Marvin Gaye

Marvin Gaye | |

|---|---|

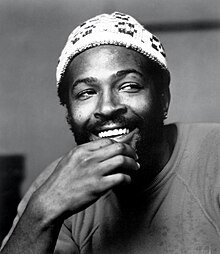

Gaye in 1973 | |

| Born | Marvin Pentz Gay Jr. April 2, 1939 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | April 1, 1984 (aged 44) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1957–1984 |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3, including Nona |

| Parents | |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Marvin Gaye discography |

| Labels | |

Marvin Pentz Gaye Jr. (né Gay; April 2, 1939 – April 1, 1984)[1] was an American singer-songwriter and musician. He helped shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, first as an in-house session player and later as a solo artist with a string of successes, which earned him the nicknames "Prince of Motown" and "Prince of Soul".

Gaye's Motown hits include "How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You)" (1964), "Ain't That Peculiar" (1965), and "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" (1968). He also recorded duets with Mary Wells, Kim Weston, Tammi Terrell, and Diana Ross. During the 1970s, Gaye became one of the first Motown artists to break away from the reins of a production company and recorded the landmark albums What's Going On (1971) and Let's Get It On (1973).

His later recordings influenced several R&B subgenres, such as quiet storm and neo soul.[2] "Sexual Healing", released in 1982 on the album Midnight Love, won him his first two Grammy Awards.[3] Gaye's last televised appearances were at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, where he sang "The Star-Spangled Banner", Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever in 1983, and on Soul Train.[4]

On April 1, 1984, the day before his 45th birthday, Gaye was shot and killed by his father, Marvin Gay Sr., at their house in Western Heights, Los Angeles,[5][6] after an argument. Gay Sr. later pleaded no contest to voluntary manslaughter, and received a six-year suspended sentence and five years of probation. Many institutions have posthumously bestowed Gaye with awards and other honors including the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and inductions into the Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[7]

Early life

[edit]Marvin Pentz Gay Jr. was born on April 2, 1939, at Freedman's Hospital[8] in Washington, D.C., to church minister Marvin Gay Sr. and domestic worker Alberta Gay (née Cooper). His first home was in a public housing project,[9] the Fairfax Apartments[10] (now demolished) at 1617 1st Street SW in the Southwest Waterfront neighborhood.[11] Although one of the city's oldest neighborhoods, with many elegant Federal-style homes, most buildings were small, in extensive disrepair, and lacked both electricity and running water. The alleys were full of one- and two-story shacks, and nearly every dwelling was overcrowded.[12][13][14] Gaye and his friends nicknamed the area "Simple City", owing to it being "half-city, half country".[15][16][a]

Gaye was the second oldest of the couple's four children. He had two sisters, Jeanne and Zeola, and one brother, Frankie Gaye. He also had two half-brothers: Michael Cooper, his mother's son from a previous relationship, and Antwaun Carey Gay,[18] born as a result of one of his father's extramarital affairs.[18]

Gaye started singing in church when he was four years old; his father often accompanied him on piano.[19][20][21] Gaye and his family were part of a conservative church known as the House of God that took its teachings from Pentecostalism, with a strict code of conduct.[22][23] Gaye developed a love of singing at an early age and was encouraged to pursue a professional music career after a performance at a school play at 11 singing Mario Lanza's "Be My Love".[21] His home life consisted of "brutal whippings" by his father, who struck him for any shortcoming.[24] The young Gaye described living in his father's house as similar to "living with a king, a very peculiar, changeable, cruel, and all powerful king".[15] He felt that had his mother not consoled him and encouraged his singing, he would have committed suicide.[25] His sister later explained that Gaye was beaten often, from age seven well into his teenage years.[26]

Gaye attended Syphax Elementary School[27] and then Randall Junior High School.[28][29] Gaye began to take singing much more seriously in junior high,[30] and he joined and became a singing star with the Randall Junior High Glee Club.[10]

In 1953[9][31][32] or 1954,[8][33][b] the Gays moved into the East Capitol Dwellings public housing project in D.C.'s Capitol View neighborhood.[8][35][c] Their townhouse apartment (Unit 12, 60th Street NE; now demolished) was Marvin's home until 1962.[34][d]

Gaye briefly attended Spingarn High School before transferring to Cardozo High School.[36] At Cardozo, Gaye joined several doo-wop vocal groups, including the Dippers and the D.C. Tones.[38] During his teenage years, his father would kick him out of the house often.[39] In 1956, 17-year-old Gaye dropped out of high school and enlisted in the United States Air Force as an airman basic.[40][41] His early disenchantment with the service was similar to most of his peers who were made to perform menial labor, not working on jet airplanes as hoped. Gaye later said he lost his virginity to a local prostitute while in the Air Force. He feigned mental illness and was given a "General Discharge", with an outgoing performance review from his sergeant remarking "Airman Gay cannot adjust to regimentation nor authority".[42][43]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]After Gaye left the Air Force, he formed a vocal quartet, The Marquees, with his good friend Reese Palmer.[44][45] The group performed in the D.C. area and soon began working with Bo Diddley, who tried to persuade his own label, Chess, to sign them to a record deal. Failing that, he sent them to Columbia subsidiary OKeh Records.[45] Diddley co-wrote the group's sole single, "Wyatt Earp"; it failed to chart and the group was soon dropped from the label.[46] Gaye began composing music.[46]

Moonglows co-founder Harvey Fuqua later hired The Marquees as employees.[47] Under Fuqua's direction, the group changed its name to Harvey and the New Moonglows, and moved to Chicago.[48] The group recorded several sides for Chess in 1959, including the song "Mama Loocie", which was Gaye's first lead vocal recording.[citation needed] The group found work as session singers for established acts such as Chuck Berry, singing on the songs "Back in the U.S.A." and "Almost Grown".[49]

In 1960, the group disbanded. Gaye moved to Detroit with Fuqua, where he signed with Tri-Phi Records as a session musician, playing drums on several Tri-Phi releases. Gaye performed at Motown president Berry Gordy's house during the holiday season in December 1960. Impressed, Gordy sought Fuqua on his contract with Gaye. Fuqua agreed to sell part of his interest in his contract with Gaye.[50] Shortly afterwards, Gaye signed with Motown subsidiary Tamla.[citation needed]

When Gaye signed with Tamla, he pursued a career as a performer of jazz music and standards, having no desire to become an R&B performer.[39] Before the release of his first single, Gaye started spelling his surname with added "e", in the same way as did Sam Cooke. Author David Ritz wrote that Gaye did this to silence rumors of his sexuality, and to put more distance between himself and his father.[51]

Gaye released his first single, "Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide", in May 1961, with the album The Soulful Moods of Marvin Gaye, following a month later. Gaye's initial recordings failed commercially and he spent most of 1961 performing session work as a drummer for artists such as The Miracles, The Marvelettes and blues artist Jimmy Reed for $5 (US$51 in 2023 dollars[52]) a week.[53][54] While Gaye took some advice on performing with his eyes open (having been accused of appearing as though he were sleeping) and also got pointers on how to move more gracefully onstage, he refused to attend grooming school courses at the John Robert Powers School for Social Grace in Detroit because of his unwillingness to comply with its orders, something he later regretted.[55][56]

Initial success

[edit]In 1962, Gaye found success as co-writer of the Marvelettes track "Beechwood 4-5789", on which he also played drums. His first solo success, "Stubborn Kind of Fellow", was later released that September, reaching No. 8 on the R&B chart and No. 46 on the Billboard Hot 100. Gaye first reached the pop top 40 with the dance song, "Hitch Hike",[57] peaking at No. 30 on the Hot 100. "Pride and Joy" became Gaye's first top ten single after its release in 1963.[citation needed]

The three singles and songs from the 1962 sessions were included on Gaye's second album, That Stubborn Kinda Fellow, released on Tamla in January 1963. Starting in October 1962, Gaye performed as part of the Motortown Revue, a series of concert tours headlined at the north and southeastern coasts of the United States as part of the Chitlin' Circuit, a series of rock shows performed at venues that welcomed predominantly black musicians. A filmed performance of Gaye at the Apollo Theater took place in June 1963. Later that October, Tamla issued the live album, Marvin Gaye Recorded Live on Stage. "Can I Get a Witness" became one of Gaye's early international successes.[citation needed]

