Maajid Nawaz

Maajid Nawaz | |

|---|---|

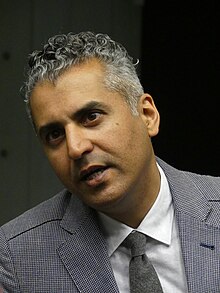

Nawaz in October 2018 | |

| Born | Maajid Usman Nawaz 2 November 1977 Southend-on-Sea, England |

| Occupation | Author · Founder of Quilliam |

| Education | SOAS, University of London (BA) London School of Economics (MSc) |

| Genre | Nonfiction |

| Subject | Islamism · Liberalism |

| Notable works | Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism On Blasphemy Islam and the Future of Tolerance |

| Spouse | Fellow activist

(m. 1999; div. 2008)Rachel Maggart (m. 2014) |

| Children | 2 |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Maajid Usman Nawaz (Urdu: [ˈmaːdʒɪd̪ nəwaːz]; born 2 November 1977)[1] is a British activist and former radio presenter. He was the founding chairman of the think tank Quilliam. Until January 2022, he was the host of an LBC radio show on Saturdays and Sundays. Born in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, to a British Pakistani family, Nawaz is a former member of the Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir. His membership led to his December 2001 arrest in Egypt, where he remained imprisoned until 2006. While there, he read books about human rights and made contact with Amnesty International who adopted him as a prisoner of conscience. He left Hizb-ut-Tahrir in 2007, renounced his Islamist past, and called for a secular Islam. Later, Nawaz co-founded Quilliam with former Islamists, including Ed Husain.[2]

In 2012, Nawaz published an autobiography, Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism, and has since become a prominent critic of Islamism in the United Kingdom. His second book, Islam and the Future of Tolerance (2015), co-authored with atheist author Sam Harris, was published in October 2015. He was the Liberal Democrats parliamentary candidate for London's Hampstead and Kilburn constituency in the 2015 United Kingdom general election.[3] Since 2020, Nawaz has been accused of promoting false claims and conspiracy theories related to COVID-19 and the 2020 United States presidential election.[4][5][6]

Early life and education

Nawaz was born in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, to parents of Pakistani origin.[7] His mother, Abi, moved to Southend with her family when she was nine. His father, Mo, is an electrical engineer who had worked for the Pakistan Navy but had to leave on medical grounds after he contracted tuberculosis.[8] After moving to the United Kingdom, Nawaz's father worked for an oil company in Libya, and moved between Libya and the United Kingdom until his retirement. Nawaz has an elder brother and a younger sister. In his memoir Radical, he uses the pseudonym Osman to refer to his brother.[8]

Nawaz was educated at Westcliff High School for Boys, a grammar school in Westcliff-on-Sea, a suburb of Southend.[9] Later, he studied law and Arabic at SOAS, University of London, and earned his master's degree in political theory from the London School of Economics.[10]

Islamist activism

Association with Hizb ut-Tahrir

Nawaz says that racism from classmates, Combat 18 gangs, and police, and feeling divided between his Pakistani and British heritage, meant he struggled to find his own identity growing up.[2][11][12] His elder brother, referred to pseudonymously as Osman, was recruited into Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT) by Nasim Ghani, who would later become the British leader of Hizb ut-Tahrir. Osman subsequently persuaded Nawaz to attend HT meetings held in Southend homes.[13] At those meetings, recruits were shown videos of Bosnian Muslims being massacred.[14] Watching these videos eventually resulted in Nawaz's formal recruitment in the HT.[11]

While a student at Newham College and then at SOAS, Nawaz quickly rose through the ranks. By the age of 17, he was recruiting students from Cambridge University, and by 19 he was on the national leadership of HT in the United Kingdom.[15] He became a national speaker and an international recruiter for Hizb ut-Tahrir, travelling to Pakistan and Denmark to further the party's ideology and set up organisational clandestine cells.[11]

