b Martínez-Navarro, B.; Chichkoyan, K.V.; Moigne, A.-M.; Cioppi, E.; Belinchón, M.; Lanata, J.L. (2017). Description and interpretation of a Megatherium americanum atlas with evidence of human intervention. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. OCLC 1084743779.

- ^ Bampi, Hugo; Barberi, Maira; Lima-Ribeiro, Matheus S. (December 2022). "Megafauna kill sites in South America: A critical review". Quaternary Science Reviews. 298: 107851. Bibcode:2022QSRv..29807851B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107851. S2CID 253876769.

External links

- Prehistoric sloths

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Pliocene xenarthrans

- Pleistocene xenarthrans

- Piacenzian first appearances

- Holocene extinctions

- Pliocene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Fossils of Argentina

- Fossils of Bolivia

- Fossils of Brazil

- Fossils of Chile

- Fossils of Colombia

- Fossils of Paraguay

- Fossils of Peru

- Fossils of Uruguay

- Fossil taxa described in 1796

- Taxa named by Georges Cuvier

- Neogene Argentina