In 1964, Gaye recorded a successful duet album with singer Mary Wells titled Together, which reached No. 42 on the pop album chart. The album's two-sided single, including "Once Upon a Time" and 'What's the Matter With You Baby", each reached the top 20. Gaye's next solo success, "How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)", which Holland-Dozier-Holland wrote for him, reached No. 6 on the Hot 100 and reached the top 50 in the UK. Gaye started getting television exposure around this time, on shows such as American Bandstand. Also in 1964, he appeared in the concert film The T.A.M.I. Show. Gaye had two number-one R&B singles in 1965 with the Miracles–composed "I'll Be Doggone" and "Ain't That Peculiar". Both songs became million-sellers. After this, Gaye returned to jazz-derived ballads for a tribute album to the recently-deceased Nat "King" Cole.[58]

After recording "It Takes Two" with Kim Weston, Gaye began working with Tammi Terrell on a series of duets, mostly composed by Ashford & Simpson, including "Ain't No Mountain High Enough", "Your Precious Love", "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing" and "You're All I Need to Get By".[citation needed]

In October 1967, Terrell collapsed in Gaye's arms during a performance in Farmville, Virginia.[59] Terrell was subsequently rushed to Farmville's Southside Community Hospital, where doctors discovered she had a malignant tumor in her brain.[59] The diagnosis ended Terrell's career as a live performer, though she continued to record music under careful supervision. Despite the presence of successful singles such as "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing" and "You're All I Need to Get By", Terrell's illness caused problems with recording, and led to multiple operations to remove the tumor. Gaye was reportedly devastated by Terrell's sickness and became disillusioned with the record business.[citation needed]

On October 6, 1968, Gaye sang the national anthem during Game 4 of the 1968 World Series, held at Tiger Stadium, in Detroit, Michigan, between the Detroit Tigers and the St. Louis Cardinals.[60]

In late 1968, Gaye's recording of "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" became his first to reach No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. It also reached the top of the charts in other countries, selling over four million copies.[61] However, Gaye felt the success was something he "didn't deserve" and that he "felt like a puppet – Berry's puppet, Anna's puppet".[62][63][64] Gaye followed it up with "Too Busy Thinking About My Baby" and "That's the Way Love Is", which reached the top ten on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1969. That year, his album M.P.G. became his first No. 1 album on the R&B album charts. During this period, Gaye produced and co-wrote "Baby I'm For Real" and "The Bells" for The Originals.[citation needed]

Tammi Terrell died from brain cancer on March 16, 1970; Gaye attended her funeral[65] and after a period of depression, Gaye sought out a position on a professional football team, the Detroit Lions, where he later befriended Mel Farr and Lem Barney.[66] Barney and Farr had gotten gold records for providing backup vocals for the title track of Gaye's What's Going On album. The Lions played along for the publicity, but ultimately declined an invitation for Gaye to try out, owing to legal liabilities and fears of possible injuries that could have affected his music career.[67][68]

What's Going On and subsequent success

[edit]On June 1, 1970, Gaye returned to Hitsville U.S.A., where he recorded his new composition "What's Going On", inspired by an idea from Renaldo "Obie" Benson of the Four Tops after he witnessed an act of police brutality at an anti-war rally in Berkeley.[69] Upon hearing the song, Berry Gordy refused its release due to his feelings of the song being "too political" for radio and feared Gaye would lose his crossover audience.[70] Gaye responded by deciding against releasing any other new material before the label released it.[70] Released in 1971, it reached No. 1 on the R&B charts within a month, staying there for five weeks. It also reached the top spot on Cashbox's pop chart for a week and reached No. 2 on the Hot 100 and the Record World chart, selling over two million copies.[71][72]

After giving an ultimatum to record a full album to win creative control from Motown, Gaye spent ten days recording the What's Going On album that March.[73] Motown issued the album that May after Gaye remixed the album in Hollywood.[70] The album became Gaye's first million-selling album launching two more top ten singles, "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)" and "Inner City Blues". One of Motown's first autonomous works, its theme and segue flow brought the concept album format to rhythm and blues and soul music. An AllMusic writer later cited it as "the most important and passionate record to come out of soul music, delivered by one of its finest voices".[74] For the album, Gaye received two Grammy Award nominations at the 1972 ceremony and several NAACP Image Awards.[75] The album also topped Rolling Stone's year-end list as its album of the year. Billboard magazine named Gaye "Trendsetter of the Year" following the album's success.[citation needed]

In 1971, Gaye signed a new deal with Motown worth $1 million (US$7,523,418 in 2023 dollars[52]), making it the most lucrative deal by a black recording artist at the time.[76] Gaye first responded to the new contract with the soundtrack and subsequent score, Trouble Man, released in late 1972. Before the release of Trouble Man, Marvin released a single called "You're the Man". The album of the same name was a follow-up to What's Going On, but Motown refused to promote the single, according to Gaye. According to some biographies,[which?] Gordy, who was considered a moderate, feared Gaye's left-leaning political views would alienate Motown's moderately liberal audiences. As a result, Gaye shelved the project and substituted it for Trouble Man. In 2019, Universal Music Group released the album on what would've been Gaye's 80th birthday.[77] In between the releases of What's Going On and Trouble Man, Gaye and his family relocated to Los Angeles, making Marvin one of the final Motown artists to move there despite early protests urging him to stay in Detroit.[citation needed]

In August 1973, Gaye released the Let's Get It On album. Its title track became Gaye's second No. 1 single on the Hot 100. The album was later hailed as "a record unparalleled in its sheer sensuality and carnal energy".[78] Other singles from the album included "Come Get to This", which recalled Gaye's early Motown soul sound of the previous decade, while the suggestive "You Sure Love to Ball" reached modest success on the R&B charts, while also managing to make the pop top 50, its success halted by radio refusing to play the sexually explicit song.[79]

In the 1970s, Gaye's sister-in-law turned her attention to Frankie Beverly, the founder of Maze. Marvin took them on his tours, featured them as the opening acts of his concerts, and persuaded Beverly to change the band's name from Raw Soul to Maze.[citation needed]

Marvin's final duet project, Diana & Marvin, with Diana Ross, garnered international success despite contrasting artistic styles. Much of the material was crafted especially for the duo by Ashford and Simpson.[80] Responding to demand from fans and Motown, Gaye started his first concert tour in four years at the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum on January 4, 1974.[81] The performance received critical acclaim and resulted in the release of the live album, Marvin Gaye Live! and its single, a live version of "Distant Lover", an album track from Let's Get It On.[citation needed]

The tour helped to enhance Gaye's reputation as a live performer.[81] For a time, he was earning $100,000 a night (US$617,814 in 2023 dollars[52]) for performances.[82] Gaye toured throughout 1974 and 1975. A renewed contract with Motown allowed Gaye to build his own custom-made recording studio.[citation needed]

In October 1975, Gaye gave a performance at a UNESCO benefit concert at New York's Radio City Music Hall to support UNESCO's African literacy drive, resulting in him being commended at the United Nations by then-Ambassador to Ghana Shirley Temple Black and Kurt Waldheim.[83][84] Gaye's next studio album, I Want You, followed in March 1976 with the title track "I Want You" reaching No. 1 on the R&B charts. The album would go on to sell over one million copies. That spring, Gaye embarked on his first European tour in a decade, starting off in Belgium. In early 1977, Gaye released the live album, Live at the London Palladium, which sold over two million copies thanks to the success of its studio song, "Got to Give It Up", which charted at No. 1. In September 1977, Gaye opened Radio City Music Hall's New York Pop Arts Festival.[85]

