Mississippi

Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): "The Magnolia State" and "The Hospitality State" | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: "One Mississippi" | |

Map of the United States with Mississippi highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Mississippi Territory (1798-1817) |

| Admitted to the Union | December 10, 1817 (20th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Jackson |

| Largest metro | Greater Jackson |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Tate Reeves (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Delbert Hosemann (R) |

| Legislature | Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Mississippi |

| U.S. senators | Roger Wicker (R) Cindy Hyde-Smith (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 1: Trent Kelly (R) 2: Bennie Thompson (D) 3: Michael Guest (R) 4: Mike Ezell (R) (list) |

| Area | |

• Total | 48,430 sq mi (125,443 km2) |

| • Land | 46,952 sq mi (121,607 km2) |

| • Water | 1,521 sq mi (3,940 km2) 3% |

| • Rank | 32nd |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 340 mi (545 km) |

| • Width | 170 mi (275 km) |

| Elevation | 300 ft (90 m) |

| Highest elevation | 807 ft (246.0 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2024) | |

• Total | |

| • Rank | 35th |

| • Density | 63.5/sq mi (24.5/km2) |

| • Rank | 33rd |

| • Median household income | $54,200 (2023)[4] |

| • Income rank | 50th |

| Demonym | Mississippian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | MS |

| ISO 3166 code | US-MS |

| Trad. abbreviation | Miss. |

| Latitude | 30°12′ N to 35° N |

| Longitude | 88°6′ W to 91°39′ W |

| Website | ms |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| Slogan | Virtute et armis (Latin) |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) |

| Butterfly | Spicebush swallowtail (Papilio troilus) |

| Fish | Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) |

| Flower | Magnolia |

| Insect | Western honey bee (Apis mellifera) |

| Mammal | White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) |

| Reptile | American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) |

| Tree | Southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Color(s) | red and blue |

| Dance | Square dance[5] |

| Food | Sweet potato |

| Gemstone | Emerald |

| Mineral | Gold |

| Rock | Granite |

| Shell | Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) |

| Toy | Teddy Bear[6] |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2002 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Mississippi (/ˌmɪsɪˈsɪpi/ ⓘ MISS-iss-IP-ee)[7] is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the southwest, and Arkansas to the northwest. Mississippi's western boundary is largely defined by the Mississippi River, or its historical course.[8] Mississippi is the 32nd largest by area and 35th-most populous of the 50 U.S. states and has the lowest per-capita income. Jackson is both the state's capital and largest city. Greater Jackson is the state's most populous metropolitan area, with a population of 591,978 in 2020. Other major cities include Gulfport, Southaven, Hattiesburg, Biloxi, Olive Branch, Tupelo, Meridian, and Greenville.[9]

The state's history traces back to around 9500 BC with the arrival of Paleo-Indians, evolving through periods marked by the development of agricultural societies, rise of the Mound Builders, and flourishing of the Mississippian culture. European exploration began with the Spanish in the 16th century, followed by French colonization in the 17th century. Mississippi's strategic location along the Mississippi River made it a site of significant economic and strategic importance, especially during the era of cotton plantation agriculture, which led to its wealth pre-Civil War, but entrenched slavery and racial segregation. On December 10, 1817, Mississippi became the 20th state admitted to the Union. By 1860, Mississippi was the nation's top cotton-producing state and slaves accounted for 55% of the state population.[10] Mississippi declared its secession from the Union on January 9, 1861, and was one of the seven original Confederate States, which constituted the largest slaveholding states in the nation. Following the Civil War, it was restored to the Union on February 23, 1870.[11] Mississippi's political and social landscape was dramatically shaped by the Civil War, Reconstruction era, and civil rights movement, with the state playing a pivotal role in the struggle for civil rights. From the end of the Civil War to the 1960s, Mississippi was dominated by socially conservative and segregationist Southern Democrats dedicated to upholding white supremacy.

Despite progress, Mississippi continues to grapple with challenges related to health, education, and economic development, often ranking among the lowest in the United States in national metrics for wealth, health care quality, and educational attainment.[12][13][14][15] Economically, it relies on agriculture, manufacturing, and an increasing focus on tourism, highlighted by its casinos and historical sites. Mississippi produces more than half of the country's farm-raised catfish, and is a top producer of sweet potatoes, cotton and pulpwood. Others include advanced manufacturing, utilities, transportation, and health services.[16] Mississippi is almost entirely within the east Gulf Coastal Plain, and generally consists of lowland plains and low hills. The northwest remainder of the state consists of the Mississippi Delta. Mississippi's highest point is Woodall Mountain at 807 feet (246 m) above sea level adjacent to the Cumberland Plateau; the lowest is the Gulf of Mexico. Mississippi has a humid subtropical climate classification.

Mississippi is known for its deep religious roots, which play a central role in its residents' lives. The state ranks among the highest of U.S. states in religiosity. Mississippi is also known for being the state with the highest proportion of African-American residents. The state's governance structure is based on the traditional separation of powers, with political trends showing a strong alignment with conservative values. Mississippi boasts a rich cultural heritage, especially in music, being the birthplace of the blues and contributing significantly to the development of the music of the United States as a whole.

Etymology

[edit]The state's name is derived from the Mississippi River, which flows along and defines its western boundary. European-American settlers named it after the Ojibwe word ᒥᓯ-ᓰᐱ misi-ziibi (English: great river).

History

[edit]This section should include only a brief summary of History of Mississippi. (April 2023) |

Near 9500 BC Native Americans or Paleo-Indians arrived in what today is referred to as the American South.[17] Paleo-Indians in the South were hunter-gatherers who pursued the megafauna that became extinct following the end of the Pleistocene age. In the Mississippi Delta, Native American settlements and agricultural fields were developed on the natural levees, higher ground in the proximity of rivers. The Native Americans developed extensive fields near their permanent villages. Together with other practices, they created some localized deforestation but did not alter the ecology of the Mississippi Delta as a whole.[18]

After thousands of years, succeeding cultures of the Woodland and Mississippian culture eras developed rich and complex agricultural societies, in which surplus supported the development of specialized trades. Both were mound builder cultures. Those of the Mississippian culture were the largest and most complex, constructed beginning about 950 AD. The peoples had a trading network spanning the continent from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. Their large earthworks, which expressed their cosmology of political and religious concepts, still stand throughout the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.

Descendant Native American tribes of the Mississippian culture in the Southeast include the Chickasaw and Choctaw. Other tribes who inhabited the territory of Mississippi (and whose names were honored by colonists in local towns) include the Natchez, the Yazoo, and the Biloxi.

The first major European expedition into the territory that became Mississippi was that of the Spanish explorer, Hernando de Soto, who passed through the northeast part of the state in 1540, in his second expedition to the New World.

Colonial era

[edit]In April 1699, French colonists established the first European settlement at Fort Maurepas (also known as Old Biloxi), built in the vicinity of present-day Ocean Springs on the Gulf Coast. It was settled by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville. In 1716, the French founded Natchez on the Mississippi River (as Fort Rosalie); it became the dominant town and trading post of the area. The French called the greater territory "New France"; the Spanish continued to claim part of the Gulf coast area (east of Mobile Bay) of present-day southern Alabama, in addition to the entire area of present-day Florida. The British assumed control of the French territory after the French and Indian War.

During the colonial era, European (chiefly French and Spanish) settlers imported enslaved Africans to work on cash crop plantations. Under French and Spanish rule, there developed a class of free people of color (gens de couleur libres), mostly multiracial descendants of European men and enslaved or free black women, and their mixed-race children. In the early days the French and Spanish colonists were chiefly men. Even as more European women joined the settlements, the men had interracial unions among women of African descent (and increasingly, multiracial descent), both before and after marriages to European women. Often the European men would help their multiracial children get educated or gain apprenticeships for trades, and sometimes they settled property on them; they often freed the mothers and their children if enslaved, as part of contracts of plaçage. With this social capital, the free people of color became artisans, and sometimes educated merchants and property owners, forming a third class between the Europeans and most enslaved Africans in the French and Spanish settlements, although not so large a free community as in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana.

