Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari

| Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari | |

|---|---|

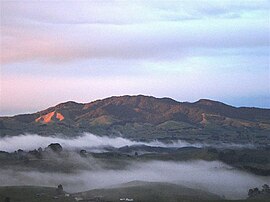

The wildlife sanctuary covers the Maungatautari peak | |

| |

| Location | Waikato Region, New Zealand |

| Coordinates | 38°02′S 175°34′E / 38.033°S 175.567°E |

| Area | 3,400 ha |

| Website | www |

Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari, is a protected natural area in Waikato Region, New Zealand where the biodiversity of 3,400 ha of forest is being restored. The sanctuary covers the mountain peak, Maungatautari.

Most of New Zealand's ecosystems have been severely modified by the introduction of land mammals that were not present during the evolution of its ecosystems, and have had a devastating impact on both native flora and fauna.[1] The sanctuary, surrounded by a pest-exclusion fence, is a good example of an ecological island, which allows the original natural ecosystems to recover by minimising the impact of introduced flora and fauna.

Ecological area

[edit]

Maungatautari, as an eroded volcano was chosen as a suitable site for a major ecological project for a number of reasons, including the diversity of its terrain, the relative integrity of natural areas in spite of some human engineered changes, the commitment of surrounding communities, and the feasibility of fence-construction given surrounding developed terrain.[citation needed]

Some elements of the diversity of Maungatautari took scientists by surprise. In April 2006, the discovery of 100 silver beech trees caused considerable excitement in the botanical community. The tree, native to southern New Zealand, had not previously been believed to be present on Maungatautari, although researchers who came to investigate emphasized that the tree had probably been established during the last ice age. The largest of the trees were estimated to be several centuries old. Jim Mylchreest, Maungatautari Trust's chief executive, pointed out that the trees were not only exciting in themselves, but also for the fungi and insects they might host that also may not have been expected to be present on Maungatautari.[citation needed]

Species found

[edit]In December 2004, eleven endangered Hochstetter's frogs were found living on Maungatautari in a rocky region. There had already been discussions about potentially reintroducing the Hochstetter's frog to the preserve, and the rare discovery of the small population in an environment being prepared to protect them excites the scientific community.[citation needed]

A dead Duvaucel's gecko was found in a mouse trap in March 2010; this was the first sighting of this species on mainland New Zealand for almost 100 years, probably indicating a surviving population of the gecko within Maungatautari.[2]

Ecological restoration plan

[edit]Because poisons and trapping, traditional methods of pest control, have limited success and seldom last long, the creators of the plan decided to enclose the 34 square kilometres of bush with a 47 km pest-exclusion fence to create an ecological island. When the environment was rendered suitable, the area was to be repopulated with the entire suite of charismatic species that may now be locally extinct, such as North Island brown kiwi, North Island kōkako, kākāriki, tuatara and many others. Kākā already visited regularly and were likely to become resident if suitable methods are employed.[citation needed]

In November 2003, the Trust constructed two exclosures, at the north and south of Maungatautari, totalling 1.1 square kilometres. The Trust used these areas to demonstrate the fence's feasibility and to test pest removal methods, which were launched in September 2004. The exclosures are now predator-free and were used as holding areas for native species while the main fence was being built.[citation needed]

In November 2005 a 3 hectare area adjacent to the Southern Enclosure, the Tautari Wetland, was gifted to the Trust by the Tauroa family for takahē and other wetland birds. A Tuatarium for the future was designed and planted inside the area.[citation needed]

In July 2004, the Trust began constructing the Xcluder fence. In September 2006 the Trust completed fencing the entire 34 square kilometres to exclude all pests (and was able to take advantage of parts of the exclosures' fencing constructed at Stage 1). Then the Trust began eliminating pests by dropping poison, starting with brodifacoum in November 2006. A second application was made in December 2006. The combined effect of the poison, trapping and hunting eliminated brown rats, black rats, stoats, cats, weasels, ferrets, red deer, fallow deer, pigs, goats, possums, hedgehogs, rabbits and hares. In 2007 the sole remaining pest species was mice, and poison was dropped a third time, in September that year, to eradicate them. This failed, and in 2011 the trust introduced a new policy, focusing on controlling rather than eradicating mice.[3]

One of the greater challenges facing the designers of the Xcluder fence adopted for the purpose was addressing entry at streams. Since water levels fluctuate and a fence needed to address both debris and fish migration, the Xcluder was outfitted with an electronic surveillance system to alert the Trust if a watergate fails to properly close. There have been other challenges with the fence, including storm damage in July 2007 that was quickly repaired.[citation needed]

In July 2006, a viewing tower was constructed near a northern rata grove in the southern exclosure.[citation needed]

Species reintroduction

[edit]Since the beginning of the project, native species have returned to the area either naturally or through reintroduction. In July 2007, a 300% increase was discovered in the native beetle population of the southern enclosure.[4]

In December 2005 Maungatautari witnessed its first kiwi call in approximately a hundred years. Radio signals in April 2007 suggested that a kiwi may be sitting on an egg, but that nest was found to be bare. In September 2007, two kiwi eggs were discovered. Although one proved infertile, the other hatched in December 2007, the first kiwi egg known to have hatched on Maungatautari in a century.

As of 2021, 320 founders of the North Island brown kiwi (Apteryx mantelli) western taxon have been introduced.

