Maronites

الموارنة | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

c. 7–12 million[1][2][3][4][5][6]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3–4 million (incl. ancestry)[8] | |

| 1.2 million (incl. ancestry)[8] | |

| 750,000[9] | |

| 285,520[10][11][12] | |

| 167,190[9] | |

| 161,370[9] | |

| 96,100[9] | |

| 50,000–60,000[9] | |

| 25,000[13] | |

| 20,000[14] | |

| 13,170[9] | |

| 10,000[9] | |

| 6,350[nb 1][9] | |

| 5,850[15] | |

| 5,400[13] | |

| 5,300[13] | |

| 3,400[13] | |

| 2,250–3,000[15] | |

| 2,500[13] | |

| 2,470[13] | |

| 2,000[13] | |

| 1,000–1,500[9] | |

| Jerusalem and | 513[9] |

| Languages | |

| Lebanese Aramaic (Historical)[20][21] Classical Syriac[22][23] and Arabic[24][25][26] (Liturgical) | |

| Religion | |

| Maronite Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Lebanese Christians[27] | |

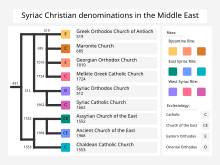

Maronites (Arabic: الموارنة, romanized: Al-Mawārinah; Syriac: ܡܖ̈ܘܢܝܐ, romanized: Marunoye) are a Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group[28] native to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant whose members belong to the Maronite Church. The largest concentration has traditionally resided near Mount Lebanon in modern Lebanon.[29] The Maronite Church is an Eastern Catholic sui iuris particular church in full communion with the pope and the rest of the Catholic Church.[30][31]

The Maronites derive their name from Saint Maron, a Syriac Christian whose followers migrated to the area of Mount Lebanon from their previous place of residence around the area of Antioch, and established the nucleus of the Maronite Church.[32]

Christianity in Lebanon has a long and continuous history. The spread of Christianity in Lebanon was very slow where paganism persisted, especially in the mountaintop strongholds of Mount Lebanon. During the 5th century AD, Saint Maron sent Abraham of Cyrrhus, often referred to as the Apostle of Lebanon, to convert the still significant pagan population of Lebanon to Christianity. The area's inhabitants renamed the Adonis River the Abraham River after Saint Abraham preached there.[33][34]

The early Maronites were Hellenized Semites, natives of Byzantine Syria who spoke Greek and Syriac,[35] yet identified with the Greek-speaking populace of Constantinople and Antioch.[36] They were able to maintain an independent status in Mount Lebanon and its coastline after the Muslim conquest of the Levant, keeping their Christian religion, and even their distinct Lebanese Aramaic[37] as late as the 19th century.[32] While Maronites identify primarily as native Lebanese of Maronite origin, many identify as Arab Christians.[38] Others identify as descendants of Phoenicians. Some Maronites argue that they are of Mardaite ancestry, while other historians, such as Clement Joseph David, the Syriac Catholic Archbishop of Damascus, reject this.[39][40]

Mass emigration to the Americas at the outset of the 20th century, famine during World War I that killed an estimated one third to one half of the population, the 1860 Mount Lebanon conflict and the Lebanese Civil War between 1975 and 1990 greatly decreased their numbers in the Levant; however Maronites today form more than one quarter of the total population of modern-day Lebanon. Though concentrated in Lebanon, Maronites also show presence in the neighboring Levant, as well as a significant part in the Lebanese diaspora in the Americas, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

The Maronite Church, under the patriarch of Antioch, has branches in nearly all countries where Maronite Christian communities live, in both the Levant and the Lebanese diaspora.

The Maronites and the Druze founded modern Lebanon in Ottoman Lebanon in the early 18th century, through the ruling and social system known as the "Maronite-Druze dualism" in the Ottoman Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate.[41] All Lebanese presidents, with the exception of Charles Debbas and Petro Trad, have been Maronites as part of a continued tradition of the National Pact, by which the prime minister has historically been a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of the National Assembly has historically been a Shi'ite.

Etymology

[edit]Maronites derive their name from Maron, a 4th-century Syriac Christian saint venerated by multiple Christian traditions. He is often conflated with John Maron, the first Maronite Patriarch, who ruled 685-707.[42][43]

History

[edit]

The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Lebanese people is a blend of many peoples that have come to rule the land over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview, Pierre Zalloua, a Lebanese biologist who took part in the National Geographic Society's Genographic Project, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions: "Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenician than another."[44]

Although Christianity existed in Roman Phoenice since the time of the Apostles, Christians were a minority among the majority pagans by the time Emperor Theodosius I issued The Edict of Thessalonica in 380 AD. The coastal cities of Tyre and Sidon remained prosperous during Roman rule, but Phoenicia had ceased to be the maritime empire it once was centuries ago and the north of Berytus (Beirut) and the mountains of Lebanon concentrated a big part of the intellectual and religious activities. Very few Roman temples were built in the coastal cities, hence the reason for the reign of paganism in the interior of the land.[45]