After Great Britain's victory in the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War), the French surrendered the Mississippi area to them under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1763). They also ceded their areas to the north that were east of the Mississippi River, including the Illinois Country and Quebec. After the Peace of Paris (1783), the lower third of Mississippi came under Spanish rule as part of West Florida. In 1819 the United States completed the purchase of West Florida and all of East Florida in the Adams–Onís Treaty, and in 1822 both were merged into the Florida Territory.

United States territory

[edit]After the American Revolution (1775–83), Britain ceded this area to the new United States of America. The Mississippi Territory was organized on April 7, 1798, from territory ceded by Georgia and South Carolina to the United States. Their original colonial charters theoretically extended west to the Pacific Ocean. The Mississippi Territory was later twice expanded to include disputed territory claimed by both the United States and Spain.

From 1800 to about 1830, the United States purchased some lands (Treaty of Doak's Stand) from Native American tribes for new settlements of European Americans. The latter were mostly migrants from other Southern states, particularly Virginia and North Carolina, where soils were exhausted.[19] New settlers kept encroaching on Choctaw land, and they pressed the federal government to expel the Native Americans. On September 27, 1830, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed between the U.S. Government and the Choctaw. The Choctaw agreed to sell their traditional homelands in Mississippi and Alabama, for compensation and removal to reservations in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). This opened up land for sale to European-American migrant settlement.

Article 14 in the treaty allowed those Choctaw who chose to remain in the states to become U.S. citizens, as they were considered to be giving up their tribal membership. They were the second major Native American ethnic group to do so (some Cherokee were the first, who chose to stay in North Carolina and other areas during rather than join the removal).[20][21] Today their descendants include approximately 9,500 persons identifying as Choctaw, who live in Neshoba, Newton, Leake, and Jones counties. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians reorganized in the 20th century and is a Federally recognized tribe.

Many slaveholders brought enslaved African Americans with them or purchased them through the domestic slave trade, especially in New Orleans. Through the trade, an estimated nearly one million slaves were forcibly transported to the Deep South, including Mississippi, in an internal migration that broke up many slave families of the Upper South, where planters were selling excess slaves. The Southerners imposed slave laws in the Deep South and restricted the rights of free blacks.

Beginning in 1822, slaves in Mississippi were protected by law from cruel and unusual punishment by their owners.[22] The Southern slave codes made the willful killing of a slave illegal in most cases.[23] For example, the 1860 Mississippi case of Oliver v. State charged the defendant with murdering his own slave.[24]

Statehood to Civil War

[edit]Mississippi became the 20th state on December 10, 1817. David Holmes was the first governor.[25] The state was still occupied as ancestral land by several Native American tribes, including Choctaw, Natchez, Houma, Creek, and Chickasaw.[26][27]

Plantations were developed primarily along the major rivers, where the waterfront provided access to the major transportation routes. This is also where early towns developed, linked by the steamboats that carried commercial products and crops to markets. The remainder of Native American ancestral land remained largely undeveloped but was sold through treaties until 1826, when the Choctaws and Chickasaws refused to sell more land.[28] The combination of the Mississippi state legislature's abolition of Choctaw Tribal Government in 1829,[29] President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act and the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830,[30] the Choctaw were effectively forced to sell their land and were transported to Oklahoma Territory. The forced migration of the Choctaw, together with other southeastern tribes removed as a result of the Act, became known as the Trail of Tears.

When cotton was king during the 1850s, Mississippi plantation owners—especially those of the Delta and Black Belt central regions—became wealthy due to the high fertility of the soil, the high price of cotton on the international market, and free labor gained through their holding enslaved African Americans. They used some of their profits to buy more cotton land and more slaves. The planters' dependence on hundreds of thousands of slaves for labor and the severe wealth imbalances among whites, played strong roles both in state politics and in planters' support for secession. Mississippi was a slave society, with the economy dependent on slavery. The state was thinly settled, with population concentrated in the riverfront areas and towns.

By 1860, the enslaved African-American population numbered 436,631 or 55% of the state's total of 791,305 persons. Fewer than 1000 were free people of color.[31] The relatively low population of the state before the American Civil War reflected the fact that land and villages were developed only along the riverfronts, which formed the main transportation corridors. Ninety percent of the Delta bottomlands were still frontier and undeveloped.[32] The state needed many more settlers for development. The land further away from the rivers was cleared by freedmen and white migrants during Reconstruction and later.[32]

Civil War through late 19th century

[edit]

On January 9, 1861, Mississippi became the second state to declare its secession from the Union, and it was one of the founding members of the Confederate States. The first six states to secede were those with the highest number of slaves. During the war, Union and Confederate forces struggled for dominance on the Mississippi River, critical to supply routes and commerce. More than 80,000 Mississippians fought in the Civil War for the Confederate Army. Around 17,000 black and 545 white Mississippians would serve in the Union Army. Pockets of Unionism in Mississippi were in places such as the northeastern corner of the state and Jones County, where Newton Knight formed a revolt with Unionist leanings, known as the "Free State of Jones".[33] Union General Ulysses S. Grant's long siege of Vicksburg finally gained the Union control of the river in 1863.

In the postwar period, freedmen withdrew from white-run churches to set up independent congregations. The majority of blacks left the Southern Baptist Convention, sharply reducing its membership. They created independent black Baptist congregations. By 1895 they had established numerous black Baptist state associations and the National Baptist Convention of black churches.[34]

In addition, independent black denominations, such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church (established in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the early 19th century) and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (established in New York City), sent missionaries to the South in the postwar years. They quickly attracted hundreds of thousands of converts and founded new churches across the South. Southern congregations brought their own influences to those denominations as well.[34][35]

During Reconstruction, the first Mississippi constitutional convention in 1868, with delegates both black and white, framed a constitution whose major elements would be maintained for 22 years.[36] The convention was the first political organization in the state to include African-American representatives, 17 among the 100 members (32 counties had black majorities at the time). Some among the black delegates were freedmen, but others were educated free blacks who had migrated from the North. The convention adopted universal suffrage; did away with property qualifications for suffrage or for office, a change that also benefited both blacks and poor whites; provided for the state's first public school system; forbade race distinctions in the possession and inheritance of property; and prohibited limiting civil rights in travel.[36] Under the terms of Reconstruction, Mississippi was restored to the Union on February 23, 1870.

Because the Mississippi Delta contained so much fertile bottomland that had not been developed before the American Civil War, 90 percent of the land was still frontier. After the Civil War, tens of thousands of migrants were attracted to the area by higher wages offered by planters trying to develop land. In addition, black and white workers could earn money by clearing the land and selling timber, and eventually advance to ownership. The new farmers included many freedmen, who by the late 19th century achieved unusually high rates of land ownership in the Mississippi bottomlands. In the 1870s and 1880s, many black farmers succeeded in gaining land ownership.[32]

Around the start of the 20th century, two-thirds of the Mississippi farmers who owned land in the Delta were African American.[32] But many had become overextended with debt during the falling cotton prices of the difficult years of the late 19th century. Cotton prices fell throughout the decades following the Civil War. As another agricultural depression lowered cotton prices into the 1890s, numerous African-American farmers finally had to sell their land to pay off debts, thus losing the land which they had developed by hard, personal labor.[32]

Democrats had regained control of the state legislature in 1875, after a year of expanded violence against blacks and intimidation of whites in what was called the "white line" campaign, based on asserting white supremacy. Democratic whites were well armed and formed paramilitary organizations such as the Red Shirts to suppress black voting. From 1874 to the elections of 1875, they pressured whites to join the Democrats, and conducted violence against blacks in at least 15 known "riots" in cities around the state to intimidate blacks. They killed a total of 150 blacks, although other estimates place the death toll at twice as many. A total of three white Republicans and five white Democrats were reported killed. In rural areas, deaths of blacks could be covered up. Riots (better described as massacres of blacks) took place in Vicksburg, Clinton, Macon, and in their counties, as well-armed whites broke up black meetings and lynched known black leaders, destroying local political organizations.[37] Seeing the success of this deliberate "Mississippi Plan", South Carolina and other states followed it and also achieved white Democratic dominance. In 1877 by a national compromise, the last of federal troops were withdrawn from the region.

Even in this environment, black Mississippians continued to be elected to local office. However, black residents were deprived of all political power after white legislators passed a new state constitution in 1890 specifically to "eliminate the nigger from politics", according to the state's Democratic governor, James K. Vardaman.[38] It erected barriers to voter registration and instituted electoral provisions that effectively disenfranchised most black Mississippians and many poor whites. Estimates are that 100,000 black and 50,000 white men were removed from voter registration rolls in the state over the next few years.[39]

The loss of political influence contributed to the difficulties of African Americans in their attempts to obtain extended credit in the late 19th century. Together with imposition of Jim Crow and racial segregation laws, whites increased violence against blacks, with lynchings occurring through the period of the 1890s and extending to 1930.

20th century to present

[edit]

In 1900, blacks made up more than half of the state's population. By 1910, a majority of black farmers in the Delta had lost their land and became sharecroppers. By 1920, the third generation after freedom, most African Americans in Mississippi were landless laborers again facing poverty.[32] Starting about 1913, tens of thousands of black Americans left Mississippi for the North in the Great Migration to industrial cities such as St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Philadelphia and New York. They sought jobs, better education for their children, the right to vote, relative freedom from discrimination, and better living. In the migration of 1910–1940, they left a society that had been steadily closing off opportunity. Most migrants from Mississippi took trains directly north to Chicago and often settled near former neighbors.

Cotton crops failed due to boll weevil infestation and successive severe flooding in 1912 and 1913, creating crisis conditions for many African Americans. With control of the ballot box and more access to credit, white planters bought out such farmers, expanding their ownership of Delta bottomlands. They also took advantage of new railroads sponsored by the state.[32] Blacks also faced violence in the form of lynching, shooting, and the burning of churches. In 1923, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People stated "the Negro feels that life is not safe in Mississippi and his life may be taken with impunity at any time upon the slightest pretext or provocation by a white man".[40]

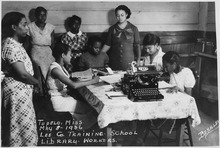

In the early 20th century, some industries were established in Mississippi, but jobs were generally restricted to whites, including child workers. The lack of jobs also drove some southern whites north to cities such as Chicago and Detroit, seeking employment, where they also competed with European immigrants. The state depended on agriculture, but mechanization put many farm laborers out of work.

By 1900, many white ministers, especially in the towns, subscribed to the Social Gospel movement, which attempted to apply Christian ethics to social and economic needs of the day. Many strongly supported Prohibition, believing it would help alleviate and prevent many sins.[41] Mississippi became a dry state in 1908 by an act of the state legislature.[42] It remained dry until the legislature passed a local option bill in 1966.[43]

African-American Baptist churches grew to include more than twice the number of members as their white Baptist counterparts. The African-American call for social equality resonated throughout the Great Depression in the 1930s and World War II in the 1940s.

The Second Great Migration from the South started in the 1940s, lasting until 1970. Almost half a million people left Mississippi in the second migration, three-quarters of them black. Nationwide during the first half of the 20th century, African Americans became rapidly urbanized and many worked in industrial jobs. The Second Great Migration included destinations in the West, especially California, where the buildup of the defense industry offered higher-paying jobs to both African Americans and whites.

Blacks and whites in Mississippi generated rich, quintessentially American music traditions: gospel music, country music, jazz, blues and rock and roll. All were invented, promulgated or heavily developed by Mississippi musicians, many of them African American, and most came from the Mississippi Delta. Many musicians carried their music north to Chicago, where they made it the heart of that city's jazz and blues.

So many African Americans left in the Great Migration that after the 1930s, they became a minority in Mississippi. In 1960 they made up 42% of the state's population.[44] The whites maintained their discriminatory voter registration processes established in 1890, preventing most blacks from voting, even if they were well educated. Court challenges were not successful until later in the century. After World War II, African-American veterans returned with renewed commitment to be treated as full citizens of the United States and increasingly organized to gain enforcement of their constitutional rights.

The Civil Rights movement had many roots in religion, and the strong community of churches helped supply volunteers and moral purpose for their activism. Mississippi was a center of activity, based in black churches, to educate and register black voters, and to work for integration. In 1954 the state had created the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a tax-supported agency, chaired by the Governor, that claimed to work for the state's image but effectively spied on activists and passed information to the local White Citizens' Councils to suppress black activism. White Citizens Councils had been formed in many cities and towns to resist integration of schools following the unanimous 1954 United States Supreme Court ruling (Brown v. Board of Education) that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. They used intimidation and economic blackmail against activists and suspected activists, including teachers and other professionals. Techniques included loss of jobs and eviction from rental housing.

In the summer of 1964 students and community organizers from across the country came to help register black voters in Mississippi and establish Freedom Schools. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was established to challenge the all-white Democratic Party of the Solid South. Most white politicians resisted such changes. Chapters of the Ku Klux Klan and its sympathizers used violence against activists, most notably the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 1964 during the Freedom Summer campaign. This was a catalyst for Congressional passage the following year of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Mississippi earned a reputation in the 1960s as a reactionary state.[45][46]

After decades of disenfranchisement, African Americans in the state gradually began to exercise their right to vote again for the first time since the 19th century, following the passage of federal civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965, which ended de jure segregation and enforced constitutional voting rights. Registration of African-American voters increased and black candidates ran in the 1967 elections for state and local offices. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party fielded some candidates. Teacher Robert G. Clark of Holmes County was the first African American to be elected to the State House since Reconstruction. He continued as the only African American in the state legislature until 1976 and was repeatedly elected into the 21st century, including three terms as Speaker of the House.[47]

In 1966, the state was the last to repeal officially statewide prohibition of alcohol. Before that, Mississippi had taxed the illegal alcohol brought in by bootleggers. Governor Paul Johnson urged repeal and the sheriff "raided the annual Junior League Mardi Gras ball at the Jackson Country Club, breaking open the liquor cabinet and carting off the Champagne before a startled crowd of nobility and high-ranking state officials".[48]

The end of legal segregation and Jim Crow led to the integration of some churches, but most today remain divided along racial and cultural lines, having developed different traditions. After the Civil War, most African Americans left white churches to establish their own independent congregations, particularly Baptist churches, establishing state associations and a national association by the end of the 20th century. They wanted to express their own traditions of worship and practice.[49] In more diverse communities, such as Hattiesburg, some churches have multiracial congregations.[50]

On August 17, 1969, Category 5 Hurricane Camille hit the Mississippi coast, killing 248 people and causing US$1.5 billion in damage (1969 dollars). Mississippi ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, in March 1984, which had already entered into force by August 1920; granting women the right to vote.[51]

In 1987, 20 years after the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in 1967's Loving v. Virginia that a similar Virginian law was unconstitutional, Mississippi repealed its ban on interracial marriage (also known as miscegenation), which had been enacted in 1890. It also repealed the segregationist-era poll tax in 1989. In 1995, the state symbolically ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which had abolished slavery in 1865. In 2009, the legislature passed a bill to repeal other discriminatory civil rights laws, which had been enacted in 1964, the same year as the federal Civil Rights Act, but ruled unconstitutional in 1967 by federal courts. Republican Governor Haley Barbour signed the bill into law.[52]

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, though a Category 3 storm upon final landfall, caused even greater destruction across the entire 90 miles (145 km) of the Mississippi Gulf Coast from Louisiana to Alabama.

The previous flag of Mississippi, used until June 30, 2020, featured the Confederate battle flag. Mississippi became the last state to remove the Confederate battle flag as an official state symbol on June 30, 2020, when Governor Tate Reeves signed a law officially retiring the second state flag. The current flag, The "New Magnolia" flag, was selected via referendum as part of the general election on November 3, 2020.[53][54] It officially became the state flag on January 11, 2021, after being signed into law by the state legislature and governor.