In June 2006, the Trust began reintroducing species, starting with a pair of critically endangered takahē. In April 2007, three species of endangered whitebait (kōkopu or native trout) were reintroduced. In May, kākā were put into a special enclosure to allow them to acclimatise before they were released; they quickly attracted wild companions. In November of that year, seven kākā were released from the aviary.

On 3 December 2007, the trust announced that they planned to reintroduce North Island robins, North Island kōkako, tuatara, popokatea (whiteheads) and hihi (stitchbirds) in 2008. March 2009 saw the release of 60 whiteheads (popokatea).

Between 2009 and 2011, 155 hihi (stitchbirds) were released over 3 translocations (135 from Tiritiri Matangi Island and 20 from Little Barrier Island).

2011 saw the release of 40 North Island robins from Pureora Forest with a further 40 in 2012.

In 2012 and 2013 200 Mahoenui giant weta (Deinacrida mahoenui) were introduced into the sanctuary. Also in 2012, 50 tuatara from Stephens Island were reintroduced.

In 2013, 40 North Island saddleback were translocated from Tiritiri Matangi Island.

In 2015, 40 North Island kōkako were translocated from Pureora Forest.

In 2021, 80 riflemen (titipounamu) were translocated from Pirongia and Pureora.

On July 20, 2023, four kākāpō were reintroduced to the sanctuary, becoming the first kākāpō living in mainland New Zealand in almost 40 years.[5] Despite extensive improvements to the perimeter fence, in October 2023, one of the kākāpō escaped by using a downed tree to climb out. The bird was located using the signal from its GPS transmitter and returned to the sanctuary.[6] A second group of six birds was introduced to the sanctuary in September. However, two further kākāpō found a way over the fence, and in November the Department of Conservation temporarily removed three birds from the sanctuary to a southern predator-free island, leaving the kākāpō population in the sanctuary at seven. A further four birds were subsequently removed leaving the of number of kākāpō on the maunga at three. The department commented that "“Kākāpō are flightless but are excellent climbers who can use their wings to parachute from treetops".[7]

Native species

[edit]Mammals

[edit]- New Zealand long-tailed bat (Chalinolobus tuberculatus)[8]

Birds

[edit]

- Grey teal (Anas gracilis)

- Australasian shoveler (Anas rhynchotis)

- Grey duck (Anas superciliosa)

- New Zealand bellbird (korimako) (Anthornis melanura)

- North Island brown kiwi (kiwi) (Apteryx mantelli)

- Australasian bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus)

- Shining cuckoo (Chrysococcyx lucidas)

- Australasian harrier (Circus approximans)

- White-faced heron (Egretta novaehollandiae)

- New Zealand falcon (kārearea) (Falco novaeseelandiae)

- Grey warbler (riroriro) (Gerygone igata)

- New Zealand kingfisher (Halcyon sancta)

- Wood pigeon (kererū) (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae)

- Welcome swallow (Hirundo neoxena)

- Morepork (Ninox novaeseelandiae)

- Stitchbird (hihi) (Notiomystis cincta)

- North Island tomtit (Miromiro) (Petroica macrocephala toitoi)

- Whitehead (pōpokotea) (Mohoua albicilla)

- Black shag (Phalacrocorax carbo)

- Little pied cormorant (Phalacrocorax melanoleucos)

- New Zealand dabchick (Poliocephalus rufopectus)

- Takahē (Porphyrio hochstetteri)

- Pūkeko (Porphyrio porphyrio)

- North Island fantail (Piwakawaka) (Rhipidura fulginosa placabilis)

- Kākāpō (Strigops habroptila)

- Paradise shelduck (Tadorna variegata)

- Silvereye (Zosterops lateralis)

- Tūī (Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae)

- Kākā (Nestor meridionalis)

- North Island saddleback (tiēke) (Philesturnus rufusater)

- Kōkako (Callaeas wilsoni)

Amphibians

[edit]- Hochstetter's frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri)[9]

Reptiles

[edit]- Copper skink (Cyclodina aenea)

- Forest gecko (Hoplodactylus granulatus)

- Pacific gecko (Hoplodactylus pacifica)

- Auckland green gecko (Naultinus elegans elegans)

- Duvaucel's gecko (Hoplodactylus duvaucelli)

Fish

[edit]- New Zealand longfin eel (Anguilla dieffenbachii)

- Giant kōkopu, (Galaxias argenteus)[10]

- Banded kōkopu, (Galaxias fasciatus)[10]

- Shortjaw kōkopu, (Galaxias postvectis)[10]

Invertebrates

[edit]- Onychophora

- Mecodema oconnori

- Lasiorhynchus barbicornis (New Zealand giraffe weevil)

(Survey yet to be done)

References

[edit]- ^ "Theme 1: Our ecosystems and biodiversity". Ministry for the Environment. 9 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 July 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ Neems, Jeff (22 April 2010). "Rare lizard killed in trap". Waikato Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Maungatautari Ecological Island Trust | Biodiversity Management". www.maungatrust.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2011.

- ^ "Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari - Our Story". Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Kākāpō return to mainland in historic translocation". www.doc.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 3 April 2024. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ Franke-Bowell, Jonah (17 October 2023). "The great kākāpō escape at Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari". Waikato Times. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Zollickhofer, Danielle (28 November 2023). "Kākāpō sent to live on an island after 'parachute' escape attempts". Waikato Herald. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari Wildlife". Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari Wildlife". Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari Wildlife". Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

External links

[edit]