The Maronite movement reached Lebanon when in 402 AD Saint Maron's first disciple, Abraham of Cyrrhus, who was called the Apostle of Lebanon, realized that there were many non-Christians in Lebanon and so he set out to convert the Phoenician inhabitants of the coastal lines and mountains of Lebanon, introducing them to the way of Saint Maron.[46] In 451 AD, the Maronites followed the Council of Chalcedon, rejecting both monophysitism and miaphysitisim in favor of maintaining full communion with the then united Catholic Church. In 517 AD, a Chalcedonian conflict resulted in the massacre of 350 Maronite monks. Some sources detail the massacre was exacted under the orders of Monophysite Emperor Anastasius I, while others assign the responsibility to the Miaphysite Jacobite Syriacs.[42][47][48]

Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant in 637 AD, the Christians living in the low lands and coastal cities began to settle in the Mount Lebanon and to the coastal cities of the coast which did not particularly interest the Muslim Arabs; the area consisting of those regions extending from Sidon in the South and up to Batroun and the south of Tripoli in the north. The Arab conquerors settled in various cities of the coast to reduce Byzantine interference even though they were not interested in maritime trade. Since the mountains offered no attraction to them, the Christians continued to settle in the Mountains of Lebanon.[49][50] The Christians that chose to remain in the newly Arab-controlled areas and inhabited by the Arab invaders gradually became a minority and many of those converted to Islam in order to escape taxation and to further their own political and professional advancement.[51][clarification needed]

In 685 AD, St. John Maron became the first Patriarch of the Maronite Church. The appointing of a Patriarch made the Byzantine Emperor furious, which led to the persecution of the Maronites by the Byzantines. Following the Byzantine persecutions in the Orontes valley, many Maronite monks left their lands in the Orontes Valley and took refuge in the mountains of Lebanon.[52] The Maronite community migrated since the mid 7th century and through the 8th century, moving from the Orontes Valley in central Syria to Mount Lebanon, becoming the majority of the Christians in the hills around Tripoli and Byblos by the 10th century.[53]

The Maronites managed then to become "civilly semiautonomous" where they settled[42][54][55] and kept speaking Lebanese Aramaic[56] in daily life and Classical Syriac for their liturgy.

The Maronites welcomed the conquering Christians of the First Crusade in 1096 AD.[57] Around the late 12th century, according to William of Tyre, the Maronites numbered 40,000 people.[58] During the several centuries of separation from the rest of the Christian world, they often claim to have been in full communion with the Catholic Church throughout.

Despite this the majority of the accounts of those interacting with them at the time indicate that they were monothelites; notable figures from the era such as the medieval historian Jacques de Vitry and the chronicler of the Pope, William of Tyre affirming this, the latter of which (William Tyre) recorded both their kindness upon receiving him and the monothelitic views of which they recanted, stating; "The heresy of Maro and his followers is and was that in our Lord Jesus Christ, there exists and did exist from the beginning one will and one energy only, as may be learned from the sixth council, which as is well known, was assembled against them and in which they suffered sentence of condemnation. Now however...they repented all of these heresies and returned to the catholic church".[59][16] The Maronites have also had a presence in Cyprus since the early 9th century and many Maronites went there following the Sultan Saladin's successful Siege of Jerusalem in 1187 AD.[60]

During the papacy of Pope Gregory XIII (1572–1585), steps were taken to bring the Maronites still closer to Rome. The Maronite College in Rome (Pontificio Collegio dei Maroniti) being founded by Gregory XIII in 1584.[61] By the 17th century, the Maronites had developed a strong natural liking for Europe – particularly France.[62]

The relationship between the Druze and Christians has been characterized by harmony and peaceful coexistence,[63][64][65][66] with amicable relations between the two groups prevailing throughout history, with the exception of some periods, including 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war.[67][68] In the 19th century, thousands of Maronites were massacred by the Lebanese Druze during the 1860 conflict. According to some estimates about 11,000 Lebanese Christians (including Maronites) were killed; over 4,000 died from hunger and disease as a result of the war.[69]

After the 1860 massacres, many Maronites fled to Egypt. Antonios Bachaalany, a Maronite from Salima (Baabda district) was the first emigrant to the New World, where he reached the United States in 1854 and died there two years later.[70]

Population

[edit]Lebanon

[edit]

According to the Maronite church, there were approximately 1,062,000 Maronites in Lebanon in 1994, where they constitute up to 32% of the population.[71] Under the terms of the National Pact agreement between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, the president of the country must be a Maronite Christian.[72]