Geography

[edit]

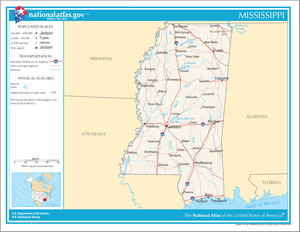

Mississippi is bordered to the north by Tennessee, to the east by Alabama, to the south by Louisiana and a narrow coast on the Gulf of Mexico; and to the west, across the Mississippi River, by Louisiana and Arkansas.

In addition to its namesake, major rivers in Mississippi include the Big Black River, the Pearl River, the Yazoo River, the Pascagoula River, and the Tombigbee River. Major lakes include Ross Barnett Reservoir, Arkabutla, Sardis, and Grenada, with the largest being Sardis Lake.

Mississippi is entirely composed of lowlands, the highest point being Woodall Mountain, at 807 ft (246 m) above sea level, in the northeastern part of the state. The lowest point is sea level at the Gulf Coast. The state's mean elevation is 300 ft (91 m) above sea level.

Most of Mississippi is part of the east Gulf Coastal Plain. The coastal plain is generally composed of low hills, such as the Pine Hills in the south and the North Central Hills. The Pontotoc Ridge and the Fall Line Hills in the northeast have somewhat higher elevations. Yellow-brown loess soil is found in the western parts of the state. The northeast is a region of fertile black earth uplands, a geology that extend into the Alabama Black Belt.

The coastline includes large bays at Bay St. Louis, Biloxi, and Pascagoula. It is separated from the Gulf of Mexico proper by the shallow Mississippi Sound, which is partially sheltered by Petit Bois Island, Horn Island, East and West Ship Islands, Deer Island, Round Island, and Cat Island.

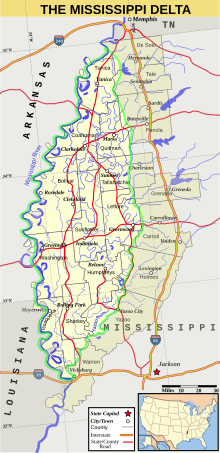

The northwest remainder of the state consists of the Mississippi Delta, a section of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. The plain is narrow in the south and widens north of Vicksburg. The region has rich soil, partly made up of silt which had been regularly deposited by the flood waters of the Mississippi River.

Areas under the management of the National Park Service include:[55]

- Brices Cross Roads National Battlefield Site near Baldwyn

- Gulf Islands National Seashore

- Natchez National Historical Park in Natchez

- Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail in Tupelo

- Natchez Trace Parkway

- Tupelo National Battlefield in Tupelo

- Vicksburg National Military Park and Cemetery in Vicksburg

Major cities and towns

[edit]

Mississippi City Population Rankings of at least 50,000 (United States Census Bureau as of 2017):[56]

Mississippi City Population Rankings of at least 20,000 but fewer than 50,000 (United States Census Bureau as of 2017):[56]

- Hattiesburg (46,377)

- Biloxi (45,908)

- Tupelo (38,114)

- Meridian (37,940)

- Olive Branch (37,435)

- Greenville (30,686)

- Horn Lake (27,095)

- Pearl (26,534)

- Madison (25,627)

- Starkville (25,352)

- Clinton (25,154)

- Ridgeland (24,266)

- Columbus (24,041)

- Brandon (23,999)

- Oxford (23,639)

- Vicksburg (22,489)

- Pascagoula (21,733)

Mississippi City Population Rankings of at least 10,000 but fewer than 20,000 (United States Census Bureau as of 2017):[56]

- Gautier (18,512)

- Laurel (18,493)

- Ocean Springs (17,682)

- Hernando (15,981)

- Clarksdale (15,732)

- Long Beach (15,642)

- Natchez (14,886)

- Corinth (14,643)

- Greenwood (13,996)

- Moss Point (13,398)

- McComb (13,267)

- Bay St. Louis (13,043)

- Canton (12,725)

- Grenada (12,267)

- Brookhaven (12,173)

- Cleveland (11,729)

- Byram (11,671)

- D'Iberville (11,610)

- Picayune (11,008)

- West Point (10,675)

- Yazoo City (11,018)

- Petal (10,633)

(See: Lists of cities, towns and villages, census-designated places, metropolitan areas, micropolitan areas, and counties in Mississippi)

Climate

[edit]

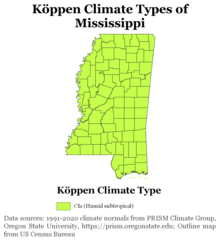

Mississippi has a humid subtropical climate with long, hot and humid summers, and short, mild winters. Temperatures average about 81 °F (27 °C) in July and about 42 °F (6 °C) in January. The temperature varies little statewide in the summer; however, in winter, the region near Mississippi Sound is significantly warmer than the inland portion of the state. The recorded temperature in Mississippi has ranged from −19 °F (−28 °C), in 1966, at Corinth in the northeast, to 115 °F (46 °C), in 1930, at Holly Springs in the north. Snowfall is scant throughout the state, occurring only rarely in the south. Yearly precipitation generally increases from north to south, with the regions closer to the Gulf being the most humid. Thus, Clarksdale, in the northwest, gets about 50 in (1,300 mm) of precipitation annually and Biloxi, in the south, about 61 in (1,500 mm). Small amounts of snow fall in northern and central Mississippi; snow is occasional in the southern part of the state.

The late summer and fall is the seasonal period of risk for hurricanes moving inland from the Gulf of Mexico, especially in the southern part of the state. Hurricane Camille in 1969 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which killed 238 people in the state, were the most devastating hurricanes to hit the state. Both caused nearly total storm surge destruction of structures in and around Gulfport, Biloxi, and Pascagoula.

As in the rest of the Deep South, thunderstorms are common in Mississippi, especially in the southern part of the state. On average, Mississippi has around 27 tornadoes annually; the northern part of the state has more tornadoes earlier in the year and the southern part a higher frequency later in the year. Two of the five deadliest tornadoes in United States history have occurred in the state. These storms struck Natchez, in southwest Mississippi (see The Great Natchez Tornado) and Tupelo, in the northeast corner of the state. About seven F5 tornadoes have been recorded in the state.

| Monthly normal high and low temperatures (°F) for various Mississippi cities | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gulfport | 61/43 | 64/46 | 70/52 | 77/59 | 84/66 | 89/72 | 91/74 | 91/74 | 87/70 | 79/60 | 70/51 | 63/45 |

| Jackson | 55/35 | 60/38 | 68/45 | 75/52 | 82/61 | 89/68 | 91/71 | 91/70 | 86/65 | 77/52 | 66/43 | 58/37 |

| Meridian | 58/35 | 63/38 | 70/44 | 77/50 | 84/60 | 90/67 | 93/70 | 93/70 | 88/64 | 78/51 | 68/43 | 60/37 |

| Tupelo | 50/30 | 56/34 | 65/41 | 74/48 | 81/58 | 88/66 | 91/70 | 91/68 | 85/62 | 75/49 | 63/40 | 54/33 |

| Source:[57] | ||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mississippi (1980–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.3 (12.4) |

58.7 (14.8) |

67.2 (19.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

82.6 (28.1) |

88.9 (31.6) |

91.4 (33.0) |

91.5 (33.1) |

86.3 (30.2) |

76.9 (24.9) |

66.5 (19.2) |

56.6 (13.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.3 (0.7) |

36.7 (2.6) |

43.8 (6.6) |

51.3 (10.7) |

60.3 (15.7) |

67.6 (19.8) |

70.6 (21.4) |

69.7 (20.9) |

63 (17) |

51.9 (11.1) |

43.1 (6.2) |

35.7 (2.1) |

52.3 (11.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.0 (130) |

5.2 (130) |

5.1 (130) |

5.0 (130) |

5.1 (130) |

4.4 (110) |

4.5 (110) |

3.9 (99) |

3.6 (91) |

4.1 (100) |

4.9 (120) |

5.7 (140) |

56.5 (1,420) |

| Source: USA.com[58] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

[edit]Climate change in Mississippi encompasses the effects of climate change, attributed to man-made increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, in the U.S. state of Mississippi.

Studies show that Mississippi is among a string of "Deep South" states that will experience the worst effects of climate change in the United States.[59] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports:

"In the coming decades, Mississippi will become warmer, and both floods and droughts may be more severe. Unlike most of the nation, Mississippi did not become warmer during the last 50 to 100 years. But soils have become drier, annual rainfall has increased, more rain arrives in heavy downpours, and sea level is rising about one inch every seven years. The changing climate is likely to increase damages from tropical storms, reduce crop yields, harm livestock, increase the number of unpleasantly hot days, and increase the risk of heat stroke and other heat-related illnesses".[60]Ecology, flora, and fauna

[edit]

Mississippi is heavily forested, with over half of the state's area covered by wild or cultivated trees. The southeastern part of the state is dominated by longleaf pine, in both uplands and lowland flatwoods and Sarracenia bogs. The Mississippi Alluvial Plain, or Delta, is primarily farmland and aquaculture ponds but also has sizeable tracts of cottonwood, willows, bald cypress, and oaks. A belt of loess extends north to south in the western part of the state, where the Mississippi Alluvial Plain reaches the first hills; this region is characterized by rich, mesic mixed hardwood forests, with some species disjunct from Appalachian forests.[61] Two bands of historical prairie, the Jackson Prairie and the Black Belt, run northwest to southeast in the middle and northeastern part of the state. Although these areas have been highly degraded by conversion to agriculture, a few areas remain, consisting of grassland with interspersed woodland of eastern redcedar, oaks, hickories, osage-orange, and sugarberry. The rest of the state, primarily north of Interstate 20 not including the prairie regions, consists of mixed pine-hardwood forest, common species being loblolly pine, oaks (e.g., water oak), hickories, sweetgum, and elm. Areas along large rivers are commonly inhabited by bald cypress, water tupelo, water elm, and bitter pecan. Commonly cultivated trees include loblolly pine, longleaf pine, cherrybark oak, and cottonwood.

There are approximately 3000 species of vascular plants known from Mississippi.[62] As of 2018, a project funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation aims to update that checklist of plants with museum (herbarium) vouchers and create an online atlas of each species's distribution.[63]

About 420 species of birds are known to inhabit Mississippi.

Mississippi has one of the richest fish faunas in the United States, with 204 native fish species.[64]

Mississippi also has a rich freshwater mussel fauna, with about 90 species in the primary family of native mussels (Unionidae).[65] Several of these species were extirpated during the construction of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway.

Mississippi is home to 63 crayfish species, including at least 17 endemic species.[66]

Mississippi is home to eight winter stonefly species.[67]

Ecological problems

[edit]Flooding

[edit]Due to seasonal flooding, possible from December to June, the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers and their tributaries created a fertile floodplain in the Mississippi Delta. The river's flooding created natural levees, which planters had built higher to try to prevent flooding of land cultivated for cotton crops. Temporary workers built levees along the Mississippi River on top of the natural levees that formed from dirt deposited after the river flooded.

From 1858 to 1861, the state took over levee building, accomplishing it through contractors and hired labor. In those years, planters considered their slaves too valuable to hire out for such dangerous work. Contractors hired gangs of Irish immigrant laborers to build levees and sometimes clear land. Many of the Irish were relatively recent immigrants from the famine years who were struggling to get established.[68] Before the American Civil War, the earthwork levees averaged six feet in height, although in some areas they reached twenty feet.

Flooding has been an integral part of Mississippi history, but clearing of the land for cultivation and to supply wood fuel for steamboats took away the absorption of trees and undergrowth. The banks of the river were denuded, becoming unstable and changing the character of the river. After the Civil War, major floods swept down the valley in 1865, 1867, 1874 and 1882. Such floods regularly overwhelmed levees damaged by Confederate and Union fighting during the war, as well as those constructed after the war.[69] In 1877, the state created the Mississippi Levee District for southern counties.

In 1879, the United States Congress created the Mississippi River Commission, whose responsibilities included aiding state levee boards in the construction of levees. Both white and black transient workers were hired to build the levees in the late 19th century. By 1882, levees averaged seven feet in height, but many in the southern Delta were severely tested by the flood that year.[69] After the 1882 flood, the levee system was expanded. In 1884, the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta Levee District was established to oversee levee construction and maintenance in the northern Delta counties; also included were some counties in Arkansas which were part of the Delta.[70]

Flooding overwhelmed northwestern Mississippi in 1912–1913, causing heavy damage to the levee districts. Regional losses and the Mississippi River Levee Association's lobbying for a flood control bill helped gain passage of national bills in 1917 and 1923 to provide federal matching funds for local levee districts, on a scale of 2:1. Although U.S. participation in World War I interrupted funding of levees, the second round of funding helped raise the average height of levees in the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta to 22 feet (6.7 m) in the 1920s.[71] Scientists now understand the levees have increased the severity of flooding by increasing the flow speed of the river and reducing the area of the floodplains. The region was severely damaged due to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which broke through the levees. There were losses of millions of dollars in property, stock and crops. The most damage occurred in the lower Delta, including Washington and Bolivar counties.[72]

Even as scientific knowledge about the Mississippi River has grown, upstream development and the consequences of the levees have caused more severe flooding in some years. Scientists now understand that the widespread clearing of land and building of the levees have changed the nature of the river. Such work removed the natural protection and absorption of wetlands and forest cover, strengthening the river's current. The state and federal governments have been struggling for the best approaches to restore some natural habitats in order to best interact with the original riverine ecology.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 7,600 | — | |

| 1810 | 31,306 | 311.9% | |

| 1820 | 75,448 | 141.0% | |

| 1830 | 136,621 | 81.1% | |

| 1840 | 375,651 | 175.0% | |

| 1850 | 606,526 | 61.5% | |

| 1860 | 791,305 | 30.5% | |

| 1870 | 827,922 | 4.6% | |

| 1880 | 1,131,597 | 36.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,289,600 | 14.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,551,270 | 20.3% | |

| 1910 | 1,797,114 | 15.8% | |

| 1920 | 1,790,618 | −0.4% | |

| 1930 | 2,009,821 | 12.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,183,796 | 8.7% | |

| 1950 | 2,178,914 | −0.2% | |

| 1960 | 2,178,141 | 0.0% | |

| 1970 | 2,216,912 | 1.8% | |

| 1980 | 2,520,638 | 13.7% | |

| 1990 | 2,573,216 | 2.1% | |

| 2000 | 2,844,658 | 10.5% | |

| 2010 | 2,967,297 | 4.3% | |

| 2020 | 2,961,279 | −0.2% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 2,943,045 | −0.6% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[73]

2024[74] | |||

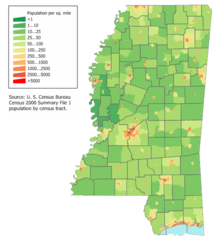

Mississippi's population has remained from 2 million people at the 1930 U.S. census, to 2.9 million at the 2020 census.[75] In contrast with Alabama to its east, and Louisiana to its west, Mississippi has been the slowest growing of the three Gulf coast states by population.[76] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Mississippi's center of population is located in Leake County, in the town of Lena.[77]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 1,196 homeless people in Mississippi.[78][79]

From 2000 to 2010, the United States Census Bureau reported that Mississippi had the highest rate of increase in people identifying as mixed-race, up 70 percent in the decade; it amounts to a total of 1.1 percent of the population.[50] In addition, Mississippi led the nation for most of the last decade in the growth of mixed marriages among its population. The total population has not increased significantly, but is young. Some of the above change in identification as mixed-race is due to new births. But, it appears mostly to reflect those residents who have chosen to identify as more than one race, who in earlier years may have identified by just one race or ethnicity. A binary racial system had been in place since slavery times and the days of official government racial segregation. In the civil rights era, people of African descent banded together in an inclusive community to achieve political power and gain restoration of their civil rights.

As the demographer William H. Frey noted, "In Mississippi, I think it's [identifying as mixed race] changed from within."[50] Historically in Mississippi, after Indian removal in the 1830s, the major groups were designated as black (African American), who were then mostly enslaved, and white (primarily European American). Matthew Snipp, also a demographer, commented on the increase in the 21st century in the number of people identifying as being of more than one race: "In a sense, they're rendering a more accurate portrait of their racial heritage that in the past would have been suppressed."[50]

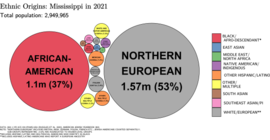

After having accounted for a majority of the state's population since well before the American Civil War and through the 1930s, today African Americans constitute approximately 37.8 percent of the state's population. Most have ancestors who were enslaved, with many forcibly transported from the Upper South in the 19th century to work on the area's new plantations. Many of these slaves were mixed race, with European ancestors, as there were many children born into slavery with white fathers. Some also have Native American ancestry.[80] During the first half of the 20th century, a total of nearly 400,000 African Americans left the state during the Great Migration, for opportunities in the North, Midwest and West. They became a minority in the state for the first time since early in its development.[81]

In 2018, The top countries of origin for Mississippi's immigrants were Mexico, Guatemala, India, the Philippines and Vietnam.[82]

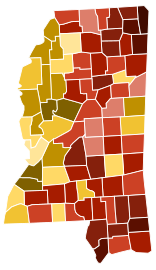

Race and ethnicity

[edit]

Non-Hispanic White 40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%90%+Black or African American40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%

| Race and ethnicity[75] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 55.4% | 57.9% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 36.4% | 37.6% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[b] | — | 3.6% | ||

| Asian | 1.1% | 1.5% | ||

| Native American | 0.5% | 1.6% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.04% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.2% | 0.7% | ||

| Racial composition | 1990[83] | 2000[84] | 2010[85] | 2020[86] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 63.5% | 61.4% | 59.1% | 56.0% |

| Black | 35.6% | 36.3% | 37.0% | 36.6% |

| Asian | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.1% |

| Native | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% |

| Other race | 0.1% | 0.5% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| Two or more races | – | 0.7% | 1.2% | 3.7% |

Americans of Scots-Irish, English and Scottish ancestry are present throughout the state. It is believed that there are more people with such ancestry than identify as such on the census, in part because their immigrant ancestors are more distant in their family histories. English, Scottish and Scots-Irish are generally the most under-reported ancestry groups in both the South Atlantic states and the East South Central states. The historian David Hackett Fischer estimated that a minimum 20% of Mississippi's population is of English ancestry, though the figure is probably much higher, and another large percentage is of Scottish ancestry. Many Mississippians of such ancestry identify simply as American on questionnaires, because their families have been in North America for centuries.[87][88] In the 1980 U.S. census, 656,371 Mississippians of a total of 1,946,775 identified as being of English ancestry, making them 38% of the state at the time.[89]

The state in 2010 had the highest proportion of African Americans in the nation. The African American percentage of population has begun to increase due mainly to a younger population than the whites (the total fertility rates of the two races are approximately equal). Due to patterns of settlement and whites putting their children in private schools, in almost all of Mississippi's public school districts, a majority of students are African American. African Americans are the majority ethnic group in the northwestern Yazoo Delta, and the southwestern and the central parts of the state. These are areas where, historically, African Americans owned land as farmers in the 19th century following the Civil War, or worked on cotton plantations and farms.[90]

People of French Creole ancestry form the largest demographic group in Hancock County on the Gulf Coast. The African American, Choctaw (mostly in Neshoba County), and Chinese American portions of the population are also almost entirely native born.

The Chinese first came to Mississippi as contract workers from Cuba and California in the 1870s, and they originally worked as laborers on the cotton plantations. However, most Chinese families came later between 1910 and 1930 from other states, and most operated small family-owned groceries stores in the many small towns of the Delta.[91] In these roles, the ethnic Chinese carved out a niche in the state between black and white, where they were concentrated in the Delta. These small towns have declined since the late 20th century, and many ethnic Chinese have joined the exodus to larger cities, including Jackson. Their population in the state overall has increased in the 21st century.[92][93][94][95]

In the early 1980s many Vietnamese immigrated to Mississippi and other states along the Gulf of Mexico, where they became employed in fishing-related work.[96]

Italians were one of the largest immigrant groups in the state during the first three decades of the twentieth century.[97]

Mexicans have been in the state since the early 20th century.[98]

There is also a German community in the state.[99]

As of 2011, 53.8% of Mississippi's population younger than age 1 were minorities, meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white.[100]

Birth data

[edit]

Note: Births in table do not add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[101] | 2014[102] | 2015[103] | 2016[104] | 2017[105] | 2018[106] | 2019[107] | 2020[108] | 2021[109] | 2022[110] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 20,818 (53.9%) | 20,894 (53.9%) | 20,730 (54.0%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 19,730 (51.0%) | 19,839 (51.3%) | 19,635 (51.1%) | 19,411 (51.2%) | 18,620 (49.8%) | 18,597 (50.2%) | 18,229 (49.8%) | 17,648 (49.8%) | 17,818 (50.7%) | 17,703 (51.1%) |

| Black | 17,020 (44.0%) | 17,036 (44.0%) | 16,846 (43.9%) | 15,879 (41.9%) | 16,087 (43.1%) | 15,797 (42.7%) | 15,706 (42.9%) | 15,155 (42.7%) | 14,619 (41.6%) | 14,035 (40.5%) |

| Asian | 504 (1.3%) | 583 (1.5%) | 559 (1.5%) | 475 (1.3%) | 502 (1.3%) | 411 (1.1%) | 455 (1.2%) | 451 (1.3%) | 404 (1.1%) | 396 (1.1%) |

| American Indian | 292 (0.7%) | 223 (0.6%) | 259 (0.7%) | 215 (0.6%) | 225 (0.6%) | 238 (0.6%) | 242 (0.7%) | 252 (0.7%) | 227 (0.6%) | 246 (0.7%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 1,496 (3.9%) | 1,547 (4.0%) | 1,613 (4.2%) | 1,664 (4.4%) | 1,650 (4.4%) | 1,666 (4.5%) | 1,709 (4.7%) | 1,679 (4.7%) | 1,756 (5.0%) | 1,930 (5.6%) |

| Total Mississippi | 38,634 (100%) | 38,736 (100%) | 38,394 (100%) | 37,928 (100%) | 37,357 (100%) | 37,000 (100%) | 36,636 (100%) | 35,473 (100%) | 35,156 (100%) | 34,675 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

In 2022, Mississippi had the highest teen birth rate of any state, at 26.4 births per 1,000 females ages 15 to 19 years of age.[111]

LGBT community

[edit]The 2010 United States census counted 6,286 same-sex unmarried-partner households in Mississippi, an increase of 1,512 since the 2000 United States census.[112] Of those same-sex couples roughly 33% contained at least one child, giving Mississippi the distinction of leading the nation in the percentage of same-sex couples raising children.[113] Mississippi has the largest percentage of African American same-sex couples among total households. The state capital, Jackson, ranks tenth in the nation in concentration of African American same-sex couples. The state ranks fifth in the nation in the percentage of Hispanic same-sex couples among all Hispanic households and ninth in the highest concentration of same-sex couples who are seniors.[114]

Language

[edit]| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[115] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 1.9% |

| French | 0.4% |

| German, Vietnamese, and Choctaw (tied) | 0.2% |

| Korean, Chinese, Tagalog, Italian (tied) | 0.1% |

In 2000, 96.4% of Mississippi residents five years old and older spoke only English in the home, a decrease from 97.2% in 1990.[116] English is largely Southern American English, with some South Midland speech in northern and eastern Mississippi. There is a common absence of final /r/, particularly in the elderly natives and African Americans, and the lengthening and weakening of the diphthongs /aɪ/ and /ɔɪ/ as in 'ride' and 'oil'. South Midland terms in northern Mississippi include: tow sack (burlap bag), dog irons (andirons), plum peach (clingstone peach), snake doctor (dragonfly), and stone wall (rock fence).[116]

Religion

[edit]Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[117]

Under French and Spanish rule beginning in the 17th century, European colonists were mostly Roman Catholics. The growth of the cotton culture after 1815 brought in tens of thousands of Anglo-American settlers each year, most of whom were Protestants from Southeastern states. Due to such migration, there was rapid growth in the number of Protestant denominations and churches, especially among the Methodists, Presbyterians and Baptists.[118]

The revivals of the Great Awakening in the late 18th and early 19th centuries initially attracted the "plain folk" by reaching out to all members of society, including women and blacks. Both slaves and free blacks were welcomed into Methodist and Baptist churches. Independent black Baptist churches were established before 1800 in Virginia, Kentucky, South Carolina and Georgia, and later developed in Mississippi as well.

In the post-Civil War years, religion became more influential as the South became known as the "Bible Belt". By 2014, the Pew Research Center determined 83% of its population was Christian.[119] In a separate study by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2020, 80% of the population was Christian.[120] In another Public Religion study in 2022, 84% of the population was Christian spread throughout Protestants (74%), Catholics (8%), Jehovah's Witnesses (1%), and Mormons (1%).

Since the 1970s, fundamentalist conservative churches have grown rapidly, fueling Mississippi's conservative political trends among whites.[118] In 1973 the Presbyterian Church in America attracted numerous conservative congregations. As of 2010, Mississippi remained a stronghold of the denomination, which originally was brought by Scots immigrants. The state has the highest adherence rate of the PCA in 2010, with 121 congregations and 18,500 members. It is among the few states where the PCA has higher membership than the PC(USA).[121]

According to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), in 2010 the Southern Baptist Convention had 907,384 adherents and was the largest religious denomination in the state, followed by the United Methodist Church with 204,165, and the Roman Catholic Church with 112,488.[122] Other religions have a small presence in Mississippi; as of 2010, there were 5,012 Muslims; 4,389 Hindus; and 816 of the Baháʼí Faith.[122]

According to the Pew Research Center in 2014, with evangelical Protestantism as the predominant Christian affiliation, the Southern Baptist Convention remained the largest denomination in the state.[119] Non-denominational Evangelicals were the second-largest, followed by historically African American denominations such as the National Baptist Convention, USA and Progressive National Baptist Convention.

Public opinion polls have consistently ranked Mississippi as the most religious state in the United States, with 59% of Mississippians considering themselves "very religious". The same survey also found that 11% of the population were non-Religious.[123] In a 2009 Gallup poll, 63% of Mississippians said that they attended church weekly or almost weekly—the highest percentage of all states (U.S. average was 42%, and the lowest percentage was in Vermont at 23%).[124] Another 2008 Gallup poll found that 85% of Mississippians considered religion an important part of their daily lives, the highest figure among all states (U.S. average 65%).[125]

Health

[edit]The state is ranked 50th or last place among all the states for health care, according to the Commonwealth Fund, a nonprofit foundation working to advance performance of the health care system.[126]

Mississippi has the highest rate of infant and neonatal deaths of any U.S. state. Age-adjusted data also shows Mississippi has the highest overall death rate, and the highest death rate from heart disease, hypertension and hypertensive renal disease, influenza and pneumonia.[127]

In 2011, Mississippi (and Arkansas) had the fewest dentists per capita in the United States.[128]

For three years in a row, more than 30 percent of Mississippi's residents have been classified as obese. In a 2006 study, 22.8 percent of the state's children were classified as such. Mississippi had the highest rate of obesity of any U.S. state from 2005 to 2008, and also ranks first in the nation for high blood pressure, diabetes, and adult inactivity.[129][130] In a 2008 study of African-American women, contributing risk factors were shown to be: lack of knowledge about body mass index (BMI), dietary behavior, physical inactivity and lack of social support, defined as motivation and encouragement by friends.[131] A 2002 report on African-American adolescents noted a 1999 survey which suggests that a third of children were obese, with higher ratios for those in the Delta.[132]

The study stressed that "obesity starts in early childhood extending into the adolescent years and then possibly into adulthood". It noted impediments to needed behavioral modification, including the Delta likely being "the most underserved region in the state" with African Americans the major ethnic group; lack of accessibility and availability of medical care; and an estimated 60% of residents living below the poverty level. Additional risk factors were that most schools had no physical education curriculum and nutrition education is not emphasized. Previous intervention strategies may have been largely ineffective due to not being culturally sensitive or practical.[132] A 2006 survey found nearly 95 percent of Mississippi adults considered childhood obesity to be a serious problem.[133]

A 2017 study found that Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Mississippi was the leading health insurer with 53% followed by UnitedHealth Group at 13%.[134]

Economy

[edit]

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that Mississippi's total state product in 2024 was $150 billion.[135] GDP growth was .5 percent in 2015 and is estimated to be 2.4 in 2016 according to Darrin Webb, the state's chief economist, who noted it would make two consecutive years of positive growth since the recession.[136] Per capita personal income in 2006 was $26,908, the lowest per capita personal income of any state, but the state also has the nation's lowest living costs. 2015 data records the adjusted per capita personal income at $40,105.[136] Mississippians consistently rank as one of the highest per capita in charitable contributions.[137]

At 56 percent, the state has one of the lowest workforce participation rates in the country. Approximately 70,000 adults are disabled, which is 10 percent of the workforce.[136]

Mississippi's rank as one of the poorest states is related to its dependence on cotton agriculture before and after the Civil War, late development of its frontier bottomlands in the Mississippi Delta, repeated natural disasters of flooding in the late 19th and early 20th century that required massive capital investment in levees, and ditching and draining the bottomlands, and slow development of railroads to link bottomland towns and river cities.[138] In addition, when Democrats regained control of the state legislature, they passed the 1890 constitution that discouraged corporate industrial development in favor of rural agriculture, a legacy that would slow the state's progress for years.[139]

Before the Civil War, Mississippi was the fifth-wealthiest state in the nation, its wealth generated by the labor of slaves in cotton plantations along the rivers.[140] Slaves were counted as property and the rise in the cotton markets since the 1840s had increased their value. By 1860, a majority—55 percent—of the population of Mississippi was enslaved.[141] Ninety percent of the Delta bottomlands were undeveloped and the state had low overall density of population.

Largely due to the domination of the plantation economy, focused on the production of agricultural cotton, the state's elite was reluctant to invest in infrastructure such as roads and railroads. They educated their children privately. Industrialization did not reach many areas until the late 20th century. The planter aristocracy, the elite of antebellum Mississippi, kept the tax structure low for their own benefit, making only private improvements. Before the war the most successful planters, such as Confederate President Jefferson Davis, owned riverside properties along the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers in the Mississippi Delta. Away from the riverfronts, most of the Delta was undeveloped frontier.

During the Civil War, 30,000 Mississippi soldiers, mostly white, died from wounds and disease, and many more were left crippled and wounded. Changes to the labor structure and an agricultural depression throughout the South caused severe losses in wealth. In 1860 assessed valuation of property in Mississippi had been more than $500 million, of which $218 million (43 percent) was estimated as the value of slaves. By 1870, total assets had decreased in value to roughly $177 million.[142]

Poor whites and landless former slaves suffered the most from the postwar economic depression. The constitutional convention of early 1868 appointed a committee to recommend what was needed for relief of the state and its citizens. The committee found severe destitution among the laboring classes.[143] It took years for the state to rebuild levees damaged in battles. The upset of the commodity system impoverished the state after the war. By 1868 an increased cotton crop began to show possibilities for free labor in the state, but the crop of 565,000 bales produced in 1870 was still less than half of prewar figures.[144]

Blacks cleared land, selling timber and developing bottomland to achieve ownership. In 1900, two-thirds of farm owners in Mississippi were blacks, a major achievement for them and their families. Due to the poor economy, low cotton prices and difficulty of getting credit, many of these farmers could not make it through the extended financial difficulties. Two decades later, the majority of African Americans were sharecroppers. The low prices of cotton into the 1890s meant that more than a generation of African Americans lost the result of their labor when they had to sell their farms to pay off accumulated debts.[32]

After the Civil War, the state refused for years to build human capital by fully educating all its citizens. In addition, the reliance on agriculture grew increasingly costly as the state suffered loss of cotton crops due to the devastation of the boll weevil in the early 20th century, devastating floods in 1912–1913 and 1927, collapse of cotton prices after 1920, and drought in 1930.[138]

It was not until 1884, after the flood of 1882, that the state created the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta District Levee Board and started successfully achieving longer-term plans for levees in the upper Delta.[70] Despite the state's building and reinforcing levees for years, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 broke through and caused massive flooding of 27,000 square miles (70,000 km2) throughout the Delta, homelessness for hundreds of thousands, and millions of dollars in property damages. With the Depression coming so soon after the flood, the state suffered badly during those years. In the Great Migration, hundreds of thousands of African Americans migrated North and West for jobs and chances to live as full citizens.

