Haqqani network

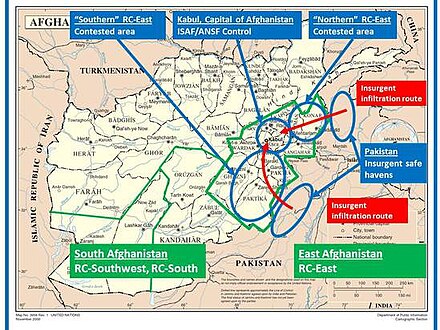

The Haqqani network is an Afghan Islamist group, built around the family of the same name,[18] that has used asymmetric warfare in Afghanistan to fight against Soviet forces in the 1980s, and US-led NATO forces and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan government in the 21st century. It is recognized as a terrorist organization by the United Nations.[19] It is considered to be a "semi-autonomous"[20] offshoot of the Taliban.[21][22][23] It has been most active in eastern Afghanistan and across the border in north-west Pakistan.[24]

The Haqqani network was founded in 1970[25] by Jalaluddin Haqqani, a fundamentalist of the Zadran tribe, who fought for Yunus Khalis's mujahideen faction against the Soviets in the 1980s. Jalaluddin Haqqani died in 2018 and his son Sirajuddin Haqqani now leads the group.[26] The Haqqani network was one of the Reagan administration's most CIA-funded anti-Soviet groups in the 1980s.[27][3] In the latter stages of the war, Haqqani formed close ties with foreign jihadists, including Osama bin Laden,[20] becoming one of his closest mentors.[24] The Haqqani network pledged allegiance to the Taliban in 1995,[28] and has been an increasingly incorporated wing of the group ever since.[29] Taliban and Haqqani leaders have denied the existence of the "network", saying it is no different from the Taliban.[28] In 2012, the United States designated the Haqqani network as a terrorist organization.[30] In 2015, Pakistan banned the Haqqani network as part of its National Action Plan.[31]

The elusive[18] Haqqani network has been blamed for some of the deadliest attacks during the War in Afghanistan (2001-2021), having a reputation of frequently using suicide bombings and being able to carry out complex attacks. They had long been suspected by the United States of ties with the Pakistani military establishment, a claim denied by Pakistan.[20][24] They have also been suspected of criminal activities such as smuggling and trafficking across the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.[32] Alongside Al-Qaeda, the Haqqani network maintains close ties with the anti-India Jaish-e-Mohammed, and the Lashkar-e-Taiba.[32] Following the Fall of Kabul (2021), the group was put in charge of domestic security by the Taliban.[32] The Wall Street Journal called the group the Taliban's "most radical and violent branch."[33]

Etymology

[edit]The word Haqqani comes from Darul Uloom Haqqania, a madrassa in Pakistan that Jalaluddin Haqqani attended.[34]

Ideology and goals

[edit]The Haqqani network's root values are nationalistic and religious. They are ideologically aligned with the Taliban, who have worked to eradicate Western influence and transform Afghanistan into a strictly sharia-following state and based on pashtunwali. This was exemplified in the government that formed after Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan. Both groups have the common goal of disrupting the Western military and political efforts in Afghanistan and driving them from the country permanently.[35] Through the 2000s–2010s, the group was demanding that US and Coalition Forces, made up mostly of NATO nations, withdraw from Afghanistan and no longer interfere with the politics or educational systems of Islamic nations.[35]

History

[edit]While the network became widely active during the Soviet–Afghan War in the 1980s, historical records show that Jalaluddin Haqqani had formed a movement in his local area Zerok District and assaulted the local pro-government Governor in an attack in June 1975.[25]

Jalaluddin Haqqani joined the Hezb-i Islami Khalis in 1978, becoming an Afghan mujahid. His personal Haqqani group was nurtured by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) during the 1980s Soviet–Afghan War.[36][37]

Haqqani family

[edit]The Haqqani family hails from southeastern Afghanistan and belongs to the Mezi clan of the Zadran Pashtun tribe.[36][38][39] Jalalludin Haqqani rose to prominence as a senior military leader during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.[39] Like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Haqqani was more successful than other resistance leaders at forging relationships with outsiders prepared to sponsor resistance to the Soviets, including the CIA, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), and wealthy Arab private donors from the Persian Gulf.

Al-Qaeda affiliation

[edit]Jalaluddin Haqqani commanded a mujahideen army from 1980 to 1992 and is credited with the recruitment of foreign fighters. Abdullah Azzam and Osama bin Laden both began their careers as volunteer fighters for the Haqqanis in the conflict against the Soviets. Al-Qaeda, the Taliban and the Haqqani network have been intertwined throughout their history.[40] According to a declassified US government report, a training facility belonging to Haqqani was located at Miram Shah, in which fighters of Pakistani Punjab, Arab, Kashmir, Uzbek and Afghanistan, all connected with either al-Qaeda or the Taliban, were in residence. Similar al-Qaeda-associated training facilities connected to Haqqani by US authorities have been reported in Northern Waziristan.[41]

The Haqqani network's relationship with al-Qaeda dates back to the founding of al-Qaeda. While al-Qaeda's stated goals are international in scope, the Haqqani network has limited its operations to regional matters concerning Afghanistan and Pashtun tribalism. The organizations share an ideological foundation; Jalaluddin Haqqani realized the importance of Azzam's "foundational Islamic legal decisions declaring the Afghan jihad a universally and individually binding duty borne by all Muslims worldwide." Though many Muslim leaders asked for aid from the oil wealthy Arab states in 1978 after Afghan communist and Soviet forces conquered Kabul, Jalaluddin Haqqani was the only Afghan Islamic resistance leader to also request foreign Muslim fighters, and his was the only group to welcome fighters from outside the region into its ranks, thus "linking it to the broader Jihad struggles and giving birth to the following decade to what would come to be known as global jihadism."[40]

The Haqqani network's use of the Saudi Arabian financiers and other Arab investors clearly highlights the groups understanding of global jihad.[40][vague]

Many sources believe Jalaluddin Haqqani and his forces assisted with the escape of al-Qaeda into safe havens in Pakistan. It is well documented that the Haqqani network assisted with the establishment of safe havens. Analyst Peter Bergen argues this point in his book The Battle for Tora Bora.[42][43][44] Judging by the possibilities and the amount of US military assets focused on such a small region, the theory that the Haqqani network aided in the escape seems reasonable. Regardless of exactly what occurred in those mountains, the Haqqanis played a role. And their actions of providing safe havens for al-Qaeda and Bin Laden show the strength of bond and some role in or knowledge of al-Qaeda and Bin Laden's escape.

On 26 July 2020, a United Nations report stated that the al-Qaeda group is still active in twelve provinces in Afghanistan and its leader al-Zawahiri is still based in the country,[45] and the UN Monitoring Team has estimated that the total number of al-Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan were "between 400 and 600 and that the leadership maintains close contact with the Haqqani Network" and in February 2020, "al-Zawahiri met with Yahya Haqqani, the primary Haqqani network contact with Al Qaeda since mid-2009, to discuss ongoing cooperation".[45]

Taliban affiliation

[edit]Foreign jihadists recognized the network as a distinct entity as early as 1994, but Haqqani was not affiliated with the Taliban until they captured Kabul and assumed de facto control of Afghanistan in 1996.[3][46] After the Taliban came to power, Haqqani accepted a cabinet-level appointment as Minister of Tribal Affairs.[9] Following the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the subsequent overthrow of the Taliban government, the Haqqanis fled to the bordering Pakistani tribal regions and regrouped to fight against coalition forces across the border.[47] The Haqqanis have been known to dissent from the Taliban line by permitting music and education for women.[48] As Jalaluddin has grown older his son Sirajuddin has taken over the responsibility of military operations.[49] Journalist Syed Saleem Shahzad reported that President Hamid Karzai invited c. 2002 the elder Haqqani to serve as Prime Minister in an attempt to bring "moderate" Taliban into the government. However, the offer was refused by Jalaluddin.[9]

Voice of America reported that the Taliban gave the Haqqani network control over security operations in Kabul on 19 August in the days following the fall of Kabul in the 2021 Taliban offensive.[50][51] That same day Anas Haqqani met with former Afghan president Hamid Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah and Hezb-e-Islami fighter Gulbuddin Hekmatyar seeking a formal transfer of power to the Taliban leader Abdul Ghani Baradar. Rumors circulated that Anas was receiving instructions directly from Sirajuddin Haqqani, who was himself in Quetta, Pakistan.[52]

United States

[edit]According to US military commanders, it is "the most resilient enemy network" and one of the biggest threats to the U.S.-led NATO forces and the Afghan government during the war in Afghanistan.[49][53] It is also the most lethal network in Afghanistan.[54] From 2010 the United States is offering a reward for information leading to the capture of their leader, Sirajuddin Haqqani, in the amount of $5,000,000.[55]

Obama administration

[edit]In September 2012, the Obama administration labeled the network as a foreign terrorist organization.[56] After this announcement, the Taliban issued a statement arguing that there is "no separate entity or network in Afghanistan by the name of Haqqani" and that Jalaluddin Haqqani is a member of Pakistan-based the Quetta Shura, the Taliban's top leadership council.[57]

Leadership

[edit]- Jalaluddin Haqqani – following his time as a commander in the Mujahideen Army (1980–1992), the network was founded under Haqqani during the insurgency against Soviet forces in Afghanistan during the 1980s. Haqqani himself was trained in Pakistan during the 1970s, in order to fight Prime Minister Mohammad Daud Khan, who had overthrown the previous ruler (and cousin), King Zahir Shah. During the Soviet invasion, the Pakistani government's Inter-Services Intelligence Agency became close with Haqqani and his organization, allowing them to become a main benefactor of American weapons, intelligence, and training. In the 1990s, Haqqani agreed to join the Taliban, arising to the position of Interior Minister. The United States attempted to convince Haqqani to sever ties with the Taliban, which he refused to do. In 2005 when Merjuddin Pathan was governor of the Khost Province, Haqqani approached him and wanting a dialogue with the Hamid Karzai Government, but neither Americans nor Karzai heeded the pleas of the governor. Afterwards when insurgency accentuated that Hamid Karzai's leadership in Afghanistan, approached Haqqani and offered him the position as Minister of Tribal Affairs in his cabinet, which Haqqani has also refused as it was too late. Since the emergence of the Haqqani network, Haqqani and his family have thrived off of the contacts made by Haqqani during the Cold War.[58] The BBC reported in July 2015 that Jalaluddin Haqqani had died of an illness and been buried in Afghanistan at least a year prior.[59] The Taliban rejected these reports.[60] On 3 September 2018, the Taliban released a statement via Twitter proclaiming Haqqani's death of an unspecified terminal illness.[61][62]

- Sirajuddin Haqqani – He is one of Jalaluddin's sons and currently leads the day-to-day activities of the network.

- Badruddin Haqqani – He was Sirajuddin's brother and an operational commander of the network. He was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan on 24 August 2012. Some Taliban commanders claimed the reports of his death were true while others claimed the reports were inaccurate.[63][64][65][66] However, U.S. and Pakistani officials confirmed his death.[67][68] The Taliban officially confirmed Badruddin's death a year later.[69]

- Abdulaziz Haqqani – He is one of Jalaluddin's sons who became very influential following Badruddin Haqqani's death. Currently he serves as deputy to his brother Sirajuddin Haqqani.[70][71][72]

- Khalil Haqqani was a leader of the Haqqani network.[73][74][75] The United States offered a US$5 million bounty for Khalil as one their most wanted terrorists.[76] In August 2021, after the fall of Kabul, Haqqani was seen roaming the streets of Kabul.[76] He was killed on 11 December 2024 by an ISIL suicide bomber in Kabul.[77][78]

- Sangeen Zadran (killed 6 September 2013)[79] – According to the US State Department, he was a senior lieutenant to Sirajuddin and the shadow governor for Paktika province in Afghanistan. He was also one of the captors of U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl.[63][80][81][82][83]

- Nasiruddin Haqqani – He was Sirajuddin's brother and a key financier and emissary of the network. As the son of Jalaluddin's Arab wife, he spoke fluent Arabic and traveled to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates for fundraising.[63][84] He was killed by unknown assailants in Islamabad, Pakistan, on 11 November 2013.[85]

- Maulvi Ahmad Jan (killed 21 November 2013)[86] The network's spiritual leader who was also responsible for organizing some of the network's most deadly attacks in Afghanistan.[86] He was subjected to UN sanctions[87] in March 2010[88] and had also served the Taliban government of Mullah Omar as federal minister for water and power,[88] before being appointed the Governor of the Zabul Province in 2000.[88] At the time of his death, Jan was thought be Sirajuddin Haqqani's chief deputy.[88]

- Abdul Aziz Abbasin – According to the U.S. Treasury, he is "a key commander in the Haqqani Network" and serves as the "Taliban shadow governor of Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan."[89]

- Haji Mali Khan – According to NATO, he is "the senior Haqqani commander in Afghanistan" and is uncle to Sirajuddin and Badaruddin.[90][91][92] ISAF also reported that he acted as an emissary between Baitullah Mehsud and the Haqqanis.[93] He was captured by ISAF forces on 27 September 2011.[91] He was released in a prisoner swap in November 2019.[94]

Following WikiLeaks' July 2010 publication of 75,000 classified documents the public learned that Sirajuddin Haqqani was in the tier one of the International Security Assistance Force's Joint Prioritized Effects List – its "kill or capture" list.[95]

