Saint Thomas Christian denominations

This article is missing information about Ecumenical relations. (December 2024) |

The Saint Thomas Christian denominations are Christian denominations from Kerala, India, which traditionally trace their ultimate origins to the evangelistic activity of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century.[1][2][3][4] They are also known as "Nasranis" as well. The Syriac term "Nasrani" is still used by St. Thomas Christians in Kerala. It is part of the Eastern Christianity institution.

Historically, this community formed a part of the Church of the East, served by metropolitan bishops and a local archdeacon.[5][6][7] By the 15th century, the Church of the East had declined drastically,[8][9] and the 16th century witnessed the Portuguese colonial overtures to bring St Thomas Christians into the Latin Catholic Church, administered by their Padroado, leading to the first of several rifts (schisms) in the community.[10][11][12] The attempts of the Portuguese culminated in the Synod of Diamper in 1599 and was resisted by local Christians through the Coonan Cross Oath protest in 1653. This led to the permanent schism among the Thomas' Christians of India, leading to the formation of Puthenkūr (New allegiance, pronounced Pùttènkūṟ) and Pazhayakūr (Old allegiance, pronounced Paḻayakūṟ) factions.[13] The Pazhayakūr comprise the present day Syro-Malabar Church and Chaldean Syrian Church which continue to employ the original East Syriac Rite liturgy.[5][14][15][16] The Puthenkūr group, who resisted the Portuguese, organized themselves as the independent Malankara Church,[17] entered into a new communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, and they inherited the West Syriac Rite from the Syriac Orthodox Church, which employs the Liturgy of Saint James, an ancient rite of the Church of Antioch, replacing the old East Syriac Rite liturgy.[18][5][19]

The Eastern Catholic faction is in full communion with the Holy See in Rome. This includes the aforementioned Syro-Malabar Church as well as the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, the latter arising from an Oriental Orthodox faction that entered into communion with Rome in 1930 under Bishop Geevarghese Ivanios (d. 1953). As such the Malankara Catholic Church employs the West Syriac liturgy of the Syriac Orthodox Church,[20] while the Syro-Malabar Church employs the East Syriac liturgy of the historic Church of the East.[5]

The Oriental Orthodox faction includes the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, resulting from a split within the Malankara Church in 1912 over whether the church should be autocephalous or rather under the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch.[21] As such, the Malankara Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Oriental Orthodox Church independent of the Patriarch of Antioch,[21] whereas the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church is an integral part of the Syriac Orthodox Church and is headed by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch.[18]

The Iraq-based Assyrian Church of the East's archdiocese includes the Chaldean Syrian Church based in Thrissur.[22] They were a minority faction within the Syro-Malabar Church, which split off and joined with the Church of the East Bishop during the 1870s. The Assyrian Church is one of the descendant churches of the Church of the East.[23] Thus it forms the continuation of the traditional church of Saint Thomas Christians in India.[24]

Oriental Protestant denominations include the Mar Thoma Syrian Church and the St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India.[25] The Marthoma Syrian Church were a part of the Malankara Church that went through a reformation movement under Abraham Malpan due to influence of British Anglican missionaries in the 1800s. The Mar Thoma Church employs a reformed variant of the liturgical West Syriac Rite.[26][27] The St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India is an evangelical faction that split off from the Marthoma Church in 1961.[28]

CSI Syrian Christians are a minority faction of Malankara Syrian Christians, who joined the Anglican Church in 1836, and eventually became part of the Church of South India in 1947, after Indian independence. The C.S.I. is in full communion with the Mar Thoma Syrian Church.[29][30][31][32] By the 20th century, various Syrian Christians joined Pentecostal and other evangelical denominations like the Kerala Brethren, Indian Pentecostal Church of God, Assemblies of God, among others. They are known as Pentecostal Saint Thomas Christians.[33][34]

Churches within Saint Thomas Christian tradition

[edit]

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Eastern Catholic

- Oriental Orthodox

- Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite, claim autocephality )

- Jacobite Syrian Christian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite, autonomous, under the Syriac Orthodox Church)

- Malabar Independent Syrian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite), independent, officially not part of Oriental Orthodox Communion)

- Oriental Protestant

- Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite – Oriental Protestant, independent)

- St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India (Syro-Antiochene Rite – Oriental Evangelical, independent)

- Apart from the above churches which claim Thomas as their founder, Nasranis can also be found in Protestant churches. They are,

- Saint Thomas Anglicans of the Church of South India (United Protestant denomination that holds membership in the Anglican Communion, World Methodist Council and World Communion of Reformed Churches)

- Pentecostal Saint Thomas Christians (Charismatic),[35][36][37][38] groups tracing their history back to the Malankara Church include the Kerala Brethren, Church of God (Kerala State),[39] and Indian Pentecostal Church of God.[40]

Their traditions go back to first-century Christian thought, and the seven "and a half" churches established by Thomas the Apostle during his mission in Malabar.[41][42][43] These are located at Kodungalloor (Muziris), Paravur, Palayoor, Kokkamangalam, Niranam, Nilackal, Kollam, and the Thiruvithamcode Arappally in Kanyakumari district.

Nasrani people

[edit]

The Nasranis are an ethnic people, and a single community.[44] As a community with common cultural heritage and cultural tradition, they refer to themselves as Nasranis.[44] However, as a religious group, they refer to themselves as Mar Thoma Khristianis or in English as Saint Thomas Christians, based on their religious tradition of Syriac Christianity.[44][45][46]

However, from a religious angle, the Saint Thomas Christians of today belong to various denominations as a result of a series of developments including Portuguese persecution[47] (a landmark split leading to a public Oath known as Coonen Cross Oath), reformative activities during the time of the British (6,000 - 12,000 Jacobites joined the C.M.S. in 1836, after the Synod of Mavelikara; who are now within the Church of South India), doctrines and missionary zeal influence ( Malankara Church and Patriarch/Catholicos issue (division of Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and Malankara Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church (1912)).

St. Thomas Christian families who claim their descent from ancestors who were baptized by Apostle Thomas are found all over Kerala.[48][49] St. Thomas Christians were classified into the social status system according to their professions with special privileges for trade granted by the benevolent kings who ruled the area. After the 8th century when Hindu Kingdoms came to sway, Christians were expected to strictly abide by stringent rules pertaining to caste and religion. This became a matter of survival. This is why St. Thomas Christians had such a strong sense of caste and tradition, being the oldest order of Christianity in India. The Archdeacon was the head of the Church, and Palliyogams (Parish Councils) were in charge of temporal affairs. They had a liturgy-centered life with days of fasting and abstinence. Their devotion to the Mar Thoma tradition was absolute. Their churches were modelled after Jewish synagogues.[49] "The church is neat and they keep it sweetly. There are mats but no seats. Instead of images, they have some useful writing from the holy book."[50][51]

In short, the St. Thomas Christians of Kerala have blended well with the ecclesiastical world of the Eastern Churches and with the changing socio-cultural environment of their homeland.[49] Thus, the Malabar Church was Hindu or Indian in culture, Christian in religion, and Judeo-Syriac-Oriental in terms of origin and worship.[49]

Apostolic origin

[edit]According to the 1st century annals of Pliny the Elder and the author of Periplus of the Erythraean sea, Muziris in Kerala could be reached in 40 days' time from the Egyptian coast purely depending on the southwest monsoon winds.[52] The Sangam works Puranaooru and Akananooru have many lines which speak of the Roman vessels and the Roman gold that used to come to the Kerala ports of the great Chera kings in search of pepper and other spices, which had enormous demand in the West.[53]

The lure of spices attracted traders from the Middle East and Europe to the many trading ports of Keralaputera (Kerala) — Tyndis, (Ponnani), Muziris, near Kodungallur, Niranam, Bacare, Belitha, and Comari (Kanyakumari) long before the time of Christ.[53][54] Thomas the Apostle in one of these ships, arrived at Muziris in 52, from E’zion-ge’ber on the Red Sea.[55] He started his gospel mission among the Jews at "Maliyankara" on the sea coast.[56]

Jews were living in Kerala from the time of Solomon.[3][57] Later, large numbers of them arrived in 586 BC and 72 AD. Malabari Jewish tradition hold these facts.[citation needed]

Its traditionally believed that during his stay in Kerala, the Apostle baptized the Jews and some of the wise men[citation needed] who adored the Infant Jesus.[58] The Apostle established seven "and a half" churches in Malabar at Kodungalloor (Muziris), Paravur, Palayoor, Kokkamangalam, Niranam, Nilackal, Kollam, and the Thiruvithamcode Arappally in Kanyakumari district.[59]

The Apostle also preached in other parts of India. The visit of the Apostle Thomas to these places and to Mylapore on the East coast of India can be read in the Ramban Songs of Thomas Ramban, set into 'moc', 1500.[59] He was martyred in 72 at Little Mount, a little distant from St. Thomas Mount, and was buried at San Thome, near the modern city of Chennai.[59] The body of Apostle Thomas was translated to Edessa, Iraq. It is now in Ortona, Italy. Relics of Apostle Thomas were translated to the San Thome Cathedral in Chennai and to St Thomas Church in Palayur, near Guruvayoor at Chavakkad Taluk, Thrissur District in Kerala.[60]

Several ancient writers mention India as the scene of St. Thomas’ labours. Ephrem the Syrian (300–378) writes in the forty-second of his "Carmina Nisibina" that the Apostle was put to death in India, and that his remains were subsequently buried in Edessa, brought there by a merchant.[1] St. Ephraem in a hymn about the relics of St. Thomas at Edessa depicts Satan exclaiming, "The Apostle whom I killed in India comes to meet me in Edessa." Gregory Nazianzen, (329–389), in a homily says; "What! were not the Apostles foreigners? Granting that Judea was the country of Peter, what had Saul to do with the Gentiles, Luke with Achaia, Andrew with Epirus, Thomas with India, Mark with Italy?." Ambrose (340–397) writes "When the Lord Jesus said to the Apostles, go and teach all nations, even the kingdoms that had been shut off by the barbaric mountains lay open to them as India to Thomas, as Persia to Mathew."