Energy

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2023) |

Solar power

[edit]

Mississippi has substantial potential for solar power, though it remains an underutilized generation method. The rate of installations has increased in recent years, reaching 438 MW of installed capacity in early 2023, ranking 36th among the states.[145] Rooftop photovoltaics could provide 31.2% of all electricity used in Mississippi from 11,700 MW if solar panels were installed on every available roof.[146]

In 2011, the Sierra Club sued the United States Department of Energy which was providing investment in a coal gasification plant being built by Mississippi Power.[147] In 2012 Mississippi Power had only 0.05% renewables in its power mix. In a settlement in 2014, Mississippi Power agreed to allow net metering, and to offer 100 MW of wind or solar power purchase agreements. Mississippi is one of only two states, along with Florida, to have no potential for standard commercial wind power, having no locations that would provide at least 30% capacity factor, although 30,000 MW of 100 meter high turbines would operate at 25% capacity factor.[148]

Mississippi Power which provides energy in southeast Mississippi has started a program to contract for 210 MW of solar power in 2014, possibly increasing to 525 MW. 100 MW would be from small scale distributed installations.[149]

Offering net metering is required by federal law, but Mississippi is one of only four states to not have adopted a statewide policy on net metering, which means it needs to be negotiated with the utility.[150][151]Entertainment and tourism

[edit]The legislature's 1990 decision to legalize casino gambling along the Mississippi River and the Gulf Coast has led to increased revenues and economic gains for the state. Gambling towns in Mississippi have attracted increased tourism: they include the Gulf Coast resort towns of Bay St. Louis, Gulfport and Biloxi, and the Mississippi River towns of Tunica (the third largest gaming area in the United States), Greenville, Vicksburg and Natchez.

Before Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast, Mississippi was the second-largest gambling state in the Union, after Nevada and ahead of New Jersey.[citation needed] In August 2005, an estimated $500,000 per day in tax revenue, equivalent to $780,031 in 2023, was lost following Hurricane Katrina's severe damage to several coastal casinos in Biloxi.[152] Because of the destruction from this hurricane, on October 17, 2005, Governor Haley Barbour signed a bill into law that allows casinos in Hancock and Harrison counties to rebuild on land (but within 800 feet (240 m) of the water). The only exception is in Harrison County, where the new law states that casinos can be built to the southern boundary of U.S. Route 90.[citation needed]

In 2012, Mississippi had the sixth largest gambling revenue of any state, at $2.25 billion.[153] The federally recognized Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians has established a gaming casino on its reservation, which yields revenue to support education and economic development.[citation needed] While regulated sports betting has been active since 2018, the lack of mobile sports betting laws has limited the tax revenue paid by sportsbooks to the state.[154] From 2018 to September 2024, Mississippi sports betting was repsonsible for $37 million in tax benefits.

Momentum Mississippi, a statewide, public–private partnership dedicated to the development of economic and employment opportunities in Mississippi, was adopted in 2005.[155]

Manufacturing

[edit]

Mississippi, like the rest of its southern neighbors, is a right-to-work state. It has some major automotive factories, such as the Toyota Mississippi Plant in Blue Springs and a Nissan Automotive plant in Canton. The latter produces the Nissan Titan.

GreenTech Automotive received $6 million of incentive financing from the state of Mississippi and Tunica County to build an automotive plant in the county.[156][157] The facility was shut down in January 2017.[158] GreenTech had promised to invest $60 million in the manufacturing plant, but it produced few cars if any.[156] A Mississippi state auditor's review begun in 2016 found documentation reflecting only $3 million spent by GreenTech on automotive assembly equipment and parts.[156] While the company had promised to create 350 full-time jobs, it was found to never have created more than 94 active, full-time jobs in Mississippi at any time.[156][159]

In July 2017, the Mississippi state auditor demanded that GreenTech and its CEO Charlie Wang pay Mississippi $6 million because Greentech had not lived up to its promises.[159][160] The auditor said: "I would venture that there isn’t really much of an operation in Tunica at all. This appears to have been a game of smoke and mirrors, and a corporate entity that never had any intention to deliver on the promises it made."[160] In November 2017, Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood sued the company.[159] GreenTech declared bankruptcy in February 2018.[161][162] In a 2020 final settlement, it paid Mississippi and Tunica County only $575,000.[156]

Taxation

[edit]As of August 2024[update], Mississippi collects personal income tax at a flat rate of 5% for all income over $10,000.[163] The retail sales tax rate in Mississippi is 7%.[164] This rate is applied also to groceries, making it the highest grocery tax in the United States.[165] Tupelo levies a local sales tax of 2.5%.[166] State sales tax growth was 1.4 percent in 2016 and estimated to be slightly less in 2017.[136] For purposes of assessment for ad valorem taxes, taxable property is divided into five classes.[167]

On August 30, 2007, a report by the United States Census Bureau indicated that Mississippi was the poorest state in the country. Major cotton farmers in the Delta have large, mechanized plantations, and they receive the majority of extensive federal subsidies going to the state, yet many other residents still live as poor, rural, landless laborers. The state's sizable poultry industry has faced similar challenges in its transition from family-run farms to large mechanized operations.[168] Of $1.2 billion from 2002 to 2005 in federal subsidies to farmers in the Bolivar County area of the Delta, only 5% went to small farmers. There has been little money apportioned for rural development. Small towns are struggling. More than 100,000 people have left the region in search of work elsewhere.[169] The state had a median household income of $34,473.[170]

Employment

[edit]As of February 2023, the state's unemployment rate was 3.7%, the eleventh-highest in the country, tied with Arizona, Massachusetts, and West Virginia.[171] This is an improvement over the 3.9% rate in January 2023, and 4% over the previous year. The highest unemployment rate recorded in the state was in April 2020, during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, at 15.6%.[172]

Federal subsidies and spending

[edit]Mississippi ranks as having the second-highest ratio of spending to tax receipts of any state. In 2005, Mississippi citizens received approximately $2.02 per dollar of taxes in the way of federal spending. This ranks the state second-highest nationally, and represents an increase from 1995, when Mississippi received $1.54 per dollar of taxes in federal spending and was 3rd highest nationally.[173] This figure is based on federal spending after large portions of the state were devastated by Hurricane Katrina, requiring large amounts of federal aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). However, from 1981 to 2005, it was at least number four in the nation for federal spending vs. taxes received.[174]

A proportion of federal spending in Mississippi is directed toward large federal installations such as Camp Shelby, John C. Stennis Space Center, Meridian Naval Air Station, Columbus Air Force Base, and Keesler Air Force Base. Three of these installations are located in the area affected by Hurricane Katrina.

Politics and government

[edit]

As with all other U.S. states and the federal government, Mississippi's government is based on the separation of legislative, executive and judicial power. Executive authority in the state rests with the Governor, currently Tate Reeves (R). The lieutenant governor, currently Delbert Hosemann (R), is elected on a separate ballot. Both the governor and lieutenant governor are elected to four-year terms of office. Unlike the federal government, but like many other U.S. states, most of the heads of major executive departments are elected by the citizens of Mississippi rather than appointed by the governor.