Last Motown recordings and European exile

[edit]In December 1978, Gaye released Here, My Dear, inspired by the fallout from his first marriage to Anna Gordy. Recorded with the intention of remitting a portion of its royalties to her as alimony payments, it performed poorly on the charts.[86] During that period, Gaye's cocaine addiction intensified while he was dealing with several financial issues with the IRS. These issues led him to move to Maui, where he struggled to record a disco-influenced album titled Love Man, with a probable release date for February 1980, though he would later shelve the project.[87] That year, Gaye went on a European tour, his first in four years.[88] By the time the tour stopped, he had relocated to London when he feared imprisonment for failure to pay back taxes, which had now reached upwards of $4.5 million (US$16,640,549 in 2023 dollars[52]).[88][89]

Gaye then reworked Love Man from its original disco concept to another socially-conscious album invoking religion and the possible end time from a chapter in the Book of Revelation.[90] Titling the album In Our Lifetime?, Gaye worked on the album for much of 1980 in London studios such as AIR and Odyssey Studios.[91]

In the fall of that year, a master tape of a rough draft of the album was stolen from one of Gaye's traveling musicians, Frank Blair, and taken to Motown's Hollywood headquarters.[92] Motown remixed the album and released it on January 15, 1981.[93] When Gaye learned of its release, he accused Motown of editing and remixing the album without his consent, allowing the release of an unfinished production ("Far Cry"), altering the cover art and removing the album title's question mark, muting its irony.[94] He also accused the label of rush-releasing the album, comparing his unfinished album to an unfinished Pablo Picasso painting.[94] Gaye then vowed not to record any more music for Motown.[95]

On February 14, 1981, under the advice of music promoter Freddy Cousaert, Gaye relocated to Cousaert's apartment in Ostend, Belgium.[96] While there, Gaye shied away from heavy drug use and began exercising and attending a local Ostend church, regaining personal confidence.[97][98] In this period, Gaye lived in the home of Belgian musician Charles Dumolin. In March 2024, it was revealed that when he moved on, Gaye had given the family a large collection of unreleased recordings made during his stay in the country.[99]

Following several months of recovery, Gaye sought a comeback onstage, starting the short-lived Heavy Love Affair tour in England and Ostend in June–July 1981.[100] Gaye's personal attorney Curtis Shaw would later describe Gaye's Ostend period as "the best thing that ever happened to Marvin". When word got around that Gaye was planning a musical comeback and an exit from Motown, CBS Urban president Larkin Arnold eventually was able to convince Gaye to sign with CBS Records. On March 23, 1982, Motown and CBS negotiated Gaye's release from Motown. The details of the contract were not revealed due to a possible negative effect on Gaye's settlement to creditors from the IRS and to stop a possible bidding war by competing labels.[101]

Midnight Love

[edit]Assigned to CBS's Columbia subsidiary, Gaye worked on his first post-Motown album titled Midnight Love. The first single from the album, "Sexual Healing", which was written and recorded in Ostend in Freddy Cousaert's apartment, was released in October 1982, and became Gaye's biggest career success, spending a record 10 weeks at No. 1 on the Hot Black Singles chart, becoming the biggest R&B hit of the 1980s according to Billboard stats. In January 1983, it successfully crossed over to the Billboard Hot 100, where it peaked at No. 3, while the record reached international success, reaching the top spot in New Zealand and Canada and reaching the top 10 on the United Kingdom's OCC singles chart, Australia and Belgium, later selling more than two million copies in the U.S. alone, becoming Gaye's most successful single to date. The video for the song was shot at Ostend's Casino-Kursaal.[102]

"Sexual Healing" won Gaye his first two Grammy Awards including Best Male R&B Vocal Performance, in February 1983, and also won Gaye an American Music Award in the R&B-soul category. People magazine called it "America's hottest musical turn-on since Olivia Newton-John demanded we get 'Physical'". Midnight Love was released to stores less than a month after the single's release, and was equally successful, peaking at the top 10 of the Billboard 200 and becoming Gaye's eighth No. 1 album on the Top Black Albums chart, eventually selling three million alone in the U.S.[citation needed]

I don't make records for pleasure. I did when I was a younger artist, but I don't today. I record so that I can feed people what they need, what they feel. Hopefully, I record so that I can help someone overcome a bad time.

On February 13, 1983, Gaye sang "The Star-Spangled Banner" at the NBA All-Star Game at The Forum in Inglewood, California—accompanied by Gordon Banks, who played the studio tape from the stands.[4] The following month, Gaye performed at the Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever special. This and a May appearance on Soul Train (his third appearance on the show) became Gaye's final television performances. Gaye embarked on his final concert tour, titled the Sexual Healing Tour, on April 18, 1983, at The El Cortez Hotel Concerts by the Bay in San Diego.[104] The tour, which had 51 dates in total and included a then-record six sold-out shows at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, ended on August 14, 1983, at the Pacific Amphitheatre in Costa Mesa, California, but was plagued by cocaine-triggered paranoia and illness. Following the concert's end, he moved into his parents' house in Los Angeles. In early 1984, Midnight Love was nominated for a Grammy in the Best Male R&B Vocal Performance category, his 12th and final nomination.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

In June 1963, Gaye married Anna Gordy, sister to Berry Gordy. The couple separated in 1973, and Gordy filed for divorce in November 1975. The couple officially divorced in 1977. Gaye later married Janis Hunter in October 1977. The couple separated in 1979 and officially divorced in November 1982.

Gaye was the father of three children: Marvin III, Nona, and Frankie. Marvin III was the biological son of Anna's niece, Denise Gordy, who was 16 at the time of the birth. Nona and Frankie were born to Gaye's second wife, Janis. At the time of his death, Gaye was survived by his three children, mother, father, and five siblings.

Gaye was a cousin of Wu-Tang Clan member Masta Killa.[105]

Death

[edit]

In the early afternoon of April 1, 1984, Gaye intervened in a fight between his parents in the family house in the West Adams neighborhood of Western Heights[5] in Los Angeles. He became involved in a physical altercation with his father, Marvin Gay Sr.,[106] who shot Gaye twice, once in the chest, piercing his heart, and then into his shoulder.[106] The shooting took place in Gaye's bedroom at 12:38 p.m. Gaye was pronounced dead at 1:01 p.m. after his body arrived at California Hospital Medical Center, the day before his 45th birthday.[106][107]

After Gaye's funeral, his body was cremated at Forest Lawn Memorial Park–Hollywood Hills, and his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean.[108][109] Gay Sr. was initially charged with first-degree murder, but the charges were reduced to voluntary manslaughter following a diagnosis of a brain tumor.[110] He was given a suspended six-year sentence and probation. He died at a nursing home in 1998.[111]

Musicianship

[edit]Equipment

[edit]Starting off his musicianship as a drummer doing session work during his tenure with Harvey Fuqua, and his early Motown years, Gaye's musicianship evolved to include piano, keyboards, synthesizers, and organ. Gaye also used percussion instruments, such as bells, finger cymbals, box drums, glockenspiels, vibraphones, bongos, congas, and cabasas. This became evident when he was given creative control in his later years with Motown, to produce his own albums. In addition to his talent as a drummer, Gaye also embraced the TR-808, a drum machine that became prominent in the early '80s, making use of its sounds for production of his Midnight Love album. The piano was his primary instrument when performing on stage, with occasional drumming.[112]

Influences

[edit]As a child, Gaye's main influence was his minister father, something he later acknowledged to biographer David Ritz, and also in interviews, often mentioning that his father's sermons greatly impressed him. His first major musical influences were doo-wop groups such as The Moonglows and The Capris. Gaye's Rock & Roll Hall of Fame page lists the Capris' song, "God Only Knows" as "critical to his musical awakening".[113] Of the Capris' song, Gaye said, "It fell from the heavens and hit me between the eyes. So much soul, so much hurt. I related to the story, to the way that no one except the Lord really can read the heart of lonely kids in love."[114] Gaye's main musical influences were Rudy West of The Five Keys, Clyde McPhatter, Ray Charles and Little Willie John.[115] Gaye considered Frank Sinatra a major influence in what he wanted to be.[116] He also was influenced by the vocal styles of Billy Eckstine and Nat King Cole.[117]

As his Motown career developed, Gaye took inspiration from fellow label mates such as David Ruffin of The Temptations and Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops, whose grittier voices led to Gaye and his producer seeking a similar sound in recordings such as "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" and "That's the Way Love Is". Later in his life, Gaye reflected on the influence of Ruffin and Stubbs, stating: "I had heard something in their voices something my own voice lacked."[118] He further explained, "the Tempts and Tops' music made me remember that when a lot of women listen to music, they want to feel the power of a real man."[118]

Vocal style

[edit]Gaye had a four-octave vocal range.[119] From his earlier recordings as member of the Marquees and Harvey and the New Moonglows, and in his first several recordings with Motown, Gaye recorded mainly in the baritone and tenor ranges. He changed his tone to a rasp for his gospel-inspired early hits such as "Stubborn Kind of Fellow" and "Hitch Hike". As writer Eddie Holland explained, "He was the only singer I have ever heard known to take a song of that nature, that was so far removed from his natural voice where he liked singing, and do whatever it took to sell that song."[120]

In songs such as "Pride and Joy", Gaye used three different vocal ranges—singing in his baritone range at the beginning, bringing a lighter tenor in the verses before reaching a gospel mode in the chorus. Holland further stated of Gaye's voice that it was "one of the sweetest and prettiest voices you ever wanted to hear".[121] And while he noted that ballads and jazz was "his basic soul", he stated Gaye "had the ability to take a roughhouse, rock and roll, blues, R&B, any kind of song and make it his own", later saying that Gaye was the most versatile vocalist he had ever worked with.[121]

Gaye changed his vocal style in the late 1960s, when he was advised to use a sharper, raspy voice—especially in Norman Whitfield's recordings. Gaye initially disliked the new style, considering it out of his range, but said he was "into being produce-able".[122] After listening to David Ruffin and Levi Stubbs, Gaye said he started to develop what he called his "tough man voice"—saying, "I developed a growl."[118] In the liner notes of his DVD set, Marvin Gaye: The Real Thing in Performance 1964–1981, Rob Bowman said that by the early 1970s, Gaye had developed "three distinct voices: his smooth, sweet tenor; a growling rasp; and an unreal falsetto."[123] Bowman further wrote that the recording of the What's Going On single was "...the first single to use all three as Marvin developed a radical approach to constructing his recordings by layering a series of contrapuntal background vocal lines on different tracks, each one conceived and sung in isolation by Marvin himself."[123] Bowman found that Gaye's multi-tracking of his tenor voice and other vocal styles "summon[ed] up what might be termed the ancient art of weaving".[123]

Social commentary and concept albums

[edit]Prior to recording the What's Going On album, Gaye recorded a cover of the song, "Abraham, Martin & John", which became a UK hit in 1970. Despite some political music and socially conscious material recorded by The Temptations, Motown artists were often told to not delve into political and social commentary, for fear of alienating pop audiences. Early in his career, Gaye was affected by social events such as the 1965 Watts riots and once asked himself: "with the world exploding around me, how am I supposed to keep singing love songs?"[124] When Gaye called Gordy in the Bahamas about wanting to do protest music, Gordy told him: "Marvin, don't be ridiculous. That's taking things too far."[73]

Gaye was inspired by the Black Panther Party and supported the efforts they put forth such as giving free meals to poor families door to door. However, he did not support the violent tactics the Panthers used to fight oppression, as Gaye's messages in many of his political songs were nonviolent. The lyrics and music of What's Going On discuss and illustrate issues during the 1960s/1970s such as racism, police brutality, drug abuse, environmental issues, anti-war, and black power issues.[125] Gaye was inspired to make this album because of events such as the Vietnam War, the 1967 race riots in Detroit, and the Kent State shootings, as well as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.[126]

Once Gaye presented Gordy with the What's Going On album, Gordy feared Gaye was risking the ruination of his image as a sex symbol.[70] Following the album's success, Gaye tried a follow-up album, You're the Man. The title track only produced modest success, however, and Gaye and Motown shelved the album. Several of Gaye's unreleased songs of social commentary, including "The World Is Rated X", would be issued on posthumous compilation albums. What's Going On would later be described by an AllMusic writer as an album that "not only redefined soul music as a creative force but also expanded its impact as an agent for social change".[127] You're the Man was finally released on March 29, 2019, through Motown, Universal Music Enterprises, and Universal Music Group.[128]

The What's Going On album also provided another first in both Motown and R&B music: Gaye and his engineers had composed the album in a song cycle, segueing previous songs into other songs giving the album a more cohesive feel as opposed to R&B albums that traditionally included filler tracks to complete the album. This style of music would influence recordings by artists such as Stevie Wonder and Barry White making the concept album format a part of 1970s R&B music. Concept albums are usually based on either one theme or a series of themes in connection to the original thesis of the album's concept. Let's Get It On repeated the suite-form arrangement of What's Going On, as would Gaye's later albums such as I Want You, Here, My Dear and In Our Lifetime.[citation needed] Although Gaye was not politically active outside of his music, he became a public figure for social change and inspired/educated many people through his work.[126]

Legacy

[edit]Gaye has been called "the number-one purveyor of soul music".[19] In his book Mercy Mercy Me: The Art, Loves and Demons of Marvin Gaye, Michael Eric Dyson described Gaye as someone "who transcended the boundaries of rhythm and blues as no other performer had done before".[129] Following his death, The New York Times described Gaye as someone who "blended the soul music of the urban scene with the beat of the old-time gospel singer and became an influential force in pop music".[130] Further in the article, Gaye was also credited with combining "the soulful directness of gospel music, the sweetness of soft-soul and pop, and the vocal musicianship of a jazz singer".[130] His recordings for Motown in the 1960s and 1970s shaped that label's signature sound. His work with Motown gave him the titles Prince of Soul and Prince of Motown.[131][132] Critics stated that Gaye's music "signified the development of black music from raw rhythm and blues, through sophisticated soul to the political awareness of the 1970s and increased concentration on personal and sexual politics thereafter".[133] As a Motown artist, Gaye was among the first to break from the reins of its production system, paving the way for Stevie Wonder.[19][134][135][136] Gaye's late 1970s and early 1980s recordings influenced forms of R&B predating the subgenres quiet storm and neo-soul.[2]

Barry White, Stevie Wonder, Frankie Beverly and many others have said they were influenced by Gaye's music. For his Oscar-nominated role as James "Thunder" Ealy in the film Dreamgirls, Eddie Murphy replicated Gaye's 1970s clothing style.[citation needed]

David Ritz wrote in a 1991 revision of his biography of Gaye, "since 1983, Marvin's name has been mentioned—in reverential tones—on no less than seven top-ten hit records."[132] Gaye's name has been used in the title of several hits, including Big Sean's "Marvin Gaye & Chardonnay" and Charlie Puth's debut hit, "Marvin Gaye", a duet with Meghan Trainor. The 1983 Spandau Ballet hit "True" mentions "Listening to Marvin all night long...".[citation needed]

Awards and honors

[edit]The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted him in 1987, declaring that Gaye "made a huge contribution to soul music in general and the Motown Sound in particular". The page stated that Gaye "possessed a classic R&B voice that was edged with grit yet tempered with sweetness". The page further states that Gaye "projected an air of soulful authority driven by fervid conviction and heartbroken vulnerability".[113] A year after his death, then-mayor of D.C., Marion Barry declared April 2 as "Marvin Gaye Jr. Memorial Scholarship Fund Day" in the city.[137] Since then, a non-profit organization has helped to organize annual Marvin Gaye Day Celebrations in the city of Washington.[138]

A year later, Gaye's mother founded the Marvin P. Gaye Jr. Memorial Foundation in dedication to her son to help those suffering from drug abuse and alcoholism; however she died a day before the memorial was set to open in 1987.[139] Gaye's sister Jeanne once served as the foundation's chairperson.[140] In 1988, a year after his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, Gaye was inducted posthumously to the NAACP Hall of Fame. In 1990, Gaye received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[141][142] In 1996, Gaye posthumously received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame listed three Gaye recordings, "I Heard It Through the Grapevine", "What's Going On" and "Sexual Healing", among its list of the 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll.[143] American music magazine Rolling Stone ranked Gaye No. 18 on their list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time",[144] sixth on their list of "100 Greatest Singers of All Time"[145] and number 82 on their list of the "100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time".[146] Q magazine ranked Gaye sixth on their list of the "100 Greatest Singers".[147]

Three of Gaye's albums – What's Going On (1971), Let's Get It On (1973), and Here, My Dear (1978) – were ranked by Rolling Stone on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. What's Going On remains his largest-ranked album, reaching No. 6 on the Rolling Stone list and topped the NME list of the Top 100 Albums of All Time in 1985[148] and was later chosen in 2003 for inclusion by the Library of Congress to its National Recording Registry.[149] In a revised 2020 Rolling Stone list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, What's Going On was listed as the greatest album of all time. In addition, four of his songs – "I Heard It Through the Grapevine", "What's Going On", "Let's Get It On" and "Sexual Healing" – made it on the Rolling Stone list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[citation needed] In 2005, Gaye was voted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame.[150]

In 2006, Watts Branch Park, a park in Washington that Gaye frequented as a teenager, was renamed Marvin Gaye Park.[151] Three years later, the 5200 block of Foote Street NE in Deanwood, Washington, D.C., was renamed Marvin Gaye Way.[152] In August 2014, Gaye was inducted to the official Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame in its second class.[153] In October 2015, the Songwriters Hall of Fame announced Gaye as a nominee for induction to the Hall's 2016 class after posthumous nominations were included.[154][155] Gaye was named as a posthumous inductee to that hall on March 2, 2016.[156][157] Gaye was subsequently inducted to the Songwriters Hall on June 9, 2016.[158] In July 2018, a bill by California politician Karen Bass to rename a post office in South Los Angeles after Gaye was signed into law by President Donald Trump.[159] Gaye was ranked number 20 on Rolling Stone's "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time" published in January 2023.[160]

In popular culture

[edit]His 1983 NBA All-Star performance[161] of the national anthem was used in a Nike commercial featuring the 2008 U.S. Olympic basketball team. Also, on CBS Sports' final NBA telecast to date (before the contract moved to NBC) at the conclusion of Game 5 of the 1990 Finals, they used Gaye's 1983 All-Star Game performance over the closing credits. When VH1 launched on January 1, 1985, Gaye's 1983 rendition of the national anthem was the first video they aired. In 2010, it was used in the intro to Ken Burns' Tenth Inning documentary on the game of baseball.[citation needed] The 1985 Commodores song "Nightshift" was a tribute to Gaye and Jackie Wilson, who both died in 1984. One verse mentions Gaye's song "What's Going On".[citation needed]

"I Heard It Through the Grapevine" was played in a Levi's television advertisement in 1985.[162][163] The result of the commercial's success led to the original song finding renewed success in Europe after Tamla-Motown re-released it in the United Kingdom, Germany and the Netherlands.[163] In 1986, the song was covered by Buddy Miles as part of a California Raisins ad campaign.[164] The song was later used for chewing gum commercials in Finland and to promote a brand of Lucky Strike cigarettes in Germany.[165][166]

Gaye's music has also been used in numerous film soundtracks including Four Brothers and Captain America: The Winter Soldier, both of which featured Gaye's music from his Trouble Man soundtrack. "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" was used in the opening credits of the film, The Big Chill.[167][168][169]

In 2007, his song "A Funky Space Reincarnation" was used in the Charlize Theron–starred ad for Dior J'Adore perfume. A documentary about Gaye—What's Going On: The Marvin Gaye Story—was a UK/PBS co-production, directed by Jeremy Marre and was first broadcast in 2006. Two years later, the special re-aired with a different production and newer interviews after it was re-broadcast as an American Masters special. Another documentary, focusing on his 1981 documentary, Transit Ostend, titled Remember Marvin, aired in 2006.[citation needed]

Earnings

[edit]In 2008, Gaye's estate earned $3.5 million (US$4,953,014 in 2023 dollars[52]). As a result, Gaye took 13th place in "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities" in Forbes magazine.[170]

On March 11, 2015, Gaye's family was awarded $7.4 million in damages following a decision by an eight-member jury in Los Angeles that Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams had breached copyright by incorporating part of Gaye's song "Got to Give It Up" into their hit "Blurred Lines"; U.S. District Judge John Kronstadt reduced the sum to $5.3 million, while adding royalties.[171] In January 2016, the Gaye family requested that a California judge give $2.66 million in attorneys' fees and $777,000 in legal expenses.[172]

As of 2018, Gaye's estate was managed by Geffen Management Group and his legacy is protected through Creative Rights Group. Both are founded by talent manager Jeremy Geffen.[173]

Attempted biopics

[edit]There have been several attempts to adapt Gaye's life story into a feature film. In February 2006, it was reported that Jesse L. Martin was to portray Gaye in a biopic titled Sexual Healing, named after Gaye's 1982 song of the same name. The film was to have been directed by Lauren Goodman and produced by James Gandolfini and Alexandra Ryan. The film was to depict the final three years of Gaye's life.[174][175][176][177][178] Years later, other producers such as Jean-Luc Van Damme, Frederick Bestall and Jimmy De Brabant, came aboard and Goodman was replaced by Julien Temple. Lenny Kravitz was almost slated to play Gaye. The script was to be written by Matthew Broughton. The film was to have been distributed by Focus Features and released on April 1, 2014, the thirtieth anniversary of Gaye's death.[179][180][181][182][183][184][185] This never came to fruition and it was announced that Focus Features no longer has involvement with the Gaye biopic as of June 2013.[186][187]

In June 2008, it was announced that F. Gary Gray was going to direct a biopic titled Marvin. The script was to be written by C. Gaby Mitchell and the film was to be produced by David Foster and Duncan McGillivray and co-produced by Ryan Heppe. According to Gray, the film would cover Gaye's entire life, from his emergence at Motown through his defiance of Berry Gordy to record What's Going On and on up to his death.[188][189]

Cameron Crowe had also been working on a biopic titled My Name Is Marvin. The film was to have been a Sony presentation with Scott Rudin as producer. Both Will Smith and Terrence Howard were considered for the role of Gaye. Crowe later confirmed in August 2011 that he abandoned the project: "We were working on the Marvin Gaye movie which is called My Name is Marvin, but the time just wasn't right for that movie."[190][191][192][193][194] Members of Gaye's family, such as his ex-wife Janis and his son Marvin III, have expressed opposition to a biopic.[195][196]

In July 2016, it was announced that a feature film documentary on Gaye would be released the following year delving into his life and the making of his 1971 album What's Going On. The film would be developed by Noah Media Group and Greenlight and is quoted to be "the defining portrait of this visionary artist and his impeccable album" by the film's producers Gabriel Clarke and Torquil Jones.[197] The film will include "unseen footage" of Gaye.[198] Gaye's family approved of the documentary.[197] In November 2016, it was announced that the actor Jamie Foxx was billed to produce a limited biopic series on Gaye's life.[199] The series was approved by Gaye's family, including son Marvin III, who was to serve as executive producer, and Berry Gordy, Jr.[199]

On June 18, 2018, it was reported that American rapper Dr. Dre was in talks to produce a biopic about Gaye.[200] In June 2021, it was announced that the film Dre would be producing was greenlighted by Warner Bros. Pictures and would be directed by Allen Hughes for a projected 2023 release.[201]

Acting

[edit]Gaye acted in two movies, featuring as a Vietnam veteran in both roles. His first performance was in the 1969 George McCowan film The Ballad of Andy Crocker, which starred Lee Majors. The film was about a war veteran returning to find that his expectations have not been met and he feels betrayed. Gaye had a prominent role in the film as David Owens.[202] His other performance was in 1971. He had a role in the Lee Frost-directed biker-exploitation film Chrome and Hot Leather, about a group of Vietnam veterans taking on a bike gang. The film starred William Smith; Gaye played the part of Jim, one of the veterans.[203][204]

Gaye did have acting aspirations and had signed with the William Morris Agency but that only lasted a year as Gaye was not satisfied with the support he was getting from the agency. In his interview with David Ritz, Gaye admitted being interested in show business particularly when he was hired to compose the soundtrack for Trouble Man. "No doubt I could have been a movie star, but it was something my subconscious rejected. Not that I didn't want it, I most certainly did. I just didn't have the fortitude to play the Hollywood game: to put myself out there, knowing they would eat my rear end like a piece of meat.” [205]

Discography

[edit]|

Solo studio albums

|

Collaborative albums

Posthumous albums

|

Filmography

[edit]- 1965: T.A.M.I. Show (documentary)

- 1969: The Ballad of Andy Crocker (television movie)

- 1971: Chrome and Hot Leather (television movie)

- 1973: Save the Children (documentary)

Videography

[edit]See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ This area should not be confused with the present-day Benning Terrace public housing complex in the Benning Ridge neighborhood, which today is also nicknamed "Simple City".[17]

- ^ At least once source claims they did not move in until 1955.[34]

- ^ MacKenzie and a wide range of sources mischaracterize this neighborhood as Deanwood.[32]

- ^ Some sources suggest the family first moved to the Benning Ridge neighborhood after leaving Southwest. According to Zeola Gay[36] and The Washington Post reporter Roger Catlin,[8] the Gay family moved to the Benning Terrace public housing project in the early 1950s. This is not possible, as the Benning Terrace apartments did not begin construction until late 1956,[37] a full year after Marvin Gaye had left home for the military.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Simmonds 2008, pp. 190–192.

- ^ a b Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (October 10, 1995). Spin Alternative Record Guide (Ratings 1–10) (1st edi. ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 202–205. ISBN 0-679-75574-8. OCLC 32508105.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Marvin Gaye". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. June 4, 2019. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Batchelor 2005, pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b Wedner, Diane (September 16, 2007). "Taking Over From Titans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Dial Them For Murder. January 1998. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2012 – via Los Angeles Magazine.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye Timeline". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. January 21, 1987. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Catlin, Roger (April 27, 2012). "Washington, D.C., sites with links to Marvin Gaye". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Crockett, Stephen A. Jr. (July 24, 2002). "Song of the City: In the Name of Marvin Gaye, Neighbors Rescue a Park Near His Old Home". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ a b Milloy, Courtland (April 8, 1984). "The War for One Man's Soul: Marvin Gaye". The Washington Post. p. C1, C2.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Banks & Banks 2004, p. 41.

- ^ Gutheim & Lee 2006, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Bahrampour, Tara (March 14, 2016). "'Old but not cold': Four very longtime friends anticipate turning 100 this year". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, p. 13.

- ^ Gaye 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Gillis, Justin; Miller, Bill (April 20, 1997). "In D.C.'s Simple City, Complex Rules of Life and Death". The Washington Post. p. A1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "Gaye's second wife calls play 'completely and utterly exploitative'". February 16, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.[dead link] Alt URL

- ^ a b c Browne 2001, p. 316.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 14.

- ^ a b Gaye 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 5.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 13: "If it wasn't for Mother, who was always there to console me and praise me for my singing, I think I would have been one of those child suicide cases you read about in the papers".

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 12: "From the time he was seven until he became a teenager, Marvin's life at home consisted of a series of brutal whippings".

- ^ Fleishman, Sandra (May 13, 2000). "Reading, 'Riting And Redevelopment". The Washington Post. p. G1.

- ^ Bonner, Alice (October 1, 1973). "The Golden Years: City's Randall Junior High School Celebrates 50th Anniversary". The Washington Post. p. C1

- ^ Harrington, Richard (April 2, 1984). "The Fallen Prince: Marvin Gaye & His Songs Full of Soul". The Washington Post. pp. B1, B8.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 23.

- ^ Gaye 2003, p. 197.

- ^ a b MacKenzie 2009, p. 153.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 24.

- ^ a b Hopkinson, Natalie (May 19, 2003). "House of Blues: Marvin Gaye's Boyhood Home Awaits the Wrecking Ball or a Second Act". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ Evelyn, Dickson & Ackerman 2008, pp. 290–291.

- ^ a b Simmons, Deborah (April 29, 2012). "Memories of Marvin Gaye kept alive by a loving sister". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "NCHA Lets Contract for New Project". The Washington Post. November 14, 1956. p. B2.

- ^ Gulla 2008, p. 333.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 34.

- ^ Redfern 2007, p. 228.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 36.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye No Military Hit". September 13, 2005. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Marv Goldberg's R&B Notebooks – MARQUEES". Archived from the original on April 8, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, p. 38.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, p. 39.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 40.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 47.

- ^ "Etta James". Ace Records. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Edmonds 2001a, p. 24.

- ^ Jet 1985b, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Bowman 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Des Barres 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Posner 2002, p. 116.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 88.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 26 – The Soul Reformation: Phase two, the Motown story. [Part 5]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ "Tribute To Nat By Marvin Gaye" (PDF). Record World: 19. March 20, 1965.

- ^ a b Gaye 2003, p. 65.

- ^ 1968 WS Gm4: Marvin Gaye performs national anthem. Major League Baseball. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ Kempton 2005, p. 207.

- ^ Posner 2002, p. 225.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 126.

- ^ Gulla 2008, p. 344.

- ^ Jet 1970, p. 60.

- ^ Jason Plautz (June 30, 2011). "Marvin Gaye, Detroit Lions Wide Receiver?". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ Music Urban Legends Revealed #16 Archived July 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Legendsrevealed.com (July 29, 2009). Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ Gates 2004, p. 332.

- ^ Lynskey 2011, pp. 155.

- ^ a b c d Bowman 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Vincent 1996, p. 129.

- ^ Whitburn 2004, p. 250.

- ^ a b Lynskey 2011, p. 157.

- ^ John Bush. What's Going On remains one of the few examples in modern music of critical acclaim and immediate commercial success occurring simultaneously. What's Going On was the first in a series of Motown albums in which albums overtook singles in commercial importance as well as cultural significance.review of What's Going On, by Marvin Gaye, allmusic.com (accessed June 10, 2005)

- ^ Jet 1973, p. 60.

- ^ MacKenzie 2009, p. 156.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye's lost 1972 album You're the Man to receive official release". February 7, 2019. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Jason Ankeny, review of Let's Get It On, by Marvin Gaye, allmusic.com (accessed June 10, 2005).

- ^ Edmonds 2001b, pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Ross, Diana/Marvin Gaye – Diana & Marvin." Encyclopedia of Popular Music, 4th ed. Ed. Colin Larkin. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Edmonds 2001b, p. 14.

- ^ "Let's Get It On – Marvin Gaye". SuperSeventies.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- ^ Jet 1975, p. 19.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 208.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye's Deliberate Start Builds to a Climactic Bacchanal". The New York Times. September 18, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye Here, My Dear". snopes.com. September 16, 1994. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 265.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, p. 267.

- ^ Gates 2004, p. 333.

- ^ Ritz 1991, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Ritz 1991, pp. 270–275.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 279.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 280.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 281.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 282.

- ^ Gaye 2003, p. 320.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 283.

- ^ Connolly, Kevin; Crook, Richard & Boelpaep, Bruno (March 30, 2024). "Marvin Gaye: Never-before heard music resurfaces in Belgium". BBC News. London. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 284.

- ^ Jet 1982, p. 59.

- ^ "What's on in Ostend". Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ^ Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (1st ed.). London: Reed International Books Ltd. p. 373. CN 5585.

- ^ Ebony 1985, p. 102.

- ^ Ivey, Justin (June 11, 2020). "Masta Killa Discusses Being Marvin Gaye's Cousin, Loss Of Popa Wu & RZA's Verzuz Battle". HipHopDX. Retrieved September 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c Ritz 1991, p. 333.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 334.