Syria

[edit]There is also a small Maronite Christian community in Syria. In 2017, the Annuario Pontificio reported that 3,300 people belonged to the Archeparchy of Aleppo, 15,000 in the Archeparchy of Damascus and 45,000 in the Eparchy of Lattaquié).[73] In 2015, the BBC placed the number of Maronites in Syria at between 28,000 and 60,000.[74]

Cyprus

[edit]Maronites first migrated to Cyprus in the 8th century, and there are approximately 5,800 Maronites on the island today, the vast majority in the Republic of Cyprus.[17] The community historically spoke Cypriot Maronite Arabic,[75][76] but today Cypriot Maronites speak the Greek language, with the Cypriot government designating Cypriot Maronite Arabic as a dialect.[17]

Israel and Palestine

[edit]A Maronite community of about 11,000 people lives in Israel.[77] The 2017 Annuario Pontificio reported that 10,000 people belonged to the Maronite Catholic Archeparchy of Haifa and the Holy Land and 504 people belonged to the Exarchate of Jerusalem and Palestine.[73]

Diaspora

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Maronite Church |

|---|

|

| Patriarchate |

| Religious orders and societies |

| Communities |

| Languages |

| History |

| Related politics |

|

|

According to various sources the Maronite diaspora is estimated to be somewhere between 7 and 12 million individuals, much larger than the Maronite population living in their historic homelands in Lebanon, Syria, Cyprus, Israel, and Palestine.[2][6] Due to cultural and religious assimilation, especially in the Americas, many Maronites or those of Maronite descent might not identify as Maronite or are unaware of their Maronite heritage.[78][79]

According to the Annuario Pontificio, in 2020 the Eparchy of San Charbel in Buenos Aires, Argentina, had 750,000 members; in 2021 the Eparchy of Our Lady of Lebanon of São Paulo, Brazil, had 521,000 members; in 2020 the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Sydney, Australia, had 161,370 members; in 2020 the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Montreal, Canada, had 94,300 members; in 2021 the Eparchy of Our Lady of the Martyrs of Lebanon in Mexico had 167,190 members; in 2021 the Eparchy of Our Lady of Lebanon of Los Angeles in the United States had 47,480 members; in 2020 and the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Brooklyn in the United States had 23,939 members.[9]

According to the Annuario Pontificio, 51,520 people belonged to the Maronite Catholic Eparchy of Our Lady of Lebanon of Paris in 2021.[9] In Europe, some Belgian Maronites are involved in the trade of diamonds in the diamond district of Antwerp.[80]

According to the Annuario Pontificio, 74,900 belonged to the Apostolic Exarchate of West and Central Africa (Nigeria) in 2020.[9] The Diocese is centered in Ibadan, Nigeria and covers the countries of Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger. Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.[81]

Role in politics

[edit]Lebanon

[edit]In 1920, Maronites played a key role in the establishment of Greater Lebanon by the French Mandate.[82] With only two exceptions, all Lebanese presidents have been Maronites as part of a tradition that persists as part of the National Pact, by which the Prime Minister has historically been a Sunni Muslim and the Speaker of the National Assembly has historically been a Shia Muslim.

A unique feature of the Lebanese system is the principle of "confessional distribution": all religious community has an allotted number of deputies in the Parliament. Thirty-four seats in parliament are reserved for Maronites. The largest party is the Lebanese Forces that receives most of its support from the Maronite Christians but it also supported by other Christian sects throughout the country. It currently has 19 seats in parliament, 11 of them being Maronite. The Phalange Party is a Christian-based political party of Maronite majority and former militia. it currently holds 4 of the 128 seats in parliament, all of which are Christian. As a militia, it played a pivotal role during the Lebanese Civil War as it controlled its own Maronite canton (Marounistan) as part of the Lebanese Front. The party is also led by the Gemayel family, a notable Maronite family based in the regions of Achrafieh and Metn which carries the legacy of Pierre and Bashir Gemayel.

The Free Patriotic Movement is Christian-based political party which follows the agenda of former president Michel Aoun. It currently holds 17 seats of the 128 seats in Lebanon's parliament. The party has large support in Christian districts like Batroun and Jezzine. Other smaller Maronite-based parties that only receive local support includes, the Marada Movement, National Liberal Party and Independence Movement.

Israel and Palestine

[edit]People born into Christian families or clans who have either Aramaic or Maronite cultural heritage are considered an ethnicity separate from Israeli Arabs and since 2014 can register themselves as Arameans.[83] The Christians who have applied so far for recognition as Aramean are mostly Galilean Maronites.