There are other passages in ancient liturgies and martyrologies which refer to the work of St. Thomas in India. These passages indicate that the tradition that St. Thomas died in India was widespread among the early churches.[61]

Many writers have mentioned that the Apostle established seven "and a half" churches in Malabar.[62][2] They are:[63]

- Maliankara - Kodungalloor

- Kottakkavu Paravur

- Niranam

- Palayoor

- Nilackal

- Kokkamangalam

- Kollam

- Thiruvithancode - This church made on land donated by the local king or arajan (arappally/arachapally in Malayalam)

Doctrine of the Apostles states that, "India and all its countries...received the Apostle's hand of priesthood from Judas Thomas…." From 345 AD, when Knanaya Christians arrived from Persia, they had continued the relationship with their home Church in Persia, which was also established by St. Thomas the Apostle.

Rough chronology

[edit]

Following is a rough chronology of events associated with St. Thomas Christianity.[64][65]

1st century

[edit]- 30 Crucifixion of Jesus.

- 40 Apostle Thomas in the service of King Gondophares in Takshasila in Pakistan.

- 52 Apostle Thomas, landed at Muziris near Paravur, an ancient port city of Malabar (Present-day Kerala).

- 52–72 The Apostle founded eight churches: Palayoor, Kodungaloor, Paravur, Kothamangalam, Niranam, Nilackal, Kollam and Thiruvithamcode 'half church'. [Other claimants for half church status are Malayattoor and Athirappalli]. Six of the churches are preserved even now (see pictures). The church at Kollam is believed to have been submerged in the ocean, possibly following tidal waves, while the actual location of the church at Chayal has not been identified conclusively.[citation needed].

- 64 Formation of the Metropolitanate of India.

- 72 Apostle Thomas attained martyrdom at St. Thomas Mount in Chennai and is buried on the site of San Thome Cathedral.[66]

2nd century

[edit]- 105 Kuravilangad Church was believed to be founded, after the first ever Marian Apparition occurred there

- 190 Pantaenus, the founder of the famous Catechetical School of Alexandria, visited India[67] and the Nasranis. He found that the local people were using the Gospel according to Matthew in Hebrew language. He took this Hebrew text back to his library at the School in Alexandria.[68]

4th century

[edit]- 325 Archbishop John, of Persia and Great India, at the first Ecumenical Council of Nicea.

- 325 Kadampanad Church (St.Thomas Orthodox Syrian Cathedral) built by settlers from Chayal (Nilackel)

- 345 Thomas of Cana (Knai Thoma) and his party arrive to Kerala and solidify the East Syriac tradition. Thoma receives a copper plate grants known today as the Thomas of Cana copper plates which gave the St. Thomas Christians socioeconomic privileges in the Chera Dynasty.

5th century

[edit]- 400 St. John Nepumsian's Forane Church, Parappukkara is built, originally devoted to Mother Mary.

- 427 Champakulam Church was consecrated.

6th century

[edit]- 510 Udayamperoor (Diamper) church built by Mar Thoma Nasranis (Saint Thomas Christians). The church is under the Syro-Malabar Catholic Archdiocese of Ernakulam-Angamaly

- 522 Cosmas Indicopleustes visited South India.

- 593 Edappally Church was built.

7th century

[edit]- Marthoma Christians constructed Kolenchey St. Peter's and St. Paul's Orthodox Church around 650 AD

8th century

[edit]- 717 Thumpamon St. Mary's Orthodox Syrian Church was founded.

- 722 Karingachira St. George's Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church was founded

- 774 Emperor Veera Raghava gives copperplate to Iravikorthan.

9th century

[edit]- 824 Beginning of Kollavarsham (Malayalam Era).First Tharissapalli sasanam (copper plate) by Stanu Ravi Gupta Perumaal to Nasranis.

- 824 from Persia. Sabor and Afroth at Quilon.[69]

- 849 Deed given by King Ayann Adikal Thiruvadikal of Venad, to Easow-data-veeran that grants 72 royal privileges of the Nasranis in which the Nasranis and Arabs signed in three languages Hebrew, Pahlavi and Kufic (An Arabic script).[70]

10th century

[edit]- 905 St. Mary's Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church in Pallikkara established.[71]

- 945 Thomas of Cana landed at Cranganore with 72 families.

- 999 Marth Mariam Syro-Malabar Catholic Forane Church, Arakuzha founded.

- 999 By the Thazhekad Sasanam written in Pali the language the canonical language of Buddhists, the Nasranies granted special rights and privileges.[72]

11th century

[edit]- 1100-1125 St.Thomas Christians built the Marthoman Malankara Orthodox Church at Mulanthuruthy.

- 1125 Kudamaloor St. Mary's Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, believed to be built by King of Chempakasserry.

13th century

[edit]- 1225 North Pudukkad church founded.

- 1293 Marco Polo, a Venetian traveler, visited the tomb of St. Thomas (at Mylapore).[citation needed]

14th century

[edit]- 1325 Enammavu church founded.

- 1339 Kallooppara Church (St Mary's Orthodox Church) was founded

- 1342 Pazhuvil Church founded

- 1375 Velayanadu Church founded

15th century

[edit]- 1490 Two Church of the East bishops John and Thomas in Kerala.

- 1494 June 7 Treaty of Tordesillas. Division of the world and mission lands between Spain and Portugal.

- 1498 May 20 Vasco de Gama lands at Kappad near Kozhikode.

- 1499 Cabral's fleet carried a vicar, eight secular priests, and eight Franciscans to Kozhikode,[73]

- 1499. In Calicut, the friars reputedly converted a Brahman and some leading Nayars.[74]

16th century

[edit]- 1502 November 7 Vasco de Gama's second visit to Cochin.

- 1503 Dominican Priests at Kochi.

- 1503 Mar Yabella, Denaha and Yakoob from Persia in Kerala.

- 1503 September 27 Work commenced on Cochin Fort and the Santa Cruz church.

- 1514 Portuguese Padroado begun.

- 1514 Jewish migration from Kodungalloor to Kochi.

- 1514 June 12 Portuguese Funchal rule over Christians in India.

- 1524 December 24 Vasco de Gama buried at St. Francis Church, Fort Cochin.

- 1534 November 3 Goa Catholic Diocese erected. The Parishes of Kannur, Cochin, Quilon, Colombo and Sao Tome (Madras) belonged to it.

- 1540 The Franciscan Fr.Vincent De Lagos starts the Cranganore Seminary.

- 1542 May 6 St. Francis Xavier, Apostolic Nuncio in the East, reaches Goa.

- 1544–45 St. Francis Xavier in Travancore.

- 1548 Dominican Monastery founded in Cochin.

- 1549 Mar Abuna Jacob, A Chaldean Bishop, stayed at St. Antonio Monastery, Cochin.

- 1550 First Jesuit House in Kochi.

- 1552 December 3 Death of St. Francis Xavier.

- 1555 Mattancherry Palace was built by Portuguese for the King of Cochin.

- 1557 Pope Paul IV erects the Diocese of Cochin. Canonization process of Francis Xavier begun at Cochin.

- 1565 Archdiocese of Angamaly erected.

- 1567 Jews constructed a temple at Mattancherry[75]

- 1567 Angamaly Cheriyapally was built.

- 1568 Synagogue of White Jews built in Cochin.

- 1570 Angamaly Kizhakkeppally was built.

- 1577 Vaippicotta Seminary of the Jesuits started.

- 1579 Augustinians reached Cochin.

- 1580 Kallissery St. Mary's Knanaya Jacobite Syrian Orthodox church established

- 1583 Synod at Angamaly by Bishop Abraham.

- 1597 Bishop Abraham, the last foreign Archbishop, died and was laid to rest at St. Hormis church, Angamaly.

- 1599 December 20 Francis Roz was declared bishop of Angamaly.

- 1599 June 20–26 Archbishop Alexis Menezes convenes the Synod of Diamper (Udayamperoor).

17th century

[edit]- 1600 August 4 Padroado-rule imposed on Nasranis.

- 1601 Francis Roz was appointed as the first Latin bishop of the St. Thomas Christians.

- 1609 December 3 Erection of the Diocese of Cranganore. The Archdiocese of Angamaly suppressed.

- 1610 December 22 The Metropolitan of Goa limits the Pastoral Jurisdiction of Nasranis to Malabar.

- 1624 Dominican Seminary at Kaduthuruthy.

- 1626 February 5 Edappally Ashram started for the Religious Community of St. Thomas Christians

- 1652 August 23 Mar Ahatallah in Madras, not allowed to enter Kerala.

- 1653 January 3 Coonan Cross Oath at Mattancherry, Cochin.

- 1653 May 22 Archdeacon Thomas Kathanar, ordained as Mar Thoma I at Alangad by the laying of hands by 12 priests. Beginning of schism among Saint Thomas Christians. 1653–1670 Mar Thoma I.

- 1657 Apostolic Commissary Joseph of St. Mary OCD (Sebastiani), a Carmelite, in Malabar.

- 1659 December 3 The Vicariate of Malabar is erected by Pope Alexander VII.

- 1659 December 24 Joseph Sebastini bishop and appointed the Vicar Apostolic of Malabar.

- 1663 January 6 The Dutch conquer Cochin and destroy Catholic churches and institutions in Cochin, except the cathedral and the church of St. Francis Assisi.

- 1663 January 31 Chandy Parambil ordained as bishop.

- 1665 Mar Gregorius Abdul Jaleel, believed to be from Antioch. Consecration of Marthoma I.

- 1670–1686 Mar Thoma II.Portuguese starts campaigning to bring Nasranis again under Catholicism.

- 1682 Seminary for Syrians at Verapoly.

- 1685 Eldho Mor Baselios of the Syriac Orthodox Church arrives at Kothamangalam from Persia.

- 1686 Hortus Malabaricus in 12 volumes printed in 17 years. Mathoma III ordained by Ivanios Hirudyathulla (from Antioch).

- 1686–1688 Mar Thoma III - third Malankara Metropolitan

- 1688–1728 Mar Thoma IV - fourth Malankara Metropolitan

18th century

[edit]- 1709 March 13 Vicariate of Malabar is suppressed and the Vicariate of Verapoly is erected by Pope Clement XI.

- 1718–1723 Ollur St. Anthony's Syro-Malabar Catholic Forane Church was established.

- 1728–1765 Mar Thoma V.

- 1765–1808 Mar Thoma VI (Dionysius I)

- 1772 First Malayalam book Sampskhepa Vedartham (Rome) by Clement Pianius.

- 1773 Pope Clement XIV suppresses the Jesuit Order, except in Russia and Prussia.

- 1782 December 16 Kariyattil Joseph elected Archbishop of Cranganore; Consecr. Lisbon 1783; died in Goa on the way back to Malabar, 9 September 1786.

- 1785 Varthamanappusthakam, the first written travelogue in India by Paremakkal Thoma Kathanar.

- 1795 October 20 Conquest of Cochin by the British.

19th century

[edit]- 1808–1809 Mar Thoma VII.

- 1809–1816 Mar Thoma VIII.

- 1816 Mar Thoma IX.

- 1815 March – The first educational institution in Kerala, Orthodox Theological Seminary, Kottayam opens at Kottayam with Abraham Malpan, (Syriac), Konattu Varghese Malpan (Syriac) and Kunjan Assan (Sanskrit) as teachers.[76]

- 1816 C.M.S missionaries in Kerala.

- 1816 for nine months the tenth Malankara Metropolitan Pulikkottil Joseph Dionysious I (Dionysious II).

- 1816–1817 Mar Philoxenos II, Kidangan, of Malabar Independent Syrian Church (Thozhiyoor Sabha) as Malankara Metropolitan.[77]

- 1817–1825 Mar 11th Malankara Metropolitan- Punnathra Dionysious (Dionysious III).

- 1825–1852 12th Malankara Metropolitan – Cheppad Philipose Dionysius (Dionysius IV).

- 1836 6,000 - 12,000 Jacobites joined Anglican C.M.S. Church (later merged with other similar Churches to form the Church of South India).

- 1838 April 24 Dioceses of Cochin and Crnaganore are annexed to the Vicariate of Verapoly.

- 1838 The Queen of Portugal suppressed all religious orders in Portugal and in her mission lands.

- 1840 April 10 Kerala Syrian Catholics came under the archdiocese of Verapoly.

- 1852–1877 13th Malankara Metropolitan - Mathews Athanasius Metropolitan.

- 1861 May 20 Bishop Rocos sent by the Patriarch of Chaldea reaches Kerala.

- 1864–1909. Pulikkottil Joseph Dionysious II (Dionysious V) 14th Malankara Metropolitan

- 1867 May 7 Property donated by Syrians to the King of Portugal to start a Seminary at Aluva. It was administered by the Diocese of Cochin.

- 1867 The Portuguese Missionaries start a seminary at Mangalapuzha for Syrian students.

- 1874 Bishop Elias Mellus sent by the Patriarch of Chaldea reaches Kerala – Mellus Schism.

- 1875 June-HH Patriarch of Antioch Peter III arrives in Kerala.

- 1876 June 28–30 HH Patriarch of Antioch Peter III convenes the Mulanthuruthy Synod. A section of Saint Thomas Christians came under his jurisdiction.

- 1877–1893 – Thomas Athanasius Metropolitan, Metropolitan of Reformist faction of Malankara Church (later Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church)

- 1886 The Archdiocese of Cranganore is suppressed.

- 1887 May 19 The St. Thomas Christians are totally segregated from the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Verapoly and from the Padroado.

- 1889 Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church separated from Malankara Church

- 1893–1910 – Titus I Thoma Metropolitan, Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church Metropolitan.

20th century

[edit]- 1909 Geevarghese Dionysius (Dionysius VI), the 15th Malankara Metropolitan, and Paulose Mor Koorilose Kochuparambil consecrated by the then incumbent Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, Ignatius Abded Aloho II.

- 1910 Mar Thoma XVI – Titus II Thoma Metropolitan, Marthoma Metropolitan (1910–1944)

- 1911 Dionysius VI excommunicated by Patriarch Ignatius Abded Aloho II.

- 1911 Paulose Mor Koorilose Kochuparambil. Malankara Metropolitan of the Malankara Syrian Orthodox Church (1911-1917)

- 1912 September 15 Baselios Paulose I, Malankara Orthodox Catholicos, enthroned by Patriarch Ignatius Abded Mshiho II, ousted Patriarch of Antioch established the Catholicate of the East in Malankara Church (at Niranam St. Mary's Church).[78]

- 1917 St. Paulose Mor Athanasius (Valiya Thirumeni), Malankara Metropolitan of the Malankara Syrian Orthodox Church (1917-1953).

- 1921 – The Malankara Full Gospel Church of God was founded.[79]

- 1923 December 21 Reinstated the Syro Malabar Church Hierarchy for Syrian Catholics with Ernakulam as the Metropolitan See, Archbishop Augustine Kandathil as the Metropolitan and Head of the Church, and Trichur, Changanacherry and Kottayam as sufragan Sees.

- 1925 Baselios Geevarghese I, Malankara (Indian) Orthodox Catholicos (1925-1928).

- 1927 March 19 Varghese Payyappilly Palakkappilly founded the Congregation of the Sisters of the Destitute.

- 1929 October 5 Death of Varghese Payyappilly Palakkappilly.

- 1929 Baselios Geevarghese II, Malankara (Indian) Orthodox Catholicos (1929–1934).

- 1930 September 20 Ivanios with Theophilus established communion with the Catholic Church. The Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.[80]

- 1931 Mor Elias III, the Patriarch of Antioch and all the East left Mosul on 6 February 1931 accompanied by Mor Clemis Yuhanon Abbachi, Rabban Quryaqos (later Mor Ostathios Quryaqos), and Rabban Yeshu` Samuel, his secretary Zkaryo Shakir and translator Elias Ghaduri. They set sail to India on 28 February 1931 from Basra.

- 1932 Ignatius Elias III, the Patriarch of Antioch and all the East was buried near St. Stephen's church Manjanikkara on Sunday 13 February

- 1932 June 11 The establishment of the Syro-Malankara Catholic Hierarchy by Pope Pius XI. Ivanios becomes Archbishop of Trivandrum, and Theophilus Bishop of Tiruvalla.

- 1934 Malankara Syrian Church accepts new constitution. and elected Baselios Geevarghese II as the 16th Malankara Metropolitan

- 1934–1964 Baselios Geevarghese II, 16th Malankara Metropolitan (1934–1964).

- 1935 – The Indian Pentecostal Church of God, which broke away from the Malankara Full Gospel Church of God, was registered.[40]

- 1944 – Abraham Mar Thoma Metropolitan, Marthoma Metropolitan (1944–1947).

- 1947 – Juhanon Mar Thoma Metropolitan, Marthoma Metropolitan (1947–1976).

- 1947 November 2 Bishop Gheevarghese Gregorios of Parumala declared first native Indian saint along with Catholicos Baselios Eldho.

- 1950 July 18 The Portuguese Padroado over the Diocese of Cochin (from 1557 February 4 until 1950 July 18) suppressed and the Diocese of Cochin handed over to native clergy.

