Little Hagia Sophia

| Little Hagia Sophia Mosque Küçük Ayasofya Camii | |

|---|---|

Northeast (rear) view of Little Hagia Sophia in 2013 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Year consecrated | between 1506 and 1513 |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°00′10″N 28°58′19″E / 41.00278°N 28.97194°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Isidorus of Miletus, Anthemius of Tralles |

| Type | church |

| Style | Byzantine |

| Groundbreaking | 527 |

| Completed | 536 |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Materials | brick, granite, marble |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

Little Hagia Sophia Mosque (Template:Lang-tr), formerly the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus (Template:Lang-el, Ekklēsía tôn Hagíōn Sergíou kaì Bákchou en toîs Hormísdou), is a former Greek Eastern Orthodox church dedicated to Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople, converted into a mosque during the Ottoman Empire.

This Byzantine building with a central dome plan was erected in the sixth century by Justinian, likely was a model for Hagia Sophia ("Holy Wisdom"), and is one of the most important early Byzantine buildings in Istanbul. It was recognized at the time as an adornment to the entire city,[1] and a modern historian of the East Roman Empire has written that the church, "by the originality of its architecture and the sumptuousness of its carved decoration, ranks in Constantinople second only to St. Sophia itself".[2]

Location

The building stands in Istanbul, in the district of Fatih and in the neighborhood of Kumkapı, at a short distance from the Marmara Sea, near the ruins of the Great Palace and to the south of the Hippodrome. It is now separated from the sea by the Sirkeci-Halkalı suburban railway line and the coastal road, Kennedy Avenue.

History

Byzantine period

According to later legend, during the reign of Justin I, his nephew Justinian had been accused of plotting against the throne and was sentenced to death, avoided after Saints Sergius and Bacchus appeared before Justin and vouched for Justinian’s innocence. He was freed and restored to his title of Caesar, and in gratitude vowed that he would dedicate a church to the saints once he became emperor. The construction of this Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, between 527 and 536 AD (only a short time before the erection of the Hagia Sophia between 532 and 537), was one of the first acts of the reign of Justinian I.[3]

The new church lay at the border between the First and Τhird Regio of the City,[4] in an irregular area between the Palace of Hormisdas (the house of Justinian before his accession to the throne) and the Church of the Saints Peter and Paul. Back then, the two churches shared the same narthex, atrium and propylaea. The new church became the center of the complex, and part still survives today, towards the south of the northern wall of one of the two other edifices. The church was one of the most important religious structures in Constantinople. Shortly after the building of the church a monastery bearing the same name was built near the edifice.

Construction of the new church began shortly before that of Hagia Sophia, built from 532 to 537. It was believed that the building had been designed by the same architects, Isidorus of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, as a kind of "dress rehearsal" for that of the largest church of the Byzantine Empire. However, the building is quite different in architectural detail from the Hagia Sophia and the notion that it was but a small-scale version has largely been discredited.[3]

During the years 536 and 537, the Palace of Hormisdas became a Monophysite monastery, where followers of that sect, coming from the eastern regions of the Empire and escaping the persecutions against them, found protection by Empress Theodora.[5]

In year 551 Pope Vigilius, who some years before had been summoned to Constantinople by Justinian, found refuge in the church from the soldiers of the Emperor who wanted to capture him, and this attempt caused riots.[5] During the Iconoclastic period the monastery became one of the centers of this movement in the City.

Ottoman period

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the church remained untouched until the reign of Bayezid II. Then (between 1506 and 1513) it was transformed into a mosque by Hüseyin Ağa, the Chief Black Eunuch, custodian of the Bab-ı-Saadet (literally The Gate of Felicity in Ottoman Turkish) in the Sultan's residence, the Topkapı Palace. At that time the portico and madrasah were added to the church.[6]

In 1740 the Grand Vizier Hacı Ahmet Paşa restored the mosque and built the Şadırvan (fountain). Damage caused by the earthquakes of 1648 and 1763 was repaired in 1831 under the reign of Sultan Mahmud II. In 1762 the minaret was first built. It was demolished in 1940 and built again in 1956.[6]

The pace of decay of the building, which already suffered because of humidity and earthquakes through the centuries, accelerated after the construction of the railway. Parts of St. Peter and Paul to the south of the building were demolished to accommodate the rail line. Other damage was caused by the building's use as housing for the refugees during the Balkan Wars.[6]

Due to the increasing threats to the building's static integrity, it was added some years ago to the UNESCO watch list of endangered monuments. The World Monuments Fund added it to its Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in 2002, 2004, and 2006. After an extensive restoration which lasted several years and ended in September 2006, it has been opened again to the public and for worship.