In addition, some 500 Christian adherents of the Syriac Catholic Church in Israel are expected to apply for the recreated ethnic status, as well as several hundred Aramaic-speaking adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[84] Though supported by Gabriel Naddaf, the move was condemned by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, which described it as "an attempt to divide the Palestinian minority in Israel".[85]

This recognition comes after about seven years of activity by the Aramean Christian Foundation in Israel, led by IDF Major Shadi Khalloul Risho and the Israeli Christian Recruitment Forum, headed by Father Gabriel Naddaf of the Greek-Orthodox Church and Major Ihab Shlayan.[86] Shadi Khalloul Risho is also a member of the Israeli right-wing Yisrael Beiteinu party, and was placed 15th in the 2015 parliamentary elections in the party's member list; the party however received only 5 seats.

Religion

[edit]

The Maronites belong to the Maronite Syriac Church of Antioch, an Eastern Catholic Syriac church using the Antiochian Rite, which traces its foundation to Maron, an early 4th-century Syriac monk venerated as a saint. The Maronite Church had returned to its communion with Rome since 1180 A.D., although the official view of the contemporary Maronite Church is that it had never accepted either the Monophysitic views held by their Syriac neighbours, which were condemned in the Council of Chalcedon, or the failed compromise doctrine of Monothelitism (despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary of the latter claim being found in contemporary and medieval sources, with evidence that they were staunchly Monothelites for several centuries, beginning in the early 7th century after their rejection of the sixth ecumenical council).[87][59] The Maronite Patriarch is traditionally seated in Bkerke north of Beirut.

Cultural identity

[edit]The Maronite Church belongs to the Syriac Christian tradition and to the West Syriac Rite; Classical Syriac remains the liturgical language of the Maronite Church,[88] alongside Arabic.[24] The Maronite community is generally considered culturally part of the Christian Arab community and of the Arab world.[49] Between the 19th and 20th centuries, within the Nahda and the Mahjar, many Maronite intellectuals contributed to the formation of modern Arab identity and Arab nationalism. Key figures include Naguib Azoury, Ameen Rihani and Kahlil Gibran. Youssef Bey Karam, a Maronite leader during the 19th century, in a letter to Emir Abdelkader encouraged him to liberate all Arabs from the Ottoman Empire and then establishing an Arab Union.[89][90]

During the 20th century most of the Maronite elite in Lebanon favored the development of a primarily Lebanese identity and its separation from the Pan-Arabist one, in favor of a policy that would bring the country closer to the Western world.[49] Some Lebanese intellectuals, mainly Maronites, theorized Phoenicianism, which asserted the descent of the Lebanese people from the Phoenicians.[91][92] Key figures of this movement were Charles Corm, Michel Chiha and Said Aql.[93] Aql and Etienne Saqr went as far as voicing anti-Arab views. In his book the Israeli writer Mordechai Nisan quoted Aql as saying; "I would cut off my right hand, and not associate myself to an Arab."[94] Aql believed in emphasizing the Phoenician legacy of Lebanon and had promoted the use of the Lebanese Arabic dialect written in a modified Latin alphabet, rather than the Arabic one. Phoenicianism is still disputed by many Arabist scholars who have on occasion tried to convince its adherents to abandon their claims as false, and to embrace and accept the Arab identity instead.[95] Since the civil war and the Taif agreement, Lebanese Phoenicianism is restricted to a small group.[93]

On an Al Jazeera special dedicated to the political Christian clans of Lebanon and their struggle for power in the 2009 election entitled, "Lebanon: The Family Business", the issue of identity was brought up on several occasions. Sami Gemayel, of the Gemayel clan, stated he did not consider himself an Arab but instead identified himself as a Syriac Christian, going on to explain that to him and many Lebanese the "acceptance" of Lebanon's "Arab identity" according to the Taif Agreement was not something that they "accepted" but instead were forced into signing through pressure. In a speech to a crowd of Kataeb supporters Gemayel declared that he felt there was importance in Christians in Lebanon finding an identity and went on to state what he finds identification with as a Lebanese Christian, concluding with a purposeful exclusion of Arabism in the segment.[96]

Maronite Deacon Soubhi Makhoul, administrator for the Maronite Exarchate in Jerusalem, said "The Maronites are Arabs, we are part of the Arab world. And although it's important to revive our language and maintain our heritage, the church is very outspoken against the campaign of these people."[97] Suleiman Frangieh, leader of the Marada Movement, has often affirmed the belonging of the Maronite community to the Arab world and the importance of its adherence to Arabism.[98][99]

In Israel, some members of the local Maronite community have adopted an Aramean identity and organized linguistic revitalization programs. The Aramean identity was officially recognized by the Israeli Minister of the Interior in 2014, allowing certain Christian families to register their ethnicity as "Aramean" rather than "Arab" or "Unclassified."[100] A slight majority of the Maronites in Israel identify themselves as Arabs; the Arab identity is prevalent especially among the young and among women.[101]

See also

[edit]- Christianity in Lebanon

- List of Maronites

- Maronite politics

- East Beirut canton

- Maronite Christianity in Lebanon

- Syriac Christianity

Notes

[edit]- ^ Numbers were higher before the 1956–1957 exodus and expulsions from Egypt

- ^ Neo-Aramaic has been partially revitalized by some Maronite activists in Israel, especially in Jish

References

[edit]- ^ Dagher, Carole (2000). Bring Down the Walls: Lebanon's Post-War Challenge. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. doi:10.1057/9780230109193. ISBN 978-0-312-29336-9.

[E]stimates vary between 16 million émigrés of Lebanese descent and 4 million. But they all agree on the fact that Christians amount to between 65 percent and 70 percent, among whom Maronites alone represent roughly 48 percent of this diaspora, and are thus the largest 'Lebanese' community abroad

- ^ a b Gemayel, Boutros. "Archbishop of the Maronite Church in Cyprus". maronite-institute.org. The Maronite Research Institute.

There are reportedly over seven million Maronites alone living in Brazil, the United States of America, South America, Canada, Africa, Europe and Australia.

- ^ Moussa, Gracia (22 September 2014). "Maronites: the face of Christians in the Middle East". geopolitica.info. L’Associazione Geopolitica.info.

The number of Maronites abroad is estimated to be 8 million.

- ^ "The Maronite Church 'A bridge between East and West'". cmc-terrasanta.org. Christian Media Center. 10 June 2016.

There are more than 10 million Maronites around the world

- ^ Bejjani, Elias (10 February 2008). "St. Maroun & His followers the Maronites". Canadian Lebanese Coordinating Council. Archived from the original on 17 May 2023.

Every year, on the ninth of February, more than ten million Maronites from all over the world celebrates St. Maroun's day.

- ^ a b Hugi, Jacky (15 March 2013). "Aramaic Language Project in Israel Furthers Recognition of Maronites". al-monitor.com. Al-Monitor, LLC.

There are 12 million Maronites in the world today.

- ^ Burger, John (10 September 2020). "Christians in Lebanon: A short history of the Maronite Church". Aleteia. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ a b Tu, Janet (17 November 2001). "Maronite Mass gets trial run at Shoreline parish". seattletimes.com. The Seattle Times.

Today there are about 7 million Maronites worldwide, most of them in Brazil (with 3 million or 4 million) and the United States (with 1.2 million Maronites, and 83 Maronite churches).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Current Maronite Dioceses". Catholic Hierarchy. David M. Cheney. 2023.

- ^ "Henry Laurens : 'la France et le Liban sont comme les membres d'une famille recomposée'". 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ iLoubnan (2009). "Geographical distribution of Lebanese diaspora". Ya Libnan. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "La France au Liban Ambassade de France à Beyrouth". Ambassade de France à Beyrouth. Archived from the original on 11 December 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Statistics". Maronite Heritage. Fr. Antonio Elfeghali. 9 February 2011.

- ^ "The Struggle Of The Christian Lebanese For Land Ownership In South Africa". The Marionite Research Institute. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Parishes". annunciation-eparchy. Maronite Eparchy – Africa. 2023.

- ^ a b "Maronite church | Meaning, History, Liturgy, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. 14 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Educational Policies that Address Social Inequality: Country Report: Cyprus Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, p. 4.

- ^ Judith Sudilovsky (22 June 2012). "Aramaic classes help Maronites in Israel understand their liturgies". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Daniella Cheslow, (2014-06-30) Maronite Christians struggle to define their identity in Israel, The World, Public Radio International. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ Hitti, Philip (1957). Lebanon in History. India: Macmillan and Co Ltd. p. 336.

Being largely mountaineers and still Syriac-speaking the Maronite community was evidently looked upon as a minority ethnic group rather than a separate denomination.

- ^ Schulze, Kirsten E; Stokes, Martin; Campell, Colm (1996). Nationalism, Minorities and Diasporas: Identities and Rights in the Middle East. Magee College: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 162. ISBN 9781860640520.

This identity was underlined by Christian resistance to adopting Arabic as the spoken language. Originally they had spoken Syriac but increasingly opted to use "Christian" languages such as Latin, Italian, and most importantly, French.

- ^ Iskandar, Amine (27 February 2022). "About the origin of the Lebanese language (I)". syriacpress.com. Syriacpress.

The Lebanese have never spoken Ktovonoyo, but it was and is the liturgical language of the Syriac Maronite Church. This language was taught in their schools until 1943 and it is the only language they wrote and the one they still sing in the form of hymns. It is the language taught in schools that defines the identity of the people and their land.

- ^ Iskandar, Amine (26 November 2021). "Syriac Identity of Lebanon part 13: The Three Syriac Scripts". syriacpress.com. Syriacpress.