Imprisonment in Egypt

As part of his bachelor's degree in law and Arabic, Nawaz spent a compulsory year abroad in Egypt, arriving just one day before the 9/11 attacks took place.[16][17] Since political Islamist organisations like Hizb ut-Tahrir were banned in Egypt, Nawaz was arrested and interrogated in Alexandria by the Egyptian security agency Aman al-Dawlah. Like most foreign prisoners, he was not subjected to torture but faced the threat of torture during interrogation and witnessed other prisoners being tortured.[11][18] He was then transferred to Tora Prison and put on trial. Represented by Sadiq Khan, he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment.[19][20] During the trial, he was adopted by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience,[11][21][22] and this helped him to secure his return to London.[23]

Disenchantment and exit from Hizb ut-Tahrir

While imprisoned in Tora Prison, Nawaz came across a wide spectrum of Muslims with varying ideological leanings, including jihadists, Islamists, Islamic scholars, and liberal Muslims.[24] Among the jihadists were the members of the terrorist organisation al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, and the assassins of former Egyptian president Anwar Sadat.[24] He met Islamist Essam el-Erian, the spokesman of the Muslim Brotherhood,[25] and Mohammed Badie, who in his youth had smuggled the manuscripts of Syed Qutb's Islamist manual Milestones out of prison, and had it published.[12][24]

Among the Islamic scholars, Nawaz continued his studies sitting with graduates of Cairo's Al-Azhar University and Dar al-'Ulum.[26] He specialised in the Arabic language whilst studying historical Muslim scholastics, sources of Islamic jurisprudence, Hadith historiography, and the art of Qur'anic recitation. He also committed half of the Qur'an to memory.[27] On the liberal end of the spectrum, he befriended author and sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim. He also benefited from the company of imprisoned Egyptian politician Ayman Nour, who was the head of the centrist and liberal Tomorrow Party and a runner-up to the 2005 Egyptian presidential election.[28][29] By 2007, Nawaz had renounced his Islamist past and called for a secular Islam.[30] In an interview with American broadcaster National Public Radio, Nawaz explained how, other than the interactions in prison, George Orwell's novel Animal Farm played a major role in his turnaround.[12]

Counter-extremist activism

| Part of a series on |

| Criticism of Islamism |

|---|

After completing his prison term in Egypt, Nawaz returned to the United Kingdom in 2006. In 2007, he resigned from Hizb-ut-Tahrir and resumed his bachelor's degree at SOAS.[31][32] He then founded the Quilliam Foundation, a counter-extremism think tank. He addressed the United States Committee on Homeland Security on the subject of Islamist extremism.[33] He also spoke at the Sovereign Challenge conference organised by United States Special Operations Command where he advocated the need to move beyond hard power, and look at new counter-radicalisation strategies.[34]

Nawaz played a major role in Tommy Robinson's exit from the far-right English Defence League (EDL), of which Robinson was the founder. He met Robinson in 2013 during the filming of a BBC documentary When Tommy met Mo, and subsequently met the EDL's co-leader, Kevin Carroll. Nawaz's personal story of turning back from Islamist extremism, and his counter-extremism work at Quilliam Foundation, encouraged Robinson and Carroll to quit the EDL.[35] Later, Robinson also apologised to Muslims for the fear caused by his EDL activism.[36] The move was hailed by Quilliam as "a huge success in community relations in the United Kingdom", and a continuation of combating all kinds of extremism, including Islamism and neo-Nazism.[37]

In July 2012, Nawaz published his autobiography, Radical. The Quilliam Foundation Ltd was put into liquidation on 9 April 2021.[38]

Activities in Pakistan

Nawaz has co-founded an activist group in Pakistan, named Khudi, which aims to combat extremism.[39] In 2009, with a BBC Newsnight crew and security team, Nawaz embarked on a counter-extremism tour, speaking at over 22 universities, and recruiting students all over Pakistan.[40]

Liberal Democrats

Nawaz was selected in July 2013 to stand as the Liberal Democrats candidate for the marginal north London constituency of Hampstead and Kilburn, in which he came third.[41] With the delegation of Liberal Democrat Friends of Israel he visited both sides of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[42]

In September 2013, Nawaz and his Camden District team was given the Dadabhai Naoroji Award for support and promotion of BAME (Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups) party members.[43] The award was presented by then-party president Tim Farron. In the same year, he was included in The Daily Telegraph's list of 50 most influential Liberal Democrats.[44]

In 2014, Nawaz received death threats after tweeting a Jesus and Mo cartoon alluding to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[45] Nawaz decided to tweet the cartoon after a BBC programme censored two audience members' shirts displaying cartoons of Muhammad.[46] Respect Party politician George Galloway called on Muslims, via a tweet, not to vote for the Liberal Democrats while Nawaz is one of their candidates.[45][47] By 24 January, a petition to the Liberal Democrats leader Nick Clegg demanding that Nawaz should be removed as a parliamentary candidate for the party had received 20,000 signatures.[46] Petition organisers denied a connection to its alleged originator, the Liberal Democrats member Mohammed Shafiq, and condemned the incitement to murder.[48] On 26 January, Clegg defended Nawaz's right to free expression and said that the death threats were not acceptable.[48]

On 2 July 2020, Nawaz announced his resignation from the Liberal Democrats.[49]

Radio show on LBC

From September 2016 to January 2022, Nawaz hosted an LBC radio show on Saturday and Sunday afternoons.[50][51] On 7 January 2022, LBC announced on Twitter that Nawaz would no longer present at LBC, effective immediately.[51] His firing came weeks after fellow host Iain Dale accused him of spreading ‘deranged rubbish’ concerning coronavirus vaccines. Mr Nawaz wrote that mass vaccination during a pandemic with a jab not tested for long-term side-effects “could be doing more harm than good”,[52] In response, he told his Twitter followers to subscribe to his Substack, telling them the show was his family's "only source of income".[53]

Claim by Southern Poverty Law Center

In October 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center in the United States accused Nawaz of being an "anti-Muslim extremist",[54] for which it was subsequently criticised by various media outlets,[55] including The Atlantic,[56] The Spectator,[57] and The Wall Street Journal,[58] and Nawaz himself.[59] The Lantos Foundation for Human Rights & Justice wrote a public letter to the SPLC urging it to retract the listing.[60] Nawaz announced his intention to file a defamation lawsuit against the SPLC on the 23 June 2017 episode of Real Time with Bill Maher.[61] The SPLC deleted the HTML version of its list in April 2018.[62]

In June 2018, the SPLC apologised and paid $3.375 million to Nawaz and Quilliam "to fund their work to fight anti-Muslim bigotry and extremism".[63][64] As part of the settlement, the then SPLC president J. Richard Cohen made a video apology,[65] and released a statement of apology to Nawaz and the Quilliam Foundation.[66] The agreement stipulated that the SPLC's apology was to be prominently displayed on various pages on their website, as well as distributed to every email address and mailing address on the SPLC mailing list.[67]

Views

Political commentary

Nawaz has criticised what he terms as the regressive left, which he describes as left-leaning people who—in his opinion—pander to Islamism, which he defines as a "global totalitarian theo-political project" with a "desire to impose any given interpretation of Islam over society as law".[68] He has also used the term control left, which he argues is the left-wing equivalent to the alt-right, to describe groups or individuals who he says support "post factual behaviour, violence being seen as an option and prioritising group identity over individual rights" and "they want to control our lives, control what we think, control how we even feel."[69]

Nawaz has been critical of multiculturalism, and he criticises what he describes as the failed 1990s policies on multiculturalism in Britain and Europe. He has argued that multiculturalism has failed ethnic minorities by not promoting integration, inhibiting social mobility in employment and gender inequality in Muslim communities, and has encouraged bigotry of low expectations. Nawaz has instead argued in favour of what he terms omniculturalism and integration, stating that both are more culturally and economically beneficial to minority communities.[70]

British and European politics

Nawaz voted Remain and was opposed to Brexit during the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum. Following the referendum, he argued that other Remain supporters needed to accept the result and that the outcome was "not all good news, but it's also not all bad news." Nawaz opined that Brexit could enable the country to participate in a CANZUK agreement and forge an era of new alliances to counter the influence of China on the West.[71] Nawaz maintained that while he is pro-immigration and supports accepting refugees, he also opined that the open border policy pursued by German chancellor Angela Merkel was a mistake in terms of national security, social integration, and fueling support for the far-right in Europe, and it had contributed to the Brexit result.[72] Nawaz opposes Scottish independence. In a 2020 article for UnHerd, he described the Scottish National Party as presenting a progressive image but using xenophobic sentiments. He also accused the party of "whitewashing" history over British colonialism to make Scotland appear as if it was colonised by England and played no role in the building of the British Empire.[73]

Nawaz has expressed opposition to demolishing statues and references to British historical figures in public spaces over past historical comments. In 2018, he criticised students from his alma-mater, SOAS University of London, who protested against a Winston Churchill themed café in London. He argued that while Churchill may have expressed controversial opinions, they should not be judged by modern standards, and said that "if we can't celebrate him, who can we celebrate?"[74] In response to the Black Lives Matter protests in the United Kingdom in which statues of historical figures were pulled over, Nawaz expressed agreement with the communities secretary Robert Jenrick that "community consultation" should be adopted as to whether the statues remain. He argued that the removal of statues "shouldn't be done unilaterally and it certainly shouldn't be done by the mob."[75]

American politics

Nawaz criticised Donald Trump over his proposal for a temporary ban on entry of Muslims into the United States during his 2016 presidential campaign. Following Trump's victory in the 2016 United States presidential election, Nawaz argued that the result came in part because of the left's failure to acknowledge white working-class voters who are statistically underrepresented in universities or employment. He stated that "Trump won because the hard left has abandoned the facts almost as quickly as the hard right."[76] After Trump assumed the presidency, Nawaz praised elements of the administration's policies, including attempts to negotiate peace talks with Kim Jong Un and attempts to sort out financial issues in NATO. He said that American liberals had been hypocritical in their criticisms of Trump compared to previous presidents.[77] After the 2020 United States presidential election, Nawaz argued that the public should "evaluate the policies and not the personality" when discussing Trump's legacy.[78] Nawaz views the 2020 election result as rigged, and has said that the January 6 United States Capitol attack was organised by anti-fascist organisations rather than supporters of Trump.[4]

Following the murder of George Floyd, Nawaz expressed support for peaceful demonstrations against racism, drawing upon his own experiences of racial prejudice growing up. He argued against using violent tactics.[79] He blamed rioting and damage to businesses on the "uniformed, masked, majority-white, far-left", and "spoiled-brat, privileged, gentrifying, Antifa-clad, anarchist rioters." He argued that violence and damage caused by white rioters would lead to over-policing of black neighborhoods.[80]

Security and human rights

Nawaz has opposed racial profiling of Muslims, extrajudicial detention of terror suspects, torture, targeted killings, and drone strikes.[81][82] He also opposed the Terrorism Act 2000, under which he was himself once detained, and called for the universal right to legal representation and right to silence in all cases and for all suspects.[83] In a talk given at George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, he suggested a revisit of the British government's historical approach to dealing with terrorism, and called for a more nuanced response to tackling the ideology of Islamism without breaching fundamental liberties of citizens.[84] According to him, security should never debase citizens of their civil liberties.[83]

In 2009, Nawaz was among the twelve advisers to British government who wrote an open letter to the then prime minister Gordon Brown asking him to hold Israel accountable for its attacks on the Gaza Strip.[85] He opposes Hamas, which he considers a terrorist organisation.[86] Nawaz has expressed support for Israel in his commentary, and criticised those who he says use anti-Zionism to promote antisemitic beliefs. He has also opined that opposition to Israel is "the mother of all virtue-signals". In 2018, he was shortlisted as a contender for the Times of Israel "communal ally of the year" of non-Jews "who has used their voice to fight anti-Semitism or delegitimization of Israel or has simply supported the community in the media, in politics or elsewhere over the last two years."[87]

In the aftermath of the 2015 San Bernardino attack, during which a debate about profiling occurred, Nawaz said that racial or religious profiling was a "terrible measure" that "does not prevent terrorism".[88]

Jihadism and the Islamic State

"It's not Islamophobic to scrutinise Islam just as it's not Christianophobic to scrutinise Christianity."

In 2015, Nawaz popularised the term Voldemort effect which pertained to analysts being fearful to call out the ideology of Islamism as the underlying cause of Jihadist terrorism.[90]

In a 2017 essay for The Wall Street Journal, Nawaz stated that jihadists of all types seek to create discord by "pitting Muslims against non-Muslims in the West and Sunni Muslims against Shiite Muslims in the East".[91] He argues that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) is out to provoke a Clash of Civilisations, which can be avoided by calling out the underlying Islamist ideology and isolating jihadists from ordinary Muslims.[91] He also took exception to Pope Francis's characterisation of the November 2015 Paris attacks as the start of a World War 3; he said that it is not another world war but a global jihadist insurgency.[91]

According to Nawaz, an insurgency is different from a conventional war in that insurgents rely on some level of support from the communities they recruit from. Since it is an insurgency, the counter-insurgency strategy should have messaging and psychological warfare as its critical parts, with the aim of isolating insurgents from their target host communities.[91] On a physical level, he supported the idea of an international coalition against ISIL, fronted by Sunni Arab forces and backed by international special forces.[91]

Nationalism and far-right movements

In a 2015 CNN interview, Nawaz condemned Donald Trump's remarks about his proposal to ban Muslims from entering the United States.[92] He said that when leaders pump up their followers by promising them utopian visions, and then fail to deliver on those promises, followers take matters into their own hands. He expressed his concern that disappointed followers of Trump would "end up joining fascist or far-right groups" and take matters into their own hands against the eight million Muslims in the United States".[93]

China's treatment of Uighurs

In July 2020, Nawaz began a hunger strike to protest against China's imprisonment and alleged atrocities, of the Uyghurs in the country, and to urge the government, through the UK Parliament petitions website, to impose sanctions on China over its treatment of Uyghur Muslims.[94][95] Nawaz said the abuses amounted to genocide and that it "leaves no room for neutrality".[96] Within a week, the petition passed the 100,000 signature threshold, thereby ensuring that a debate on the issue would take place in Parliament.[97]

COVID-19

In January 2021, Nawaz signed an open letter to the FBI and other Western intelligence agencies asking them to investigate the possibility that COVID-19 lockdowns were a "global fraud" promulgated by the Chinese Communist Party and intended to "impoverish the nations" that implemented them.[98][99] He has shared his mistrust of COVID-19 vaccines.[4][100] Nawaz said that he believed "natural immunity" was safer, and in a deleted tweet from January 2022 linking to a news story about mandatory vaccinations for COVID-19 in Italy, Nawaz captioned the story as "a global palace coup that suspends our rights ... by a network of fascists who seek a New World Order".[4][101]

Personal life

At the age of 21, Nawaz married a then fellow Hizb ut-Tahrir activist who was a biology student;[11] they have a son.[8][102] On Nawaz's decision to leave Hizb ut-Tahrir, they separated and later divorced.[103]

In 2014, Nawaz married Rachel Maggart, an artist and writer from the United States who works for an art gallery in London.[104][105] In 2017, Nawaz and Maggart had their first child.[106]

In February 2019, Nawaz said that he was assaulted in a racially-motivated attack by a white man.[107]

Books

- Nawaz, Maajid (2012). Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism. WH Allen. ISBN 978-0-7535-4077-0.

- Nawaz, Maajid; Harris, Sam (2015). Islam and the Future of Tolerance. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-08870-2.

See also

References

- ^ "The Quilliam Foundation Ltd. – Annual Return" (PDF). BizDb. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ a b Nawaz, Maajid (26 February 2015). "I was radicalised. So I understand how extremists exploit grievances". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "UK vote could create cross-border dynasty". Al Jazeera. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d Pellegrino, Silvia (13 July 2022). "What happened to Maajid Nawaz? Where the ex-LBC host went next". Press Gazette. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Nick Cohen (4 August 2022). "How Maajid Nawaz went from hero to conspiracy theorist". The JC.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz got Covid-19 facts wrong on the Joe Rogan podcast". Full Fact. 25 February 2022.