Activities

[edit]Anand Gopal of The Christian Science Monitor, citing unnamed US and Afghan sources, reported in June 2009 that the leadership is based in Miranshah, North Waziristan in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan along the Afghan border.[5] It operates from at least three compounds: a Miranshah bazaar camp containing a madrassa and computer facilities, a compound in the nearby suburb of Sarai Darpa Khel and another compound in Danday Darpa Khel, where some of Jalaluddin's family stay.[38] The network is active in Afghanistan's southeastern areas of Paktia Province, Paktika Province, Khost Province, Wardak Province, Logar Province, and Ghazni Province.[5] In September 2011, Sirajuddin Haqqani told Reuters that the group feels "more secure in Afghanistan besides the Afghan people."[96]

Publications

[edit]The Haqqanis have been described as notable writers, having published a number of books as well as editing and contributing to magazines, three of them, Manba' al-Jihad (one version in Pashto and another in Arabic) and Nusrat al-Jihad ("Support for Jihad", in Urdu), totaling more than 1000 pages between 1989 and 1993.[97]

Funding

[edit]Some of Sirajuddin's brothers travel to the Persian Gulf region to raise funds from wealthy donors.[38][63] The New York Times reported in September 2011 that the Haqqanis have set up a "ministate" in Miranshah with courts, tax offices and madrassas, and that the network runs a series of front companies selling automobiles and real estate. They also receive funds from extortion, kidnappings and smuggling operations throughout eastern Afghanistan.[38] In an interview a former Haqqani commander called the extortion "the most important source of funding for the Haqqanis."[98] According to a tribal elder in Paktia, "Haqqani's people ask for money from contractors working on road construction. They are asking money or goods from shopkeepers... District elders and contractors are paying money to Afghan workers, but sometimes half of the money will go to Haqqani's people."[99]

Military strength

[edit]Haqqani is reported to run his own training camps, to recruit his own foreign fighters, and to seek out financial and logistic support on his own, from his old contacts.[49] Estimates of the Haqqanis's numbers vary. A 2009 New York Times article indicates that they are thought to have about 4,000 to 12,000 Taliban under their command while a 2011 report from the Combating Terrorism Center places its strength roughly at 10,000-15,000.[3][7] During a September 2011 interview, Sirajuddin Haqqani said the figure of 10,000 fighters, as quoted in some media reports, "is actually less than the actual number."[96] Throughout its history the network's operations have been conducted by small, semi-autonomous units organized according to tribal and sub-tribal affiliations often at the direction of and with the logistical support of Haqqani commanders.[3]

The network is comprised broadly of four groups: those who have been with Jalalludin since the Soviet-era jihad, those from Loya Paktiya who have joined since 2001, those from North Waziristan who have joined in more recent years, and foreign militants of primarily Arab, Chechen and Uzbek origins. Leadership roles are mostly filled with personnel from the first group while the relative neophytes from Loya Paktia and non-Pushtuns are not part of this inner circle.[38][39]

The Haqqani network pioneered the use of suicide attacks in Afghanistan and tend to use mostly foreign bombers whereas the Taliban tend to rely on locals in attacks.[5] The network, according to the National Journal, supplies much of the potassium chlorate used in bombs employed by the Taliban in Afghanistan. Also, the network's bombs use more sophisticated remote triggering devices than the pressure-plated activators used elsewhere in Afghanistan. Sirajuddin Haqqani told MSNBC in April 2009 that his fighters had, "acquired the modern technology that we were lacking, and we have mastered new and innovative methods of making bombs and explosives."[100]

In late 2011, a 144-page book attributed to Sirajuddin Haqqani began circulating in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Described by Newsweek as a "manual for guerrillas and terrorists," the Pashto-language book details instructions on setting up a jihadi cell, receiving financing, recruiting and training. The manual advises recruits that parental permission is not necessary for jihad, that all debts should be paid before joining, and that suicide bombings and beheadings are allowed by Islam.[101]

Attacks and alleged attacks

[edit]- 14 January 2008: The 2008 Kabul Serena Hotel attack is thought to have been carried out by the network.[49]

- March 2008: Kidnapping of British journalist Sean Langan was blamed on the network.[102]

- 27 April 2008: Assassination attempts on Hamid Karzai.[5]

- 7 July 2008: US intelligence blamed the network for 2008 Indian embassy bombing in Kabul.[103]

- 10 November 2008: The kidnapping of David Rohde was blamed on Sirajuddin Haqqani.[104]

- 30 December 2009: Camp Chapman attack is thought to have been carried out by the network.[105]

- 18 May 2010: May 2010 Kabul bombing was allegedly carried out by the network.[106]

- 19 February 2011: Kabul Bank in Jalalabad, Afghanistan.[107]

- 28 June 2011: According to ISAF, elements of the Haqqani network provided "material support" in the 2011 attack on the Hotel Inter-Continental in Kabul.[108] The Taliban claimed responsibility.[109]

- 10 September 2011: A massive truck bomb exploded outside Combat Outpost Sayed Abad in Wardak province, Afghanistan, killing five Afghans, including four civilians, and wounding 77 U.S. soldiers, 14 Afghan civilians, and three policemen. The Pentagon blamed the network for the attack.[110]

- 12 September 2011: US Ambassador Ryan Crocker blamed the Haqqani network for an attack on the US Embassy and nearby NATO bases in Kabul. The attack lasted 19 hours and resulted in the deaths of four police officers and four civilians. 17 civilians and six NATO soldiers were injured. Three coalition soldiers were killed. Eleven insurgent attackers were killed.[111]

- October 2011: Afghanistan's National Directorate of Security said that six people arrested in an alleged plot to assassinate President Karzai had ties to the Haqqani network.[112]

- 15 April 2012: Haqqani network fighters initiate the summer fighting season, conducting a complex attack across Kabul, Logar and Paktia provinces. Several western embassies in Kabul were attacked in the Say Wallah district.

- 1 June 2012: A massive suicide truck bomb breaches the southern perimeter wall of US Forward Operating Base Salerno in Khost province. A dozen Haqqani fighters wearing suicide vests entered the breach, but were isolated and killed by US Forces.

- 31 May 2017: a truck bomb exploded in a crowded intersection in Kabul, Afghanistan, near the German embassy,[113] killing over 150 and injuring 413,[114] mostly civilians, and damaging several buildings in the embassy.[115][116] The attack was the deadliest terror attack to take place in Kabul. Afghanistan's intelligence agency NDS claimed that the blast was planned by the Haqqani network.[117][118]

- 20 January 2018: an attack on Inter-Continental Hotel in Kabul killed 40 people, with the Afghan government accusing the Haqqani network.[119] The attack led to U.S. president Donald Trump pressuring Pakistan to expel Haqqani and Taliban leaders from their territory.[120]

- 27 January 2018: an ambulance was used as an explosive device in Kabul, exploding in a deadly attacked that claimed 103 lives. The U.S. and Afghan governments suspected the Taliban's Haqqani wing to have caused it.[121][122]

- 25 March 2020: a Sikh shrine was attacked by guns and bombs in Kabul, killing 25 civilians. The Afghan government blamed the Haqqani network and linked ISIS-K militants for the attack.[123] Members of both the Haqqani network and Islamic State were arrested in connection by the Afghan intelligence.[124]

Location

[edit]The Haqqani network operates in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in Northern Pakistan, near the southeastern border of Afghanistan.[125] The network has used the ambiguity of the FATA to cloak its activities and avoid interference. The strategy worked well until President Obama ramped up UAV strikes in the Northern Waziristan region. The organizational headquarters is supposedly in Miram Shah, where the group operates base camps to facilitate activities such as weapons acquisitions, logistical planning and military strategy formulation. Haqqani-controlled regions of northern Pakistan have also served as strategic safe havens for other Islamic militant organizations, such as al-Qaeda, the Pakistani Taliban (TTP), Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), and members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). The strategic location of the Haqqani network facilitates interaction between many of the insurgent groups.[38]

The Haqqani network's tribal connections in Northern Waziristan and the de facto regime that it has established with courts, law enforcement, medical care, and governance have often brought it great support from locals.[40] Its familiarity of terrain, such as mountain passes, also grants them excellent access between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In September 2011, Sirajuddin Haqqani claimed during a telephone interview with Reuters that the Haqqani network no longer maintained sanctuaries in northwestern Pakistan and the robust presence that it once had there and instead now felt safer in Afghanistan: "Gone are the days when we were hiding in the mountains along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Now we consider ourselves more secure in Afghanistan beside the Afghan people."[96] According to Haqqani, there were "senior military and police officials" who are aligned with the group and there are even sympathetic and "sincere people in the Afghan government who are loyal to the Taliban" who support the group's aim of liberating Afghanistan "from the clutches of occupying forces."[96] In response to questions from the BBC's Pashto service, Siraj denied any links to the ISI and stated that Mullah Omar is "our leader and we totally obey him."[126]

Foreign support

[edit]Pakistan's alleged involvement

[edit]While some Afghan and American officials accuse Pakistan of harboring the Haqqani network, Pakistan has denied any links.[28]

Abdul Rashid Waziri, a specialist at Kabul's Center for Regional Studies of Afghanistan, explains that links between the Haqqani network and Pakistan can be traced back to the mid-1970s,[36] before the 1978 Marxist revolution in Kabul. During the rule of President Daoud Khan in Afghanistan (1973–78), Jalaluddin Haqqani went into exile and based himself in and around Miranshah, Pakistan.[127] From there he began to form a rebellion against the government of Daoud Khan in 1975.[36] The network allegedly maintains ties with the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), and Pakistan's army had been reportedly reluctant to move against them in the past.[49][128]

The New York Times reported in September 2008 that Pakistan regards the Haqqani network as an important force for protecting its interests in Afghanistan in the event of American withdrawal from there and therefore is unwilling to move against them.[128] Pakistan presumably[by whom?] feels pressured that India, Russia, and Iran are gaining a foothold in Afghanistan. Since it lacks the financial clout of the other countries, Pakistan hopes that by being a sanctuary for the Haqqani network, it can assert some influence over its turbulent neighbor. In the words of a retired senior Pakistani official: "[We] have no money. All we have are the crazies. So the crazies it is."[129] The New York Times and Al Jazeera later reported in June 2010 that Pakistan's Army chief General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani and chief of the ISI General Ahmad Shuja Pasha were in talks with Afghan President Hamid Karzai to broker a power-sharing agreement between the Haqqani network and the Afghan government.[130][131] Reacting to this report both President Barack Obama and CIA director Leon Panetta responded with skepticism that such an effort could succeed.[132] The effort to mediate between the Haqqanis and the Afghan government was launched by Pakistan after intense pressure by the US to take military action against the group in North Waziristan.[133] Karzai later denied meeting anyone from the Haqqani network.[134] Subsequently, Kayani also denied that he took part in the talks.[135]

Anti-American groups of Gul Bahadur and Haqqani carry out their activities in Afghanistan and use North Waziristan as rear.[136] The group's links to Pakistan have been a sour point in Pakistan–United States relations. In September 2011, the Obama administration warned Pakistan that it must do more to cut ties with the Haqqani network and help eliminate its leaders, adding that "the United States will act unilaterally if Pakistan does not comply."[137] In testimony before a US Senate panel, Admiral Mike Mullen stated that the network "acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Agency."[138] Although some U.S. officials allege that the ISI supports and guides the Haqqanis,[138][139][140][141][142] President Barack Obama declined to endorse that position and stated that "the intelligence is not as clear as we might like in terms of what exactly that relationship is"[143] and US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said "We have no evidence of" Pakistani involvement in attacks on the US embassy in Kabul.[144]

Pakistan in return rejected the notion that it maintained ties with the Haqqani network or used it in a policy of waging a proxy war in neighboring Afghanistan. Pakistani officials deny the allegations by asserting that Pakistan had no relations with the network. In response to the allegations, Interior Minister Rehman Malik claimed that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had "trained and produced" the Haqqani network and other mujahideen during the Soviet–Afghan War.[145][146][147][148] The Pakistani interior minister also warned that any incursion on Pakistani territory by U.S. forces will not be tolerated. A Pakistani intelligence official insisted that the American allegations are part of "pressure tactics" used by the United States as a strategy "to shift the war theatre."[149] An unnamed Pakistani official was reported to have said after a meeting of the nation's top military officials that "We have already conveyed to the US that Pakistan cannot go beyond what it has already done".[150] However, Pakistani claims were contradicted by the network's warnings against any U.S. military incursions into North Waziristan.[145][147] However a month after the allegation, ties improved slightly and the US asked Pakistan to assist it in starting negotiation talks with the Taliban.[151]

There was a paradigm shift within the Pakistani military and in 2014 the Pakistani Armed Forces launched a major offensive Operation Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan, aimed at displacing all militants foreign and domestic from Pakistan, including the Haqqanni network. The operation was commanded by General Qamar Javed Bajwa.[152]

Alleged Iranian involvement

[edit]Antonio Giustozzi, an expert on the Taliban with the Royal United Services Institute in London, said that the Haqqani network has been "getting closer" to Iran as Pakistan and Saudi Arabia cut funding to it.[12] In August 2020, US intelligence agencies assessed that Iran has been offering bounties to the Haqqani network to target US and coalition troops in Afghanistan. The US intelligence agencies identified payments linked to at least six attacks carried out by the militant group in 2019 including the Bagram Airfield attack.[11][153]

However, Iranian authorities denied making any payments to the militant group to target US troops in Afghanistan. Iran's Foreign Ministry spokesman, Saeed Khatibzadeh, categorised the US intelligence report as propaganda. He also said that the US is trying to hide its "miscalculations" in Afghanistan by resorting to such propaganda.[154]

Opponents

[edit]ISAF Military offensives

[edit]In July 2008, Jalaluddin's son Omar Haqqani was killed in a firefight with coalition forces in Paktia.[155] In September 2008, Daande Darpkhel airstrike drones fired six missiles at the home of the Haqqanis and a madrasah run by the network. However both Jalaluddin and Sirajuddin were not present though several family members were killed.[103] Among 23 people killed was one of Jalaluddin's two wives, sister, sister-in-law and eight of his grandchildren.[128] In March 2009, the US State Department announced a reward of $5 million for information leading to the location, arrest, or conviction of Sirajuddin under the Rewards for Justice Program.[156] In May 2010, US senator and United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Chair Dianne Feinstein wrote to United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton urging her to add the Haqqani network to U.S. State Department list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations.[157]

ISAF and Afghan forces killed a network leader, Fazil Subhan, plus an unknown number of Haqqani militiamen, in a raid in Khost in the second week of June 2010. In a press release, ISAF reported that Subhan helped facilitate the movement of Al-Qaeda fighters into Afghanistan.[158][159]

In late July 2011, U.S. and Afghan special forces killed dozens of insurgents during an operation in eastern Paktika province to clear a training camp the Haqqani network used for foreign (Arab and Chechen) fighters; reports of the number killed varied, with one source saying "more than 50"[160] to "nearly 80".[161] Disenfranchised insurgents told security forces where the camp was located, the coalition said.[160]

On 1 October 2011, NATO announced the capture of Haji Mali Khan, "the senior Haqqani commander in Afghanistan," during an operation in Jani Khel district of Afghanistan's Paktia province. Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid denied that the capture occurred while Haqqani network members declined to respond to the announcement.[90][91]

According to an unnamed Pakistani official a US drone strike on a compound killed Jamil Haqqani, an "important Afghan commander of Haqqani network" responsible for logistics in North Waziristan, on 13 October 2011. Three other network fighters were also killed in the two missile blasts. The compound was located in Dandey Darpakhel village, about 7 km (4 miles) north of Miranshah.[162]

In mid-October 2011, Afghan and NATO forces launched "Operation Shamshir" and "Operation Knife Edge" against the Haqqani network in south-eastern Afghanistan, with the intent to counter possible security threats in the border regions. An ISAF spokesman said that Operation Shamshir "was aimed at securing key population centers and expanding the Kabul security zone,"[163] while Afghan Defense Minister, Abdul Rahim Wardak, explained that Operation Knife Edge would "help eliminate the insurgents before they struck in areas along the troubled frontier."[164] The two operations ended on 23 October 2011 and at least 20 insurgents, of the some 200 killed or captured, had ties to the Haqqani network according to ISAF.[4][163]

On 2 November 2011, The Express Tribune reported that the Pakistani Army had agreed with the United States to restrict the network's movement along the Afghan border in exchange for America dropping its demands for a full-scale offensive. The report emerged soon after a visit by Hillary Clinton to Pakistan.[165]

Curtis M. Scaparrotti, commander of International Security Assistance Force Joint Command, has said that Haqqani can be defeated through a combination of a layered defense in Afghanistan and interdiction against the sanctuaries in Pakistan.[166]

In June 2014 a drone attack reportedly killed 10 members of the Haqqani network including a high-level commander, Haji Gul, in the country's tribal area of North Waziristan. The Pakistan government publicly condemned the attack, but according to a government official had privately approved it.[167]

Pakistani military offensive

[edit]In 2014, the Pakistani Armed Forces launched a major offensive Operation Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan aimed at displacing all militants foreign and domestic, including the Haqqani network from its soil. On 5 November 2014, Lt. Gen. Joseph Anderson, a senior commander for US and Nato forces in Afghanistan, said in a Pentagon-hosted video briefing from Afghanistan that the Haqqani network is now "fractured" like the Taliban. "They are fractured. They are fractured like the Taliban is. That's based pretty much on the Pakistan's operations in North Waziristan this entire summer-fall," he said, acknowledging the effectiveness of Pakistan's military offensive. "That has very much disrupted their efforts in Afghanistan and has caused them to be less effective in terms of their ability to pull off an attack in Kabul," Anderson added. [168]

Sanctions

[edit]Until 1 November 2011, six Haqqani network commanders were designated as terrorists under Executive Order 13224 since 2008 and their assets were frozen while prohibiting others from engaging in financial transactions with them:[93]

- In March 2008, the US State Department designated Sirajuddin Haqqani a terrorist and a year later issued a $5 million bounty for information leading to his capture.[93]

- The State Department placed Nasiruddin Haqqani on its list of terrorists in July 2010.[93]

- In February 2011, Khalil al Rahman Haqqani was designated a terrorist by the US State Department.[93]

- In an effort to stop the flow of funds to the network, the US State Department announced on 16 August 2011 measures against Sangeen Zadran as "Shadow Governor for Paktika Province, Afghanistan and a commander of the Haqqani Network." The US designated Zadran under Executive Order 13224 while the United Nations listed him under Security Council Resolution 1988.[81][82]

- The U.S. Department of Treasury added Abdul Aziz Abbasin, "a key commander in the Haqqani Network", to the list of individuals on the executive order in September 2011.[89][93]

- On 1 November 2011, Haji Mali Khan, who was already in ISAF custody, was added to the list.[93]

In September 2011, the US Senate Appropriations Committee voted to make a $1 billion counter-insurgency aid package to the Pakistani military conditional upon Pakistani action against militant groups, including the Haqqani network. The decision would still need to receive approval from the US House of Representatives and the US Senate.[169] According to the press release, "[t]he bill includes strengthened restrictions on assistance for Pakistan by conditioning all funds to the Government of Pakistan on cooperation against the Haqqani network, al Qaeda, and other terrorist organizations, with a waiver, and funding based on achieving benchmarks."[170]

On 7 September 2012, the Obama administration blacklisted the group as a foreign terrorist organization. The decision was mandated by Congress and was a source of debate within the administration.[56][171][172]

On 5 November 2012, the United Nations Security Council added the network to a blacklist of Taliban-related groups.[173]

On 9 May 2013, the government of Canada listed it as a terror group.[174]

In March 2015, the UK proscribed the Haqqani network as a terror group.[175]

On 25 August 2015, Abdulaziz Haqqani was sanction as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist with a reward of up to $5 million USD for information regarding his location.[176][70][177]

Attempts to negotiate

[edit]US officials confirmed that they held preliminary talks during the summer of 2011 with representatives of the militant network at the request of the ISI. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that the US had reached out to the Haqqanis to gauge their willingness to engage in a peace process and that "Pakistani government officials helped to facilitate such a meeting."[178] The New York Times reported that talks secretly began in late August 2011 in the United Arab Emirates between a midlevel American diplomat and Ibrahim Haqqani, Jalalludin's brother. Gen. Ahmed Shuja Pasha, head of the ISI, brokered the discussion, but little resulted from the meeting.[179]

References

[edit]- ^ "Who are the Haqqanis?". Quilliam. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ a b "The Haqqani Network". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rassler, Don; Vahid Brown (14 July 2011). "The Haqqani Nexus and the Evolution of al-Qaida" (PDF). Harmony Program. Combating Terrorism Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ a b c NATO: 200 Afghan militants killed, captured Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Deb Riechmann. 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Gopal, Anand (1 June 2009). "The most deadly US foe in Afghanistan". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Sirajuddin Haqqani dares US to attack N Waziristan". The Express Tribune. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ a b Perlez, Jane (14 December 2009). "Rebuffing U.S., Pakistan Balks at Crackdown". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ "Taliban announces death of Jalaluddin Haqqani | FDD's Long War Journal". 4 September 2018. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Syed Salaam Shahzad (5 May 2004). "Through the eyes of the Taliban". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2004. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ Winchell, Sean P. (2003), "Pakistan's ISI: The Invisible Government", International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 16 (3): 374–388, doi:10.1080/713830449, S2CID 154924792

- ^ a b Cohen, Zachary (17 August 2020). "US intelligence indicates Iran paid bounties to Taliban for targeting American troops in Afghanistan". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b Bezhan, Frud (9 June 2020). "Iranian Links: New Taliban Splinter Group Emerges That Opposes U.S. Peace Deal". www.rferl.org. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

The Haqqani network has strong ties to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. But Giustozzi said the network is "getting closer" to Iran as Islamabad and Riyadh cut funding to it.