- ^ a b Language Structure and Environment: Social, Cultural, and Natural Factors. John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2015. p. 168. ISBN 9789027268730.

- ^ Maronite Church in Syria, The

- ^ Maronite liturgy draws from Eastern and Western traditions, Catholics and cultures

- ^ Haber, Marc; Gauguier, Dominique; Youhanna, Sonia; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Botigué, Laura; Platt, Daniel; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth; Soria-Hernanz, David; Wells, R; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Comas, David; Zalloua, Pierre (28 February 2013). "Genome-Wide Diversity in the Levant Reveals Recent Structuring by Culture". PLOS Genetics. 9 (2): e1003316. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003316. PMC 3585000. PMID 23468648.

- ^

- Fattouh, Emily Michelle (2018). "Adaptive Leadership and the Maronite Church". M.A. In Leadership Studies: Capstone Project Papers. Digital USD.

The continuation of the presence of the Maronite Christian Church in the United States connects people to a larger ethnic community, and most importantly, helps preserve cultural, social, and religious traditions.

- "Maronites - Minority Rights Group". minorityrights.org. Minority Rights Group International. 2021.

- "Maronites, Christians of the Middle East". stgeorgesa.org. St. George Maronite Catholic Church. 2021.

Maronites started their own churches wherever they settled in the United States, a sign of their attachment to their ethnic and religious identities.

- Ghosn, Margaret; Engebretson, Kath (2010). "National Identity of a Group of Young Australian Maronite Adults" (PDF). crucibleonline.net. Crucible Journal.

Their religious identity was part of an ethnic identification that was rigorously maintained as a result of the turmoil surrounding the history and current status of Maronites in Lebanon.

- Demosthenous, Areti (2012). "The Maronites of Cyprus: From ethnicism to transnationalism". Gamer. I (1): 61–72.

If we take as an example the Maronite community of Cyprus, it is considered as a minority by all international standards and they match perfectly the definition for national and ethnic minorities adopted by the United Nations and the Council of Europe.

- Mavrides, Mario; Maranda, Michael (1999). "The Maronites of Cyprus: A Community in Crisis". Journal of Business & Society. 12 (1): 78–94.

The Maronite ethnic identity is centred on their religion and on a historical sense of being a distinct group.

- Labaki, Georges T. (2014). "The Maronite Church in the United States, 1854–2010". U.S. Catholic Historian. 32 (1): 71–85. doi:10.1353/cht.2014.0001. JSTOR 24584748. S2CID 153455080.

Many petitioned the patriarch to assign Maronite priests to serve in the U.S., stressing the importance of preserving Maronite spirituality and traditions and the urgent need to convey faith, language, and ethnic traditions to the children of immigrants.

- Fattouh, Emily Michelle (2018). "Adaptive Leadership and the Maronite Church". M.A. In Leadership Studies: Capstone Project Papers. Digital USD.

- ^ Hagopian, Elaine C. (October 1989). "Maronite Hegemony to Maronite Militancy: The Creation and Disintegration of Lebanon". Third World Quarterly. 11 (4). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 104. doi:10.1080/01436598908420194. JSTOR 3992333. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Moubarak, Andre (2017). One Friday in Jerusalem. Jerusalem, Israel: Twin Tours & Travel Ltd. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-9992-4942-0.

- ^ Malone, Joseph J. The Arab Lands of Western Asia, Prentice-Hall, 1973, p. 7 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Mannheim, I (2001). Syria & Lebanon handbook: the travel guide. Footprint Travel Guides. pp. 652–563. ISBN 978-1-900949-90-3.

- ^ El-Hāyek, Elias (1990). Michael Gervers and Ramzi Jibran Bikhazi (ed.). Conversion and Continuity: Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. pp. 408–409. ISBN 0-88844-809-0. ISSN 0228-8605.

- ^ AbouZayd, Shafiq (1993). Iḥidayutha: A Study of the Life of Singleness in the Syrian Orient, from Ignatius of Antioch to Chalcedon 451 A.D. Oxford: Aram Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies. p. 304. ISBN 9780952077602.

- ^ Dr. Amine Jules Iskandar (9 June 2020). "Syriac Identity of Lebanon – part 4: Why is Spoken Lebanese a Syriac Dialect?". Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ "Lebanon in Crisis: Who Are the Maronites?". CNEWA. 13 August 2020.

- ^ Dr. Amine Jules Iskandar (27 February 2022). "About the origin of the Lebanese language (I)". Retrieved 16 November 2023.

Surien (West Syriac from Canaan) The third form is also part of West Syriac but is located further west

- ^ Williams, Victoria R. (2020). Indigenous Peoples: An Encyclopedia of Culture, History, and Threats to Survival [4 Volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 706. ISBN 9781440861185.