- ^ Shariatmadari, David. "Maajid Nawaz: how a former Islamist became David Cameron's anti-extremism adviser". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b c Nawaz (2012): pp. 20–30.

- ^ Sexton, Christine (25 June 2009). "Ex-extremist: My message of peace to the Islamic world". Southend Standard. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Lib Dem Profile of Maajid Nawaz". Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f "News". Women-Without-Borders. 12 April 2008. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b c "How Orwell's 'Animal Farm' Led A Radical Muslim To Moderation". NPR.org. NPR. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): pp. 80–91.

- ^ Driscoll, Margaret. "Maajid Nawaz: And most other jihadists are just like me too". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "A Global Culture to Fight Radicalization". TED.com. 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Talk: From Islamism to Secular Liberalism: Socrateslezing". YouTube. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ Casciani, Dominic (3 March 2006). "UK | Freed Britons attack government". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): p. 241.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): p. 257.

- ^ "Egypt trial Britons' case resumes". news.bbc.co.uk. 21 December 2002. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): pp. 250–257.

- ^ "Amnesty International – Library – Egypt: Opening of trial of three Britons and 23 Egyptians raises unfair trial and torture concerns". Mafhoum.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Thomas Chatterton Williams (28 March 2017). "Can a Former Islamist Make It Cool to Be Moderate?". New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Nawaz (2012): pp. 262–263.

- ^ "Democracy is our revenge". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): pp. 285–286.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): p. 287.

- ^ "Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism". The Christian Science Monitor. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz: The Repentant Radical". Newsweek. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Morris, Nigel (19 July 2013). "Former Islamist Maajid Nawaz to fight marginal parliamentary seat for Lib Dems in 2015 election". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): pp. 323–325.

- ^ Nawaz (2012): p. 331.

- ^ "Events". Washingtoninstitute.org. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "[PDF]: US Special Operations command Conference" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ Malik, Shiv (11 October 2013). "Ex-EDL leader Tommy Robinson says sorry for causing fear to Muslims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (8 October 2013). "Tommy Robinson quits EDL saying it has become 'too extreme'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "EDL: Tommy Robinson and deputy Kevin Carroll quit far right group". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "The Quilliam Foundation Ltd". Companies House. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Charlotte Higgins (12 August 2012). "Reformed Islamist extremist spreads virtues of democracy through Pakistan". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Former Islamist takes on Pakistan extremism". 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Osley, Richard (25 July 2013). "Lib Dems hope Maajid Nawaz can boost their election hopes in Hampstead and Kilburn". Camden New Journal. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Lipman, Jennifer (28 June 2012). "Ex-radical speaks with suicide bomb victim's father". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "LibDem Party Awards 2013: The Winners". Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Top 50 most influential Liberal Democrats: 26–50". The Daily Telegraph. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ a b Keith Perry "Lib Dem candidate receives death threats for tweeting Prophet Mohammed cartoon" Archived 25 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Daily Telegraph 21 January 2014

- ^ a b Nick Cohen "The Liberal Democrats face a true test of liberty" Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Observer, 25 January 2014

- ^ Jessica Elgot "George Galloway And Muslim Activists Round On Lib Dem Candidate Maajid Nawaz" Archived 23 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Huffington Post, 21 January 2014

- ^ a b Jonathan Brown and Ian Johnston "Nick Clegg attacks death threats against Maajid Nawaz – Lib Dem candidate who tweeted a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed and Jesus greeting each other" Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 26 January 2014

- ^ Majiid Nawaz [@MaajidNawaz] (3 July 2020). "I hereby announce my resignation from @LibDems. I'm gearing up for a battle bigger than politics. From now on I endorse all parties, not one. I personally endorse @sajidjavid as Tory leader. @Keir_Starmer as Labour leader & @LaylaMoran as new leader for @LibDems #Solidarity" (Tweet). Retrieved 15 July 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz joins LBC for weekend shows". RadioToday. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Presenter Maajid Nawaz has left LBC with immediate effect". RadioToday. 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "LBC presenter Maajid Nawaz says 'I refuse to go quietly' as show to end". Independent.co.uk. 7 January 2022.

- ^ Maher, Bron (7 January 2022). "Presenter Maajid Nawaz leaves LBC after backlash to controversial tweets". Press Gazette. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Field Guide to Anti-Muslim Extremists" (PDF). Splcenter. Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ Walsh, Michael (31 October 2016). "SPLC receives backlash after placing activist Maajid Nawaz on 'anti-Muslim extremist' list". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ Graham, David A. (29 October 2016). "How Did Maajid Nawaz End Up on a List of 'Anti-Muslim Extremists'?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Nick (31 October 2016). "The white left has issued its first fatwa". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ "Branding Moderates as 'Anti-Muslim'". Wall Street Journal. 30 October 2016. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (29 October 2016). "I'm A Muslim Reformer. Why Am I Being Smeared as an 'Anti-Muslim Extremist'?". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "Lantos Foundation Calls Out Southern Poverty Law Center". Lantos Foundation. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Muslim Anti-Extremist Maajid Nawaz on Maher; Talks Lawsuit Against Southern Poverty Law Center". RealClearPolitics.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Crowe, Jack (19 April 2018). "Southern Poverty Law Center Quietly Deleted List of 'Anti-Muslim' Extremists After Legal Threat". National Review. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ "Statement regarding Maajid Nawaz and Quilliam Foundation". SPLCenter.org. SPLC. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ Matt Naham (18 June 2018). "Southern Poverty Law Center Must Pay $3.3 Million After Falsely Naming Anti-Muslim Extremists". Law & Crime. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Quilliam International (18 June 2018). "Richard Cohen SPLC President Apologising to Maajid Nawaz and Quilliam". Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Richardson, Valerie (18 June 2018). "Southern Poverty pays $3.3M to Quilliam, Nawaz for labeling them 'anti-Muslim extremists'". AP News. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

The apology reads as follows: 'The Southern Poverty Law Center was wrong to include Maajid Nawaz and the Quilliam Foundation in our Field Guide to Anti-Muslim Extremists. Since we published the Field Guide, we have taken the time to do more research and have consulted with human rights advocates we respect. We've found that Mr. Nawaz and Quilliam have made valuable and important contributions to public discourse, including by promoting pluralism and condemning both anti-Muslim bigotry and Islamist extremism. Although we may have our differences with some of the positions that Mr. Nawaz and Quilliam have taken, they are most certainly not anti-Muslim extremists. We would like to extend our sincerest apologies to Mr. Nawaz, Quilliam, and our readers for the error, and we wish Mr. Nawaz and Quilliam all the best.'

- ^ "SPLC Final Executed Settlement Agreement" (PDF). 18 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (2012). Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism. WH Allen. ISBN 9781448131617.

- ^ "Maajid: The Left is No Longer Liberal".

- ^ "Maajid Says Multiculturalism is Dead".

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz explains how UK can prosper post-Brexit: 'It's not all bad news'". LBC. 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Merkel's 'Open Door' Policy Helped Lead To Brexit, Says Maajid Nawaz". LBC. 16 July 2017.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (24 May 2020). "The racism lurking behind Scottish nationalism". UnHerd.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (1 February 2018). "'Churchill was flawed like all the greats but his achievements outshine his shortcomings'". Sky News.

- ^ "'All stakeholders in society' should be involved in statues debate, Maajid Nawaz insists". LBC. 17 January 2021.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (9 November 2016). "The fear that propelled Donald Trump requires no logic". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Maajid Nawaz: Give Trump some credit on YouTube

- ^ "Massive rise in support for Trump cannot be ignored, Maajid Nawaz says". LBC. 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz's moving plea to demonstrators to remain peaceful". LBC. 31 May 2020.

- ^ Salim, Eman (31 May 2020). "White-bourgeois Antifa rioters are burning black minority neighborhoods – Maajid rages". The Union Journal.

- ^ "US drone killing of Anwar al-Awlaki reinforces terrorists". TheGuardian.com. October 2011. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Racial Profiling: Maajid Nawaz debates MP Khalid Mehmood". YouTube. 19 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Maajid Nawaz speaks out against Schedule 7 terror laws at Liberal Democrats Conference". Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz moderates discussion on Violent Extremism in Europe". Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Guardia Letter: Advisor to Gordon Brown". TheGuardian.com. 8 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (24 July 2014). "OPINION: Palestine must be free ... from Hamas". Jewish News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

- ^ Philpot, Robert (19 February 2018). "The British activist who went from radical Islam to staunch Israel ally". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Nawaz, Maajid (7 December 2015). "Why ISIS Just Loves Profiling". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Being offended by cartoons discussed on #BBCTBQ". Skeptical-science.com. 11 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Maajid Nawaz. "We Treat Radical Islam Like Voldemort — That's Bad for a Very Counterintuitive Reason". Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Nawaz, Maajid (11 December 2015). "How to beat Islamic State". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "Donald Trump is radicalizing his followers: Terrorism expert explains how Trump is marching Americans towards extremism". Salon. 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Video: Terrorists don't have a profile". CNN. 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz goes on hunger strike to support Uyghurs". 5 Pillars. 18 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz is on hunger strike to stop Uighur Muslim genocide" (Press release). London: Quilliam International. 17 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ ""Genocide leaves no room for neutrality": Public must be vocal against Uighur atrocities". LBC.

- ^ "Parliament set to debate China's persecution of Uighur Muslims". National Secular Society. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (31 January 2021). "LBC's Maajid Nawaz's fascination with conspiracies raises alarm". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Senger & others (10 January 2021). "The Chinese Communist Party's Global Lockdown Fraud". medium.com. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Dale, Daniel (11 September 2021). "Fact-checking the false but viral story about F-22 pilots resigning after a vaccination text from the secretary of defense | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Gregory, Andy (7 January 2022). "LBC presenter Maajid Nawaz says 'I refuse to go quietly' after station announces his departure". The Independent. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Moore, Charles (30 July 2012). "An insider's exposé of Islamist extremism". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- ^ Landesman, Cosmo (1 September 2013). "Maajid Nawaz: a tortured jihadist blossoms into Clegg's darling". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "Rachel Maggart Info". Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ For the date, see "1:40 PM". Twitter. 19 October 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2015. For the name, see "6:26 PM". Twitter. 12 April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Maajid Nawaz". www.facebook.com.

- ^ "Radio host hit in face in 'racist attack'". BBC News. 19 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

Further reading

- Baran, Zeyno (2011). The Pakistan Cauldron: Conspiracy, Assassination & Instability. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-1248-4.

- Farwell, James P. (2011). Citizen Islam: The Future of Muslim Integration in the West. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59797-982-5.

- Kazemipur, Abdolmohammad (2014). The Muslim Question in Canada: A Story of Segmented Integration. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2731-7.

- Garbaye, Romain; Schnapper, Pauline (2014). The Politics of Ethnic Diversity in the British Isles. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-35154-8.

External links

- 1977 births

- 21st-century British essayists

- 21st-century English memoirists

- Alumni of SOAS University of London

- Alumni of the London School of Economics

- Amnesty International prisoners of conscience held by Egypt

- British writers in Arabic

- BBC radio presenters

- British civil rights activists

- British foreign policy writers

- British people imprisoned abroad

- British critics of religions

- British special advisers

- Critics of Islamism

- Critics of multiculturalism

- Democracy activists

- English anti–Iraq War activists

- English columnists

- English essayists

- English human rights activists

- English Muslims

- English non-fiction writers

- English people of Pakistani descent

- Former members of Hizb ut-Tahrir

- LBC radio presenters

- Liberal Democrats (UK) parliamentary candidates

- Living people

- Muslim reformers

- People from Southend-on-Sea