- ^ "Afghanistan Faces Tough Battle as Haqqanis Unify the Taliban - ABC News". ABC News. 8 May 2016. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (25 June 2021). "Taliban's deputy emir issues guidance for governance in newly seized territory". FDD's Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (7 June 2021). "U.N. report cites new intelligence on Haqqanis' close ties to al Qaeda". FDD's Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". United States Department of State. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Shah, Pir Zubair; Gall, Carlotta (31 October 2011). "For Pakistan, deep ties to militant network may trump U.S. Pressure". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Youssef, Sune Engel Rasmussen and Nancy A. (27 August 2021). "In Taliban-Ruled Afghanistan, Al Qaeda-Linked Haqqani Network Rises to Power". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021 – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ "1.3. Haqqani network". Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Haqqani network: Afghanistan's most feared militants". France 24. 21 August 2021. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Khan, Haq Nawaz; Constable, Pamela (19 July 2017). "A much-feared Taliban offshoot returns from the dead". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Alikozai, Hasib Danish (13 January 2018). "Afghan General: Haqqani Network, Not IS, Behind Spike in Violence". VoA News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "What Is the Haqqani Network?". VOA News. June 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ a b c "What is the Haqqani network, which is linked to the Taliban and al-Qaeda?". The Independent. 7 September 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Mapping Militants". Stanford University. 18 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matthew; Mehsud, Ihsanullah Tipu (31 July 2015). "Founder of Haqqani Network Is Long Dead Aide Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Abubakar Siddique (26 September 2011). "Questions Raised About Haqqani Network Ties with Pakistan". ETH Zurich Center for Security Studies. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Anwar, Madeeha; Zahid, Noor (1 June 2017). "What Is the Haqqani Network?". Extremism Watch. Voice of America. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Mashal, Mujib (4 September 2018). "Taliban Say Haqqani Founder Is Dead. His Group Is More Vital Than Ever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "Haqqani network to be designated a terrorist group". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ Zahra-Malik, Mehreen (16 January 2015). "Pakistan bans Haqqani network after security talks with Kerry". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ a b c Vohra, Anchal (27 August 2021). "It's Crazy to Trust the Haqqanis". Archived from the original on 9 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "In Taliban-Ruled Afghanistan, al Qaeda-Linked Haqqani Network Rises to Power". Wall Street Journal. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Green, Matthew (13 November 2011). "'Father of Taliban' urges US concessions". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

The school also has a place in the hearts of the commanders of the Haqqani network, a family-run insurgent dynasty that specialises in Kabul suicide bombings. Jalaluddin Haqqani, the group's patriarch, studied at the seminary, from which he derives his name.

- ^ a b "Jeffrey Dressler; The Haqqani Network, A Strategic Threat." Institute for the Study of War 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Questions Raised About Haqqani Network Ties with Pakistan". International Relations and Security Network. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Coll, Steve (2004). Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin) pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b c d e f Gopal, Anand; Mansur Khan Mahsud; Brian Fishman (3 June 2010). "Inside the Haqqani network". Foreign Policy. The Slate Group, LLC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Mir, Amir (15 October 2011). "Haqqanis sidestep US terror list". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d Brown, V.; Rassler, D.; Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Network, 1973–2012. Columbia University Press 2013.

- ^ "Defense Intelligence Agency > FOIA > FOIA Electronic Reading Room > FOIA Reading Room: Other Available Records". Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "The Battle for Tora Bora"

- ^ Bergen, Peter; "The Battle for Tora Bora." The New Republic, 30 December 2009.

- ^ Smucker, Philip; Al-Qaeda's Great Escape: The Military and Media on Terror's Trail. Dulles, Virginia, Bassey's 2004.

- ^ a b "Al Qaeda active in 12 Afghan provinces: UN". Daijiworld. Indo-Asian News Service. 26 July 2020. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Herold, Marc (February 2002). "The failing campaign: A relentless American campaign seeking to kill Maulvi Jalaluddin Haqqani rains bombs on civilians as the most powerful mujahideen remains elusive". The Hindu. Vol. 19, no. 3.[dead link]

- ^ DeYoung, Karen (13 October 2011). "U.S. steps up drone strikes in Pakistan against Haqqani network". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Coll, Steve (2019). Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America's Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Penguin Group. p. 156. ISBN 9780143132509.

- ^ a b c d e Gall, Carlotta (17 June 2008). "Old-Line Taliban Commander is Face of Rising Afghan Threa". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Anti-Taliban Forces Retake Three Northern Afghan Districts". Voice of America. 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Hardline Haqqani Network Put in Charge of Kabul Security". Voice of America. 19 August 2021. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Haqqani network cadres control Kabul, Mullah Yaqoob in Kandahar". Hindustan Times. 19 August 2021. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Partlow, Joshua (27 May 2011). "Haqqani insurgent group proves resilient foe in Afghan war". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Dressler, Jeffrey (5 September 2012). "The Haqqani Network: A Foreign Terrorist Organization" (PDF). ISW. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Wanted Sirajuddin Haqqani Up to $5 Million Reward". Rewards for Justice. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric (6 September 2012). "U.S. Backs Blacklisting Militant Organization". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (9 September 2012). "Taliban call Haqqani Network a 'conjured entity'". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Lawrence, Kendall. "The Haqqani Network". Threat Convergence Profile Series. The Fund For Peace. October 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Afghan militant leader Jalaluddin Haqqani 'has died'". BBC News. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Taliban deny reports of Haqqani network founder's death". AFP. 1 August 2015. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "'The Kennedys of the Taliban movement' lose their patriarch". NBC News. 4 September 2018. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ @Zabihullah_4 (3 September 2018). "Statement of Islamic Emirate regarding passing away of prominent Jihadi figure, scholar and warrior Mawlawi Jalaluddin Haqqani (RA) https://justpaste.it/4z8if" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c d Khan, Zia (22 September 2011). "Who on earth are the Haqqanis?". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Top Haqqani network militant 'killed in Pakistan'". BBC News. 25 August 2012. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Rahim Faiez; Rebecca Santana (26 August 2012). "Taliban deny report of Haqqani commander's death". The State. AP. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "Afghanistan says sources confirm militant commander Badruddin Haqqani has been killed". The Washington Post. AP. 26 August 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Karen DeYoung (29 August 2012). "U.S. confirms killing of Haqqani leader in Pakistan". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Pakistani Officials Confirm Death of Key Militant". Time. AP. 30 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Bill Roggio (8 September 2013). "Taliban confirm death of Badruddin Haqqani in drone strike last year". The Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b Roggio, Bill (25 August 2015). "US adds Haqqani Network commander to list of global terrorists". FDD's Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ Lurie, Devin (September 2020). "The Haqqani Network: The Shadow Group Supporting the Taliban's Operations" (PDF). American Security Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Al Qaeda, ISIS and the Taliban" (PDF). Ultrascan Research Services. 10 October 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Top terrorist on most wanted list is welcomed into Kabul". Fox News. 21 August 2021. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "KHALIL AHMED HAQQANI | United Nations Security Council". www.un.org. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric (21 August 2021). "Afghanistan: U.S. May Seek Airlines' Help in Evacuation Effort". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Cunningham, Doug (11 December 2024). "Taliban refugee minister Khalil Haqqani killed in Kabul suicide bombing". UPI. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ Fraser, Simon; Davies, Caroline. "Khalil Haqqani: Taliban minister killed in bombing in Kabul". bbc.com. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Taliban-linked militant killed in U.S. drone strike in Pakistan". Reuters. 6 September 2013. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Designation of Haqqani Network Commander Sangeen Zadran." Office of the Spokesperson. 16 August 2011. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/08/170582.htm Archived 17 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 17 July 2012.

- ^ a b "US tries to stem funds to Haqqani network commander". The Express Tribune. AFP. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Designation of Haqqani Network Commander Sangeen Zadran". U.S. Department of State. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Afghan Taliban offers to swap captive U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl for 5 Guantanamo detainees". CBS News. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (22 July 2010). "US adds Haqqani Network, Taliban leaders to list of designated terrorists". The Long War Journal. Public Multimedia Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Khan, Tahir (11 November 2013). "Senior Haqqani Network leader killed near Islamabad". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b S.B. Shah (21 November 2013). "US drone strike kills senior Haqqani leader in Pakistan". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ "Security Council 1988 Sanctions Committee Adds Individual Abdul Rauf Zakir". United Nations. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d Amir Mir (25 November 2013). "Who was Maulvi Ahmad Jan, the droned Haqqani leader?". The News International. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Treasury Continues Efforts Targeting Terrorist Organizations Operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan". U.S. Department of Treasury. 29 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Haqqani leader captured in Afghanistan". Financial Times. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "NATO: Haqqani Leader Captured in Afghanistan". NPR. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Nato 'kills senior Haqqani militant in Afghanistan'". BBC News. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "US adds senior Haqqani Network leader to terrorist list". The Long War Journal. November 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Zucchino, David; Goldman, Adam (19 November 2019). "Two Western Hostages Are Freed in Afghanistan in Deal with Taliban". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ Matthias Gebauer; John Goetz; Hans Hoyng; Susanne Koelbl; Marcel Rosenbach; Gregor Peter Schmitz (26 July 2010). "The Helpless Germans: War Logs Illustrate Lack of Progress in Bundeswehr Deployment". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

Sirajuddin Haqqani is also associated with the foreign jihadists. Haqqani, known as 'Siraj,' is the son of the legendary Afghan mujahedeen leader Jalaluddin Haqqani. Together with the Taliban and Hekmatyar, the Haqqani clan of warlords are among the three greatest opponents of Western forces in Afghanistan. In the digital war logs, his name appeared in 'Tier 1' on a list of targets to be killed or taken captive, which qualified him as one of the Western alliance's most wanted terrorists.

- ^ a b c d "No sanctuaries in Pakistan': Haqqani network shifts base to Afghanistan". The Express Tribune. 18 September 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Vahid Brown and Don Rassler, Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Nexus, 1973-2012, Oxford University Press (2013), p. 14

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Scott Shane; Alissa J. Rubin (24 September 2011). "Brutal Haqqani Crime Clan Bedevils U.S. in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Toosi, Nahal (29 December 2009). "Haqqani network challenges US-Pakistan relations". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Dreazen, Yochi J., "The New Enemy", National Journal, 16 July 2011.

- ^ Moreau, Ron; Sami Yousafzai (14 November 2011). "Dueling Manifestos". The Daily Beast. The Newsweek. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Kidnapped US reporter makes dramatic escape from Taliban Archived 23 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 21 June 2009

- ^ a b U.S. Missiles Said To Kill 20 in Pakistan Near Afghan Border Archived 6 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, 9 September 2008

- ^ Taliban Wanted $25 Million for Life of New York Times Reporter Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, ABC News, 22 June 2009

- ^ Pakistan urges united reaction after CIA blast Archived 28 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, 3 January 2010

- ^ Rogio, Bill (24 May 2010). "Haqqani Network executed Kabul suicide attack". Public Multimedia. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Yaqubi, Mali Khan (15 June 2011). "Haqqani network threatens attacks on judges". Pajhwok Afghan News. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Roggio, Bill, "ISAF airstrike kills senior Haqqani Network commander involved in Kabul hotel attack Archived 1 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine", Long War Journal, 30 June 2011.