- 1952 December 28–31 Jubilee Celebration of St. Thomas and St. Francis Xavier at Ernakulam.

- 1958 - Supreme Court verdict in Malankara Church dispute in favour of Catholicos faction (accepting the Constitution of 1934, establishment of Catholicate in Malankara and the election of Gheevarghese II as Malankara Metropolitan).

- Reunification between Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church (Patriarch faction) and Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Metropolitan faction)

- 1961 January 26 St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India was inaugurated (separated from the Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar)

- 1964 Baselios Augen I, Malankara Orthodox Catholicos of the East and 17th Malankara Metropolitan) (1964–1975).

- 1972 Fraction split in Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church as 'Jacobite fraction' (in favour of full submission to the Antiochian Patriarch) and 'Orthodox fraction' (in favour of autocephaly).

- 1972 December 27, the 19th Centenary of the Martydom of St. Thomas the Apostle is celebrated at Ernakulam under the auspices of Orthodox, Catholic, Jacobite, Marthoma and C.S.I. Churches.

- 1972 – The Church of God (formerly known as Malankara Full Gospel Church of God) split into the Nasrani dominated Church of God Kerala State and Dalit Christian Church of God Kerala Division[39]

- 1973 July 3 The Governor of Kerala and the Cardinal release the St. Thomas stamp and the T.En.II for sale.

- 1975 Baselios Mar Thoma Mathews I, Malankara (Indian) Orthodox Catholicos of the East and 18th Malankara Metropolitan) (1975–1991).

- 1975 Aboon Mor Baselios Paulose II, Malankara Syriac Orthodox (Jacobite) Catholicoi (1975–1996)

- 1976-1999 – Alexander Mar Thoma Metropolitan, Marthoma Metropolitan.

- 1986 1–10 February Visit of Pope John Paul II to India.

- 1986 8 February Chavara Kuriakose Elias and Sr. Alphonsa are proclaimed blessed by Pope John Paul II.

- 1991–2005 Baselios Mar Thoma Mathews II (Catholicos of the East and 19th Malankara Metropolitan).

- 1993 – The Believers Eastern Church was founded.

- 1995 - Supreme Court Verdict in Malankara Church dispute (2nd Samudaya(Community) Case)

- 1999–2007 – Philipose Chrysostom Mar Thoma Metropolitan, Marthoma Metropolitan.

21st century

[edit]- 2002 - Under the observation of the Supreme Court of India, the Malankara Syrian Christian Association meeting held on 20 March 2002 at Parumala Seminary elected Baselios Mar Thoma Mathews II as the Malankara Metropolitan. The Supreme Court of India has confirmed by its Order on 12 July 2002 that Baselios Mar Thoma Mathews II is the unquestionable Malankara Metropolitan of the Malankara Church.

- 2002 Jacobite faction dissociated the Malankara Association conducted by Supreme Court of India and appointed Aboon Mor Baselios Thomas I as Metropolitan Trustee of Jacobite Syrian Church and Catholicose under the Patriarch of Antioch.

- 2002 – The Kerala High Court declared the St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India and St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India Fellowship to be two distinct entities.[81]

- 2005-2010 - Baselios Mar Thoma Didymos I 20th Malankara Metropolitan and seventh Catholicos of Malankara

- 2005 February 10 Pope John Paul II elevated the Archdiocese of Trivandrum to a Major Archdiocese, elevating the Archbishop to Major Archbishop (called Catholicos by Syro-Malankara Catholics)

- 2007 February 10 Baselios Cleemis Catholicos (Malayalam: മോറന് മോര് ബസേലിയോസ് കര്ദിനാള് ക്ലിമ്മിസ് കാതോലിക്ക ബാവ) is elected as head of the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church by the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church Holy Synod in 2005.

- 2007 March 5 Baselios Cleemis enthroned as Major Archbishop-Catholicos, succeeding Baselios Cyril. Ecclesial communion was confirmed by Pope Benedict XVI.

- 2007 – Joseph Mar Thoma Metropolitan enthroned as Marthoma Metropolitan.

- 2007 December 25 Different fractions were merged in St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India(Church and Fellowship fraction)

- 2009 September 6 Varghese Payyappilly Palakkappilly declared Servant of God.

- 2010 November 1 Baselios Mar Thoma Paulose II enthroned as 21st Malankara Metropolitan and eighth Catholicos of Malankara.

- 2011 May 24 George Alencherry (Malayalam: ആലഞ്ചേരീല് മാര് ഗീവര്ഗിസ്) elected Major Archbishop of the Syro-Malabar Church.

- 2011 29 May George Alencherry enthroned as Major Archbishop.

- 2012 February 18 George Alencherry was created Cardinal of the Catholic Church.

- 2012 24 November Baselios Cleemis Catholicos created Cardinal of the Catholic Church.

- 2018 Elevation of Kuravilangad Church to 'Major Archiepiscopal Marth Mariam Archdeacon Pilgrim Church'

- 2020 Theodosius Mar Thoma XXII enthroned as Marthoma Metropolitan.

Early history

[edit]

Doctrine of the Apostles states that, "India and all its countries . . . received the Apostle's hand of priesthood from Judas Thomas…." From an early period the Church of St. Thomas Christians came into a lifelong relationship with the Church of the East[citation needed], which was also established by Thomas the apostle according to early Christian writings. The Primate or Metropolitan of Persia consecrated bishops for the Indian Church, which brought it indirectly under the control of Seleucia.[82][83]

The Church of the East traces its origins to the See of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, said to be founded by Thomas the Apostle. Other founding figures are Mari and Addai as evidenced in the Doctrine of Addai and the Holy Qurbana of Addai and Mari. This is the original Christian church in what was once Parthia: eastern Iraq and Iran. The See of Seleucia-Ctesiphon developing within the Persian Empire, at the east of the Christian world, rapidly took a different course from other Eastern Christians.

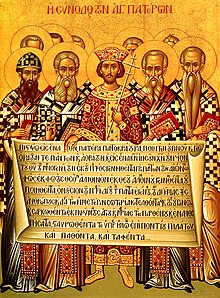

The First Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea in Bithynia (present-day İznik in Turkey), convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325, was the first Ecumenical council of the Christian Church, and most significantly resulted in the first uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed. It is documented that John, the Bishop of Great India attended the council. The prelate signs himself as "John the Persian presiding over the Churches in the whole of Persia and Great India."[84] Some centuries following, the Persian Church suffered severe persecutions. The persecuted Christians and even bishops, at least on two occasions, sought an asylum in Malabar.[85]

The Rock crosses of Kerala found at St.Thomas Mount and throughout Malabar coast has inscriptions in Pahlavi and Syriac. It is dated from before the 8th Century.[86]

In 825, the arrival of two bishops are documented, Sapor and Prodh.[87] Le Quien says that "these bishops were Chaldaeans and had come to Quilon soon after its foundation. They were men illustrious for their sanctity, and their memory was held sacred in the Malabar Church. They constructed many churches and, during their lifetime, the Christian religion flourished especially in the kingdom of Diamper."[87]

The beginning of Kolla Varsham resulted in the origin of Christianity in Kerala as an individual religion outside vedic Vaishnavism[citation needed]

The Church after Thomas

[edit]In 190, Pantaenus, probably the founder of the famous Catechetical School of Alexandria, visited India and the Nasranis.[67]

The First Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea in Bithynia (present-day İznik in Turkey), convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325, was the first Ecumenical council of the Christian Church, and most significantly resulted in the first uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed. Many historians have written that ‘’Mar John, the Bishop of Great India’’ attended the council.[citation needed]

Church life bore characteristics of a church which had its origin and growth outside the Graeco-Roman world. There was no centralized administrative structure on a monarchical pattern. The territorial administrative system which developed after the diocesan pattern within the eastern and western Roman empires did not exist in the Indian Church. "They have the uncorrupted Testament Which they believe was translated for them by St. Thomas the apostle himself."[88]

Theophilus (ca 354) as recorded by church historian Philostorgius mentions about a church, priests, liturgy, in the immediate vicinity of the Maldives, which can only apply to a Christian church and faithful on the adjacent coast of India. The people referred to were the Christians known as a body who had their liturgy in the Syriac language and inhabited the west coast of India, i.e., Malabar.[citation needed]

Shapur II the Great was the ninth King of the Sassanid Empire from 309 to 379. During that period, there was persecution against Christians. So in AD 345 under the leadership of Thomas of Cana 72 families landed at Muziris near Cranganore. They formed the group known as Knanaya Christians. They cooperated with the Malankara Church, attended worship services together but remained a separate identity They had regular visitors from their home land. Some of their priests and bishops visited them. But these visiting bishops had no authority over Saint Thomas Christians.[89][90]

The Church is mentioned by Cosmas Indicopleustes (about 535). He notes that, "There are Christians and believers in Taprobane (Sri Lanka), in Malabar where pepper grows there is a Christian church. At a place known as Kalyan, there is a bishop sent from Persia.".[91][92]

St. Gregory of Tours, before 590, reports that Theodore, a pilgrim who had gone to Gaul, told him that in that part of India where the corpus (bones) of St. Thomas had first rested, there stood a monastery and a church of striking dimensions and elaborately adorned, adding: "After a long interval of time these remains had been removed thence to the city of Edessa."[1]

See of St.Thomas the Apostle

[edit]As per the tradition of Saint Thomas Christians, St. Thomas the Apostle established his throne in India and India was his See (Kolla Hendo), therefore the see of the metropolitan of Saint Thomas Christians was India and used the title Metropolitan and Gate of all India.[93] In Syriac Manuscript Vatican Syriac Codex 22 the title given for the Metropolitan of the Saint Thomas Christians was "the superintendent and ruler of the holy see of St.Thomas the Apostle".