- ^ Moosa, Matti (2005). The Maronites in history. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-59333-182-5.

- ^ Suermann, Harald (1 July 2002). "Maronite Historiography and Ideology". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 54 (3): 129–148. doi:10.2143/jecs.54.3.1071. ISSN 0009-5141.

- ^ Deeb, Marius (2013). Syria, Iran, and Hezbollah: The Unholy Alliance and Its War on Lebanon. Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817916664.

the Maronites and the Druze, who founded Lebanon in the early eighteenth century.

- ^ a b c P.J.A.N. Rietbergen (2006). Power And Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies. Brill. p. 299. ISBN 9789004148932.

- ^ Moosa, Matti (2005). The Maronites in History. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-59333-182-5.

- ^ Maroon, Habib (31 March 2013). "A geneticist with a unifying message". Nature Middle East. Nature. doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2013.46.

- ^ Taylor, George (1967). "The Roman Temples of Lebanon (extract)". Dar el-Machreq Publishers.

- ^ El-Hāyek, Elias (1990). Michael Gervers and Ramzi Jibran Bikhazi (ed.). Conversion and Continuity: Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. ISBN 0-88844-809-0. ISSN 0228-8605.

- ^ "An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors>". Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Eastern Churches Review Volume 10. University of Minnesota: Holywell Books. 1978. p. 90.

- ^ a b c Mackey, Sandra (2006). Lebanon: A House Divided. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393352764. Cite error: The named reference ":1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Eparchy of St. Maron- Canada. "Origins of the Maronites".

- ^ Mackey, Sandra (2006). Lebanon: A House Divided. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393352764.

- ^ Jack Donnelly; Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann (1 January 1987). International Handbook of Human Rights. ABC-CLIO. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-3132-4788-0.

- ^ William Harris (2012). Lebanon: A History, 600–2011. OUP USA. p. 34. ISBN 9780195181111.

- ^ Rome and the Eastern Churches (revised ed.). Ignatius Press. 2010. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-5861-7282-4.

- ^ Michael Haag (2010). Templars: History and Myth: From Solomon's Temple to the Freemasons. Profile Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-8476-5251-5.

- ^ Mark A. Lamport; Mitri Raheb (2022). "The Maronite Church". Surviving Jewel The Enduring Story of Christianity in the Middle East. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 308. ISBN 9781725263215.

The origins of the Syriac-speaking Maronites, who are predominant in Lebanon are traced to Saint Maron (d. 410)…

- ^ James Minahan (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L–R (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1196. ISBN 978-0-3133-2111-5.

- ^ Kenneth M. Setton; Norman P. Zacour; Harry W. Hazard (1 September 1985). A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East (illustrated ed.). Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-2990-9144-6.

- ^ a b Crawford, Robert W. (1955). "William of Tyre and the Maronites". Speculum. 30 (2): 222–228. doi:10.2307/2848470. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2848470. S2CID 163021809.

- ^ Ernest Gellner (1985). Islamic Dilemmas: Reformers, Nationalists, Industrialization : The Southern Shore of the Mediterranean. Walter de Gruyter. p. 258. ISBN 978-3-1100-9763-4.

- ^ P.J.A.N. Rietbergen (2006). Power And Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies. Brill. p. 301. ISBN 9789004148932.

- ^ James Minahan (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L–R (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1196–1197. ISBN 978-0-3133-2111-5.

- ^ Hazran, Yusri (2013). The Druze Community and the Lebanese State: Between Confrontation and Reconciliation. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 9781317931737.

the Druze had been able to live in harmony with the Christian

- ^ Artzi, Pinḥas (1984). Confrontation and Coexistence. Bar-Ilan University Press. p. 166. ISBN 9789652260499.

.. Europeans who visited the area during this period related that the Druze "love the Christians more than the other believers," and that they "hate the Turks, the Muslims and the Arabs [Bedouin] with an intense hatred.

- ^ Churchill (1862). The Druzes and the Maronites. Montserrat Abbey Library. p. 25.

..the Druzes and Christians lived together in the most perfect harmony and good-will..

- ^ Hobby (1985). Near East/South Asia Report. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. p. 53.

the Druzes and the Christians in the Shuf Mountains in the past lived in complete harmony..

- ^ Fawaz, L.T. (1994). An Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520087828. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ Vocke, Harald (1978). The Lebanese war: its origins and political dimensions. C. Hurst. p. 10. ISBN 0-903983-92-3.

- ^ Johnson, Michael (2001). All Honourable Men. The Social Origins of War in Lebanon. London / New York: IB Tauris. p. 96.[ISBN missing]

- ^ "A Brief History of the Maronites". maronitefoundation.org. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Lebanon – International Religious Freedom Report 2008 U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on 2018-11-18.

- ^ United Nations Development Programme: Programme on Governance in the Arab Region : Elections : Lebanon Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ a b The Maronite Catholic Church (Patriarchate) Archived 2018-05-13 at the Wayback Machine in "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2017" in Annuario Pontificio 2017.

- ^ "Syria's beleaguered Christians". BBC News. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Maria Tsiapera (1969). A Descriptive Analysis of Cypriot Maronite Arabic. The Hague: Mouton and Company. p. 69.

- ^ Cyprus Ministry of Interior: European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages: Answers to the Comments/Questions Submitted to the Government of Cyprus Regarding its Initial Periodical Report Archived 19 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ Ami Bentov (26 May 2014). "Cardinal is first top Lebanese cleric in Israel". Associated Press. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Devis-Amaya, Esteban (May 2014). The construction of identity and community – performing ethnicity: who are the Colombian-Lebanese? (phd). University of Southampton. p. 1.

The large majority of them are descendants of Maronite Christians, though participation in religious services varies. It must be noted that my study does not cover all the individuals of Lebanese descent in Bogota, largely because they do not consciously include themselves, or are not included in this community. This is due to a combination of lack of identification with the community, lack of knowledge of their ancestry or the community, as well as social and religious differences

- ^ Khachan, Charles (2015). Ethnic Identity Among Maronite Lebanese in the United States. University of the Incarnate Word. p. 31.

Many Maronites became estranged from their culture. Today many efforts are being constructed to reconnect these descendants of the early immigrants with their motherland Lebanon and their Maronite Church. The main challenge faced by the Maronites in the United States is that of losing their ethnic and religious identity.

- ^ Ian Traynor (23 June 2009). "Recession takes the sparkle out of Antwerp's diamond quarter". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Maronite Diocese of Annunciation of Ibadan". gcatholic.org. 28 July 2023.

- ^ ""لبنان الكبير " حقيقة تاريخية أثبتها البطريرك الياس الحويك وكرّسها اللبنانيون بنضالاتهم المستمرة في الدفاع عن الوطن والقضايا العربية!". Al-Afkar. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Ministry of Interior to Admit Arameans to National Population Registry". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "אנחנו לא ערבים - אנחנו ארמים" (in Hebrew). Israel HaYom. 9 August 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Ariel (28 September 2014). "Israeli Greek Orthodox Church denounces Aramaic Christian nationality". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Israeli Christians Officially Recognized as Arameans, Not Arabs". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Moosa, M (2005). The Maronites in History. Gorgias Press LLC. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1-59333-182-5.

- ^ Shafiq Abouzayd (2018). "Chapter Thirty-Six: The Maronite Church". The Syriac World. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317482116.

- ^ Steppat, Fritz (1969). "Eine Bewegung unter den Notabeln Syriens 1877–1878: Neues Licht auf die Entstehung des Arabia hen Nationalismus". Zeitschrift: Supplementa (in German) (1). Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft; F. Steiner Verlag.

- ^ Ş. Tufan Buzpinar (1996). "Opposition to the Ottoman Caliphate in the Early Years of Abdülhamid II: 1877–1882". Die Welt des Islams. 36 (1): 59–89. ISSN 0043-2539.

- ^ Najem, Tom; Amore, Roy C.; Abu Khalil, As'ad (2021). Historical Dictionary of Lebanon. Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East (2nd ed.). Lanham Boulder: New York & London: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 345. ISBN 978-1-5381-2043-9.

- ^ El-Husseini, Rola (2012). Pax Syriana: Elite Politics in Postwar Lebanon. Syracuse University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8156-3304-4.

- ^ a b Asher Kaufman (2004). Reviving Phoenicia: The Search for Identity in Lebanon. I.B. Taurus. p. 36. ISBN 1-86064-982-3.

- ^ Frank Cass (2003). The Conscience of Lebanon. Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-8378-2.

- ^ Sami G. Hajjar, ed. (1985). The Middle East. E.J. Brill. p. 89. ISBN 90-04-07694-8.

- ^ "Lebanon: The family business". YouTube. Al Jazeera English. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Svetlova, Ksenia (12 October 2012). "Maronite Christians Seek To Revive Aramaic Language". The Forward. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "تيار المردة ينظم مهرجانا انتخابيا في بنشعي" (in Arabic). YouTube. MTV Lebanon News.

- ^ "سليمان فرنجية: نؤمن بالعروبة وبالحوار وبأفضل العلاقات مع الجميع.. ونعتز بموقفنا السياسي" (in Arabic). Al-Manar. 8 March 2023. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023.

- ^ Camelia Suleiman (2017). Politics of Arabic in Israel: A Sociolinguistic Analysis. Edinburgh University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781474420877.

- ^ "Haifa thesis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- The Syriac Maronites

- Syriac Maronite identity in Lebanon