- ^ Ritz 1991, pp. 335–336.

- ^ "Jet". Johnson Publishing Company. April 23, 1984. Retrieved January 16, 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Around the Nation – No-Contest Plea in Death of Marvin Gaye". The New York Times. September 21, 1984. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye's father and killer dies". BBC. October 25, 1998. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Chris (October 1, 2012). "'The Man Was a Genius': Tales From Making Marvin Gaye's Final Album". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ a b "Marvin Gaye Biography". The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Bowman 2006, p. 5; Ritz 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Bowman 2006, p. 14; Ritz 1991, p. 100.

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 82.

- ^ Bowman 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b Bowman 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Bowman 2006, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Bowman 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Lynskey 2011, p. 156.

- ^ Vincet, Rickey (2013). Party Music : The Inside Story of the Black Panthers' Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music. Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 288–289.

- ^ a b Charnock, Ruth (2015). "'Things ain't what they used to be': Marvin Gaye and the making of What's Going On" (PDF). United Academics Journal of Social Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2015.

- ^ "Allmusic (Marvin Gaye – Overview)". Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ^ Roffman, Michael (February 8, 2019). "Marvin Gaye's lost 1972 album You're the Man to receive official release". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ Dyson 2004, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Marvin Gaye Is Shot And Killed; Pop Singer's Father Faces Charge". The New York Times. April 1, 1984. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Edmonds 2001a, p. 12.

- ^ a b Ritz 1991, p. ix.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye". Classic Bands. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Edmonds 2001a, p. 10.

- ^ Gilmore 1998, p. 220.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye – What's Going On". SuperSeventies.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ Jet 1985a, p. 56.

- ^ "Home Page". Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Jet 1987, p. 57.

- ^ Brooks-Bertram 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Jet 1990a, p. 17.

- ^ Jet 1990b, pp. 37.

- ^ "Experience the Music: One-Hit Wonders and the Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll". The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ "Rolling Stone: The Immortals, The first 50". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Rolling Stone: 100 Greatest Singers Of All Time". Rolling Stone. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Q Magazine Lists." Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "NME Writers Top 100 Albums of All Time". NME. November 30, 1985. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "The National Recording Registry 2003: National Recording Preservation Board (Library of Congress)". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye". Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016.

- ^ "Washington Parks and People: Marvin Gaye Park". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ ""Marvin Gaye Way" Coming to Deanwood – Housing Complex". April 1, 2009. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ "R&B Music Hall of Fame sets big weekend to induct sophomore class featuring Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Marvin Gaye, Norm N. Nite and more". The Plain Dealer. August 19, 2014. Archived from the original on September 10, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ "George Harrison, Madonna among those nominated for Songwriters Hall of Fame". Toronto Star. October 5, 2015. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame 2016 Nominees For Induction Announced". Songwriters Hall of Fame. October 5, 2015. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame to Induct Tom Petty, Marvin Gaye, Elvis Costello". Billboard. March 2, 2016. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame to Honor Marvin Gaye, Elvis Costello and Tom Petty". The New York Times. March 2, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Costello, Gaye, Petty Inducted into Songwriters Hall of Fame". ABC News. June 10, 2016. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "Bill to Name Post Office for Marvin Gaye Signed Into Law". L.A. Watts Times. July 26, 2018. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye's 'National Anthem'". NPR.org. NPR. February 7, 2003. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Bohdanowicz, Janet; Clamp, Liz (1994). Fashion Marketing. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-41505-939-8. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Robinson, Mark (March 1, 2001). The Sunday Times 100 Greatest TV Ads. HarperCollins. pp. 119–121. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Kristina Tunzi (March 15, 2008). "Buddy Miles, 60". Billboard. p. 60. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Billboard 1994, p. 70.

- ^ Billboard 1994, p. 80.

- ^ Ian Inglis (2003). Popular Music and Film. Wallflower Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-90336-471-0. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ María del Mar Azcona (July 11, 2011). The Multi-Protagonist Film. John Wiley & Sons. p. 168. ISBN 9781444351903. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Andrew Ford (2011). The Sound of Pictures. Schwartz Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-45876-294-8. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "Elvis, Marvin Gaye shake money makers in afterlife". CNN. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Blurred Lines jury awards Marvin Gaye family $7m". BBC News. March 11, 2015. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (January 12, 2016). "My Favorite Things, Part II". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Stutz, Colin (August 23, 2018). "Jeremy Geffen, Artist Manager & Creative Rights Group Founder, Dies at 40". Billboard. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Harris, Chris (February 6, 2006). "'Sexual Healing' Biopic Focuses on Marvin Gaye's Last Days". MTV News. Archived from the original on May 6, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye Biopic Moving Forward". Billboard. February 6, 2006. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Jessie L. Martin To Portray Marvin Gaye in Film Biopic". Jet. February 27, 2006. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Hernandez, Ernio (February 1, 2008). "Gandolfini Joins Martin for Marvin Gaye Film "Sexual Healing"". Playbill. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "James Gandolfini joins Marvin Gaye biopic". Entertainment Weekly. February 3, 2008. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Child, Ben (February 14, 2011). "Julien Temple to direct Marvin Gaye biopic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (November 26, 2012). "Lenny Kravitz To Play Marvin Gaye in Julien Temple Film". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ McNary, Dave (April 26, 2013). "Focus Adds Marvin Gaye Project To Cannes Slate". Variety. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (April 26, 2013). "Cannes: Focus Picks Up Marvin Gaye Biopic". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye Biopic, 'Sexual Healing' Teaser Clip Surfaces Online (VIDEO)". HuffPost. September 18, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Haglund, David (September 19, 2013). "Will the Marvin Gaye Movie Be Any Good?". Slate. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Sacks, Ethan (September 19, 2013). "'Sexual Healing' teaser trailer released: Jesse L. Martin channels legendary R&B singer Marvin Gaye for biopic". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Mcnab, Geoffrey (June 13, 2013). "Temple's Marvin Gaye film stalls". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ Sacks, Ethan (September 19, 2013). "'Sexual Healing' teaser trailer released: Jesse L. Martin channels legendary R&B singer Marvin Gaye for biopic". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (June 5, 2008). "F. Gary Gray to direct 'Marvin' movie". Variety. Archived from the original on August 26, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Campbell, Christopher (June 8, 2008). "F. Gary Gray Helming Other Marvin Gaye Biopic". Moviefone. Retrieved August 16, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Chagollan, Steve (April 1, 2010). "Music biopics struggle to make it to bigscreen". Variety. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Adler, Tim (May 16, 2010). "CANNES: Terrence Howard In Talks To Play Cameron Crowe's Marvin Gaye". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye: Mixed messages heard on the grapevine". April 5, 2011. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Singer, Matt (August 26, 2011). "Fall Preview: Cameron Crowe Talks "We Bought a Zoo", Buying Into Matt Damon and Why Animals Make Great Characters". Ifc.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Suskind, Alex (November 22, 2011). "Cameron Crowe Once Fired Ashton Kutcher; Was Planning Marvin Gaye Biopic With Will Smith". Moviefone. Retrieved August 16, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Lenny Kravitz Drops Out of Marvin Gaye Biopic". Rolling Stone. March 5, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ "Marvin Gaye Biopic 'Sexual Healing' Has Singer's Ex-Wife, Janis Gaye, 'Disappointed'". HuffPost. March 11, 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Platon, Adelle (July 14, 2016). "Marvin Gaye's Family on Board for 'What's Going On?' Documentary". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (July 12, 2016). "New Marvin Gaye Doc Features Unseen Footage". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Sun, Rebecca (November 30, 2016). "Jamie Foxx Producing Limited Series About Marvin Gaye (Exclusive) – Hollywood Reporter". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ Nevins, Jake (June 18, 2018). "Dr Dre to make Marvin Gaye biopic with rights to singer's catalogue". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (June 17, 2021). "Warner Bros. Lands Allen Hughes-Directed Marvin Gaye Film, Dr. Dre & Jimmy Iovine to Produce". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Veteran in America by William A. Pencak Page 167, Film and Veterans Archived October 29, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ TV Guide Chrome And Hot Leather Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cool Ass Cinema Tuesday, February 17, 2009 Chrome & Hot Leather (1971) review Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Divided Soul: The Life Of Marvin Gaye: The Life of Marvin Gaye by David Ritz Chapter 17 Hollywood Hustles Archived October 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Marvin Gaye – Live in Montreux 1980: Marvin Gaye: Movies & TV". Amazon. May 20, 2003. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Banks, James G.; Banks, Peter S. (2004). The Unintended Consequences: Family and Community, the Victims of Isolated Poverty. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America. ISBN 9780761828563.