Early rituals and culture

[edit]The life-style of the Saint Thomas Christians might be stated as "Indian in culture, Christian in faith and Oriental in worship".[citation needed]

Social and culture

[edit]

Socially and culturally these Saint Thomas Christians remain as a part of the wider Indian community. They keep their Indian social customs, names and practices relating to birth, marriage, and death. They have Biblical names (Mar Thoma Christian names). At the same time they follow a number of Jewish customs like worship, baptism, wedding and other ceremonies which are entirely different from Western Churches.[citation needed]

Collection of deeds

[edit]The rulers of Kerala, always appreciated the contributions of St. Thomas Christians to the country and society. Thazhekad sasanam and deeds on copper plates bear witness to it. Five sheets of the three copper plates are now in the custody of St. Thomas Christians.[citation needed]

- Thazhekad sasanam is one of the earliest surviving edicts granting special privileges to the St. Thomas Christians. The edict dating back to about 340-360 AD was written on stone and provides proof of the early existence of St. Thomas Christians in Kerala.[citation needed]

- Iravi Corttan Deed: In the year 774 AD. Sri Vira Raghava Chakravarti, gave a deed to Iravi Corttan of Mahadevarpattanam.[citation needed]

- Tharissa palli Deed I: Perumal Sthanu Ravi Gupta (844-885) gave a deed in 849 AD, to Isodatta Virai for Tharissa Palli (church) at Curakkeni Kollam. According to historians, this is the first deed in Kerala that gives the exact date.[94]

- Tharissa palli Deed II: As Continuation of the above deed was given after 849 AD.[citation needed]

First 15 centuries

[edit]In 883 King Alfred the great of Wessex in England sent donations to the Christians in Malabar.[95][96] Marco Polo visited Malabar on his return journey from China. He wrote about the people whom he saw in Malabar, this way. "The people are idolaters, though there are some Christians and Jews among them. They speak a language of their own. The king is tributary to none."[97][98]

Persian Rock crosses

[edit]The two Rock crosses of Kerala are found at Kottayam, one each at Kadamattam, Muttuchira and at St.Thomas Mount, in Mylapore. and throughout Malabar coast has inscriptions in Pahlavi and Syriac. The earliest is the small cross at Kottayam dated 7th century.[citation needed]

Persian bishops in Malabar

[edit]In 829 CE, the Udayamperoor (Diamper) church was built.

- Kadamattathu Kathanar

A priest (or bishop) from Persia Abo came to Kadamattom. With the help of a widow and her son, he built a small hut and lived there. He called the boy Poulose. Abo taught him Syriac and later ordained him as a deacon. After this deacon Poulose disappeared for twelve years. It is said that he was a well known exorcist. He is well known in Kerala as Kadamattathu Kathanar. Abo died and was buried in Thevalakara church (now St. Mary's Orthodox Church).[99][100]

History of Syro-Malabar Churches in India

[edit]

Visits from Rome to Malabar

[edit]There are many accounts of visits from Rome, before the arrival of Portuguese.

John of Monte Corvino, was a Franciscan missionary who traveled from Persia and moved down by sea to India, in 1291[101]

Odoric of Pordenone who arrived in India in 1321. He visited Malabar, landing at Pandarani (20 m. north of Calicut), at Cranganore, and at Kulam or Quilon.[102]

Jordanus, a Dominican, followed in 1321–22. He reported to Rome, apparently from somewhere on the west coast of India, that he had given Christian burial to four martyred monks.[101] Jordanus, between 1324 and 1328 (if not earlier), probably visited Kulam and selected it as for his future work. He was appointed a bishop in 1328 and nominated by Pope John XXII in his bull Venerabili Fratri Jordano to the see of Columbum or Kulam (Quilon) on 21 August 1329. This diocese was the first in the whole of the Indies, with jurisdiction over modern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burma, and Sri Lanka.[103]

In 1347, Giovanni de' Marignolli visited Malabar.[104]

Another prominent Indian traveler was Joseph, priest over Cranganore. He journeyed to Babylon in 1490 and then sailed to Europe and visited Portugal, Rome, and Venice before returning to India. He helped to write a book about his travels titled The Travels of Joseph the Indian which was widely disseminated across Europe.[101]

Medieval period

[edit]Prior to the Portuguese arrival in India in 1498, the Church of the East's See of Seleucia-Ctesiphon provided "Prelates" to the Saint Thomas Christians in India.[citation needed] This practise continued even after the arrival of the Portuguese until the Synod of Diamper (held in Udayamperoor) in 1599.[citation needed]

There are many accounts of missionary activities before the arrival of Portuguese in and around Malabar. John of Monte Corvino was a Franciscan sent to China to become prelate of Peking about the year 1307. He traveled from Persia and moved down by sea to India in 1291, to the South India region or "Country of St. Thomas".[101] There he preached for thirteen months and baptized about one hundred persons. From there Monte Corvino wrote home, in December 1291 (or 1292). That is one of the earliest noteworthy accounts of the Coromandel coast furnished by any Western European. Traveling by sea from Mailapur, he reached China in 1294, appearing in the capital "Cambaliech" (now Beijing)[105]

Odoric of Pordenone arrived in India in 1321. He visited Malabar, touching at Pandarani (20 m. north of Calicut), at Cranganore, and at Kulam or Quilon, proceeding thence, apparently, to Ceylon and to the shrine of St. Thomas at Mailapur, South India. He writes he had found the place where Thomas was buried.[102]

Jordanus, a Dominican, followed in 1321–22. He reported to Rome, apparently from somewhere on the west coast of India, that he had given Christian burial to four martyred monks.[101] Jordanus, between 1324 and 1328 (if not earlier), probably visited Kulam and selected it as the best centre for his future work; it would also appear that he revisited Europe about 1328, passing through Persia, and perhaps touching at the great Crimean port of Soidaia or Sudak. He was appointed a bishop in 1328 and nominated by Pope John XXII in his bull Venerabili Fratri Jordano to the see of Columbum or Kulam (Quilon) on 21 August 1329. This diocese was the first in the whole of the Indies, with jurisdiction over modern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burma, and Sri Lanka.[103]

Either before going out to Malabar as bishop, or during a later visit to the west, Jordanus probably wrote his Mirabilia, which from internal evidence can only be fixed within the period 1329–1338; in this work he furnished the best account of Indian regions, products, climate, manners, customs, fauna and flora given by any European in the Middle Ages – superior even to Marco Polo's. In his triple division of the Indies, India Major comprises the coast from Malabar to Cochin China; while India Minor stretches from Sindh (or perhaps from Baluchistan) to Malabar; and India Tertia (evidently dominated by African conceptions in his mind) includes a vast undefined coast-region west of Baluchistan, reaching into the neighborhood of, but not including, Ethiopia and Prester John's domain.[103]

In 1347, Giovanni de' Marignolli visited the shrine of St Thomas in South India, and then proceeded to what he calls the kingdom of Saba, and identifies with the Sheba of Scripture, but which seems from various particulars to have been Java. Taking ship again for Malabar on his way to Europe, he encountered great storms.[104]

Another prominent Indian traveler was Joseph, priest over Cranganore. He journeyed to Babylon in 1490 and then sailed to Europe and visited Portugal, Rome, and Venice before returning to India. He helped to write a book about his travels titled The Travels of Joseph the Indian which was widely disseminated across Europe.[101]

When the Portuguese arrived on the Malabar Coast, the Christian communities that they found there had had longstanding traditional links with the See of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia.[citation needed]

During the subsequent period, in 1552, a split occurred within the Assyrian Church of the East forming the Chaldean Church, the latter entered into communion with Rome. After the split each church had its own patriarch; the Chaldean Church was headed by the Patriarch Yohannan Sulaqa (1553–1555). Both claim to be the rightful heir to the East Syriac tradition. It is difficult to see the precise influence of this schism on the Church of Malabar as there was always overtones to Rome in earlier centuries. Apparently, both parties sent bishops to India.[citation needed]

The last East Syriac Metropolitan before the schism, Jacob (1504–1552), died in 1552. Catholicos Simeon VII Denkha sent a prelate to India, in the person of Abraham, who was later to be the last Syrian Metropolitan of Malabar, after having gone over to the Chaldaean side. It is not known when he arrived in Malabar, but he must have been there already by 1556. Approximately at the same time, Chaldaean Patriarch Abdisho IV (1555–1567), the successor of Yohannan Sulaqa (murdered in 1555), sent the brother of John, Joseph, to Malabar as a Chaldaean bishop; although consecrated in 1555 or 1556, Joseph could not reach India before the end of 1556, nor Malabar before 1558. He was accompanied by another Chaldaean bishop, Eliah.[citation needed]

Colonialism and St Thomas Christians

[edit]Portuguese

[edit]The Portuguese erected a Latin diocese in Goa (1534) and another at Cochin (1558) in the hope of bringing the Thomas Christians under their jurisdiction. In a Goan Synod held in 1585 it was decided to introduce the Latin liturgy and practices among the Thomas Christians.[citation needed]

Aleixo de Menezes, Archbishop of Goa from 1595 until his death in 1617 decided to bring the Kerala Christians to obedience after the death of Bishop Abraham (the last Syrian Metropolitan of Malabar, laid to rest at St. Hormis church, Angamaly), an obedience that they conceived as complete conformity to the Roman or ‘Latin’ customs. This meant separating the Nasranis not only from the Catholicosate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, but also from the Chaldaean Patriarchate of Babylon, and subjecting them directly to the Latin Archbishopric of Goa.[citation needed]

The Portuguese refused to accept the legitimate authority of the Indian hierarchy and its relation with the East Syriac Christians, and in 1599 at the Synod of Diamper (held in Udayamperur), the Portuguese Archbishop of Goa imposed a large number of Latinizations. The Portuguese succeeded in appointing a Latin bishop to govern the Thomas Christians, and the local Christians’ customs were officially anathematised as heretical and their manuscripts were condemned to be either corrected or burnt. The Portuguese padroado (’patronage’) was extended over them. From 1599 up to 1896 these Christians were under the Latin Bishops who were appointed either by the Portuguese Padroado or by the Roman Congregation of Propaganda Fide. Every attempt to resist the latinization process was branded heretical by them. Under the indigenous leader, archdeacon, the Thomas Christians resisted, but the result was disastrous.[citation needed]

The oppressive rule of the Portuguese padroado provoked a violent reaction on the part of the indigenous Christian community. The first solemn protest took place in 1653, known as the Koonan Kurishu Satyam (Coonan Cross Oath). Under the leadership of Archdeacon Thomas, a part of the Thomas Christians publicly took an oath in Matancherry, Cochin, that they would not obey the Portuguese bishops and the Jesuit missionaries. In the same year, in Alangad, Archdeacon Thomas was ordained, by the laying on of hands of twelve priests, as the first known indigenous Metropolitan of Kerala, under the name Mar Thoma I.[citation needed]

After the Coonan Cross Oath, between 1661 and 1662, out of the 116 churches, the Catholics claimed eighty-four churches, and the Archdeacon Mar Thoma I with thirty-two churches. The eighty-four churches and their congregations were the body from which the Syro Malabar Catholic Church have descended. The other thirty-two churches and their congregations were the body from which the Syriac Orthodox (Jacobites and Orthodox), Thozhiyur (1772), Mar Thoma (Reformed Syrians) (1874), Syro Malankra Catholic Church have originated.[106][107] In 1665, Gregorios Abdul Jaleel, a Bishop sent by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch arrived in India.[106][108] This visit resulted in the Mar Thoma faction claiming spiritual authority of the Antiochean Patriarchate and gradually introduced the West Syriac liturgy, customs and script to the Malabar Coast.

The arrival of Gregorios in 1665 marked the beginning of the association with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. Those who accepted the West Syriac theological and liturgical tradition of Gregorios became known as Jacobites. Those who continued with East Syriac theological and liturgical tradition and stayed faithful to the Synod of Diamper are known as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church in communion with the Catholic Church. They got their own Syro-Malabar Hierarchy on 21 December 1923 with the Metropolitan Augustine Kandathil as the Head of their Church.[109]

St. Thomas Christians by this process were divided into East Syriac and West Syriac branches.

On 4 May 1493, Pope Alexander VI granted Portugal the right to develop and send missions east of a demarcation line. When India had been reached, Portugal assumed that India was theirs to develop.[64]

On 20 May 1498, Vasco de Gama landed at Kappad near Kozhikode (Calicut).[64] In 1499, explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral landed at Kozhikode.[64] In 1500, Joseph, a priest, told the Pope Alexander VI, in an audience, that Indian Christians accept the Patriarch of Babylon as their spiritual leader.[64] On 26 November 1500, Franciscan Friars landed at Cochin.[64] On 7 November 1502 de Gama lands at Cochin.[64]

When the Portuguese first discovered the Christians, they felt satisfied that their centuries-old dream of discovering eastern Christians had been fulfilled. They set great hopes on the St.Thomas Christians. These Christians too on their part experienced a spontaneous relief and joy at the arrival of powerful Christians from the West and desired the newcomers' help to strengthen their own privileges in India. So their arrival was enthusiastically welcomed by the local church. In fact, when Vasco da Gama arrived at Cochin on his second voyage (1502), a delegation of Thomas Christians went and met him and implored protection. In 1503, Dominican Priests, Catholic missionaries, were in Kochi.[64] In 1503, Yabella, Denaha and Yakoob from Persia went to Kerala.[64] In 1503 the Portuguese commenced work on Cochin Fort and the Santa Cruz church.[64]

There were about thirty thousand St. Thomas families in Malabar in 1504.[citation needed][110] A letter written by East Syriac bishops announces the arrival of the Portuguese and the friendly relationship between them and the St. Thomas Christians.

Cordial relations continued for two decades. However, Portuguese penetrating into the interior where they actually came face-to-face with St. Thomas Christians, realized that these Christians were neither subject to Rome, nor were they following Church traditions. To their dismay they found that these Christians were followers of the East Syriac Church, and its bishops looked after them, and the Patriarch in Babylonia was considered their ecclesiastical superior. Since the Pope had granted to the Portuguese crown sovereign rights over the eastern lands which come under their sway, the Portuguese thought, that is their right to bring the Thomas Christians under their control. To achieve this aim, the Portuguese worked among the local church for one and a half centuries.

The Portuguese missionaries were ignorant of the Oriental traditions of the Indian Church. They were convinced that anything different from the Western Church was schismatic and heretical. Hence they wanted to Latinize the Syrian Christians of India. The visitors were appalled at the tolerance for other religions that was displayed by the locals.

In 1514, the Portuguese Padroado began. In 1514 Jewish people migrated from Kodungalloor to Kochi.[64] On 12 June 1514 the Portuguese colony at Funchal began their dominion over Christians in India.[64] On 23 December 1524 de Gama was buried at St. Francis Church, Fort Cochin.[64] In 1534 the Goa Catholic Diocese was erected. The parishes of Kannur, Cochin, Quilon, Colombo and Sao Tome (Madras) were part of it.[64] In 1540 Franciscan Vincent De Lagos started the Cranganore Seminary to train native priests.[64] On 6 May 1542 St. Francis Xavier, Apostolic Nuncio in the East, reached Goa. He was in Travancore between 1544 and 1545.[64] In 1548 a Dominican Monastery was founded in Cochin.[64] In 1549 Mar Abuna Jacob, a Chaldean Bishop, stayed at St. Antonio Monastery, Cochin.[64] In 1550, the first Jesuit House was erected in Kochi. Xavier died on 3 December 1552.[64]

During the subsequent period, in 1552, a split occurred within the Church of the East. Part of it joined Rome, so that besides the Catholicosate of the East another, Chaldean Patriarchate was founded, headed by the Patriarch Yohannan Sulaqa (1553–1555). Both claim to be the rightful heir to the East Syriac tradition. It is difficult to see the precise influence of this schism on the Church of Malabar as there was always overtones to Rome in earlier centuries. Apparently, both parties sent bishops to India.[citation needed]

The last East Syriac Metropolitan before the schism, Jacob (1504–1552), died in 1552. Catholicos Simeon VII Denkha sent a prelate to India, in the person of Abraham, who was later to be the last Syrian Metropolitan of Malabar, after having gone over to the Chaldaean side. It is not known when he arrived in Malabar, but he must have been there already by 1556. Approximately at the same time, Chaldaean Patriarch Abdisho IV (1555–1567) sent the brother of John, Joseph, to Malabar as a Chaldaean bishop. Although consecrated in 1555 or 1556, Joseph could not reach India before the end of 1556, nor Malabar before 1558. He was accompanied by another Chaldaean bishop, Eliah.[citation needed]

The Portuguese erected a Latin diocese in Goa in 1534 and another at Cochin in 1558 in the hope of bringing the Thomas Christians under their jurisdiction. In a Goan Synod held in 1585 it was decided to introduce the Latin liturgy and practices among the Thomas Christians.[citation needed]

The Portuguese built the Mattancherry Palace for the King of Cochin in 1555.[64] Pope Paul IV erected the Diocese of Cochin in 1557.[64] The canonization process of Francis Xavier began at Cochin.[64] The pope erected the 1565 Archdiocese of Angamaly in 1565.[64] The Jesuits started the seminary at Vaippicotta in 1577.[64] The Order of Augustinians reached Cochin in 1579.[64] In 1583, Bishop Abraham convoked a synod at Angamaly.[64]

Aleixo de Menezes, Archbishop of Goa from 1595 until his death in 1617 decided to bring the Kerala Christians under obedience after the death of Bishop Abraham (the last Syrian Metropolitan of Malabar, laid to rest at St. Hormis church, Angamaly), an obedience that they conceived as complete conformity to the Roman or ‘Latin’ customs. This meant separating the Nasranis not only from the Catholicosate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, but also from the Chaldaean Patriarchate of Babylon, and subjecting them directly to the Latin Archbishopric of Goa.[citation needed]

In 1597, Bishop Abraham, the last foreign Archbishop, died and was buried at St. Hormis church, Angamaly.[64]

The Synod of Diamper (1599)

[edit]Immediately after the death of the local bishop, Abraham, in 1599, Archbishop of Goa Aleixo de Menezes (1595–1617) convoked a Synod of Diamper and imposed Latinization and Western ecclesiastical traditions on the local Church of India. The Portuguese extended the Padroado Agreement in their evangelization programme over India, and therefore brought the Indian Church under Padroado jurisdiction.[111]

Menezes controlled the synod completely. He convoked it, presided over it, framed its decrees and executed them. The synod lasted for eight days. Almost all of the decrees were framed not in the synod after due discussion but 15 days or earlier prior to the meeting. Many of the decrees were framed after the Synod as the archbishop desired. The synodal decrees were passed by threats and terror methods, and autocratically as desired by the archbishop. The decrees forced conformance of the local church to the practices of the Roman Rite, in faith, polity, and discipline. It decreed submission to the pope. The Assyrian Patriarch of Babylon was condemned as a heretic and contact with him declared highly perilous inviting spiritual dangers. Additionally, The Malabar church was required to follow the norms declared by the Council of Trent. Priests must be celibate. The church had to be divided into parishes with the parish priest directly appointed by the Portuguese church authorities, replacing the native regime and bishopric. The powers and offices of the Roman bishop clashed with that of the archdeacon, so the latter's office was weakened, though there was still an incumbent. The church was required to abandon perceived "errors" which Jesuits believed had crept into its life from the Indian milieu. All Syriac books had to be handed over for burning so that no memory of those rites remained.

The Catholic Church appointed Francis Roz bishop of Angamaly in 1599.[64]

In August, 1600 Padroado rule was imposed on the Nasranis.[64] The church appointed Roz as the first Latin bishop of the St. Thomas Christians in 1601.[64] The church erected the Diocese of Cranganore in 1609. They suppressed the Archdiocese of Angamaly.[64] The Metropolitan of Goa limited the pastoral jurisdiction of Nasranis to Malabar in 1610.[64] A Dominican Seminary was started at Kaduthuruthy in 1624.[64] In 1626, Edappally Ashram was started for the religious community of St. Thomas Christians.[64]

About half of the people did not yield to Rome however, and although through this period the local church lacked adequate knowledge of theology and church history, it still maintained its Eastern character and ecclesiastical freedom. Among all the efforts that were undertaken to subdue the Thomas Christians, the efforts of the Jesuits, a religious order that had been framed in the context of reformation in Europe, were notable. They established a clergy training centre at Vaipikotta to train native clergy in Catholic style. The major architects behind the convocation, deliberations, framing and executing the decrees of the Synod, were the Vaipikotta Jesuits. Apart from these the administration of the local church was also entrusted to them. Until 1653, three Jesuit bishops ruled over the church executing the decrees of that Synod.

These events immediately followed the synod:

- The appointment of a Latin bishop over the Church of St.Thomas.

- Suppression of the Metropolitan status of Angamali and bringing of it as a subordinate under Goa.

- Padroado of the Portuguese was extended over the Thomas Christians.

- The Thomas Christians’ protest and Restoration of the Metropolitan status to Angamali and change of the place to Crangannore under the Latin bishop Roz.

The Synod has since been criticized by modern scholars, both ecclesiastical and secular. The impact of the synod on the local church was decisive. Catholicism was firmly established. The Synod was a turning point in the history of the Malabar Church. This relationship continued until the beginning of the second half of the 17th century.

Francis Roz was the first Catholic bishop over the Thomas Christians soon after the Synod. Because he had been the main architect behind the success of Udayamperoor, he was given the see over the local church. His rule lasted for 24 years. During that time he tried his best to Romanize the Thomas Christians in worship, administrative systems, customs, and discipline. Although the Synod had instructed the liturgy to be modified in accordance with the Roman custom, this was sternly opposed by the St.Thomas Christians. Therefore, Roz advocated a modified form of the ancient liturgy of the Saint Thomas Christians. He centralized in himself all authority reducing almost to nothing the powers of the archdeacon, palliyogams and kathanars of the St. Thomas’ Church. This authority continued during the episcopates of Roz' two successors, Stephen Britto (1624–1641) and Francis Garzia (1641–1659).

Archdeacon George of the Cross, who had been subordinated under Roz and Britto died in 1640. He was succeeded by his nephew, Archdeacon Thomas Parambil. Parambil did not cooperate with Garzia. Garzia used both ecclesiastical and civil powers to suppress the archdeacon.

The Portuguese refused to accept the legitimate authority of the Indian hierarchy and its relation with the East Syriac Christians, and in 1599 at the Synod of Diamper (held in Udayamperur), the Portuguese Archbishop of Goa imposed a large number of Latinizations. The Portuguese succeeded in appointing a Latin bishop to govern the Thomas Christians, and the local Christians’ customs were officially anathematised as heretical and their manuscripts were condemned to be either corrected or burnt. The Portuguese padroado (’patronage’) was extended over them. From 1599 up to 1896 these Christians were under the Latin Bishops who were appointed either by the Portuguese Padroado or by the Roman Congregation of Propaganda Fide. Every attempt to resist the latinization process was branded heretical by them. Under the indigenous leader, archdeacon, the Thomas Christians resisted, but the result was disastrous.

In 1562, a Syrian bishop named Ahatallah arrived in India, claiming to be a new Patriarch of India sent by the Pope. Deciding he was an impostor, the Portuguese arrested him and arranged for him to be sent to Europe for his case to be decided. Archdeacon Thomas strongly protested and demanded to see Ahatallah in Chochin, but the Portuguese refused, saying that he had already been sent to Goa. Ahatallah was never heard from in India again, and the rumor soon spread that the Portuguese had murdered him, fomenting discontent in the Saint Thomas Christian community and leading directly to the Coonan Cross Oath.[64][112]

The Coonan Cross revolt

[edit]The oppressive rule of the Portuguese padroado provoked a reaction on the part of the Christian community. The first protest took place in 1653, known as the Koonan Kurishu Satyam (Koonan Cross Oath). Under the leadership of Archdeacon Thomas, a part of the Thomas Christians publicly took an oath in Matancherry, Cochin, that they would not obey the Portuguese bishops and the Jesuit missionaries. In the same year, in Alangad, Archdeacon Thomas was ordained, by the laying on of hands of twelve priests, as the first known indigenous Metropolitan of Kerala, under the name Thoma I.

After the Coonan Cross Oath, between 1661 and 1662, out of the 116 churches, the Catholics claimed seventy-two churches, leaving Archdeacon Mar Thoma I thirty-two churches and twelve churches being shared.

In 1665, Gregorios Abdul Jaleel, a Bishop sent by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch arrived in India.[106][108] This visit resulted in the Mar Thoma party claiming spiritual authority of the Antiochean Patriarchate and gradually introduced the West Syriac liturgy, customs and script to the Malabar Coast.

The arrival of Gregorios in 1665 marked the beginning of a formal association of the Thomas Christians with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. Those who accepted the West Syriac theological and liturgical tradition of Gregorios became known as Jacobites. Those who continued with East Syriac theological and liturgical tradition and stayed faithful to the Synod of Diamper are known as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church in communion with the Catholic Church. They got their own Syro-Malabar Hierarchy on 21 December 1923 with the Metropolitan Augustine Kandathil as the Head of their Church.

St. Thomas Christians by this process got divided into East Syriac and West Syriac branches.

Further divisions

[edit]

In 1772 the West Syriac Christians under the leadership of Kattumangattu Abraham Koorilose, Metropolitan of Malankara, formed the Malabar Independent Syrian Church (Thozhiyur Sabha).[108]

From 1816 onwards, the Anglican C.M.S. missionaries helped the Malankara Church, through their Help Mission.[113] But on 16 January 1836, Metropolitan Dionysius IV of Cheppad, convened a Synod at Mavelikara, in protest against the interference of Anglicans in the affairs of the Malankara Church. There it was declared that Malankara Church would be subject to Syrian traditions and the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch.[114] The declaration resulted in the separation of the CMS missionaries from the communion with the Malankara Church.[113][115] However, a minority from the Malankara Church, who were in favour of the Reformed ideologies of the missionaries, stood along with them and joined the Anglican Church.[113][115] These Saint Thomas Anglicans, were the first Reformed group to emerge from the Saint Thomas Christian community and they worked along with the missionaries in their evangelical, educational and reformative activities.[113][116][117] By 1879, the Diocese of Travancore and Cochin of the Church of England was established in Kottayam.[118][119] On 27 September 1947, the Anglican dioceses in South India, merged with other Protestant churches in the region and formed the Church of South India (CSI); an independent United Church in full communion with all its predecessor denominations.[120][32] Since then, Anglican Syrian Christians have been members of the Church of South India and also came to be known as CSI Syrian Christians.[119]

In 1876, those who did not accept the authority of the Patriarch of Antioch remained with Thomas Athanasious and chose the name Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church. They removed a number practices introduced at The Synod of Diamper to the liturgy, practices and observances. In 1961, there was a split in this group with the formation of St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India.

In 1874 a section of Syro-Malabar Catholic Church from Thrissur came into communion with Patriarch of the Church of the East in Qochanis as a result of schism followed after the arrival of Bishop Rocos (1861) Elias Melus (1874) sent by the Patriarch of Chaldean. They follow the East Syriac tradition and are known as Chaldean Syrian Church.[citation needed]

However, in 1912 due to attempts by the Antiochean Patriarch to gain temporal powers over the Malankara Church, there was another split in the West Syriac community when a section declared itself an autocephalous church and announced the re-establishment of the ancient Catholicosate of the East in India. This was not accepted by those who remained loyal to the Patriarch. The two sides were reconciled in 1958 but again differences developed in 1975. Today the West Syriac community is divided into Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (in Oriental Orthodox Communion, autocephalous), Malankara Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church (in Oriental Orthodox Communion, under Antioch).[citation needed]

In 1930 a section of the Malankara Orthodox Church under the leadership of Ivanios and Theophilus came into communion with the Catholic Church, retaining all of the Church's rites, Liturgy, and autonomy. They are known as Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.[80]

Pentecostalism began to spread among Saint Thomas Christians from 1911, due to American missionary work.[121] The first Syrian Pentecostals came from Kerala Brethren, who were in turn mostly ex-Marthomites.[122][123][124] As the movement gained momentum, groups of people from all traditional St. Thomas Christian denominations became part of various emerging Pentecostal and evangelical fellowships.[123][125] Pentecostals from Syrian Christian background spearheaded the movement in Kerala and to a lesser extent in India, by providing the necessary leadership for establishing denominations like Indian Pentecostal Church of God, Assemblies of God in India, Church of God (Full Gospel) in India, The Pentecostal Mission and many other Neo-charismatic churches.[126][127][34][128]

Demography

[edit]Percentages Christian denominations in Kerala, including non-Saint Thomas Christians, in 2011[129][dead link]

Most Saint Thomas Christians live in their native Indian state of Kerala. A 2016 study under the aegis of the Govt. of Kerala, based on the data from 2011 Census of India and Kerala Migration Surveys, counted 2,345,911 Syro-Malabar Catholics, 493,858 Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox, 482,762 Malankara Orthodox Syrians, 465,207 Syro-Malankara Catholics and 405,089 Mar Thoma Syrians out of 6.14 million Christians in Kerala. The study also reported 274,255 Church of South India and 213,806 Pentecost/Brethren affiliates, which includes ethnic Syrians and others.[129][130] The Chaldean Syrian Church, St Thomas Evangelical Church of India and Malabar Independent Syrian Church are much smaller denominations.

Since the 1950s a sizeable population of St Thomas Christians have settled in Malabar region of Kerala following the Malabar Migration[citation needed]. Many work or have settled outside the State in cities like Mumbai, as well as outside India in West Asia, Europe, North America and Australia.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Church of the East in India

- Syriac Christianity

- Cochin Jews

- Goa Inquisition

- Latin Catholics of Malabar

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Medlycott (2005).

- ^ a b Fahlbusch (2008), p. 285.

- ^ a b The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- ^ Puthiakunnel, Thomas. "Jewish colonies of India paved the way for St. Thomas". In Menachery (1973).

- ^ a b c d Brock (2011a).

- ^ Baum & Winkler (2003), p. 52.

- ^ Bundy, David D. (2011). "Timotheos I". In Sebastian P. Brock; Aaron M. Butts; George A. Kiraz; Lucas Van Rompay (eds.). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "How did Timur change the history of the world?". DailyHistory.org.

- ^ "10 Terrors of the Tyrant Tamerlane". Listverse. 15 January 2018.

- ^ Frykenberg (2008), p. 111.

- ^ "Christians of Saint Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Frykenberg (2008), pp. 134–136.

- ^ Perczel, István (September 2014). "Garshuni Malayalam: A Witness to an Early Stage of Indian Christian Literature". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 17 (2): 291.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica (2011). Synod of Diamper. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ For the Acts and Decrees of the Synod cf. Michael Geddes, "A Short History of the Church of Malabar Together with the Synod of Diamper &c." London, 1694; Repr. in George Menachery (ed.), Indian Church History Classics, Vol.1, Ollur 1998, pp. 33–112.

- ^ F. L. Cross; E. A. Livingstone, eds. (2009) [2005]. "Addai and Mari, Liturgy of". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- ^ Neill, Stephen (1970). The Story of the Christian Church in India and Pakistan. Christian Literature Society. p. 36.

At the end of a period of twenty years, it was found that about two – thirds of the people had remained within the Roman allegiance; one – third stood by the archdeacon and had organized themselves as the independent Malankara Church, faithful to the old Eastern traditions and hostile to all the Roman claims.

- ^ a b Joseph (2011).

- ^ "Kerala Syrian Christian, Apostle in India, The tomb of the Apostle, Persian Church, Syond of Diamper – Coonan Cross Oath, Subsequent divisions and the Nasrani People". Nasranis. 13 February 2007.

- ^ Brock (2011b).

- ^ a b Varghese (2011).

- ^ George, V. C. The Church in India Before and After the Synod of Diamper. Prakasam Publications.

He wished to propagate Nestorianism within the community. Misunderstanding arose between him and the Assyrian Patriarch, and from the year 1962 onwards the Chaldean Syrian Church in Malabar has had two sections within it, one known as the Patriarch party and the other as the Bishop's party.

- ^ "Church of the East in India". Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Brock (2011c).

- ^ South Asia. Missions Advanced Research and Communication Center. 1980. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-912552-33-0.

The Mar Thoma Syrian Church, which represents the Protestant Reform movement, broke away from the Syrian Orthodox Church in the 19th century.

- ^ Fenwick (2011b).

- ^ "Ecumenical Relations". marthomanae.org. 9 May 2016. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Mission & Vision". St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India (steci) is an episcopal Church. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (18 April 2014). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-81-8475-396-7.

- ^ Neill (2002), pp. 247–251.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milic; Bromiley, Geoffrey William; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 687–688. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (21 September 2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 707. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- ^ Anderson, Allan; Tang, Edmond (2005). Asian and Pentecostal: The Charismatic Face of Christianity in Asia. OCMS. pp. 192–193, 195–196, 203–204. ISBN 978-1-870345-43-9.

- ^ a b Bergunder (2008), pp. 15–16, 26–30, 37–57.

- ^ "Thomas Christians: History & Tradition". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 November 2023.

- ^ Frykenberg (2008), p. 249.

- ^ Fahlbusch (2001), pp. 686–687.

- ^ Bergunder (2008), pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b John, Stanley J. Valayil C. (19 February 2018). Transnational Religious Organization and Practice: A Contextual Analysis of Kerala Pentecostal Churches in Kuwait. BRILL. p. 103. ISBN 978-90-04-36101-0.

- ^ a b Indian Pentecostal Church of God. "Our History". Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Neill (2004), p. [page needed].

- ^ "Biography of St. Thomas the Apostle". Naperville, IL: St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Stephen Andrew Missick. Mar Thoma: The Apostolic Foundation of the Assyrian Church and the Christians of St. Thomas in India. Journal of Assyrian Academic studies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- ^ a b c Menachery (1973).

- ^ Brown (1956).

- ^ Origin of Christianity in India - A Historiographical Critique by Dr. Benedict Vadakkekara. (2007). ISBN 81-7495-258-6.

- ^ Buchanan (1811); Menachery (1973, 1998); Mundadan (1984); Podipara (1970); Brown (1956).

- ^ Mathew (2003), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Menachery (1973, 1998); Brown (1956); Jacob (2001); Poomangalam (1998); Weil (1982).

- ^ Herbert (1638), p. 304.

- ^ Mathew (2003), p. 91.

- ^ Sarayu Doshi. ‘’India and Egypt’’. Bombay. 1993. p. 45.

- ^ a b Miller, J. Innes; (1960), Periplus Maris Erythraei The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

- ^ Mathew (2003), p. 54.

- ^ Mathew (2003), pp. 58–59.

- ^ History of Christianity. Vol.1. By Kenneth Scott Latourette, page 80

- ^ P.M. Jussay, The Jews of Kerala, University of Calicut, 2005. ISBN 978-81-7748-091-7 [1]

- ^ Bowler, Gerry. (2000). ‘’The World Encyclopedia of Christmas’’. Page 139.

- ^ a b c Menachery (1973, 1982, 1998); Brown (1956).

- ^ Tisserant (1957).

- ^ Menachery (1973, 1982, 1998); Mackenzie (1905); Nagam Aiya (1906); Medlycott (2005).

- ^ Orientale Conquistado (2 vols., Indian reprint, Examiner Press, Bombay