- ^ Kharsany, Safeeyah; Mujib Mashal (29 June 2011). "Manager gives account of Kabul hotel attack". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Jelinek, Pauline (Associated Press), "Haqqani group behind Afghan bombing, U.S. says", Military Times, 12 September 2011.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J; Ray Rivera; Jack Healy (14 September 2011). "U.S. Blames Kabul Assault on Pakistan-Based Group". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Six arrested over 'Karzai death plot'". Al Jazeera. 5 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ "Kabul bomb: Dozens killed in Afghan capital's diplomatic zone". BBC News. 31 May 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Mashal, Mujib; Abed, Fahim (31 May 2017). "Huge Bombing in Kabul Is One of Afghan War's Worst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "RS Claims Police Stopped Truck From Entering Green Zone". Tolonews. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Ehsan Popalzai; Faith Karimi (31 May 2017). "Afghanistan explosion: 80 killed in blast near diplomatic area". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Kabul bomb: Afghans blame Haqqani and Pakistan". Sky News. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Gul, Ayaz (31 May 2017). "Deadly Truck Bomb Rocks Kabul". VOA. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Faizi, Fatima; Mashal, Mujib (2018). "Afghan Forces Retake Control of Kabul Hotel After Deadly Siege". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Trump's bombast further divides Afghanistan and Pakistan, as civilians await meaningful change". 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Phil Stewart; Michelle Nichols (29 January 2018). "U.S. sees Haqqani network behind ambulance bombing in Kabul". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Amiri, Craig Nelson and Ehsanullah (28 January 2018). "Kabul Bombing: Death Toll Passes 100 in Suicide Attack With Ambulance". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Several Sikhs Feared Dead In Terror Attack At Kabul Gurudwara; IS Claims Strike". news.abplive.com ( ABP News Bureau). 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Sediqi, Abdul Qadir (6 May 2020). "Members of Islamic State-Haqqani network arrested over Kabul attacks". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Lawrence, Kendall (June 2010). "Threat Convergence Profile Series: The Haqqani Network" (PDF). The Fund For Peace. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Haqqani network denies killing Afghan envoy Rabbani". BBC. 3 October 2010. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Haqqani Network". The Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Perlez, Jane (9 September 2008). "U.S. attack on Taliban kills 23 in Pakistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Snake country". The Economist. Islamabad. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ Perlez, Jane; Gall, Carlotta (24 June 2010). "Pakistan Is Said to Pursue Foothold in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Karzai 'holds talks' with Haqqani". Al Jazeera English. 28 June 2010. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Shane, Scott (27 June 2010). "Pakistan's Plan on Afghan Peace Leaves U.S. Wary". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Syed, Baqir Sajjad (16 June 2010). "Pakistan trying to broker Afghan deal". Dawn. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Kabul dismisses report Karzai met militant leader". Agence France-Presse. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Kayani says he did not broker Karzai's talks with Haqqani". Dawn. 2 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Militant Networks in North Waziristan". OutlookAfghanistan.net. 26 May 2011. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen (21 September 2011). "U.S. sharpens warning to Pakistan". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Pakistan 'backed Haqqani attack on Kabul' – Mike Mullen". BBC. 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "Pakistan condemns US comments about spy agency". Associated Press. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Clinton Presses Pakistan to Help Fight Haqqani Insurgent Group". Fox News. 18 September 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "U.S. blames Pakistan agency in Kabul attack". Reuters. 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "U.S. links Pakistan to group it blames for Kabul attack". Reuters. 17 September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "Obama won't back Mullen's claim on Pakistan". NDTV. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Newspaper, the (21 October 2011). "Clinton demands action in 'days and weeks'". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Defiant Pak refuses to go after Haqqanis". The Times of India. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "CIA created Haqqani network: Rehman Malik". Dawn. 25 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Haqqani network created by the CIA: Rehman Malik". The Tribune. 25 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "CIA, not Pakistan, created Haqqani network: Malik". The News. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Brittle relations: Islamabad 'vehemently' rejects US 'proxy war' claims". The Express Tribune. 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Zirulnick, Ariel. "Pakistan refuses to battle Haqqani network." Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Christian Science Monitor, 26 September 2011.

- ^ "US seeks Pak aid in peace efffort". The News International, Pakistan. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "US commander commends Zarb-e-Azb for disrupting Haqqani network's ability to target Afghanistan". Express News. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Borger, Julian (17 August 2020). "Iran reportedly paid bounties to Afghan group for attacks on Americans". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Iran denies paying Taliban to target US troops, calls reports propaganda". Al Arabiya English. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Haqqani's son killed in Paktia, The News International, 11 July 2008

- ^ "Rewards For Justice: Sirajuddin Haqqani". U.S. State Department. 14 January 2008. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "US Senator: Label Pakistan Taliban, Haqqani, as terrorists". Agence France-Presse. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (14 June 2010). "US, Afghan Forces Kill Haqqani Network Commander During Raid in Khost". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "Afghan, International Force Clears Haqqani Stronghold". ISAF. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ a b Nichols, Michelle (22 July 2011). "NATO kills 50 fighters, clears Afghan training camp". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Rare glimpse into U.S. special operations forces in Afghanistan". Security Clearance (blog). CNN. 26 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

U.S. and Afghan troops attacked an insurgent encampment, killing nearly 80 foreign fighters…. The camp they attacked and the fighters there were part of the so-called Haqqanni network, which is responsible for many recent attacks in Afghanistan and is closely tied to al Qaeda. The Haqqanis traditionally rely on Afghan and Pakistani fighters, but in this instance most of the fighters there who were killed were Arabs and Chechens, brought into Afghanistan from Pakistan.

- ^ "US drones strike in North, South Waziristan". The Express Tribune. The Express Tribune News Network. 13 October 2011. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ a b Mashal, Mujib (25 October 2011). "Afghan forces target Haqqani strongholds". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ Sharifzada, Jawad (18 October 2011). "Push launched against Haqqanis in border areas". pajhwok.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Yousaf, Kamran (2 November 2011). "Pakistan looks to restrict Haqqanis' movement". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Tyrone C. Jr. "Objectives Achievable Despite Pakistan Sanctuaries, General Says." American Forces Press Service, 27 October 2011.

- ^ "Controversial US drone attack in Pakistan, 16 killed". Pakistan News.Net. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Operation Zarb-i-Azb disrupted Haqqani network: US general". Dawn. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "US senators link Pakistan aid to Haqqani crackdown". BBC. 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "Summary: FY12 State, Foreign Operations Appropriations Bill". U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "US designates Haqqani group as 'terrorists'". Al Jazeera. 7 September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen (7 September 2012). "Haqqani network to be designated a terrorist group". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "UN adds Haqqani network to Taliban sanctions list". BBC News. 5 November 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "About the listing process". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Proscribed Terrorist Organisations Archived 7 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine UK Home Office.

- ^ "Aziz Haqqani". Rewards for Justice. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Abdul Aziz Haqqani Designated Global Terrorist". Voice of America. 7 September 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Hillary Clinton: US held meeting with Haqqani network". BBC News. 21 October 2011. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; David E. Sanger (30 October 2011). "U.S. Seeks Aid From Pakistan in Peace Effort". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 October 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Rassler, Don; Vahid Brown (2013). Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Nexus, 1973–2012 (1st ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231704380. OCLC 794366385.

- Van Dyk, Jere (2022). Without Borders: The Haqqani Network and the Road to Kabul. Washington, D.C.: Academica Press. ISBN 9781680538656. OCLC 1302578352.

External links

[edit]- The Haqqani Network (PDF), by Jeffrey A. Dressler, Institute for the Study of War

- Haqqani Network, GlobalSecurity.org

- Haqqani Network, Institute for the Study of War

- Sirajuddin Haqqani, Rewards for Justice Program

- Haqqanis: Growth of a militant network, BBC News, 14 September 2011

- Q&A: Who are the Haqqanis?, Reuters

- Haqqani network collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Haqqani Network Financing: The Evolution of an Industry Archived 16 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine – The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, July 2012

- The Haqqani History: Bin Ladin's Advocate inside the Taliban – National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, 11 September 2012

- Anti-Soviet factions in the Soviet–Afghan War

- Haqqani network

- Islamist groups

- Islamic terrorism in Afghanistan

- Jihadist groups in Afghanistan

- Jihadist groups in Pakistan

- Organizations based in Asia designated as terrorist

- Organizations designated as terrorist by Canada

- Organizations designated as terrorist by the United States

- Organisations designated as terrorist by the United Kingdom