- Batchelor, Bob (2005). Basketball in America: From the Playgrounds to Jordan's Game and Beyond. Haworth Press. ISBN 0-7890-1613-3.

- Berry, William Earl (February 1, 1973). "Marvin Gaye: Inner City Musical Poet". Jet.

- Bowman, Rob (April 2006). Marvin Gaye: The Real Thing (Media notes).

- Brooks-Bertram, Peggy (2009). Uncrowned Queens: African American Women Community Builders of Western New York, Volume 2 (Google eBook). SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-97229-771-4.

- Browne, Ray B. (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- Collier, Aldore (April 16, 1984). "Marvin Gaye: His Tragic Death and Troubled Life". Jet.

- Collier, Aldore (June 25, 1984). "Marvin Gaye's White Live-In Mate Suffers Miscarriage". Jet.

- Collier, Aldore (April 8, 1985). "A Year Later: What Happened to Marvin Gaye's Family, Fortune?". Jet.

- Collier, Aldore (May 6, 1985). "Book Reveals Marvin Gaye Feared He Would Turn Gay". Jet.

- Collier, Aldore (May 25, 1987). "Marvin Gaye's Mother Dies on Eve of Opening Drug Center She Founded As His Memorial". Jet.

- Collier, Aldore (October 15, 1990). "Gala Celebration Marks Marvin Gaye's Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". Jet.

- Collier, Aldore (April 23, 1990). "Murphy Requests Walk of Fame Star For Marvin Gaye". Jet.

- Davis, Sharon (1991). Marvin Gaye: I Heard It Through The Grapevine. Croydon, Surrey: Book marque Ltd. ISBN 1-84018-320-9.

- Des Barres, Pamela (1996). Rock Bottom: Dark Moments in Music Babylon. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-14853-4.

- Dyson, Eric Michael (2004). Mercy Mercy Me: The Art, Loves and Demons of Marvin Gaye. New York/Philadelphia: Basic Civitas. ISBN 0-465-01769-X.[permanent dead link]

- Edmonds, Ben (2001a). What's Going On?: Marvin Gaye and the Last Days of the Motown Sound. Canongate U.S. ISBN 1-84195-314-8.

- Edmonds, Ben (2001b). Let's Get It On (Deluxe ed.). Motown Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. MOTD 4757.

- Evelyn, Douglas; Dickson, Paul; Ackerman, S.J. (2008). On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. Sterling, Va.: Capital Books. ISBN 9781933102702.

- Gambaccini, Paul (1987). The Top 100 Rock 'n' Roll Albums of All Time. New York: Harmony Books.

- Garofalo, Reebee (1997). Rockin' Out: Popular Music in the USA. Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-13703-2.

- Gates, Henry Louis (2004). African American Lives. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19516-024-6.

- Gaye, Frankie (2003). Marvin Gaye, My Brother. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-742-0.

- Gilmore, Mikal (1998). Night beat: a shadow history of rock & roll. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-38548-435-0.

- Gulla, Bob (2008). Icons of R&B and Soul: An Encyclopedia of the Artists Who Revolutionized Rhythm. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34044-4.

- Gutheim, Frederick A.; Lee, Antoinette J. (2006). Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., From L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801883286.

- Heron, W. Kim (April 8, 1984). Marvin Gaye: A Life Marked by Complexity. Detroit Free Press.

- "Thousands Attend Last Rites For Tammi Terrell". Jet. April 9, 1970.

- Company, Johnson Publishing (November 13, 1975). "For Reading: Marvin Gaye receives special plaque from Ms. Shirley Temple Black". Jet.

{{cite magazine}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - Company, Johnson Publishing (March 29, 1982). "Landing Marvin Gaye Was a Task For CBS Records". Jet.

{{cite magazine}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - Jones, Regina (March 2002). "Unbreakable: Michael Jackson". Vibe.[permanent dead link]

- Kempton, Arthur (2005). Boogaloo: The Quintessence of American Popular Music. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-47203-087-3.

- Lynskey, Dorian (April 5, 2011). 33 Revolutions per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, from Billie Holiday to Green Day. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06167-015-2.

- MacKenzie, Alex (2009). The Life and Times of the Motown Stars. Right Recordings. ISBN 978-1-84226-014-2.

- Marx, Eve (September 18, 2009). 101 Things You Didn't Know About Sex (Google eBook). Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-44050-428-0.[permanent dead link]

- Otfinoski, Steven (2010). African Americans in the Performing Arts. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-43812-855-9.

- Posner, Gerald (2002). Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50062-6.

- Redfern, Nick (February 20, 2007). Celebrity Secrets: Official Government Files on the Rich and Famous. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-41652-866-1.

- Ritz, David (1991). Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81191-X.

- Ritz, David (July 1985). "The Last Days of Marvin Gaye". Ebony.

- Simmonds, Jeremy (2008). The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars: Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-754-8.

- Turner, Steve (1998). Trouble Man: The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 0-7181-4112-1.

- Vincent, Rickey (1996). Funk: The Music, the People, and the Rhythm of the One. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-13499-1.

- Ward, Ed, Geoffrey Stokes and Ken Tucker (1986). Rock of Ages: The Rolling Stone History of Rock and Roll. Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 0-671-54438-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weinger, Harry (November 5, 1994). "Jobete: Publishing Is The Highly Polished Jewel In The Gordy Co.'s Crown". Billboard.

- Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits: Complete Chart Information About America's Most Popular Songs and Artists, 1955–2003. Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7499-4.

- White, Adam (1985). The Motown Story. London: Orbis. ISBN 0-85613-626-3.

External links

[edit]- ‹The template AllMovie name is being considered for deletion.› Marvin Gaye at AllMovie

- Marvin Gaye at AllMusic

- Marvin Gaye at the Internet Broadway Database

- Marvin Gaye at IMDb

- Marvin Gaye interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- Marvin Gaye Biography

- FBI Records: The Vault - Marvin Gaye at vault.fbi.gov

- Additional archives

- Marvin Gaye

- 1939 births

- 1984 deaths

- 20th-century African-American male singers

- 20th-century American composers

- 20th-century American drummers

- 20th-century American keyboardists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American drummers

- African-American film score composers

- African-American male singer-songwriters

- African-American male pianists

- African-American pianists

- African-American United States Air Force personnel

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American expatriates in Belgium

- American expatriates in England

- American film score composers

- American funk drummers

- American funk keyboardists

- American funk singers

- American male drummers

- American male film score composers

- American male organists

- American manslaughter victims

- American multi-instrumentalists

- American Pentecostals

- American rhythm and blues keyboardists

- American rhythm and blues singer-songwriters

- American soul keyboardists

- American soul singers

- American rhythm and blues singers

- American male pop singers

- American tenors

- Columbia Records artists

- Deaths by firearm in California

- Gaye family

- Gordy family

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Military personnel from Washington, D.C.

- Motown artists

- Musicians from Detroit

- Musicians from Los Angeles County, California

- Northern soul musicians

- People from Topanga, California

- People from Southwest (Washington, D.C.)

- Progressive soul musicians

- Psychedelic soul musicians

- Record producers from California

- Rhythm and blues drummers

- Singer-songwriters from California

- Singer-songwriters from Michigan

- Singer-songwriters from Washington, D.C.

- Singers from Detroit

- Singers with a four-octave vocal range

- Soul drummers

- The Funk Brothers members