Architecture

Exterior

The exterior masonry of the structure adopts the usual technique of that period in Constantinople, which uses bricks sunk in thick beds of mortar. The walls are reinforced by chains made of small stone blocks.

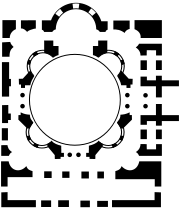

The building, the central plan of which was consciously repeated in the basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna and served as a model for the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan in the construction of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque, has the shape of an octagon inscribed in an irregular quadrilateral. It is surmounted by a beautiful umbrella dome in sixteen compartments with eight flat sections alternating with eight concave ones, standing on eight polygonal pillars.

The narthex lies on the west side, opposed to an antechoir.[7] Many effects in the building were later used in Hagia Sophia: the exedrae expand the central nave on diagonal axes, colorful columns screen the ambulatories from the nave, and light and shadow contrast deeply on the sculpture of capitals and entablature.[8]

In front of the building there is a portico (which replaced the atrium) and a court (both added during the Ottoman period), with a small garden, a fountain for the ablutions and several small shops.

Interior

Inside the edifice there is a beautiful two-storey colonnade which runs along the north, west and south sides, and bears an elegant inscription in twelve Greek hexameters dedicated to the Emperor Justinian, his wife, Theodora, and Saint Sergius, the patron-saint of the soldiers of the Roman army. For some unknown reason, Saint Bacchus is not mentioned. The columns are alternately of verd antique and red Synnada marble; the lower storey has 16, while the upper has 18. Many of the column capitals still bear the monograms of Justinian and Theodora.[9]

-

Column detail and northern part of the dome.

-

The dome.

-

The gallery.

-

Colonnades.

-

Interior north-west (1914).

Nothing remains of the original interior decoration of the church, which contemporary chroniclers describe as being covered in mosaics with walls of variegated marble. During the Ottoman conversion into a mosque, the windows and entrance were modified, floor level raised, and interior walls plastered.[8]

Grounds

North of the edifice there is a small Muslim cemetery with the türbe of Hüseyin Ağa, the founder of the mosque.

See also

External links

Notes

- ^ Procopius, De Aedificiis, I.4.3–8. Procopius was describing both the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus and the conjoined Church of Saints Peter and Paul.

- ^ Norwich (1988), p. 531

- ^ a b Freely (2000), p. 137

- ^ Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 177

- ^ a b Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 178

- ^ a b c Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 182

- ^ Antechoir is the part of the church in front of the Choir, often reserved for the clergy.

- ^ a b Mathews (1976), p. 242

- ^ Capitals of similar shape are also used in the church of Hagios Andreas en te Krisei, another sixth-century foundation in Constantinople. Van Millingen (1912), p. 115

Sources

- Bardill, Jonathon (2000). "The Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople and the Monophysite Refugees"[permanent dead link], extract from Dumbarton Oaks Papers No. 54. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Freely, John (2000). Blue Guide Istanbul. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32014-6.

- Krautheimer, Richard (1986). Architettura paleocristiana e bizantina (in Italian). Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-59261-0.

- Mango, Cyril (1975). Byzantine Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-1004-7.

- Mango, Cyril (1972). "The church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus at Constantinople and the alleged tradition of octagonal palatine churches". Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik (21). Vienna: 189–93.

- Mathews, Thomas F. (1976). The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01210-2.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon Zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Norwich, John Julius (1988). Byzantium: the early centuries. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-53778-5.

- Van Millingen, Alexander (1912). Byzantine Churches of Constantinople. London: MacMillan & Co.

Further reading

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 249, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries